Julia Thayne on the Challenges of Urban Sustainability

Julia Thayne , Loeb Fellow 2026 and Founding Partner of Twoº & Rising , recently delivered the keynote lecture at the Harvard Business School’s Climate Symposium , where she spoke about cities as catalysts for climate action. Her previous work at climate NGO Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI), the Los Angeles Mayor’s Office, and global company Siemens focused on how first-of-a-kind sustainable projects create tipping points for change at scale. Now, as a Loeb Fellow at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), she is applying that experience to research how cities meet their sustainability targets, while adapting to climate change. We met in Gund Hall to talk about her keynote and the work she’s undertaking at the GSD this year, including a new research project on the environmental and social impacts of hyperscale data centers in the U.S.

What is your research here at Harvard, as a Loeb Fellow, focused on?

In general, I’m looking at how cities are meeting their sustainability targets, or not, what that teaches us about where we need to focus moving forward, and how they’re also starting to incorporate more action around adaptation and resilience.

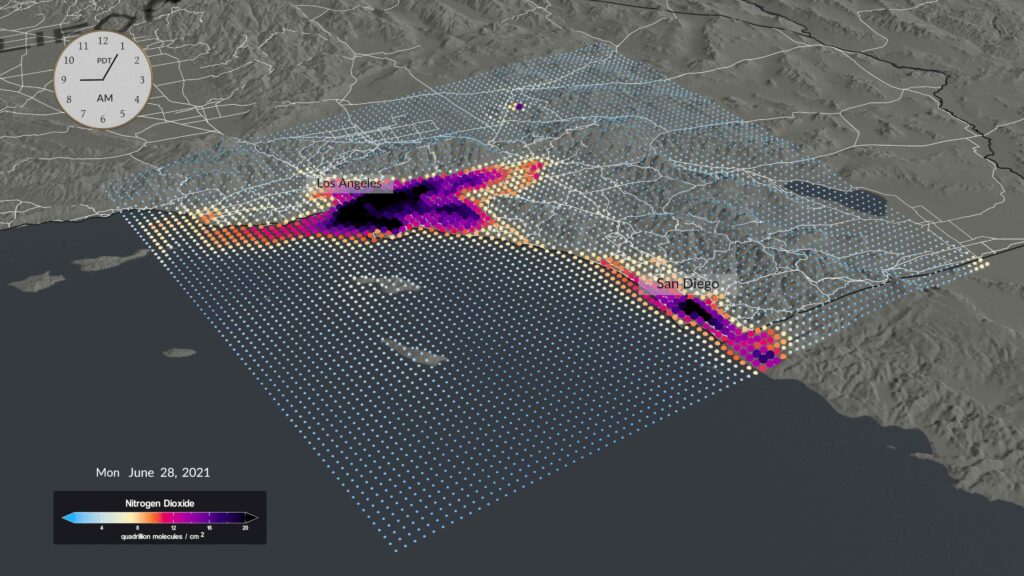

Like many others in climate, though, I’m also taking on a new research project on data centers in the U.S. They already consume a large amount of energy, and are projected to consume even more (in some states as much as 39 percent of total power). They’re polarizing in terms of their impacts. The research I’ve seen so far at Harvard has primarily been about data centers’ power consumption: how do you reduce it, what impacts does it have on investments in the grid, and will the public have to bear the costs of these upgrades. There are some excellent papers out on these topics by experts at Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and Harvard Law School, for example.

Along with Robert G. Stone Professor of Sociology Jason Beckfield, and Harvard College undergraduates Brady McNamara, Hailey Akey, and Julie Lopez, and with the support of a Salata Institute Seed Grant , I’ve taken on a research project from a slightly different angle: how do you optimize the environmental and social impacts of future hyperscale data centers in the U.S. that are being built near communities. Our goal is educate people about the impacts, give policy makers and communities ways to shape them, and ultimately affect how these data centers roll out so that they do have benefits.

Fortunately, as I’ve started on this research, I’ve also found the incredible GSD faculty and alumni who’ve been working on this topic for years, like Marina Otero and Tom Oslund. Already, we’ve been discussing how their landscape and architecture designs and practice are shaping what’s being built inside and outside the U.S.

Many of these centers are being constructed right now. How will you intervene in that system?

Remarkably, there are five companies who are primarily responsible for somewhere around one third of new large-scale data center construction. Five. If you can affect the way they think about data center siting, design, community engagements, and impacts, you can affect one third of what’s being built, which translates to hundreds of billions of dollars of investment. That’s pretty wild.

While the deliverables for our research grant are to create primers for key stakeholders, like developers, community groups, and policymakers, to inform actions that could optimize data center development, our ambition is to collaborate with the many others—at Harvard and beyond—who are trying to make sure that the best decisions possible are made around how data centers get built in our country. The development process is remarkably similar company-to-company. A real estate site selection team chooses sites based on power availability and land prices. The engineers help dictate the data center building design based on server needs, power, cooling, and time to construction. Then a team of architects, landscape architects, and engineers collaborate to optimize the design before—or sometimes as—construction is happening.

This is where my experiences in local government, huge tech companies, and research non-profits are coming in handy. I’ve written local policy that helps shape where things get built. I’ve managed tech projects and worked alongside engineers and technologists (usually as the only economist and urban designer in the room). My job at RMI was to think about where the intervention points were for changing systems. For example, how do you pinpoint the change that needs to happen that’ll affect not just one development, but many? So, in a strange way I’ve been preparing for this moment for my whole career, even though I didn’t know it would come.

In some ways, it’s a deeply personal ambition. My family lives in a small city that’s currently grappling with how data center development might affect their local economy and quality of life. In fact, my mom has been a very valuable primary source of information around data center development, sending me local news articles that are guiding some of the ways we’re doing our research! And my niece and nephew, ages 7 and 1, are who I do the work for, always.

Your keynote for the Harvard Business School’s Climate Symposium focused on the work you’ve done across your career on cities?

Exactly. The Harvard Business School (HBS) student groups organizing this year’s Climate Symposium wanted a nontraditional keynote to kick-off the event—somebody with a different perspective than the one they’re normally taught or exposed to at HBS. They gave me a broad topic: “Cities as Catalysts to Climate Action.” I used it as an opportunity to look at why cities are so important to climate action, what they’re doing, and how that has played out (well and poorly) in my own experiences in LA.

Cities are essential to climate action, because they’re the problem—and also hold the keys to the solution. Cities are responsible for roughly 70 percent of the world’s CO2 and methane emissions. They are where people live, work, and spend money. They also bear the brunt of climate change. So, in many ways, cities are both forced and choose to act on mitigation (how you reduce the impacts of human life on climate change) and on adaptation (how you adapt to the ways our climate is changing).

You see that everywhere, from Mexico City, where they’ve greatly expanded their bike and bus rapid transit networks to enhance road safety and give people affordable mobility, to Jakarta, where 40 percent of the city is below sea level and 33 million people are figuring out ways to continue living in the region.

You also see it in LA, where I’ve been living and working for the past 10 years.

What’s happening in LA that makes it different from other cities?

LA was part of the first wave of cities setting ambitious targets around carbon reduction: 50 percent emissions reduction by 2025, zero carbon by 2050. It’s hard to underscore enough that when those targets were set, we had no idea if we could achieve them! I mean, we had plans and models showing how we might achieve them, but as anyone who’s worked in local government knows, plans are very different than reality.

What’s noteworthy is that by 2022, LA had reduced emissions by 20 to 30 percent off the 2025 target, yes, but still—when you think about how hard we make sustainability sound (and how hard it is in practice), it’s pretty impressive. What’s even more impressive is that LA was only 1 percent off the target they set for their own municipal operations. That means what the local government could directly control, they were able to measure and manage. And what’s most impressive is that LA’s economy grew over that time. So, economic growth and environmental harm were essentially de-coupled.

Where was LA not able to meet its targets, and how does that reflect what other cities have done?

Cities generally do five things on climate action. They change where their electricity comes from by incorporating more renewable sources of energy. They reduce the amount of energy they consume, especially in buildings. They shift people and things to more sustainable modes of transportation, like public transit or zero-emissions trucks. They try to reduce waste by not creating it in the first place or re-using it. And, increasingly, they’re adapting to life with different weather conditions.

LA did really well on increasing the amount of renewables in their electricity mix, mainly by investing in big renewable infrastructure projects in and out of the state and changing up how people can buy renewable energy. LA also benefits from (right now) a mild climate where energy efficiency in buildings is easier. The city owns its own port and airports, too, so it was able to control more effectively emissions and pollution from those sources (though they’re definitely still not zero).

They did not do well on people’s mobility, though, or on waste. Some people might chalk that up to bad policy and politics or to something abstract, like “the difficulty of behavioral change,” but I think you have to look deeper. Historical decisions on land use, the lack of readily available and attractive mobility options, inadequate systems and information and accountability about waste, and LA’s importance as both industrial and urban centers – these are critical aspects of LA’s climate story, and they have to be considered when you’re thinking about how to take action on a topic as interdisciplinary and interconnected as climate.

What is your firm, Twoº & Rising, doing to help LA and other cities course correct on climate action?

My business partner and I started Twoº & Rising almost two years ago. We wanted to work with governments, companies, start-ups, investors, and organizations to accelerate the deployment of cleantech solutions in the U.S. “Twoº” is a reference to the Paris Agreement and the goal to keep global warming to 2 degrees by 2030.

Our work in LA specifically has been a lot about mobility, and this idea of giving people mobility options so that they don’t have to rely on cars—and also about adaptation and resilience, a huge and growing topic in the region.

LA is trying to use a series of upcoming global sporting events, like the 2028 Olympic & Paralympic Games, as tipping points for Angelenos to experience getting around the region without their own cars. We’re trying to capitalize on that moment by teaming up with local transportation agencies, as well as foreign start-ups and companies, who can offer high-quality, more affordable, safer ways to experience the city without its legendary traffic.

Similarly, my business partner and I both were temporarily by the LA wildfires in January (him by Eaton, me by Palisades), and are passionate about helping to find solutions to prevent them and to be resilient if and when they do happen. We worked on a project around providing grid resilience during public safety power shut-offs.

What do you hope students here at the GSD would think about in terms of sustainability?

I’ve explicitly devoted my career to climate. At the beginning, I don’t know that’s what I was doing, but now when I sit back, I realize it’s my calling. For some of you, that’ll also be your calling; for others, it’ll be something else. But whether you’re a “housing” person or a “public health” person or a “women’s rights” person or an “economic development” person, I hope you know that you also are, or can also be, a “climate” person. What you’re doing is inextricably linked to the climate and context it’s in, just as what I’m doing on climate is also inextricably linked to housing, public health, social justice, and economic growth or decline. If we can be mindful and intentional about that, we can stop considering these topics as trade-offs and start realizing just how supportive they are of each other.

A New Life Offered

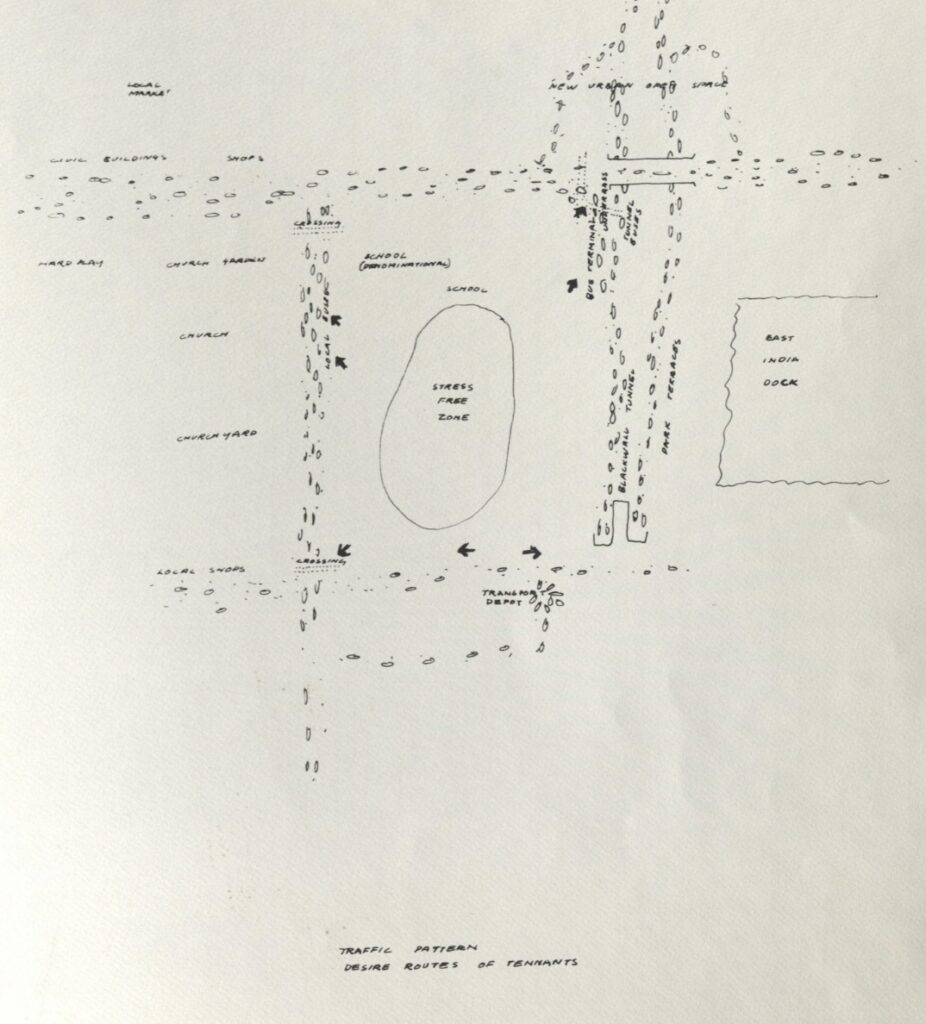

In 1970, Peter Smithson made the lofty promise that, at Robin Hood Gardens , the social housing complex he and his wife, Alison, designed, “you’ll be able to smell, feel, and experience the new life that’s being offered .” Two years later, the complex was complete, spanning two city blocks, with so-called “streets in the sky” that gave residents access to community, expansive views, and sunlit apartments—at least, that was the hope.

The detailed documentation the pair made of the site, with early sketches and photographs, as well as drawings and plans made throughout the design and construction process, can be viewed in the Frances Loeb Library’s Smithson Collection , the only publicly-accessible repository of the couples’ life work. Selections from the collection have been utilized for a wide range of scholarship activities, from books to exhibitions, including, last fall at the GSD, “Towards a Newer Brutalism: Solar Pavilions, Appliance Houses, and Other Topologies of Contemporary Life,” curated by Emmett Zeifman, a former GSD faculty member. Zeifman writes that the Smithsons understood new brutalism as “an ethic, not a style,” and hoped to “meet the changing needs and desires of postwar society through an architecture that directly expressed the material conditions of its time.”

In addition to offering a historical framework for understanding architecture today, the Smithson collection holds never-before-published drawings, photographs, sketches, and ephemera that bear testimony to more than fifty years of their vocation, including their philosophy of seamlessly integrating family life with work. There’s a landscape design by their twelve year old daughter, Soltana, for example, and childrens’ book manuscripts the couple co-wrote, along with pedagogical materials about the historical significance of Christmas imagery. “Innocent imagination, children’s books, and the responsibility of the architect,” writes M. Christine Boyer in Not Quite Architecture: Writing Around Alison and Peter Smithson , which draws from the library’s collection, “are continuously intermeshed in the Smithson’s writings…”

The Smithsons’ utopian design of Robin Hood Gardens, with its central hill created for children’s play, protected by a building made to support families in community, ended in controversy. While some residents advocated for the rich sense of connection facilitated by the “streets in the sky,” others argued that they became ideal tucked-away passages for crime. After decades of neglect, the dilapidated building was demolished starting in 2017, with the final portion completed in March of this year, though the V&A Museum preserved a small portion for its collection.

The Smithsons’ legacy, however, and their dreams of the benefits of social housing, helped propel forward the conversation around how to best ensure safe, affordable housing for all. The GSD, in partnership with the Joint Center for Housing Studies , has long addressed issues around social housing, expanding affordable housing access in the face of the climate crisis, and centering care in housing—some of the same threads of thought that led the Smithsons to build the iconic, if ultimately flawed, Robin Hood Gardens.

How a Collaboration Between Design and Real Estate Advances Equity in Mumbai

Students in Rahul Mehrotra’s “Extreme Urbanism Mumbai” Graduate School of Design (GSD) Spring 2025 option studio faced a challenge that was intended to take them “completely outside their comfort level,” said Mehrotra. “We set a wicked problem that exposes them to an unfolding of interconnected issues.”

Mumbai, set on a peninsula on the northwest coast of India, is one of the largest and densest cities in the world, with a population of about 21.3 million residents and more than 36,200 people per square kilometer—most of whom face a stark housing crisis. Approximately 57 percent of Mumbai’s population lives in informal homes, many of whom work in nearby housing complexes where they’re employed by the upper-class residents. Most of the students in the studio had never been exposed to what Mehrotra describes as “extreme conditions, in terms of density, poverty, and the juxtaposition of different worlds in the same space.”

“Mumbai is like nothing I’d ever seen before,” said Enrique Lozano (MAUD ’26), who had previously traveled to other parts of India. “There’s no designed urban form; skyscrapers are scattered throughout the city. It’s on a former wetland, so there are issues with water, one of my research areas.”

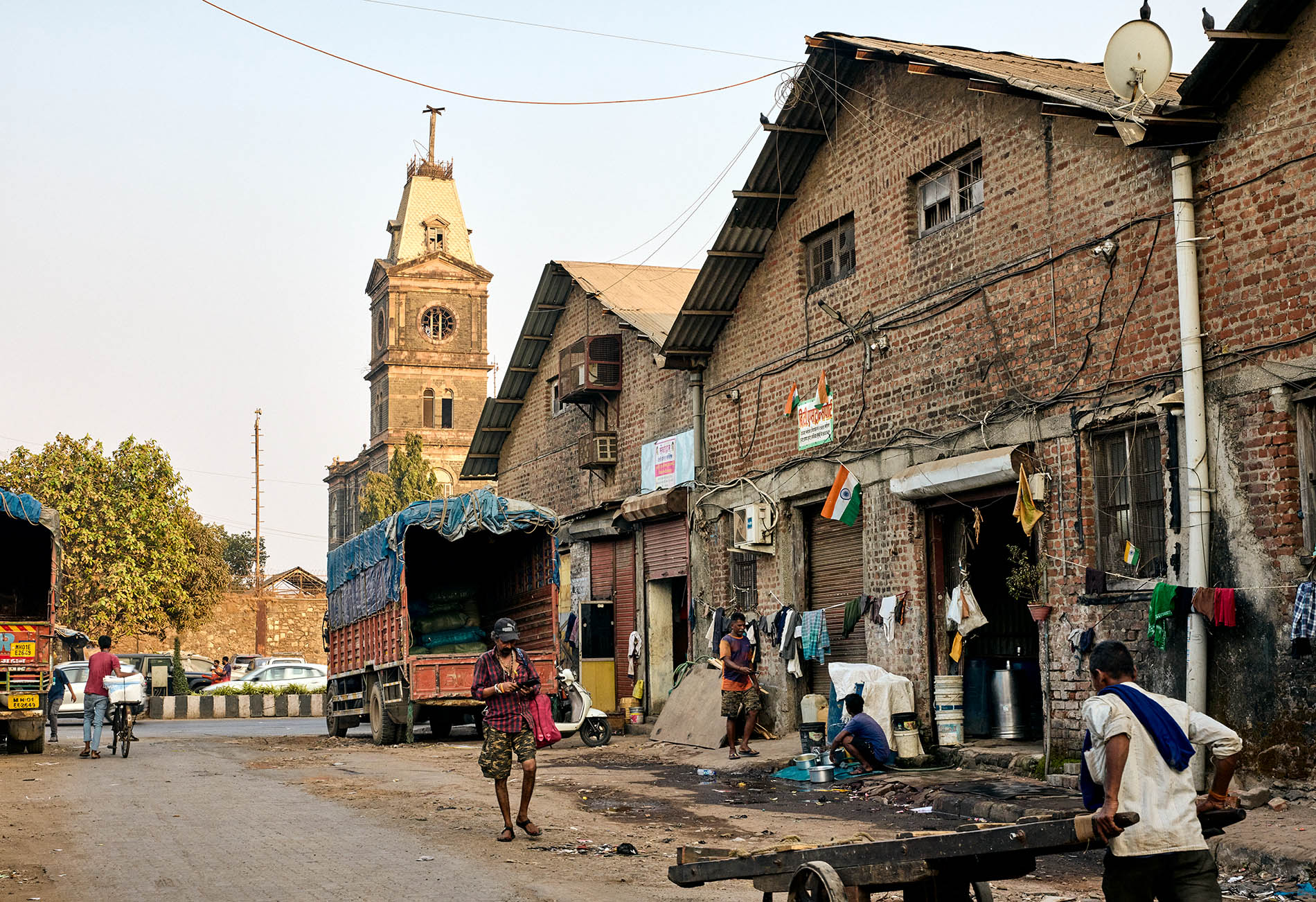

He and his classmates were introduced to Mumbai’s coastal Elphinstone Estate neighborhood and a site owned by the Port Authoritiy of Mumbai that includes 40 acres of warehouses as well as iron and steel shipping offices, bounded on one side by a rail line and on the other by the harbor and P D’Mello Road, a major city street. “The Eastern Waterfront will be one of the city’s most contested land parcels to be opened for urban development in the next few years,” writes Mehrotra. “It plays a catalytic role in connecting the city back to the metropolitan hinterland….” The 900 or so people who work in this area and live in sidewalk tenements stand to be displaced once development progresses.

Elphinstone Estate — the site of the studio

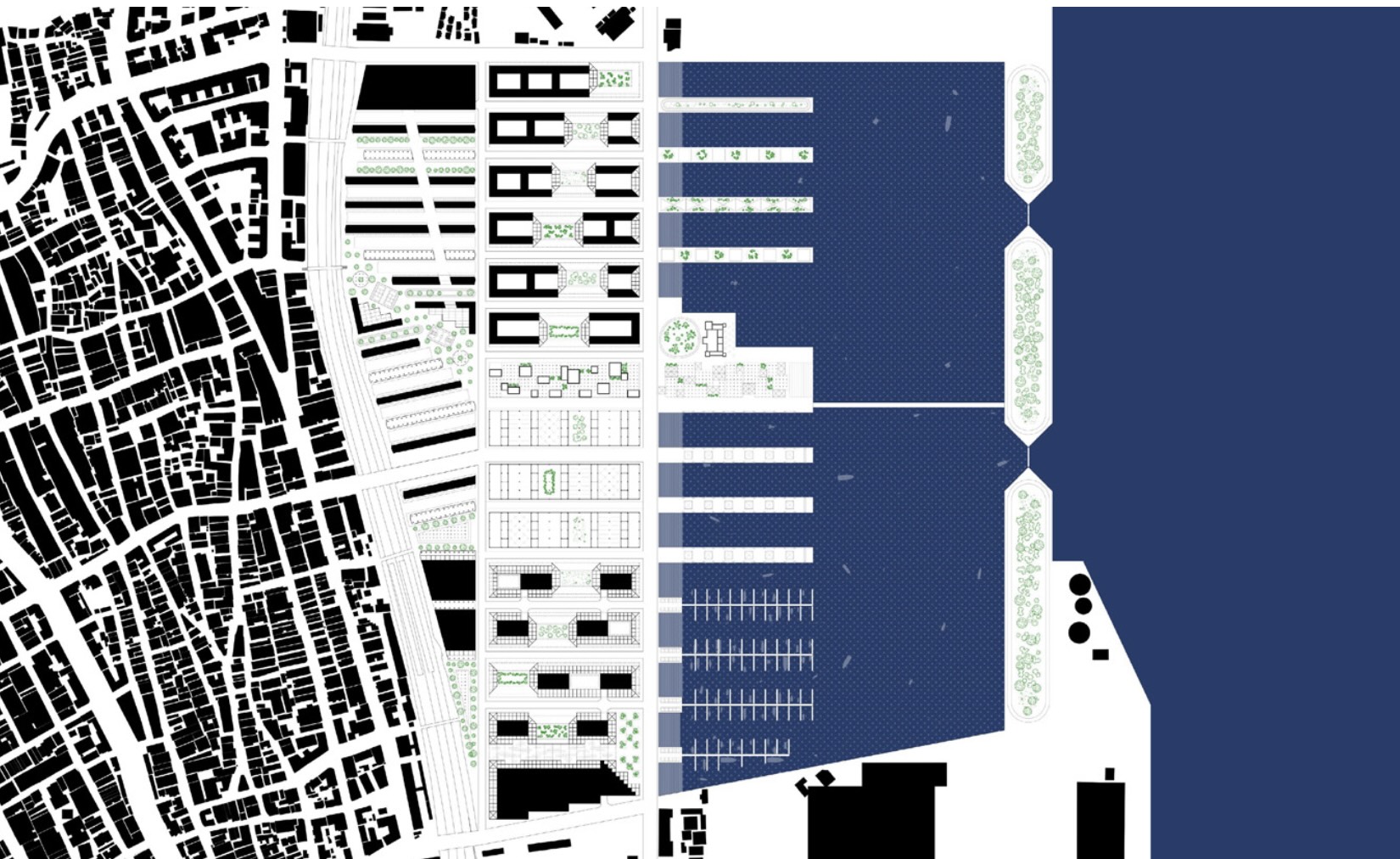

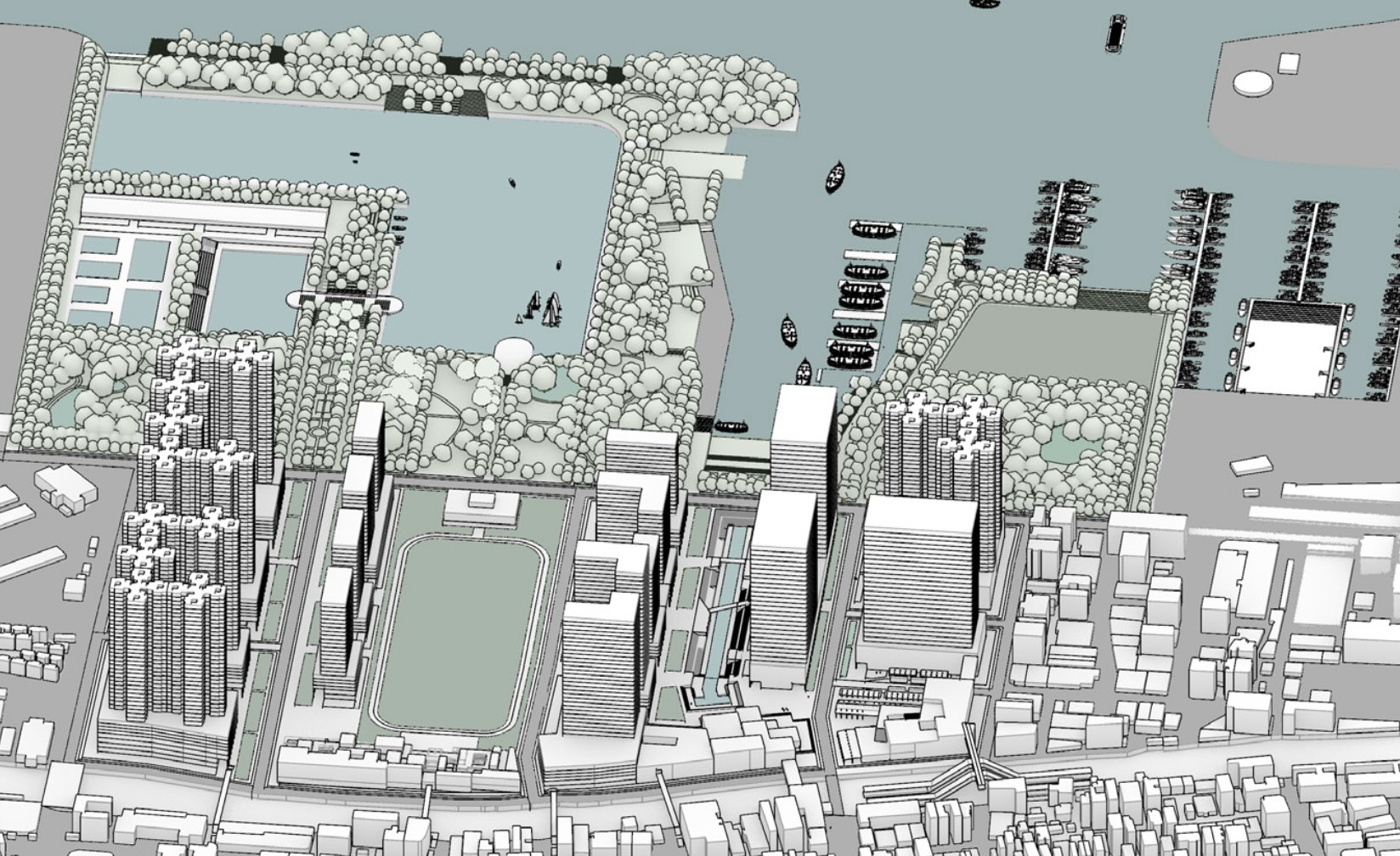

Students were tasked with working at three scales: regional, district (the “superblock”), and site (urban development policy). Rather than displacing workers whose lives are strongly rooted in the neighborhood, students were asked to invent schemes that would newly house those 900 families in tenements by “cross-subsidizing from market-value housing.” The studio offered a counterpoint to the government’s designation of the site as a commercial district. Students’ proposals served what Mehrotra terms in reference to his research, “instruments of advocacy,” creating a way to keep the city’s most vulnerable residents where they have always lived, while also offering needed market-value homes.

This studio differs from many others at the GSD, in that it involves collaboration between the studio and a Master in Real Estate course titled “The Development Project.” Jerold Kayden, Frank Backus Williams Professor of Urban Planning and Design and founding director of the Master in Real Estate Program, and Mehrotra brainstormed about the idea of such a collaboration and launched the idea in spring 2024. David Hamilton, a real estate faculty member at the GSD, co-instructed this year’s version in the spring 2025 semester.

“I think of real estate as the physical vessel in which people live, work, and play,” Kayden explained. “And if we can apply our multidisciplinary skills and knowledge to shape real estate in ways that create a more productive, sustainable, equitable, and pleasing world, then I can’t think of a more noble cause than that.”

The magic of the combined studio and real estate class, as Kayden, Mehrotra, and Hamilton saw it, was that students from the two programs would be interdependent and could only solve the on-site housing challenges by working together. “The real estate students couldn’t own the problem because the designers didn’t design it in a way that would work in terms of real estate sense,” said Mehrotra. “And the designers couldn’t think of the design unless the real estate folks came up with a model of financing for that cross-subsidy.”

Hamilton concurred that the studio set up a collaborative tension that replicated real-world challenges: “We can imagine a path that gets us from having bright ideas and a beautiful piece of land, to a proposed future that’s both appealing and realistic enough to attract investment capital to be built. Then, we get to what we call stabilization, where the new neighborhood is working physically and financially in a sustainable way. Getting there involves a million different variables, from government action and public subsidies, to the needs of the market and investors and other financial considerations.”

Lozano saw the benefits of designing in Mumbai, where “the street is an even playing ground. Everybody takes the metro, walks the Plaza, buys street food in the markets.” At the same time, like most collaborators, his group had their share of challenges as they moved through the design process. “The entire studio was a negotiation between the students—of judging our values and understanding that the real estate students want to make a return on investment, but the subversion is the social mission, and the designers had to convince them that social space is an asset.”

He described a beautiful 19th-century clock tower on the Elphinstone site, which one of his real estate group members wanted to demolish, and how they negotiated the “iterative design process” and “pushed against the blank slate idea.” They kept the clock tower, which they saw as a cultural asset, and “turned it into an incredible public amenity with restrooms, civic spaces, and movie screenings. It’s an anchor and memory of the site itself, with the maritime history and labor organizing that occurred there.” Through the collaborative process, building trust by drawing and talking through their design plans, the design students developed a final project of which they’re proud.

“As we become surrounded by the madness and complexities of the world we inhabit,” said Mehrotra, “it’s important to have multiple perspectives on the same problem, and to synthesize those multiple perspectives into a proposition.”

The final review mirrored the lively discourse the students experienced all semester, as critics discussed the merits of each proposal and the possibilities for the Elphinstone Estate. Sujata Saunik, Chief Secretary of the Government of Maharashtra, participated throughout the final review and helped bring to the conversation a sense of Mumbai’s realities. As the student groups together advocated for shared public access to the site and investing in dignified housing for people living in tenements, they presented to the government a more equitable approach to developing a site that’s unique as well as profitable.

“It’s not the solution,” said Mehrotra, “but it’s a conversation changer.”

Student Propositions

Summer Reading 2025: Design Books by GSD Faculty and Alumni

Whether you plan to read in the summer sunshine or an air-conditioned lounge, these recent books by Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) faculty and alumni conjure environments from the semi-arid Mezquital Valley to the frozen Arctic tundra.

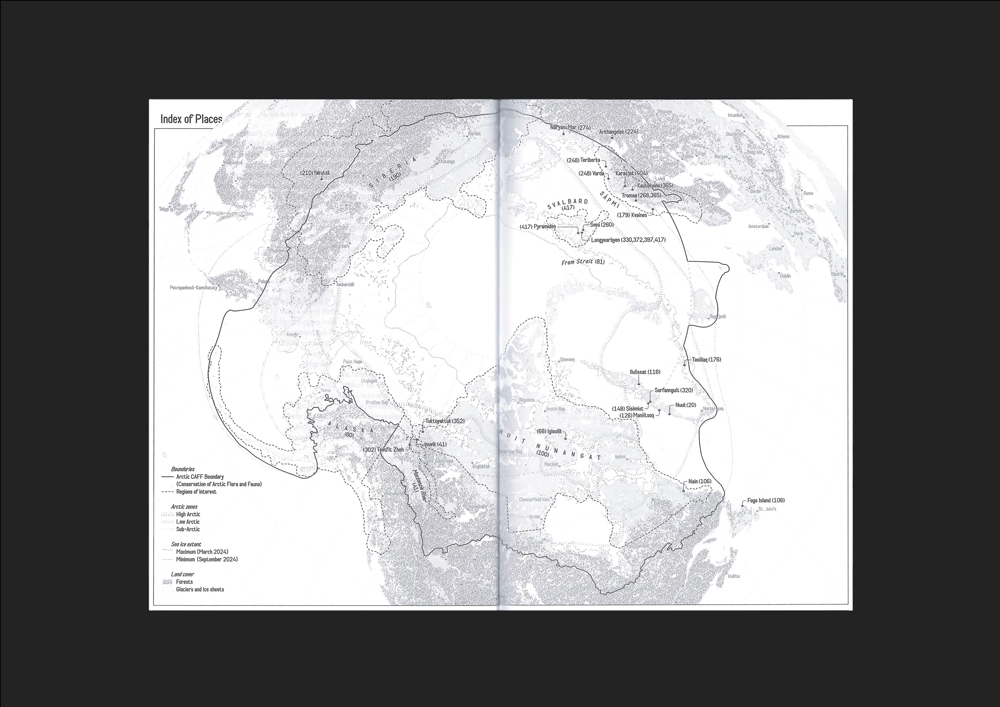

Arctic Practices: Design for a Changing World (Actar, 2025), edited by GSD lecturer in landscape architecture Bert De Jonghe (MDes ’21, DDes ’25) and Elise Misao Hunchuck, confronts two issues critical for Arctic lands: the climate crisis and the need for anticolonial reconciliation. Gathering texts by authors in the fields of design, education, and the arts, the collection offers diverse perspectives on current and future design interventions, all grounded within the Arctic’s distinct environmental and historical context.

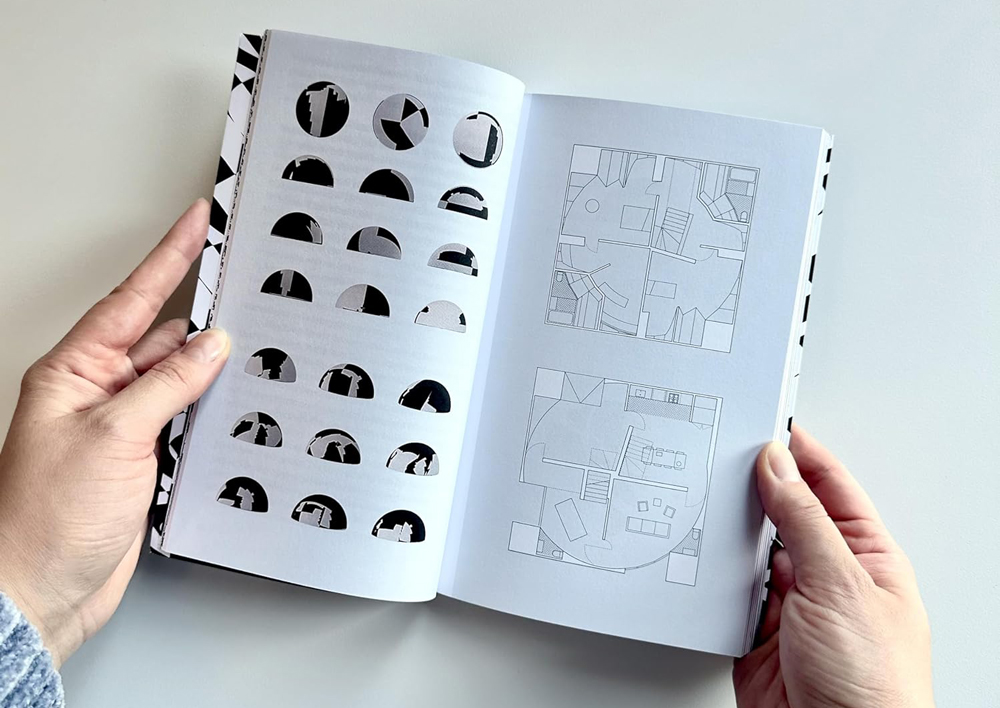

Design for Construction: Tectonic Imagination in Contemporary Architecture (Routledge, 2025), by Eric Höweler, professor of architecture and director of the Master of Architecture I program, bridges conceptual thinking and practical building techniques. The book delves into topics such as materials research and construction sequencing, dissecting projects by leading practitioners (including GSD-affiliates Barkow Leibinger, Johnston Marklee, MASS Design, NADAA, and others) as illustrative examples. As the discipline contends with its ecological and social impacts, re-engaging with design and building offers an opportunity for architects to assert agency while working toward a better future.

Drifting Symmetries: Projects, Provocations, and Other Enduring Models (Park Books, 2025), by Marion Weiss and Michael Manfredi, design critic in urban planning and design, features projects by the New York City–based architecture practice Weiss/Manfredi. Alongside the firm’s work—which is characterized by a multidisciplinary approach that melds architecture, landscape, and infrastructure—the book presents commentary from leading architects such as Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture Sarah Whiting, John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization Rahul Mehrota, Hashim Sarkis (MArch ’89, PhD ’95), Nader Tehrani (MAUD ’91), and Meejin Yoon (MAUD ’97), among others.

With the recent publication Hideo Sasaki: A Legacy of Collaborative Design, author Richard Galehouse (MCP ’61)—first Sasaki’s student at the GSD and later his business partner—traces the early development of Sasaki’s professional practice in the 1960s and 1970s. Through selected case studies Galehouse illustrates the legacy of design collaboration that Sasaki endowed to his professional practice—Sasaki —as it lives on today. In a distinguishing feature of the book, Sasaki speaks directly to the reader through excerpts from an interview conducted five years after his retirement.

All book proceeds support the Hideo Sasaki Foundation’s mission of equity in design.

Inside Architecture: A Design Journal (Balcony Press, 2025) by Scott Johnson (MArch ’75), FAIA, is structured as a personal and professional retrospective, offering a glimpse into the creative process of one of Los Angeles’s most accomplished architects. Combining candid narrative (including thoughts on his student years at the GSD), project case studies, and design commentary, Johnson reflects on the buildings, cities, and ideas that have shaped his decades-long career as the design partner and cofounder of the firm Johnson Fain.

Gareth Doherty (DDes ’10), associate professor of landscape architecture and affiliate of the Department of African and African American Studies, recently published Landscape Fieldwork: How Engaging the World Can Change Design (University of Virginia Press, 2025). This book challenges the discipline’s long-standing focus on the Global North and its current reliance on digital and technological solutions, offering tools for practitioners to engage more deeply with multidimensional, diverse landscapes and the communities that create, live in, and use them.

Landscape Is . . . !: Essays on the Meaning of Landscape (Routledge, 2025) explores various meanings of landscape as a discipline, profession, and medium. Edited by Gareth Doherty (DDes ’10), associate professor of landscape architecture and affiliate of the Department of African and African American Studies; and Charles Waldheim, John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture and co-director of the Master in Design Studies program, this collection is a companion volume to Is Landscape…?: Essays on the Identity of Landscape , released in 2016.

Thinking Through Soil: Wastewater Agriculture in the Mezquital Valley (Harvard Design Press, 2025), by former Dan Urban Kiley fellows Monserrat Bonvehi Rosich (2017–2018) and Seth Denizen (2019–2021), offers an analysis of the world’s largest wastewater agricultural system, located in the Mexico City–Mezquital hydrological region, to envision an improved future environment in central Mexico. This case study presents soil as an everchanging entity that is critical for the health of the planet and all its inhabitants.

Vembanad Lake and Its Untold Stories: Ecological Fragility, Food Sovereignty, and Sustenance Habitability (Notion Press, 2025), by Hasna Sal (MDes ’25), interrogates the historical evolution, ecological challenges, and socio-economic transformations of Vembanad Lake—the longest lake in India, and the largest in the state of Kerala—over the past century. Integrating cartographic and diagrammatic analysis with oral histories by fisherman, oceanographers, and more, the book advocates for a transdisciplinary framework that values localized, experiential knowledge as essential for designing inclusive conservation strategies that support environmental stewardship and social justice.

Dong-Ping Wong in Conversation with Emily Hsee, on the Chinese Merchants Building

Pairs is a student-run journal at the GSD, which centers conversations between GSD students and guests, about an archive at Harvard or beyond. In this excerpt from Pairs 05, editor Emily Hsee speaks with architect Dong-Ping Wong about the history of the Chinese Merchants Association Building in Boston, which was designed by Edwin Chin-Park and completed in 1949. The building was funded by local neighborhood associations and represented Chinatown’s economic and social progress since World War II. It was partially demolished in 1954 during construction of the Fitzgerald Expressway. Hsee and Wong address the history of the building, the culture of Chinatown in Boston and New York, and recent shifts in the perception of Chinese American culture in the United States.

Dong-Ping Wong is the founding director of Food New York , a design firm specializing in transforming environments, from structures to landscapes. Current and past projects have included a Cayman Islands garden and +POOL, the world’s first floating water-filtering pool . Previously, he co-founded Family New York, designing for Off-White, Kanye West, and contemporary art museums.

Emily Hsee is a 2024 graduate of the GSD Master of Architecture I program. She is originally from Chicago and has worked between New York City and Shanghai. Her research and interests focus on multi-family affordable housing design solutions.

Emily Hsee

Historically, Chinatowns across the United States were viewed as filthy slums filled with illicit activity. After World War II, however, there was a kind of rebranding effort. The US adopted the image of the new democratic leader, and China had been an important ally during World War II. As a result, there were efforts to financially invest in Chinatowns and to extend legal rights to Chinese immigrants. This was most clear in the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. There were also social investments as the media began portraying Chinatowns more positively, highlighting them as great tourist destinations. That’s the backdrop for the construction of the Chinese Merchants Association in Boston in 1949, which housed the headquarters of the association and a community recreation center….

It’s the first building in Chinatown that was “self-funded,” which means it was funded through neighborhood associations….Tragically, five years after its construction, a third of the building was torn down to make way for the Fitzgerald Expressway, leaving behind this not-quite-whole building that’s rife with memory, symbolism, and more.

…I’m curious about your reaction to the building. In some ways it’s very Chinatown: a patchwork of aesthetics, an obvious grafting of oriental ornament onto an otherwise Western building.

Dong-Ping Wong

Right now I’m on Google Maps, staring at the facade that got chopped off and replaced and laughing. It’s a weird way to finish off a truncated building. The new facade is very blank, with just one modernist strip window. It’s more modernist than any other building facade in the immediate vicinity. Its blankness is especially surprising because it makes the facade feel like the back of the building, but it faces a lot of traffic and a significant intersection. It feels like it’s waiting for something else to be built next to it.

On the front facade, I didn’t notice that they closed off those balconies until you mentioned it. I originally thought that there was nothing about the architecture itself, except for the pagoda, that felt immediately Chinese or Asian to me. In fact, it actually felt quite German. But when I zoom in on the enclosed balconies, I can see that there are columns inside and also that at some point the balconies were open to the street, to the outside. You see that balcony condition often in Manhattan Chinatown, and it feels much more contextual and part of the neighborhood.

I’m guessing that openness reflected the Chinese Merchants Association’s goals to be a part of the community, so closing it off feels not just like an aesthetic abandonment but also like an abandonment of community connectivity. Otherwise, the decorative elements, like the “Welcome to Chinatown” sign in that chop suey font and the planted pagoda on top, are what stand out to me. It’s funny because it feels like all of the remaining decoration exists from the roofline up, and my read is that the point of the ornamentation is to announce itself to people further away. After the renovation, the building itself became backgrounded.

It must have been so brutal to finish a building and then five years later have it cut off like that.

EH

It’s so brutal.

DPW

I’m sure it was a huge deal in Chinatown at the time. There was probably a lot of pride in the building’s construction. Then five years later, the association lost half of it.

I appreciate how you used the word rebrand to open this conversation. I’ve never thought of the shift in the US view of Asian Americanness after World War II in those terms before. I’m aware of it, but I think rebrand is a perfect way to describe it. The word is so concise, yet it also captures the treatment of Asian Americanness as a kind of product or service. This building is a good example of that. The Asian American community had a little bit of agency to create something for itself, until it was in the way of something that the city wanted. Once the product of Asian Americanness was no longer useful, the city took a bunch of it away.

EH

Chinatowns everywhere have always been vulnerable, and to some extent, their existence always feels conditional. You mentioned agency, though, which is important to talk about. Despite Chinatowns’ precarity, Chinatown does have some agency, and I wonder where you think that is and how it can be leveraged.

DPW

If I had a good answer to this, I would solve the problems in Chinatown. I will say that one of the nice things I’ve learned about Manhattan Chinatown over the last years is how community members of all ages are drawn to activism. Of course, it’s not always effective. For example, there’s a big new jail coming into Chinatown that the neighborhood has been protesting nonstop for years, and still, there’s a point where it feels like a losing battle.[1]

But there are other city projects that the community has been more effective in blocking.

This was surprising to me, given my incorrect assumption that Asian Americans are not that vocal. I’ve come to realize that there’s a lot of internal vocalness, but it’s very rarely broadcast outside of the community. Within the neighborhood, it’s amazing to see so many organizations, associations, and nonprofits being loud. Chinatowns across the US have always been relatively low-income neighborhoods, so I don’t think there’s much of a financial lever to pull. But there is a political lever that I think stops bad things from happening. I wonder whether the community can use that same political leverage to push for changes that benefit Chinatown….

EH

…I want to talk about the role of memory and symbolism within Chinatown. As with the Chinese Merchants Association building, the built environment contains markers of both joy and pain. How central are those symbols to a community or a neighborhood?

DPW

We’re working with two young Asian American clients on a diner project and one of the first conversations we had was about the question “What does Asian American architecture look like?” We were going to different Asian American restaurants as reference points, and we found two examples. One type of architecture resembles the Chinese Merchants Association building: East Asian design elements are clearly translated and grafted onto Western structures. Many classic Chinese restaurants fall into this category: they have very cute, tongue-in-cheek, Asian-like neon signs or calendars and waving cats, but without the ornament, the space and architecture could be anything. There’s really nothing inherently Asian or Asian American.

The other is an architecture that leans heavily toward the exaggerated orientalized architecture that almost becomes a caricature. Both are using this Asian aesthetic for survival’s sake, appealing to what the city wants, but I wonder if the second kind might be more difficult to tear apart or demolish because it has more romanticized Chinese elements. Whether superficially or not, cultural identity is infused into it. I’m thinking about our restaurant design and whether it’s possible to weave Asian Americanness into the bones of the architecture itself, through material, structure, or aesthetics, without the “oriental” look that’s only catering to tourists.

When I was growing up, I hated Panda Express. Actually, I really liked it, but I was never proud of Panda Express. I was ashamed when I went to the mall, because I thought, This is not real Chinese food. Only recently, maybe in the last 10 years, I realized it isn’t supposed to be real Chinese food. It’s Chinese American food.

I’ve been seeing a generation of younger Asian American chefs in the past few years making Chinese American food their own. I imagine something similar happening architecturally: we take an aesthetic that was done for survival’s sake, for tourists, and own it. Can we make it a genuine Chinatown culture aesthetic, which in this case would be referencing not purely American or Chinese aesthetics but a sweet spot that’s somewhere between kitsch, authenticity, and progressivism? I’m particularly interested in kitsch because it’s been very helpful to the survival of Chinatowns. I don’t think an Asian American style necessarily needs to have that tired oriental look, but I think the kitsch aesthetic is a useful tool. It’s like, “Look, we know this is appealing to you, so we’re going to use it. You won’t want to fuck with this building, but we’re going to make it our own.”

EH

It’s almost like an inside joke. While the architecture doesn’t actually reference cliched images of China, we play to our advantage on the assumption that it does. I was at dinner with a friend who’s Chinese, from China, and he told me that he loves going to Chinatowns when he’s in other countries. It’s not because he misses China or because Chinatowns feel anything like China but because they’re their own worlds. That sentiment is useful when we talk about what it means to preserve Chinatown and what exactly makes Chinatown Chinatown.

DPW

Maybe there’s a way to frame these shifts in three phases. I can imagine that when Chinatowns first emerged Chinese Associations were established to protect the neighborhoods. At that point, there were huge vulnerable workforces from China that were being villainized. It makes sense that Chinese Associations had reputations for being involved in illicit business dealings, because Chinese immigrants had few legal rights or protections. After the “rebrand,” after World War II, it feels like Chinatowns became marketing opportunities and started catering to tourists. This shift involved creating a version of Chinatown that was palatable and acceptable to outsiders. I think Chinatowns now are still in this second phase.

One of the reasons we’re having this conversation is because that phase is ending and there’s a new phase that has to—and hopefully already is—happening. To the question about aesthetics, I think my generation felt embarrassed about the kitschy overexaggerated oriental aesthetic, but it is true to how we grew up. Orange chicken, as much as it might not be authentic Chinese food or relate to where our parents came from, belongs to the world we grew up in. It’s just now becoming a source of pride, still with a slight tongue-in-cheek quality, but it’s becoming a source of pride. I want to believe that this shift in psychology means that we’re beginning to own the aesthetic that was originally made for others, and even use that to set some new aesthetics.

This new phase parallels the emergence of Asian American creatives within Chinatown who are integrating that cultural identity we grew up with into fashion, architecture, design, and food. I don’t know what you’d label that third phase, but I hope it’s happening.

Peter Chermayeff on Taking Risks and Embracing Collaboration

For his first architectural commission, Peter Chermayeff landed a big fish: Boston’s New England Aquarium. It was 1962; Chermayeff was 26 years old, had earned his master of architecture degree from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) a mere six months prior, and didn’t yet have a license to practice architecture. He and his partners had just created Cambridge Seven Associates, a multidisciplinary collaborative firm of architects and graphic designers that would soon gain international prominence for a range of work, from small exhibitions to large mixed-use complexes.

More than six decades later, speaking about his early success, Chermayeff humbly observes: “I have a certain willingness to take risks, I suppose. And I have surrounded myself with first-rate collaborators.” Of course, his continued achievement stems from more than a penchant for risk-taking and multidisciplinary collaboration. A world-renowned authority on aquariums, responsible for high-profile projects such as the National Aquarium (1981) in Baltimore and the Oceanarium (1998) in Lisbon. Yet, the self-described “ambivalent architect” nearly didn’t become an architect at all. He had settled on filmmaking when a well-timed risk and a collaborative enterprise changed his mind.

The son of Russian-born modern architect Serge Chermayeff , Peter immigrated with his family to the United States from England in 1940 at the age of four. He and his brother Ivan (four years Peter’s senior) spent the next year with family friends—Walter and Ise Gropius in Lincoln, Massachusetts—while their parents traversed the country in search of an American outpost. Over the following decade and a half, as the father assumed a series of teaching positions (including stints in California, New York, and Chicago), the sons graduated in succession from Philips Academy at Andover. In 1953, the same year that Serge assumed leadership of GSD’s first-year program, Peter entered Harvard College with his sights trained on architecture. He majored in Architectural Sciences, which allowed him to commence graduate work after only three years of collegiate studies. Thus, in the fall of 1956, Peter entered the GSD.

Chermayeff immensely enjoyed his first and fourth years of his architectural studies, taught respectively by his father (“a hell of a good teacher”) and Dean Josep Lluís Sert (“a master and superb teacher.”) “The school was filled with energy and talent,” Chermayeff recalls. “I was intrigued by the power of the community, the quality of my classmates, and the fun we had in exchanging ideas. I was learning as much from my fellow students as I was from the faculty.”

Yet, even while enjoying his time at the GSD, Chermayeff wasn’t convinced that an architectural career was right for him. He had spent a summer in New York working for his brother Ivan, who had recently launched a graphic design firm with Tom Geismar. (Over the years, Chermayeff & Geismar would craft a plethora of highly recognizable logos including those for NBC, Mobil, PBS, and Chase Bank.) Another summer, Chermayeff worked with the Italian sculptor Costantino Nivola in his studio on Long Island as the artist created a large cast-concrete bas relief for an insurance company building in Hartford. As Chermayeff neared the end of his schooling, these endeavors prompted him to think less about architecture as a career and “more so about the visual arts, filmmaking in particular.”

During his final year at the GSD, Chermayeff had achieved unexpected success with a 15-minute experimental film. Titled Orange and Blue, the unnarrated film depicts two rubber balls, one orange and one blue, as they bounce from a bucolic wooded landscape into a junkyard strewn with the detritus of modern life. Taking a liking to the production, a film distributor paired Chermayeff’s short with Ingmar Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly as the Swedish feature toured the United States. Chermayeff found the unanticipated accolade to be “funny, ridiculous, but also wonderful.” What’s more, says Chermayeff, “I realized that, in the course of doing the film, I’d had more fun than I’d had doing anything with architecture.” So, upon graduation from the GSD, in 1962, a year when US officials were urging families to build fall-out shelters, Chermayeff set out to make another film—this time an informative documentary on the effects of nuclear weapons.

Six months later, as Chermayeff was immersed in raising funds and producing the documentary, his friend Paul Dietrich (MArch ’56) suggested they start a collaborative firm that would combine architecture, urban design, graphic design, and industrial design. Chermayeff declined; “Paul,” he explained, “I’m off in another direction. I’m making films.” Yet, the idea had been planted in Chermayeff’s mind.

The following week, Chermayeff made a bold move. He traveled to the Franklin Park Zoo in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood and, without an appointment, approached zoo director Walter Stone. “He must have thought I was crazy. I told him that I thought his zoo was dreadful,” Chermayeff recalls, “and that it could be rethought, reimagined, replanned, and changed for the better if he would allow us.” Stone was intrigued, agreeing to attend a slide presentation in Chermayeff’s Cambridge studio on how the as-yet-unnamed firm would revitalize his zoo. Impressed by their ideas but without funding to hire them himself, Stone introduced Chermayeff to the person in charge of developing a new aquarium in Boston. After a successful meeting, the fledgling firm was included on the project’s short list of architects, and an interview followed. Ultimately, Chermayeff and colleagues were selected to design the New England Aquarium—a lynchpin in the renewal of downtown Boston’. “And that,” says Chermayeff, “is how we started Cambridge Seven.”

As the name implies, seven partners initially comprised the collaborative venture: in addition to Chermayeff, four architects—Louis Bakanowsky (MArch ’61), Alden Christie (MArch ’61), Paul Dietrich (MArch ’56), Terry Rankine—and graphic designers Ivan Chermayeff and Tom Geismar, who simultaneously maintained their New York practice. They were all relatively young (Dietrich, in his mid-30s, was the elder stateman of the group). Yet the men had secured a major project, “an adventure in itself,” recalls Chermayeff, “because it involved reimagining and reinventing a building type—an urban aquarium, a place of encountering nature.” For Chermayeff, though, the New England Aquarium commission took on additional significance: “it meant that I could in fact find my way in this field because the project called for interwoven exhibition design and graphics and would address the content of things as much as the form of the envelope or the planning of the surroundings. It became, for me, place-making with a purpose, driven by content and context.” Opened in 1969, the Boston aquarium played a key role in transforming the city’s waterfront into a vibrant public locale. It also led to more aquarium commissions around the globe.

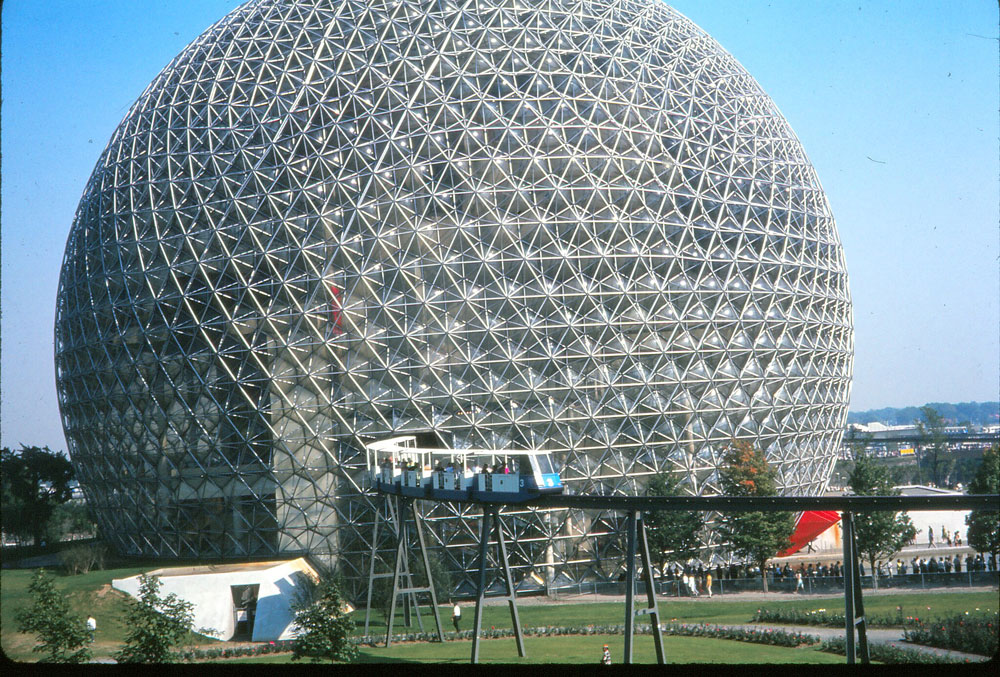

Even before the New England Aquarium’s completion, though, Cambridge Seven acquired two noteworthy projects—”not from the aquarium particularly,” Chermayeff notes, “but from the notion of the firm as a multidisciplinary collaboration.” The first arrived in 1964 when Jack Masey, design director for the United States Information Agency, invited Cambridge Seven to spearhead the US Pavilion for Expo ’67 in Montreal . Chermayeff and the others worked with Buckminster Fuller to make a transparent bubble, a geodesic dome as a three-quarter sphere 250 feet in diameter, which Fuller’s team engineered. Cambridge Seven designed the interior, which consisted of staggered platforms, described by Bakanowsky as “lily pads,” joined by escalators and stairs. Exhibits showcased items from a NASA lunar landing module and oversized works of contemporary art to Raggedy Ann dolls and mouse traps—all products of American creativity and ingenuity. An elevated monorail further animated the pavilion, bisecting the spherical space at the equator as it transported Expo visitors throughout the fairgrounds.

The other prominent multidisciplinary project Cambridge Seven tackled in the mid-1960s involved environmental design for the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) transit system. As Chermayeff notes, “We made some basic changes that had to do with the experience of the user, the people who use the system, riding the trains or the buses, walking through the stations. We developed guidelines and standards and, above all, a system of graphics and identity that unified the different subway stations and gave clarity to where you were and where you were going.” These changes included rebranding the transit system as the “T,” an idea borrowed from Stockholm, Sweden. “We concluded that the ‘T’ would work as a symbol for a lot of very good reasons. Intuitively, if you see the letter T, you can think of transportation, travel, transit, tube. . . so many words that conjure the notion of what it’s all about,” Chermayeff says. Geismar painstakingly created the black-and-white “T” logo, still ever present throughout the Boston region.

Likewise, a version of the “T”’s minimalist spider map remains in use today, coherently depicting individual locations within a larger, unified system. As Chermayeff explains, they color coded the subway lines, providing each line with a geographically derived identity. Thus, the former Harvard–Ashmont Line was renamed the Red Line, referencing Harvard’s signature color. The track running to Boston Harbor and northeast along the sea became the Blue Line, while the Green Line branched toward Olmstead’s Emerald Necklace southwest of Boston. “And Orange . . . well, I just didn’t know what else to do,” Chermayeff confesses. “It was a fourth color, and it made sense to combine with the others!”

Above ground, the colors simplified the user experience, signaling the stations’ affiliations. “As you walk down the street, if you see green and orange, you know that this station takes you to both Green and Orange Line trains. This means that the whole city, the skeleton of the city, becomes more legible,” Chermayeff notes. “Looking back on it,” he concludes with a grin, “in terms of the impact on millions of people over time, I think what we did there was pretty terrific.” That this overarching scheme for the MBTA endures today, nearly sixty years later, suggests that Chermayeff is indeed correct.

Moving into the 1970s, Cambridge Seven continued to garner attention, completing an array of work including museums, educational buildings, and mixed-use complexes, eventually winning the American Institute of Architecture’s prestigious Firm of the Year award in 1993. Chermayeff became known internationally as the foremost aquarium architect, leading significant projects throughout North America, Europe, and Asia. He also continued to make films, including the eleven-part, non-narrated Silent Safari series for Encyclopedia Brittanica that depicts rhinoceroses, lions, and other animals in their natural East African habitats. Chermayeff left Cambridge Seven in 1998 with two younger collaborators, Peter Sollogub and Bobby Poole, and he continues to practice design with Poole.

Throughout his career, Chermayeff, the “ambivalent architect,” has approached the built environment through a multidisciplinary lens, integrating design and visual culture to make useful, inviting, inspiring places for the public at large. Thinking about the profession today, he forecasts an even greater need for collaboration. “An architect is, almost by nature now, an expression of a collective will rather than an individual will,” Chermayeff asserts. “We learn from each other, and we learn by tackling and solving problems that matter. I like to think that in the next several years, we’ll find ways to address issues like housing and the environment more broadly, where instead of individualistic statements, design occurs through more bees building their bits of the hive, reinforcing each other to make urban places that are humane and rich.”

What Musicals Teach Us About Cities

We often think of musicals—whether on stage or screen—as vehicles for catchy tunes and flashy dance numbers. These productions, however, are far more than entertainment. Rather, musicals convey specific knowledge, teaching us about their locales and the people who occupy them. This premise underlies “Understanding Urban Landscape through Art and Musicals,” a Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) J-Term course taught by Trinity Kao (MAUD ’25). Each year prior to the spring semester, GSD students, faculty, and staff are invited to teach non-graded workshops that explore unique, experimental topics. In her J-Term course, Kao positions musicals alongside photographs, paintings, and other works of art as intimately tied to their cultural contexts.

Growing up in Taiwan, Kao was drawn to musicals because they offered insight into American culture, especially the urban environments in which musicals often take place. While maps may delineate district boundaries, street locations, and building adjacencies, musicals offer more nuanced information. The musical West Side Story, for example, conveys the racial tensions that pervaded 1950s Upper West Side Manhattan, alongside the neighborhood’s characteristic fire escapes, roof tops, and highway underpasses. By watching even a portion of the musical, we can quickly acquire a sense of the cultural and physical environment of the particular time and place. And significantly, as Kao notes, “the musical is a form of media understandable by everyone,” no special training required.

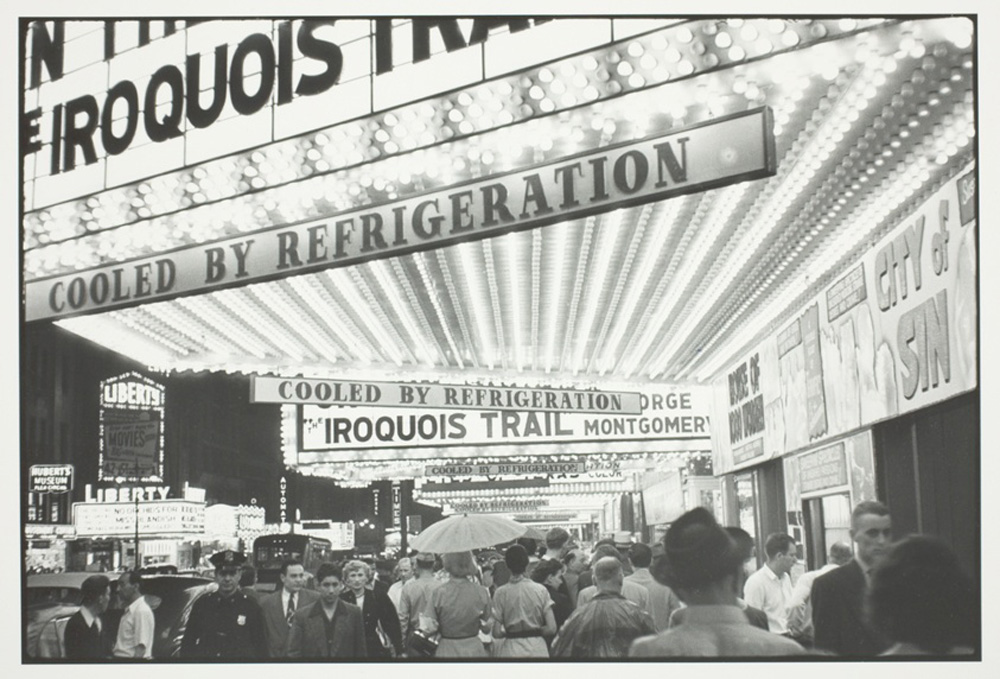

Throughout the course, in total three 90-minute sessions, Kao introduces nearly a dozen musicals, including Legally Blonde, Little Shop of Horrors, In the Heights, and 42nd Street. The preponderance of musicals that Kao discusses take place in New York City or Los Angeles, save for a few outliers such as Hairspray (Baltimore); Oklahoma (Oklahoma City, Nebraska), and Waitress (the American South). Speaking of American musicals, Kao points out that, while none are situated in Santa Fe, both Newsies and Rent contain songs about the New Mexico city, fashioning it as a utopian respite from urban chaos.

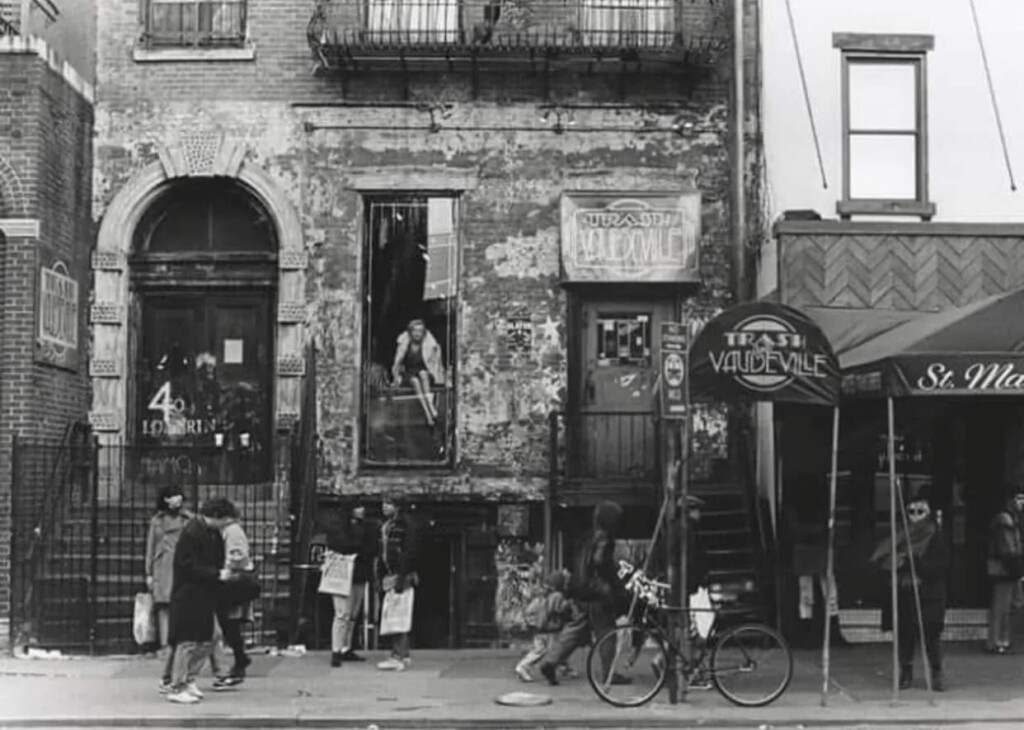

Indeed, the notion of utopia markedly contrasts with the difficult lives described in productions such as Rent. Opening on Broadway in 1996, Rent echoes Puccini’s opera La Bohème (1896), which focuses on a group of poor artists in the Parisian Latin Quarter circa 1830. A late twentieth-century interpretation of its predecessor, Rent relocates the action to Manhattan’s Lower East Side (East Village), a ramshackle neighborhood-turned-haven for Bohemians facing the myriad pressures of poverty, gentrification, and the AIDS epidemic in the late 1980s. No map could convey the predicament faced by the musical’s characters, squatters in a derelict apartment, who amid winter’s bitter chill rely on indoor bonfires for warmth and candles for light. Nor could a map communicate the avarice behind the developer-driven scheme to redevelop this property, despite displacing the struggling artists and the unhoused people who live on the lot next door.

In such a manner, musicals have the power to illuminate the lived experience of a city at a specific moment in time. Simultaneously, their adaptations underscore continuities throughout time. Elaborating on Rent and La Boheme, Kao notes that, despite the hundred years that separate the two stories, “we see the same kind of people living in the two cities. These people have the same kinds of dreams, the same types of struggles, even as the urban structure keeps changing.” Musicals, then, not only teach us about cities; they elucidate enduring aspects of the human condition.

Photo Credits

West Side Story: ©Disney.

Faurer, Indian Summer: Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, transfer from the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. Copyright © Estate of Louis Faurer. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

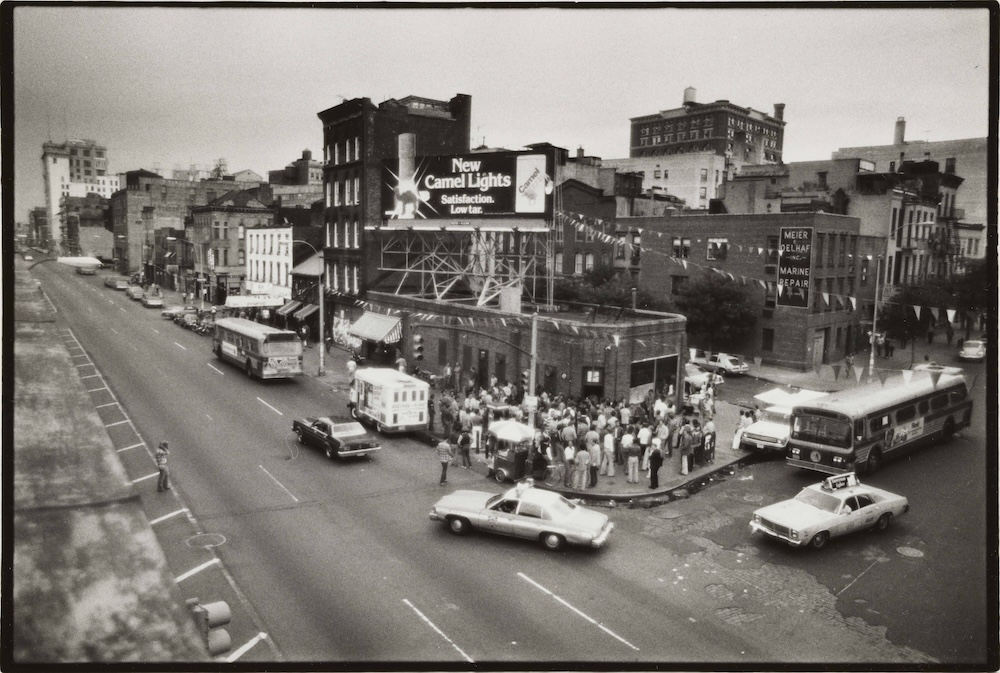

East Village: Photographer unknown. https://medium.com/@michaelcline2323/saint-marks-place-east-village-nyc-a08600b29b66.

Unifying Research and Practice: Sam Naylor

As a Harvard Graduate School of Design Druker Fellow, Sam Naylor (MAUD ’21) traveled the globe to investigate cooperative housing, exploring more than 100 projects over three years. Simultaneously, Naylor worked as an architect full time, co-authored three major housing-related reports, and sustainably renovated a cooperatively owned triple-decker in the Jamaica Plains neighborhood of Boston. Uniting these endeavors and driving this improbably large aggregation of work is Naylor’s abiding interest in housing—what it is, and what it can be—alongside his conviction that research and practice enrich one another.

Naylor’s architectural studies began in 2011 at Tulane University’s School of Architecture, in New Orleans. This was less than a decade after Hurricane Katrina, and the school immersed students in the city’s reconstruction. “Because it was so hands-on, and we were building real things that would happen in different neighborhoods, the design-build program was a big part of what inspired my architectural thinking,” Naylor says. In addition to individual architectural interventions, “there was also a focus on the city itself, working with community members and rebuilding at multiple scales, in a really considered way that was engaged and ecologically specific.”

Following Tulane, from which he graduated with bachelor and master of architecture degrees, Naylor’s experience of thinking about design at multiple scales accompanied him to Los Angeles where he worked for a few firms “on a wide range of architectural projects, from the city scale down to furniture. Slowly,” Naylor recalls, “I became more political and wanted to understand the dynamics behind our cities and what makes it possible for things to happen. What hidden forces set up the game for us as architects? I was curious to see how I in my career, and architects and designers in general, could have more agency in establishing the rules of the game that we then play.” This thinking led Naylor to the GSD, where he began his post-professional MAUD studies in 2019.

Looking back, Naylor describes his two years as a GSD student as “a critical part of my career, a great time to slow down, read and research more heavily, and take classes in different disciplines.” By the second semester, Naylor found himself drawn to housing. “As a design area,” he explains, “housing embodies a lot of the elements in which I’m interested. Housing transitions scale; you have to think about the city, and also about the room and furniture scales, even door handles. It’s also extremely political; you have to be engaged in the world, thinking about the processes through which design and construction will actually occur.” Finally, “housing is intimately connected to our own lives,” Naylor says. “And with the current housing crisis, it is satisfying to work on an issue that matters. Designing housing for communities where I live or work or that I care about is extremely fulfilling.”

Fortunately, the GSD proved an excellent place for Naylor to explore housing as a student and beyond. Graduating from the MAUD program in 2021, Naylor was awarded the Druker Traveling Fellowship, which sponsored his three-year study of cooperative housing design , exploring models in nearly a dozen countries from Argentina to the Netherlands to Australia. Toward the end of the 2021, Naylor was also appointed a research fellow at Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) where, with associate professor in practice of urban planning Daniel D’Oca and professor in practice of landscape architecture Chris Reed, he co-edited The State of Housing Design 2023 , the first book in a new series that addresses issues related to residential design.

Meanwhile, Naylor joined Utile, a Boston-based firm founded by Mimi Love and Tim Love (MArch ’89, also a lecturer in real estate at the GSD). At Utile, Naylor is currently an associate with a focus on multifamily housing, as well as a member of the internal housing research team, which investigates housing and policy-related best practices. In October 2024, Naylor with Utile, JCHS, and the research center Boston Indicators released “Legalizing Mid-Rise Single-Stair Housing in Massachusetts,” a report examining the space-saving benefits of eliminating multiple-stair mandates in this building type. The single-stair report is the first step in “the harder work of making that regulatory change possible,” with Naylor now “meeting every week with people in co-development, housing advocacy, municipal policy, or the state legislature to talk about how we can make that happen.” In addition, Naylor is concurrently working with Tim Love, Amy Dain, and Camille Wimpe on Equitable Zoning by Design , a research project at Northeastern University that explores rezoning for multifamily development following MBTA guidelines, with findings to be released this month.

Concerning the potent mix of research and practice that comprises his career, Naylor feels fortunate to be a part of a firm that supports research and exploration. “It would be advantageous if more places we work supported these tangents because they enrich everything—your work, your connections, your design thinking. Research and practice improve each other,” Naylor affirms. “Research informs theory and then comes back into practice. It’s a form of testing ideas iteratively.”

This philosophy appears to hold sway in Naylor’s personal realm, notably in his very intentional living arrangements. Naylor, his wife Elaine Stokes (MLA ’16, DDes ’25), and a few friends cooperatively own a triple-decker house in Jamaica Plain. They purchased the property and have since embarked on a collective journey to decarbonize, renovate, and reside together, in their individual units, sharing building maintenance, some meals, and dog care responsibilities. Not coincidentally, during the years that Naylor traveled the globe to investigate cooperative housing projects, back at home he initiated his own—a true unification of research and practice.

Winter Reading 2025: Design Books by GSD Faculty and Alumni

In need of new reading for the new year? These recent books by Harvard Graduate School of Design faculty and alumni—published within the past six months and organized alphabetically by title—feature topics from Victorian architecture to geospatial mapping.

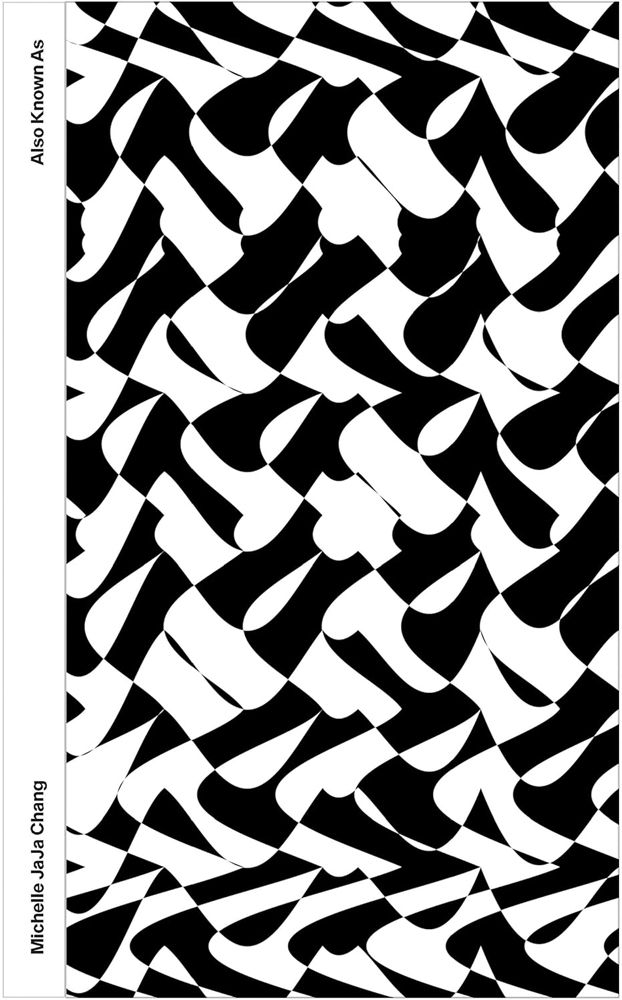

In Also Known As: Uncovering Representational Frameworks in Architecture, Art, and Digital Media (MIT Press, 2024), assistant professor of architecture Michelle Jaja Chang (MArch ’09) ponders relationships between objects and architecture. Drawing on design, media, computation, and art, this book employs texts and images to explore the social, material, and political impacts of architectural systems and design technology.

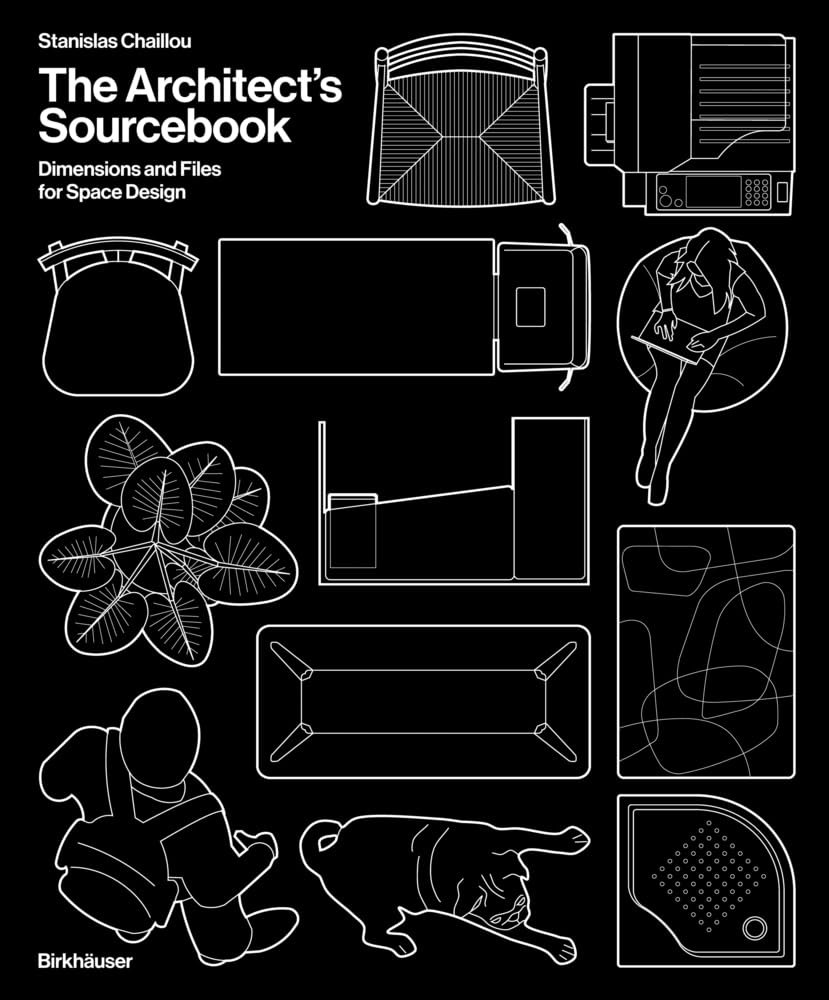

A contemporary architectural manual, The Architect’s Sourcebook: Dimensions and Files for Space Design (Birkhäuser, 2024), written by Stanley Chaillou (MArch ’19), presents a digital repository of typologies, from housing to work to leisure spaces, complete with explanatory texts, general dimensions and guidelines for 2D layouts, and downloadable CAD blocks.

Architecture.Research.Office. (DelMonico Books, 2024), edited by Stephen Cassell (MArch ’92), Kim Yao, and Adam Yarinsky, documents over thirty projects by the editors’ New York–based firm Architecture Research Office (ARO), recipient of the American Institute of Architects Firm Award in 2020. Founded in 1993, ARO is known for engaging, research-driven projects with a clean aesthetic, including the phased renewal of the Rothko Chapel and Campus (ongoing) in Houston; the Brooklyn Bridge Park Boathouse (2018); and the Congregation Beit Simchat Torah (2016) in New York City.

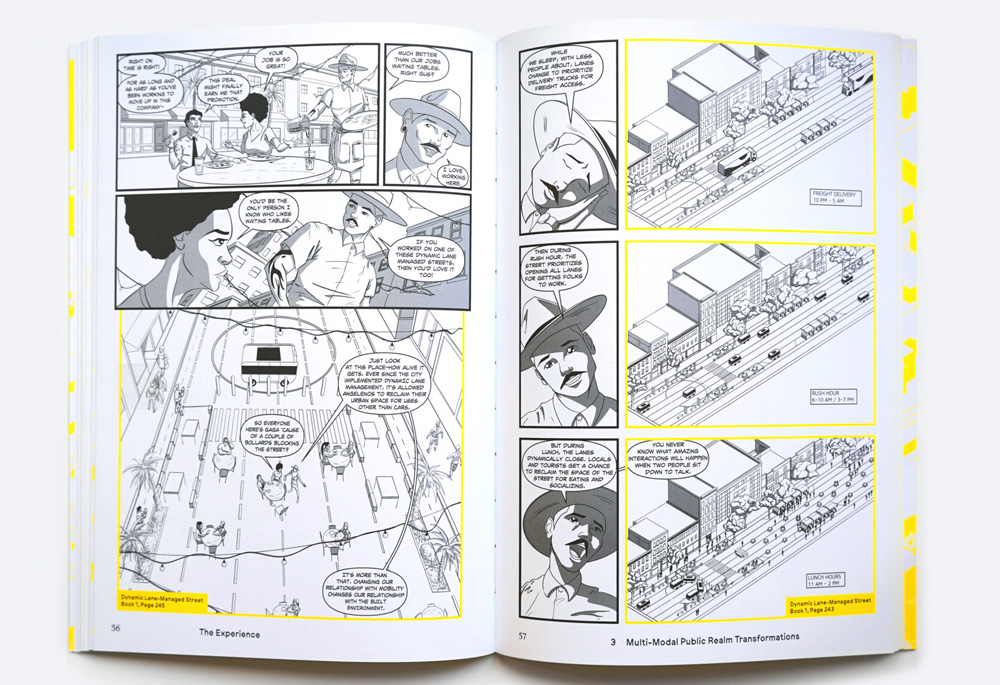

Autonomous Urbanism: Towards a New Transitopia (Applied Research + Design Publishing, 2024), by Evan Shieh (MAUD ’19), explores the latent and transformative impact autonomous vehicles will have on the urban and spatial future of cities. Employing representational techniques of graphic novels, the book explores our recent history of urban transportation and speculates on the typologies and policies that await us with a driverless mobility paradigm shift.

In “Modernism in Three Acts,” published in editor Léa Namer’s Chacarita Moderna: La Nécropole Brutaliste de Buenos Aires (Building Books, 2024), associate professor of architecture Ana María León (MDes ’01) draws on archival documents held at the Special Collections of Frances Loeb Library to explore the architectural context in which Argentine architect Ítala Fulvia Villa designed the monumental Sexto Panteón (Sixth Pantheon) at the Chacarita Cemetery in Buenos Aires.

Juxtaposing an essay by Mohsen Mostafavi, Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design and Harvard University Distinguished Professor, with one written decades prior by the German art historian Max Raphael (1889–1952), The Color Black: Antinomies of a Color in Architecture and Art (Mack Books, 2024) expounds on the relationship between architecture, art, and the color black. Commentary by Swiss architect Peter Märkli and American artist Theaster Gates, along with a broad range of illustrations, offer additional thoughts on contemporary architectural and artistic developments.

Henry Hobson Richardson: Drawings from the Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University (Monacelli, 2024), by Jay Wickersham (MArch ’84), Chris Milford, and Hope Mayo, presents previously unpublished sketches, renderings, and plans of more than 50 projects by the famed nineteenth-century architect, covering building types from houses and railroad stations to churches, libraries, and civic structures. Essays by the authors as well as architectural historian James O’Gorman shed light on Richardson’s extensive oeuvre and enduring legacy.

With IDEAS–A Secret Weapon for Business: Think and Collaborate Like a Designer (Routledge, 2024), Andrew Pressman (MDes ’94) offers a sensible guide for leaders to incorporate elements of design thinking within their organizations. Relying on case studies and practical techniques for fostering creativity and critical thought, this book provides readers with a framework to encourage innovation and teamwork in all business realms.

Large, Lasting, & Inevitable (Park Books, 2025) by Jorge Silvetti, Nelson Robinson Jr. Professor of Architecture, Emeritus, illuminates foundational moments that have shaped architectural thought throughout the past six decades. Edited by Nicolás Delgado Alcega (MArch II ’20), the book features a selection of Silvetti’s seminal texts alongside discussions with figures of the next generation—including design critic in architecture Mark Lee (MArch ’95), Robert P. Hubbard Professor of Architectural History Erika Naginski, Elisa Silva (MArch ’02), Nader Tehrani (MAUD ’91), and Alfredo Thiermann.

Meet Me at the Library: A Place to Foster Social Connection and Promote Democracy (Island Press, 2024), by Shamichael Hallman (LF ’23), positions libraries as spaces that, when properly conceived and programmed, help build inclusivity communities. Drawing on extensive research and examples from throughout the United States, Hallman highlights the significant role libraries could play in healing the rifts that divide our nation.

Monumental Affairs_Living with Contested Spaces (Hatje Cantz, 2024), edited by Germane Barnes (Wheelwright Fellow, ’21), presents interviews, lectures, and other documentation from the Design Akademie Saaleck’s 2023 symposium, held at the former home of National Socialist ideologue and architect Paul Schultze-Naumberg in Saaleck, Germany. The most recent installment in the dieDASdocs series, this text features interdisciplinary explorations into discriminatory architectural and urban practices embedded within the conception, production, and endurance of monuments.

To Nos Lieux Communs (Fayard, 2024), edited by Fabrice Argounès, Michel Bussi, and Martine Drozdz, assistant professor of urban planning Magda Maaoui contributed a discussion on the Haussmannian “chambre de bonne” worker housing typology at the intersection of historic preservation, climate adaptation, thermal comfort, and health. An essay by Antoine Picon, G. Ware Travelstead Professor of the History of Architecture and Technology, addresses the complex global geographies of data centers.

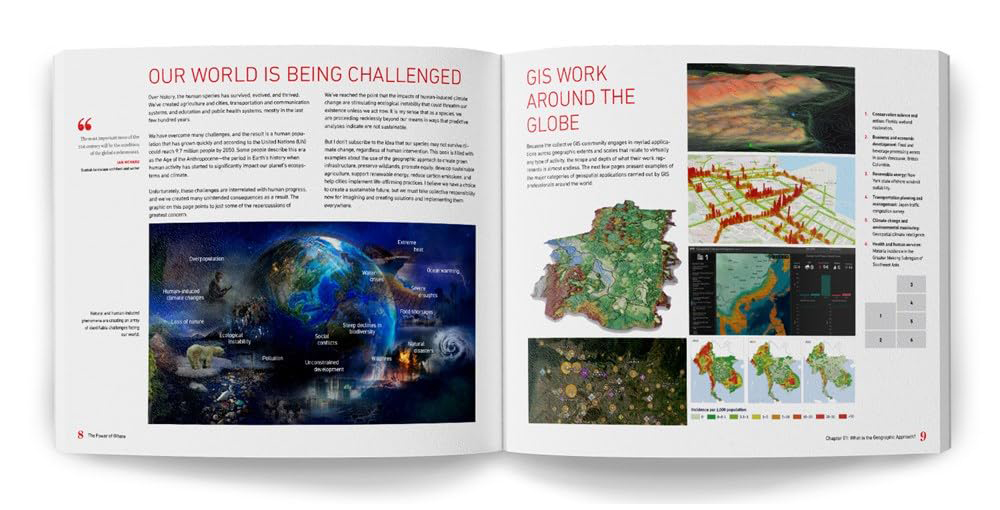

In The Power of Where (Esri Press, 2024), Jack Dangermond (MLA ’69) details the history and advancements of geographic information systems (GIS), presenting mapping as a problem-solving method that allows users to perceive and understanding patterns of all kinds—from spatial to environmental to demographic. Architect and designer Richard Saul Wurman described the richly illustrated book as “a bible of the types of maps, cartography, spatial analysis, and diagrams that can bring our ideas for the future to life.”

Radical Atlas of Ferguson, USA (Belt/Arcadia Publishing, 2024), by Patty Heyda (MArch ’00), probes the planning policies that shaped the St. Louis suburb where, in 2014, racial tensions erupted following the murder of 18-year-old Michael Brown. Using more than 100 maps, Heyda examines philosophical, financial, and design-related forces that set the stage for this violence, prompting readers to consider for whom cities are built and how design impacts everyday life.

Revitalizing Japan: Architecture, Urbanization, and Degrowth (Actar Publishers, 2024) features the work of young architects in Japan who are practicing in ways that respond to the post-growth condition of the country’s shrinking population. Co-edited by Kayato Ota and Mohsen Mostafavi, Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design and Harvard University Distinguished Professor, the book contains texts by architect Toyo Ito and community designer Ryo Yamazaki and photos by Kenta Hasegawa

An Interview with Richard Sennett: Democracy and Urban Form

In fall 1981, the eminent sociologist and urban theorist Richard Sennett delivered six public lectures at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), focused on ways in which the city’s spatial characteristics can foster—or forestall—democracy. This month, more than 40 years after the lectures’ original debut, Harvard Design Press and Sternberg Press published them as Democracy and Urban Form . In the book’s preface, Diane Davis, Charles Dyer Norton Professor of Regional Planning and Urbanism at the GSD, notes that despite the lectures’ age, they maintain relevance, inspiring designers “to think ethically, critically, and responsibly about which kinds of cities and societies they could be producing if they understood how individuals and groups relate to the spaces that they as professionals are designing.”

Harvard GSD’s Krista Sykes talked with Sennett about the evolution of his thoughts on urbanism, the need to take architecture seriously, and the fundamental importance of encountering others unlike oneself. Their interview followed a series of talks and panel discussions held at the GSD in October to celebrate the publication of Democracy and Urban Form.

Krista Sykes: Many concepts from your 1981 lectures hold true today; at the same time, your thoughts appear to have shifted in some ways. For example, during the panel you stated that, in recent decades, you have become more interested in “the mobilizing power of architecture,” which I understand as architecture’s potential to shape human interactions, rather than in its representative or symbolic abilities. What motivated this shift?

Richard Sennett: A couple of things. After I left the United States in the late 1990s, I went to the London School of Economics [LSE] and set up an architecture and urban studies program with Richard Burdett. This program was orientated to practical solutions to problems in Britain. It was a new country for me, and the notion of actually problem-solving—that’s the DNA of the LSE—got me thinking about what architecture could solve in a practical way for problems about economic inequality and so on. Yet, I also was very resistant to that because I think that architecture should be visionary rather than pragmatic. And I began to experience this as a very useful contradiction. My impulse was to say, “let’s think about what might be.” My colleagues at the LSE were thinking, “well, what do we do next? The government has asked us to solve this problem next year.” That stimulated me to think more about mobilizing our architecture.

A second aspect that made me believe in this: I was very struck in Britain that younger architects had lost faith in architecture. They thought it was only a representation of social and economic conditions. That seemed to me very sad—a very sad take on a profession which you think is merely the puppet of the social order. And although I’m trained as a sociologist, I don’t think sociology has that kind of power over the imagination, particularly of people who know how to practice an art.

Yet another thing that really got me going about the mobilizing power of architecture was that I worked for the United Nations for 10 years. In poor countries like Mali or Ghana, it was hard to maintain that the way things are built has nothing to do with the way in which people live. When you’re in a country in which there aren’t enough schools to go around, thinking about what a school should look like is part and parcel of being with a scarcity of resources; it’s not something separable from it. Certainly, the people that I worked with in Sub-Saharan Africa and also in the Far East didn’t see a divide between the expressive qualities of architecture and its practical qualities. That’s a distinction that happens in more privileged societies.

I was reminded of this a few months ago. We have a housing shortage in Britain, and a top housing official declared she didn’t want to build something that was beautiful. She wanted to build something that served a practical need. Only in a very spoiled, rich country could you draw the distinction between quality and quantity. That’s how I came to be much more interested in the qualities of how things look, the qualities of architecture that are of social value.

Likewise, in your 1981 lectures, you emphasize how cities foster democracy by facilitating discourse. Today, your focus is more on bodily presence—what you have referred to as the “democracy of the body.” What prompted this turn?

Well, I think part of the reason that a lot of young architects that I was teaching in London had lost faith in architecture was because they looked at architecture as a discursive practice. It isn’t. Certainly, the political aspects of democracy are as much physical and nonverbal as they are verbal. We always think about democratic form in terms of discourse, and that seems very limited to me. So, I gave a course one year, a research seminar called “What is a Democratic Door?” Originally, people thought this was a joke. But after three months, I had woken them to the notion that, yes, you can embody democracy in the form of a door. It was part of the same shift of taking architecture more seriously.

Perhaps architecture embodies greater power when the focus is on bodily presence instead of discourse, taking a person’s willingness to verbally interact out of the equation. People are exposed to difference simply by occupying a given space with others.

Oftentimes, people will embody a practice that they can’t or wouldn’t explain. It’s true about all aspects of life, that people do things which they are not consciously masterminding. That’s certainly true about the relations between people in social space, in physical space. An assembly line can be racially mixed, yet the people working on it aren’t thinking about what racial integration is. They’re just working together. That’s another aspect of this same shift; it’s too great a burden on people to explain what they’re doing as though the actions that they’re taking are consequences of conscious decisions. There’s a whole issue about democratic theory: often we act on knowledge which is not fully articulated to our self.

How does this translate to environments that lack the density and diversity for such exposure to difference? I’m thinking about the current political divide and our pending presidential election. How might we promote democracy outside of urban situations?

I’m quite worried about this. I mean, there’s no reason why people can do things unconsciously that are bad for them. When you look at Trump’s audiences, they’re all old, or mostly old, and they’re mostly white. I’m not sure those rallies could have actually worked if there were significant numbers of Black people or significant numbers of kids.

I had one of my students examine one of these rallies to take a reading on how old people were and how racially mixed they were. As you can imagine, up in the front near Trump’s rostrum, about five or six rows deep, it’s all mixed. When you get behind that, it’s a sea of whiteness, and it’s a sea of people who are, like me, going bald. My sense of it is that, if these are people who don’t have much daily physical experience being with people unlike themselves, that lack of physical interacting with people unlike oneself can easily lead to fantasies about the other, about who they are. That’s part of what we are facing. There are lots of studies showing that the more racial mixing you have in workplaces, the less racial prejudice is felt on both sides of the divide.

This dovetails with my final question. The 1981 lectures underscore the need to expose people to difference as a democratic undertaking because it allows them to understand themselves as one among many. You describe this experience as one of solitude. “In modern cities,” you stated, “we’regoing to have to come to terms with this new order of solitude.” How might you reposition this experience for the present day?

Well, the ultimate form of solitude that people are experiencing now is online. There’s an editing out of anything that people don’t want to hear. Online you’re in an echo chamber, essentially. That takes us back to the physical city where you have experiences in which you can’t just push a button and withdraw from other people. This has an old history. One of the reasons that politically conservative people don’t like to use public transport is because, involuntarily, there are people on buses or subways who are not like them. It’s a well-known sociological phenomenon. That’s why a lot of Americans like cars, because they’re like an isolation booth. And online has become an evolution of the that. You’re a button away from withdrawing, from being exposed to people unlike yourself.