“Plains and Pampa: Decolonizing ‘America,’” by Ana María León Crespo—Excerpt from Harvard Design Magazine

It is a common trope for scholars from South America, Central America, and the Caribbean to argue that America is the continent, and not the country. It is less common to consider what the idea of America as a territorial unit might imply. Thinking about the region as a whole prompts us to notice similar processes and shared politics, particularly in reference to decolonization and decolonial discourses.[1]

Indigenous scholars in settler colonial countries such as Australia, Canada, and the United States have advanced theories of decolonization as the rematriation of Indigenous land and life. [2] In contrast, Latin American decolonial theorists—known as the Modernity/Coloniality group—have focused their critique on the role of colonialism in the construction of modernity.[3] Both terms stem from the discourse on resistance and struggle by Martinique intellectuals Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon, whose argument cuts across these groups and highlights the role of Black studies within both—a complicated intersection that I’m unable to address in this piece. [4]

Given the increased use of these terms, it is important to understand the slippage between decolonization and decoloniality, which have in many cases been conflated. More urgently, both concepts have often been reduced to apolitical notions of increased geographical coverage, eloquently summarized by Anni Ankitha Pullagura as the notion of “making empire more inclusive.”[5] Rather than cede ground to this depoliticized inclusion, the challenge in thinking through the idea of decolonizing “America”—or any territory for that matter—is that of centering the voices excluded by empire. Land and its inhabitation, occupation, or possession plays a key role in this conversation. The way we situate ourselves within it has the potential to redefine the history of architecture as well as architecture itself.

Decolonization points to the impact of settler colonialism—a type of colonialism in which the Indigenous population is replaced by an invasive settler society. Meanwhile, decoloniality is less geographically determined, and seeks to critique colonialism as an epistemic framework whose violence is present in all locations, even in colonizer regions. In doing so, decolonial theory can sometimes place too much emphasis on Eurocentrism, eliding the internal conflicts highlighted by what decolonization theory describes as the “entangled triad structure of settler-native-slave.” [6]

Thinking through this structure, decolonization points to the multiple ways in which the development of settler colonialism—in countries such as the United States but also, I argue, Argentina—is enmeshed in processes of capital extraction that have racialized populations and depleted the land. Complementing this discourse, decoloniality reveals the ways in which these processes are constitutive of modernity itself, understanding the European arrival to America as a component of the acceleration of global commerce that links modernization, capitalism, and empire.

A brief example highlights how comparing these different histories through these combined theoretical frameworks can reveal some blind spots. The independence movements in both the US and Argentina were led by European descendants eager for political independence from Europe and more economic power. While in other countries Indigeneity was strategically appropriated in the formation of national identity (particularly in countries with monumental Indigenous architecture, such as Mexico and Peru), in settler colonial societies Indigenous peoples were seen as a threat to the construction of the nation.[7] Thus upon gaining independence, both the US and Argentina targeted the Indigenous populations that inhabited what they conceived as their land, resulting in a series of extermination campaigns with the specific objective of appropriating Indigenous territory.

Human and non-human agents have inhabited the continent for millennia, benefitting from mutually sustaining relationships. The aggressive hunting of the bison in the US, and the introduction of non-Indigenous species such as cattle and swine in both countries, radically transformed this landscape.[8] The replacement of local staples with more profitable, non-Indigenous crops echoes the aggressive replacement of Indigenous people including Anishinaabe groups in the north and Mapuche, Aymara, and other groups in the south. Taken together, these are the processes of settler capitalism, the primary goal of which is the transformation of land into a site of extraction. The role of the US Plains and the Argentinian pampas in the construction of these countries’ national identities highlights how the mythification of the land is a component of its commodification. These and subsequent histories of land dispossession, occupation, extraction, and capital constitute our American modernity.

Decolonization points to the status of America as occupied land, and decoloniality reveals the role of this occupation in the production of modernity. Understanding the intersection between the two allows us to turn toward new relationships with the land—relationships that might dismantle settler frameworks and center previously silenced voices. While decolonization and decoloniality have different, overlapping definitions, it is their shared politics that suggest a different approach to land and its history. Nick Estes, historian and citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe, titled his groundbreaking book on Indigenous resistance with the beautiful words Our History Is the Future. [9] Indeed, the histories we learn, research, and teach open up other futures. By studying the environments that peel away settler narratives of buildings and landscapes, we can open the way toward decolonized and decolonial futures.

Ana María León Crespo is an architect and a historian of objects, buildings, and landscapes. Her work traces how spatial politics shape the modernity and coloniality of the Americas. León teaches at the Harvard GSD and is cofounder of several collaborations laboring to broaden the reach of architectural history.

[1] The Decolonizing Pedagogies Workshop (2018—) and the Settler Colonial City Project (2019—), both co-founded with Andrew Herscher, have been key in understanding these topics. The students of “Histories of Architecture Against” (Fall 2019) at the University of Michigan helped me think through these categories. A longer, earlier version of this text was originally presented in Mexico City at the CIHU congress in Fernando Luiz Lara and Reina Loredo’s panel “Rompiendo Fronteras Coloniales.” I am thankful to their call to think about these histories.

[2] See Eve Tuck (Aleut) and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1:1 (2012): 3.

[3] The Modernity/Coloniality group includes the work of Walter Mignolo, Aníbal Quijano, Ramón Grosfoguel, Arturo Escobar, Fernando Coronil, Javier Sanjinés, Enrique Dussel, and others. The project starts roughly in 1998 and includes both collective and individual books.

[4] Aimé Césaire, Discours sur le colonialisme (Paris: Éditions Reclame, 1950) and Frantz Fanon, Les damnés de la terre (France: Éditions Maspero, 1961). For more on the intersection between Black and Native studies see Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019).

[5] Anni Ankitha Pullagura in the introduction of her recent CAA panel with Anuradha Vikram, “A Third Museum is Possible: Towards a Decolonial Curatorial Practice.” Collegiate Art Association Annual Conference, 14 February 2020, Chicago, IL. In working through these ideas I’m also indebted to Ananda Cohen-Aponte’s beautiful response to “Working with Decolonial Theory in the Early Modern Period,” CAA 13 February 2020, Chicago IL.

[6] Tuck and Yang, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” 1. Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui has made an eloquent critique of the Modernity/Coloniality group from an Indigenous perspective. Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, “Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: A Reflection on the Practices and Discourses of Decolonization,” South Atlantic Quarterly (2011), 111(1): 95-109. For a conversation across these differences, see “Thinking and Engaging with the Decolonial: A Conversation Between Walter D. Mignolo and Wanda Nanibush,” in Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, no. 45 (Spring/Summer 2018): 24-29.

[7] This is not to say that Indigenous peoples have not been under attack in societies that do not strictly fit settler colonial frameworks.

[8] For an environmental history after settler occupation in New England, see William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983).

[9] Nick Estes, Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (London: Verso, 2019).

This piece was originally written for, and printed in, Harvard Design Magazine #48: “America ,” 2021

Welcoming 2022–2023 Pollman Fellow Emmanuel Kofi Gavu

The Harvard Graduate School of Design is pleased to welcome Emmanuel Kofi Gavu as the Pollman Fellow in Real Estate and Urban Development for the 2022–2023 academic year.

Gavu (Dr.-Ing.) is a senior lecturer at the Department of Land Economy, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, Ghana. He completed his PhD in Spatial Planning at the TU Dortmund University in Germany. He also holds an MS in GIS for Urban Planning from the University of Twente in the Netherlands and a BS in Land Economy from KNUST Ghana.

Gavu is primarily interested in applications of GIS in urban management, real estate, and housing market analysis. He has published in the areas of hedonic modeling, housing market dynamics, and real estate education. A short-term consultant for the World Bank, Gavu is also a board member of the African Real Estate Society (AfRES), serves as chair of the Future Leaders of the African Real Estate Society (FLAfRES), and is a member of the Ghana Institution of Surveyors (GhIS). At the GSD, Gavu plans to work on the pricing of residential rental housing units in the Global South during global shocks, including pandemics. His goal is to provide information to housing market stakeholders that will enable them to understand the operations of the rental market during global shocks and to offer policy directives based on findings.

One of the fellowships and prizes administered by the GSD’s Department of Urban Planning and Design, the Pollman Fellowship was established in 2002 through a gift from Harold A. Pollman. It is given yearly to an outstanding postdoctoral graduate in real estate, urban planning, and development who spends one year in residence at the GSD as a visiting scholar.

Michael Meredith and Monica Rhodes awarded American Academy in Rome’s 2022–2023 Rome Prize

Michael Meredith (MArch ’00) and Monica Rhodes (LF ’22) have been named winners of the 2022–23 Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome (AAR). These highly competitive fellowships support advanced independent work and research in the arts and humanities. This year, the gift of “time and space to think and work” was awarded to 38 American and four Italian artists and scholars. They will each receive a stipend, workspace, and room and board at the academy’s 11-acre campus on the Janiculum Hill in Rome, starting in September 2022.

Rome Prize winners are selected annually by independent juries of distinguished artists and scholars through a national competition. The 11 disciplines supported by the Academy are: ancient studies, architecture, design, historic preservation and conservation, landscape architecture, literature, medieval studies, modern Italian studies, music composition, Renaissance and early modern studies, and visual arts.

Michael Meredith has won the Arnold W. Brunner/Katherine Edwards Gordon Rome Prize in the area of architecture. Along with his partner, Hilary Sample, Meredith is a principal of MOS, an internationally recognized architecture practice based in New York. Meredith is professor and assistant dean of Architecture Design at Princeton University. His writing has appeared in Artforum, LOG, Perspecta, Praxis, Domus, and Harvard Design Magazine. Meredith previously taught at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, the University of Michigan, where he was awarded the Muschenheim Fellowship, and the University of Toronto.

Monica Rhodes has won the Adele Chatfield-Taylor Rome Prize in the area of historic preservation and conservation. Prior to the Loeb Fellowship, she led efforts at two of the largest national organizations focused on historic preservation and national parks—the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the National Park Foundation. During her tenure at the National Trust, Rhodes developed the first national program designed to diversify preservation trades. Rhodes’s work has been featured on PBS NewsHour and in the Washington Post, Huffington Post, and in a feature on women in the preservation movement in Essence magazine.

Established in 1894, the American Academy in Rome is America’s oldest overseas center for independent studies and advanced research in the arts and humanities. It has since evolved to become a more global and diverse base for artists and scholars to live and work in Rome. The residential community includes a wide range of scholarly and artistic disciplines, which is representative of the United States and is fully engaged with Italy and contemporary international exchange. The support provided by the academy to Rome Prize winners, Italian fellows, and invited residents helps strengthen the arts and humanities.

For information on this year’s winners, please visit 2022 Rome Prize Fellowship Winners and Jurors.

Celebrating Recipients of the 2022 President’s Innovation Challenge Award

Recipients of the 2022 President’s Innovation Challenge (PIC) Award were announced in a ceremony in early May. The event brought together an audience of over 2,000 viewers from 64 countries. The PIC program funds Harvard student, alumni, and affiliate innovations through funding from the Bertarelli Foundation . Throughout the seven-month process, teams developed their ventures with robust support from the Harvard Innovation Labs . This year’s winners include Christina Glover (MDes ’19) and Alex Berkowitz (MLA I ’23).

Christina Glover and Kristin Nuckols, a collaborator from the School of Engineering and Applied Studies , created a robot-assisted virtual clinic that restores hand function to stroke survivors. They describe Imago Rehab as “transforming the post-stroke standard of care by bringing evidence-based, high-intensity rehabilitation into the home. Their robot-assisted virtual clinic enables superior hand recovery for the five million stroke survivors in the U.S. with lasting hand impairment. Telerehab eliminates travel burdens to allow greater access to care, while a wearable robotic glove facilitates daily, high-repetition hand rehab from the comfort of home. This digital health solution results in better outcomes and increased independence as chronic stroke survivors are able to use their hand again for the first time since their stroke.”

Alex Berkowitz’s project, “Coastal Protection Solutions ,” is an initiative to mitigate coastal flooding through two systems. The first, “The Wavebreaker,” works as a wave speed bump, decreasing wave velocity to the shore and reducing damage to residential and commercial property. The second is an artificial floating marsh system that builds the coastline up and outward to protect the shoreline from the threat of sea-level rise and storm surge.

Alfredo Thiermann contributes to the Chilean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

Turba Tol Hol-Hol Tol , a collective project on display as part of the 59th Venice Biennale , features an interdisciplinary team of Chilean creatives, including Alfredo Thiermann, design critic in Architecture at the Graduate School of Design (GSD). The pavilion is a multisensory sound and video installation that exhibits the cultural, political, and environmental relevance of the peatlands in Patagonia and their relationship with their original inhabitants, the Selk’nam people. Turba Tol Hol-Hol aims to provide an experimental path toward conserving the peatlands through research, education, and collaborations with the Wildlife Conservation Society–Chile, Karukinka Park in Tierra del Fuego, and the Selk’nam Hach Saye Cultural Foundation.

The Chilean Pavilion is curated by Camila Marambio, an independent US-Chilean curator who founded Turba Tol Hol-Hol Tol as a research project and collective “emerging out of eco-relational philosophy and post-humanist cultural theory, particularly related to the ethics of living and dying in a time of ecological crisis.” “Hol-Hol Tol” means the “heart of peatlands” in the language of the Selk’nam people, who are Indigenous to Tierra del Fuego, Patagonia. The peat fields in this region are part of a delicate natural environment and are drying up under the threat of climate change, mining, peat moss harvesting, and ecological degradation. Once drained and destroyed, peatlands go from being carbon sinks to being sources of carbon emissions, releasing enormous amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The Selk’nam believe that their first ancestors became mountains, rivers, trees, and animals, and every element of nature is sacred. They insist that peatlands are a living body and a reservoir of memories, “We are claiming a society of mutual care: peatlands and bog people are indivisible.” Members of the Selk’nam people are also involved in the project.

“Our project is invested in a tour de force for visibility, visibility of a landscape and ecosystem that is in danger, and visibility of a people that has been violently deprived of their most fundamental condition of existence: namely, the fact of being recognized as such, as a living and existing culture,” says Thiermann. “Invested with such aim for visibility, Venice has a clear relevance for this project, because it can bring those issues to the fore, and in so doing it can influence, we hope quite directly, the political ethos of both entities that we are concerned with: the Selk’nam people and the peatlands, not only from Chile but across the globe.”

Dominga Sotomayor, visiting lecturer at Harvard’s Department of Art, Film, and Visual Studies, is also part of the Turba Tol Hol-Hol collective and contributed to the installation. Additional members of the project include Ariel Bustamante, an artist whose work focuses on transhuman conversations and Andean listening practices, and Carla Macchiavello, an art historian and educator whose research focuses on contemporary Latin American artistic practices linked to ecology and social change. The artists are joined by ecologist Bárbara Saavedra, Selk’nam writer Hema’ny Molina, and cultural producer Juan Pablo Vergara, among others.

Thiermann is an architect and founding partner of Thiermann Cruz. Through his design practice and theoretical research, he explores the intersection between architecture and different media, from sound installations and film scenography to single-family houses, public buildings, and large-scale infrastructures. He has taught and lectured at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and other institutions. Thiermann’s written and built work has been published in Revista ARQ, TRACE magazine, Zeppelin, Potlatch, Real Review, Thresholds, Archithese, GTA Papers, and BauNetz, and has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Santiago, the Istanbul Design Biennial, Museo MAC Quinta Normal, and Centro Cultural Estación Mapocho, among other institutions.

Environmental Justice, Energy Infrastructure, Migration and War: What Role Does Design Play in Mitigating a Crisis?

At their speculative edge, the design professions flourish in envisioning future scenarios, and we usually imagine these to be positive additions to a well-ordered world. A true crisis throws fundamental assumptions into disarray, requiring designers to rethink the way they operate as the ground shifts beneath their feet. The old rules of geopolitics suddenly don’t lead the imagination anywhere predictable. What’s left is a feeling that the game itself is being reinvented.

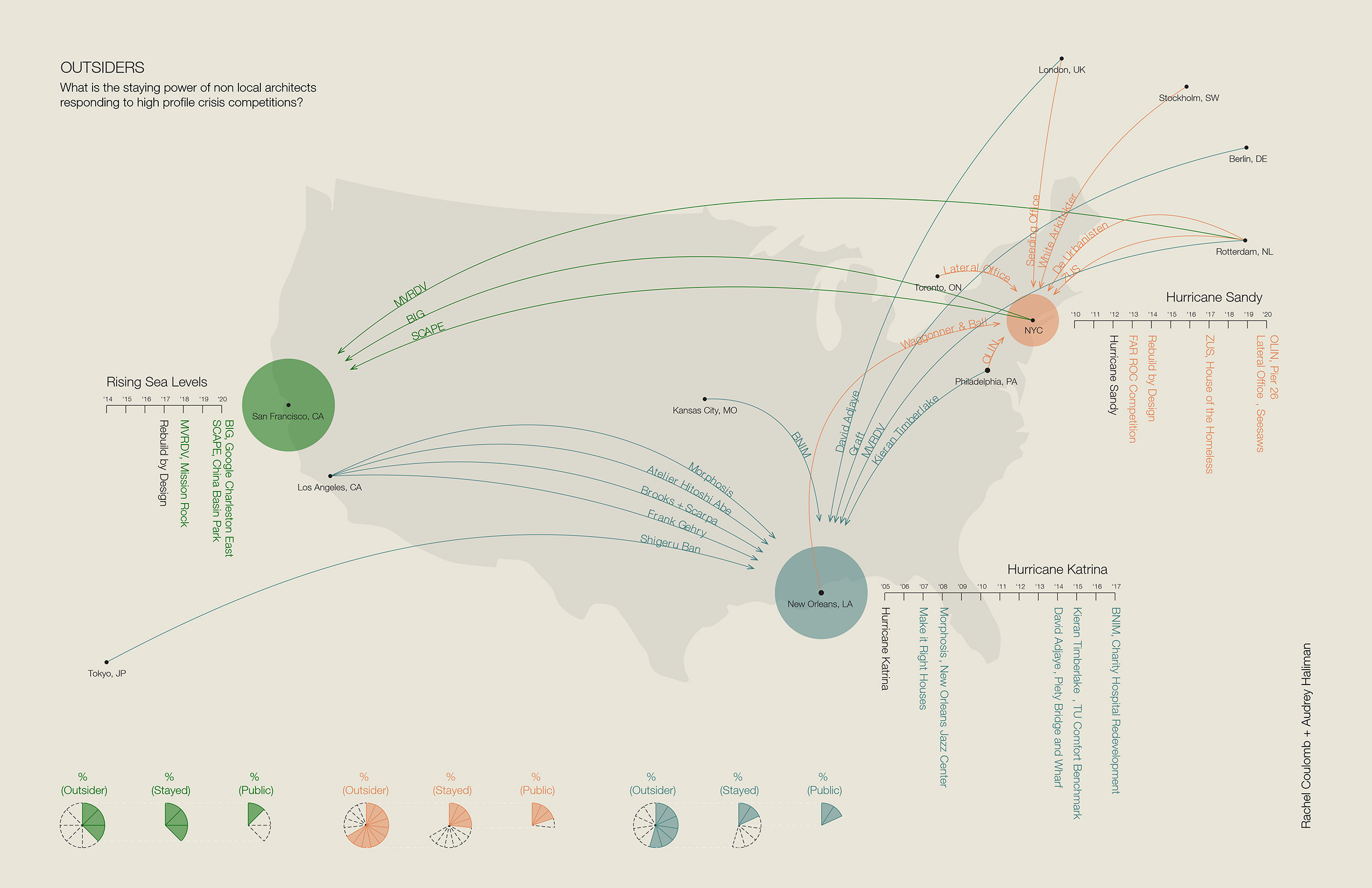

In the past two years, the theme of crisis has been studied across the GSD at the annual Practice Plenary, and lessons learned by investigating responses to pandemics and hurricanes can help us look at responses to crises happening now across the globe. I spoke with three professors teaching practice courses and plotting new modes of practice in architecture and urban planning. All three encouraged humility, and they spoke of the central place for self-reflection in designing a profession better able to address injustices and inequalities. Asked about the ongoing war in Ukraine, Elizabeth Christoforetti, a founding principal at Supernormal and an assistant professor in practice of architecture, urged caution: “It’s a response time question. We’re just not built to respond quickly as a profession. It can feel frustrating, not being able to confront the crisis, but our impact happens in different ways.” Jacob Reidel, also an assistant professor in practice of architecture and a senior director at Saltmine, a technology startup, suggested that designers “focus on what our responsibility is as engaged citizens,” noting that “there’s a tendency to try to make everything a design problem—but there are other ways one can and should be active in the world.” Matthijs Bouw, founder of One Architecture and Urbanism, saw a parallel between his work on climate adaptation and the exodus from Ukraine (there are more than 5 million refugees so far): “One of the things I worry about is how our cultural fabric will be able to cope with the climate crisis and the associated migration. It’s going to change our cities in drastic ways.” The war also exposes problems with the global energy infrastructure: “We should have been investing much more in renewables and decentralized systems,” Bouw says. “This is an issue of environmental justice. Who gets to own the energy infrastructure? Many communities have really suffered in the past from energy infrastructures.”

Bouw’s work and teaching at the GSD has placed designers at the edge of several unfolding crises. Among his best-known projects at One Architecture and Urbanism is the Big U—a proposal for a protective system that encircles Manhattan to mitigate the effects of rising sea level—which was originally developed with a multidisciplinary team including BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group). The associated research and design continues in ONE’s work on the Financial District and Seaport Climate Resilience Master Plan, among other projects. This semester at the GSD, Bouw is teaching “Houston: Extreme Weather, Environmental Justice, and the Energy Transition.” The course begins with the premise that crises have a tendency to build on one another. Bouw says it’s important to distinguish between two types of crisis: “There are slow-running crises that are eating away at people’s health and livelihoods, or coastal areas, or ecosystems, and then there are catastrophic crises that are—in the language of resilience—low probability and high impact.”

As Bouw explains, “During COVID, we have seen how public health is related more than ever to issues of structural racism, to our fossil fuel economy (because of pollution and respiratory issues), and so on.” This logic applies to other crises as well: “The climate crisis is intimately connected to the biodiversity crisis.” The complexity inherent to interrelated systems is the first problem found in crisis situations, he says. “There is a lot that we don’t know about these relationships, but we do know that many of these relationships play out on a systemic scale and bring with them a high level of uncertainty.”

Bouw advises that we should approach crisis through careful research and as part of a team. “Projects you do as a practitioner cannot stand on their own,” he says. “Any project is part of something much bigger.” This can be an uncomfortable situation for designers: “I was trained as a designer to stand in front of an audience and say, ‘This is the big idea,’ and then try to sell the idea,” Bouw says. “That’s an ethic of the past. You need to start thinking about yourself more as a participant in a much more complex process.” Design in face of crisis requires “the right mix of willfulness and humility.”

This doesn’t mean abandoning the tried-and-true techniques of design. Bouw emphasizes the importance of “tools for communication—creating the material to make conversations easier—and the tools of research through design exploration.” He says that design professionals play an important role as mediators: “Balancing the systemic dimension with the hyperlocal or the hyperprecise is what we do.” This is particularly important in large-scale crises, which are also largely invisible. Take the climate crisis, for example. “Given the magnitude of changes that we need to make in our Earth system,” Bouw says, “we need to develop quick ways of learning and protocols that can be scaled and replicated, and which don’t get in the way of the nuance that’s needed in some situations.” He cautions that there is no single framework for understanding something so complex. “The Earth system as a whole cannot be captured in an algorithm,” he observes. “You need to understand the limits of the algorithms you develop because otherwise you start to reduce reality to the algorithms.”

Asked about specific participatory design practices, Bouw notes that they vary around the world: “In planning in the Netherlands, we are employing design in a more integrated way to engage complex processes. Planning in the United States is relatively disassociated from design—the tools of planning are predominately things like texts and spreadsheets and PowerPoints. It doesn’t tend to test things and try to see how things come together on the ground.” For Bouw, this tendency avoids the crucial questions of practical engagement: “What would it take to implement this? Where could it get funding from? How do we engage the powers that be in the set processes of delivering projects?” Without practical, on-the-ground participation, Bouw says, “the end is often either paralysis or business as usual, and we can’t do either.”

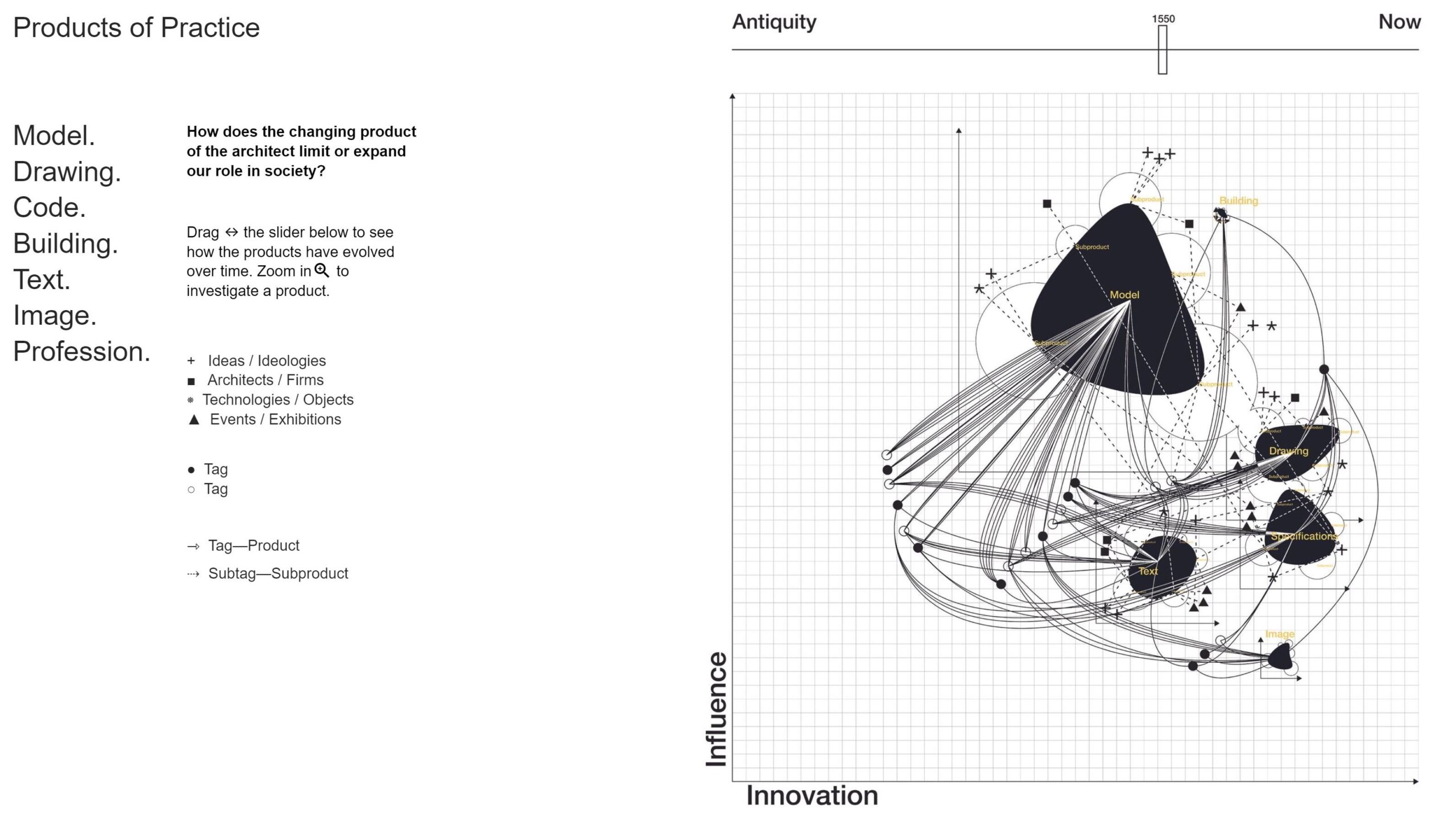

Crisis frequently spurs invention. In her class this semester, Elizabeth Christoforetti focuses a historical lens on a range of design practices to ask when and why they were first formulated. “Products of Practice” begins by showing students that “the profession of architecture is actually relatively new,” she says. “It came out of a number of radical social and economic changes—the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution, for instance.” The course builds on Christoforetti’s class last semester, “Elements of the Urban Stack,” which delaminated the built environment from its most expansive social fabric to its smallest detail. Across both classes, Christoforetti asks students to “look back at historical hinge points to see, for instance, how architectural specifications changed over time and how those changes impact the architect’s agency or relationship with society.”

This approach gives students a perspective on the possibilities of design practice. “The best thing we can do is to understand the limits of the structural framework of practice now,” Christoforetti says, “and where we can or must push boundaries if we want to change things.” Critical reflection plays an important role in formulating new directions. “We can identify what the value systems out there are—in the discipline, in practice, and in society at large,” she says. “Then if architects want to impact the future of housing, for example, maybe the thing to do isn’t to design a single-family home. Maybe it would be better to go work for Fannie Mae and design mortgages, because they shape housing at scale. Or maybe it’s okay to just design a really remarkable single-family home. But it’s a choice about impact and agency.”

This wider view of practice suggests an expanded notion of professional ethics. Christoforetti asks, “Do we need a redefinition of design in an era when we are accountable to the major crises of the moment, whether it’s climate change, war, systemic racism, or computer surveillance? Is form enough?” This can appear sometimes as a drastic decision to be made—a fork in the road. “Maybe we’re thinking about how to fundamentally redefine our practice, and maybe the profession as we know it dies as a result,” Christoforetti speculates. This sort of wholesale redefinition has happened before, and like previous hinge points, she says, “We live today in an unprecedented moment for the role and agency of the designer.”

When it comes to dealing with the compounding crises of the contemporary world, Christoforetti is particularly interested in the problems and potentials of computation. She cites Architectural Intelligence by Molly Wright Steenson which mentions that, in the world of technology, the verb “to architect” refers to the design of information systems. “The people she writes about are not thinking about buildings per se,” Christoforetti says, “they’re thinking about something much bigger. They’re thinking about an operative process for creation.” She pinpoints the central conundrum of contemporary professional practice in a way that parallels Bouw’s observations: “The crisis that we look at in “Products of Practice” is one of scalable systems and late capitalism.”

The professional practice course taught by Jacob Reidel last semester also took a historical perspective. He notes that “the profession of architecture as we currently understand it is not nearly as old or straightforward as is often assumed.” On this basis of historical contingency, “Frameworks of Practice” is designed to get students “to look critically at what they’ve been told it means to be an architect, and to see both the profession and their own careers as designed things,” Reidel says. Opportunities provided by unexpected circumstances offer a good starting point for this investigation. “Crises, even if only temporarily, tend to throw the old way of doing things out the window,” says Reidel, and he has numerous examples.

“One of the few built responses to the crisis of COVID,” he points out, was the “thousands of structures built in the street, practically overnight, in one of the most heavily regulated built environments in the world, New York City. All the rules had to be rewritten, and myriad public and private entities had to come together to figure out how to make it possible for the restaurant industry to continue operating. Suddenly the Department of Transportation was regulating building because the shacks were in the street.” The result was the Open Restaurants and Open Streets programs, the latter of which set itself the task of “transforming streets into public space open to all,” according to their website. This made for an apt case study in the relationship between crisis and design—and it became the subject of the second Practice Plenary.

Reidel brings the questions raised by Open Restaurants and Open Streets to bear on a wider investigation of design. “What did it reveal about how the design professions can and cannot effectively engage in moments of crisis?” he asks. One lesson involves seizing opportunity. Reidel tells the story of the creation of the re-ply program: “During the first COVID summer of 2020, many businesses in New York City temporarily covered their storefronts in plywood. Seeing that a ton of valuable plywood was headed to the dump, members of the small New York studio of the international Australian practice BVN began collecting plywood from businesses and landlords, some as big as Rockefeller Center’s Tishman Speyer, and started a pro bono effort to repurpose it into affordable outdoor seating for local restaurants that couldn’t serve food indoors because of COVID. What started as plywood furniture eventually became a kit-of-parts streetery building system named re-ply that’s now operating almost like a small independent product business within the larger BVN design practice.” It’s an example, Reidel says, of how a crisis can spur “new approaches to operating as an architect.” The example suggests the importance not only of having a good eye for opportunity, but also of being prepared. This is the practical, on-the-ground knowledge that Bouw also emphasized.

Although the place of design may be far from the battlefield, it can help to think about crisis situations in terms of wartime mobilization. “What we are trying to do as a practice is to have the boots on the ground and to change the practices of implementation,” Bouw says. “It is difficult to build coastal adaptation projects or integrated stormwater projects that also improve the urban environment as a whole and deal with other systemic issues. We have to create the conditions necessary to capitalize on those opportunities.” A lot of the work involved in addressing crises comes beforehand, in the form of research and planning—and this requires being out there, on the ground, embedded in the complex systems in which we may have to intervene. So whether it’s destabilized ecosystems, new technologies, or something else driving change, Bouw’s advice applies: “A shock is also often an opportunity, but we need to have equitable plans ready before the event occurs.”

Lara Avram and Daniel Haidermota awarded 2022 KPF Travel Fellowship

Each year, the Kohn Pedersen Fox Foundation (KPF) sponsors a series of fellowships to support emerging designers and advance international research. KPF recently announced Lara Avram (MArch AP ’23) and Daniel Haidermota (MArch ’23) received the 2022 Kohn Pedersen Fox Traveling Fellowship , established to broaden the education of a design student in their last year of school through a summer of travel and exploration. The Traveling Fellowship is given to students from one of the 27 design schools with which KPF has partnered to fund summer research on “far-reaching topics that push the boundaries of critical thinking and architectural design.”

The jury was comprised of chair Julia Backhaus, Assistant Professor of Architecture and Director of Enterprise at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London; Mike Tonkin, Director and Founder of Tonkin Liu, Architect, Landscape Designer and Teaching Fellow at Bath University and External Examiner at the Bartlett; Anupama Kundoo, Director, Anupama Kundoo Architects; Brian Girard, Design Principal at KPF, and James von Klemperer, President of KPF.

While the Fellowship is administered and awarded by KPF, the foundation requires that participating institutions nominate their students. There is an internal departmental selection process which occurs prior to final submission of materials to KPF and information about this process is communicated to students each year by the GSD Architecture Department. Learn more about the Fellowship through the Fellowships, Prizes, & Travel Programs webpage.

Harvard Design Press announces fall 2022 titles

Following the launch of Harvard Design Press last spring, the Press is pleased to announce the release of three titles this fall: John Andrews: Architect of Uncommon Sense, Frida Escobedo: Split Subject, and Empty Plinths: Monuments, Memorials, and Public Sculpture in Mexico.

Documenting John Andrews’ path from Australia to the United States and Canada and back again, John Andrews: Architect of Uncommon Sense by Paul Walker, examines his most important buildings and reveals how the internationalization of architecture during this period was an unexpectedly dispersed geographical phenomenon, following more complex flows and localized progressions than earlier modernist ideas that travelled from center to periphery, metropole to outpost. Andrews negotiated the advent of postmodernism not by ignoring it, but by cultivating approaches that this new era foregrounded—identity, history, place—within the formal vocabularies of modernism. As Andrews assumed wider public roles and took appointments that allowed him to shape architectural education, he influenced design culture beyond his own personal portfolio. This book presents Andrews’ legacy traversing local and international scenes and exemplifying late-modern developments of architecture while offering both generational continuities and discontinuities with what came after. John Andrews: Architect of Uncommon Sense features essays from Paul Walker, Mary Lou Lobsinger, Peter Scriver and Antony Moulis, Philip Goad, and Paolo Scrivano, along with nearly 100 new photographs of existing buildings designed by Andrews in North America and Australia from visual artist Noritaka Minami.

Split Subject, an early project by architect Frida Escobedo, deconstructs a fraught allegory of national identity and architectural modernism in Mexico. Unpacking this project and tracing its enduring influence throughout Escobedo’s career, Frida Escobedo: Split Subject reveals a multi-scalar and multi-medium practice whose creative output encompasses permanent buildings, temporary installations, public sculpture, art objects, publications, and exhibitions, and bares at its center a sensitivity to time and weathering, material and pattern, and memory. It includes essays by Julieta Gonzalez, Alejandro Hernández, Erika Naginski, Doris Sommer and José Falconi, and Irene Sunwoo, and a foreword by Wonne Ickx.

Empty Plinths: Monuments, Memorials, and Public Sculpture in Mexico responds to the unfolding political debate around one of the most contentious public monuments in North America, Mexico City’s monument of Christopher Columbus on Avenida Paseo de la Reforma. In convening a diverse collective of voices around the question of the monument’s future, editors José Esparza Chong Cuy and Guillermo Ruiz de Teresa probe the unstable narratives behind a selection of monuments, memorials, and public sculptures in Mexico City, and propose a new charter that informs future public art commissions in Mexico and beyond. At a moment when many such structures have become highly visible sites of protest throughout the world, this new compilation of essays, interviews, artistic contributions, and public policy proposals reveals and reframes the histories embedded within contested public spaces in Mexico.

A book-publishing imprint based at Harvard GSD and distributed in collaboration with Harvard University Press, Harvard Design Press challenges, broadens, and advances the design disciplines and advocates for the value and power of design in making a more resilient, just, and beautiful world. In pursuit of new, original ideas on the research and practice of architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning, and urban design, the Press seeks book proposals from researchers, practitioners, theorists, historians, and critics, among others. More information about submitting a proposal can be found on the Harvard Design Press’s webpage.

Harvard Design Press is organized and edited by Harvard GSD’s Ken Stewart and Marielle Suba, and guided by an Editorial Board composed of Harvard GSD and Harvard University faculty. Alongside Dean Sarah Whiting, the Harvard Design Press Editorial Board includes Harvard GSD’s Martin Bechthold, Anita Berrizbeitia, Eve Blau, Ed Eigen, K. Michael Hays, Niall Kirkwood, Mark Lee, John May, Rahul Mehrotra, Erika Naginski, Jacob Reidel, and Sara Zewde, as well as Harvard University’s Lizabeth Cohen, Sarah Lewis, and Patricio del Real.

To learn more about Harvard Design Press and explore submission guidelines, please visit the Harvard Design Press’s webpage. To stay up-to-date on new releases and general Harvard GSD news, please visit Harvard GSD’s homepage and subscribe to its Design News updates.

Harvard GSD announces three new faculty appointments

The Harvard Graduate School of Design is happy to announce the appointments of Jonathan Grinham as Assistant Professor of Architecture, Ana Maria León Crespo as Associate Professor of Architecture, and Hannah Teicher as Assistant Professor of Urban Planning, effective July 1, 2022.

Jonathan Grinham has served as Lecturer in Architecture at the GSD and a Senior Research Associate with the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities since 2018. He holds degrees in architecture and building science from Virginia Tech and a D.Des. degree from the GSD. Jonathan’s research brings an intensely interdisciplinary approach to climate change and the built environment, connecting material science with building science and design to examine questions on materiality, thermal health, and lifecycle carbon emissions. These questions have sparked the development of novel technologies, publications, and patents that address low-carbon building solutions through material innovation. Jonathan’s research has gained significant recognition through numerous funding awards, including the Harvard Climate Change Solutions Fund, the prestigious Department of Energy Advanced Building and Construction program, and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering’s Validation Project program. Jonathan is passionate about translating his research into design-based learning. His teaching on the science of materials in the face of climate change continues to push the boundaries of building materials.

Ana María León Crespo joins us from the University of Michigan, where she was Assistant Professor in the History of Art and Romance Languages and Literatures departments, and in the School of Architecture. Ana María’s work studies how spatial practices and transnational networks of power and resistance shape the modernity and coloniality of the Americas. Ana María holds a diploma in architecture from UCSG Ecuador, an M.Arch. from Georgia Tech, an M.Des. with distinction from the GSD, and a Ph.D. in the History, Theory, and Criticism of Architecture from MIT. She serves on the boards of the Global Architectural History Teaching Collaborative (GAHTC) and the Society of Architectural Historians and is co-founder of several collectives laboring to broaden the reach of architectural history, including Nuestro Norte es el Sur (Our North in the South), a group of architectural historians working from and about Latin America, and the Settler Colonial City Project, a research collective focused on the collaborative production of knowledge about cities on Turtle Island/Abya Yala/The Americas as spaces of ongoing settler colonialism, Indigenous survivance, and struggles for decolonization.

Hannah Teicher, currently a Researcher-in-Residence at the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions, University of Victoria in Canada, joins the Department of Urban Planning and Design as an expert in mitigation and adaptation to climate change. Her research focuses on novel collaborations that advance adaptation, embodied carbon at the urban scale, and climate migration with a focus on receiving communities. For the Climigration Network, dedicated to closing the gap between communities and practitioners on assisted relocation, Hannah serves on the Network Council and Co-Chairs the Narrative Building Work Group. Hannah has a Ph.D. in urban and regional planning from MIT, an M.Arch. from the University of British Columbia, and a B.A. in Sociology and Anthropology from Swarthmore College. She received the Martin Fellowship for Sustainability in support of her research on urban/military collaborations for adaptation. Before beginning her doctoral studies in 2014, Teicher practiced architecture at Shape Architecture in Vancouver, served as a researcher for the Transportation Infrastructure and Public Space Lab, University of British Columbia, and taught at Emily Carr University of Art and Design. In 2014, a green infill project she worked on with Shape Architecture won the Vancouver Urban Design Award for Outstanding Sustainable Design from the City ofVancouver, and in 2013 an EV charging project she collaborated on with the TIPS Lab received the American Institute of Graphics Arts (Re)design Award.

Designing Sustainable Solutions for a Better Built Environment: A Meeting of Ideas at Harvard’s Center for Green Buildings and Cities

Commemorating Earth Day, the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities (CGBC) hosted its first in-person event since the beginning of the pandemic, featuring six short presentations by GSD faculty whose research relates to designing sustainable solutions for a better built environment. The topics of the presentations ranged from algae-based biomaterials to urban infrastructure, and were followed by five-minute Q&A sessions. All work was supported by CGBC faculty grant awards.

The timeliness of addressing these environmental challenges was highlighted by James Stock , Harvard’s new vice-provost for climate and sustainability, who stressed the importance of interdisciplinary communication in his keynote address, pointing out the scale of the problem in monetary terms: “Our energy system, from what we are doing, is imposing $600 billion in damages, every year, on future generations.” He also warned of the dangers of merely “spending money to feel good without actually solving the problem.”

The six speakers all presented their research aimed at improving the built environment with one clear vision in mind: “to transform the building industry by developing new processes, systems, and products that lead to more sustainable and high-performance buildings and cities,” according to the opening address from Ali Malkawi, founding director of CGBC , director of the Doctor of Design Studies Program, and professor of architectural technology.

Algae-Based Biomaterials for the Built Environment

Martin Bechthold, Kumagai Professor of Architectural Technology, presented a unique solution to the challenge of reducing the embodied carbon footprint of the construction industry. By developing new algae-based materials that absorb CO2 during photosynthesis, Bechthold proposes that the built environment could be transformed into a carbon storage device on a large scale, sequestering carbon in the material itself and holding it for the lifetime of the building.

Working in collaboration with a team of material scientists at Caltech led by Professor Chiara Daraio , the GSD’s researchers have been focused on the practical challenges and implications of the algae-based material being developed at Caltech: How can we fabricate functional building components from it, while navigating its active properties? What opportunities and efficiencies might it offer us? Bechthold noted that a growing network of colleagues and partners has been fundamental to their research, thanks to the CGBC.

Reshaping Urban Environments through Infrastructure Design Protocols (Phase I + II)

Rosalea Monacella, design critic in landscape architecture, offered timely insight into the increasing demands faced by the electrical power grid—and how design can provide solutions while simultaneously addressing the global implications of climate change. As urban communities grow and put pressure on existing infrastructures, a radical reevaluation is required in order to develop adaptable, modulating structures for the future. This means understanding and anticipating not only environmental concerns but also the technological, economic, logistic, and social challenges for the cities of tomorrow.

Tellingly, she noted how sorely out of date America’s national grid infrastructure is: “The majority of the transition and distribution lines were constructed in the 1950s and ’60s, with a life expectancy of 50 years.”

The team’s design research was intended to develop deployable prototypes that work on a regional scale, giving individual cities control, responsibility, and accountability for their own power and water consumption, drawing resources from their local environs.

Energies of the Night: Nocturnal Public Space and Energy Policy in the Arabian Peninsula

Considering the geo-social implications of design in the Arabian Peninsula, Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture Gareth Doherty gave a presentation centered around the use of public spaces after-hours. Given that communities in this region tend to socialize when darkness falls and the temperature drops, there is a need to come up with less light-polluting solutions.

Drawing on field research conducted through his “Design Anthropology” seminar, Doherty explored the possibilities of more efficient design for darkness, plus strategies to make better use of cooler temperatures and remediating lighting needs. “Navigating the dark spaces of the night calls for the activation of our senses, beyond the primacy of the visual,” he says.

Benefits of Building-Level Heat Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies

It is a self-perpetuating problem that the issue of urban heat is exacerbated by building design. Consequently, as Associate Professor of Architecture Holly Samuelson explained, the onus is on architects, urban planners, and designers to come up with strategies for heat mitigation—noting that, “In 50 years, there could be billions of people that are susceptible to temperatures and climates that are outside of the conditions that have served humanity well for the past 6,000 years.”

As Samuelson pointed out, this can also have implications for the health of the urban community thanks to factors such as heat exposure and greenhouse gas emissions. In addressing such a multifaceted problem, a joined-up approach is required—one that considers the impact of building design strategies at different scales, while demonstrating a reproducible and scalable framework that can inform future work.

Evaluating Location-Based Sustainability at the Site Level

Carole Turley Voulgaris, assistant professor of urban planning, highlighted the need for greater consistency in the methodology for measuring vehicle miles traveled (VMT) at site level for existing and proposed developments. She explained that it’s “one way to measure the sustainability of a particular location.” Research was undertaken into existing office sites in both the San Francisco Bay Area and the Wasatch Front Region of Utah.

With VMT estimations varying considerably, it was noted that discrepancies are often magnified as the figure is multiplied to cover wider areas. The team suggested that further research is required to prioritize the “four Cs”: consistency, cost-effectiveness, closeness, and conservatism.

The Oasis Effect: Agricultural Practices in Arid Environments

With a backdrop of climate change and aggravated environmental degradation, the challenges of agricultural practices in extreme arid environments are only going to become more severe. With this in mind, Pablo Pérez-Ramos, assistant professor of landscape architecture, explained how his team’s research had produced a typological matrix of oases, allowing for a methodological and comparative study of them. It’s a resource that will become increasingly relevant as the effects of global warming and the resultant shifts in landscapes intensifies.

Pérez-Ramos announced that his team will soon be able to conduct field research that includes the use of drone technology to measure the thermal shock induced by the presence of vegetation and water.

Ali Malkawi concluded the meeting by saying, “It’s been wonderful to see this impactful research grow as a result of the CGBC seed funding—and continue to gain traction.” He also announced the issuing of at least five new awards for the coming year.