Leyla Uysal: Weaving Culture, Ecology, and Design at the GSD

When Leyla Uysal (MDes ’24, MLA ’27) arrived at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), she was already navigating an extraordinary path. An urban planner, entrepreneur, and mother, she had long worked to uplift Kurdish communities in her native Türkiye. Yet it was at Harvard that her journey deepened—becoming, as she puts it, “a dialogue with nature, design, and the world itself.” Through the Master of Design (MDes) and now the Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) programs, Uysal has found the GSD to be a catalyst for reimagining how creativity, culture, and ecology can intertwine to shape more compassionate and sustainable futures.

“Since my childhood, I’ve lived in close conversation with nature,” Uysal says, reflecting on her Indigenous Mesopotamian upbringing in a war-scarred area of rural Türkiye. Her Kurdish community—long oppressed by mainstream society—remained largely untouched by modernization, preserving a way of life rooted in intimacy with the land. What might have been deprivation became, in hindsight, a kind of inheritance. “Not being introduced to modernization, globalization, and industrialization has a positive impact on our bond with nature,” she explains. “We see everything as valuable and precious, and we live with much less waste. This is the blessing of not being fully modernized.”

This blessing, however, came at a cost. Education was not a birthright in Uysal’s community; it was something to be won. As a girl, she had to persuade her parents to allow her to attend school, defying customs that deemed education improper for daughters. “This was the curse of not living in a modernized setting,” she recalls. “My going to school was seen as dishonoring my culture.” Within her tribe of nearly six thousand people, Uysal became the first woman to graduate from high school—and the first person ever to attend college. Today, she notes with pride, many of her younger female relatives have followed in her path.

In time, Uysal left her family homestead for Istanbul, where she enrolled at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University. There she earned a bachelor’s degree in urban and regional planning while also studying ecology and ecosystem restoration—a synthesis that would become central to her later work. In 2012, she moved to Boston with two goals: to learn English and, inspired by Charles Waldheim’s theories of landscape urbanism, to explore opportunities for study at the GSD. Marriage and motherhood followed, and for a few years her energy turned inward, toward family and the fragile equilibrium of building a new life abroad. But the memory of her own struggles lingered. “I wanted to help others who were facing the same challenges I did,” she says.

Photo: Brian McWilliams.

That impulse gave rise to Bajer Watches , a social enterprise founded, in her words, “to empower women and children, to provide them opportunities to have a better life.” Through Bajer, which produces high-end timepieces, Uysal partners with two Turkish NGOs that create educational and employment opportunities for rural Kurdish women and children. Each watch, crafted by hand, carries a piece of that story: the leather bands are inscribed with motifs drawn from Kurdish rugs—ancient symbols of clarity, resistance, and protection once woven by women as a means of communication when traditions required their silence. “The brand brings that story to the front line,” Uysal says. “Through design and craft, we tell the world that we exist.”

Bajer soon drew attention from the press , its blend of activism and aesthetics striking a resonant chord. Yet even as her company grew, Uysal felt another calling stirring. The planner in her—the thinker who saw systems, cities, and landscapes as interconnected—was restless. “I thought, I need to go back to school,” she recalls, “and use my skills for the next generations.”

In 2022, Uysal returned to academia, enrolling in the MDes program at the Harvard GSD. It marked, as she puts it, “a beautiful new chapter in my life.” She had always felt close to nature, but the MDes program gave that intuition an intellectual framework. As a student in the Ecologies domain, she immersed herself in the science of climate systems, exploring how data, policy, and design intersect. “I took many science, data, policy, and technology classes in the context of climate change,” she says. “My perspective became more grounded, and now everything I do is rooted in it.”

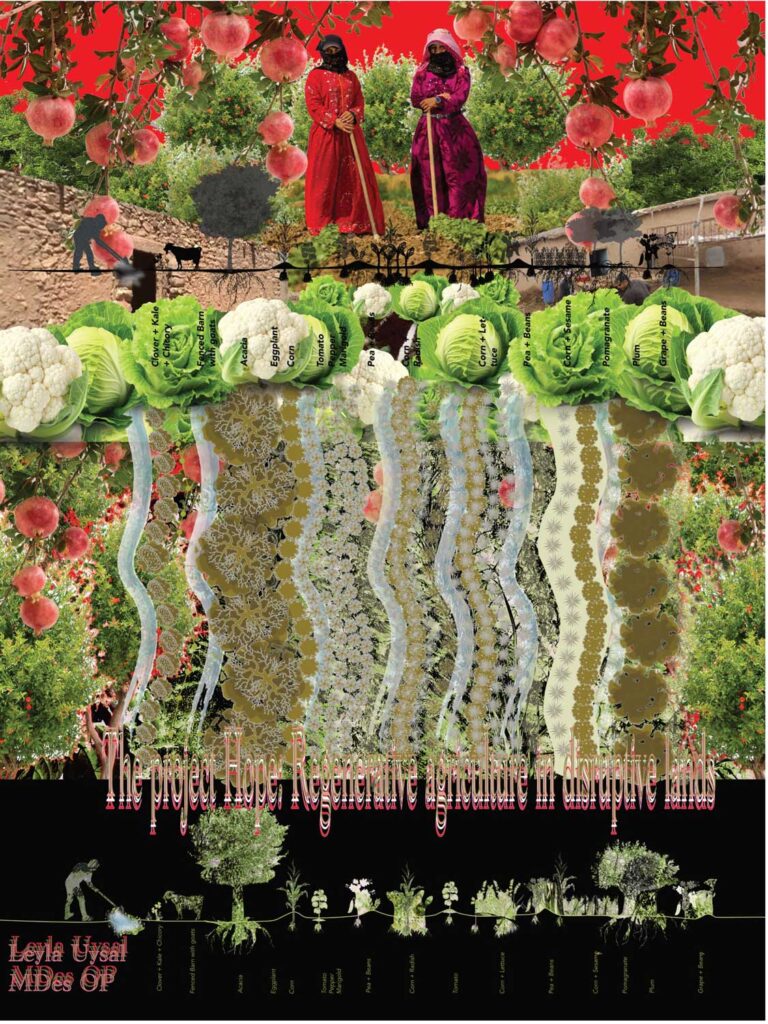

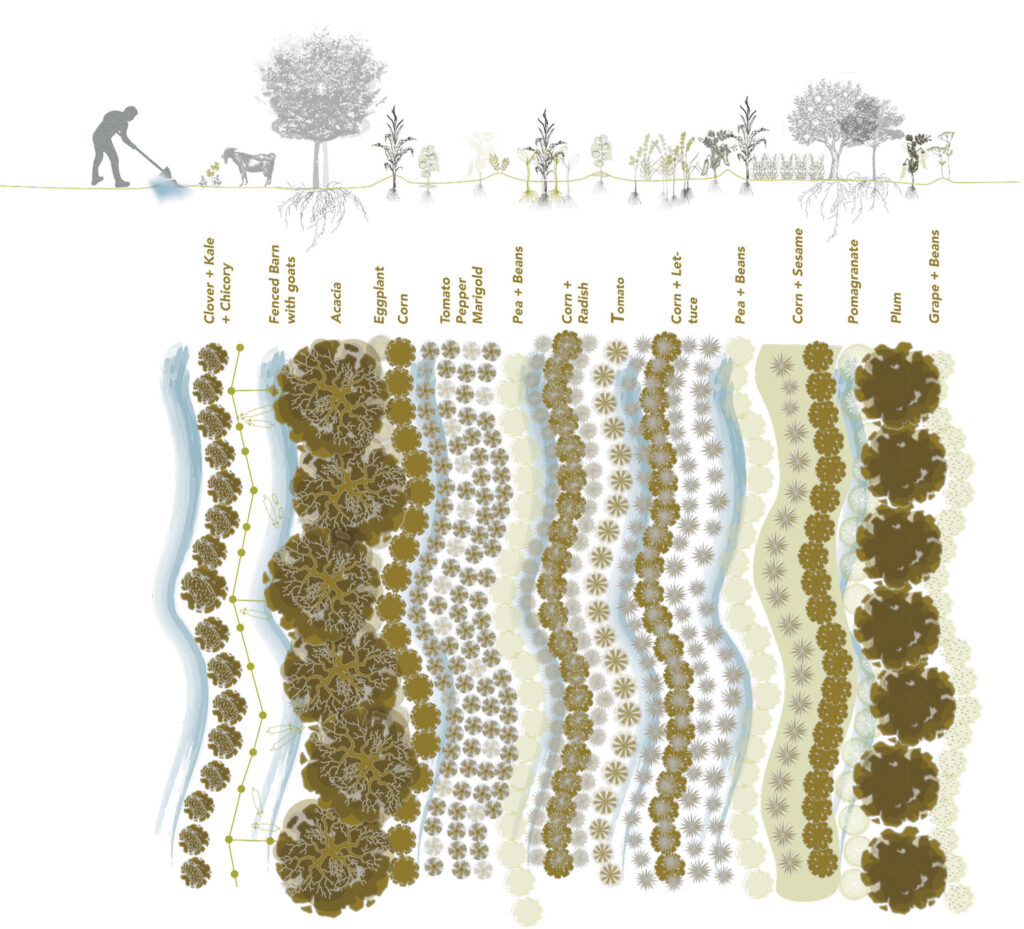

Her studies coalesced in “Project of Hope: Re-Imagining Indigenous Lands; Recovering through Memory,” supported by the Penny White Project Fund. “Project Hope” addresses the landmines scattered along Türkiye’s Syrian, Iraqi, and Iranian borders—about two million buried among ancient olive and pistachio fields—that have scarred both the land and its people. Rooted in a desire to restore memory and livelihood, the project uses landscape and permaculture design as tools to help Kurds reconnect with their sustainable farming traditions and reclaim their way of life. The work blended design, ecology, and cultural memory, proposing ways Indigenous landscapes might be repossessed—not only physically, but emotionally and symbolically.

After completing the MDes in 2024, Uysal’s curiosity only deepened. That summer, she began a PhD in environmental planning and policy program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), under the guidance of professors Janelle Knox-Hayes and Lawrence Susskind . Her research, ambitious in scope, examines the role of human ego in design and planning, exploring how humility and reciprocity might reshape zoning, development, and our relationship to land. “It’s about rethinking how we plan on this planet,” she says—a question that links the human scale of design to the vastness of the Earth itself.

The complexity of that inquiry soon drew her back to landscape itself. In the fall of 2025, Uysal enrolled in the MLA program at the GSD, supported by a full scholarship from the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture. She describes the MLA as a foundation for her doctoral research—a way to integrate lived experience with ecological design. “It allows me to build a more inclusive, Earth-oriented, future-oriented approach,” she says, “to inspire planners, architects, and designers to rethink their work.”

This year, she added yet another layer to her work: teaching. At MIT, she is a teaching assistant for a course on quantitative and qualitative research methodologies—a role she approaches not as an authority, but as a participant in an ongoing exchange. “I’m still learning,” she says. “I’m learning from my students already.”

In some ways, Uysal’s work has always been a return—a long arc from southeastern Türkiye to the classrooms of Cambridge, from handmade rugs to digital mapping, from silence to speech. What began as a fight for an education has evolved into a philosophy of design that treats the planet as a living archive of memory and meaning. It is a perspective shaped as much by experience as by scholarship: the child who watched the seasons shift over an ancient landscape has become the scholar urging designers and planners to move with, not against, the rhythms of our planet.

Uysal’s story is less about success than about continuity—the enduring thread between land and learning, between the resilience of her Kurdish ancestors and the generative curiosity that defines her work today. “Every step,” she says, “is another way of listening—to people, to place, and to the Earth itself.”

Practicing Growth in a Finite World: An Ethics Of Patience and Pragmatism

Two themes—pragmatism and time—dominated last week’s Practicing Growth in a Finite World, a Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) panel presented as this year’s Carl E. Sapers Ethics in Practice Lecture and hosted by the GSD Practice Forum. Four experts—one philosopher and three built‑environment practitioners—approached the question of growth and sustainability in a resource‑constrained world from distinct vantage points. Their conversation, urgent yet mindful of the incremental pace of change, surfaced ethical frameworks for 21st‑century practice and examined how designers can work within today’s constraints to make room for future transformation.

Architects, planners, and designers face a constellation of ethical quandaries. Moderator Elizabeth Bowie Christoforetti, assistant professor in practice of architecture and chair of the GSD Practice Forum, set the stage with a sobering fact: buildings produce more than 40 percent of global carbon emissions. In an age of relentless urban growth, that number captures a central paradox. Political and professional pressures demand speed—the rapid delivery of affordable housing and public infrastructure—even as every new square foot adds to the planet’s carbon and waste loads. Technology can scale these efforts , magnifying both progress and harm—harm potentially so devastating that some commentators argue for a moratorium on new construction. Beneath it all runs a familiar tension: the push to maximize returns for clients versus the desire to create culturally meaningful work. As Christoforetti observed, “the context for 21st-century design is thus a pressure cooker of external complexities.”

The urgency of the moment was brought into focus by philosopher Mathias Risse —Berthold Beitz Professor in Human Rights, Global Affairs, and Philosophy and director of the Carr-Ryan Center for Human Rights at the Harvard Kennedy School. “Architecture and design are at an ethical crossroads,” he argued. The only ethically responsible path forward, Risse suggested, is to become a “pragmatic moral agent”—someone who “works within existing systems to minimize environmental impact, promote sustainable practices, and gradually shift attitudes toward building and consumption.” The practical and temporal dimensions he outlined echoed through the reflections of the remaining three panelists.

Jane Amidon (MLA ’95), professor of landscape architecture and director of the Urban Landscape Program at Northeastern University, examined how practitioners navigate questions of public space, nature, and human experience. She pointed to large-scale, dynamic projects, such as those involving ecological rehabilitation and landscape maturation, that rely on “small tools of incremental change” and sustained advocacy—efforts that unfold over decades. Working closely with communities, she noted, designers can help shift expectations and foster acceptance of new approaches, such as coastal landscape projects in recent years that make room for rising water rather than trying, futilely, to hold it back.

“I’m interested in how design can work within the systems of today and catalyze or allow for the possibility of a different tomorrow,” said Neeraj Bhatia, advocating a similar forward-looking approach. A professor at the California College of the Arts and founder of THE OPEN WORKSHOP , a design-research practice, Bhatia discussed Lots Will Tear Us Apart, a recent collaboration with Spiegel Aihara Workshop that proposes a new housing typology for San Francisco. The project reimagines community living by rejecting conventional property division and private ownership, instead using prefabricated cores and flexible configurations to promote alternative living arrangements that allow for higher density and communal land. “The project asks how the architect can preconfigure the conditions for more collectivity, sharing, and social resilience,” Bhatia explained. “It offers the possibility of other ways of life that can slowly reconfigure the system over time.”

Dr. Dana Cuff , a professor at UCLA, concluded the discussion by focusing on spatial justice and the work she leads through cityLAB , a UCLA-based non-profit research and design center. “In every form of practice,” Cuff observed, “there are ways of doing work that step outside a capitalist model, whether it’s pro bono efforts in a traditional practice or … an organization dedicated to something like affordable housing.” One of cityLAB’s first breakthroughs was its research into the feasibility of accessory dwelling units (ADUs) in California, which helped shape 2016 legislation that opened the door for an estimated 8.1 million ADUs statewide. Building on that momentum, Cuff and her team turned their attention to small vacant lots throughout Los Angeles, launching Small Lots, Big Impact in spring 2025—a design competition aimed at prototyping and promoting housing on underused parcels. As she remarked in response to an audience question, “Capitalism is the air we breathe. Once you accept that, you have to ask yourself: what can you do to shift the trajectory, even slightly, and open up new possibilities?”

Cuff’s reflection echoed a point made earlier in the evening by Sarah Whiting, dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture at the GSD, who opened the event by emphasizing design schools’ ethical responsibilities—to their students, the profession, and humanity. “If we want our students to advance the world, making it more beautiful, more just, more ecological, and more durable, we need to work with them to envision what practices can enable that,” Whiting said. “As we push the envelope of building envelopes, facades, structures, materials, forms, and programs, we need to push the envelope of practice itself.”

In the end, Practicing Growth in a Finite World revealed less a crisis than a recalibration. The panelists’ insights traced an ethics of patience and pragmatism—an acknowledgment that meaningful change in the built environment unfolds not only through grand gestures, but through persistant, systemic work. In confronting the limits of growth, they offered a hopeful reminder: that design’s true power lies not only in what it creates, but in how it reimagines the conditions for collective progress.

Grafting the Aquarium

Overlooking the Boston Harbor on Central Wharf stands the New England Aquarium, a local landmark and an icon of Brutalist architecture. It is also the subject of “Grafting the Aquarium,” a studio course held during the spring 2025 semester at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) that addressed complex issues of climate change, aging building stock, and institutional transformation—themes critical to this aquarium and numerous others throughout the world.

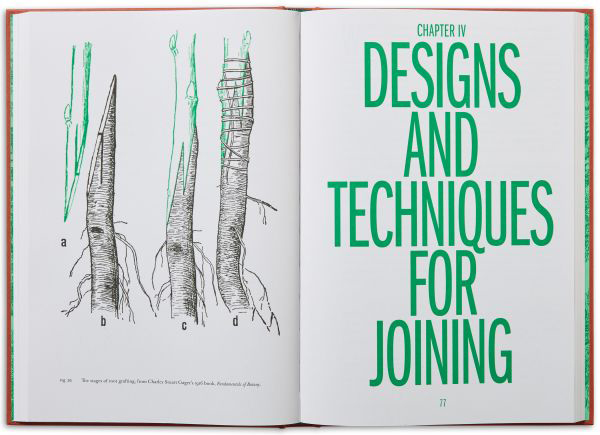

The studio’s name, “Grafting the Aquarium,” references the horticultural practice of grafting that has been embraced by Jeanne Gang (MArch ’93), founding partner of Studio Gang and professor in practice of architecture at the GSD, as a model for sustainable design and adaptive reuse. As described in her recent book The Art of Architectural Grafting (Park Books, 2024), “grafting is a design philosophy aimed at upcycling existing building stock by attaching new additions (scions) to old structures (rootstock) in a way that is advantageous to both. The practice of architectural grafting connects the two to create an expanded, flourishing, and distinctive work of architecture.” Rather than engage in the carbon-intensive cycle of demolishing existing buildings and rebuilding from scratch, grafting extends a structure’s life for greater capacity and utility. Taught by Gang and Eric Zuckerman (MArch ’18), project leader in Studio Gang’s New York City office, “Grafting the Aquarium” channeled this design approach to investigate possibilities for the New England Aquarium, a distinguished Boston organization with a celebrated past and an uncertain future.

The New England Aquarium, Then and Now

A cornerstone of the city’s waterfront revitalization plan, the New England Aquarium opened in 1969 to much fanfare. The robust concrete edifice, designed by Peter Chermayeff (MArch ’62) with Cambridge Seven Associates, sits a mere half mile from another Brutalist paragon, Boston City Hall (1963).1

The aquarium’s central feature, around which African and southern rockhopper penguins caper, is the cylindrical Giant Ocean Tank, 40-feet wide and four-stories tall, home to Caribbean marine life ranging in size from tiny reef fish to a 550-lb green sea turtle.2 Nearly five hundred thousand locals and tourists visited the aquarium the year after it opened; now, more than 1.3 million people annually frequent this regional attraction.

To accommodate more visitors and create space for new exhibits, the aquarium has grown in the past half-century, with the original building remaining largely untouched. The Marine Mammal Pavilion appended to the water-facing (east) facade accommodates sea lions; a metal-paneled addition to the west (by Schwartz/Silver Architects, completed in 1996) provides a harbor seal habitat, external ticketing windows, lobby, gift shop, café, and additional exhibit spaces; and the Simons IMAX Theater (2001), constructed on the southwestern portion of the wharf, boasts a six-story 3-D film screen and 378 seats.

Alongside these physical changes to its Central Wharf site, the New England Aquarium’s mission has evolved over the years, moving beyond the expectation for aquariums to serve, first and foremost, as venues for human entertainment. Aquariums previously offered a glimpse into elusive underwater realms; today, images and videos of these foreign ecosystems are accessible through the internet, with the click of a mouse. Furthermore, in recent decades, ethical concerns around keeping animals in captivity, especially incredibly sentient and intelligent species like dolphins and octopuses, have prompted shifts in aquarium programming, as has growing awareness of the deleterious impact of climate change on the ocean and its inhabitants. For these and other reasons, many aquariums—including the New England Aquarium—have become increasingly focused on research and conservation operations.

With this expanded scope come financial and spatial demands that exceed the limited facilities currently available at Central Wharf. Thus, the aquarium’s rescue and rehabilitation site in Quincy, 10 miles south of Boston, houses ethical breeding programs and acute care for injured animals (whether they be ailing residents or cold-stunned wild turtles). Another struture on the coast of Maine serves as homebase for a multi-decade North Atlantic Right Whale research project, one of the aquarium’s many marine science efforts. Mindful of the need for more revenue and additional space, aquarium leadership is keen to explore potentially advantageous programming and partnership opportunities beyond those that currently exist.

Underscoring the mandate for increased funding is the stark reality that the New England Aquarium’s Central Wharf properties require interventions to address the near- and long-term impacts of climate change—in particular, rising sea levels and storm surges. These days the aquarium experiences regular basement flooding, which threatens the animals’ mechanical and filtration life-support systems, and erosion around the Simons Theater’s foundational pilings requires mitigation. Recent resiliency planning calls for flood protection systems to withstand the inevitable tidal and storm flooding that will accompany the rising seas, predicted by 2050 to exceed four feet over current day levels. This knowledge goes hand in hand with climate-driven questions around how and when to protect against, accommodate, or retreat from the water. Consequently, in tandem with refining the institution’s mission and increasing revenue, aquarium officials must contend with aging buildings that need attention to remain operational and survive into the future.

Grafting the 21st-Century Aquarium

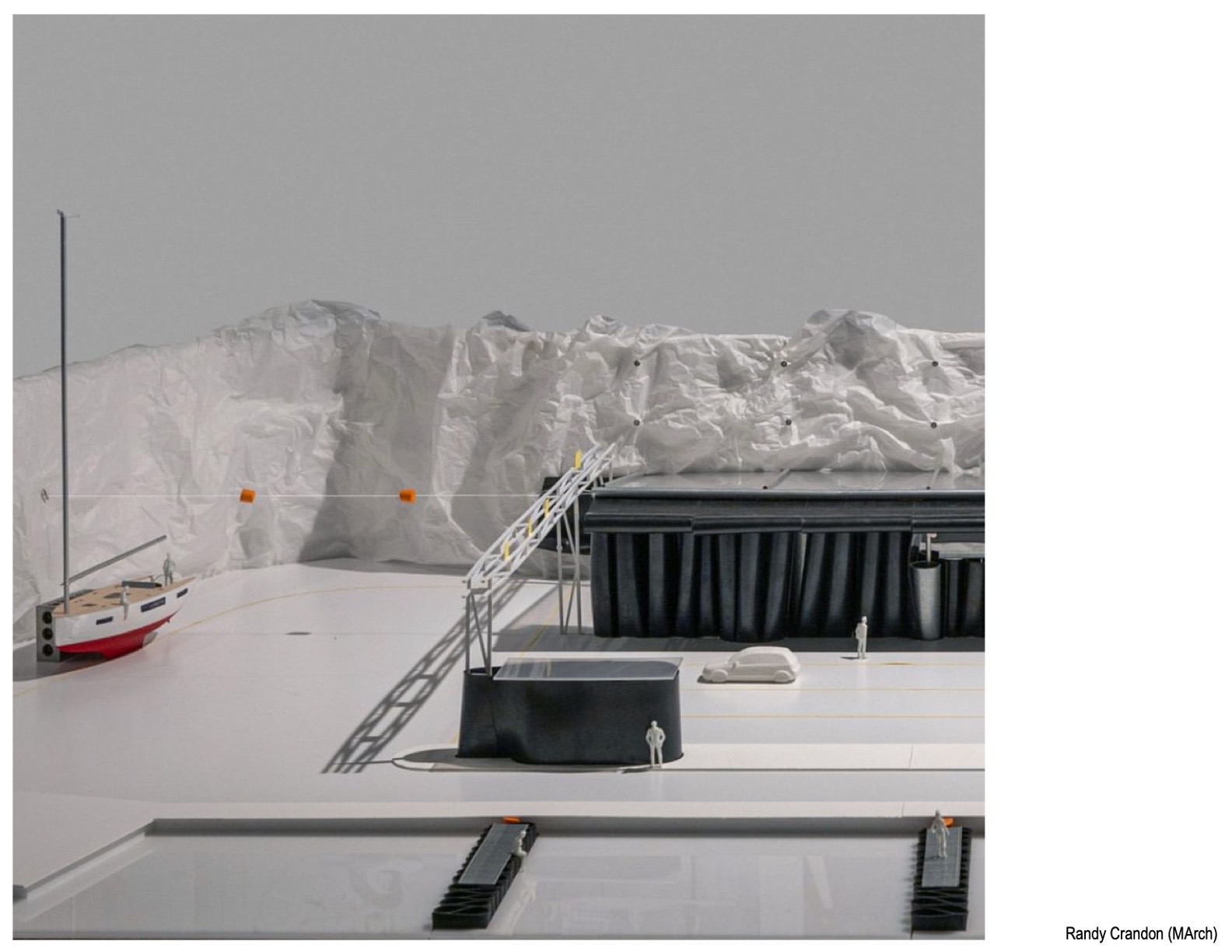

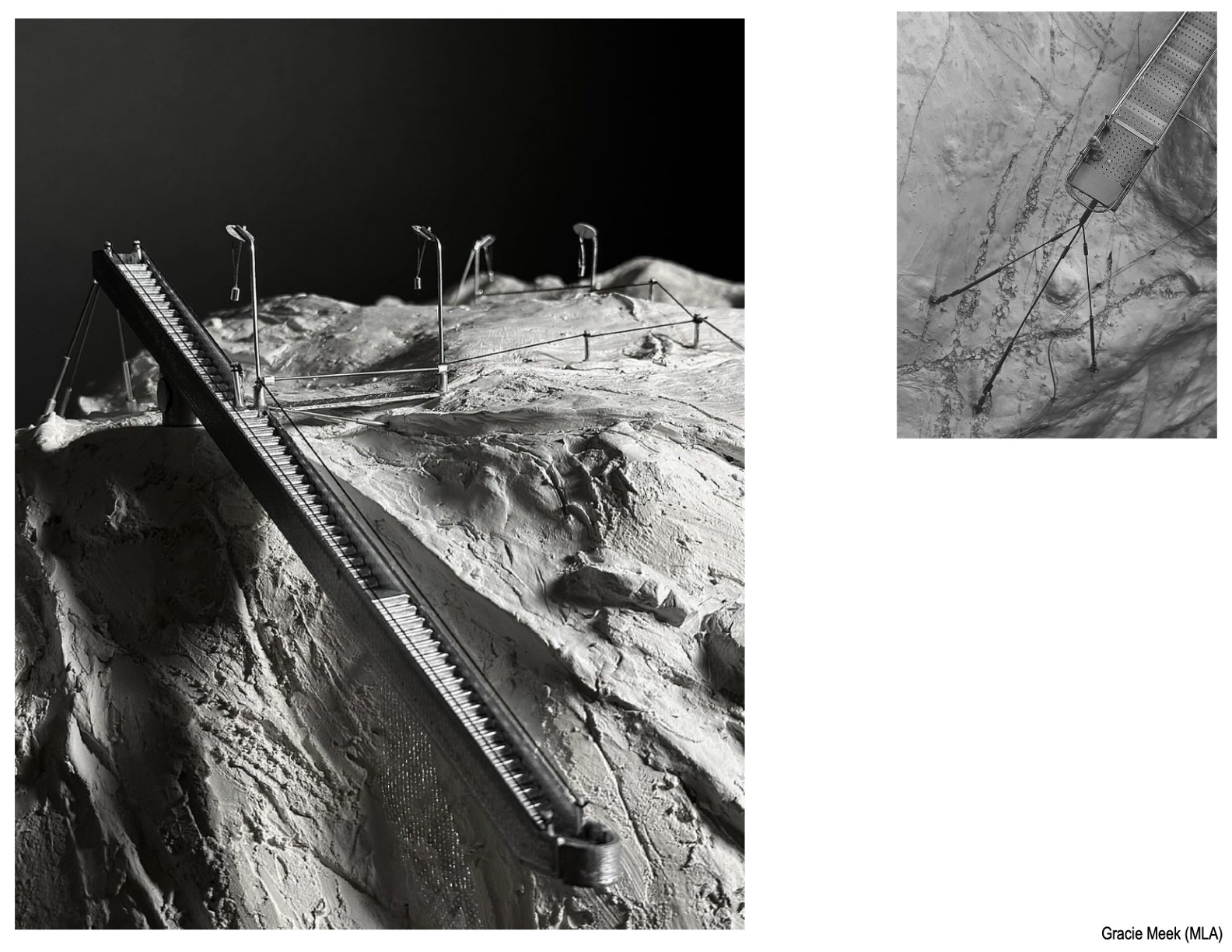

Under the guidance of Gang and Zuckerman, twelve GSD students from the master of architecture, landscape architecture, and urban design programs undertook an in-depth analysis of the New England Aquarium. Visits to its facilities, discussions with its leadership, targeted design exercises, and expert-led workshops informed the students about the aquarium and its site as they grappled with the complex themes surrounding the project, ranging from considerations of embodied carbon and vulnerability to sea level rise to designing for biodiversity and non-human species.

The main aquarium building posed an additional challenge. Consultations with Chermayeff provided rare insight into the design intent that shaped the concrete building, the first of the many aquariums in the architect’s portfolio. With its carefully choreographed interior circulation (winding around the Giant Ocean Tank) and its distinct, otherworldly interior (sans daylight, with strategic accent lighting), the New England Aquarium set the standard for Chermayeff’s aquariums that followed, including the National Aquarium (1981) in Baltimore, Maryland, and the Oceanarium (1998) in Lisbon, Portugal. Thus, as they devised their grafting operations to address the New England Aquarium’s future needs, students had to parse Chermayeff’s original vision for the building alongside its historic significance, material nature, environmental impact, and future needs.

As a design philosophy, architectural grafting is especially well suited to urban contexts, which are often marked by decades—if not centuries—of accretion. In her book, Gang notes that, in terms of environmental impact, “all renovations are better than building new. However, certain approaches prove more effective in reducing carbon pollution than others. In order to end greenhouse emissions in the critical period leading up to 2050, delaying the demolition of buildings saves the most carbon over any other single strategy, followed closely by increasing existing buildings’ intensity of use.”3 This holds true for the Brutalist New England Aquarium, making it and its Central Wharf campus perfect candidates for grafting. Following a strategic assessment of the existing site, the benefits it brings, and the challenges it faces, the designer then crafts sustainable solutions that honor the past, minimize carbon expenditure and waste, and build toward a resilient future. This compelling approach merges preservation and innovation to create a new whole greater than its parts.

Building on the concept of grafting, the students’ projects address climatic, economic, and spatial concerns, designs differ in terms of resiliency strategies, envisioned revenue streams, and physical interventions within the Central Wharf site.4 Yet, despite the diversity of approaches, the projects all position architecture as a key force in responding to these pressing issues and in shaping the New England Aquarium’s future. Whether establishing a greater connection with the city or the islands offshore, or highlighting education and animal care, the resulting designs foreground the aquarium as a steward of the marine environment and its resident species, the health of which impacts us all.

Diverse Approaches for a New Age

“Aquatic Symphony”

“Flood-Ready Common Ground”

“Landform to Islands”

“Spectacle & Care”

- Cambridge Seven continues to work with the New England Aquarium. ↩︎

- The aquarium opened in 1969, before completion of the Giant Ocean Tank, which became operational the following year. ↩︎

- Jeanne Gang, The Art of Architectural Grafting (Park Books, 2024), 17. ↩︎

- In May, the students presented their final designs at an end-of-semester review held at the GSD’s Gund Hall. Aside from Gang and Zuckerman, the jury during included Chermayeff, New England Aquarium vice-president of campus operations and facilities Ferris Batie, and GSD faculty members Iman Fayyad, assistant professor of architecture; David Fixler, lecturer in architecture; Stephen Gray, urban design program director; Gary Hilderbrand, Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in practice of landscape architecture; Toshiko Mori, Robert P. Hubbard Professor in architecture; and Chris Reed, professor in practice of landscape architecture and co-director of the master of landscape architecture in urban design program. Working in pairs or individually, the students proposed an array of design schemes for the New England Aquarium. ↩︎

When the High Tech Abounds, the Low Tech Shines: A Review of the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale

Across from the main entrance to the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale stands a courtyard lined with bamboo scaffolding. An ancient Chinese structure fashioned with lashed bamboo poles, such scaffolding dates back thousands of years and remains ubiquitous throughout Hong Kong, wherever construction is underway.

This particular bamboo scaffolding, erected in a Venetian courtyard, serves a different purpose: it is both set piece and enticement, part of a collateral event called Projecting Future Heritage: A Hong Kong Archive , curated by GSD alumni Fai Au (MDes ’11) and Ying Zhou (MArch ’07) with Sunnie Sy Lau. The scaffolding draws in visitors, showcasing its artful existence while leading to an adjacent warehouse-turned-gallery that catalogs examples of Hong Kong’s post-war building typologies and infrastructures.1 Employing natural materials and collective practices, the bamboo scaffolding evokes a sense of ingenuity and timelessness.

This year’s architecture biennale, also known as the 19th International Architecture Exhibition, carries the theme “Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective. ” Explaining this title, curator Carlo Ratti aligned the Latin intelligens with multiple forms of knowledge available to humankind. (Gens, after all, is Latin for people). Nevertheless, since the biennale opened last month, reviews—including “A Tech Bro Fever Dream” and “Can Robots Make the Perfect Aperol Spritz?” — have largely focused on the omnipresence of technology. True, the high tech abounds in a range of guises, from algae-infused building materials to sensor-ladened space skins. Yet, even as the dangling automatons and LiDAR maps underscore the “Artificial,” an expansive understanding of intelligence, one that embraces the “Natural” and the “Collective,” remains palpable, especially among contributions by members of the GSD community. This undercurrent surfaces through visitors’ “low tech” experiences with sensorial input, animal encounters, and communal engagement.

A Multisensory Biennale

The 2025 Architecture Biennale encompasses 300 installations, 66 National Pavilions, and 11 collateral events (as well as more than 100 GSD-affiliated contributors). Given this concentration of projects, one would anticipate an array of sights, sounds, scents, and atmospheric conditions. What appears striking, however, is the number of projects that rely on visitors’ immersive and multisensory involvement for full effect.

While most installations discourage hands-on interaction (“non toccare!”), tactile sensation nonetheless reigns supreme. This begins with Ratti’s main exhibition, staged primarily in the Arsenale’s Cordiere (a former rope factory/warehouse), which opens with the project Terms and Conditions . Here visitors move from the bright Venetian sunlight to a dim, muggy vestibule containing the waste heat from the air conditioning system that maintains the vast hall beyond at a comfortable 23 degrees Celsius (73.4 degrees Fahrenheit). The oppressive heat envelops visitors, offering them a glimpse of Venice’s projected future climatic conditions as they move beneath suspended air conditioning units, finally emerging into the Cordiere’s cool, light-filled, low-humidity interior where hundreds of exhibits await.

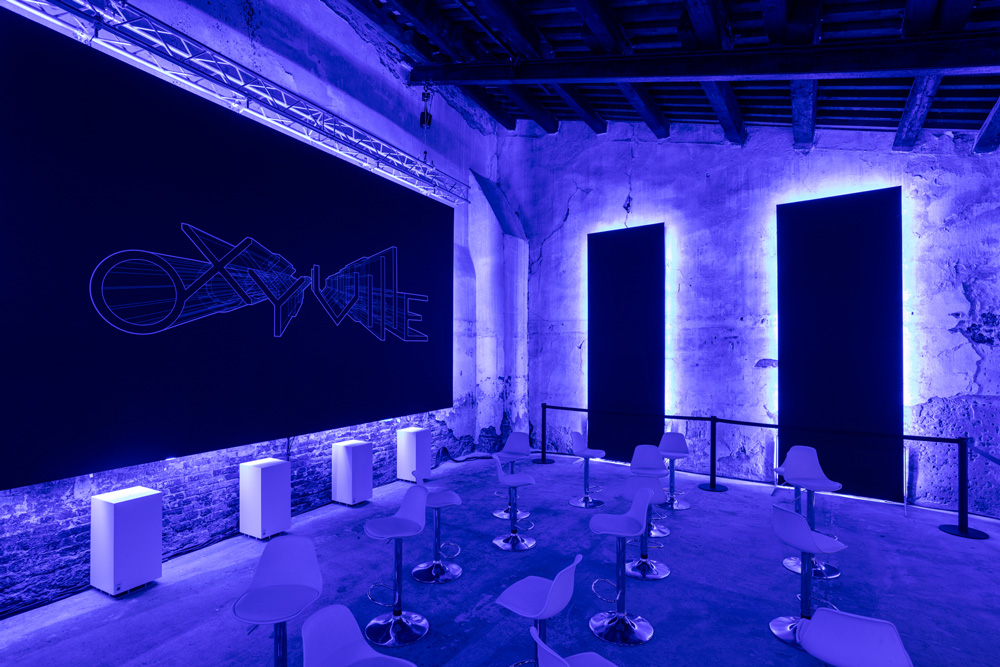

The immersive experiences continue with installations that cloak visitors in sound—dripping water; awe-inspiring music reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 Space Odyssey; humming frequencies, and more. One such exhibit—Oxyville by Jean-Michel Jarre, Maria Grazia Mattei, and GSD professor Antoine Picone—uses electronic music to explore the relationship between 3D audio and architecture. Within a space illuminated by glowing blue lights, visitors experience soundtracks that conjure different “sonic architectures,” such as that of a cathedral or, perhaps, a nightclub.

Other exhibits involve perceptible odors. Their inclusion isn’t necessarily intentional, although it is for some installations, such as Sound Greenfall and Grounded , the Türkiye Pavilion. Still, in many circumstances, discernable aromas become integral experiential components of a given project. For example, with its dense concentration of indoor microclimate-producing plants, Building Biospheres —the Belgium Pavilion, curated by GSD professor Bas Smets and Stefano Mancuso—proves incredibly fragrant. Meanwhile, the rectangular blocks of earth (chinampas) that populate Chinampa Veneta , the Mexico Pavilion, evoke the shallow-water environments in which these life-supporting landscape elements traditionally float.

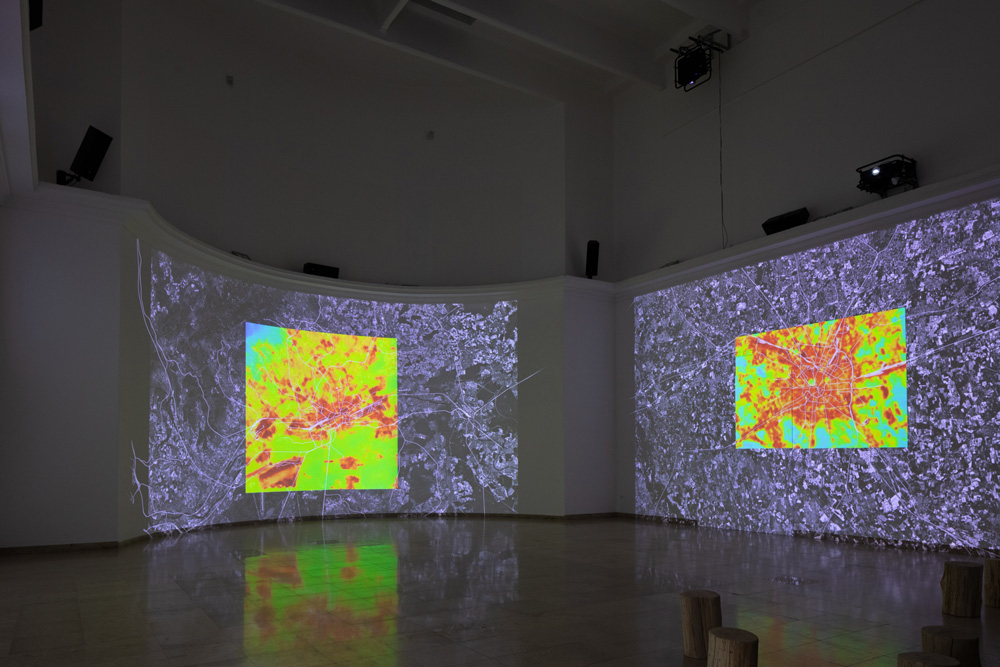

The exhibits are diverse visually, with intriguing dynamic elements and textured surfaces—smoke, water, lava, wood, vegetation—to catch one’s eye. Film features prominently, at times animating wrap-around enclosures to immerse visitors in the imagery. Stresstest , the German Pavilion (which includes a projects by GSD alumni Frank Barkow [MArch ’90], Regine Leibinger [MArch ’91], and design critic in landscape architecture Silvia Benedito [MAUD ’04]), employs this strategy, filling three walls of the pavilion’s soaring main space with infrared heat maps and alarming news footage of warming city centers. (A tolling bell—our planet’s death knell?—sounds in the background). Former GSD Loeb Fellow Tosin Oshinowo (LF ’25) harnesses a similar approach on a smaller scale for Alternative Urbanism: The Self-Organized Markets of Lagos . This installation’s screens surround visitors with the bustling activity of three Nigerian markets that recirculate so-called waste items from industrialized societies (clothing, auto parts, and more)—repairing, altering, and reusing them to create a sustainable system that transcends conventional patterns of consumption.

While planning the 19th International Architecture Exhibition, Ratti and his curatorial team no doubt recognized that all this sensory input could prove overwhelming. Perhaps this is one reason behind the minimalist AI descriptions that appear, in English and Italian, alongside the designers’ longer project explanations. Some may be disturbed by these pared-down depictions, at times a mere two sentences versus the designers’ original multi-paragraph text; have critical nuances been lost? Is this a commentary on the human attention span? Does architectural discourse really require such CliffsNotes? All these may well be the case. Yet, after experiencing a few dozen installations and realizing hundreds more await, it becomes clear that, whatever else they may be, the AI descriptions are a kindness, a “low-power mode” for visitors’ mental stamina as they undertake this endurance event. An added bonus: the AI text ruthlessly eliminates the discipline’s notorious archi-speak, in theory making the biennale more accessible to the public, including the mass of tourists who roam the Venetian cobblestone streets.

Animal Encounters

Aside from thieving seagulls and Piazza San Marco’s iconic winged lion, animals aren’t often associated with Venice, by said tourists or locals. A number of biennale installations seek to change this, including The Living Orders of Venice by Studio Gang, led by GSD professor Jeanne Gang. This project uses iNaturalist , a citizen science app, to enact a Biennale Bioblitz : a crowd-sourced field study to document local animal activity during the show’s 6-month run. In addition, the firm’s exhibit in the Cordiere showcases prototypical habitats to accommodate Venice’s non-human residents—the birds, bats, and bees displaced throughout centuries of construction, which destroyed their natural architectures. Instrumental for the planet’s health, these creatures require appropriate homes in increasing crowded urban centers, and Studio Gang proposes species-specific abodes to complement Venice’s existing classical architecture.

Architecture for animals likewise plays a role in Song of the Cricket , which models a rehabilitation effort for endangered species—in this case, the Adriatic Marbled Bush-Cricket, believed extinct for fifty years before its 1990s rediscovery in the wetlands of northeastern Italy. Alongside integrated research and monitoring programs, Song of the Cricket offers modular, floating islands as portable breeding stations that reintroduce healthy cricket populations to the Venetian Lagoon. Emblazoned with “BUSH-CRICKETS ON BOARD,” these temporary habitats support multiple cricket lifecycles, reducing threats of predation and disease. Other components of the project include a sound garden featuring the crickets’ song, described “as a bioindicator of ecosystem health,” unheard in Venice for over a century.

Similarly, animals emerge as crucial contributors in the Korea Pavilion, titled Little Toad, Little Toad: Unbuilding A Pavilion . With the project Overwriting, Overriding , exhibitor/GSD alumna Dammy Lee (MArch ’13) turns to the structure’s non-human occupants—a large honey locust tree and Mucca, “the [cow-spotted] cat who roams the space as if it were its own home”—to interrogate the pavilion’s history, highlighting the “hidden entities that have silently coexisted with the pavilion.” The installation 30 Million Years Under the Pavilion , by artist Yena Young, complements this narrative with a camera mounted beneath the structure to document unexpected visitors. The footage reveals that Giardini critters regularly frequent this and presumable all pavilions, which typically remain closed to the public when a biennale is not in session. (One is reminded of Remy the Cat, the unofficial GSD mascot who trapses through Gund Hall at will.) Thus the Korea Pavilion, built in 1995 yet reminiscent of Le Corbusier’s designs of the 1920s, serves as a home for not just the architects, artists, curators, and works they produce, but also cats (Mucca and two others), mice, birds, spiders, flies, and even a hedgehog—all cataloged by hand in pencil below wall-mounted Ipads that depict their visits. Amid the hi-tech fanfare that characterizes much of the 2025 Architecture Biennale, the ease, simplicity, and whimsy of Lee’s and Young’s projects, in conception and execution, feels particularly powerful.

The Power of Community

The Polish Pavilion, Lares and Penates: On Building a Sense of Security in Architecture , offers another commanding and clever presentation that shines among the National Pavilions. Infused with its own dose of whimsy, this exhibition zeros in on the ways in which architecture creates a sense of security, relying on two concepts from two very different communities: solutions derived from conventional building and health regulations, such as roofs, electrical codes, and evacuation signs; and others rooted in traditional Slavic cultural practices like brandishing dowsing (divining) rods to determine fortuitous home placement, installing horseshoes in doorways for luck, and burning smudge sticks to banish negative energy from a space. Lares and Penates, defensive household deities of Ancient Rome, lend their name to the exhibition while its designers present these security-bestowing practices as equally valid, complementary elements that, as a brochure accompanying the pavilion states, “help people feel more secure in a swiftly changing reality.” This non-judgmental approach is exemplified by the placement of a bright red fire extinguisher at the heart of a stone-and-shell encrusted niche. Fire codes, after all, are sacred in their own way.

While highlighting the human desire for security, the Polish Pavilion also alludes to our innate tendency to find strength in community, to connect with others to share ideas, resources, and support. Since its inception in 1980, Venice’s International Architecture Exhibition has embodied this urge for the cultivation of community on a global scale. That people today continue to congregate for the biennale, even though digitalization makes it possible to distribute knowledge without transcontinental trudging, indicates that many still yearn for actual (versus virtual) contact. Two installations openly address this impulse, as they provide platforms for present-day gathering and discussion. At the same time, they offer clear connections to the biennale’s communal past.

The Speakers’ Corner , by Christopher Hawthorne, former Loeb Fellow Florencia Rodriguez(LF ’14), and GSD design critics Sharon Johnston (MArch ’95) and Mark Lee (MArch ’95), who comprise the firm Johnston Marklee, offers a forum for workshops, lectures, and panels within the Cordiere. The inspiration for this sixty-person grandstand, made of unfinished white pine, stems from the 1980 Architecture Biennale—specifically, I Mostri d’Critici, curated by architectural historians/critics Charles Jencks, Christian Norberg-Shulz, and Vincent Scully, underscoring the disciplinary role of criticism and discourse. Throughout the 2025 biennale’s run, the Speakers’ Corner is hosting a series of events focused on future possibilities for architecture criticism—including those posed by the emerging role of artificial intelligence, as signaled by the biennale’s AI project descriptions.

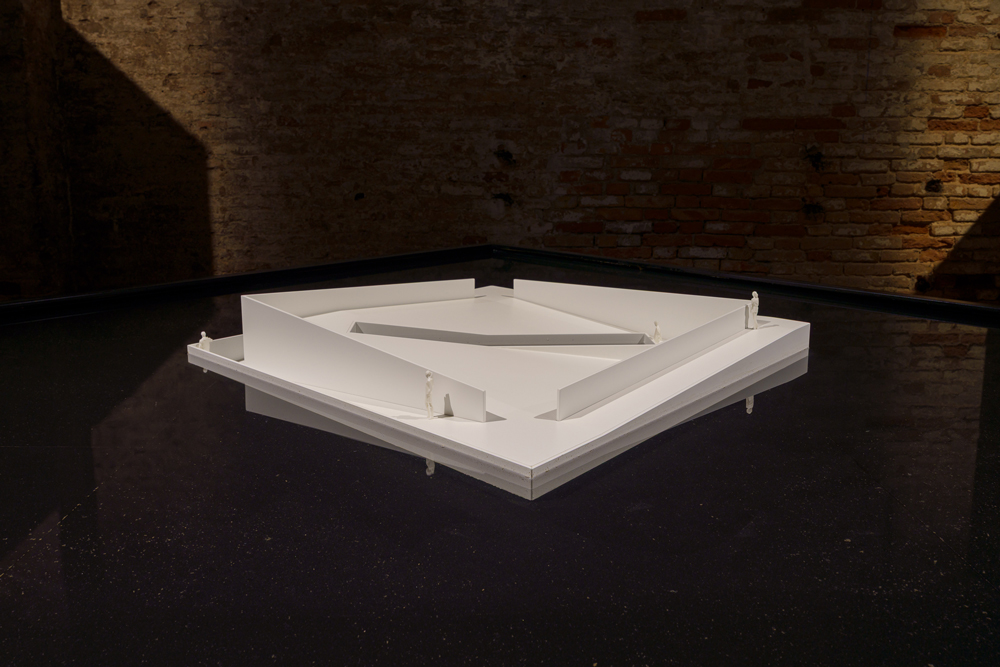

The other installation that highlights collective gathering and this biennale’s connection with the past is Aquapraça by CRA – Carlo Ratti Associati and Höweler + Yoon (founded by GSD professor Eric Höweler and alumna J. Meejin Yoon [MAUD ‘02]). Envisioned as a floating plaza to prompt discussions around climate change, this 400-square-meter entity will debut in the Venice Lagoon on September 4 before migrating across the Atlantic Ocean to join COP30 in Belém, Brazil, in November of this year. (A large model of the floating platform is currently on display in the Cordiere.) Aquapraça’s pure geometries recall those of Aldo Rossi’s Teatro del Mondo of 1979, a floating wooden theater that became an icon of the First Architecture Biennale before traveling via tugboat to Dubrovnik.

It is no accident that both the Speakers’ Corner and Aquapraça echo the aesthetic simplicity and communal intent of Rossi’s aquatic building. These projects illustrate the human desire to gather, to experience sights, sounds, and environments in real life. The sustained existence of the biennale attests to the continued significance of collective intelligence as well as creating places and events that bring people together.

- In addition to Fai Au (MDes ’11) and Ying Zhou (MArch ’07), Projecting Future Heritage includes many GSD affiliates. Jonathan Yeung (MArch ’20) and Wing Yuen (MArch ’22) are part of the curatorial team. Exhibitors include Max Hirsh (PhD ’12) and Dorothy Tang (MLA ’12) with Airport Urbanism: Remaking Hong Kong, 1975–2025; Su Chang (MArch ’17) and Frankie Au (MArch ’16) of Su Chang Design Research Office with Made in Kwun Tong: Between Type and Territory; and Betty Ng (MArch ’09), Chi Yan Chan (MArch ’08) and Juan Minguez (MArch ’08) of Collective with Pixelated Landscapes. ↩︎

Summer Reading 2025: Design Books by GSD Faculty and Alumni

Whether you plan to read in the summer sunshine or an air-conditioned lounge, these recent books by Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) faculty and alumni conjure environments from the semi-arid Mezquital Valley to the frozen Arctic tundra.

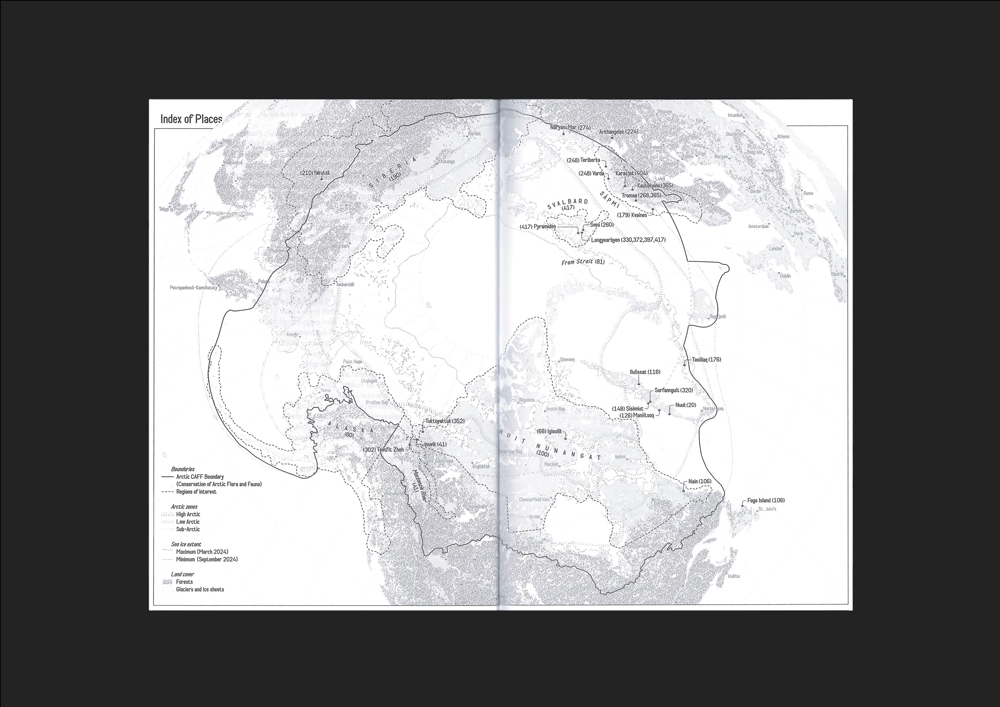

Arctic Practices: Design for a Changing World (Actar, 2025), edited by GSD lecturer in landscape architecture Bert De Jonghe (MDes ’21, DDes ’25) and Elise Misao Hunchuck, confronts two issues critical for Arctic lands: the climate crisis and the need for anticolonial reconciliation. Gathering texts by authors in the fields of design, education, and the arts, the collection offers diverse perspectives on current and future design interventions, all grounded within the Arctic’s distinct environmental and historical context.

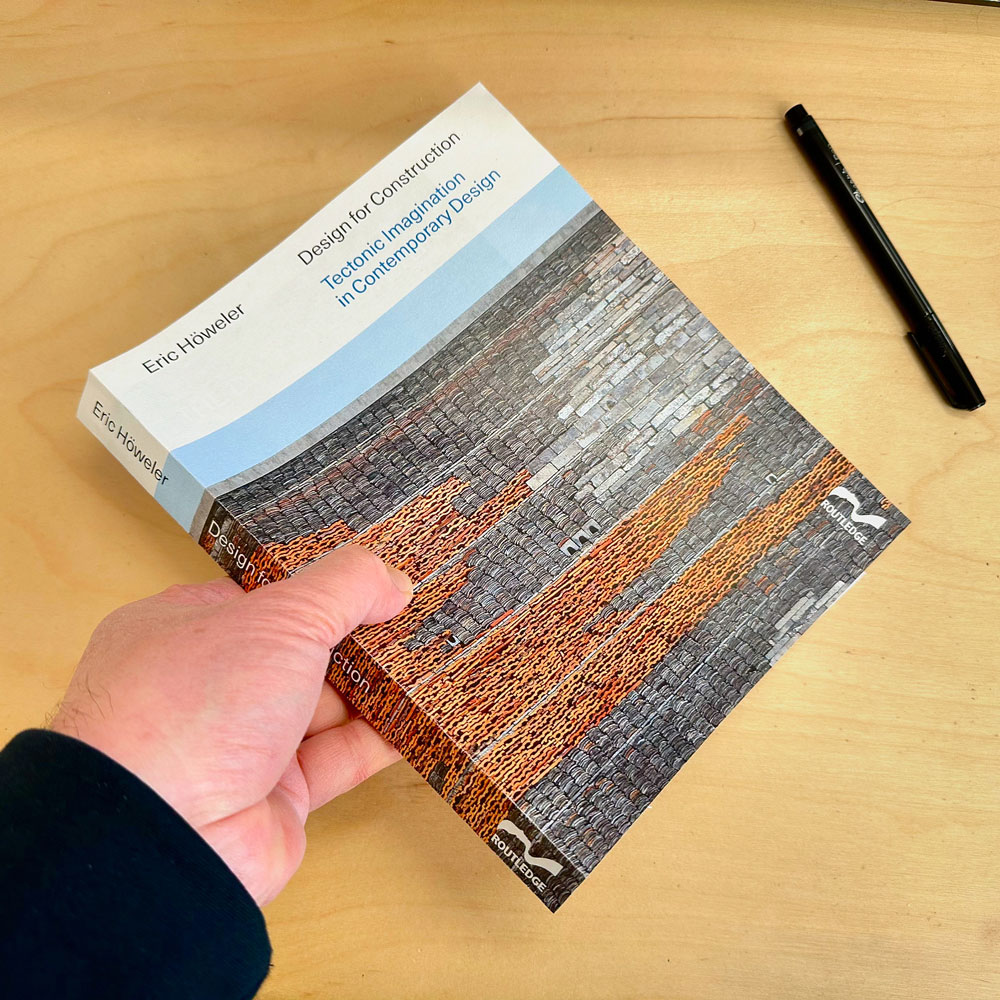

Design for Construction: Tectonic Imagination in Contemporary Architecture (Routledge, 2025), by Eric Höweler, professor of architecture and director of the Master of Architecture I program, bridges conceptual thinking and practical building techniques. The book delves into topics such as materials research and construction sequencing, dissecting projects by leading practitioners (including GSD-affiliates Barkow Leibinger, Johnston Marklee, MASS Design, NADAA, and others) as illustrative examples. As the discipline contends with its ecological and social impacts, re-engaging with design and building offers an opportunity for architects to assert agency while working toward a better future.

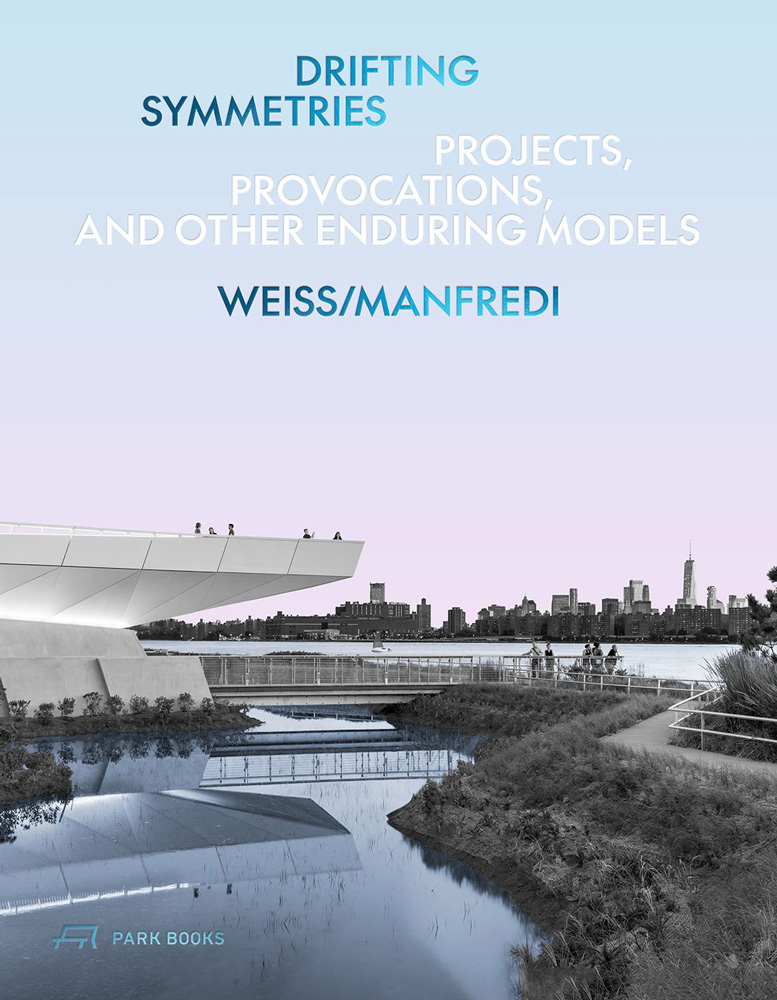

Drifting Symmetries: Projects, Provocations, and Other Enduring Models (Park Books, 2025), by Marion Weiss and Michael Manfredi, design critic in urban planning and design, features projects by the New York City–based architecture practice Weiss/Manfredi. Alongside the firm’s work—which is characterized by a multidisciplinary approach that melds architecture, landscape, and infrastructure—the book presents commentary from leading architects such as Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture Sarah Whiting, John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization Rahul Mehrota, Hashim Sarkis (MArch ’89, PhD ’95), Nader Tehrani (MAUD ’91), and Meejin Yoon (MAUD ’97), among others.

With the recent publication Hideo Sasaki: A Legacy of Collaborative Design, author Richard Galehouse (MCP ’61)—first Sasaki’s student at the GSD and later his business partner—traces the early development of Sasaki’s professional practice in the 1960s and 1970s. Through selected case studies Galehouse illustrates the legacy of design collaboration that Sasaki endowed to his professional practice—Sasaki —as it lives on today. In a distinguishing feature of the book, Sasaki speaks directly to the reader through excerpts from an interview conducted five years after his retirement.

All book proceeds support the Hideo Sasaki Foundation’s mission of equity in design.

Inside Architecture: A Design Journal (Balcony Press, 2025) by Scott Johnson (MArch ’75), FAIA, is structured as a personal and professional retrospective, offering a glimpse into the creative process of one of Los Angeles’s most accomplished architects. Combining candid narrative (including thoughts on his student years at the GSD), project case studies, and design commentary, Johnson reflects on the buildings, cities, and ideas that have shaped his decades-long career as the design partner and cofounder of the firm Johnson Fain.

Gareth Doherty (DDes ’10), associate professor of landscape architecture and affiliate of the Department of African and African American Studies, recently published Landscape Fieldwork: How Engaging the World Can Change Design (University of Virginia Press, 2025). This book challenges the discipline’s long-standing focus on the Global North and its current reliance on digital and technological solutions, offering tools for practitioners to engage more deeply with multidimensional, diverse landscapes and the communities that create, live in, and use them.

Landscape Is . . . !: Essays on the Meaning of Landscape (Routledge, 2025) explores various meanings of landscape as a discipline, profession, and medium. Edited by Gareth Doherty (DDes ’10), associate professor of landscape architecture and affiliate of the Department of African and African American Studies; and Charles Waldheim, John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture and co-director of the Master in Design Studies program, this collection is a companion volume to Is Landscape…?: Essays on the Identity of Landscape , released in 2016.

Thinking Through Soil: Wastewater Agriculture in the Mezquital Valley (Harvard Design Press, 2025), by former Dan Urban Kiley fellows Monserrat Bonvehi Rosich (2017–2018) and Seth Denizen (2019–2021), offers an analysis of the world’s largest wastewater agricultural system, located in the Mexico City–Mezquital hydrological region, to envision an improved future environment in central Mexico. This case study presents soil as an everchanging entity that is critical for the health of the planet and all its inhabitants.

Vembanad Lake and Its Untold Stories: Ecological Fragility, Food Sovereignty, and Sustenance Habitability (Notion Press, 2025), by Hasna Sal (MDes ’25), interrogates the historical evolution, ecological challenges, and socio-economic transformations of Vembanad Lake—the longest lake in India, and the largest in the state of Kerala—over the past century. Integrating cartographic and diagrammatic analysis with oral histories by fisherman, oceanographers, and more, the book advocates for a transdisciplinary framework that values localized, experiential knowledge as essential for designing inclusive conservation strategies that support environmental stewardship and social justice.

Rest Stops at the Top of the World

For the last 30 years, motorists in Norway have driven winding roads into the mountains and fjords along the country’s 18 National Scenic Routes , many of which skirt stunning coastlines, and are home to Arctic foxes, whales, and reindeer. Norway began developing these routes in the 1990s, by competitively selecting architects to design viewpoints and rest areas in the often fragile terrain. Now, with tourists flocking to witness the views—as well as the internationally renowned toilets, rest stops, viewing platforms, and other service facilities—and escape the quickly warming Mediterranean, the government faces the challenge of managing traffic along the narrow, winding roads, many of which, explains Luis Callejas, visiting professor in landscape architecture at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), were first traced in the eighteenth century for their views rather than efficiency.

In 2022, LCLA OFFICE , the firm Callejas directs together with Swedish-Norwegian architect Charlotte Hansson, was selected from an applicant pool of 81 design teams to develop sites on the Scenic Routes for the next six years. The beach where they’ll design a rest stop and bathroom is on the Lofoten Route , an archipelago above the Arctic Circle. With craggy, snow-topped peaks and shimmering teal-blue water, it remains in almost complete darkness all winter, except for frequent northern lights that draw visitors, and then becomes resplendent in 24-hour summer sunshine, a “paradise for arctic surfers, with fjords as the backdrop,” Callejas explained.

As part of his studio this spring, “Landscapes of the Norwegian Scenic Routes,” he traveled with GSD students throughout southern Norway, exploring some of the most important architectural designs along several routes with diverse landscapes, from wide sandy beaches to snowy fjords. Students have spent the semester creating their own speculative interventions, which Callejas says would need to endure under changing environmental conditions.

“One of the key questions of the studio,” he explained, “is how climate change and climate policies will affect the projects of the Scenic Routes.”

Callejas asked students to consider how their designs might marry environmental savvy with the durability the road conditions demand. And, because small communities along the Scenic Routes are impacted by tourists who arrive en masse each season, students’ sites must also lighten tourists’ impact—for example, limiting where they walk and directing how they spend their time during a rest stop—while allowing them to experience landscapes that are both magnificent and fragile. The paradox of the country, Callejas noted, is that it has “very sophisticated climate policies in terms of pollution and the standards in which infrastructures can be built,” but because it’s also geographically complex, it’s not connected by rail as are other European countries. Thus, rest stops need to include fill stations for today’s gas and electric cars, with the ability to be adapted for the near-future when all cars are electric.

The scenic routes are sections of roadways that were cleared hundreds of years ago, meandering through the country’s most beautiful landscapes, with narrow stretches etched into rocky fjords. Water constantly moves across the rock and roads, which can trigger disasters such as avalanches and floods. “Students learn that this is a design opportunity,” Callejas said, “as opposed to an engineering problem.” Additionally, the public is very sensitive to any visible interventions in the natural world, and will only accept well-designed solutions. This problem-solving, he says, is one of the elements of the studio that he most enjoys.

Students were tasked with designing three projects, the first without ever having visited Norway, a feat made possible thanks to what Callejas calls Norway’s “digital twin.” The country’s publicly accessible surveys map the land down to 20 points per square meter. He asks his students to consider “what happens when the digital twin is so high resolution that it starts to challenge the idea of direct experience as something that is always necessary?” Drawing a comparison to medicine, in which diagnoses can be made with scans and imaging, he argues that students can use sophisticated technologies to design from afar: “I’m interested to see what happens when the students suddenly come up with attitudes towards the landscape that the locals, who know the landscape very well, may not find as easily.”

Norway’s sophisticated roadway technology also includes an app with live cameras and a range of maps and alerts on road conditions and obstacles, from avalanches to animal crossings, facilitating travel along remote routes that change rapidly in the winter. Callejas’ studio required the app’s constant and updated road condition information to move through southern Norway this February, traveling about 1,500 miles from Oslo to Geilo, southwest to Stavanger, and back to Oslo.

Along the way, they stopped at the Allmannajuvet zinc mines, which were operational in the late 1800s and reinvented by Peter Zumthor & Partner as a café and gallery, with an available guided tour of the mine. They took in the impressive Vøringfossen , designed by Hølmebakk Øymo, and visited the whimsical “fairytale toilet” at Tryvefjora , designed by Helen & Hard, where a series of pine trunks support a concrete rooftop. This is one of many celebrated bathrooms that have attracted curious tourists along the scenic routes; at Stegastein , visitors can use a bathroom that juts out over a precipice.

With many projects on the routes relying on concrete and steel for durability, Callejas encouraged students to build without the “heavy handedness of the infrastructural works,” and to consider alternative materials. Students created rest stops at Jossingfjord, a site well known to Callejas as his team had already proposed a rest area there. The port is unique for its “landscape defined by the presence of ilmenite, a rock type similar to the composition of the moon,” he said, and “the raw matter for titanium dioxide.” It’s been mined from this area in Norway for nearly a century.

For his part, Callejas is at work on the Lofoten beach rest area. With so many visitors arriving by car and van year-round, the roadway commission has asked Callejas’ firm to design a new public bathroom, which will need to be durable in the face of the beach’s “beautiful white sand” that will pummel it all year long. LCLA OFFICE will also design a space for “wind protection and perhaps even overnight shelter,” with access to a potable water source.

The building will be constructed of raw aluminum by local ship builders, as the area doesn’t have a traditional construction work force. Treated with a “sandblast gradient” to make the aluminum appear weather-worn, the structure will be reminiscent of the silos that still stand from the region’s industrial days. Today, at Lofoten beach, travelers might spot otters, puffins, cormorants, and dolphins—just some of the wildlife protected by Norway and accessible along age-old roads that now boast some of the region’s most interesting contemporary architecture.

When the Client is a Nation

Inside the Peabody Museum on a windy October day, leaders of the Sac and Fox Nation peered into the eyes of their ancestor, William Jones , the second Indigenous person to graduate from Harvard, in 1901. Posed in a cap and gown, Jones’s black-and-white photographs sit under a glass case beside a pair of beaded moccasins.

“He’s almost as good-looking as I am,” Principal Chief Randle Carter joked with Robert Williamson. Carter and Williamson had traveled to Harvard from Oklahoma, where Jones was born in 1871 and the tribe is based today.

The Sac and Fox are one of 574 Native tribes who operate as nations within a nation; they have the right to self-governance and maintain their own political systems . Williamson and Carter were invited to Harvard by Eric Henson, a lecturer in Urban Planning and Design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and a longstanding member of the Harvard Project on Indigenous Governance and Development , which helps Indigenous nations worldwide strengthen their governance systems. Henson’s Fall 2024 GSD course, “Native Nations and Contemporary Land Use”, brought together GSD students with representatives of the Sac and Fox—along with the tribe’s collaborator, a professional hockey team—to help the tribes meet their goals to regain sovereignty over their ancestral lands in Illinois.

“With a focus on land use, landback initiatives, and economic development opportunities,” writes Henson, “the course provides in-depth, hands-on exposure to how Native people are addressing these issues today.” Landback initiatives have been underway since the colonial era but only became widely known as such in the last few years. Part of Native nations’ work towards claiming their sovereignty, landback focuses on a number of initiatives, including acquiring land that was stolen from them throughout the process of colonization.

“If you’re building something new, or designing a park,” said Henson, explaining the importance of learning Indigenous history at a design school, “you have these steps you are supposed to check off: Did we do this review? Did we look for artifacts or archaeological dig sites? I’d like to see a degree of understanding beyond that. It’s not just a box to check off. You’re talking about real people who are victims of genocide and war and outright theft of their traditional territory. Taking a few minutes talking to a tribal leader before starting a design might open your eyes to the place in which you’re doing that work.”

For example, he says, in Bendigo, a town north of Melbourne, Australia, town leaders collaborated with the Dja Dja Wurrung , the Indigenous community, to incorporate Native design elements, revitalizing the town and attracting more investors. Henson noted that there are Native design elements in many buildings in Bendigo, which offers a model for others to follow.

This semester, students are working with two Indigenous Nations. Henson, a Chickasaw citizen, draws from his deep contacts with tribes around the US who have requested to work with him and his classes. The course Henson teaches at the Kennedy School , Nation Building II/Native Americans in the Twenty-First Century, offers collaborations with Indigenous Nations and now serves as a companion to the course at the GSD, with projects carrying over from one to the other. The course at the Kennedy School is cross-listed with the GSD, the Faculty of Arts and Science, the Graduate School of Education, and the Chan School of Public Health.

“With more education around Indigenous history, culture, and design, there could be tremendous collaboration between designers and Indigenous nations,” Henson argued, “with Indigenous design elements incorporated. In addition, non-Native communities that neighbor tribal lands have great opportunities, if they want to embrace them and work with tribes.” Not least of which, Henson explained, is the tribes’ access to federal funding and their role as major employers, particularly in rural areas.

This mutually beneficial relationship is what Rahul Mehrotra hoped for when he suggested a Native-focused GSD course to Henson in 2020, when Mehrotra was chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design. Henson collaborated with Philip DeLoria and Daniel D’Oca to design an interdisciplinary GSD class they called “Land Loss, Reclamation, and Stewardship.”

“In the context of discussions at the GSD on diverse ways of understanding history, and in the context of climate change,” said Mehrotra, “learning from traditional practices is very important. The relationship that Native Americans have to the land, and to nature more broadly, is sensitive, beautiful, poetic, and empathetic—and incredibly intelligent.”

GSD students’ work impacts the lived environment around the world, Mehrotra explained, and with more education about Indigenous people and their history, design students’ sensibilities would invariably shift.

“I wanted the Indigenous studies course to have history, design, and practice components,” said Mehrotra, “so that students would have a sense of what they can learn from history and traditional practices as they intersect with design.”

This past fall in Henson’s course, GSD students Cayden Abu-Arja (MArch I / MUP ’27) and Neady Oduor (MDes ’26) opted to work with Carter and Williamson to design a program to help them regain their ancestral lands, which the tribe determined was one of their primary goals.

“Our traditional lands,” Williamson explained, “are not in Oklahoma.”

For 12,000 years, the two tribes, then known as Sauk (now Sac), the Yellow Earth People, and Meswaki (Fox), the Red Earth People inhabited the area around Quebec, Montreal, and eastern New York state, but were forced southwest by the Iroquois, and then further west by the French. The two tribes banded together and moved to Illinois, establishing their summer village in Saukenuk, today known as Rock Island, along the Mississippi River. There, they planted 800 acres of corn, vegetables, and fruit to feed the almost 5,000 people in the well-organized community.

Abu-Arja and Oduor quoted tribal leader Black Hawk’s autobiography, in which he describes his memories of that place: “It was our garden (like the white people have near their big villages) which supplied us with strawberries, gooseberries, plums, apples, and nuts of different kinds, and its waters supplied us with fine fish, being situated in the rapids of the river.” Black Hawk recalled spending his childhood summers on the island, surounded by family.

In 1804, colonists tricked the Sac and Fox chief into signing a treaty that gave the land to Illinois, forcing the tribe off their summer grounds to the west of the Mississippi. By 1832, with the Sac and Fox people starving, Black Hawk led the community back to Saukenuk to plant their traditional summer crops.

“After years of encroachments from the US government,” said Williamson, “this was Black Hawk saying, ‘I want to go home.’” Instead, said Williamson, the Illinois militia “slaughtered women, children, and older men” over the course of more than three months, in what colonists called the Black Hawk War. The Sac and Fox were subsequently pushed further west again, this time to Oklahoma, where they live today and continue to fight for access to their ancestral lands.

Landback Initiatives & Innovative Collaborations

At the beginning of January, another tribe, the Prairie Band Potawatomi , were approved by the Illinois State House to receive a land transfer of 1,400 acres, which makes up Shabbona Lake State Park, named for Chief Shab-eh-nay. The government sold the land illegally in 1849, violating a treaty the Prairie Band had signed 20 years earlier. The Potawatomi have agreed to continue allowing public access to the park, which will be maintained by the state.

Tribes across the US have undertaken landback initiatives in different ways, from acquiring the land through private purchase to lobbying for it from state lands or through estate planning. For the Sac and Fox, a Nation with about 4,000 members, the goal is to follow the lead of the Potawatomi to reestablish their footing back in Illinois around the site of Saukenuk village. Today, Illinois maintains Black Hawk Historic Site on the tribe’s ancestral lands, with a statue of the warrior, a small museum that describes Saukenuk, and a 100-acre nature preserve. Williamson noted that, like many other Indigenous US tribes, their leaders’ names have been used for streets, towns, professional sports teams, and even army helicopters. They deserve to have access to their ancestral lands.

Joining Carter and Williamson on their trip to Illinois were representatives from the Blackhawks Hockey team, whose CEO, Danny Wirtz, has invited the nation to collaborate in ways the Sac and Fox choose. While many Indigenous advocates have argued for professional sports teams to change their name, Wirtz suggests that the collaborative work he and his team are doing with the Sac and Fox requires more authentically engaging with one another. The tribe voted to work with the hockey team and is prioritizing economic development, strategic planning (including landback initiatives), and language preservation projects.

“Our partnership with Black Hawks’ tribe, the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma,” says Sara Guderyahn, the Chicago Blackhawk’s Executive Director, “is centered around education and cultural preservation with the goal of supporting the Nation’s priorities for sovereignty. To that end, we are excited and optimistic that this project is an important step to explore opportunities for the Nation to reconnect with their original homelands in Illinois.”

GSD students Abu-Arja and Oduor began their work with the Sac and Fox by learning about the tribe’s history, including their forced migration through the US, Black Hawk’s leadership, and the Nation’s ancestral lands. The group’s visit to the Peabody Museum with Carter and Williamson highlighted the Sac and Fox’s most famous members: anthropologist William Jones, whose photos and writings they viewed alongside the leaders at the museum and in the archives, and football player Jim Thorpe, who won two Olympic gold medals in 1912.

“When you look at the record books,” said Chief Carter, “Thorpe was not a citizen of the US. Before 1924, Indian people were not citizens of the United States. The record should say he was a citizen of the Sac and Fox Nation.”

Henson led the group to visit a site on Harvard’s campus that brings Thorpe’s legacy back to contemporary material culture. At what’s now Clover Food Lab , the ceiling tiles that depict the early twentieth-century Harvard football league pennant flags include the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. When Jim Thorpe led Carlisle to defeat Harvard in 1911, the Indian School was cut from the league; Harvard never played them again. The Indian Industrial school was part of the US government’s attempt to erase Indigenous culture through the forced removal of thousands of children from their homes and families, under the motto “kill the Indian, save the Man.” When the tiles were uncovered on Massachusetts Avenue, right across from Harvard’s gates, in a 2016 renovation , they restored to the record in Cambridge the story of Jim Thorpe at Carlisle, before he went on to win Olympic gold medals.

The group’s visit to the site was part of a tour Henson led, which was originally designed by Jordan Clark, Executive Director of the Harvard University Native American Program (HUNAP) and a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Aquinnah. The tour makes visible the Indigenous histories that are often missed all around us.

For example, Henson pointed out a plaque on the side of Matthews Hall, commemorating the history of Harvard’s Indian College— founded by missionaries in the 1640s—whose bricks were eventually dismantled to build other Harvard structures. Henson pointed to a spot on the lawn beside Matthews Hall, where a 1990s archeological dig revealed pieces of the press used to print the Eliot Bible, written in Algonquin (a language of Indigenous tribes), the first Bible printed in the US, now held at the Houghton Library . Henson noted the plaque on the president’s house that names the enslaved people who labored there, and the rusty pump in the center of the yard, which marks the water source from which Massachusett and other Indigenous people were cut off when settlers claimed the site.

Making Indigenous histories visible, highlighting how their stories predate colonization by thousands of years, as well as how they are irrevocably intertwined with Harvard’s history, helps to make tangible the ethos of the land acknowledgment that the GSD wrote in collaboration with HUNAP and reads at the beginning of every public event.

Strategies to Educate the Public and Regain Access to Saukenuk

After learning the histories of Indigenous nations in the east and midwest, Abu-Arja and Oduor focused on designing a program centered on “co-management” of the Black Hawk State Historic Site, which they say the Sac and Fox Nation “sees…as a way to connect with their ancestral homeland…and pass on traditions (some of which were lost when they were removed from their land).” The team outlined three goals: 1) creating storytelling opportunities so that people understand the “social and cultural significance of the Black Hawk State Historic Site” to the Sac and Fox Nation, 2) developing revenue streams, and 3) increasing collaboration with Illinois state.

They defined 15 different activities, from collaborating with the Sac and Fox to develop new exhibits at the existing historic site museum, to building clan houses for cultural activities, hosting riverside storytelling sessions and ceremonies, creating a gift shop, and “tailoring [the tribe’s existing language programs] to young students who visit the site.” They note that the Nation can turn to existing protections, for example, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which would support co-managing the cemetery where Black Hawk’s children are buried but remain unnamed on signage that commemorates settlers. As precedent for managing burial grounds, they cite Minnesota’s Indian Mounds Regional Park, which was developed around the gravesites of several tribal nations to protect the mounds and share their people’s histories. By increasing the public’s knowledge of and engagement with the Sac and Fox Nation, as well as collaborating with the state government, the Sac and Fox’s case for landback will become more visible—and therefore, more viable.

At the end of the semester, Abu-Arja and Oduor presented their proposals to the Sac and Fox Nation, who are moving ahead with their plans to develop the programs in Illinois, which they hope will bring them one step closer in their two-hundred-year battle, starting with their ancestor Black Hawk, to regain their lands.

Forests Are Cultural Constructs

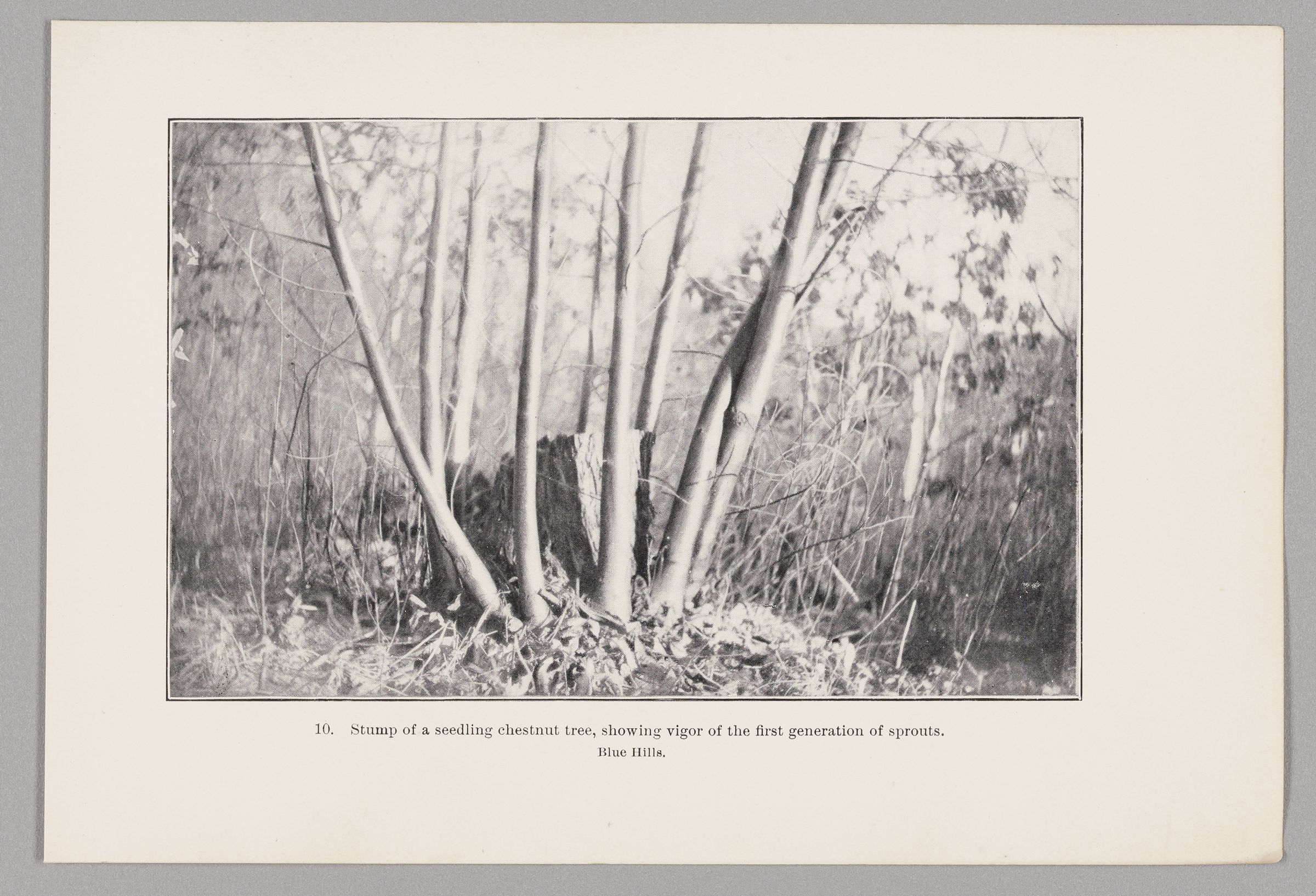

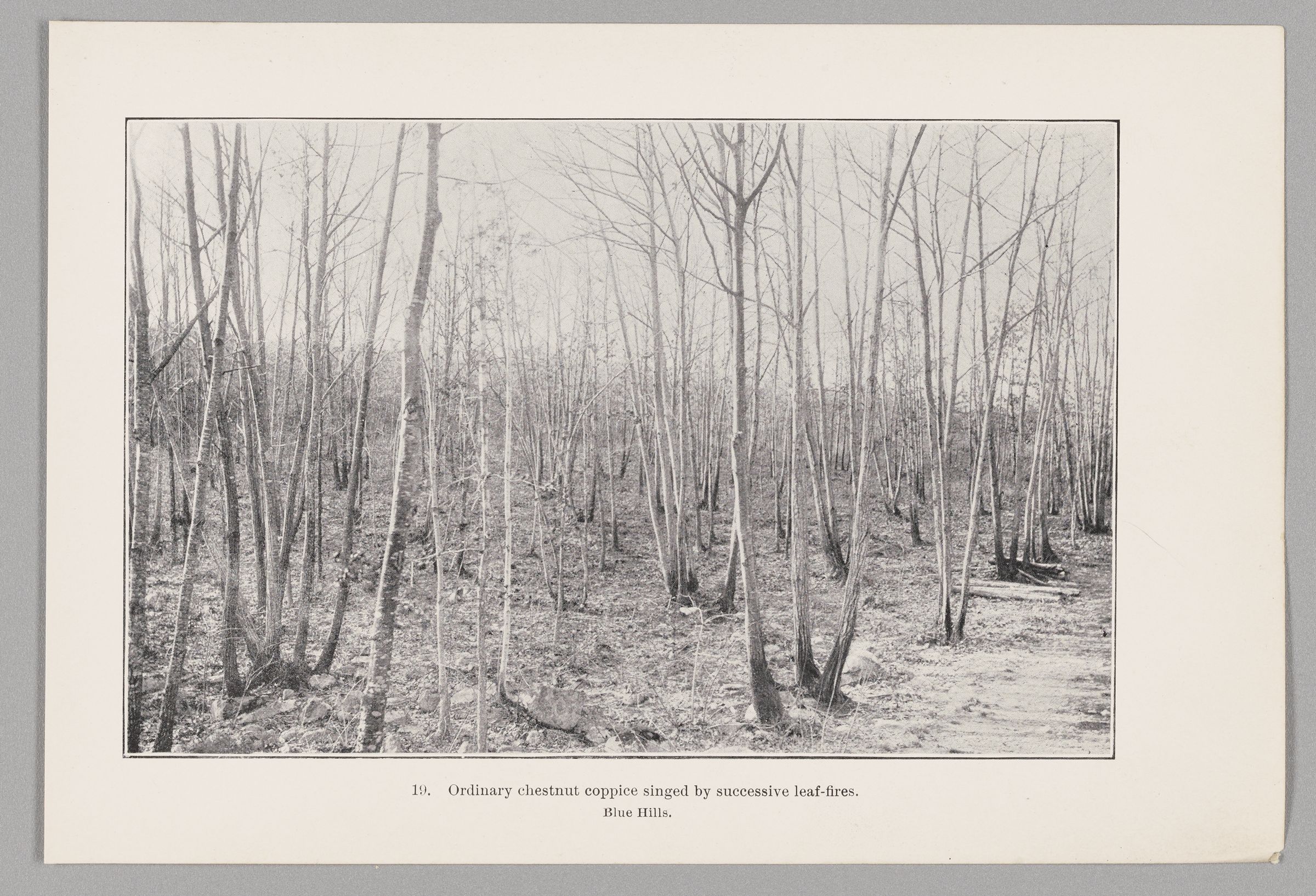

One hundred thirty years ago, environmentalist and landscape architect Charles Eliot walked the Blue Hills, a vast green swath south of Boston, envisioning its transformation into a wilderness reserve. Looking out to the horizon from the hill’s peak, he saw not a wild forest but hundreds of thousands of coppices— clusters of sprouting trunks created by cutting a tree close to the ground and causing it to release what Anita Berrizbeitia calls “repressed buds” that wait beneath the bark. Walking the same hills Eliot traversed all those years ago, and in the process of researching the wilderness’ origins in archives, Berrizbeitia was surprised to find that Eliot’s Blue Hills reservation plan emerged out of an agricultural forest that provided lumber for settlers for two hundred years, and that he proposed to remove more than 400,000 coppiced trees by using grazing sheep to prevent the sprouts from developing, and then lifting the roots systems out of the ground by hand, one by one—a laborious, time-consuming process.

Her research of the Blue Hills led Berrizbeitia, professor of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), to consider what makes a forest “wild,” how all forests are culturally constructed, and how our contemporary landscape honors or erases indigenous history. These are the themes that she’s now exploring with her students in “Forests: Histories and Future Narratives,” a course that follows on the heels of Forest Futures, the exhibition she curated at the GSD last spring.

In temperate forests, write Rob Jarman and Pieter D. Kofman in Coppice Forests in Europe, “simple coppicing” can be achieved in mid-winter, when the tree is dormant. Cut the tree near the base, and then, come spring, explains Berrizbeitia, “the energy previously spent on the canopy and the leaves but now entirely contained in the root system is reassigned to dormant buds contained in the remaining stump or in the roots.” The trunk sends up “vigorous growth of straight poles within a short span of time.” The new shoots can be cut at whatever size is required for the lumber’s purpose (firewood, construction, furniture, etc.), and can be harvested over and over again for decades—even centuries—from every three to 30 years. “In a coppice system, the roots remain alive and productive for hundreds of years,” says Berrizbeitia. “Historian Oliver Rackham refers to this phenomenon as the ‘Constant Spring.’” Coppiced trees in England have survived for two thousand years and hold in their trunks valuable information about the past. Kofman and Jarman note that coppices “of all kinds and ages are of interest for their associated wildlife and for their cultural heritage.” Some plant and animal species need the “open spaces…, edge habitats and alternate light and shade conditions” that coppices, as opposed to the thick overstories tall trees, provide.

In attempting to transform an agricultural forest into a recreational one, Charles Eliot confronted questions about what makes a forest and how cultures are reflected in those landscapes.

Thousands of years before colonists arrived in New England, the Massachusett nation inhabited the region we refer to as “The Blue Hills.” In fact, “Massachusett” means “people of the Great Hills.” For 8,000 years before European contact in the 1600s, the indigenous nation farmed corn, squash, and beans; used trees for their fuel, wetus, and canoes; and, says Berrizbeitia, “walked through the valleys on their way to the Neponset River, to fish and to transport material to the shore, or to return to their fields of corn in the meadows of Quincy, or to their village on the borders of Ponkapoag bog.” They had access to wild game for meat and furs, as well as valuable mines from which, for thousands of years, they drew granite and “rhyolite, a volcanic rock with high silica content” to “make sharp tools and spears.”

When European colonists arrived in 1620, like all tribes along the east coast, the Massachusett had just suffered through a plague, and, in the decades that followed, struggled to maintain their lands in the face of the thousands of Europeans who arrived on their shores. They were removed from the Blue Hills to Ponkapoag, where, today, they write, “we continue to survive as Massachusett people because we have retained the oral tradition of storytelling just as our ancestors did.”

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, settlers clear-cut the forests, taking first the white pines, whose strong trunks made excellent sailboat masts. They turned over thousands of New England acres of rocky soil, built stone walls to mark their property, and planted crops to feed the colonies— often with the forced labor of enslaved Africans and indigenous people whose land the colonists stole.

Berrizbeitia surmises that, in the late 1800s, Eliot knew about the Epping Forest in England, where pollarded trees (created in the same way as coppices, but cut higher up their trunks) had been harvested for centuries and inspired a debate among residents and experts: Should the coppiced trees remain or be removed? What should this new forest look like? Designer and social activist William Morris argued that the coppices represented an important part of the cultural history of the region, and vehemently opposed biologist Alfred Russell Wallace’s proposal to import trees from other nations (including the US and China) to help diversify the English forest. This first attempt to apply biogeographic diversity to design was rejected, and the pollarded trees remained. They can be found there today, in tall clusters, evidence of the forest’s history.

In the Blue Hills, says Berrizbeitia, Eliot noticed seedlings growing between the coppices. He knew that, if left to its own devices, the forest would regenerate. He was right—but, frequent forest fires prevented the natural regeneration of the forest.

The Massachusetts government decided they had to intervene. “They realized, ‘we devastated our soils with agriculture.’ What’s going to happen to us?” To jumpstart a new succession cycle, as the regeneration process is called, they planted white pines in large numbers, adding over one and a half million in the Blue Hills. This is a practice the US forest service continues today, planting pines and other trees throughout the US, an aspect of silviculture—a word coined in the late nineteenth century, when Eliot was hard at work on the park system.

All along the outskirts of Boston, the lands Eliot developed into the Metropolitan Park system were full of coppiced forests, the primary source of fuel in the area until the transition to coal took place in the 1880s. Instead of remnant wilderness, these were fallowlands, abandoned forests that needed to be put to a different use. He likely began his project to remove the coppiced trees, Berrizbeitia theorizes, but soon enough, the gypsy moth and chestnut blight took hold in the area, killing the coppiced trees. Thousands of new trees—a variety of species—were brought in from nearby nurseries, and when those failed, more were planted. Berrizbeitia is now researching the infrastructure that drove the transformation of the Blue Hills—including where those millions of pine seedlings were cultivated, and how they were transported and stored.

She argues that Eliot’s proposal to remove the coppiced trees was an attempt to erase the imprint of settler’s colonization of the Massachusett people’s land, and that although he knew the importance of the hills to the indigenous nation, he did nothing to recognize them beyond the naming of landmarks.

In the face of the current environmental crisis that requires a transition from fossil fuels to renewable and diverse energy sources, coppicing has reentered the conversation on sustainable resources. Combined with other energy sources, such as solar and wind power, says Berrizbeitia, it’s possible that harvesting lumber with coppicing techniques could become another energy resource. Although still widely used in Europe, coppicing is now experiencing a revival in the US. Berrizbeitia’s research on the Blue Hills restores to the region the story of a designed forest whose history might help us move into an uncertain future with more tools at hand.

The Body in Intimate Spaces

The bathroom is inevitably a space where we find ourselves spending time each day, and yet, say Laila Seewang and Chris Reed, its impact on urban space is often overlooked in terms of design. The studio Seewang and Reed are leading this semester, “FLUSH: Waste and Intimacy in Berlin’s Civic Realm,” explores issues around water supply and sewage systems and how intimate spaces—such as bathrooms, public pools, or showers—are connected with these larger urban systems. Seewang, visiting assistant professor of urban planning and design, and Reed, co-director of the Master of Landscape Architecture in Urban Design degree program and professor in practice of landscape architecture, collaborated on the interdisciplinary course that brought students to Berlin to learn more about the history of resource landscapes, such as the “sewage farms” that filtered urban waste, and how they might respond to these leftover spaces today.

Rachel May: How did you create the FLUSH studio?

Laila Seewang: The city of Berlin had the first municipal water system that flushed out a whole city’s wastewater onto sewage farms, primarily because it’s not near the sea. It was a city-scaled experiment in water circularity. The work stems from my doctoral research that examined the history of that system.

The studio is about the legacies of public sanitation—for example, what it means when, as a public responsibility, a city decides to provide water to its citizens and take away sewage. It’s one of those things that we take for granted as a sign of modernity: in developed cities today, we expect clean, free, running water and someone taking away the waste. But, how we came to those decisions is not always clear.

We gave this history to the students as a prompt. It’s a way of asking them to think about issues such as: Who has rights to resources—and are they evenly distributed? How are they channeled? What do we give up in exchange? How do our bodies use that water? How does the community need to use it? What spaces does that create in an urban landscape?

Chris Reed: I was looking at some of the drawings developed at the time that the sewage and water systems were being designed, and the movement toward public toilets was underway. There’s very clear thinking about relationships between, say, the point of origin—whether that’s the point of waste removal or access to water, and the system across the city that’s required to put that in place—and how that then relates to groundwater, soil, slope, the earth, topography, landscape, environment. All those things are connected.

You may have a small expression for a pump house or a single toilet within a public square. The design of that structure has been considered very carefully in terms of the language of the design, the setting, the image. But it’s just the tip of the iceberg, as you begin to trace the implications of that system.

Those issues of being able to jump scale, to address circularity in a contemporary condition with the climate challenges that we’re now facing, and overlaying that with the sensorial, intimate process and rituals around cleansing the body, waste removal, urination—those simple things that we do every day and take for granted. How do we think of those moments within the architectural or landscape or urban design project?

A piece that the students are reading right now, “In Praise of Shadows” (1933) by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, points toward the care and craft that goes into Japanese toilets, so as not to over-illuminate or over-expose. It allows for nuance. A shadow is something that, perhaps, we want to capture. It’s part of the human experience. It also hints at a sensibility about something other than purity or purification—something much richer.