Whispered Stories: Le Corbusier in Chandigarh

In 1950, the Indian government commissioned Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier to design the city of Chandigarh. The project is often seen as marking a new era of modern architecture in South Asia. Records housed in the Frances Loeb Library at the GSD reveal the challenges of the monumental project as well as its influence and legacy. This semester, Graduate School of Design students Rishita Sen (MArch II 2025) and Neha Harish (MArch II 2025) organized a conversation on India’s rich history in modernist architecture, inspired by the Le Corbusier collection in the Frances Loeb Library Archives and Le Corbusier’s design of Chandigharh.

In collaboration with Rahul Mehrotra, John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization, and Ines Zalduendo , Special Collections Curator, the group met one evening to view historic objects and share stories that Mehrotra gathered as a result of his proximity to Le Corbusier’s community in India. The gathering is part of a series of “Archives Parties” that Zalduendo offers to the GSD community in collaboration with professors, student groups, and others interested in focusing on a particular theme or subject within the library’s collections.

“We represent a group of South Asian nations at the GSD,” said Sen, “and, because Neha and I are both so familiar with how modernism came to India, we wanted to pay homage to what we know, while setting the stage for future conversations focused on a range of South Asian nations and themes.”

The story of modernism in India starts with its independence from Britain in 1947, when the nation embraced the opportunity to define its identity through architecture and design. While “revivalists” attempted to reinvigorate older forms of Indian architecture to signify this new moment, Jawaharlal Nehru, the nation’s first prime minister, “embraced modernism as the appropriate vehicle for representing India’s future agenda,” writes Mehrotra in Architecture in India Since 1990. Modernism was free of associations with the British Empire and symbolized the pluralistic nation’s desire to be “progressive” and globally connected. Earlier in the century, Art Deco had become popular, introducing the use of reinforced concrete by the Maharajas, explained Mehrotra, and aligning Art Deco with opulence. At the same time, starting in about 1915, Gandhi constructed ashrams with a an aesthetic that grew out of frugality, creating an association between modernism and Gandhi’s ethics of “minimalism,” and the ethos of today’s environmentalism and sustainability.

In 1950, Nehru commissioned Le Corbusier to design Chandigarh, setting in motion the country’s nascent development program and national identity under the era’s premise that, writes Mehrotra, “architects could shape the form not only of the physical environment but of social life.” A culture could be determined by its design.

At the Frances Loeb Library Archives, Harish, Sen, Mehrotra, and Zalduendo gathered with staff, faculty, and students to discuss a range of objects from the university archives as well as Mehrotra’s personal collection. Mehrotra noted how refreshing it was to be able to speak conversationally about these histories, within the context of the typically more formal archives at an institution.

“We were interested in engaging with oral histories,” said Harish, “which have been reiterated over the years.”

“Having grown up in Bombay,” said Mehrotra, “and having known architects who worked in that time, I heard many stories about who went to receive Corbusier at the airport when he travelled from Paris to make his connections to Delhi, or for his projects in Ahmedabad, etc.. Also how in his stays in Mumbai, Doshi and Correa walked with him on Juhu Beach, discussing architecture.” Some of the “whispered accounts” that circulated in the community between Le Corbusier and other architects and contractors in India from the 1950s to 1970s were evident in letters Mehrotra shared. In one, from Le Corbusier to the Indian government, the architect stridently requests an overdue payment. “Everyone believes that Le Corbu received incredible patronage in India,” said Mehrotra, “but, in fact, it was an uphill task, and, as was evident in the letter I shared, the man was going to go bankrupt.”

In other correspondence, notes Harish, “we saw the concept of jugaad,” a Hindi word meaning “make do with what you have,” as Le Corbusier had to “mend and mold the concrete every step of the way. Once he’d had this experience with the concrete looking so handcrafted in India, he could never replicate it anywhere else.” Le Corbusier used concrete for the construction of Harvard’s Carpenter Center , the only building he designed in North America , completed in 1963.

Mehrotra’s revised and updated Bombay Deco (Pictor Publishing), written with the late Sharada Dwivedi, was released in December 2024, and speaks to the history of Art Deco in India. In 2018, Mumbai’s collection of Art Deco buildings, the second largest in the world, was named a UNESCO World Heritage site. Le Corbusier’s use of concrete in Chandigarh rose out of that Art Deco tradition in Mumbai.

“Art Deco resulted in the creation of a whole industry that could produce reinforced concrete,” Mehrotra explained. “So, for Le Corbusier, the technology developed over 30 years. If Art Deco hadn’t happened [in Mumbai], and we weren’t using reinforced concrete, he couldn’t have built Chandigarh—because that’s the material he knew.”

The group also discussed Le Corbusier’s relationship with other key figures, including his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, who collaborated with him on building Chandigarh. Jeanneret and Le Corbusier had practiced together in France for over a decade, until 1937, and then, alongside the couple Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, reunited to design and construct Chandigarh.

Finally, the group celebrated the role that British urban planner Jacqueline Tyrwhitt played in developing architectural projects and discourse in South Asia in the 1940s and ’50s. Trywhitt worked with urban planner Patrick Geddes, editing Patrick Geddes in India, published in 1947, and was a United Nations technical assistance advisor to India and member of the 6th Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) in 1947. She served as a professor at the GSD from 1955 to 1969, and, as Dean Sarah Whiting explained, “helped establish and fortify the urban design program in its founding years.” An urban design lectureship named in her honor continues to support visiting scholars at the GSD today.

A Quilt Makes a Home

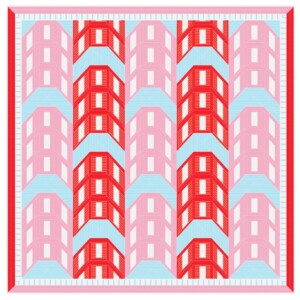

Rosie Lee Tompkins’s quilts gained worldwide acclaim when the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) mounted an exhibition of some of the more than 700 of her works that were donated by collector Eli Leon. Known for her bold use of color in an improvisational piecing style that breaks conventional bounds, Tompkins’s work was first shown in 1988 and has since been included in the Whitney Biennial, among many other museums and galleries. While William Arnett famously drew an alliance between quilts and architecture in his 2006 book, The Architecture of the Quilt, about the African American quilting collective Gee’s Bend, a spring studio at the GSD led by Sean Canty, assistant professor of architecture at the GSD, played with the inverse of this idea.

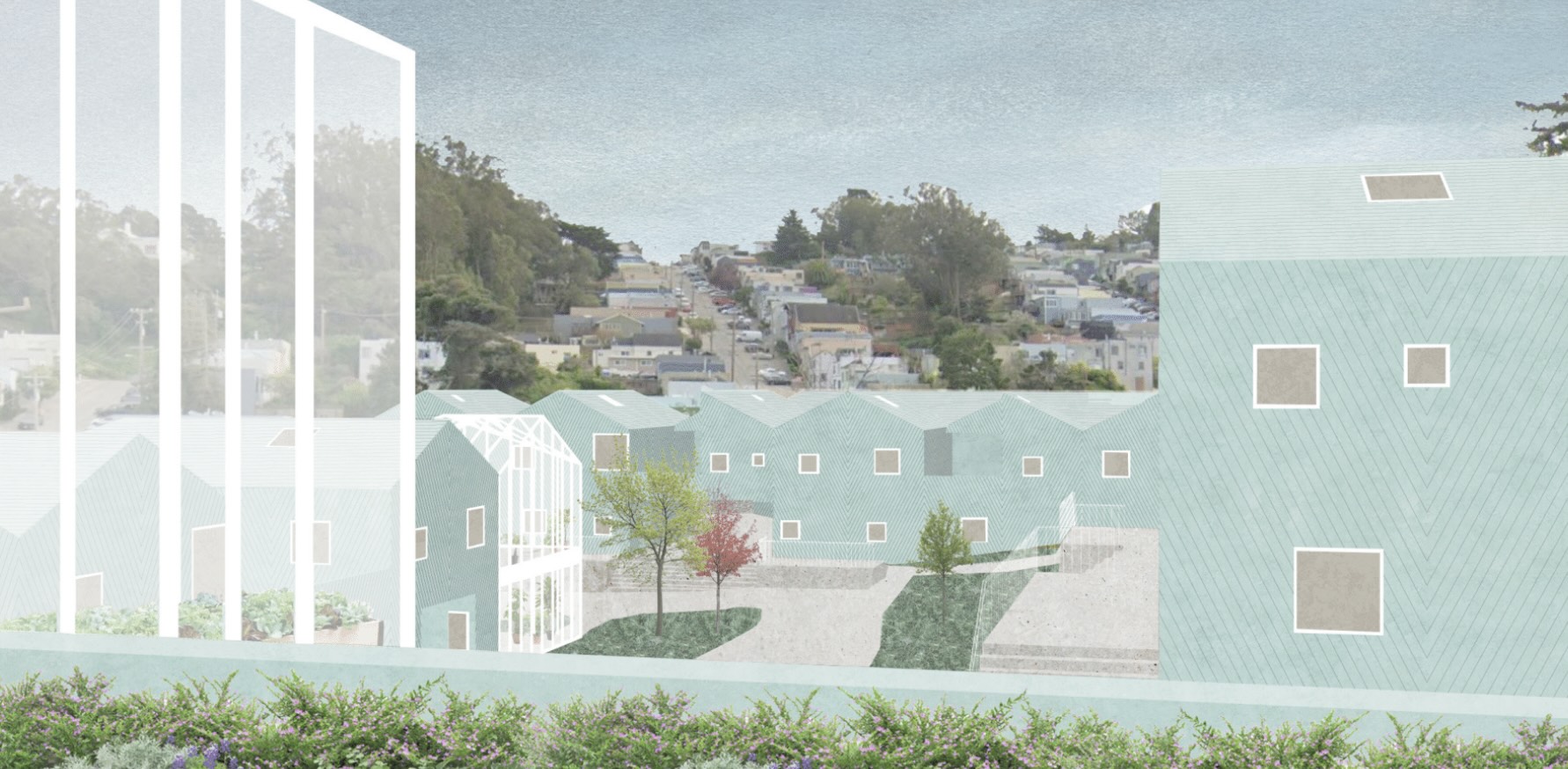

In “Soft Slants, Mixed Gestures” students took inspiration from Tompkins’s work to create designs for housing and green space in the Portola neighborhood of San Francisco—an area known as the city’s Garden District for its history of nurseries and greenhouses that supplied the city with flowers.

In a region fraught with NIMBYism and gentrification, the site has become a flashpoint for conversations around development, the history of colonization, and racism—even appearing in the opening scene of the 2019 film The Last Black Man in San Franscisco, which the class viewed this semester.

The class visited Tompkins’s quilts in person at the BAMPFA during their California trip this winter.

Drawing from the works’ sense of color and motion, triangular piecing, and the language sewing offers including such as “threads,” “stitching,” and “seams,” the quilts became both literal and figurative inspiration for their designs.

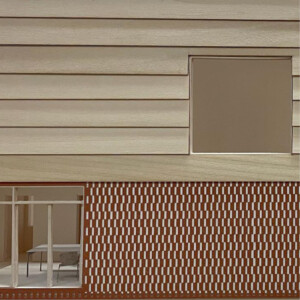

Canty selected ceramics as an intermediary that students could apply to their designs’ skins, walls, or flooring, in similar patterns as a quilter might piece a top.

Framing the semester with theory that connects architecture and quilts, Canty established a conversation around Black artists, queer phenomenology, and the architecture of San Francisco, launching the semester by reading with students Florence Lipsky’s urban design treatise San Francisco: The Grid Meets the Hills.

Like most of the western United States, Lipsky explains in her book, San Francisco was colonized and designed with “the Jeffersonian grid,” or Public Land Survey System, established in 1785 to divvy up vast acres into organized, heterogenous squares and rectangles.

In most cities and towns across the United States, the grid meshed relatively seamlessly with the landscape.

“The problem Lipsky defines,” explained Canty, assistant professor of architecture at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), “is that most cities in the United States aren’t as topographically diverse as San Francisco, so a survey system originating in river towns, coastal cities, and plains doesn’t work in the same way here.

In a series of what Lipsky calls “urban episodes,” she argues that the grid is forced to bend and change with San Francisco’s unique natural setting. As Canty summarized, the grid is “incommensurate with the topography.” Urban planners had to innovate to maintain through-lines along streets and neighborhoods, thereby disrupting or softening the grid. “In a grandiose landscape,” writes Lipsky, “where bridges and highways unite sea and land and where every hill forms a neighborhood, Nature and Architecture blend to compose a city that is alternately triumphant, modest, and familiar.”

For example, Canty explained, a sidewalk accommodates a hill by transitioning into a stairway, a switchback is paired with a tunnel to move through the hill, a road dead-ends and “overlooks the street that runs perpendicular to it, underneath.” Such idiosyncrasies “produce something spatially exceptional,” Canty said—a surprising, sometimes even slightly dizzying, delight, not so unlike Tompkins’ quilts.

“This became the concept of the slant for me—something that’s slightly off-kilter or new, as a subject-position in terms of queerness, and as a spatial practice within the city.”

The “queer slant” is described by cultural theorist Sarah Ahmed in her book Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others, an excerpt of which Canty and his students read at the outset of the semester, along with bell hooks’ “An Aesthetic of Blackness: Strange and Oppositional.” Ahmed speaks to orientation and defines the “queer moment” as a time when things are “out of line” and “appear at a slant,” asking how the slant moment can inform our subject-positions, our relationships to objects and the world around us.

bell hooks similarly considers the objects in her domestic space as they define her aesthetic. “Black domestic life,” she writes, “cultivates a rich, oppositional aesthetic rooted in everyday acts of homemaking.” Canty noted that hooks grew up with a grandmother who made quilts. hooks argues that her creation of the domestic space was its own art: “The way we lived was shaped by objects, the way we looked at them, the way they were placed around us,” and that, “we ourselves are shaped by space.”

In class, Canty discussed work by Diller and Scofidio in which the designers fold and crease work shirts in unconventional ways, so that the functional objects transmute into sculptural forms—just as Tompkins’s quilts extend beyond their medium into the realm of abstract art. Both offer a way of thinking about fiber that Canty sees as a bridge to architectural forms. He explained that Diller and Scofidio’s work shirts, like Tompkins’s quilts, they “reveal how architectural thinking can be embedded within complex formal systems beyond the discipline itself.”

The creases and folds created with work shirts become “allegories for architecture—sites where social, formal, and political conditions are folded together and made visible.” This idea of translating quilted pieces and shirts to architecture became evident in the students’ initial exercises in the class as well as their final projects, where the buildings they designed opened and layered upon one another in mimicry of fabric.

As Canty was designing the course, he was also at work on his book, Black Abstraction in Architecture , forthcoming from Park Books in November 2025, in which he analyzes “modes of abstraction that are outside the traditional canon,” which he explained the profession is still wrestling with in the years since George Floyd’s murder and the Black Lives Matter movement. In search of “an urban imaginary that comes from a Black aesthetic,” he studied the work of Theaster Gates, David Hammons, and Amanda Williams.

In Color(ed) Theory , Williams, an artist and architect (and one of Canty’s professors as a graduate student) painted condemned houses in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood in a range of vivid colors that reflect Black experience and consumerism. Canty’s studio makes the argument that Tompkins’ work falls within the realm of Black Abstraction as well, and, with its asymmetrical blocks and color schemes, offers a creative space in the spirit of the “queer slant,” through which students can reimagine housing typologies in the Portola neighborhood—a site with a literal slant, rising 40 degrees from one side to the other.

Armed with this theoretical background that connects African American art and theory, queer theory, and urban design, students headed into the field. The site, 770 Woolsey Street, sits in a diverse neighborhood that has been home to a wide range of immigrant communities ever since the indigenous tribes of the Ramaytush Ohlone were displaced by settlers in the eighteenth century.

The plot holds remnants of eighteen greenhouses, on more than 20,000 square feet, where roses and marigolds flourished. From the 1920s to 1990s, greenhouses around the neighborhood provided all the cut flowers for the city, giving the neighborhood its moniker, “The Garden District.”

Now, the remaining twelve greenhouses sit dilapidated, portions of the roofs broken or sagging to the ground, untended weeds rising high. In a city that’s rapidly being gentrified and developed, with a desperate need for housing units, the site has become hotly contested. Community groups such as The Portola Green Plan and 770 Woolsey have advocated for accessible green space and affordable housing that retains the plot’s history, even as the developers who own the site have vacillated between selling and building for the last several years.

Invited studio critics Lisa Iwamoto, chair and professor of architecture at California College of Art (CCA), and Craig Scott, professor of architecture at CCA, created a series of proposals for the site, and Mark Donahue, associate professor and chair of the BArch program at CCA, taught two studio courses on the site, sharing his survey with Canty’s students. Also invited to offer student critiques was Matthew Au, faculty member at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), whose studio Current Interests creates quilts together as part of their practice.

The studio’s program required 40–80 residential units, integrating and repurposing the existing green space, establishing a public commons, and exploring the concept of a ceramic enclosure. Local ceramic manufacturer, Heath, opened its doors to the class so that they could explore using tile—a material that’s “mass-produced but carries the feeling of being bespoke,” said Canty—in the facade and enclosure of the buildings and site.

The resulting designs included playfully oversized red siding, housing units situated as triangles rather than squares, using the concept of the fold to create multi-directional skins, and carefully curated interiors intended to foster community art-making and creativity.

Ashleigh Brady (MArch ’26), “Common Threads”

“This project explores domesticity through a formal language inspired by the geometric logic and improvisational ethos of Black American quilt making traditions, particularly through the work of Rosie Lee Tompkins, Chaney Ella Peace, and other Black women whose textile practices operate as radical acts of care, memory, and spatial invention.

Rooted in the programmatic design of ‘Common Threads’ is the legacy of Black San Franciscans whose resilience manifested through the transformations of the domestic sphere and public realm alike.

Porches, yards, and improvised additions became expressions of cultural identity and spatial autonomy. Citizens reclaimed land as communal infrastructure-spaces where food, kinship, and memory were cultivated side by side. These improvisational programmatic practices formed a spatial language of care and adaptability that this project adopts as both historical precedent and evolving methodology.”

“Garden in a Courtyard in a House in a City,” Sangki Nam (MArch ’25)

“This project engages the urban condition of San Francisco as a site of spatial and ideological tension, where the Cartesian imposition of the grid onto a dramatically sloped terrain has produced a landscape of unintended urban phenomena. Taking 770 Woolsey in Portola as a site of intervention, the work negotiates between competing imperatives: the preservation of local historical identity as a cultivated “Garden District” and the systemic pressures of the city’s housing crisis. Drawing on the conceptual framework of quilting, the proposal rethinks ground and form as interdependent, generating a domestic topography that dissolves binary distinctions between public/private, interior/exterior, and formal/informal, generating a spatial fabric that softens divisions between opposing realms and proposes a new model of domestic living.”

“House-fold: Playing with Household,” by Brandon Soto (March ’26) “This project reads the quilts of Rosie Lee Tompkins as a starting point for spatial exploration, seeking alternative but familiar form. Drawing from Tompkins’s quilts and Sara Ahmed’s Orientations: Toward a Queer Phenomenology, the project challenges conventional domestic aesthetics through a queer, oppositional stance.

The pre-existing gabled bar is transformed by the stitches in Tompkins’s work, mirroring and folding figures in the interest of the off-center and non-uniform. The facade reacts similarly, reflecting topographical conditions as distortions to tile compositions, highlighting ‘seamlines’ between building and ground.”

These acts of folding and layering imagine a new queer domestic identity, answering to underlying visual traditions and cultures not fully realized in built domestic space.”

“Threaded Ground, Tending the Seam,” by Meagan Tan Jingchuu (March I ’26)

“Structuring collective housing through two spatial datums, Threaded Ground refers to how architecture navigates San Francisco’s extreme topography—slipping between indoor and outdoor, residential, and shared space—through a plan-driven strategy of adjacency and maneuvering. Tending the Seam describes a sectional logic: a continuous roof seam that generates difference, connection, and circulation.

Together, they frame an architecture shaped by Sara Ahmed’s notion of orientation—attuned to how bodies move, align, and relate within space—and guided by a quilt logic of variation through aggregation, scale, and tactile differentiation. Across three scales of courtyard voids and long, shared seams, publicness drifts. By shaping spatial thresholds and shared seams, the architecture enables life to accumulate and unfold organically—through repeated gestures, material traces, and collective use over time.”

“Arrangements between Garden and Grid,” by Emanuel Cardenas (March II ’26)

“Along with the greenhouse history, vivid residential color palette, and sprawling gardens that make the Portola neighborhood known as San Francisco’s Garden District, the project draws from the act of quilting and San Francisco’s first master planning, in which Market Street acts as a converging line between two regular but misaligned organizational grids. The fragmented in-between spaces adjacent to Market Street are reminiscent of imperfect singular patches stitched together to form a quilted whole. Lone star quilts are traditionally constructed with Y-seams, where three separate fabrics fold onto one another and are stitched together to form a Y. The project adopts a similar strategy to quilt a figure ground from a standard perimeter block organization. These Y-seams become the central circulation within each cluster of homes and shared spaces, seaming together multiple fabrics of architectural orientation nestled in a cascading landscape of gardens.”

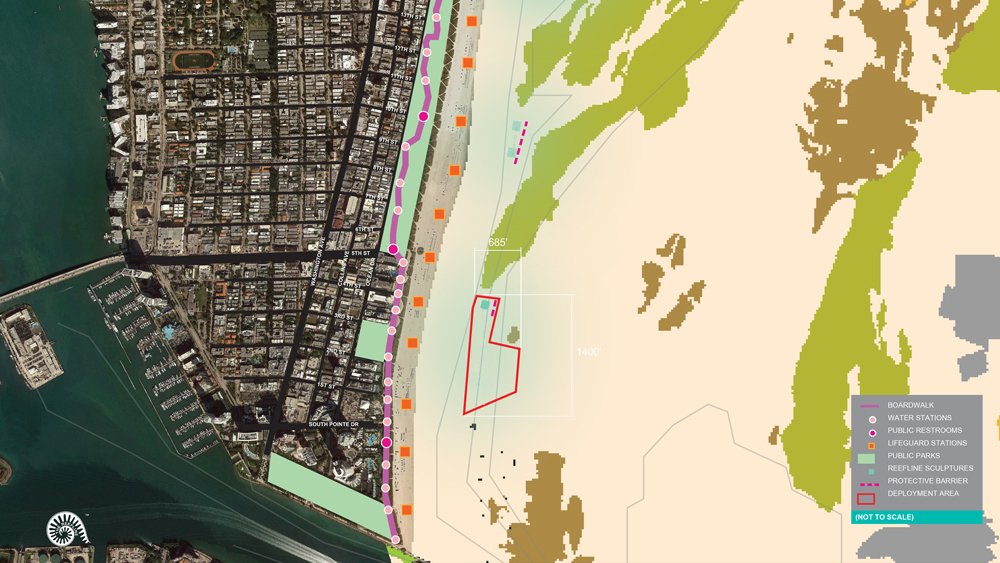

The ReefLine: An Unprecedented Underwater Sculpture Park Brings Art, Marine Habitats, and Public Education to Miami Beach

A 7-mile underwater sculpture park and hybrid reef will soon trace the shore of Miami Beach. Known as the ReefLine , this first-of-its-kind project fuses public art, science, and conservation to address threats posed by the climate crisis, in particular sea level rise and warming ocean temperatures. At the same time, the ReefLine offers an innovative model for cooperation, situating art as a catalytic force that transcends disciplines and fosters wide-spread environmental stewardship. As the project’s founder and artistic director Ximena Caminos recently asserted in a lecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), the ReefLine “forces alliances between artists, scientists, engineers, architects, and communities. . . . Through storytelling, cultural practice, and knowledge, we translate complex science into shared emotional understanding and collective responsibility.”

Charles Waldeim, John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture at the GSD and co-head of the MDes program, introduced Caminos to the GSD audience. “Beyond the importance of Ximena Caminos’s work, what’s so powerful about the ReefLine is that it is a new paradigm,” Waldheim declared, “a new category of work that hadn’t existed before at the intersection of arts, design, and environmental stewardship.”

Throughout her career as a curator, artistic director, and cultural placemaker, Caminos has used art to foster community development and raise awareness about topics she holds dear. For example, in her homeland of Argentina, Caminos worked with conceptual artist Jenny Holzer to highlight the abuses of the country’s former military government. Two decades later, she orchestrated a commentary on the climate crisis with Leandro Erlich’s Order of Importance (2019), a traffic jam of 66 full-size automobiles, sculpted from sand, in Miami Beach. More recently, she curated the art master plan for the UnderLine , a 10-mile linear park on formerly fallow land beneath Miami’s Metrorail.

“To me, everything starts and ends in the ocean,” says Caminos. It seems natural, then, that with the ReefLine, Caminos has focused her attention on the marine world. Following preliminary funding from the Knight Foundation’s Knight Arts Challenge in 2019, Miami Beach residents voted in 2021 to issue a $5 million bond for the project. This sparked years of collaboration between disciplinary experts (art, architecture, technology, science), governmental authorities (city, state, federal), and local communities—all stakeholders in the ReefLine, which Waldheim aptly described as an “audacious adventure.”

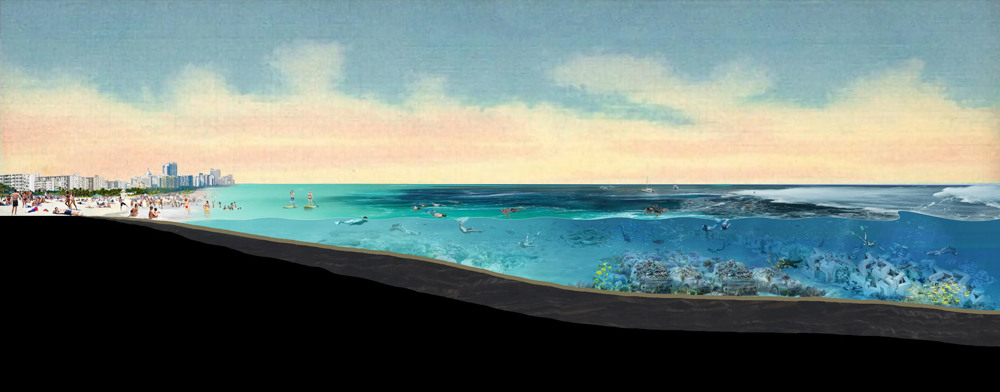

Located 600 feet offshore at a depth of 20 feet, the ReefLine begins off South Beach and runs north, featuring large-scale installations that simultaneously comprise a public sculpture park and a hybrid reef, intended to enhance biodiversity in an area ravaged by decades of sand replenishment and dredging operations. Experts estimate that, since the 1970s, 90 percent of the Florida coral reef tract has been destroyed , harming the underwater ecosystem and leaving the land even more vulnerable to rising sea levels and storm swell. Caminos and her team envision the ReefLine as providing much-needed coastline protection and, of equal importance, encouraging public interaction with—and education about—the marine environment.

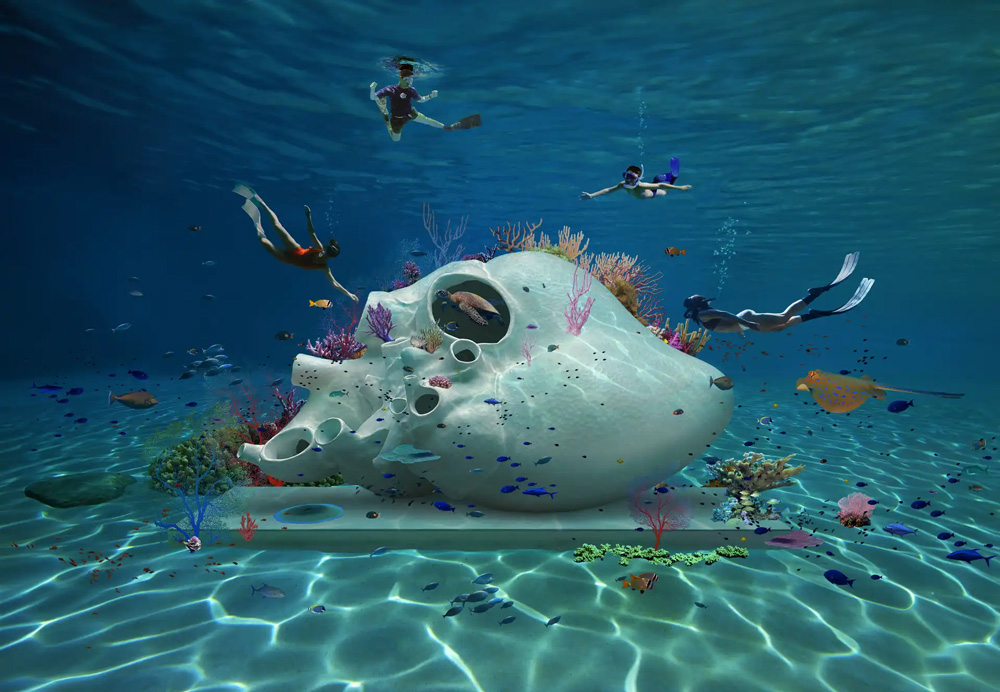

The first sculpture/hybrid reef will be installed in early September. Designed by Erlich and called ConcreteCoral, the work reprises the artist’s earlier land-based installation with 22 automobiles, which have been cast in environmentally friendly concrete using 3D-printed molds. Innovative insets (Coral Loks ) will attach living coral to vehicles, fostering a vibrant submerged garden for marine life to explore alongside willing snorkelers, who can simply venture out from the beach, no boat or fee required.

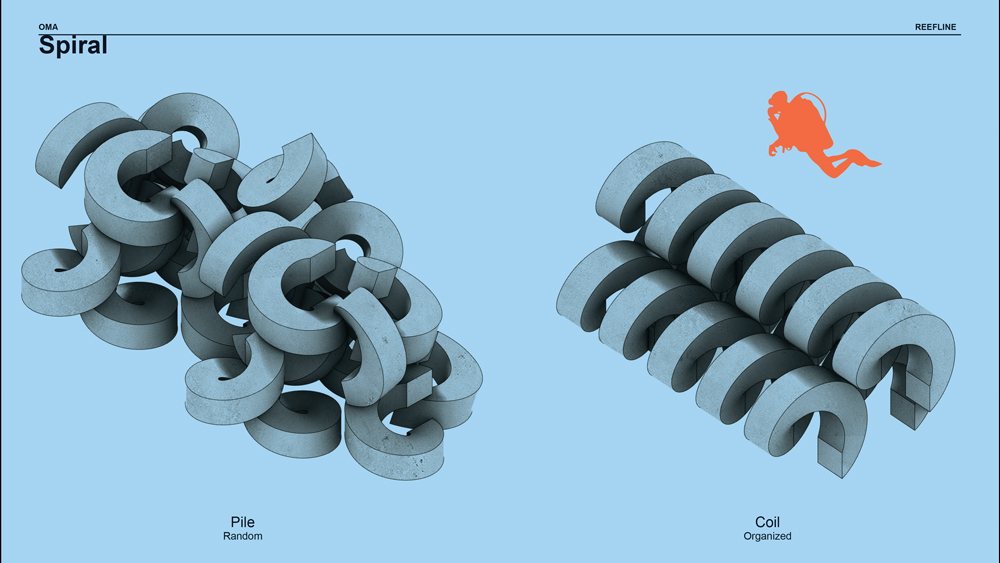

In the next two years, more sculptures will follow Concrete Coral, adding to the ReefLine’s “snorkel trail.” British artist Petroc Sesti modeled Heart of Okeanos on the heart of a blue whale and fashioned the sculpture from CarbonXinc , an experimental eco-concrete that acts as a carbon sink. Coral scientists will seed living corals in the 17-by-9-foot module, while sea creatures colonize its plentiful openings. With the Miami Reef Star, fifty-six 3D-printed concrete starfish congregate in the shape of a giant star. Designed by artist Carlos Betancourt and architect Alberto Latorre, the 90-foot-wide sculpture will be public artwork, marine habitat, and visual icon, visible via air upon approach to Miami International Airport. And a series of interlocking concrete elements—designed by OMA/Shohei Shigematsu, also responsible for the ReefLine’s master plan—will form a protective barrier against sand migration and serve as another surface on which coral may grow. Additional eco-conscious sculptures by artists from around the world, selected through a new Blue Arts Award competition, will join this collection in the future.

The ReefLine encompasses more than underwater sites, with educational components that connect the submerged installations with events on land. For example, in December 2024, the annual Art Week in Miami Beach featured a version of the Miami Reef Star arranged on the sand, as well as physical signage and digitally accessible images of the corals that will soon flourish offshore. Temporarily installed on the beach, the Miami Reef Star received more than one hundred thousand visitors throughout the festival’s seven-day run. It also drew the attention of officials organizing the 2025 United Nations Ocean Conference in Nice, France, which will now feature a twin reef star on its Mediterranean beach.

In Miami Beach, Caminos’s team has plans for the ReefLine Pavilion & Biocultural Center, situated along Ocean Drive in the popular waterfront Lummus Park. The structure, to be 3D-printed like the Miami Reef Star, will house a learning space, coral demonstrations, gift shop, and multipurpose event space. Caminos also envisions the ReefLine Salon, a regular meet-up modeled on the social salons of early modern France where individuals across disciplines will gather to informally share ideas.

Following her presentation, Caminos spoke with Pedro Alonzo, a curator, art advisor, and GSD lecturer who recently taught a course for MDes students on curation in the public realm. The discussion focused on the power of art, with Caminos commenting that “art has the power to open doors where doors don’t exist. I think that’s a hack,” she explained, and the ReefLine offers a perfect example. An incredibly complex project, the ReefLine doesn’t fall into any neat category; funding comes from a cultural grant, while a hybrid reef permit allows for its creation. Yet, Caminos emphasized that, while the ReefLine straddles art and science, art—not science—“actually unlocked the funds and the imagination of the people,” the citizens of Miami Beach who overwhelmingly support the project. “Neuroscience now confirms what artists have always known,” Caminos declared earlier in her talk; “empathy and narrative move people much faster than numbers do.”

Caminos also highlighted how the ReefLine sculptures are “doing the work and not representing it; [the art] is the environment and is serving the environment.” Alonzo echoed this sentiment. “Art tends to be symbolic, representational, and the ReefLine transcends that. Some of this work functions as a carbon sink,” he commented. “This is all very important.”

Waldheim agrees. “A mix of habitat creation, biodiversity, addressing the climate crisis directly, the ReefLine is absolutely as innovative and progressive a model for the arts and design as I’ve seen anywhere else in the world. And we are so very thrilled that Ximena came to share it here with us.”

Igniting Radical Imagination

“Think about someone who harmed you deeply. What would it take for you to sit down across from them, and ask them, Why? What supports would you need?”

This is one of the prompts that Deanna Van Buren, architect, activist, and director of Designing Justice + Designing Spaces (DJDS), asked the audience to consider during her talk, “Designing Abolition,” on Tuesday, March 4, at the Graduate School of Design (GSD).

After her presentation, Van Buren was joined in conversation by her collaborator Andrea James , an activist, lawyer, and community organizer whose goal is to end incarceration for women and girls.

Van Buren designs systems of care that replace the carceral system. Her organization’s buildings focus on community-building and restorative and transformative justice—spaces where people can have healing conversations to resolve conflict, get support finding jobs and childcare, grow and prepare healthy foods, and work with community members to support the neighborhood.

Diverting people out of the prison system and into systems of care requires collaborating across industries. For example, Van Buren worked with lawyers, prosecutors, asylees, and others in Syracuse, New York, supporting The Center for Justice Innovation to open the Near Westside Peacemaking Project , the country’s “first center for Native American peacemaking practices in a non-Native community.” Now, instead of sending people to prison, judges can send them here for support within the neighborhood. The center features a Women’s Reentry Lounge, Circle Event and Art Space, Youth Zone, and Welcome Lobby. People have come to congregate at the center, gardening together in the yard, and using it for quinceañeras and engagement parties. This, says Van Buren, moves people from “incarceration to community cohesion. Prisons don’t keep people safe; this keeps people safe.”

In California, the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights launched Restore Oakland the nation’s first center for restorative justice and restorative economics, which prompted Van Buren to create the real estate side of DJDS to acquire properties in ways that best serve communities. DJDS also supported Allied Media Projects to develop the LOVE Building in Detroit, Michigan, a commercial space with offices for nonprofits, which inspired DJDS to pursue the Grand River at 14th Parcel Assembly, with additional facilities for family support, youth activities, food justice initiatives, workforce development programs, education and literacy training, health and wellness services, and arts and culture groups. DJDS also designed the Common Justice Headquarters in New York, which serves victims of violent felonies and diverts people from prisons, as well as mobile refuge rooms to house formerly incarcerated people, exhibited at the Smithsonian Design Triennial under the title “The Architecture of Re-Entry.”

Restorative justice, transformative justice, and trauma-informed design are at the foundation of Van Buren’s practice, which she developed in part during her 2013 Loeb Fellowship , after working as an architect for 12 years. At the GSD, she described how she thinks about designing a room where people can have difficult conversations—the core of restorative justice, whose premise is that harm can be resolved without punishment, and that with the right supports in place, people can thrive. “A core part of what it means to be human,” Van Buren explained, “is conflict and resolution. We avoid it. We don’t have skills. We don’t practice it.” Rather than sending someone to jail for attempted murder, for example, the two parties can sit in a room and talk to one another. Designing a space like this requires a deep understanding of trauma and how it works at the physiological level. “If you’re going to go into a conversation that’s very traumatizing…you need an environment that’s going to help you with that interaction.” She described how limited views, access to daylight, art that reflects our identities, and the ability to move the chair away from the other person are just a few of the design elements that create felt safety, which calms the nervous system.

During her tenure as a Loeb Fellow, Van Buren created her own multidisciplinary course of study to develop skills she knew she’d need. “I rode my bike over the snow in Cambridge to take classes at different schools across Harvard. I took Marshall Ganz’s public narratives class at the Kennedy School, and planning with Michael Hooper at the GSD. I took a class on research methods for designers at MIT.” She enrolled in a course on analyzing visual data at MIT, and a workshop at Lesley University on Circle Keeping, a restorative justice practice that brings into conversation people who were part of an incident that caused harm. Her process was intuitive and interdisciplinary, in pursuit of “mak[ing] space for restorative justice.”

Van Buren proposed that, as we face a complicated era that some call “the great turning,” shifting from profit-focused industry to supports for people and the environment, we have the opportunity to choose how we intervene. Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s definition of abolition provided a framework for her talk and the ensuing conversation with James, which focused in large part on how to close prisons in New England as a model for nationwide prison closures and alternative systems. “Abolition’s goal,” writes Gilmore, “is to change how we interact with each other and the planet by putting people before profits, welfare before warfare, and life over death.”

Van Buren suggested that we might consider three key questions: “What do we need to dismantle? What is the world we want to build? What skills will be required?” In the US, she said, “we have a lot to dismantle.” We’re facing “centuries of gross structural inequity in every community in this country and around the world,” which is evident in tree and food deserts, rural and tribal lands disinvestment, the US’ 1969 Freeway Act, and “co-located toxic land use,” among other challenges. Prisons in the US were built on “punishment, torture, and enslavement,” which “has to be unbuilt.” And, although people are attempting to open new prisons, more than 400 have been closed in the US in the last fifteen years, most of which now sit vacant.

“Designers are world-builders,” Van Buren said. “I cannot think of anything more important for designers to do,” she said, “than to ignite radical imagination.”

She described how the Atlanta City Detention Center, a jail that housed thousands of people, could be transformed into a Center for Equity, a food ecosystem, or community space, with potential for education and housing opportunities. The secure lobbies could be reinvented as “super lobbies where people can come in and be navigated to care-based resources.” We could “reimagine the justice core.” She illustrated this point with a map of the city’s justice system—the courthouse, police station, schools—and emphasized the importance of choosing an easily accessible site for the restorative justice center that is close to the justice core.

Instead of turning to punishments when people hurt one another, transformative justice views the harm as “a breach of relationship.” The people harmed need to “have their needs met” while the person who hurt them “makes amends.” No one, therefore, is being taken from their community, and returned to it later with the additional layers of trauma inflicted by prisons. Transformative justice helps people “heal by examining underlying issues, such as racism.”

New projects by DJDS include participation in a collaborative initiative to determine how to develop the newly closed MCI-Concord, which was the oldest operating prison in the nation, founded in 1878. Van Buren is also working with James to advocate closing women’s prisons in New England. Their focus is the last women’s prison in Massachusetts. With only 135 incarcerated women in Framingham, James argues that it would be relatively simple to close, and would mark the end of women’s prisons in the state, although the current governor is investing to construct a new women’s prison. Van Buren offers alternative models to prisons. Transformative justice spaces like the ones she created in California and Michigan divert people from prisons into systems of care, where they can find the support they need to remain in their communities.

“We have already created an exit plan for every single one of those women [in the Framingham prison]. We are uniquely poised in Massachusetts,” said James, “to close the women’s prison and create what different looks like, to become a model for the rest of the country.”

She and Van Buren continue to push to end incarceration for women and girls throughout the country, and to implement the abolitionism defined by Ruth Wilson Gilmore. In order to create new systems, Van Buren argues that we need to “develop the ability to hold complexity,” undertaking interdisciplinary collaborations to solve complex problems. To best prepare for the world that awaits them, Van Buren encouraged current GSD students to enroll in courses across Harvard’s schools in pursuit of their interests, noting that the MDes program provides a model for the kind of interdisciplinary study that helped her achieve her goals as a designer for transformative justice.

Peter Chermayeff on Taking Risks and Embracing Collaboration

For his first architectural commission, Peter Chermayeff landed a big fish: Boston’s New England Aquarium. It was 1962; Chermayeff was 26 years old, had earned his master of architecture degree from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) a mere six months prior, and didn’t yet have a license to practice architecture. He and his partners had just created Cambridge Seven Associates, a multidisciplinary collaborative firm of architects and graphic designers that would soon gain international prominence for a range of work, from small exhibitions to large mixed-use complexes.

More than six decades later, speaking about his early success, Chermayeff humbly observes: “I have a certain willingness to take risks, I suppose. And I have surrounded myself with first-rate collaborators.” Of course, his continued achievement stems from more than a penchant for risk-taking and multidisciplinary collaboration. A world-renowned authority on aquariums, responsible for high-profile projects such as the National Aquarium (1981) in Baltimore and the Oceanarium (1998) in Lisbon. Yet, the self-described “ambivalent architect” nearly didn’t become an architect at all. He had settled on filmmaking when a well-timed risk and a collaborative enterprise changed his mind.

The son of Russian-born modern architect Serge Chermayeff , Peter immigrated with his family to the United States from England in 1940 at the age of four. He and his brother Ivan (four years Peter’s senior) spent the next year with family friends—Walter and Ise Gropius in Lincoln, Massachusetts—while their parents traversed the country in search of an American outpost. Over the following decade and a half, as the father assumed a series of teaching positions (including stints in California, New York, and Chicago), the sons graduated in succession from Philips Academy at Andover. In 1953, the same year that Serge assumed leadership of GSD’s first-year program, Peter entered Harvard College with his sights trained on architecture. He majored in Architectural Sciences, which allowed him to commence graduate work after only three years of collegiate studies. Thus, in the fall of 1956, Peter entered the GSD.

Chermayeff immensely enjoyed his first and fourth years of his architectural studies, taught respectively by his father (“a hell of a good teacher”) and Dean Josep Lluís Sert (“a master and superb teacher.”) “The school was filled with energy and talent,” Chermayeff recalls. “I was intrigued by the power of the community, the quality of my classmates, and the fun we had in exchanging ideas. I was learning as much from my fellow students as I was from the faculty.”

Yet, even while enjoying his time at the GSD, Chermayeff wasn’t convinced that an architectural career was right for him. He had spent a summer in New York working for his brother Ivan, who had recently launched a graphic design firm with Tom Geismar. (Over the years, Chermayeff & Geismar would craft a plethora of highly recognizable logos including those for NBC, Mobil, PBS, and Chase Bank.) Another summer, Chermayeff worked with the Italian sculptor Costantino Nivola in his studio on Long Island as the artist created a large cast-concrete bas relief for an insurance company building in Hartford. As Chermayeff neared the end of his schooling, these endeavors prompted him to think less about architecture as a career and “more so about the visual arts, filmmaking in particular.”

During his final year at the GSD, Chermayeff had achieved unexpected success with a 15-minute experimental film. Titled Orange and Blue, the unnarrated film depicts two rubber balls, one orange and one blue, as they bounce from a bucolic wooded landscape into a junkyard strewn with the detritus of modern life. Taking a liking to the production, a film distributor paired Chermayeff’s short with Ingmar Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly as the Swedish feature toured the United States. Chermayeff found the unanticipated accolade to be “funny, ridiculous, but also wonderful.” What’s more, says Chermayeff, “I realized that, in the course of doing the film, I’d had more fun than I’d had doing anything with architecture.” So, upon graduation from the GSD, in 1962, a year when US officials were urging families to build fall-out shelters, Chermayeff set out to make another film—this time an informative documentary on the effects of nuclear weapons.

Six months later, as Chermayeff was immersed in raising funds and producing the documentary, his friend Paul Dietrich (MArch ’56) suggested they start a collaborative firm that would combine architecture, urban design, graphic design, and industrial design. Chermayeff declined; “Paul,” he explained, “I’m off in another direction. I’m making films.” Yet, the idea had been planted in Chermayeff’s mind.

The following week, Chermayeff made a bold move. He traveled to the Franklin Park Zoo in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood and, without an appointment, approached zoo director Walter Stone. “He must have thought I was crazy. I told him that I thought his zoo was dreadful,” Chermayeff recalls, “and that it could be rethought, reimagined, replanned, and changed for the better if he would allow us.” Stone was intrigued, agreeing to attend a slide presentation in Chermayeff’s Cambridge studio on how the as-yet-unnamed firm would revitalize his zoo. Impressed by their ideas but without funding to hire them himself, Stone introduced Chermayeff to the person in charge of developing a new aquarium in Boston. After a successful meeting, the fledgling firm was included on the project’s short list of architects, and an interview followed. Ultimately, Chermayeff and colleagues were selected to design the New England Aquarium—a lynchpin in the renewal of downtown Boston’. “And that,” says Chermayeff, “is how we started Cambridge Seven.”

As the name implies, seven partners initially comprised the collaborative venture: in addition to Chermayeff, four architects—Louis Bakanowsky (MArch ’61), Alden Christie (MArch ’61), Paul Dietrich (MArch ’56), Terry Rankine—and graphic designers Ivan Chermayeff and Tom Geismar, who simultaneously maintained their New York practice. They were all relatively young (Dietrich, in his mid-30s, was the elder stateman of the group). Yet the men had secured a major project, “an adventure in itself,” recalls Chermayeff, “because it involved reimagining and reinventing a building type—an urban aquarium, a place of encountering nature.” For Chermayeff, though, the New England Aquarium commission took on additional significance: “it meant that I could in fact find my way in this field because the project called for interwoven exhibition design and graphics and would address the content of things as much as the form of the envelope or the planning of the surroundings. It became, for me, place-making with a purpose, driven by content and context.” Opened in 1969, the Boston aquarium played a key role in transforming the city’s waterfront into a vibrant public locale. It also led to more aquarium commissions around the globe.

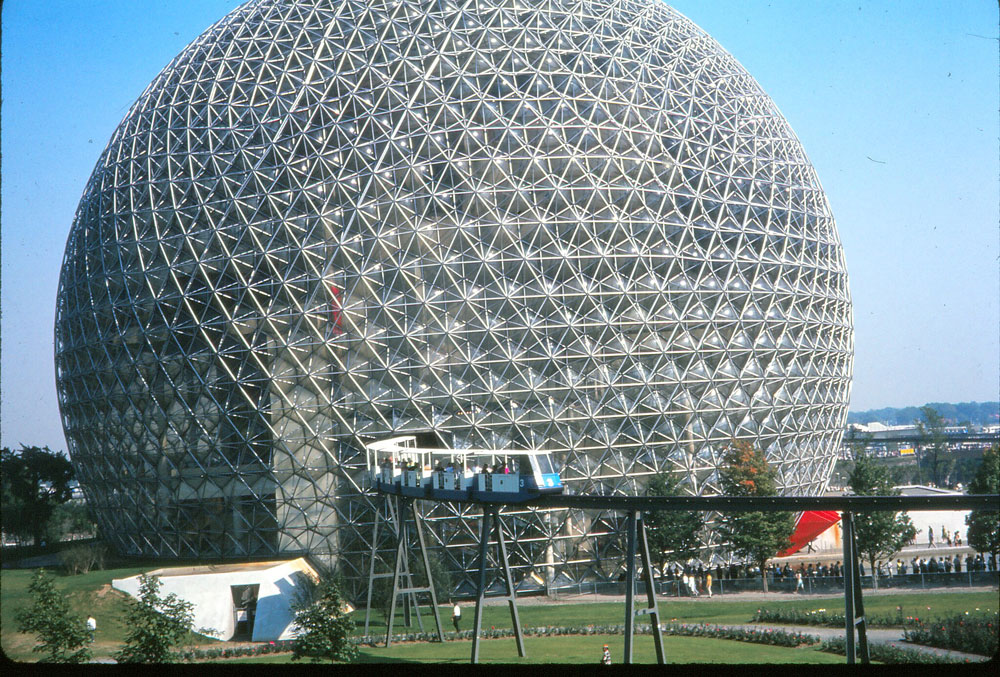

Even before the New England Aquarium’s completion, though, Cambridge Seven acquired two noteworthy projects—”not from the aquarium particularly,” Chermayeff notes, “but from the notion of the firm as a multidisciplinary collaboration.” The first arrived in 1964 when Jack Masey, design director for the United States Information Agency, invited Cambridge Seven to spearhead the US Pavilion for Expo ’67 in Montreal . Chermayeff and the others worked with Buckminster Fuller to make a transparent bubble, a geodesic dome as a three-quarter sphere 250 feet in diameter, which Fuller’s team engineered. Cambridge Seven designed the interior, which consisted of staggered platforms, described by Bakanowsky as “lily pads,” joined by escalators and stairs. Exhibits showcased items from a NASA lunar landing module and oversized works of contemporary art to Raggedy Ann dolls and mouse traps—all products of American creativity and ingenuity. An elevated monorail further animated the pavilion, bisecting the spherical space at the equator as it transported Expo visitors throughout the fairgrounds.

The other prominent multidisciplinary project Cambridge Seven tackled in the mid-1960s involved environmental design for the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) transit system. As Chermayeff notes, “We made some basic changes that had to do with the experience of the user, the people who use the system, riding the trains or the buses, walking through the stations. We developed guidelines and standards and, above all, a system of graphics and identity that unified the different subway stations and gave clarity to where you were and where you were going.” These changes included rebranding the transit system as the “T,” an idea borrowed from Stockholm, Sweden. “We concluded that the ‘T’ would work as a symbol for a lot of very good reasons. Intuitively, if you see the letter T, you can think of transportation, travel, transit, tube. . . so many words that conjure the notion of what it’s all about,” Chermayeff says. Geismar painstakingly created the black-and-white “T” logo, still ever present throughout the Boston region.

Likewise, a version of the “T”’s minimalist spider map remains in use today, coherently depicting individual locations within a larger, unified system. As Chermayeff explains, they color coded the subway lines, providing each line with a geographically derived identity. Thus, the former Harvard–Ashmont Line was renamed the Red Line, referencing Harvard’s signature color. The track running to Boston Harbor and northeast along the sea became the Blue Line, while the Green Line branched toward Olmstead’s Emerald Necklace southwest of Boston. “And Orange . . . well, I just didn’t know what else to do,” Chermayeff confesses. “It was a fourth color, and it made sense to combine with the others!”

Above ground, the colors simplified the user experience, signaling the stations’ affiliations. “As you walk down the street, if you see green and orange, you know that this station takes you to both Green and Orange Line trains. This means that the whole city, the skeleton of the city, becomes more legible,” Chermayeff notes. “Looking back on it,” he concludes with a grin, “in terms of the impact on millions of people over time, I think what we did there was pretty terrific.” That this overarching scheme for the MBTA endures today, nearly sixty years later, suggests that Chermayeff is indeed correct.

Moving into the 1970s, Cambridge Seven continued to garner attention, completing an array of work including museums, educational buildings, and mixed-use complexes, eventually winning the American Institute of Architecture’s prestigious Firm of the Year award in 1993. Chermayeff became known internationally as the foremost aquarium architect, leading significant projects throughout North America, Europe, and Asia. He also continued to make films, including the eleven-part, non-narrated Silent Safari series for Encyclopedia Brittanica that depicts rhinoceroses, lions, and other animals in their natural East African habitats. Chermayeff left Cambridge Seven in 1998 with two younger collaborators, Peter Sollogub and Bobby Poole, and he continues to practice design with Poole.

Throughout his career, Chermayeff, the “ambivalent architect,” has approached the built environment through a multidisciplinary lens, integrating design and visual culture to make useful, inviting, inspiring places for the public at large. Thinking about the profession today, he forecasts an even greater need for collaboration. “An architect is, almost by nature now, an expression of a collective will rather than an individual will,” Chermayeff asserts. “We learn from each other, and we learn by tackling and solving problems that matter. I like to think that in the next several years, we’ll find ways to address issues like housing and the environment more broadly, where instead of individualistic statements, design occurs through more bees building their bits of the hive, reinforcing each other to make urban places that are humane and rich.”

Ehao Wu Wins APA Economic Development Division Holzheimer Memorial Student Scholarship

First-year DDes student Ehao Wu has won the 2025 Holzheimer Memorial Student Scholarship for Economic Development Planning , awarded annually by the American Planning Association (APA), for his paper “Innovation Districts and Urban Economic Resilience: Kendall Square’s Sectoral Transformation,” written for Rachel Meltzer’s class, “Local Economic Development: Turning Theory into Practice.”

Named in memory of economic development visionary Dr. Terry Holzheimer, the scholarship includes a $500 award and will be presented at the APA National Planning Conference in Denver, Colorado, in late March. Wu’s paper will be published on the Economic Development Division (EDD) website and distributed electronically to EDD members in the News & Views newsletter.

Spring 2025 Update from Ann Forsyth, Chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design

Dear UPD Alumni,

I hope this note finds you well and enjoying the winter. As the 2024–2025 academic year progresses, Gund Hall is once again bustling with students after the winter break. With phase one of the Gund Hall façade renewal project now complete, we are already enjoying a more energy-efficient, comfortable, and accessible learning space.

I am delighted to share recent updates and news from the Department of Urban Planning and Design (UPD). There are many updates across our programs, faculty, exhibitions, and events.

Program Updates

We welcomed the second cohort of Master in Real Estate (MRE) students to the GSD. Nearly half of this year’s 38 MRE students hail from countries outside the United States, enriching the MRE program with diverse professional and global experiences. Read more about the program.

Faculty Updates

Over the past year, UPD has hosted a terrific set of lecturers and design critics, and we have welcomed several new regular faculty to our department:

- Rachel Weber, Professor of Urban Planning, joined the department in January 2025. As an urban planner, political economist, and economic geographer, Weber researches the relationship between finance and the built environment. She explores how cities’ deepening relationships with financial markets have changed how they budget, fund infrastructure, and manage their assets.

- Maurice Cox LF ’05, Emma Bloomberg Professor in Residence of Urban Planning and Design, joined the department in Fall 2024. Cox is an urban designer acclaimed for his ability to merge architecture, design, and politics in pursuit of design excellence and the equitable development of cities. Prior to joining the GSD faculty, Cox was Director of Planning and Development for the City of Detroit and Commissioner of Planning and Development for the City of Chicago, where he focused on the adaptive challenges facing contemporary urban revitalization.

- Magda Maaoui, Assistant Professor of Urban Planning, joined us in Fall 2024 after a year as visiting faculty. Maaoui explores the housing production cycle from start to finish as the consequence of regulation and policy, an act of design and construction, and a catalyst for neighborhood health and environmental outcomes.

- Dana McKinney White MArch ’17, MUP ’17, Assistant Professor of Urban Design, was appointed in 2023. McKinney White is a licensed architect and urban planner who is an outspoken advocate for social justice and equity through design. She develops innovative design solutions to benefit even the most vulnerable populations, including system-impacted communities, persons experiencing homelessness, and aging populations.

- Carole Voulgaris has been promoted to Associate Professor of Urban Planning. Her research investigates the factors influencing individual and household travel decisions within cities and examines how transportation planning institutions use this information to inform plans, policies, and infrastructure design.

Planning @ 100

In 2023, we celebrated a century since the Master in Landscape Architecture in City Planning degree was offered at the GSD, marking the inaugural Harvard degree with “city planning” in its title.

“While the first course in city planning at Harvard was offered in 1909, it was in 1923 when the degree Master in Landscape Architecture in City Planning was introduced in the School of Landscape Architecture. A separate Graduate School of City Planning was established in 1929, the first in the United States. In 1936, it became the Department of City and Regional Planning when the Graduate School of Design (GSD) was established.”

The Planning @ 100 exhibition in the Loeb Library highlighted Harvard’s pivotal role in shaping planning education and practice. I curated this exhibition along with Sophie Weston Chien MLA ’24, MUP ’24; Rebecca McDonald-Balfour MLA ’24, MUP ’24; and Naomi Andrea Robalino MUP ’23, with special thanks to Amna Pervaiz MUP ’23. We chronicled the program’s evolution, including key people, events, and activities, until the present day. I invite you to explore the exhibition’s webpage .

APA Denver

In the coming months, our department will share more news about the future of UPD and opportunities to connect with planners across the globe. Please join us for the APA Denver GSD Alumni Reception on March 30, 2025. I hope to see you there!

Wishing you all the best,

Ann Forsyth

Ruth and Frank Stanton Professor of Urban Planning

Chair, Department of Urban Planning and Design

Program Director, Master in Urban Planning

Department of Urban Planning and Design, Harvard GSD

PS: Follow the GSD’s alumni events page to discover events near you.

Visit the Department of Urban Planning and Design to learn more about programs.

When the Client is a Nation

Inside the Peabody Museum on a windy October day, leaders of the Sac and Fox Nation peered into the eyes of their ancestor, William Jones , the second Indigenous person to graduate from Harvard, in 1901. Posed in a cap and gown, Jones’s black-and-white photographs sit under a glass case beside a pair of beaded moccasins.

“He’s almost as good-looking as I am,” Principal Chief Randle Carter joked with Robert Williamson. Carter and Williamson had traveled to Harvard from Oklahoma, where Jones was born in 1871 and the tribe is based today.

The Sac and Fox are one of 574 Native tribes who operate as nations within a nation; they have the right to self-governance and maintain their own political systems . Williamson and Carter were invited to Harvard by Eric Henson, a lecturer in Urban Planning and Design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and a longstanding member of the Harvard Project on Indigenous Governance and Development , which helps Indigenous nations worldwide strengthen their governance systems. Henson’s Fall 2024 GSD course, “Native Nations and Contemporary Land Use”, brought together GSD students with representatives of the Sac and Fox—along with the tribe’s collaborator, a professional hockey team—to help the tribes meet their goals to regain sovereignty over their ancestral lands in Illinois.

“With a focus on land use, landback initiatives, and economic development opportunities,” writes Henson, “the course provides in-depth, hands-on exposure to how Native people are addressing these issues today.” Landback initiatives have been underway since the colonial era but only became widely known as such in the last few years. Part of Native nations’ work towards claiming their sovereignty, landback focuses on a number of initiatives, including acquiring land that was stolen from them throughout the process of colonization.

“If you’re building something new, or designing a park,” said Henson, explaining the importance of learning Indigenous history at a design school, “you have these steps you are supposed to check off: Did we do this review? Did we look for artifacts or archaeological dig sites? I’d like to see a degree of understanding beyond that. It’s not just a box to check off. You’re talking about real people who are victims of genocide and war and outright theft of their traditional territory. Taking a few minutes talking to a tribal leader before starting a design might open your eyes to the place in which you’re doing that work.”

For example, he says, in Bendigo, a town north of Melbourne, Australia, town leaders collaborated with the Dja Dja Wurrung , the Indigenous community, to incorporate Native design elements, revitalizing the town and attracting more investors. Henson noted that there are Native design elements in many buildings in Bendigo, which offers a model for others to follow.

This semester, students are working with two Indigenous Nations. Henson, a Chickasaw citizen, draws from his deep contacts with tribes around the US who have requested to work with him and his classes. The course Henson teaches at the Kennedy School , Nation Building II/Native Americans in the Twenty-First Century, offers collaborations with Indigenous Nations and now serves as a companion to the course at the GSD, with projects carrying over from one to the other. The course at the Kennedy School is cross-listed with the GSD, the Faculty of Arts and Science, the Graduate School of Education, and the Chan School of Public Health.

“With more education around Indigenous history, culture, and design, there could be tremendous collaboration between designers and Indigenous nations,” Henson argued, “with Indigenous design elements incorporated. In addition, non-Native communities that neighbor tribal lands have great opportunities, if they want to embrace them and work with tribes.” Not least of which, Henson explained, is the tribes’ access to federal funding and their role as major employers, particularly in rural areas.

This mutually beneficial relationship is what Rahul Mehrotra hoped for when he suggested a Native-focused GSD course to Henson in 2020, when Mehrotra was chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design. Henson collaborated with Philip DeLoria and Daniel D’Oca to design an interdisciplinary GSD class they called “Land Loss, Reclamation, and Stewardship.”

“In the context of discussions at the GSD on diverse ways of understanding history, and in the context of climate change,” said Mehrotra, “learning from traditional practices is very important. The relationship that Native Americans have to the land, and to nature more broadly, is sensitive, beautiful, poetic, and empathetic—and incredibly intelligent.”

GSD students’ work impacts the lived environment around the world, Mehrotra explained, and with more education about Indigenous people and their history, design students’ sensibilities would invariably shift.

“I wanted the Indigenous studies course to have history, design, and practice components,” said Mehrotra, “so that students would have a sense of what they can learn from history and traditional practices as they intersect with design.”

This past fall in Henson’s course, GSD students Cayden Abu-Arja (MArch I / MUP ’27) and Neady Oduor (MDes ’26) opted to work with Carter and Williamson to design a program to help them regain their ancestral lands, which the tribe determined was one of their primary goals.

“Our traditional lands,” Williamson explained, “are not in Oklahoma.”

For 12,000 years, the two tribes, then known as Sauk (now Sac), the Yellow Earth People, and Meswaki (Fox), the Red Earth People inhabited the area around Quebec, Montreal, and eastern New York state, but were forced southwest by the Iroquois, and then further west by the French. The two tribes banded together and moved to Illinois, establishing their summer village in Saukenuk, today known as Rock Island, along the Mississippi River. There, they planted 800 acres of corn, vegetables, and fruit to feed the almost 5,000 people in the well-organized community.

Abu-Arja and Oduor quoted tribal leader Black Hawk’s autobiography, in which he describes his memories of that place: “It was our garden (like the white people have near their big villages) which supplied us with strawberries, gooseberries, plums, apples, and nuts of different kinds, and its waters supplied us with fine fish, being situated in the rapids of the river.” Black Hawk recalled spending his childhood summers on the island, surounded by family.

In 1804, colonists tricked the Sac and Fox chief into signing a treaty that gave the land to Illinois, forcing the tribe off their summer grounds to the west of the Mississippi. By 1832, with the Sac and Fox people starving, Black Hawk led the community back to Saukenuk to plant their traditional summer crops.

“After years of encroachments from the US government,” said Williamson, “this was Black Hawk saying, ‘I want to go home.’” Instead, said Williamson, the Illinois militia “slaughtered women, children, and older men” over the course of more than three months, in what colonists called the Black Hawk War. The Sac and Fox were subsequently pushed further west again, this time to Oklahoma, where they live today and continue to fight for access to their ancestral lands.

Landback Initiatives & Innovative Collaborations

At the beginning of January, another tribe, the Prairie Band Potawatomi , were approved by the Illinois State House to receive a land transfer of 1,400 acres, which makes up Shabbona Lake State Park, named for Chief Shab-eh-nay. The government sold the land illegally in 1849, violating a treaty the Prairie Band had signed 20 years earlier. The Potawatomi have agreed to continue allowing public access to the park, which will be maintained by the state.

Tribes across the US have undertaken landback initiatives in different ways, from acquiring the land through private purchase to lobbying for it from state lands or through estate planning. For the Sac and Fox, a Nation with about 4,000 members, the goal is to follow the lead of the Potawatomi to reestablish their footing back in Illinois around the site of Saukenuk village. Today, Illinois maintains Black Hawk Historic Site on the tribe’s ancestral lands, with a statue of the warrior, a small museum that describes Saukenuk, and a 100-acre nature preserve. Williamson noted that, like many other Indigenous US tribes, their leaders’ names have been used for streets, towns, professional sports teams, and even army helicopters. They deserve to have access to their ancestral lands.

Joining Carter and Williamson on their trip to Illinois were representatives from the Blackhawks Hockey team, whose CEO, Danny Wirtz, has invited the nation to collaborate in ways the Sac and Fox choose. While many Indigenous advocates have argued for professional sports teams to change their name, Wirtz suggests that the collaborative work he and his team are doing with the Sac and Fox requires more authentically engaging with one another. The tribe voted to work with the hockey team and is prioritizing economic development, strategic planning (including landback initiatives), and language preservation projects.

“Our partnership with Black Hawks’ tribe, the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma,” says Sara Guderyahn, the Chicago Blackhawk’s Executive Director, “is centered around education and cultural preservation with the goal of supporting the Nation’s priorities for sovereignty. To that end, we are excited and optimistic that this project is an important step to explore opportunities for the Nation to reconnect with their original homelands in Illinois.”

GSD students Abu-Arja and Oduor began their work with the Sac and Fox by learning about the tribe’s history, including their forced migration through the US, Black Hawk’s leadership, and the Nation’s ancestral lands. The group’s visit to the Peabody Museum with Carter and Williamson highlighted the Sac and Fox’s most famous members: anthropologist William Jones, whose photos and writings they viewed alongside the leaders at the museum and in the archives, and football player Jim Thorpe, who won two Olympic gold medals in 1912.

“When you look at the record books,” said Chief Carter, “Thorpe was not a citizen of the US. Before 1924, Indian people were not citizens of the United States. The record should say he was a citizen of the Sac and Fox Nation.”

Henson led the group to visit a site on Harvard’s campus that brings Thorpe’s legacy back to contemporary material culture. At what’s now Clover Food Lab , the ceiling tiles that depict the early twentieth-century Harvard football league pennant flags include the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. When Jim Thorpe led Carlisle to defeat Harvard in 1911, the Indian School was cut from the league; Harvard never played them again. The Indian Industrial school was part of the US government’s attempt to erase Indigenous culture through the forced removal of thousands of children from their homes and families, under the motto “kill the Indian, save the Man.” When the tiles were uncovered on Massachusetts Avenue, right across from Harvard’s gates, in a 2016 renovation , they restored to the record in Cambridge the story of Jim Thorpe at Carlisle, before he went on to win Olympic gold medals.

The group’s visit to the site was part of a tour Henson led, which was originally designed by Jordan Clark, Executive Director of the Harvard University Native American Program (HUNAP) and a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Aquinnah. The tour makes visible the Indigenous histories that are often missed all around us.

For example, Henson pointed out a plaque on the side of Matthews Hall, commemorating the history of Harvard’s Indian College— founded by missionaries in the 1640s—whose bricks were eventually dismantled to build other Harvard structures. Henson pointed to a spot on the lawn beside Matthews Hall, where a 1990s archeological dig revealed pieces of the press used to print the Eliot Bible, written in Algonquin (a language of Indigenous tribes), the first Bible printed in the US, now held at the Houghton Library . Henson noted the plaque on the president’s house that names the enslaved people who laboured there, and the rusty pump in the center of the yard, which marks the water source from which Massachusett and other Indigenous people were cut off when settlers claimed the site.

Making Indigenous histories visible, highlighting how their stories predate colonization by thousands of years, as well as how they are irrevocably intertwined with Harvard’s history, helps to make tangible the ethos of the land acknowledgment that the GSD wrote in collaboration with HUNAP and reads at the beginning of every public event.

Strategies to Educate the Public and Regain Access to Saukenuk

After learning the histories of Indigenous nations in the east and midwest, Abu-Arja and Oduor focused on designing a program centered on “co-management” of the Black Hawk State Historic Site, which they say the Sac and Fox Nation “sees…as a way to connect with their ancestral homeland…and pass on traditions (some of which were lost when they were removed from their land).” The team outlined three goals: 1) creating storytelling opportunities so that people understand the “social and cultural significance of the Black Hawk State Historic Site” to the Sac and Fox Nation, 2) developing revenue streams, and 3) increasing collaboration with Illinois state.

They defined 15 different activities, from collaborating with the Sac and Fox to develop new exhibits at the existing historic site museum, to building clan houses for cultural activities, hosting riverside storytelling sessions and ceremonies, creating a gift shop, and “tailoring [the tribe’s existing language programs] to young students who visit the site.” They note that the Nation can turn to existing protections, for example, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which would support co-managing the cemetery where Black Hawk’s children are buried but remain unnamed on signage that commemorates settlers. As precedent for managing burial grounds, they cite Minnesota’s Indian Mounds Regional Park, which was developed around the gravesites of several tribal nations to protect the mounds and share their people’s histories. By increasing the public’s knowledge of and engagement with the Sac and Fox Nation, as well as collaborating with the state government, the Sac and Fox’s case for landback will become more visible—and therefore, more viable.

At the end of the semester, Abu-Arja and Oduor presented their proposals to the Sac and Fox Nation, who are moving ahead with their plans to develop the programs in Illinois, which they hope will bring them one step closer in their two-hundred-year battle, starting with their ancestor Black Hawk, to regain their lands.

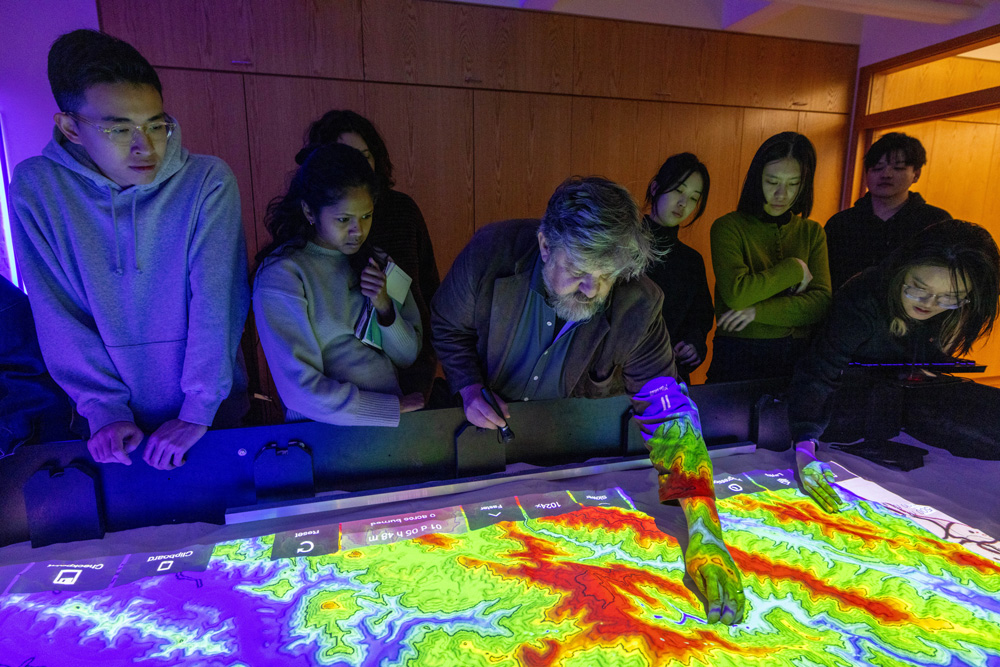

Landscape Architecture Students Explore Pioneering Climate Visualization Techniques to Inform Design

Droughts, floods, food shortages, species extinction—the impacts of climate change are physically tangible. Yet, the terms and data used to describe these predicted impacts often seem abstract. Richer visualization techniques offer great promise to communicate the consequences of climate change and thereby promote the adoption of strategies to preempt these effects. This semester at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), master of landscape architecture (MLA) students are exploring two such innovative modeling approaches: a framework for understanding spatial impacts of climate strategies over time, and a modern sand table that supports real-time simulations.

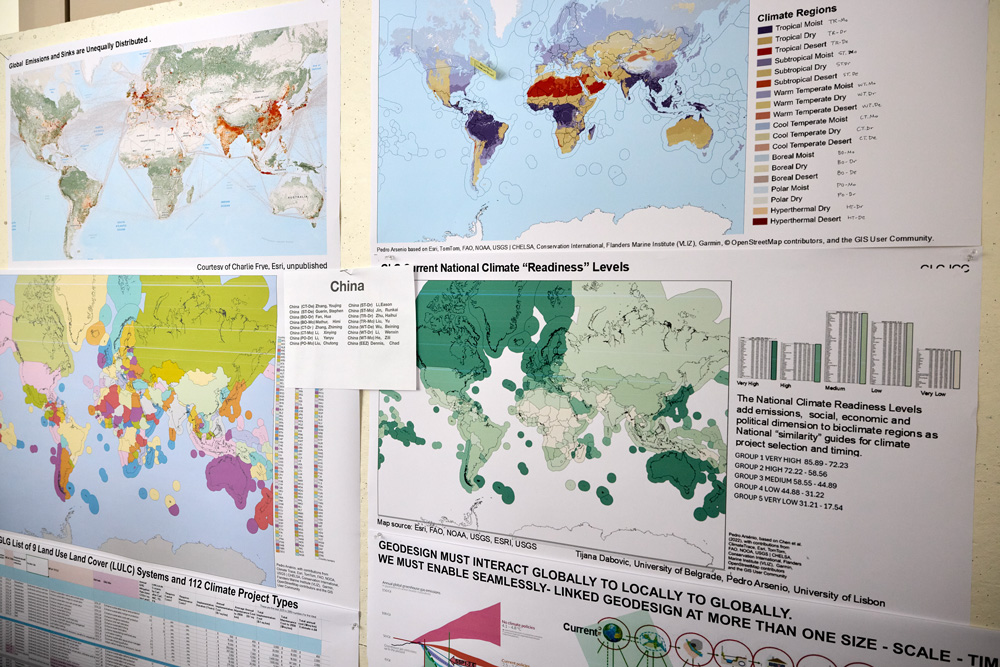

Since the 1960s, Carl Steinitz—Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Landscape Architecture and Planning Emeritus—has been contemplating land-use change as a designed process. As part of the Harvard Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis, Steinitz began using geographical information system (GIS) maps to evaluate the impacts on a given area of variables such as population growth and migration, financial influx, and environmental conservation. In the ensuing years, Steinitz developed a framework for “geodesign,” a term coined to describe design in a space linked to a geographic coordinate system with its accompanying specificities. Today the International Geodesign Collaboration (IGC), which Steinitz helped found, defines geodesign as “a collaborative approach [that] uses GIS-based analytic and design tools to explore alternative future scenarios in response to global problems.” When first exploring this problem five decades ago, Steinitz initiated his geodesign work with a two-square-mile geographical region; recently, he expanded this scope to the global scale.

In 2022, in conjunction with the company Esri —a global leader in GIS software, location intelligence, and digital mapping, cofounded by Jack Dangermond (MLA ’69)—Steinitz and additional collaborators began work on the ICG Global to Local to Global (GLG) Climate Mitigation Project, building the technology to facilitate geodesign for the purpose of climate change mitigation.1 Steinitz introduced the project to MLA Core IV students (those engaged in their final studio of the core sequence), characterizing mitigation as “a multi-jurisdiction, multi-scalar geodesign problem. Climate change,” he explained, “is a global existential phenomenon, and all nations must act in collaboration if climate mitigation is to succeed. Guided by climate science, this requires looking and thinking ahead in time, globally to locally to globally, and planning now to act now for the future of everyone.”

While multinational agreement and a global oversight of planning, negotiation, and implementation does not yet exist, Steinitz and colleagues view the GLG Climate Mitigation Project, a protocol to facilitate this process, as necessary infrastructure for future climate action. Building from a geodesign framework published in 2012, Steinitz has created tools to identify mitigation strategies to optimize impact by considering the date of initiation (for example, 2025, 2050, or 2080), execution and maintenance costs, alterations in climate (temperature and aridity), and additional variables across a span of decades. Focusing on changes in land use, the goal is to lower carbon emissions below zero, ideally (if perhaps improbably) returning atmospheric measurements to pre-Industrial Revolution levels. In short, the GLG Climate Mitigation Project offers a preview of, and guidance on how, mitigation-related decisions can affect our future.

Following his explanation of the project, Steinitz walked the MLA Core IV students through a tutorial on how to use it. This exercise served a double purpose, providing a test run for the tools themselves while preparing students for their upcoming semester-long studio “The Near Future City,” focused on Boston’s Charlestown neighborhood. Lorena Bello Gómez, GSD design critic in landscape architecture and lead instructor of the studio, sees the GLG Climate Mitigation Project as a climate action framework students can use to determine suitable mitigation strategies for the studio’s site. These include strategies such as enhanced wetland restoration, neighborhood energy retrofits, infrastructural recalibration, urban canopy growth, and sustainable wastewater management.

Charlestown sits within a warming climatic region that, in years to come, will face increasing challenges around already-problematic issues of inland flooding, salt-water inundation, and heat island effect. Highlighting why climatic shifts matter, Steinitz asked students about appropriate trees to plant at this location today. “Where are you going to look [for precedents]—Charlestown or South Carolina?” Considering that the latter approximates Charlestown’s expected climatic region in 2050, “I’d look to South Carolina if I were you,” Steinitz declared, “especially if the trees take thirty years to grow,” as many species do. This point, while seemingly simple, underscores an important reality: today’s designs must take future conditions and long-term repercussions into account.

For the students, then, the GLG Climate Mitigation Project offers mitigation strategies for Boston’s climatic region that can be adapted for maximum impact in Charlestown. Once students have a particular strategy in mind, they can explore a different visualization technique—the Simtable . Invented by Stephen Guerin, affiliated with Harvard’s Visualization Research and Teaching Laboratory , the Simtable is a high-tech sand table that uses GIS data and computational modeling to explore complex phenomena, such as wildfires or chemical plumes, that involve people, places, and things interacting over time.

To demonstrate the Simtable’s interactive and projective capabilities, Guerin projected a topographic map of a fire-threatened Los Angeles region onto the sand. He asked the students to shape the sand by hand, following the map’s contours, building mountains and excavating valleys. Onto this modeled surface Guerin then projected satellite imagery of the area. Setting parameters such as time and weather conditions, he began testing scenarios for the fire’s progression and containment, using a laser pointer to select and implement different tactics. For example, how does bulldozing a trench from point A to point B impact the fire’s spread? What about sending resources to points C and D simultaneously? Or staggering them, while designating certain routes for human evacuation? The interactive simulations offer immediate feedback with minimal effort, facilitating a rapid iterative process for exploring, adjusting, and assessing interventions. Guerin’s ingenious tool has been employed numerous times during real-life emergencies, including the Los Angeles fires in January 2025.

For GSD landscape architecture faculty, the Simtable offers phenomenal possibilities to inform design. Bello envisions the table as a tool that could allow architects to “move back and forth between design and performance, exploring parameters in a more fluid iterative process” than afforded by conventional physical modeling techniques, which are notoriously labor and time intensive. Furthermore, Simtable’s interactive nature could enhance community participation in climate adaptation and mitigation planning, the success of which often relies on robust social engagement. As Bello notes, instead of showing data on a stationary screen, “you are projecting data onto [a tangible representation of] the territory, empowering people to construct that territory, which empathetically puts them in mind to act.”