“More light!” Goethe reportedly said on his deathbed in 1832. At that time, the outer walls of buildings were load-bearing, so they tended to be thick and windows were necessarily small. In the decades after Goethe’s death, structural advances in architecture meant that these outer walls could be relieved of their weight; designers could increase window sizes and admit more light into building interiors. Glass came to be associated with the luxury of being able to pay for the most current building technologies. In the 20th century, this trend of increased transparency evolved into the curtain wall—a building’s outer envelope of sheer glass. Office buildings especially adopted this facade to signal participation in the high-tech world of global capitalism. Though curtain walls tend to look a lot alike, each carries an “aura”: an association with power.

Bringing in “more light,” unfortunately, has become associated with another kind of death: that of the planet. With sunlight comes heat, and the cooling systems that are needed to counteract that heat—aside from being costly—consume more energy and generate even more heat, both of which contribute further to global warming. Glass is also notoriously inefficient with insulation values, increasing energy loss. Now that so many skyscrapers feature all-glass curtain walls, the cumulative environmental effect has become troubling. In 2019, New York City responded with Green New Deal legislation that imposes severe restrictions on curtain walls in future construction. Existing large buildings (25,000 square feet or more) will be required to undergo redesign or retrofitting to reduce energy use, rendering them more environmentally sustainable.

Enter architect Jeannette Kuo, who this past semester taught “THICKER,” a seminar at the GSD about the curtain wall phenomenon. The title came from the possibility that alternatives to the all-glass curtain wall might emerge from the critical study of older and often “thicker” facades. Kuo, who cofounded the Karamuk Kuo firm in Zurich in 2010, had noticed that issues of sustainable facades have yet to be addressed in university curricula from a design theory perspective. Courses often focus more on technological solutions rather than greater conceptual, cultural, and design underpinnings. She imagined that the seminar could be a model for filling this gap in architectural education and practice.

The motivation for the course has roots in Kuo’s personal history. She watched as glass skyscrapers colonized the built landscape in Indonesia, the tropical country where she grew up, as well as in even hotter, sunnier areas, such as Dubai and Egypt. She noticed that global corporations were using all-glass facades to promote an image of economic advancement tied to the West. Yet the design choice ignores local contexts and is obviously unsustainable: cooling costs in desert climates are immense. Kuo wondered how the worldwide proliferation of these “heat magnets” could be addressed through a shift in architectural culture. She theorized that the curtain wall would remain an automatic design choice in a corporate landscape still driven by global capitalism until it becomes possible to craft alternative images of progress and even alternative structures of power.

Instead of leaving the outside of the building for last, what would happen if the building were designed from the outside in?

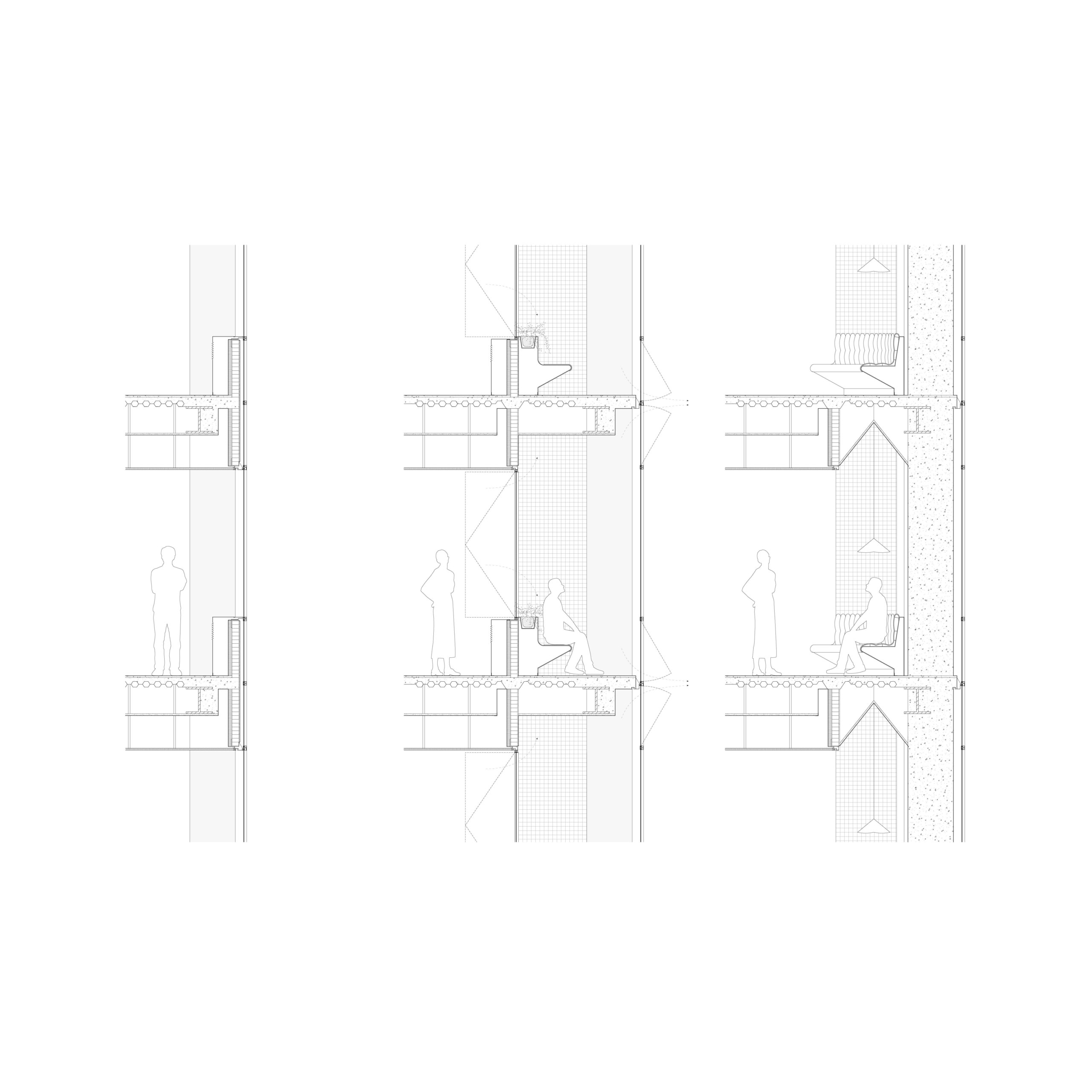

The curriculum for “THICKER” was not a technical survey of “green design” possibilities, but rather a discussion-based dive into theoretical and historical material. Kuo blended environmentalism with aesthetics and cultural studies to reconsider facade design altogether. Instead of leaving the outside of the building for last, what would happen if the building were designed from the outside in? If the pressing environmental issues related to the building envelope were treated as a design opportunity, the reconceptualization of the curtain wall could affect the entire building.

Kuo posed several questions to guide the inquiry: What have we found so seductive in the curtain wall’s transparency and reflectivity? How can we understand and call into question this cultural conditioning? Given the environmental concerns, what technical and visual strategies might be gleaned from earlier, “thicker” facades, and why are these older solutions now less popular? What kinds of cultural work does the building’s envelope perform? Finally, how might a facade which integrates cultural and aesthetic details with sustainable technical solutions propose creative visual and conceptual responses to global capitalism?

The course was conducted as a theory and design seminar in a hybrid format. Discussions were open-ended as Kuo encouraged a think-tank atmosphere. Some particularly engaging topics included contrasting the hermetically sealed glass envelope with design strategies that function in conversation with local social contexts. Also, whose vision of “progress”—and what kinds of “power”—does the all-glass curtain wall signify? The class interrogated the value of light in Western mythologies, given that in many non-Western cultures, it has historically been shadow and not light which gives comfort. How might prioritizing shade present a new view of strength?

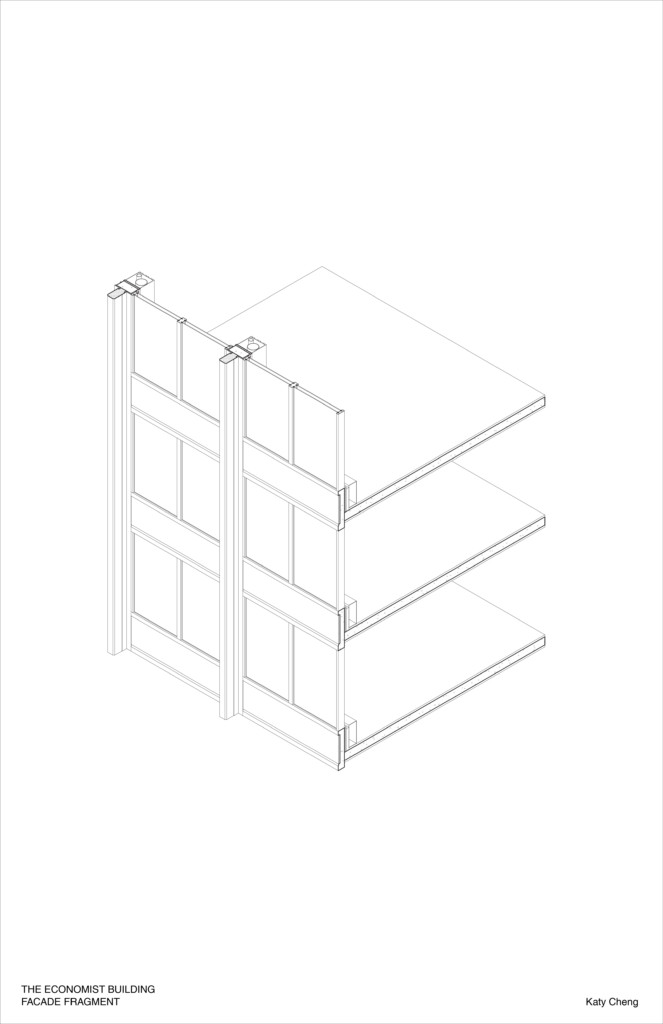

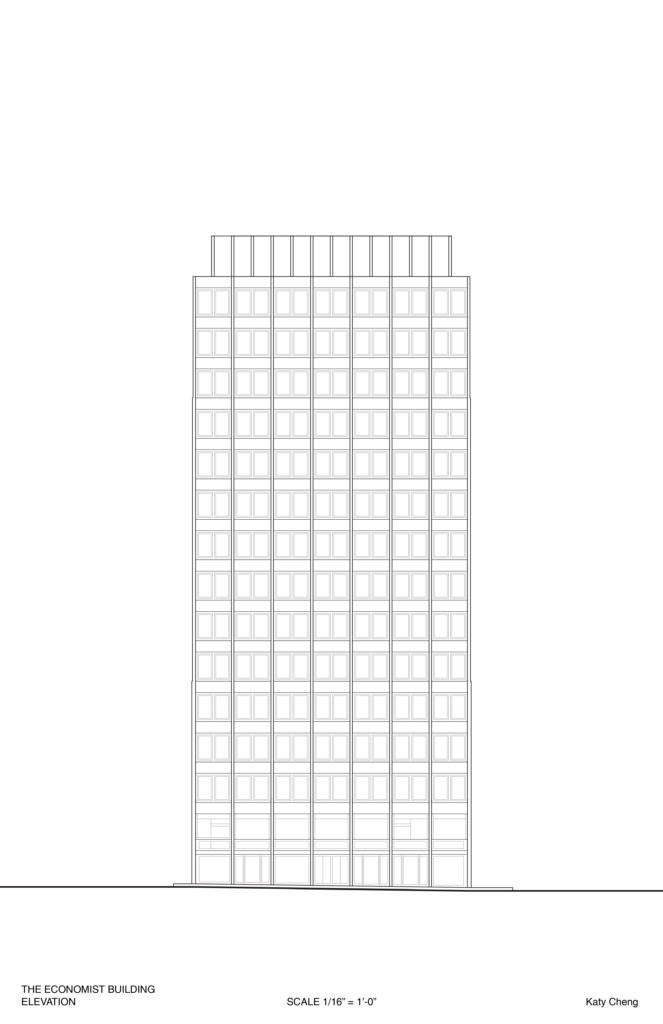

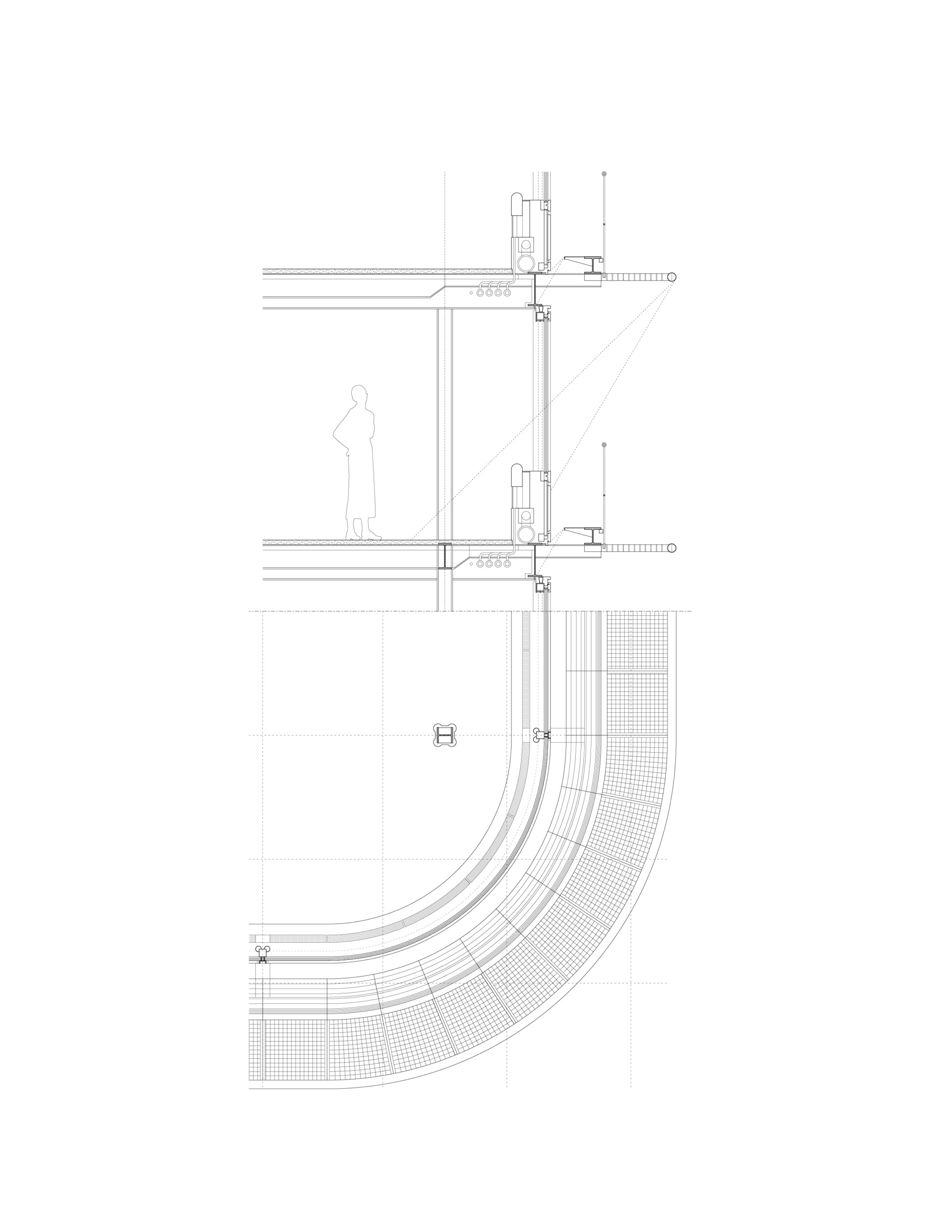

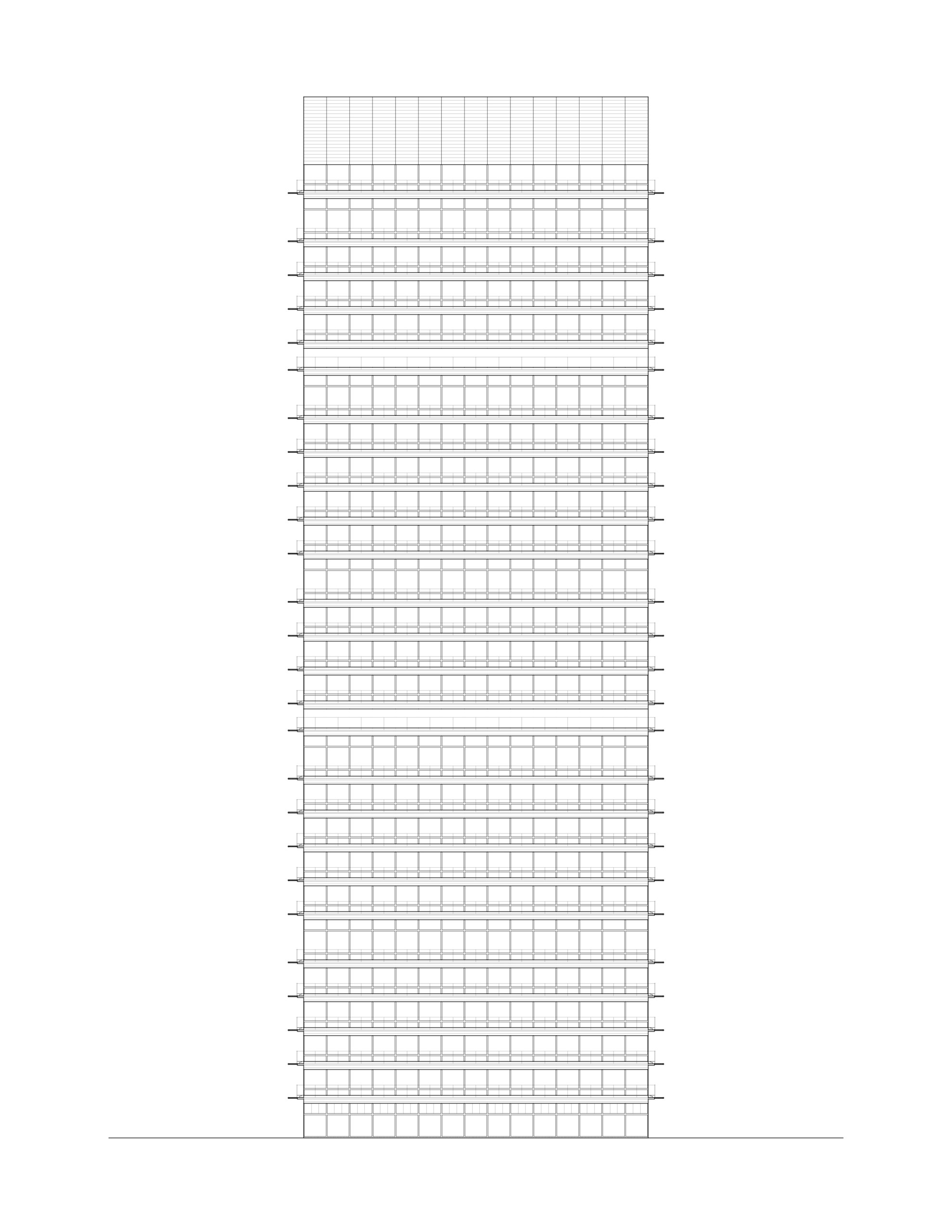

Reading selections investigated theoretical contexts and case studies starting in the late 19th century, when Louis Sullivan was insisting that “the loftiness of the tall office building must be . . . made the dominant chord in the design.” Studies of buildings with classic curtain walls were contrasted with moments in the mid-20th century when some buildings’ more sustainable facades could be models for challenging the curtain wall, though these projects often were not recognized for the contributions they could offer. The 1962 Economist Building in London, for instance, is remembered for responding to the urban site with a multi-building campus featuring a public plaza, but Alison and Peter Smithson’s facade design featured mullions that channel rainwater flows. Paul Rudolph’s Blue Cross Blue Shield Building in Boston, also completed in the early 1960s, similarly features air distribution through prefab concrete “mullions.” Many of Le Corbusier’s postwar buildings featured brise-soleils and even pioneered the double-glazed “mur neutralisant,” which attempted to address the low insulative performance of glass. He had famously opposed the all-glass curtain wall that was installed at the United Nations headquarters in New York. But a “thicker” facade need not mean a heavier one. The more recent BBVA Tower in Madrid (1981) offered the class a model for using extended balconies to shade a building from the bright Spanish sun while at the same time presenting an image of lightness.

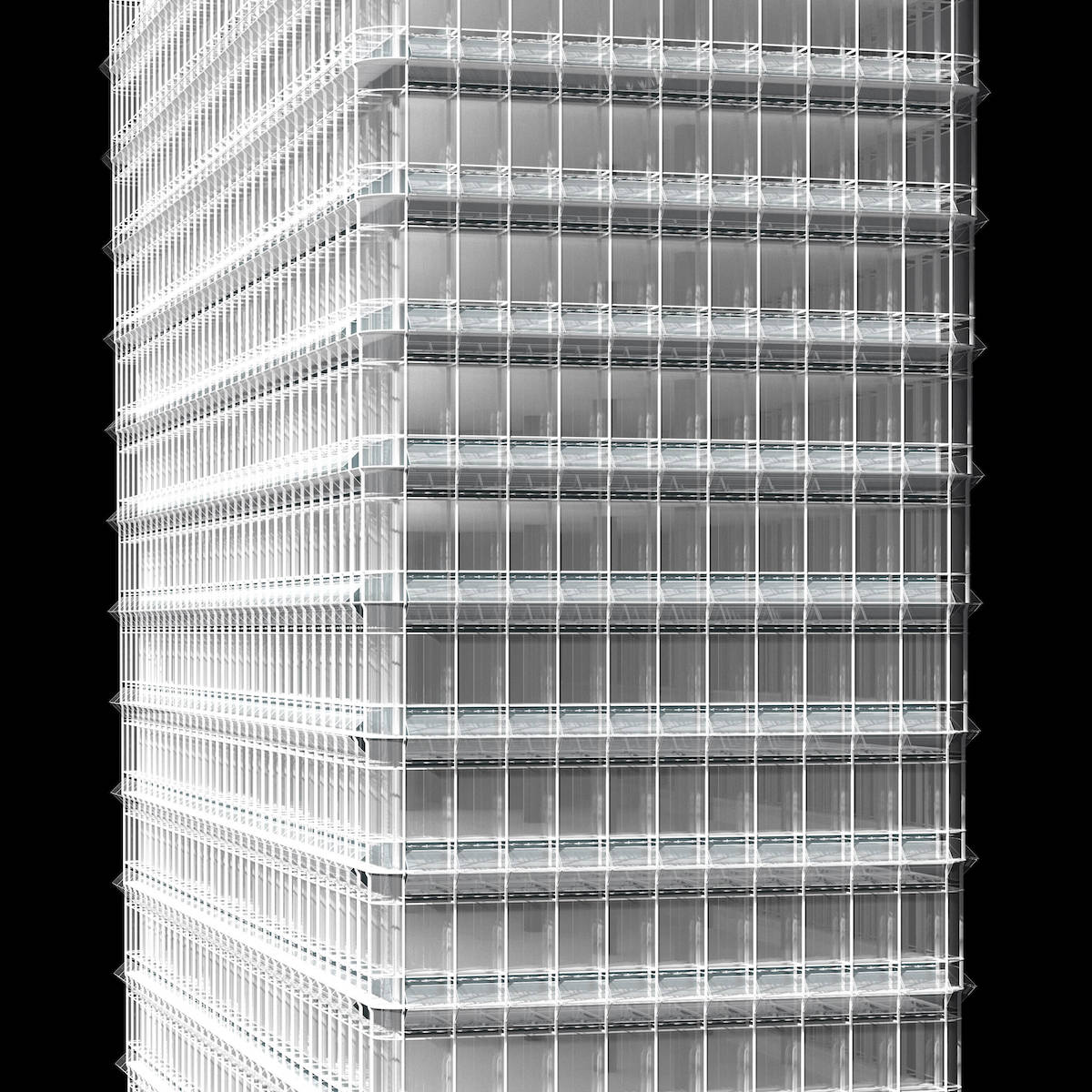

All of these histories and frameworks informed students’ proposals, in the last few weeks of class, for redesigning the Lever House in Manhattan. This choice of a site was thoroughly strategic. The building was declared New York City’s first modernist landmark in 1982; it had been the city’s first commercial building to use an all-glass envelope when it opened in 1952. The building at 390 Park Avenue, about a dozen blocks north of Grand Central Station, still houses the US headquarters of the international company now called Unilever. It has undergone updates to its iconic facade before, and there are plans for another redesign. The company, which spans many types of product brands beyond its original soap, has a clear commitment to sustainability in its buildings worldwide, and now of course it will be subject to New York City’s new energy guidelines for large buildings.

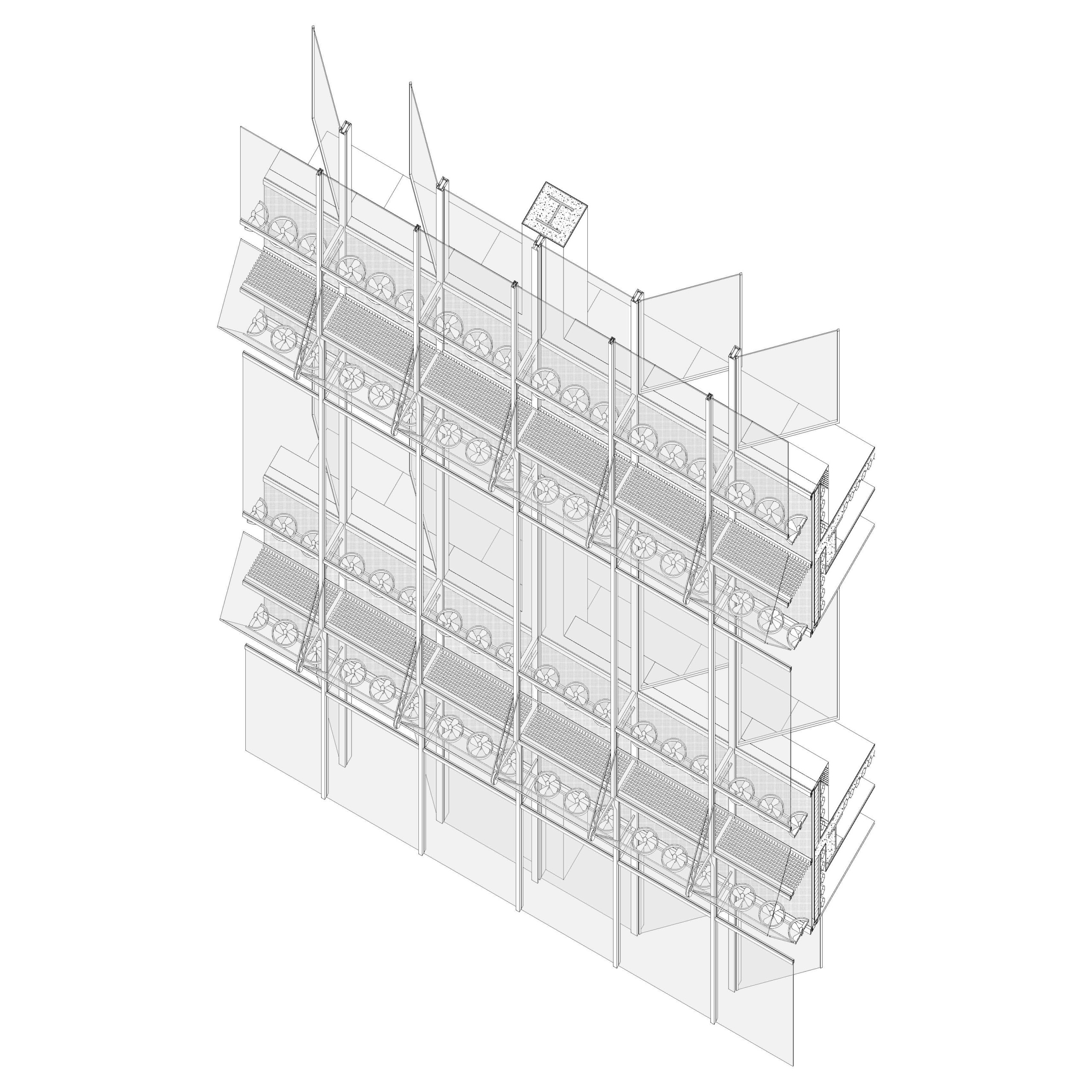

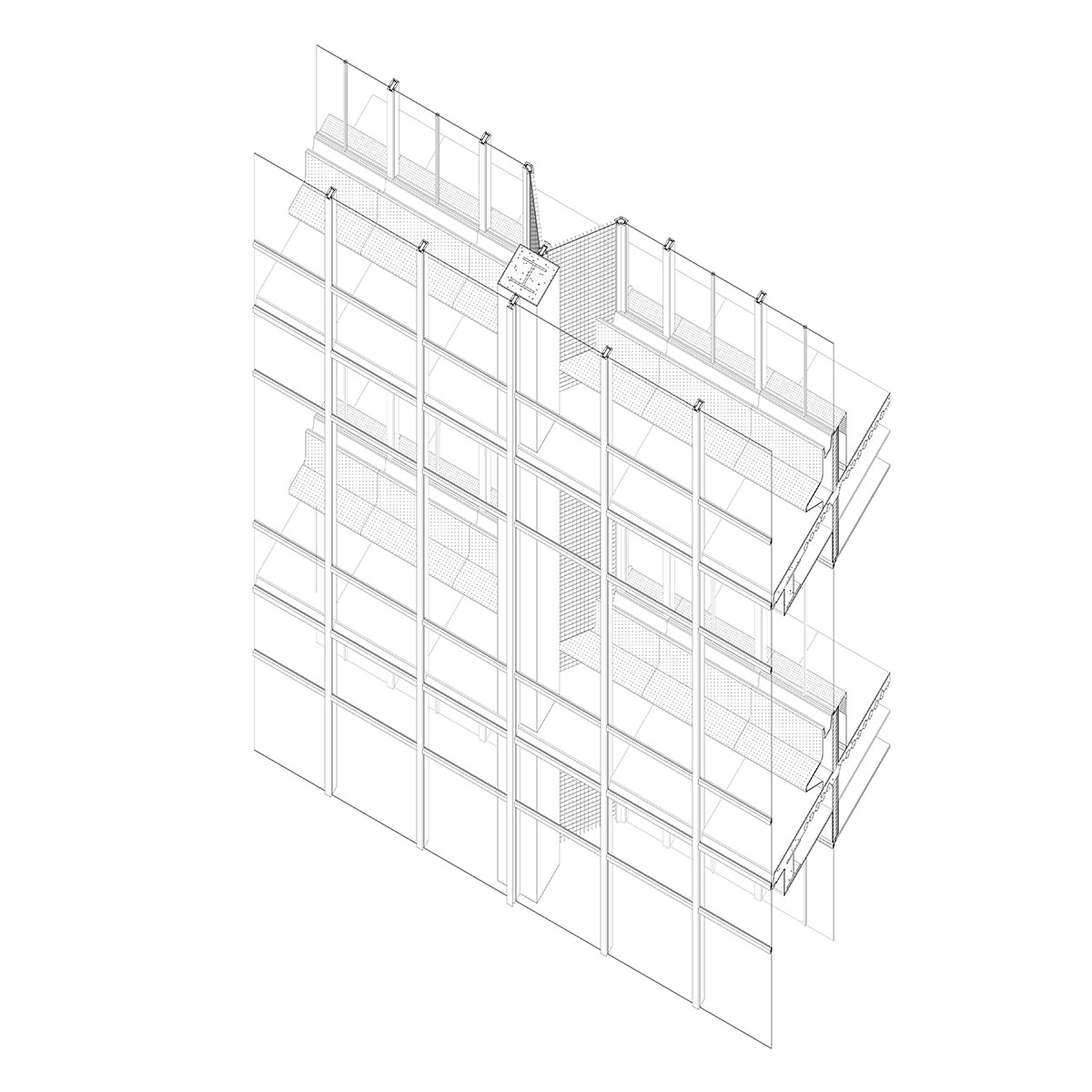

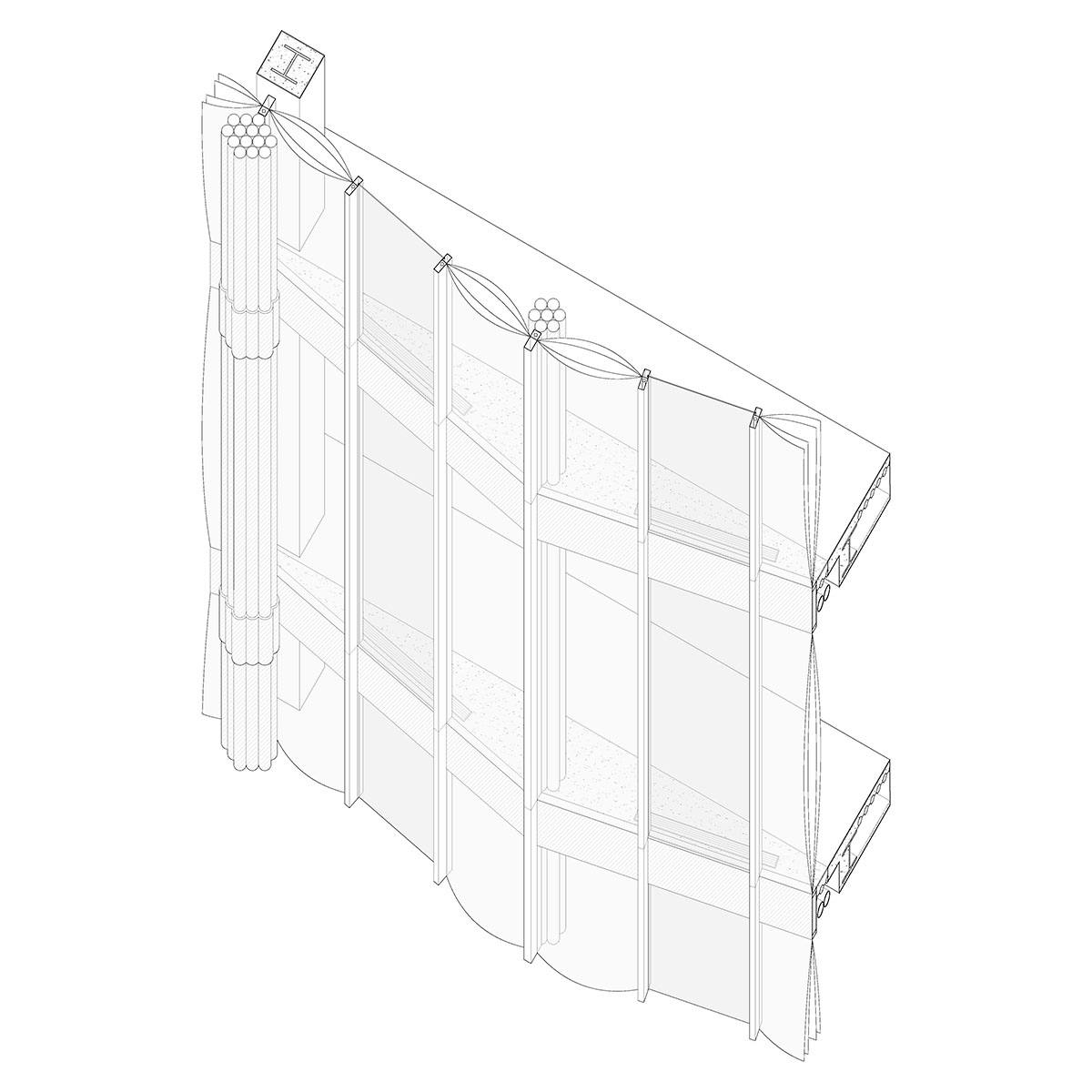

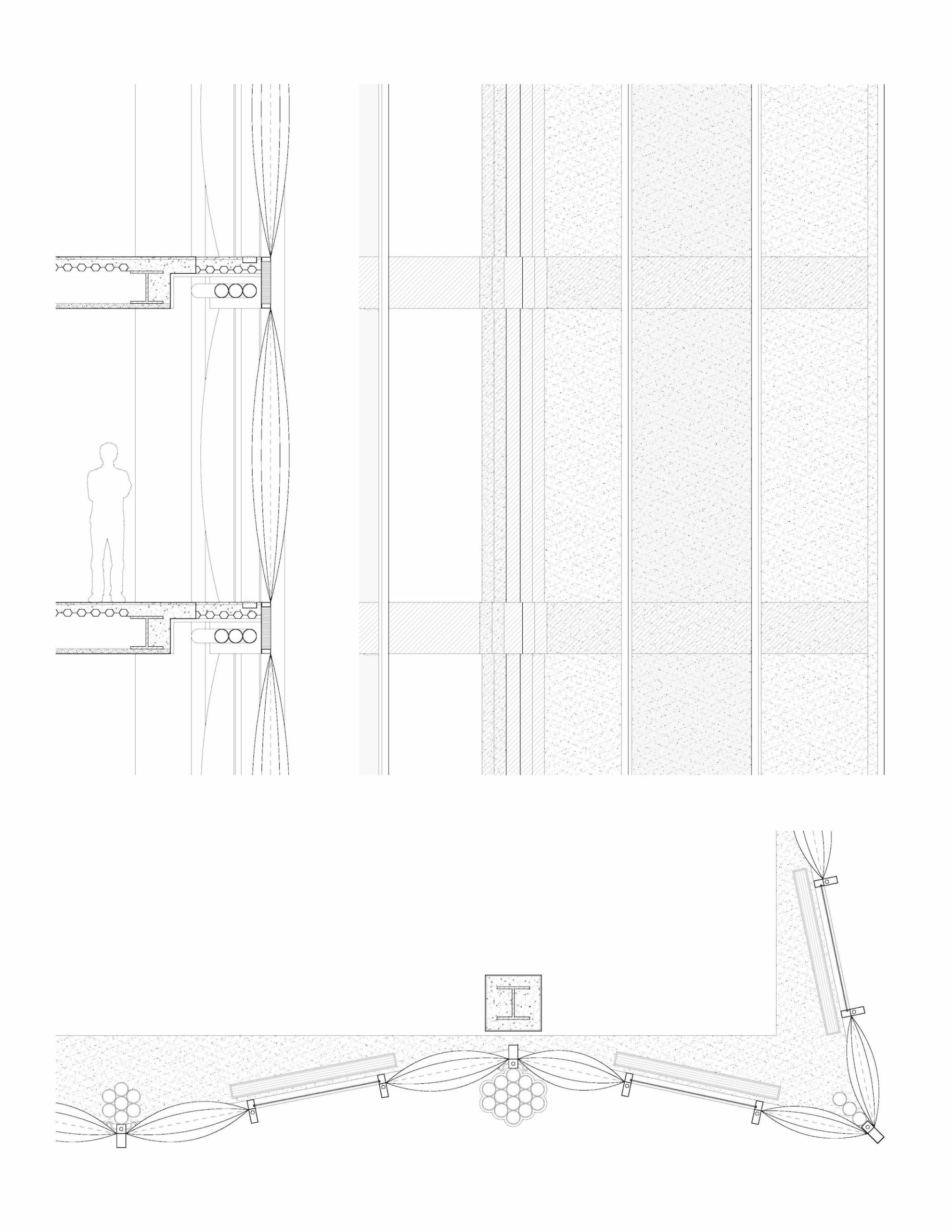

Students imagined various approaches to redesigning the facade. Yet the situation was also technically constrained: the enormity of the surface area and the building’s height meant that students couldn’t simply block light with heavy materials such as brick. The group researched the building, site, local environmental conditions, and corporate history, and each student developed a design proposal based on an aspect of the architectural situation that they found particularly compelling.

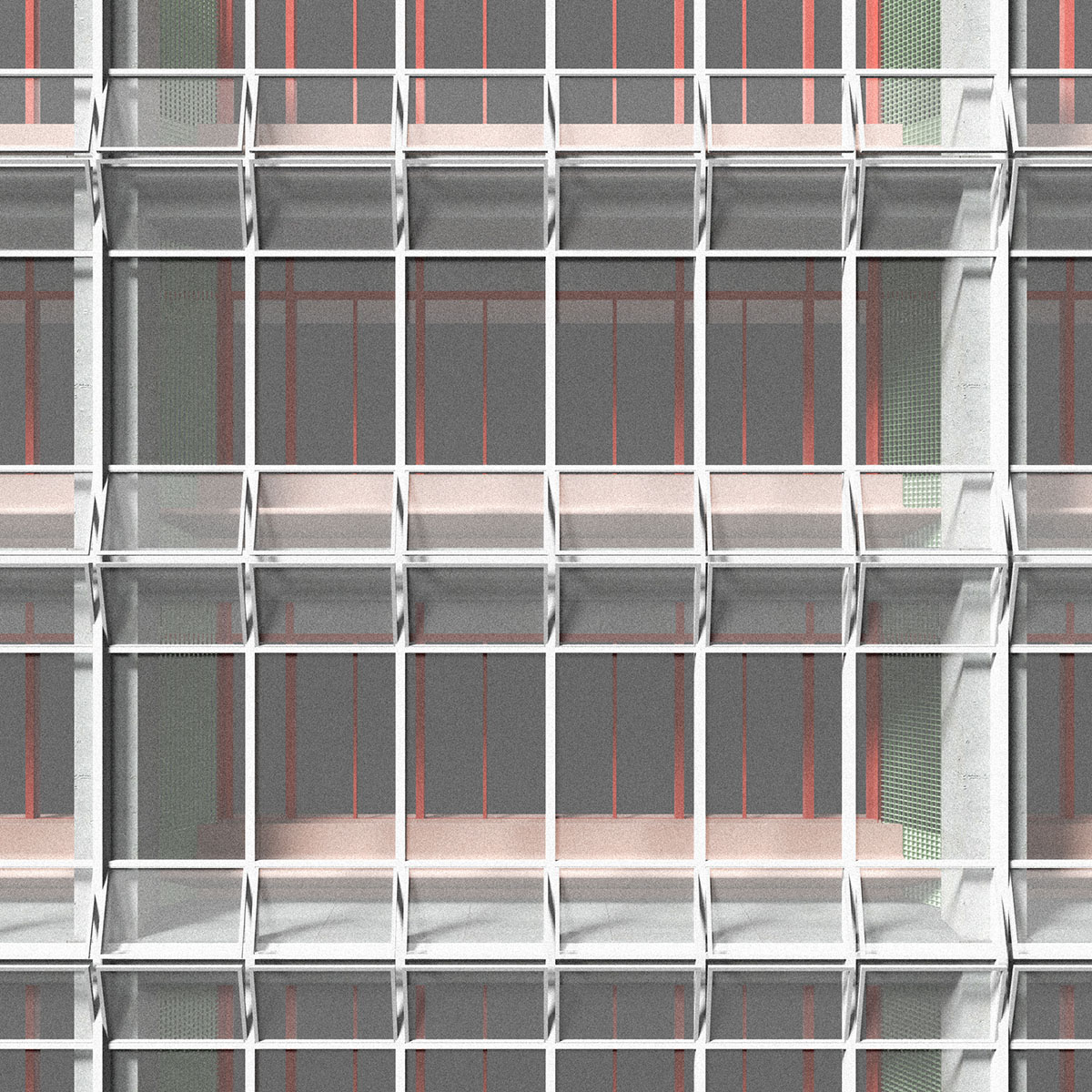

Several students attended closely to the aesthetics of Gordon Bunshaft’s original facade design for the Lever Building, which included an all-over grid and a color scheme to match the palette of the company’s signature soap packaging. Others proposed an outer layer of shading in the form of wraparound balconies, especially on the building’s sunny south side. Balconies had the additional benefit of incorporating the breaks that had become a recommended part of work culture since the building’s original design. Some students used in-depth studies of wind patterns to create subtle interventions in air circulation and to harvest wind energy; others looked to the building courtyard’s original landscape design by Isamu Noguchi to inspire ideas that would involve plant life. Inevitably, many designs featured light-blocking panels such as louvers, sails, retractable awnings, and moveable wall elements. These all had the challenge of making sure daylight could penetrate the building envelope while still creating reliable heat reduction and energy savings.

Student projects succeeded in suggesting new possibilities and visual languages for environmentally integrative facade design. Given the environmental damage that the all-glass curtain wall can cause, Kuo’s course demonstrated that there is no reason for remaining entrenched in this design cliché. And as we face an uncertain economic future—“Extreme capitalism is over,” notes Kuo—this course showed how the reconceptualization of the curtain wall could advance new images of corporate health as well as new paradigms for sustainable design.