The GSD introduces new summer opportunities and recharges long-standing ones, aiming to foster a productive summer despite pandemic-induced complications.

Cooperative farm organizations for BIPOC communities. Pandemic-proofed parks, offices, sidewalks, and restrooms. New strategies to ensure accuracy of census and GIS data in African cities.

While varied, these topics are united by design’s potential to intervene in precise ways, as well as by a fresh urgency given the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. They are among the 227 investigations that students and recent graduates will pursue this summer as the GSD introduces new avenues for academic and professional enrichment, and continues to consider the direction and process of design research in an altered global environment.

Amid office closures and precipitous unemployment levels, traditional summer work and learning opportunities have evaporated—especially for students and recent graduates. This dynamic introduces a double-headed challenge: how might students continue to advance their ideas while also gaining professional experience?

“Students have always used summer months to expand on what they’ve learned, by working in offices, partnering with peers on design competitions, traveling to see projects in situ, or advancing research,” says Sarah M. Whiting, Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture. “The pandemic has eliminated many of these valuable opportunities, so we felt that it was critical to support our students, including those graduating into this difficult moment.”

At the heart of the GSD’s effort is the new Student Emergency Fund (SEF), launched on March 10, which provides summer research grants for GSD students and 2020 graduates, and ameliorates some of the logistical and practical complications stemming from travel restrictions. SEF’s research grants offer latitude and elasticity for students: there are no grades or credits to be pursued, no formal supervision required—though each recipient will offer a written summary of their research at its conclusion. In order to assist students in advancing their individual research, the Office of the Dean bolstered the research funds raised via SEF efforts with a matching donation.

Amid office closures and precipitous unemployment levels, traditional summer work and learning opportunities have evaporated—especially for students and recent graduates. This dynamic introduces a double-headed challenge: how might students continue to advance their ideas while also gaining professional experience?

“This was an opportunity, as a GSD family, to wrap our arms around our current students and take a specific action in the unprecedented moment of a global pandemic,” says Peggy Burns, Associate Dean for Development and Alumni Relations. “SEF highlights that the GSD is very much a community: alumni taking action to help support students, with our own faculty among those alumni who have so generously offered various forms of support.” The school’s community of alumni and friends has contributed directly to the SEF while also responding with enthusiasm to requests for increased internship opportunities for GSD students.

The GSD is also reshaping traditional summer offerings in order to pave new pathways toward students’ professional enrichment. Irving Innovation Fellows, selected annually, will collaborate with the GSD’s Innovation Task Force over the summer in order to conceptualize a digital learning environment more nuanced than the one generated this past spring. The school is also providing additional funding to enable teaching assistants to begin their Fall 2020 work during the summer, so they can provide support for courses pivoting to remote teaching and learning in the fall. And it is encouraging faculty to continue hiring students for summer research and design work.

The 227 students and recent graduates who will pursue research this summer are covering a range of topics and perspectives, many of which have been influenced by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. A snapshot of some of these projects and their early-stage germination reveals what GSD students have been pondering over the past few months, how they hope to make use of this unconventional summer, and why they consider their research essential given today’s conditions.

The future of co-working spaces

For years, Francisco Brown (MDes CC ’20) has been studying the real-estate models behind co-working spaces, as well as the broader implications of the so-called sharing economy. As more and more businesses shifted to remote-work arrangements this spring, Brown’s question suddenly transformed: instead of “How do co-working spaces work?,” he was asking, “Will they work at all?” And, if they can’t: What happens to all of that real estate?

“Even though co-working has evolved in a variety of operational and business models, co-working is, in principle, about the community, and its host spaces are about collaboration and proximity,” Brown observes. “The current conditions beg the questions: How can a business model that revolves around renting dense shared-office space stay afloat with social distancing rules and in the advent of what may be the worst economic crisis in a century? How can design research explore new ways to reuse, adapt, and speculate about these spaces in the face of the most significant cultural and economic shift in our times?”

To address these questions, Brown will work alongside research advisor Jacob Reidel, Assistant Professor in Practice of Architecture and a senior director at co-working start-up WeWork. Brown aims to first collect relevant news and data around regulations, analysis, and ideas on design responses to social distancing rules. He then plans to interview academics, co-working-space managers and designers, and organizational scientists to discuss the opportunities and challenges that co-working spaces are facing. Ultimately, he will consider design adaptation and typological hybridization for the millions of unused square footage of space that co-working chains currently hold.

Adapting Hawaii’s comfort stations in the face of COVID-19

Like offices, public restrooms are a cornerstone of urban and civic space, and they, too, have been stress-tested by the COVID pandemic. Kaoru Lovett (MArch ’20) had been researching Hawaii’s so-called comfort stations as a design expression of utilitarianism, one upon which architectural identities have been constructed. The comfort stations, which were conceived during the postwar boom years of the 1950s and 1960s, offered local designers an opportunity to bring regional materials and era-specific aesthetics into what would otherwise be generic, utilitarian public bathrooms.

“The public comfort stations of Hawaii are an interesting precedent, as the scale and timeline of the public project was immense, nearly 200 pavilions over the span of 30 years,” Lovett says. “These pavilions were affiliated with a larger effort to shed light on the budding island destination, establishing some of the foundational work upon which the architectural identity of Hawaii is built.”

While Lovett had initially researched the relationship between the identity and the construction of comfort stations, now he’s wondering whether their inherent utilitarianism can satisfy today’s newly charged public-health concerns. Like Brown, Lovett has watched his original research interests reshape and gain dimension in light of COVID, though not fundamentally transform. This summer, he will examine—from afar—how to adapt Hawaii’s comfort stations to accommodate post-COVID standards of sanitation and social distancing.

“My earlier interest with these public facilities as architectural ‘image’ models has coincided with the attention brought on by recent events,” Lovett says. “This creates an opportunity to approach these pavilions with a particular interest: construction logic and building imagery as strategies for resolving issues of public health.” Given Hawaii’s current plans for phased reopening of public spaces, the attendant need for safely designed public restrooms is growing in urgency.

Lovett anticipates that strategies revealed through his research process—whether they be methods of organization, construction, or technology—will find application in public restroom facilities more broadly. “My aspirations are that the specificity of this precedent will act as a platform to engaging in a larger discourse on public health and sanitation through our post–COVID-19 society,” he says.

Reimagining online space

For Emma Ogiemwanye (MUP ’20), a long-standing research interest in virtual presence has been supercharged in recent months. After a five-year stint at Google, Ogiemwanye arrived at the GSD aiming to explore how urban planning theory and practices might be applied to the Internet in order to help make digital spaces safer, more just, and more equitable. In other words, she wanted to consider how the skill sets of an urban planner, trained in analyzing complex issues of policy and governance and in addressing needs of communities, might be applied to the design of online spaces.

As part of her GSD thesis, Ogiemwanye created a taxonomy of strategies that some Instagram influencers invoke to subvert the normative performances featured on the platform. Her research centers on Black women influencers and explores the myriad ways they navigate and reimagine online space. She has taken particular interest in how these influencers have pulled digital levers to elevate joy, activism, and access to social capital and art through their content.

Ogiemwanye observed that COVID has pushed much of cultural life online. And it has simultaneously revealed health disparities across race, especially as Black Americans are suffering and dying in disproportionately high numbers. In that complex tangle, Ogiemwanye saw the dual narrative so familiar to Black America, queer people of color, and other multiply oppressed communities: creativity and ingenuity emerge in the face of danger and pain.

“Inequalities in access to safety and well-being are now plainly seen and are finally being decried in our physical world. My work stands to point out how dominant online platforms perpetuate these same extractive logics to maximize profit,” Ogiemwanye says. “I hope this transformative moment will result in us reimagining many systems, from housing to healthcare.”

With the support of faculty advisor Lily Song, Ogiemwanye plans to continue descriptively mapping social-media activity by observing how people move and interact online. She believes that she can help encourage what she describes as “more liberatory possibilities” for digital spaces. “This is, in part, a project to build better digital ecosystems as we increasingly spend more time online, while also capturing a snapshot of this unique moment in human history,” Ogiemwanye says. “Online platforms should be included in any list of structures requiring reinvention.”

New forms of food sovereignty

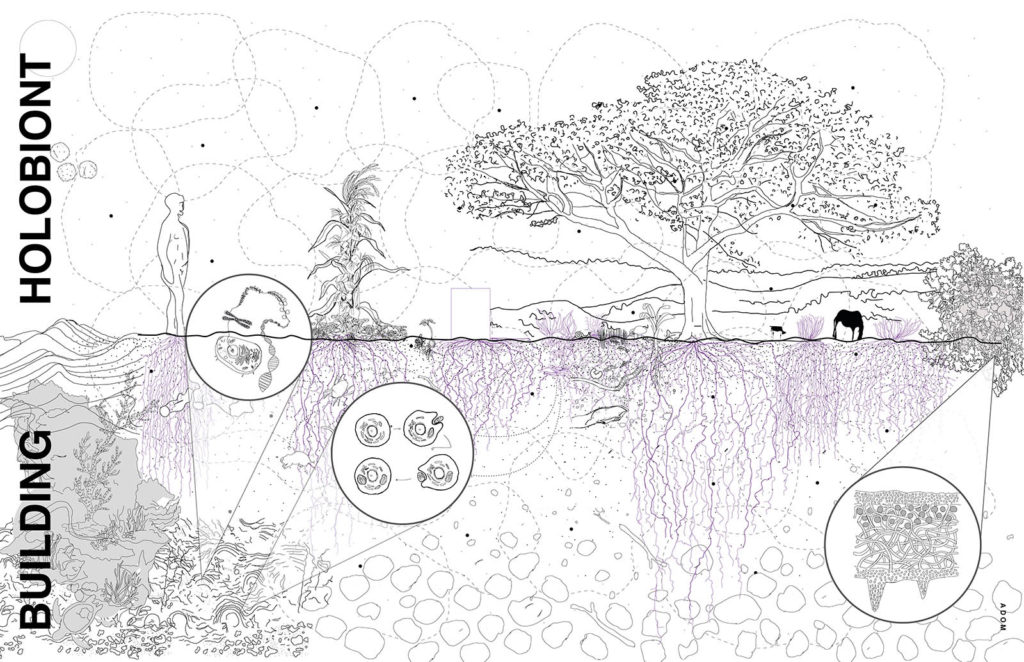

The pandemic has revealed numerous social structures and behaviors that require such reinvention, or at least reconsideration. Throughout the world’s food systems and networks, for example, changes in both work and consumption patterns introduced logistical logjams and supply shortages, highlighting ongoing concerns over labor, supply, equity, and security. Over the course of her GSD studies, Adriana David Ortiz Monasterio (MDes ADPD ’21) has been investigating food sovereignty—explained broadly as the right of a community or a people to define and control the systems and policies that produce the food they eat. She has focused especially on the diversity and conservation of heirloom seeds.

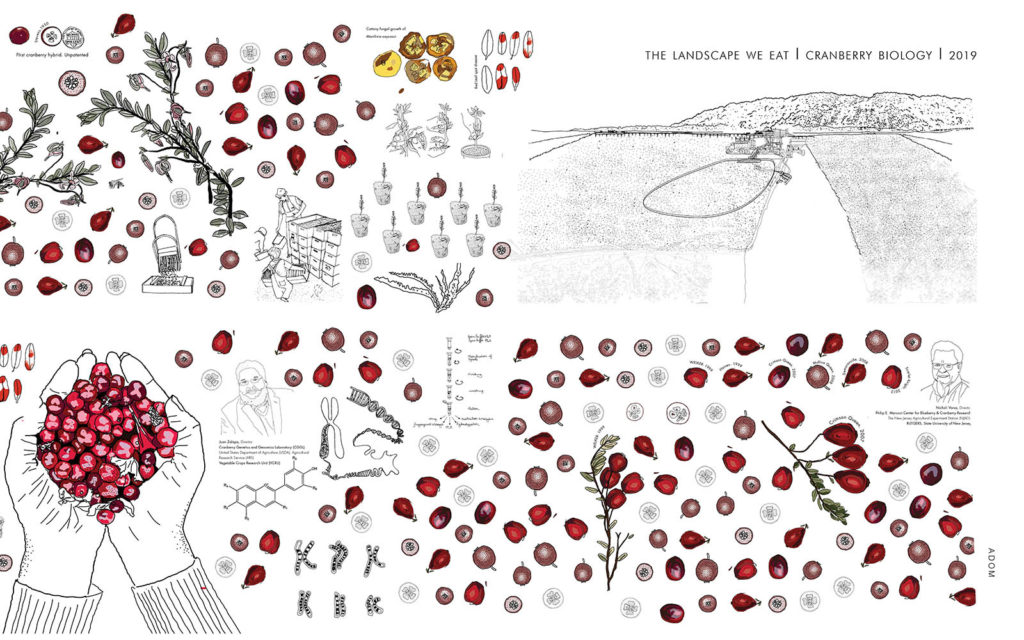

A Fall 2019 GSD course, “The Landscape We Eat” with Montserrat Bonvehi Rosich, had inspired David to assess the full network of food chains and their inherent social and environmental impacts. And Malkit Shoshan’s Spring 2020 studio, “Interdisciplinary Art and Design Practices,” motivated David to apply design in order to engage social issues.

As COVID brought about food instability and other problems throughout global food systems, David saw her ongoing interests come into sharper relief. “This is a crucial moment to delve further into the relationship between food supply chains and food sovereignty for a nation,” she says. “The security of our food sources and availability is critical for the future of our communities. Understanding our food chains means understanding the origins of our food, the seeds used, chemicals, soil, water, field ownership, the architecture of the system, transport, storage, and human labor. I am interested in speculating on new forms of food networks for the city that can result in food sovereignty for communities in danger of famine, and allow for better ways of dwelling with care in the future.”

Based in Mexico City, David will engage that city of 22 million people as a sort of research site while she consolidates previous quantitative research and begins applying it to case studies. She aims to organize her summer research according to the different food-supply spaces of Mexico City—including supermarkets, temporary markets, and organic farmers’ markets—while layering in a COVID-specific frame: food systems before, during, and after a pandemic condition. She hopes to produce a booklet cataloging methods of ensuring food sovereignty for Mexico City, and ideally for other cities and regions around the world. Bonvehi and Shoshan will advise David throughout her study.

Courtyard typology in the Italian countryside

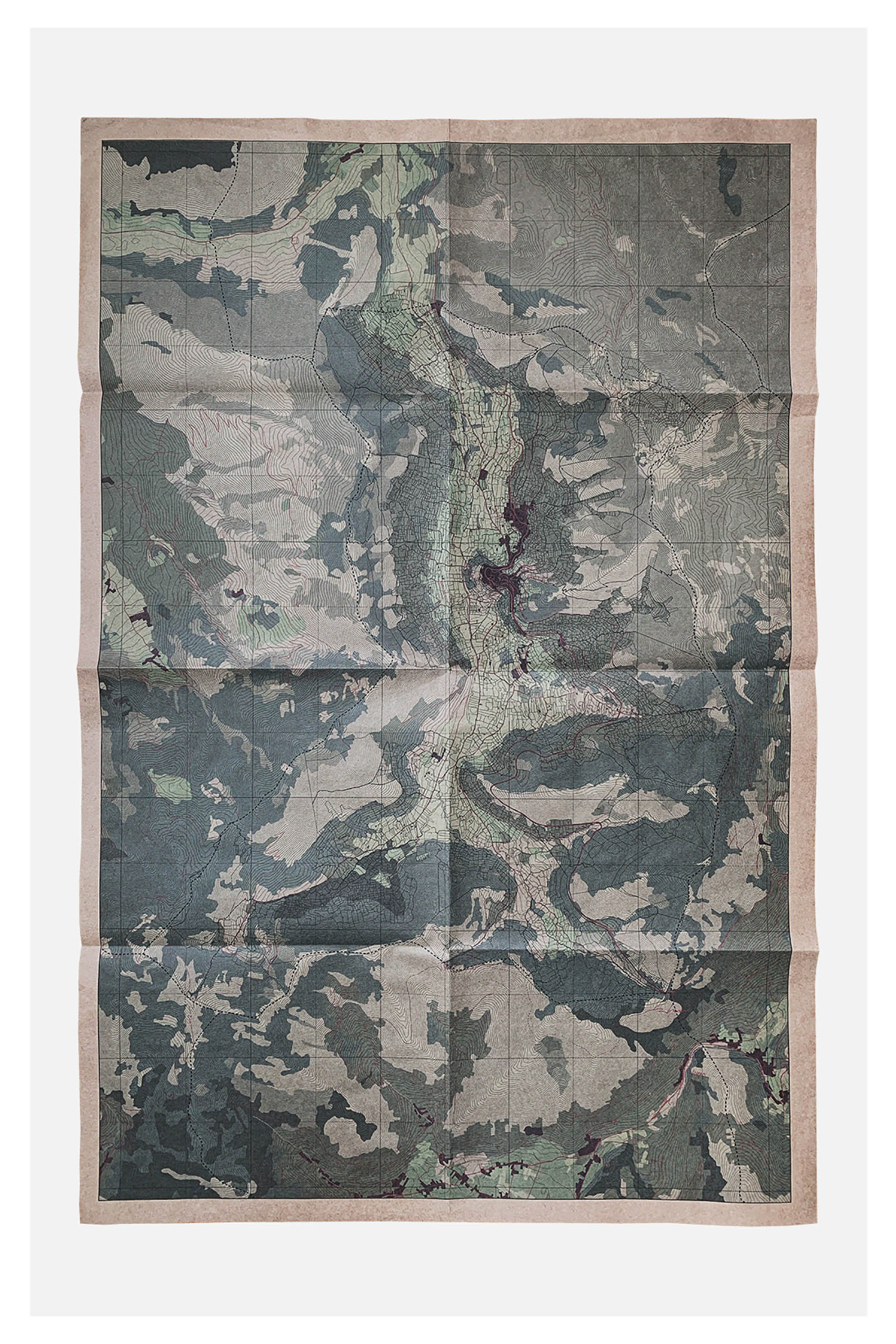

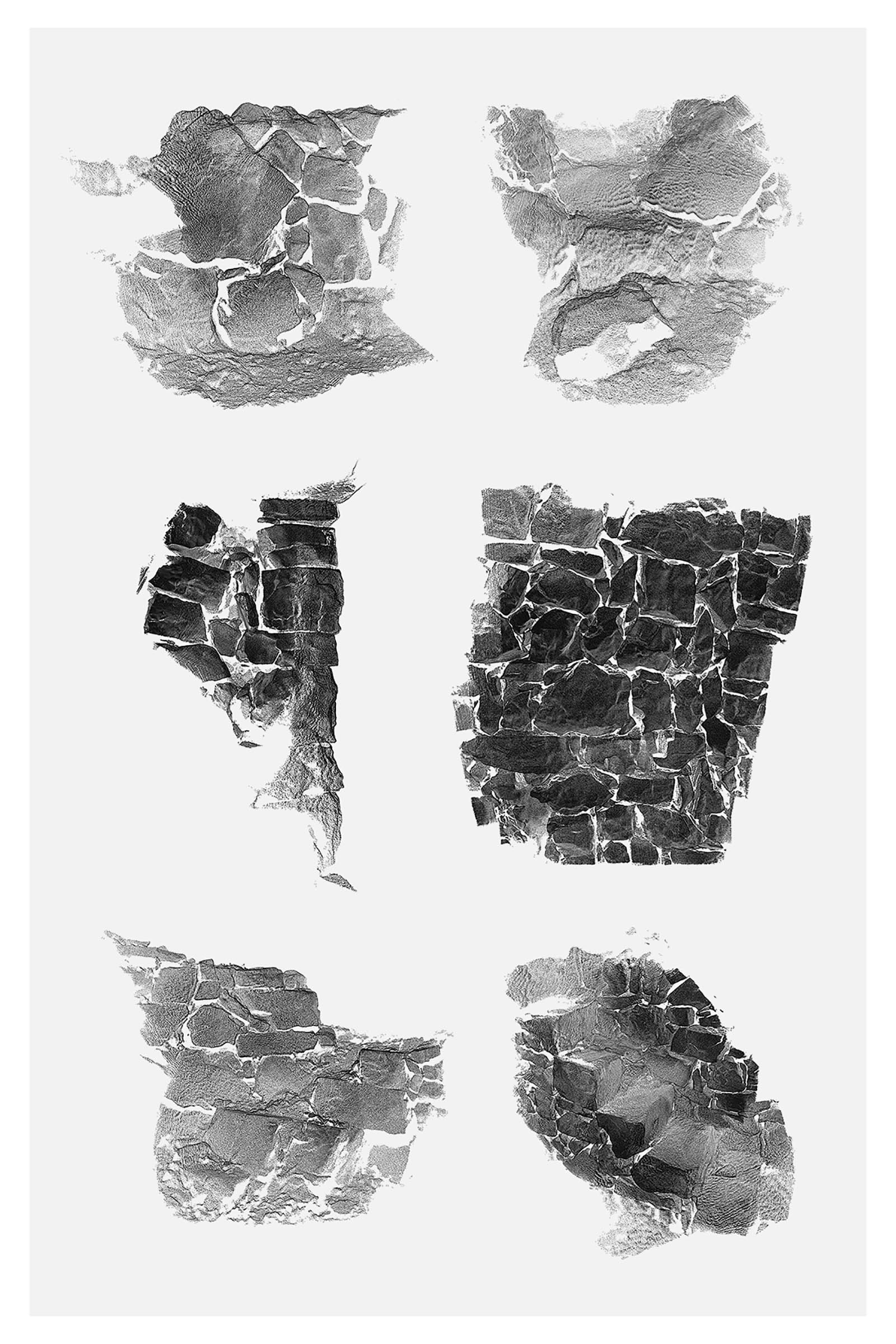

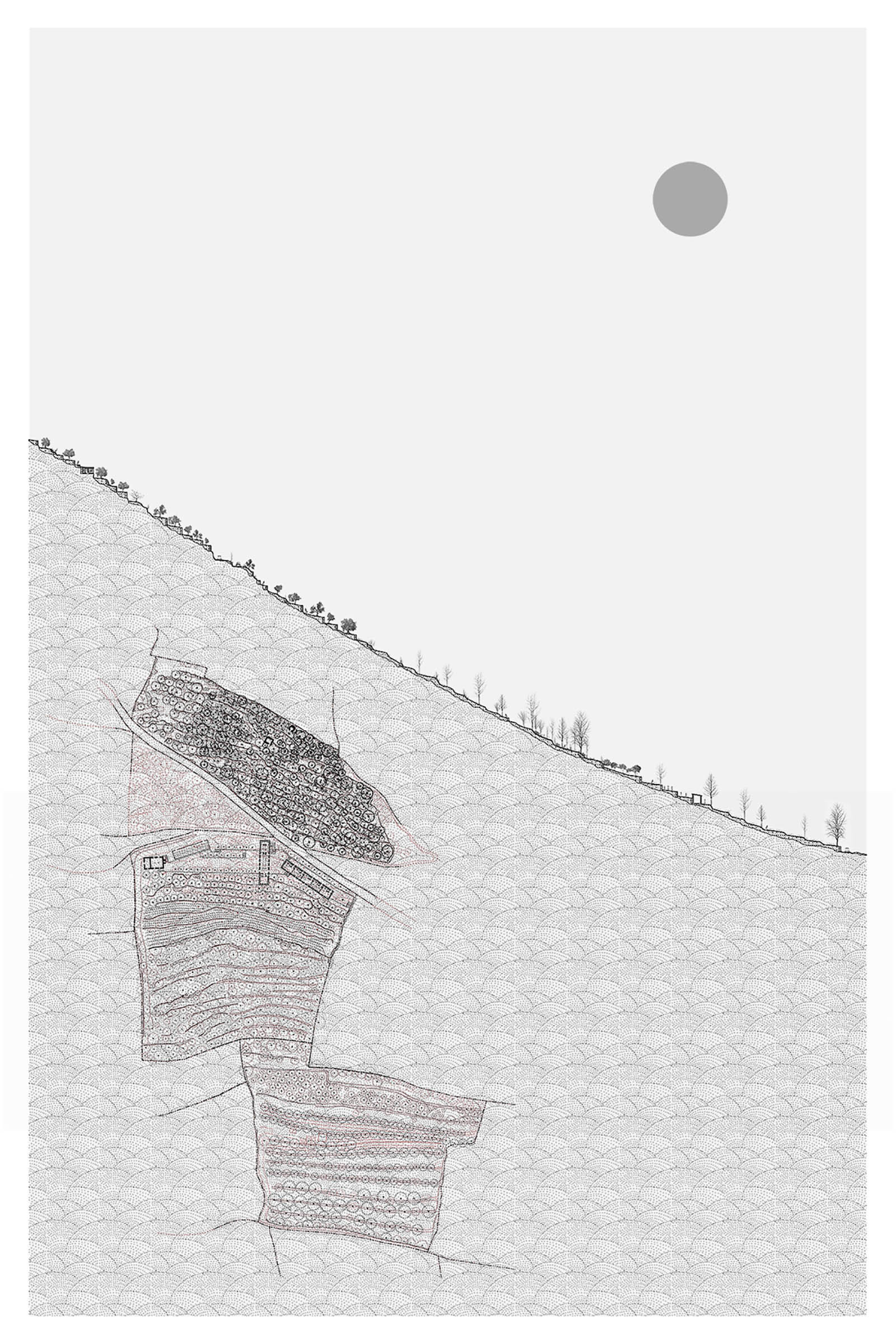

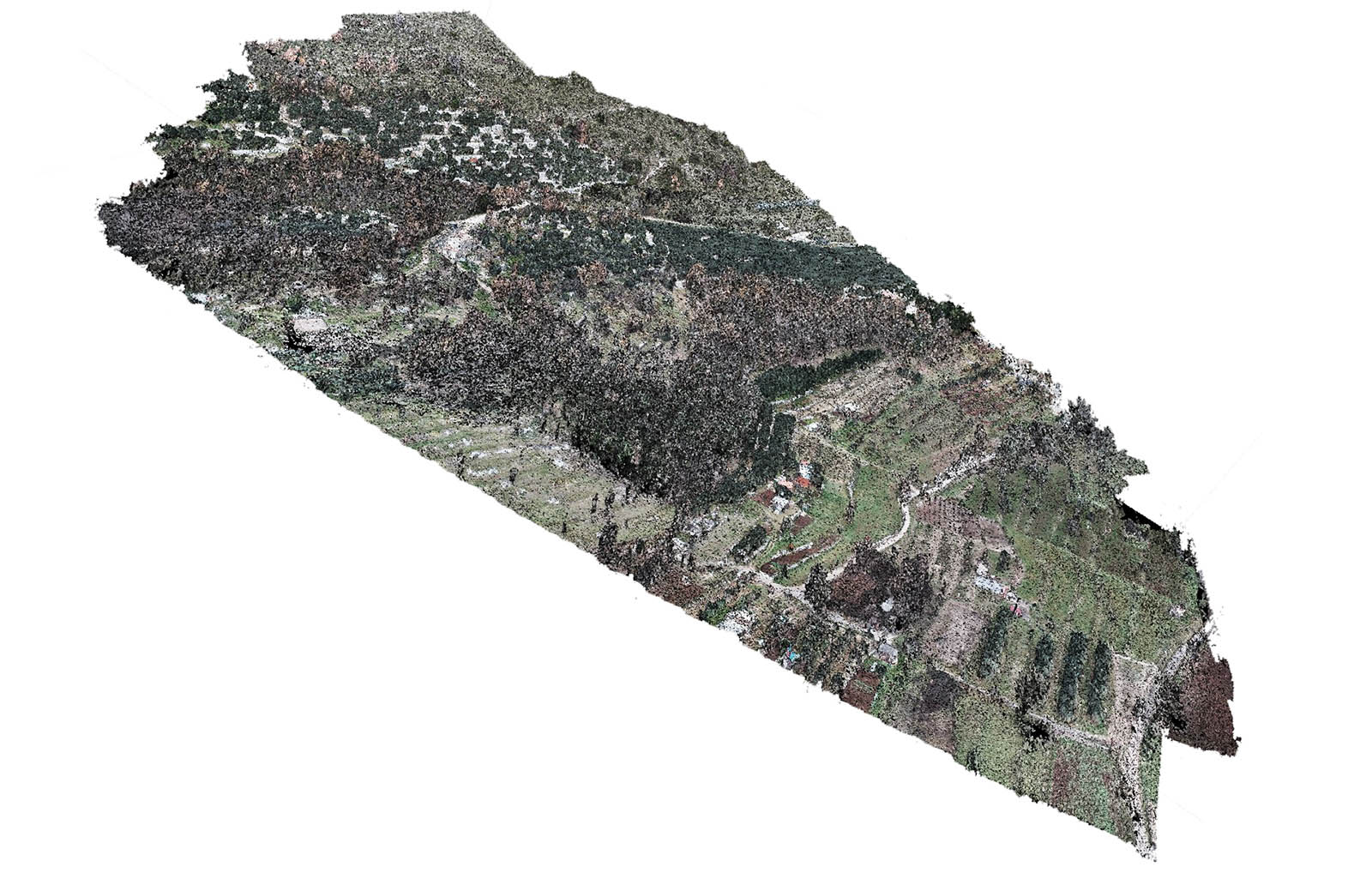

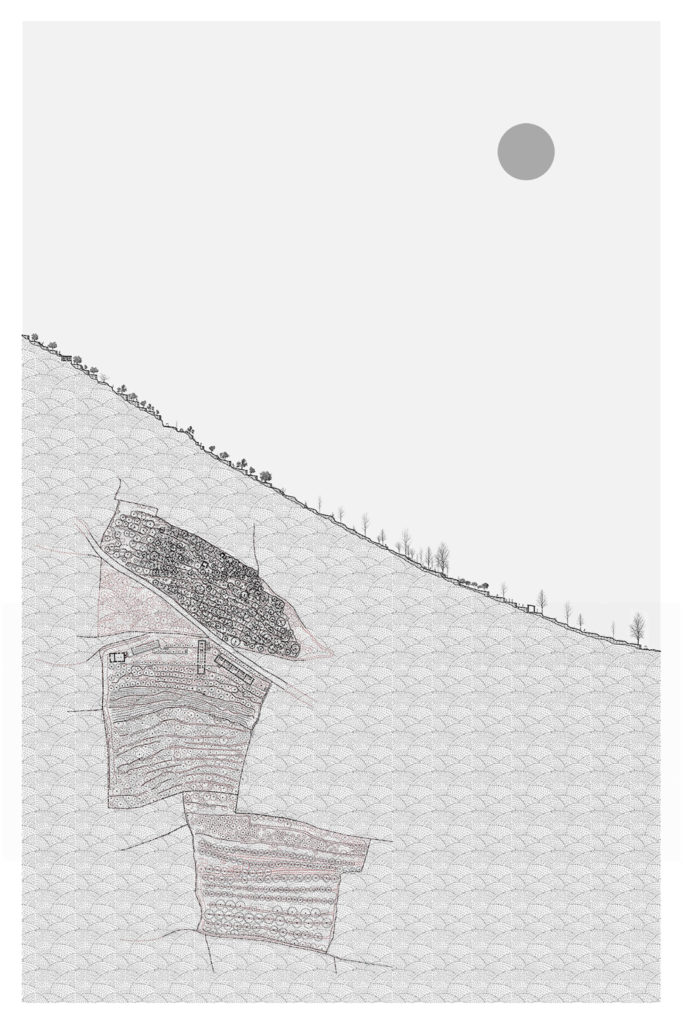

Meanwhile, other students are taking up the holistic urban development process itself as a question worth interrogating. Nicolás Delgado Alcega (MArch ’20) has spent much of his last three semesters at the GSD researching cities and towns that dot the Italian countryside, with their medieval urban cores and attendant issues of agricultural land abandonment, soil erosion, depopulation, and disinvestment. Seeking adaptation strategies for these communities, he has seen a rising interest among younger generations in agriculture, motivated by economic downturns in cities, environmental degradation, and the loss of cultural heritage.

The research that Delgado Alcega develops over the summer will offer a detailed analysis of specific architectural and urban issues that his previous work revealed to be important in the socioeconomic transformations of the site of study. Aiming for concrete solutions, he will test whether the courtyard typology, as an intervention, might resolve or address issues of accessibility, structural stabilization, and sustainability that have emerged over his research thus far.

In particular, Alcega will take up the Italian town of Vallecorsa as a case study, in which he will propose employing the urban medieval block to accommodate emerging ways of life, programs, and pragmatic needs. Alcega benefits from testimonies and other research he gathered during a two-week site visit to Vallecorsa last winter, and he is grateful for the time and space in which to carefully process and strategize the research he has in hand.

Alongside his collaborator, Ginevra D’Agostino, a student at MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning, Delgado Alcega plans to continue a partnership with Vallecorsa’s Cooperativa Agricola La Carboncella, a local organization dedicated to rethinking the future of the area’s historic landscapes. With D’Agostino, he also hopes to incubate a related start-up venture through the Harvard Innovation Lab. Jorge Silvetti, the Nelson Robinson Jr. Professor of Architecture, will remain involved in Delgado Alcega’s work over the summer, having advised the project over several semesters.

With the SEF’s support, these threads of inquiry may extend from Delgado Alcega’s previous coursework and into tangible plans and strategies for local communities. “These research grants have offered a great opportunity to further some of the work we’ve undertaken at the GSD, and begin to transition it toward applications that could have a place in addressing specific challenges through practice,” Delgado Alcega says. “The research grant will give me the unique opportunity to transition from academia to practice in a more meaningful way in the midst of today’s uncertainty.”

There is still time to support the GSD Student Emergency Fund. A donation of any amount will have a direct impact on student research and/or emergency needs. Give today.