The city, according to Louis Kahn, arose through the establishment of institutions. By extension, he defined its “greatness” as “how sensitive [those institutions] are to renewed desire for new agreement.” Agreement, in this context, does not necessarily entail a declaration or even a conscious decision on behalf of any party. Instead, it may arise from a shared recognition of an ephemeral condition that creates “a center around which existential space is organized.” For example, Kahn believed “agreement. . . is what made the school a school, or what inspired the first room. It was an undeniable agreement that this man who seems to sense things which others don’t should be near the children so they can benefit from such a man.”

When held to this standard, most, if not all, cities lack greatness. As Foucault and others have observed, many of our institutions, from schools to hospitals, have become manifestations of and tools for power instead of sites of cooperation, dialogue, and exchange. Their architecture and design atomizes by intention, separating people into individual cells or precisely demarcated spaces where they are sequestered and observed, and thereby controlled. Our institutions, from Kahn’s perspective, have “lost their inspirational impact of their beginning and have become operational.”

For the spring 2021 studio “Small Institutions,” Roger Tudó Galí, Josep Ricart Ulldemolins, and Xavier Ros Majó—three partners at HARQUITECTES in Sabadell, Spain who served as the John C. Portman Design Critics in Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design for the semester—took Kahn as their inspiration and asked students to identify the primordial essences of various institutions: library, museum, school, temple, town hall, market, theater, hospital, swimming pool, and courthouse. By focusing students’ attention on determining and responding to the Kahnian agreement from which these institutions arose, the rituals inherent to these spaces become constitutive of their designs. In turn, this exercise illuminates how forms of communal interaction and public engagement have been lost and how they could be resuscitated. Moreover, it encourages a wholesale reconceptualization of architecture in which the plan begins with nothing, to which only the necessary is added.

For the spring 2021 studio “Small Institutions,” Roger Tudó Galí, Josep Ricart Ulldemolins, and Xavier Ros Majó—three partners at HARQUITECTES in Sabadell, Spain who served as the John C. Portman Design Critics in Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design for the semester—took Kahn as their inspiration and asked students to identify the primordial essences of various institutions: library, museum, school, temple, town hall, market, theater, hospital, swimming pool, and courthouse. By focusing students’ attention on determining and responding to the Kahnian agreement from which these institutions arose, the rituals inherent to these spaces become constitutive of their designs. In turn, this exercise illuminates how forms of communal interaction and public engagement have been lost and how they could be resuscitated. Moreover, it encourages a wholesale reconceptualization of architecture in which the plan begins with nothing, to which only the necessary is added.

“A lot of new institutions are losing the emotional conditions of architecture, becoming too functional and rational, and just working to avoid practical problems,” says Tudó Galí. “We are very much about going against these preestablished ideas and the pragmatic approach to building. Instead, we try to rediscover the platonic idea of a place and its activities.”

A novel methodological approach was fundamental to achieving these objectives, beginning with the non-architectonic meditation on agreement rather than a site-specific design problem like those typically given to students. “In general, from our experience teaching in Spain, we are always short on time in the projectural process when deciding what is really essential in architecture,” explains Ricart Ulldemolins. “We feel that students waste energy in terms of their approaches, whether academic, social, or personal. Here, we’re talking about institutions, not specifically about building, in order to put students into a very specific situation to come, from the very beginning, to the essential in architecture.”

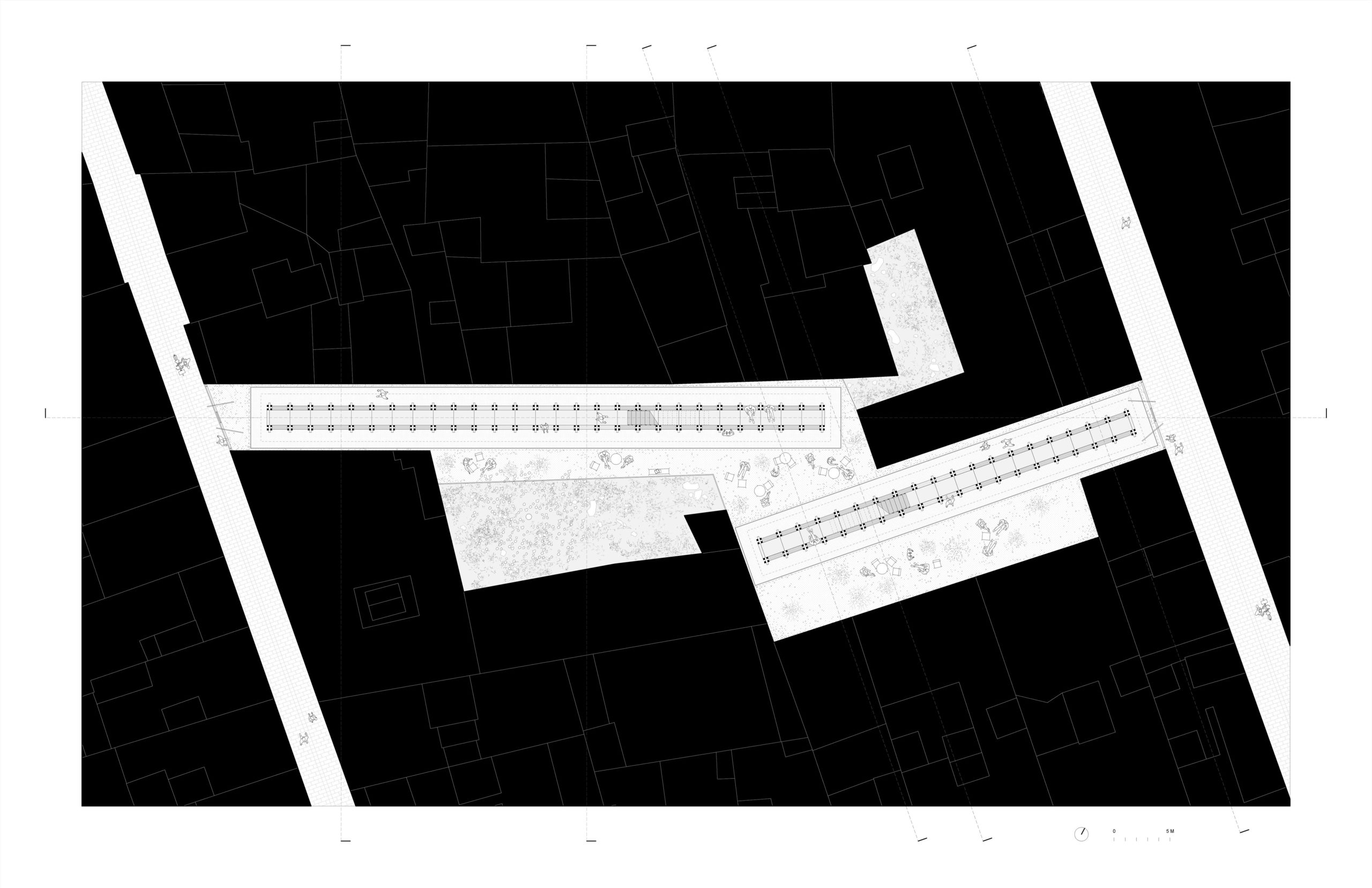

The site chosen by the trio aided their directive that the students eradicate any dependence on established forms. Located within a high-density block in the Sant Pere, Santa Caterina i la Ribera neighborhood in the oldest area of Barcelona, the long, narrow plot between party walls measures just 493 square meters. Connected to adjacent streets, it was created through the hypothetical demolition of existing buildings. Ros Majó describes their selection as “a kind of trap for the students,” as the size, especially when considered with its irregular geometry, is too small to accommodate a conventional-size institution.

More radical than its challenging dimensions, however, was that the site wasn’t disclosed until about halfway into the semester. Unbound by location or other restrictions, the students could first concern themselves solely with their unique institutions, the elemental aspects of which, the professors hoped, would become more definable with each task assigned.

The first assignment foregrounded introspection. Each student chose four photographs and built a collage as a means of creating an individual and unexpected hypothetical institution. “We didn’t want the project to focus just on the visual, but this was the fastest way to produce a personal approach rather than one based in a very abstract, general, or ambitious concept,” says Ricart Ulldemolins. With the library, for instance, Alexis Boivin (MArch ’22) fused street images with Étienne-Louis Boullée’s epic proposal for the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris. Boullée’s vaulted ceilings are here made transparent, declaratively introducing the urban into the space. At the same time, perambulators heighten a sense of the library as a free and open public institution as they evoke those browsing or just walking by the bouquinistes stalls along the Seine.

Following this warm-up exercise, the students began historical research in order to determine what parts of institutions had been retained over time, with an emphasis on typologies. “The delivery was not only to understand an evolution in history but to understand what is and is not important, and to propose what should be included in the next step of that evolution,” says Ricart Ulldemolins.

As well as providing a generative cultural-historical perspective on these institutions, the assignment, Tudó Galí explains, helped reveal the negative aspects of these spaces that have persisted. “The most boring part of the institutional idea is when it becomes a building that is repeated a lot and becomes part of an automatic system. The specificity of the design is lost,” he says. “The idea for the students was to stop this evolution and take a more open point of view, to try to produce something which defines a very specific solution and not a repetition of the same kind of buildings.” This in turn led to designing archetypes of their institutions inspired by this research—models that illustrate the main performance that takes place in each space and that define their need to exist (as opposed to site-specific concerns).

The emphasis on performance remained central in the subsequent assignment, when the site was revealed but not yet addressed as it typically would be. “We asked the students not to do a very conventional research process to understand the site but instead a short exercise that we call ‘the ephemeral project,’” says Ricart Ulldemolins. “It should be something that is not exactly a building but something that can be removed, to make the definition of the ritual stronger. It was quite a difficult moment for them, to try to expose them to the institution not as an object but as a happening,” says Tudó Galí. “Most of them work on buildings or objects but not on the activity,” adds Ros Majó.

Ricart Ulldemolins notes that not only graduate students but architects broadly have difficulty projecting the performatic part of the institution onto a site. “I think it’s a general misunderstanding of the profession to confuse the shape of the object and the object itself with the experience of people,” he says. “Our experience in a building is not exactly the design of the object. It’s the design of the experience produced by the object.”

The next step—“the primordial space,” as the professors referred to it—brought together the studies of archetype and ritual, with specific emphasis on the atmosphere of the space and haptic experiences related to temperature, materiality, natural light, and proportions. Tudó Galí believes it was the most important delivery, as it asked the students “to define what could be considered the most essential space in these institutions” and relate that to the site itself. It was the first time that the students’ assumptions of what was inherent to their institutions were brought into conversation with the material and geometrical realities of the constrained site. This confrontation stripped away additional notions of what is necessary, further distancing the designs of the institutions from the status quo.

As if this process were not surprising and confounding enough for many, the trio had a final twist—“the strategic detail”—that would further ask the students to rethink their approach to architecture in and beyond this studio. “The strategic detail is a combination of the main strategies and the smaller definition of a building,” explains Tudó Galí. “The detail cannot be understood without the general idea, and the general idea cannot be understood without the detail. In this holistic idea, everything is the same, just at a different scale or dimension. It’s not a fragment or a part that goes after the main decisions. It’s a detail that holds the possibility of changing everything.”

This directive required the students to determine an aspect of the total design from the previous assignment that was connected to the essence of the institution as developed throughout the semester. Once identified, that detail would then need to solve smaller problems through its incorporation into the space. “It started to shake everything for them a little bit, to determine if their previous ideas were a little naive,” Tudó Galí adds.

Boivin, with the library, and Diandra Rendradjaja (MArch ’22), who was assigned the market, both agreed that the methodology the professors developed forced them to question constantly how they approached their designs. “Normally in studios, you’re given a prompt at the start and work at your own pace, defining by yourself the small steps you’re taking,” says Boivin. “But the professors were precise in setting goals for us, which really helped throughout the process. Libraries are usually humongous spaces placed in flat, unbounded plots. The assignments, such as narrowing the task and focusing on the evolution of libraries throughout time, really forced the project to take a radical approach and refine what the essential qualities of a library are. The site made almost irrelevant the canonical libraries that I looked into because they wouldn’t accept or fit into this kind of space. Instead I had to achieve monumentality through small spaces or aspects of light that adjusted to those smaller spaces.”

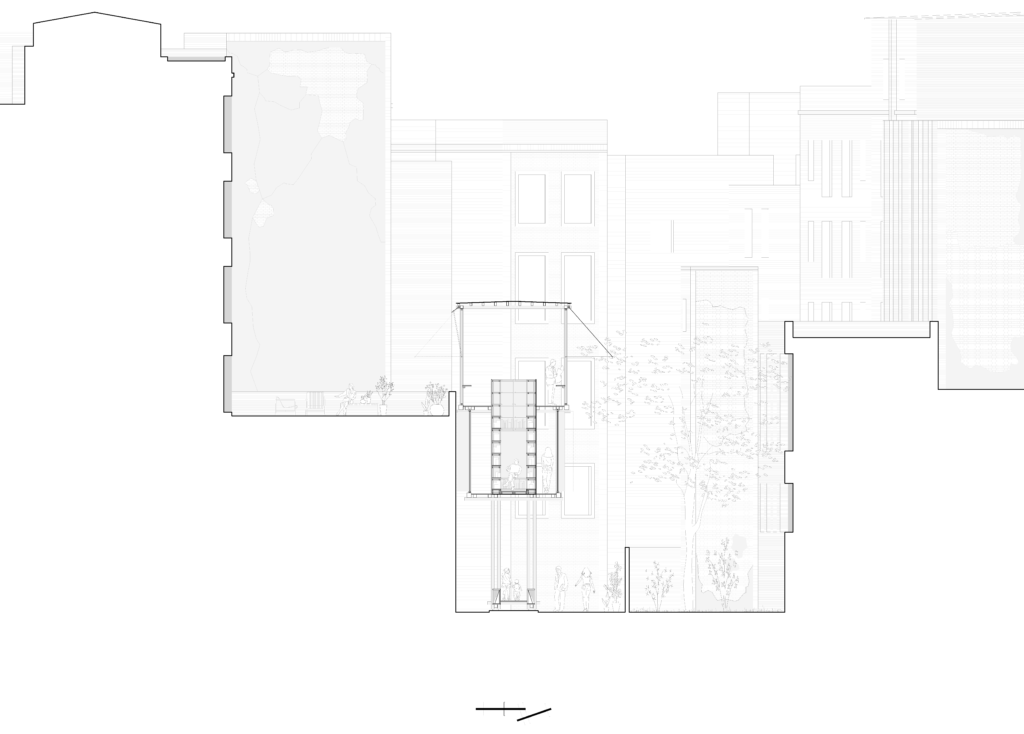

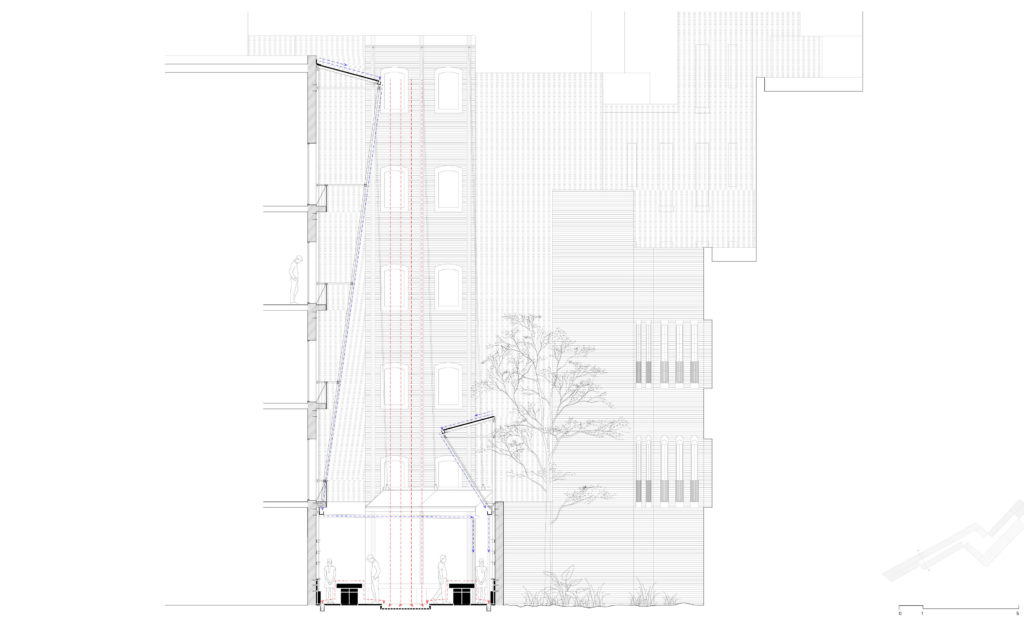

At first, Boivin sought to play with movement, with a design that carried people throughout the library, and specifically around books, in a dynamic manner via stairways and ramps. But the process encouraged a more concentrated design, built across three levels. The ground floor resembles an agora, almost empty and fluid with low bookcases on which people can sit and that encourage communal engagement. The second floor—with individual reading and storage rooms—creates a more intimate relationship with the book. Openness returns in the third floor’s grander reading room. It features a table which follows the perimeter of the room and large windows that create a sense of suspension for occupants between the courtyard and the multistory surrounding buildings. In Boivin’s words, the plan emphasizes “circulating, browsing of books, and reading as a celebration of knowledge” as well as “the activity of encountering its physical form.”

Rendradjaja also focused on public access and openness but further emphasized the site’s street-like nature. “In Barcelona, specifically in the context of the Old Town, the street is the only public ground,” she says. “Unlike the nearby Cerda blocks, which have courtyards, people here have less access to common space. The street-facing windows and balconies of neighbors are used as laundry-drying racks and plant hangers, as they are the only exterior space they have. The streets are the void between private properties. Because markets are public spaces, I felt the need to leave mine, which is almost the size of the streets around it, as empty as possible. It could be seen in multiple ways: the backyard to the surrounding buildings, a new plaza that’s half-covered, or a new courtyard that was missing from the neighborhood.”

Just as Boivin’s historical research and the initial ideas for the library it prompted became largely irrelevant, Rendradjaja experienced significant shifts in her understanding of the market. “What I thought about at the beginning of the semester didn’t transfer at all,” she says, addressing how the methodology led to an understanding that the essence of the institution should dictate form and that the site should not restrict an architect from upholding that essence as primary. “Roger, Xavi, and Josep’s approach to the studio and in their work is always to try to find the most precise solution—not in the sense that there’s only one ultimate answer but finding one out of many possibilities to do something that’s simple, straightforward, and smart. It’s about doing something with very minimal effort but maximum effect,” she explains. “So the ephemeral exercise, which for me was the most eye-opening, was about discovering the ritual of an institution—the activity, not the building itself or its construction. In my case, that was market exchange and maintenance, and the minimum elements you need in order for that to happen. That was the moment I realized what the studio was about, and I thought it was very helpful throughout the semester.”

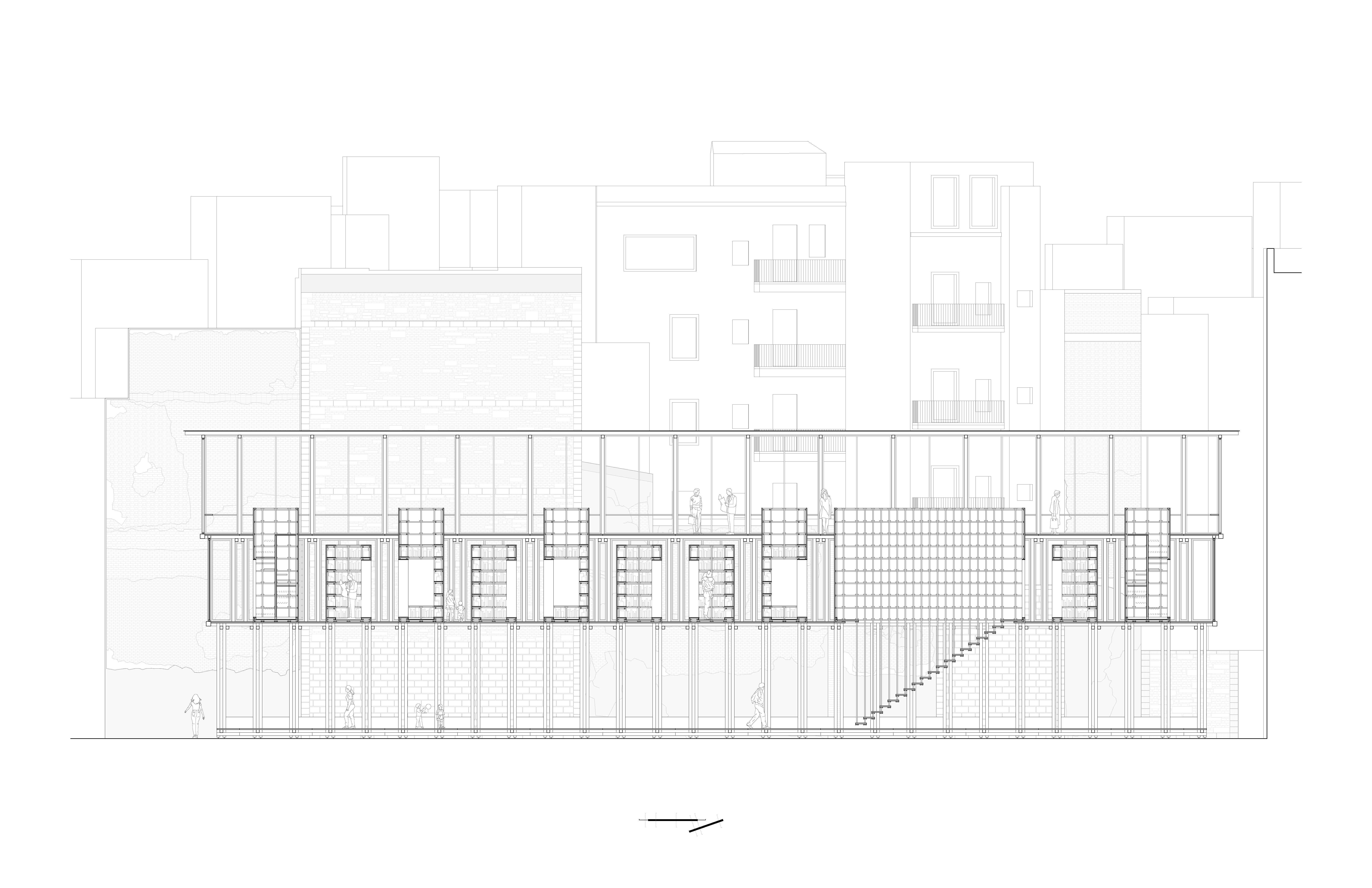

Rendradjaja’s design reclaims the market from the enclosed hall, which she characterizes as “selective of its merchants and detached from the public surroundings as it forms a private entity,” and returns it to the open-air street as a “universal public space.” The design’s central facet is “a series of roofs, held by engaged columns that are structurally supported by and dependent on the existing walls.” These hang over the rows of stone tables permanently installed on the ground. At different elevations, they enable palpable light and shadow changes. Situated much higher than in traditional markets, they also instill an awareness of being within the city rather than confined within a form of transplantable architecture.

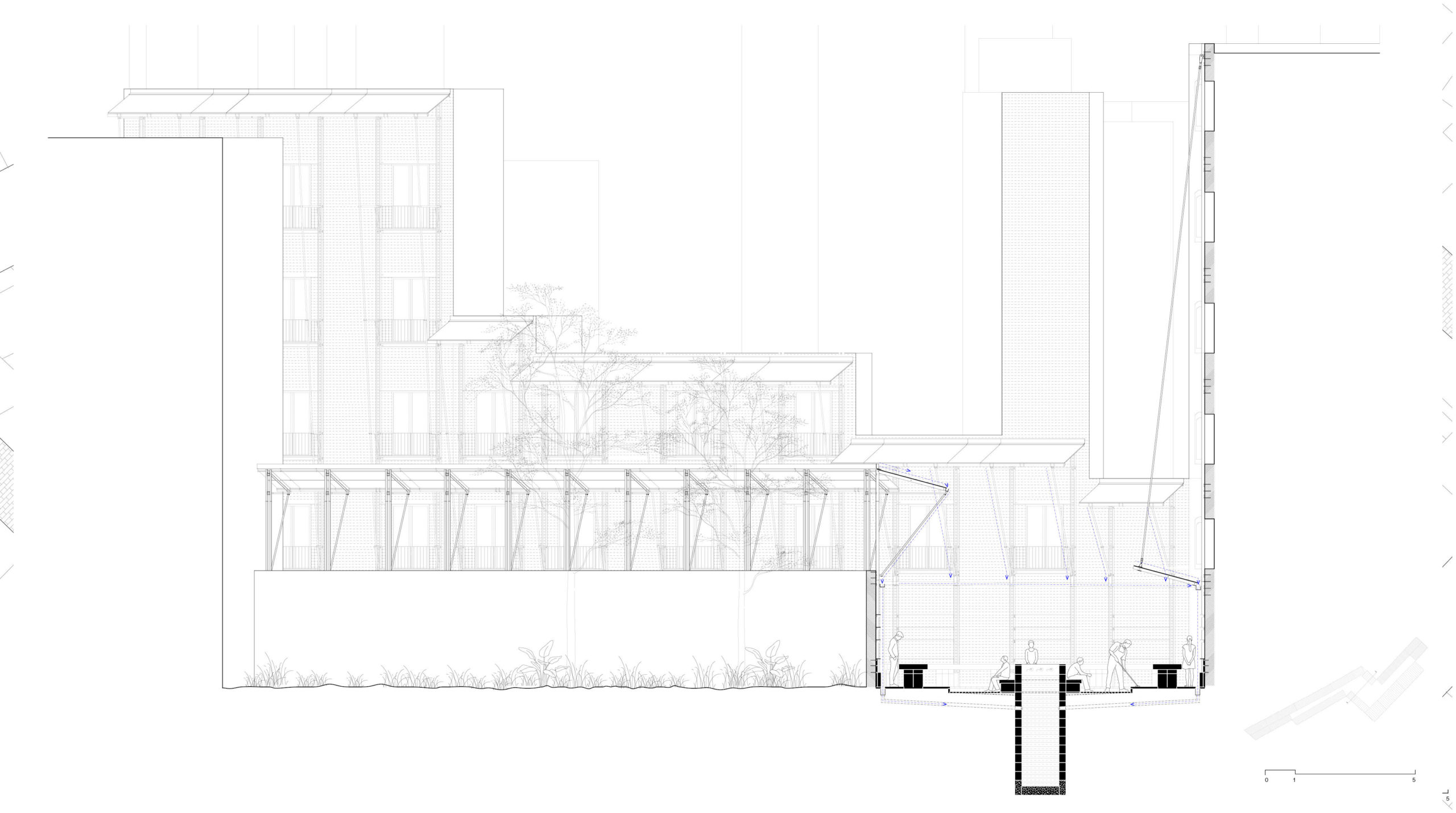

Arguably most crucial though, in terms of the studio and the professors’ hopes for its methodology, is how these roofs also fulfill the “strategic detail” assignment. “The strategic detail is meant to be a precise response to something that facilitates the performance of your institution,” Rendradjaja says. In her case, that performance concerns water, a required resource for a market. “The roofs evolved from being protection from rain and for shade to being water-collection devices. In the final assignment, the structure that holds them up in compression are at the same time pipes that move water down from the gutter to a collection tank. In order to separate rainwater from the used water of the market, two independent routes are installed, sectionally. Both routes culminate at the center point of the project, where a tank underground stores water throughout the year and reveals itself aboveground in the form of a resource fountain.” Thus the roofs, through their multifunctionality as infrastructure for a water system integral to the institution, bring balcony and market together in a holistic design.

The surprises experienced by the students at each step in the studio somewhat echo the need for shocks, gentle or otherwise, in our large-scale understanding of institutions. What is conventionally considered “institutional” refers to material facets—often linked to power rather than style—that become unoriginal through their repeatability and which reduce the institution to these typological details. The essences of these institutions—their “invisible conditions” as framed by Tudó Galí, Ricart Ulldemolins, and Ros Majó—are ephemeral, however, and therefore resist codification.

To design with Kahn’s formulation of the agreement as one’s impetus is a rebuke against a society that has forgotten why our institutions exist and the rituals at their genesis. The only demand it makes is the continual questioning of the status quo and the stripping away of the superfluous. “It’s necessary to demolish the conventional building of the institution in order to understand what is essential to that institution,” says Ricart Ulldemolins. “The success of the course, for me, was that most students discovered this by themselves.