A Moratorium on New Construction?

“Yet what we need is a voluntary cessation, a conscious and fully consensual interruption. Without which there will be no tomorrow.”1

The concept of sustainable construction does not hold meaning any longer. Real sustainability is an impossible endeavor and a delusion in the present modus operandi of global construction. From land consumption to material use, building is a destructive process: urbanization devours hectares of unbuilt land every year, and the construction industry relies intensively on resource extraction.2 Through mining, manufacturing, and building, the energy used in construction impacts the planet at a tectonic scale. Water bodies, ecosystems, topography, geology, climate, food systems, labor conditions, humans, and nonhumans everywhere are destroyed or damaged to propel voracious global supply chains.

The end of the world has been ongoing for many. From the tons of toxic bauxite residue stored in unstable pools in Hungary to the devastated social landscapes surrounding the coltan mines of Chile, this damage is a prerequisite of designed spaces, affecting all non-constructed surfaces—from forest to farmland.3 Despite loud calls to reexamine our faulty growth model, the expansionist global enterprise of land and resource exhaustion fueled by both construction and real estate development goes on relentlessly.4

Stop Building?

The call for a moratorium on new construction emerges from these global urgencies and from the palpable lack of action on the side of the building industry and planning disciplines beyond flaccid corporate strategies (green labeling, carbon compensation, material reinvention, and LEED, for example). Devised to cover up ongoing devastation, construction’s greenwashing of its toll on the environment is deployed in full force. Little is done to curb the damage done through commodified and speculative real estate development and construction schemes. Moreover, global material use is expected to rebound with post-pandemic economic policies and to double by 2060; a third of this rise is attributable to construction materials.

And this is but a fraction of what ultimately makes up the built environment. The transformation of raw resources into exploitable architectural elements (aggregates to concrete; sand and silica to glass; petroleum to insulation foam) not only necessitates the combustion of fossil fuel at every turn, but also relies on a host of facilitating technologies. Automated mining systems and computer-aided drawing software, for example, steer an increase in the extraction of critical minerals including aluminum, cobalt, copper, graphite, lithium, manganese, nickel, platinum, tin, titanium, tungsten, and zinc, among others.

The front lines of extraction are moving in all directions, and rapid devastation is ongoing. Paradoxically described as unavoidably necessary in order to transition to less carbon-intensive lifestyles in selected parts of the planet, this commodity shift toward rare materials suggests that sustainable oil rigs and e-Caterpillars will be undertaking the greener enterprise of destruction we design.

Against the propagandizing of ecological concerns both for eco-fascist agendas and as a business driver of technofixes, a moratorium on new construction calls for a drastic change to building protocols while seeking to articulate a radical thinking framework to work out alternatives.

House Everyone

Because housing is a human right and the mandate of the design disciplines, our fields stand at the difficult threshold between housing provision and devastation: How does one navigate the need for housing as well as the destructive practice of its construction? According to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) census of 2021, the median size of new single-family homes was 2,273 square feet, compared to 1,500 square feet in the 1960s, despite the shrinking of the median household size, down from 3.29 in the 1960s to 2.52 persons today.5 This trend sees more land, more materials, more appliances, and more infrastructures directed toward larger homes built to host fewer people, with debt at the core of its financing. In a talk at the GSD in February 2022, HUD secretary Marcia L. Fudge said that the days when one can have a plot to build a house were numbered—despite her lecture being titled “Building the World We Want to See.”6

If we jettison the maxim that the solution to the housing crisis is to build, myriad other possibilities come into view: decent minimum living wages, just protocols to housing access, rent control, zoning reforms, purchase of private property to provide public housing, fostering of collective ownership and forms of cohabitation, and alternative value generation schemes. These solutions allow us to move beyond the struggles and dichotomies that plague the debate: renting vs. ownership, YIMBYs vs. NIMBYs, nature vs. humans, and housing crisis mitigation vs. zero net emission, among others.

If new construction were to stop completely, even for a short while, the current built stock—buildings, infrastructure, materials—would have to be reassessed, and the productive and reproductive labor that goes into it necessarily would be revalued. Varying widely from well-paid skilled workers to exploited manual laborers, the labor force involved in construction remains mainly unautomated—and overlooked. We could anticipate the emergence of new societal and ecological values and a reevaluation of the labor involved in caring for buildings, from surveying the existing stock to engaging in reparative works to acts of daily upkeep.7

The effort ahead is immense; a different way of designing the world emerges, one that demands a careful assessment of present and vacant inventory, strong policies on occupancy and against demolition, anti-vacancy measures, densification plans, maintenance protocols, end-of-life etiquette for materials, and overall upgrading tactics. These will all need to be imagined, formulated, planned, and implemented—according to the needs of the context.

Who Is to Say Build or not Build?

At the same time, a moratorium’s global validity must be interrogated. The geography of harmful extraction and the political economy of construction are mirrored in today’s neocolonial modes of extraction capitalism, with gendered and racialized populations most affected. Assuming that the bauxite extracted in Guinea ends up on the facades of pencil towers in New York, shouldn’t a moratorium be limited to new construction where a consolidated stock already exists? Indeed, the integrity of the sustainability narrative is belied by the extent to which environmental laws have been successfully weaponized and how unpersuasive frugality arguments continue to be.

As Peter Marcuse argues, “the promotion of ‘sustainability’ may simply encourage the sustaining of the unjust status quo and how the attempt to suggest that everyone has common interests in ‘sustainable urban development’ masks very real conflicts of interest.”8 Achille Mbembe spells it out: “In Africa especially, but in many places in the Global South, energy-intensive extraction, agricultural expansion, predatory sales of land, and destruction of forests will continue unabated.”9 Thus, with overbuilding and resource consumption on one side and lack of housing and material extraction on the other, a new construction moratorium could be restricted to extractive built nations and adopted by countries incrementally along GDP lines.

Upon closer inspection, the need for nuance emerges. In Cairo, there are 12 million vacant units, high vacancy rates grounded in locally specific conditions such as questionable rent control laws, proactive suburban development state programs, and a lack of trust in banking institutions.10 In Costa Rica, the bulk of new construction consists of coastal residential units aimed at tourists or expatriates, fueling socio-environmental issues of displacement and degradation.11 In South Africa, the demolition of scarce public housing to make way for market-rate units shows the limitation of the construction-as-solution storyline.12

Nevertheless, building more is heralded everywhere as the sole answer, a debatable leitmotif served up from the Bay Area to Mumbai that conceals the reality of the commodification of housing fueled by debt financing. Housing needs are not the question when home insecurity is such an acute problem for many, and when it is true that crucial infrastructures are lacking in some regions.13 Thus, construction is not to be condemned outright when there are such vast disparities in what different countries can provide. But while contextual complexities require a deeper investigation into where and what is constructed and what should not be built, a moratorium on new construction challenges the incapacity of the sector to envision alternative large-scale housing provision schemes beyond building new.

Beyond GDPs and other faulty measurements, beyond moral confines and neo-Malthusian indictments, how are we to grapple with sustainability as a contested concept, legacies of degrowth theory, green capitalism, and problematic CO2 reduction policies becoming the stuff of riots?14 How many of the thousands of new housing units built every year everywhere are accessible to those who need them most? How can we optimize and maximize our existing stock before extracting new materials? How do the design disciplines face their complicit role in environmental degradation, social injustice, and climate crisis, and challenge the current system of global construction?

Imagining Possibilities

The following vignettes play out in various locations to answer some of these interrogations. Drawing from A Moratorium on New Construction, an option studio that took place at the GSD in spring 2022, these ideas point to what must stop and what needs to change, from India to the United States. In contemplating redistributive modes of ownership and communing and questioning the standard claim of building right, predatory real estate practices, high-tech-heavy solutions, and the assumption that architects must build anew rather than practice methods of repair and prolonging, a vision for a material future relying on our current built stock emerges.

In Mumbai, a city where affordable housing is in high demand, the ongoing demise of chawls—collective units built in the 1930s for mill workers, and now home to active but modest communities—epitomizes the rapid destruction of affordable housing at the hands of the state and the private sector. High-rises for wealthier owners replace the chawls, and the tenants are displaced. Devashree Shah (MArch ’22) argues for a moratorium on the demolition of chawls and all subsequent new construction. But because aging chawls’ structures require upkeep, Shah proposes a post-moratorium design strategy that envisions physical and social repair as a unified design task.

From maintenance protocols (cleaning, clearing trash, painting, and re-plastering), to reparative works (replacing broken shingles, sistering, straightening structures), to strategic interventions (co-living arrangements, shared amenities), to additions aimed at increasing social capital (community kitchens, daycare centers), to strengthening neighborhood networks (pooling capital, sharing facilities), the design of an entire repair strategy at every scale advocates for a value shift, one that privileges care labor above newness. Primarily undertaken by gendered and ostracized populations, upkeep work is considered belittling to many. Shah’s project challenges this perception through a socio-spatial tandem design by illuminating the crucial relevance of repair work both for buildings and communities—in a context where new construction is halted.

On the shores of the Yucatán Peninsula, Tulum is the latest Instagrammable ecotourism destination, with its pristine beaches overlooking the Caribbean Sea, which already is dotted with so-called eco-resorts and sustainable Airbnbs. Tourism growth is highly contested by local communities who oppose the construction of a high-speed Mayan Train aimed at ushering in more visitors. Indigenous voices have pointed to the harm caused to the area’s fragile ecosystem by constant growth within their economies. Turning these calls into a radical design brief, Gerardo Corona Guerrero (MAUD ’23) designs the gradual recess of tourism activity in Tulum.

The project disputes the success story of ecotourism and imposes as a first step a moratorium on tourism-oriented infrastructure. Considering that the “reconstruction of nature” is an equivocal concept bordering on eco-fascism, the project embarks instead on an incremental approach, phasing measures across a time span of 70 years, from reparative ecologies to deconstruction and material reuse. It articulates a decolonial understanding of degrowth toward a negotiated human stewardship of the land.

Going against the grain, Aziz Alshayeb (MAUD ’23) proposes a critique of the current trend of demolishing highways. He exposes a national agenda of hardcore gentrification and CO2-heavy development operating under the auspices of post-oil mobility and community betterment. In this context, the project proposes a moratorium on the demolition of Highway I-45 in Houston and puts forward a counternarrative to highway demolition that is based on Sara Ahmed’s concept of “complaint as resistance.”15

Taking community grievance as mandate, the project seeks to listen to all—from anyone who has registered a complaint, and from children to bees—to articulate an alternative program to the kind of solutionism that currently plagues design. With tools including legal frameworks and ecological measures, the project pushes against the evils of urbanization, including environmental degradation and gentrification and their manifold consequences. What emerges is a future of peaceful cohabitation between nonhumans, humans, and our obsolete infrastructures.

Starting from the perspective that the single-family home is an unsustainable, energy-intensive housing type that is itself fundamentally grounded in colonization, Bailey Morgan Brown (MArch ’22, MDes ’22), a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, proposes a moratorium on suburban sprawl for Edmond, Oklahoma, a site she describes as being paradigmatic of settler-colonialism. She argues that the single-family house exemplifies the combined burden of legal, economic, environmental, social, and environmental pressures, in the form of mortgage financing, lawn care, air conditioning, car infrastructure, normativity, materialism, and low occupancy rates, among others.

Going further, Brown develops a protocol for establishing a sovereign suburban space, articulating a plan for how “land back” would actually play out. Her plan unfolds into a multilayered strategy that includes a land transfer of “unassigned lands” to a Tribal Cooperative Council; a mandate against the displacement of existing residents; the termination of property lines and of zoning and the creation of new land use definitions; and the development of ambiguous, contested, fluid, and temporal spaces for energy production, medicinal vegetation, nonhumans, crop production, and new models for taxation.

These few examples speak of the incredible potential of what design can do if new construction is not an option—the potential to confront the built environment’s past, present, and future and to engage with existing building stock to question the current economic model of development and to move forward toward a better industry. Pausing construction problematizes the narrative of progress and techno-positivism that propel capitalist societies as well as the mandates for their design. Buttressed by an imperative for boundless economic growth proffered by postcolonial powers, those mandates sell “a better life for all humanity—a mentality that continues to structure global asymmetries,” as articulated by Anna Tsing.16

Nubian architect and decolonial scholar Menna Agha frames the call to “stop building to start constructing” as a prerequisite to setting off the reconstruction and rehabilitation of the built environments of the racialized, gendered populations bearing the brunt of ecological and social devastation.17 A pause would also allow the design professions to pivot toward resource stewardship, to remodel what we do and deploy design’s organizational capacity to (begin to) think about new forms of emancipated practice, to engage in remedial work, and to establish the care of the living as our sole priority.18 Somewhere between a thought-experiment and a call for action, a moratorium on new construction is a leap of faith to envision a less extractive future, made of what we have. It’s about building less, building with what exists, and caring for it.

Charlotte Malterre-Barthes is an architect, urban designer, and Assistant Professor of Architectural and Urban Design at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL). Most recently, she was Assistant Professor of Urban Design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where she taught studios and seminars and, in 2021, launched the initiative A Global Moratorium on New Construction, which interrogates current protocols of development and urges deep reform of the planning disciplines to address earth’s climate and social emergencies.

1 Achille Mbembe and Carolyn Shread, “The Universal Right to Breathe,” Critical Inquiry 47, no. S2 (Winter 2021): S58-S62, https://doi.org/10.1086/711437.

2 See David Harvey, Explanation in Geography (Jaipur, India: Rawat Publications, 2015).

3 See Martin Arboleda, Planetary Mine: Territories of Extraction under Late Capitalism (Brooklyn: Verso Books, 2020).

4 “A Global Moratorium on New Construction” was an initiative started in April 2021 and undertaken with B+, in the form of four roundtables that generated a wealth of ideas instrumental to articulate this work. I would like to thank for their generous inputs: Cynthia Deng & Elif Erez, Noboru Kawagishi, Omar Nagati & Beth Stryker, Sarah Nichols, and Ilze Wolff (1st roundtable, April 2021); Menna Agha, Sarah Barth, Leon Beck, Silvia Gioberti, and Kerstin Müller (2nd roundtable, June 2021); Connor Cook, Rhiarna Dhaliwal, Elisa Giuliano, Luke Jones, Artem Nikitin, Davide Tagliabue, and Sofia Pia Belenky, (Residents of V—A—C Zattere with Space Caviar (3rd roundtable, July 2021); Manuel Ehlers, Saskia Hebert, Tobias Hönig & Andrijana Ivanda, Sabine Oberhuber, Deane Simpson, and Ramona Pop (4th roundtable, August 2021); as well as Arno Brandlhuber, Olaf Grawert, Angelika Hinterbrandner, Roberta Jurčić, Gregor Zorzi, and Rahul Mehrotra for supporting this experiment.

5 Unites States Census Bureau, “Highlights of Annual 2020 Characteristics of New Housing,” Census.org (2020), https://www.census.gov/construction/chars/highlights.html .

6 Marcia L. Fudge, “Building the World We Want to See: What Do We Want Our Legacy to Be?,” in John T. Dunlop Lecture (Harvard University Graduate School of Design: 2022).

7 Thanks to Sarah Nichols for articulating this idea in the frame of the first roundtable, “Stop Building?” in April 2021 at the Harvard GSD.

8 Peter Marcuse, “Sustainability Is Not Enough,” Environment and Urbanization 10, no. 2 (October 1998).

9 Mbembe and Shread, “The Universal Right to Breathe.”

10 Yahia Shawkat and Mennatullah Hendawy, “Myths and Facts of Urban Planning in Egypt,” The Built Environment Observatory (2016). Omar Nagati and Beth Stryker in Stop Building? A Global Moratorium on New Construction, eds. Charlotte Malterre-Barthes and B+ (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Design, 2021).

11 See Andreas Neef, Tourism, Land Grabs and Displacement: The Darker Side of the Feel-Good Industry (London: Routledge, 2021).

12 Ilze Wolff in Stop Building? A Global Moratorium on New Construction, eds. Charlotte Malterre-Barthes and B+ (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Design, 2021).

13 See Matthew Desmond, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (New York: Crown/Archetype, 2016).

14 Marcuse, “Sustainability Is Not Enough.”

15 See Sara Ahmed, Complaint! (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021).

16 Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015), 23.

17 Menna Agha in Pivoting Practices. A Global Moratorium on New Construction, eds. Charlotte Malterre-Barthes and Roberta Jurčić (Zurich: Swiss Institute of Technology, 2021).

18 Elif Erez and Cynthia Deng, “Care Agency: A 10-Year Choreography of Architectural Repair” (Harvard Graduate School of Design, 2021).

Danielle Allen on Government Design, the Constitution, and the Crisis of Representation

The following is Danielle Allen’s 2022 Class Day Lecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, which she delivered on May 25, 2022.

It is such a pleasure and honor to be with all of you today. It’s a miracle day: a miracle to celebrate the accomplishments we’ve just been hearing about, the miracle of the beautiful afternoon you’ve delivered to us, and the miracle of the possibility you all present. You’ve brought so much light and joy as we’ve learned about your work tackling climate change, affordable housing, machine learning. Resilience was a theme we heard again, and again, and again. You are clearly the class of resilience. And, boy, is that something we need right now.

Dean Whiting started out by asking us to remember the moment we’re in. And it is a hard moment. You all know that, and I don’t have to tell you. So, it is a responsibility for all of us to do the work of holding light and dark together, as Ralph Ellison, one of my favorite authors, once wrote. And you, as I said, have brought us so much light. It’s what we need in this world right now. I’m going to spend some time with you this afternoon proposing that above all, we need designers to take on the problems that confront us.

The gifts you have as designers are what the rest of us need to help us navigate the challenges that we face. I’m going to put to you the proposition that many of the problems in this country, specifically, are design problems. And therefore, I have come to the right place this afternoon in seeking out solutions. The problems in this country are not parochial, however. They are questions, ultimately, about human empowerment and what’s possible on our globe. You are a broad class from all over the globe.

I believe that the problems we’re wrestling with here in this country can be informative for the efforts of human beings everywhere to build that path to connection and empowerment. So, I am going to dwell on the US this afternoon. But in that spirit of seeking to open up a horizon of possibility for all of us, I want to say a little bit more about myself. I’m a philosopher and an ethicist, trying to be a politician in a certain kind of way. I’m a kid who grew up in Southern California in the ’70s, part of a huge family. My dad grew up in northern Florida with 11 brothers and sisters. Half of them sought to escape the Jim Crow South by moving to Southern California.

So we were a huge cousinage. And we were all incredibly politically committed. Almost as if with mother’s milk, we took in the lesson from W.E.B. Du Bois about democracy, about the ballot. Du Bois said, “The power of the ballot we need in sheer defense, else what shall save us from a second slavery?” Democracy is that fundamental, that much at the core of what it takes for communities to have a path to empowerment. We all dug in, and fought, and believed, but across the entirety of the political spectrum.

I remember the year that my aunt was on the ballot for Congress in the Bay Area for the far left Peace and Freedom Party. It was the same year my dad was running for Senate from Southern California as a Reagan conservative. So, boy, those were some dinner table conversations. They always agreed on the what. The what was empowerment for communities, so that those communities could build the security they need to thrive.

The disagreement was on the how. My dad—skinny, with smoke from his pipe curling around his head and bald at 20, poor guy—was making the case for market freedoms and libertarian choice as the way to empowerment. And my aunt—Mack truck, big belly laugh—was making the case for investment in productivity across all the sectors of our society and community. They went at it; but never breaking the bonds of love, never breaking the bonds of mutual respect, that commitment to each other as human beings.

That’s the lesson I took from my childhood about what democracy can give. That space for contests, to have those hard fights, and to try to find that path to empowerment for everybody. I grew up having a sense of our country and our world as being a mix of light and dark. I could see the accomplishments of the country. I could see the opportunity it delivered. I could see the potential. I could see our failings and our errors for sure.

Over the course of my lifetime, we have lived through some extraordinary things in this country. A half century of time. In that time, we’ve had what I call “the great pulling apart.” There’s a massive increase in income and wealth inequality. To the point that we’re at the same place that we were in 1929 before the Great Depression. It is the period of time where we have seen the massive rise in incarceration that has trapped communities of color, and some of the worst things imaginable for any young person coming into the world on our planet. It is also a period of time where we have seen polarization and the acceleration of climate crisis. And now, this remarkable thing we’re living through, where we’ve moved from a period of globalization to a period of deglobalization. A period of great pulling apart. My own family has experienced that pulling apart. Some of us got lifted up on elevators of opportunity to positions of the greatest privilege the world has to offer.

There is no greater privilege than being a tenured professor at Harvard University. Jeff Bezos could forget it. Billionaires can forget it. I mean it: there is no greater position of privilege. And those of us who have the chance to be here owe the world so much. But, at the same time, some of my cousins have gotten trapped and pulled into the worst the world has to offer. I’ve lost a younger cousin by the same name, Danielle, to substance use, and opioid substance disorder. I have lost another cousin, not dead, but broken by a police beating in a case of mistaken identity. The person they were looking for shouldn’t have been beaten like that, and my cousin definitely shouldn’t have been beaten like that. But for me, the real turning point moment—the moment where I went from having a mixed light and dark sense of our world to having a pretty dark sense of our world—came in 2009, when I lost my baby cousin, my youngest cousin, Michael.

Michael was probably the first baby I ever held when he was born in 1979. I was a lonely kid being bullied on the school playground that year. And then my aunt delivered a ready-made new best friend. He was a beautiful kid, full of curiosity, with a bright smile and a lively mind. He wanted to grow up, and travel the world, and learn French. Instead of that, in 1995, when I was a couple of years out of college, he was arrested in Southern California on a first arrest for an attempted carjacking.

This is a terrible thing to have done. It was also a time in California where punishment was at its most intense. On that first arrest, at the age of 15, Michael was sentenced to 12 years and 8 months. When he got out after 12 years, I was what I call “cousin on duty.” I tried to put the pieces back together again by helping with housing, and school, and jobs. Michael had two years out, two years of freedom—that treasure—when he was shot and killed by somebody he had met while he was in prison.

It’s a hard story to hear—I know that. Especially on a miracle day like today. And it’s a hard story to tell. But I tell that story because that was the point for me, that turning point moment, where I started to dig into the question of how in this country, we could steer our institutions to achieve the kinds of reforms that would open up opportunity for communities of all kinds, put a foundation for flourishing back underneath everybody. And the truth is, I got more and more frustrated as our politics also got more and more complicated, and more and more polarized, and more and more difficult.

So now I come to that design problem that I promised I was going to share with you. It’s the reason we need you and your great gifts at this hard moment in time. Why is it exactly that things are so crazy, so complicated, so messy in this country right now? The short answer is that Facebook broke democracy. They didn’t mean to. It was definitely an accident. But they definitely did.

Now, I want to explain that. What do I mean exactly? The fact of the matter is that when this country was founded, it was an experiment in design. The problem that the country faced in the 1780s was that they could not get a functioning banking system. They could not pass a budget in Congress. They did not have a quorum in Congress. They could not make decisions. It was a broken thing, a set of machinery that didn’t work.

Out of that moment and problem came the Constitutional Convention. It was a design solution to the problem of a community of people who could not actually get anything done together. And in that moment when they designed that Constitution, they had all kinds of problems of tribalism, and factionalism, and division—just as we do now. This was, in fact, one of their greatest concerns. So, the Constitution was literally a design solution to the problem of faction, and division, and polarization.

Let’s dig into the nature of that design and how it was supposed to solve that problem. The answer, the solution, the design is described in detail by James Madison, one of the authors of the Constitution, in an essay called “Federalist Paper Number 10.” The Federalist Papers were a series of essays published in the newspaper to defend the new Constitution. And in that 10th essay, Madison takes the time to explain how this design is supposed to address the problem of faction.

We teach this essay to undergrads in a variety of courses. And we typically teach the design solution as one where a broad republic was supposed to solve the problem. But when we teach this paper, we usually just focus on the word republic. The basic argument made is that a republic is a structure of government with representatives. People get elected to serve. And it’s the job of the representatives to synthesize, and moderate, and deliberate, and bring together to find a solution for hard political problems.

We forget to teach the part of the design solution that is captured by the word broad. And that word was actually a proxy word for geographic dispersal. Madison was very clear that one of the things he expected to see in a country that was spread out across a continent separated by rivers and mountains was that people with extreme views would not be able to find each other. This was a premise.

The idea was that because of geographic dispersal, in order to get your views into the public sphere, you would have to go through a representative. Geography was a forcing factor to make a system of representative government work. But that part just doesn’t exist anymore. An actual premise undergirding the design of the Constitution was knocked out by social media. That’s what I mean when I say that Facebook broke democracy.

What that means is that we have a very significant design problem facing us right now in any country that wants to organize a structure of self-government. We have a crisis of representation. And I want to just drive home how impactful that crisis is by calling your attention to a funny feature of our political landscape in this country. If you look at our national politics, we look exceptionally divided. We look like we are at each other’s throats all the time.

But if you change your attention, if you look elsewhere, if you look at state politics and ballot propositions, you see a different America. In Florida, a supermajority of people voted to re-enfranchise, to return the right to vote, to people who had completed their felony conviction. By supermajority, I mean more than two-thirds of the electorate, so Republicans as well as Democrats. In Mississippi, in 2020, more than 70 percent of the people voted in a new state flag, getting rid of the old emblems of the Confederacy, and adding forward-facing symbols.

Here in Massachusetts, 75 percent of us voted for the Right to Repair ballot proposition, which gives small auto dealers and auto shops access to the data in cars, giving them the chance to compete against big auto manufacturers. Three different states, three very different contexts, and American people standing up for inclusion and fairness, sticking up for the person getting the short end of the stick. You wouldn’t know that from our national politics.

That’s where the crisis of representation comes in. There’s a disconnection between our representatives and what’s actually happening in terms of what people are willing to do in our states at a more local level. That’s the design problem that we have to address. There are solutions out there in the political landscape. For example, ranked-choice voting is a good one. It requires candidates to try to build actual majority coalitions, instead of just carving off minority portions of the vote that lets people with more extreme views get through. That’s a political solution.

And we need those. But I believe we also need a whole host of other solutions. I was hearing you talk about some of them, listening to those prizes listed. We need public spaces where people can see themselves together and with one another again. The work on affordable housing is critical, because at the moment, we are letting our society just segment into class-separated ways of living and being. And we will not find our way back to solutions with those divisions.

Some of you have been working on Big Tech and machine learning. And we have to figure out how to design these tools—which are now the infrastructure of our information ecosystem—in ways that are actually good for us. But above all, my experience of working with designers is that you believe in the power of communities to articulate their needs and to participate in the design process.

I think that is a skill you’ve been taught throughout your classes during your time here. It’s not taught everywhere. Lots of times, people and institutions will try to deliver solutions in a top-down way. And if we are going to design our way out of the problems that we have right now, we really need your skills. We need you to lead us in engaging big, cross-cutting communities in participatory processes to get us to a goal that supports a healthy society. So, it is a hard time.

I just told you the story in my own life of the point at which for me dark started to outstrip light. But I have to admit, I’m a commencement junkie. I love commencements because this is where hope is. And again, I heard it with such power, and force, and clarity in the descriptions of your work. So it is an honor to be with you and with your work. We will be both resilient and OK. So thank you.

–––

Danielle Allen is a professor of public policy, politics, and ethics at Harvard University, and James Bryant Conant University Professor, one of Harvard’s highest honors. She is also a seasoned nonprofit leader, democracy advocate, national voice on pandemic response, distinguished author, and mom. Danielle’s work to make the world better for young people has taken her from teaching college and leading a $60 million university division to driving change at the helm of a $6 billion foundation, writing for the Washington Post, advocating for cannabis legalization, democracy reform, and civic education, and most recently, to running for governor of Massachusetts. During the height of COVID in 2020, Danielle’s leadership in rallying coalitions and building solutions resulted in the country’s first-ever Roadmap to Pandemic Resilience; her policies were adopted in federal legislation and a Biden executive order. Danielle made history as the first Black woman ever to run for statewide office in Massachusetts. She continues to advocate for democracy reform to create greater voice and access in our democracy, and drive progress towards a new social contract that serves and includes us all.

The Power of a Worldwide Design Community

During an unprecedented time, the Harvard GSD Alumni Council created Design Impact, a leadership series that emphasized design as a tool for transformative change and healing.

Design’s power has always been most potent when its practitioners can come together. In the early days of the pandemic, though, the world was folding into small, quarantined boundaries. That moment revealed two things to the Harvard Graduate School of Design Alumni Council: we need practical, actionable design solutions to solve our global challenges now more than ever, and we need to do it together.

Out of that spirit, Design Impact

was born. This global design leadership speaker series brought together outstanding rosters of global leaders to share their work and vision, challenging the worldwide design community to use the field and its knowledge base as tools for transformative change and healing.

“In a time that is requiring us to meet challenges that are unprecedented, our goal was to create communities of leadership where people can lead with who they are, from where they are, with what they can,” said Ana Pinto da Silva (MDes ’05), the Design Impact co-chair and CEO of 2G3R Inc., which designs homes and communities for people of all ages and abilities. “We want to foster and support a community of leaders—as many as we can. That’s what will help at this point.”

The reach and diversity of the GSD alumni community—who they are, where they are, and what they can do—translated to a wide range of highly relevant topics with engaging speakers and discussions. Members of the Alumni Council settled on what they saw as the most urgent global issues: equity, homelessness, climate change, community and innovation, health, and resilience.

Design Impact also became the perfect platform to allow us to partner with many other Harvard Alumni Councils or associations and professional organizations. It is one step toward creating One Harvard.

Peter Coombe (MArch ’88), Alumni Council Chair

“We realized early on that we could leverage virtual meetings to engage far more members of the design community than we had ever had in the past,” said Alumni Council Chair Peter Coombe (MArch ’88). “Over the course of the five volumes of Design Impact, we registered nearly 10,000 participants from more than 100 countries. Design Impact also became the perfect platform to allow us to partner with many other Harvard Alumni Councils or associations and professional organizations. It is one step toward creating One Harvard.”

“We were bold and ambitious,” said Sameh Wahba (MUP ’97, PhD ’02, KSGEE ’13), who serves at The World Bank. “We were sending the message to the alumni that during a pandemic, the worst wave of racism, the crisis of climate change—design has a role to play.”

As Pinto da Silva put it, Design Impact was a labor of love. Numerous GSD Alumni Council members volunteered their time, partnering with the school and its students to create a series that was free and open to all. The events were volunteer-driven, and speakers appeared at no cost, as they were motivated by the importance of this series and the topics it covered.

Jaya Kader’s (MArch ’88) sessions focused on climate change , with an emphasis on radical sustainability and regeneration . Those aspects dovetailed with her work as founder and principal of KZ Architecture, a Miami-based full services design studio committed to design excellence and sustainable building practices. Hundreds of people tuned in to the panel on regenerative economics and language, which featured Indigenous leaders.

“It was transformational,” Kader said. “With regenerative design, you look at whole systems. You rethink everything that we’re conditioned to think and look at actualized potential.

“The power of design is to envision and create new worlds. That’s what we do,” she added. “We need the right brain, the creativity, the creators, the artists, the designers to come up with solutions.”

GSD students also had an opportunity to moderate and curate the sessions, as Naksha Satish (MAUD ’22) did for an event centered on South Asia

. She happened upon the event by chance: she filled out a Google form expressing her interest in participating, which she saw as reflecting the Design Impact theme of democracy in design.

“It was a great way to see the GSD family that exists beyond the school. After being associated with the Design Impact group for more than a year, it really feels like a family,” Satish said. “It was also a good way to segue from the academic perspective to look at the same topics from the practice perspective and engage with current practitioners who had a similar academic trajectory. You can understand the broad ways in which you can think of yourself as a practitioner, and you connect with the fraternity now in different ways.”

The intergenerational, transdisciplinary connections between alumni and students quickly grew into Pinto da Silva’s most treasured moments of Design Impact. “When someone in their seventies is working with someone in their early twenties, that’s powerful. You need to step aside. The stuff that comes out is so important,” she said. “The more we partner, the more we can expand our reach and be in service to our different constituencies.”

All in all, the series reached a combined audience of more than 3,000 with four virtual events

in FY21. The series culminated in September 2021 with a two-day virtual summit titled “Design Impact Vol. 5: Following the Sun: Design Futures at the Intersection of Health, Equity and Climate Change Virtual

.” The idea for this round-the-clock event, spanning time zones and reaching every corner of the GSD community, came from similar summits that Wahba had attended in his position as a global director at the World Bank. Through this summit, the final Design Impact transcended regional and national boundaries to unite the global community of practice.

Coming out of the events, 83 percent of attendees were able to identify actionable tools they could incorporate in their professional practice. That practical perspective resonated with John Friedman (MArch ’90) and his wife, Alice Kimm (MArch ’90), who curated sessions about homelessness. The couple are co-founders of John Friedman Alice Kimm Architects (JFAK), which they established in 1996 in Los Angeles based on a “common desire to create architectural environments that are simultaneously joyful, meaningful, and sustainable.”

“The GSD is shifting with the times and being less high-design and more globally focused on justice and equity,” Friedman said. “People in other countries are dealing with this stuff every day: trying to find clean water, basic shelter, dealing with incredible extremes of wealth and poverty. With Design Impact, there’s a lot of good info and sharing across cultures, which is really valuable.”

The Alumni Council is strategizing how to best share the volumes of information that came out of Design Impact and exploring how to strengthen this real-world bridge across disciplines, demographics, GSD Alumni, students, and the school. In the meantime, those who took part in Design Impact are celebrating how it brought the GSD community together in a challenging year—and provided avenues on how design can overcome those obstacles.

“This continues as a forum to express ideas for how we use design for transformation in the world,” Kader said. “The message that Design Impact brought will carry on for years to come.”

To learn more about Design Impact, click here

. Event recordings are available on the GSD’s YouTube Channel

.

Design Proposals for the Uncertain Future of American Infrastructure

As the world ground to a halt in the spring of 2020, with the COVID-19 pandemic shuttering shops, schools, subways, and offices, a street in Queens opened itself up as a new site of social infrastructure. [1] Located in Jackson Heights, one of the most congested neighborhoods in New York City with among the least green space per capita, a 26-block stretch of 34th Avenue was transformed into a 1.3-mile-long “vertical park” by the grassroots 34th Ave Open Streets Coalition. For 12 hours a day, every day, the street closed down to cars, permitting weary workers, solo-living seniors, and working-from-home parents and their children to stretch their legs, join in socially distanced exercise classes, swing by a community-led food pantry, or tend to a communal median garden that was—finally—their own.

Heralded as a visionary prototype for a more equitable and sustainable future city, the project also underscored the importance of civic space in an era marked by increasing privatization of the public realm. Reclaiming the street within a pandemic that both exposed and exacerbated the stark inequities of access to healthcare, community support, and green space across the United States framed the necessity of such spaces, in the words of sociologist Eric Klinenberg, as a matter of life or death. [2] In a keynote lecture recently delivered at the GSD , Klinenberg highlighted 34th Avenue as a success story within a larger domestic policy movement toward an expanded definition of infrastructure, in part fueled by the pandemic. “The pandemic forced us to hunker down and maintain physical distance,” says Klinenberg. “But we also developed newfound appreciation for gathering places that we had taken for granted. My hope is that we channel that into support for social infrastructure. We’re living through a unique moment, and we’re poised to make transformative investments in the physical systems that sustain us.”

Such an investment may begin through the Biden administration’s Build Back Better framework. Viewed as one of the most significant domestic policy agendas since the New Deal of the 1930s and the Great Society of the 1960s, Biden’s original $3 trillion BBB plan comprises two pieces of legislation: the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill, signed into law on November 15, and the $1.75 trillion Build Back Better (BBB) bill, which remains stalled after a firm rebuke from Senator Joe Manchin.

The infrastructure bill (also called the public works law) addresses what we typically think of as infrastructure, and offers the largest investment in the sector in over a decade. It includes funding for repairing and expanding roads, bridges, mass transit, and rail service, as well as upgrades to ports, electric grids, and water infrastructure. It casts a wide net across the country, including the replacement of lead pipes in Illinois, bridge repairs in Massachusetts, regional transit connections in Louisiana, and abandoned mine cleanup in Kentucky. In addition to bolstering material infrastructure, the bill hones in on the so-called “digital divide,” funneling $65 billion into expanding broadband access to rural and disadvantaged communities in the US.

The controversial BBB bill—focusing on what it terms “human infrastructure,” or social infrastructure—includes allocations of $150 billion for new affordable housing, $550 billion for climate-related policy and programs, $18 billion for universal pre-K, and $200 billion for childcare. For political reasons, however, many of these provisions will be absent from the bill, if it ever clears the senate. Both bills are the first pieces of federal legislation in over a decade to address the climate crisis and suggest solutions for mitigating the impact of global heating.

Across both bills, the idea of infrastructure expands to include social reform, digital telecommunications networks, climate justice, clean energy, and affordable housing. In addition to Klinenberg’s keynote, multiple studios and seminars at the GSD last term attempted to grapple with this multifaceted understanding of infrastructure. “That the Biden bill recognizes and supports social infrastructure, the economies of care, and reproductive labor, particularly at the household scale, is an exciting step for a country wherein everything has been relentlessly privatized,” says Malkit Shoshan, who taught “Reimagining Social Infrastructure and Collective Futures” in the fall. “By strengthening the household economy, stronger households can better interact with other households and create a commons. These issues should be essential to talking about the future of infrastructure—that it’s a matter of the values we preserve as a society.”

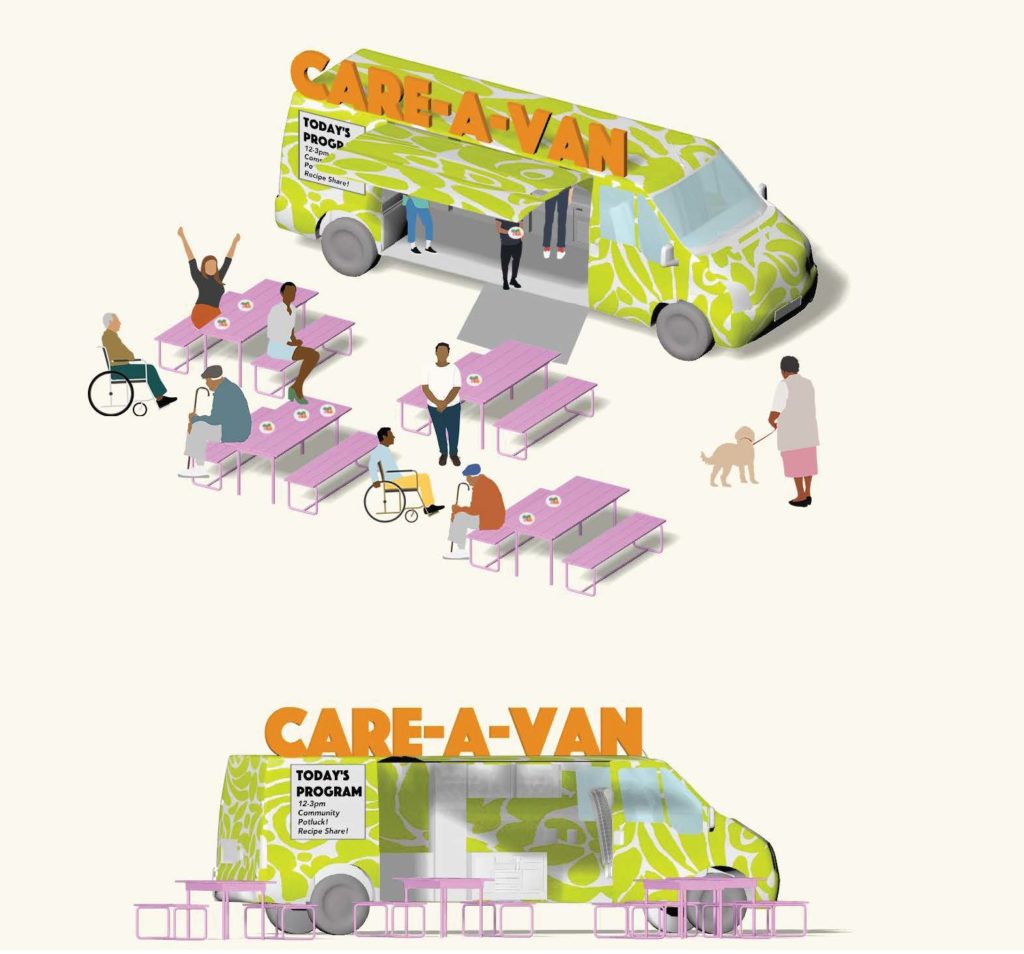

Shoshan framed her project-based seminar with key theories intersecting the social sciences, economics, feminist theory, and ecology, including those of economist Kate Raworth, author of Doughnut Economics, and philosopher Sylvia Federici, whose writings on reproductive labor have found new relevance during the pandemic. Students were asked to envision a more intersectional social infrastructure, where the well-being of mothers, caregivers, the elderly, and other marginalized groups, as well as precarious public services, were integrated into a collective future vision of a healthier planet. Among the projects to emerge from the seminar was a reimagining of the post office infrastructure, which is at risk of privatization, as well as a mobile “Care-a-Van” that revitalizes the lives of the elderly and reintegrates them into public spaces, generating new social networks. A “school for the future” sought to support an underserved public high school in East Boston, the largest in the area, in a neighborhood expected to be flattened by sea-level rise as early as 2050. In addition to providing climate infrastructure, the project proposed opening up the physical infrastructure to community use in after-school hours.

Ron Witte’s studio, “ROOM,” took a micro-scale lens to the question of what constitutes good social infrastructure, from the design perspective of the public interior. Utilizing a new reading room for the Central Boston Public Library as a case study, students were asked to envision alternative design protocols for indoor institutional spaces in an era where the role of such spaces is expanding as social infrastructure. Proposals varied widely, from reimagining the cultural status of the library to a “high-tech medium,” where visitors are given a window into the guts of archival space through a series of tubes transporting reading materials, to cracking the institution open like an egg, making its processes visible from the outside and expanding the internal boundaries of the building. “Architecture has been pushed to the side in this conversation around the future of infrastructure,” says Witte. “We’ve tended to focus on broad questions around social infrastructure, economies, and public spaces, but without architecture to prompt them into a new state, nothing will happen.”

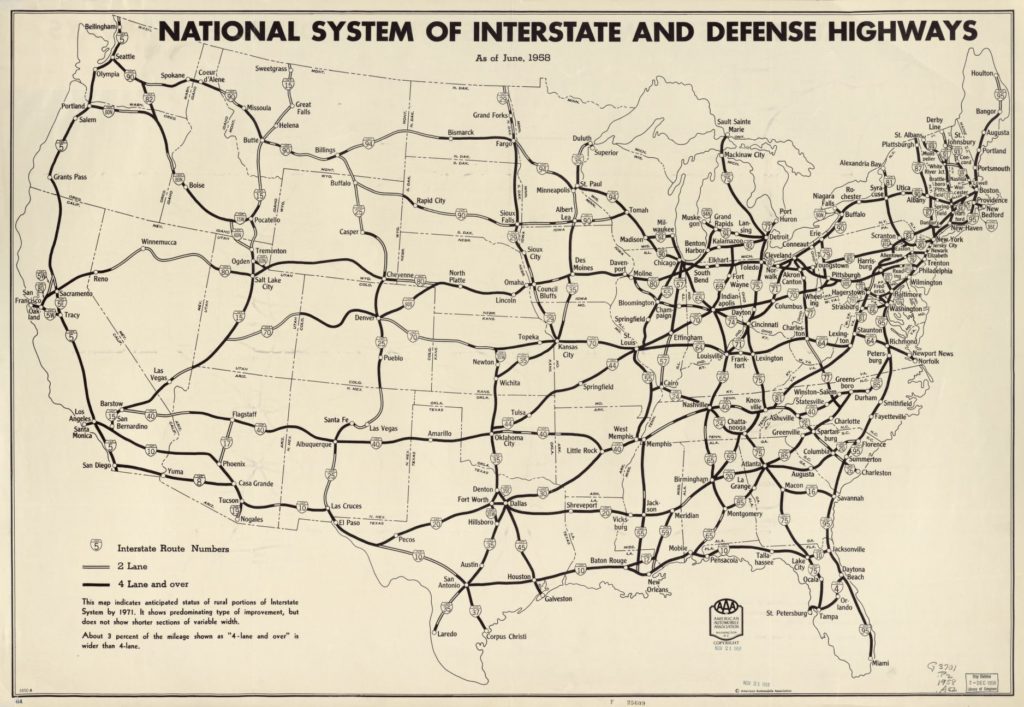

Additional federal efforts are necessary to ensure the Building Back Better framework’s climate resilience funds meet those who need it most. The new White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council is a step in the right direction, with 26 leaders from diverse communities appointed to judge applications for community-led climate infrastructure projects. [3] But there must also be increased support at the local level, to ensure these communities have no barriers to accessing funds and can realize these projects collaboratively. Responding to this condition, Dan D’Oca’s fall studio, “Highways Revisited,” was an exercise in reimagining the future of 10 cities and their surrounding highway systems. Each student was connected with a local activist or government official to envision an alternative use for that highway infrastructure while taking stock of its historical damage to disadvantaged communities.

Whittled down from a short list of 50 areas, the selected sites cover a wide range of topologies and racial and socioeconomic spectrums—they include El Paso, the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston, Detroit, Oakland, and New Orleans. “The idea was to find examples of cities where there was already a conversation about highway removal, but where things weren’t so settled,” explains D’Oca. “It was important for students to be able to think big and dream, but also have the guidance of a good liaison, and the tenability of a pitch process.”

“When you destroy a neighborhood you don’t just destroy homes, you destroy vehicles for amassing generational wealth.” – Dan D’Oca

With guidance from a lifelong resident of the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans (one of the oldest Black neighborhoods in the US, and the birthplace of jazz), one student transformed a stretch of I-10 that decimated the neighborhood into a powerful piece of community infrastructure, complete with public housing, green space, events programming, and an arts and music venue. (The White House has proposed removing the expressway altogether). For El Paso, another student nixed the freeway running along the US-Mexico border, restoring the original landscape of a green river valley and building a new neighborhood alongside it. In the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, a student worked with local liaisons to envision the removal of an eight-mile stretch of I-94, replacing it with a parkway, a rapid transit system, and new neighborhoods. The studio explored the emerging concept of “right to return,” currently piloted by the city of Santa Monica , which specifies Black communities displaced by mid-century urban renewal policies should be at the front of the line in new affordable housing markets. “When you destroy a neighborhood you don’t just destroy homes, you destroy vehicles for amassing generational wealth,” explains D’Oca. “So this idea of a ‘right of return’ being implemented by some local policymakers integrates the idea of infrastructure as an opportunity for reparations.”

Tom Oslund and Catherine Murray’s studio, “Harnessing the Future,” looked beyond the US to address the social, ecological, and economic entanglements of digital infrastructure in the small west Irish town of Asketon and the surrounding Shannon Estuary, where a new data center is slated for development. With a local environmental engineer as steward, students were tasked with reimagining the design of the data center to support the local economies and histories of Ireland, while adhering to the region’s strict conservationist protocols, and achieving carbon neutrality. One of the proposals utilized the energy of cow waste and Atlantic wind turbine production to fuel the data center. Another restricted its size and energy consumption to the amount of energy needed to churn Ireland’s signature domestic export, Kerrygold butter (and recycling the energy to do so). And the third proposal divvied up the area into wind energy–producing parcels of land owned by locals to sell back to data providers, flipping the power hierarchy between opportunistic data companies and residents. Oslund cites the main challenge with equivalent projects in the US as “a problem of too much land and too little restraint”—but is optimistic that an industry-led initiative for ecological design alternatives could catch on across the Atlantic. “The paradigm change that must happen is the responsibility of these companies,” he says. “Data centers have already surpassed airlines in carbon emissions, and there’s too much at stake. This studio was put in place to showcase more environmentally conscious design alternatives that support local economies and culture.”

As the future of the BBB remains uncertain, and the real work of the Infrastructure Bill lies ahead, it’s crucial that in expanding our definition of infrastructure, we take care not to divide it. A truly democratic approach to infrastructure acknowledges its constituency and responsibility across all sectors and publics: in other words, digital infrastructure must be social infrastructure; climate resilience infrastructure must also impart a civic value. Closing out his keynote lecture, Klinenberg gave a simple example for how this might be achieved: by revamping the design of a levee, which will be an increasingly common piece of infrastructure amid rising sea levels, to include a public park on top. What’s required is a crucial shift of perspective that enables new infrastructure. As Oslund says, it needs to “provide the same function, but allow for a different story.” There must be a design sensitivity on both a micro and macro scale to ensure it benefits those it has a particular duty to serve. The future of infrastructure requires a feminist design approach that centers marginalized groups; an equitable approach that incorporates reparations to communities who bore the damage wrought by earlier infrastructure projects; an ecological approach that acknowledges the stakes of the climate emergency; and the support of a public resource system that ensures the longevity of grassroots initiatives. Despite its warranted criticisms, the BBB framework offers a vital first step in this direction. Now, it’s up to designers and policymakers to get to work.

[1] In his book, Palaces for the People, sociologist Eric Klinenberg defines social infrastructure as a loose category of public places—parks, playgrounds, libraries, and town halls, as well as grocery stores, cafés, and barber shops—that are the spatial glue of a healthy society. Formal and informal, organized and happenstance, these are the hang-out spots where communities are made and people learn to look out for each other, particularly in times of crisis.

[2] Klinenberg’s acclaimed research on the “high resilience” areas of the 1995 Chicago heatwave pinpoints the significance of robust social infrastructure in contributing to low death tolls in otherwise demographically similar neighborhoods.

[3] Both bills intend to jumpstart the Justice40 Initiative ordered by Biden just days after taking office. It outlines that 40 percent of federal climate spending must reach underserved areas (formally defined as low income, rural, and/or communities of color), as a climate justice initiative. Despite these promises, critics argue this money will largely benefit middle-class, white communities .

Announcing the 2022 MICD Just City Mayoral Fellowship

The Just City Lab at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the Mayors’ Institute on City Design (MICD) are pleased to announce the launch of the 2022 MICD Just City Mayoral Fellowship, taking place in Spring 2022.

The 2022 MICD Just City Mayoral Fellowship will help mayors navigate a just and equitable recovery from the pandemic, providing actionable ideas for city leaders rising to meet this moment of change. Building on the inaugural 2020 Fellowship , this program will explore ways to create lasting, transformational impacts from new federal funding streams such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the American Rescue Plan Act. The Lab’s Just City Index will frame dynamic presentations and dialogues with experts in the fields of architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning, art activism, housing, and public policy. Over the semester-long program, mayors will identify how racial injustices manifest in the social, economic, and physical infrastructures of their cities and develop manifestos of action for their communities.

The 2022 MICD Just City Mayoral Fellows include Charleston, SC Mayor John J. Tecklenburg ; College Park, MD Mayor Patrick L. Wojahn ; Duluth, MN Mayor Emily Larson ; Madison, WI Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway ; Providence, RI Mayor Jorge O. Elorza; Richmond, VA Mayor Levar M. Stoney; Salisbury, MD Mayor Jacob R. Day ; and Youngstown, OH Mayor Jamael Tito Brown .

The Just City Lab is a design lab located within the GSD and led by architect and urban planner Toni L. Griffin. The Lab has developed nearly 10 years of publications, case studies, convening tools and exhibitions that examine how design and planning can have a positive impact of addressing the long-standing conditions of social and spatial injustice in cities. The Mayors’ Institute on City Design (MICD), the nation’s preeminent forum for mayors to address city design and development issues, is a leadership initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with the United States Conference of Mayors . Since 1986, MICD has helped transform communities through design by preparing mayors to be the chief urban designers of their cities.

“I’m delighted to see this powerful collaboration between the Just City Lab and the Mayors’ Institute on City Design continue,” says Sarah Whiting, dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture. “This year’s cohort of mayors come from many cities that are particularly interesting to our students as they consider their future plans. These are mostly middle-sized cities that are transforming quickly as a response to the skyrocketing costs of our nation’s largest urban centers. The Mayoral Fellowship is well-timed to help these eight mayors lead in terms of equity and opportunity. Our aspiration is that ‘just cities’ will become the standard for what we expect in this country, not the exception to what so many experience today.”

“Mayors have led our communities through a series of unrelenting challenges over the past two years. With new federal funding streams, we have a unique opportunity for once-in-a-generation change,” said Tom Cochran , CEO and executive director of the United States Conference of Mayors. “Mayors are now tasked with uniting their communities around real solutions and making transformational investments. The traditional MICD experience, with its candid, small-group format and access to national design experts, is so often transformative for mayors. There is no better model for empowering mayors to find solutions in our nation’s cities, and the United States Conference of Mayors is proud to partner with the Just City Lab to help guide mayors through this important chapter of American history.”

“Building on the National Endowment for the Arts’ vision to heal, unite, and lift up communities with compassion and creativity, we are proud and humbled to continue this important collaboration between MICD and the Just City Lab,” said Jennifer Hughes, NEA director of design and creative placemaking. “This program will take the transformative power of MICD, which illuminates the power of design to tackle complex problems, and apply it to the defining challenge of our time: ensuring equity and justice for everyone.”

On April 22, the 2022 Fellows will come together to discuss strategies for using planning and design interventions to address racial injustice in each of their cities at a GSD event hosted by Griffin. The program will be free and open to the public.

The Just City Lab and MICD are thrilled to continue this fellowship to help mayors shape more just cities. Learn more about the host organizations at www.micd.org and www.designforthejustcity.org .

Parts of this press release also appeared on the MICD website .

Faculty-led Stoss Landscape Urbanism tapped to develop Boston’s first Urban Forest Plan

Stoss Landscape Urbanism, the design studio founded by Chris Reed, has been selected to develop Boston’s first Urban Forest Plan in collaboration with forestry consultant Urban Canopy Works. The effort will establish a 20-year canopy protection plan for the city and address topics including ecology, design, policy, environmental injustice, and funding. In addition to his role as founding director at Stoss, Reed serves as professor in practice of landscape architecture and co-director of the Master of Landscape Architecture in Urban Design program at the Graduate School of Design. His colleague Amy Whitesides (MLA ’12), director of resiliency and research at Stoss and design critic in landscape architecture at the GSD, will lead the effort for the studio. “Our job is to fuel the project’s success by coordinating efforts between all the partners who each bring their own unique expertise,” explains Whitesides. “The ultimate goal is to maximize the health of Bostonians and their environment. We’re proud to work with the City of Boston on this shared commitment to Boston’s Urban Forest Plan.” The project will consist of scoping and assessing the existing state of Boston’s tree canopy while developing a plan to engage the community. Since tree removals on residential, private, and institutional properties have been the main contributors to canopy loss in the past five years, the Urban Forest Plan will also highlight policy tools to expand canopy on public streets and parks and control future loss on private property. The planning process will kick off in the spring of 2021 and will take approximately one year to complete. Boston Mayor Marty Walsh says that the Urban Forest Plan will “ensure our tree canopy in Boston is equitable, responsive to climate change and ensure the quality of life for all Bostonians.” He also emphasizes the importance of community input so that “residents in our neighborhoods have a central voice in this process.” Commissioner of Parks and Recreation Ryan Woods adds, “It’s no coincidence that many of the communities disproportionately impacted by poor air quality and the urban ‘heat island’ effect, also have inadequate tree cover. We’re excited to collaborate with these partners to find opportunities for growing tree canopy in the places that need it most.” Read more about the Urban Forest Plan on the City of Boston’s website and in World Landscape Architecture.Urban Planning alum Justin Rose on community organizing in Baltimore: “Often the people who hold the knowledge or insight that can unlock a creative solution are overlooked.”

Excerpted from the Harvard Gazette series, To Serve Better .

Whenever Justin Rose (MUP ’18) sits in a community meeting, he takes note of the people who aren’t speaking. They are generally the ones who haven’t yet been invited to offer their opinions — and they are the ones Rose wants to hear from most.

“Often the people who hold the knowledge or insight that can unlock a creative solution are overlooked,” said Rose, who works as a performance analyst in the Baltimore mayor’s office of Performance and Innovation. “I seek out those people and bring them into the process; their experiences are essential.”

That interest in engaging residents and finding ways to bring them into the conversation sits at the heart of the way Rose views his work. The North Carolina native spent time in Boston working as a community organizer with low-income and elderly populations, and the path to his current job began at the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative while studying at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

“There can be a big disconnect between policymakers, the decisions they make, and the lived experiences of the people who are most impacted by those decisions,” said Rose. Because of this, he spends his time in the community working to bridge that disconnect by helping residents track the efforts of city departments in their neighborhoods.

Rose emphasizes that his role is equal parts organizing and data analysis. Relationship building, both in the community and with his government colleagues, is what he points to as keys to success.

Often the people who hold the knowledge or insight that can unlock a creative solution are overlooked.

Rose’s Performance and Innovation team just launched CleanStat , a component of Mayor Jack Young’s “Clean It Up!” campaign to tackle the city’s persistent trash and litter problem. CleanStat takes the trove of data the city has and turns it into visual representations of targets and successes, and it allows residents to easily sort through that data to see progress in their own neighborhoods.

“The dashboard [we developed] has to serve multiple purposes: inform the public; help departments manage their business, and serve as a quality check,” Rose said. “We have so much [data] that can be used to communicate how, where, and why we deliver services.”

Something he appreciates about the people who serve in city government is their passion and commitment; they live the issues that they go to work each day to address, he noted.

It is a personal connection he not only admires but tries to emulate by getting out into the community, asking questions, and listening.

“With every data set I work with, I try to pop the hood and find out specifically how the data is generated and what the story behind it is,” he said. “Doing this, you get to the truth of the matter really quickly.”

As he continues working on the mayor’s ambitious agenda and the essential priorities of the community, Rose says his goal is to help city government slow down and recognize the knowledge that exists in the community as they work to implement change.

Justin Rose (MUP ’18) is using his skills as a community organizer and his experience working with complex data sets to help Baltimore solve their most pressing problems, all while preserving the city’s rich history.

Taking up social and spatial equity in New York

Design and the Just City, an exhibition curated by the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Toni L. Griffin and her Just City Lab at the GSD, arrives at the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Center for Architecture this month with fresh observations on social and spatial justice in New York. The exhibition debuted in the GSD’s Frances Loeb Library as part of the Spring 2018 exhibitions program. With a New York-focused twist, “Design and the Just City in NYC” is now on view at the AIA’s Center for Architecture through March 30, with a launch event on Thursday, January 10.

Like Griffin’s Just City Lab, Design and the Just City in NYC interrogates how design and planning contribute to the conditions of justice and injustice in cities, neighborhoods, and the public realm, and asks whether design can have an impact on correcting urban injustice, inequality, and disparity. Through ongoing research and dialogue, the Just City Lab has developed a series of tools for assessing and engaging with social and spatial justice issues, and these observations form the heart of Design and the Just City in NYC. Learn more about Design Labs at the GSD.

“There is growing interest among design and planning professionals and students to address issues of social and spatial injustice and disparity,” said Griffin. “Our team of student research assistants at the GSD are creating platforms for dialogue and profiles of practice that we hope prove the possibility of dismantling injustice.”

At the exhibition’s core is the Just City Index , a guide offering an itemization of 50 city- and community-building values and indicators—along them, acceptance, choice, democracy, mobility, and resilience—and a breakdown of the various definitions and approaches to fostering each value. Below, see photos from the exhibition’s GSD installation, and from the exhibition’s January 10 launch at the AIA Center for Architecture.

Design and the Just City in NYC also presents case studies and video conversations with a variety of voices, inviting visitors to contemplate the intention and effectiveness of design practice to address issues of social and spatial justice. In addition, an interactive map will invite visitors to determine what values they most associate with their neighborhoods, allowing them to plot collective manifestos for what might constitute a “just city.”

“Design and the Just City in NYC resonates with AIA New York’s 2019 presidential theme, BUILDING COMMUNITY, which asks members and professionals how they can contribute to communities inside and outside the profession. To this end, we are pleased to work with Professor Toni Griffin and her students from Harvard GSD, who have expanded their research to present a range of NYC projects,” said Benjamin Prosky, Assoc. AIA, Executive Director, AIA New York | Center for Architecture. “We are eager to share this work with our extended community as they continue to express interest in better understanding how design interventions can promote equity, especially at a time when cities have become places of extreme privilege and extreme poverty.”

For its Center for Architecture installation, the exhibition takes up five case studies in New York:

• D15 Diversity Plan, led by WXY, a community-based effort to make schools in Brooklyn’s District 15 more diverse and integrated

• Justice in Design, led by the Van Alen Institute, a plan to develop healthier and more rehabilitative jail infrastructure

• Center for Living and Learning, led by Perkins Eastman, which transformed an underutilized space into a community-driven, mixed-use space

• Under the Elevated, led by the Design Trust for Public Space, an initiative that reclaims spaces beneath high infrastructure for the public

• Public Life and Urban Justice in NYC Plazas, led by Gehl Studio, the J. Max Bond Center at Spitzer School of Architecture CCNY, and Transportation Alternatives, offering a study that evaluates effective public life and social justice in public space through a framework of metrics.

To learn more about Design and the Just City in NYC, visit the AIA’s website , and to learn more about Griffin’s Just City Lab, visit the lab’s website .

2017 Black in Design Conference examines where and how design and activism intersect

Empowering; uplifting; sobering; timely; necessary. An event that evades simple distillation, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s 2017 Black in Design Conference evoked a range of immediate reactions, as well as a charge for sustained dialogue over the many issues it positioned within its programming.

Organized by the GSD’s African American Student Union (AASU), the 2017 Black in Design Conference was inspired by its inaugural predecessor, held in 2015, but was charged with urgency given the shifts in the nation’s cultural and political climate over the past two years. With a theme of “Designing Resistance, Building Coalitions,” Black in Design 2017 sought to recognize the contributions of the African diaspora to the design fields, as well as to “explore design as resistance and show how designers are advocates and activists”—a mandate relevant to the country’s current political tenor. (View the entire 2017 Black in Design Conference via the GSD’s YouTube channel, where the full conference is available and organized by session, and see a photo gallery of select moments below.)

GSD student leaders from AASU began conceptualizing Black in Design 2017 in fall 2016, spending much of the following months in dialogue over which speakers to invite, which themes to prioritize, and how to scaffold the wealth of ideas and thematic touch points within the context of a three-day conference. Organizers began their planning work in earnest in March 2017.

Around that point, conference organizers coalesced as a planning committee, including Natasha Hicks (MUP/MDes ’19), Marcus Mello (MArch/MUP ’18), Amanda Miller (MDes ’17), Armando Sullivan (MUP ’18), and Chanel Williams (MUP ’18). The committee were advised by collaborators including urban planner Justin Garrett Moore, who spoke at the 2015 Black in Design Conference, and 2015 conference co-chair Courtney Sharpe (MUP ’16).

While the 2015 conference proposed scalar themes—starting with discussion of buildings, then moving upward in scale to neighborhoods, cities, and regions—this year’s organizers chose value-driven topics to structuring the conference’s various sessions: Exploring and Visualizing Identities; Communicating Values; Mobilizing and Organizing; and Design Futuring.

These themes were structured to form conversations around topics and skills integral to so-called “design activism,” according to conference organizers. (Design activism refers to the activation of designers’ creative agency toward catalyzing and generating alternatives to normalized ways of living, working, and thinking—or, applying design creativity and strategy toward proposing new ways of living and thinking.)

Powerful keynotes framed the entire conference; LAXArt executive director Hamza Walker opened the conference on Friday evening, October 6, and activist DeRay Mckesson provided closing thoughts at the end of Saturday, October 7. As in 2015, sessions were interwoven with interludes that enriched discourse as much as they entertained audiences; some of this year’s diversions included yoga, dance, and spoken-word performances.

Throughout the conference, the core thematic sessions enabled conversations that delved into given subject matter. Panelists included designers and leaders from across the country—as did the audience. (A number of schools and organizations, including Washington University in St. Louis’s Sam Fox School and Bowie State University, arranged group travel for their respective attendees.)

In addition to two noteworthy keynote addresses, a Saturday morning presentation from speaker Courtney D. Cogburn, during the “Exploring and Visualizing Identities” session, struck many conference attendees and organizers as a highlight. Cogburn, whose research focuses broadly on the role of racism in producing racial inequities in health, offered a virtual-reality presentation illustrating day-to-day experiences of an African-American male, and discussed connections among social inequity, the built environment, and health and the body.

Another moment that resonated post-conference: GSD professor Toni L. Griffin’s Sunday morning Just City Lab workshop. Among other activities, Griffin runs the GSD’s Just City Lab , one of the School’s nine such “Design Labs” that synthesize theoretical and applied research and knowledge. Griffin’s Just City Lab addresses some of the themes and questions that Griffin has worked with over the course of her career: how design and planning contribute to the conditions of justice and injustice in cities, neighborhoods, and the public realm. Griffin and the Lab ask: would we design differently if equality, inclusion, and equity were the primary drivers behind design?

During her Sunday presentation, Griffin asked categories of individuals to stand up in the audience.

“I need the black brothers to stand up,” she began.

“I need the women in this room to stand up,” she continued.

“If you are a proud member of the LGBTQ community, I need you to stand up.