Meriem Chabani Designs Sacred Spaces within the Profane

Several years ago, Meriem Chabani, Aga Khan Design Critic in Architecture at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), spent countless hours learning to hand-tuft wool rugs in the Berber tradition for which her homeland, Algeria, is globally renowned. The result, Mediterranean Queendoms, was exhibited in the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale . A richly textured triptych in earthen hues, blues, yellows, and grays, the carpet tells the story of Chabani’s mother’s and two grandmothers’ homes in iconographic imagery that evokes animals, Berber patterns, and cityscapes, to chronicle her family’s diasporic journey and ability to bring home with them.

“In many different cultures, including my own,” explained Chabani, “textiles have historically been a way of meaning-making, of carrying stories and transmitting knowledge. I explored how we could use one form of textile crafts—carpets—to provide full representation for housing.”

As an Algerian who grew up in France and experienced the long-lasting effects of colonization and war, Chabani knows how it feels to “exist in the periphery,” even as she “deconstructed its existence.” She turns to the language of feminist theorist bell hooks to “put the margin at the center,” and grounds her designs in “spiritual and sacred practices with the built environment,” centering care and “acts of faith” that help us to more productively share space together.

The rug serves as a symbol of how women hold familial and cultural information in the diaspora, carrying it with them just as they roll up and transport the carpet “from one home to another, across the sea,” writes Chabani on her website. It is unrolled again in a new home where women “care for, maintain and transmit resources, values, presents, medical care, family objects, furniture.”

This fall, Chabani spoke at the GSD about the place the carpet holds in her practice and how her firm, New South, co-founded with John Edom, creates spaces for diasporic communities from the Global South and foregrounds their architectural heritage within the North. Citing theorist and writer Paul B. Preciado, she argued in her talk, “South South Cosmogonies,” that the South is a fiction created in contrast to the North, “shaped by subjugation and uneven power relations.”

“The South is the site of extraction,” she explained, “the North is the site of value-making. The South is the site of magic, feminine, queerness, gold, and coffee; the North is the site of science, masculinity, coordination.”

Her firm’s recent projects include a religious and cultural center in Paris and the Muqarnas Pavilion, the latter of which was inspired by the muqarnas used for centuries in Islamic architecture. “Muqarnas are a decorative molding,” Chabani explained in her talk at the GSD, “applied to ceiling vaults . . . across Islamic culture. At first glance, they appear to be intricate decorative ornamentation, but they also serve a practical purpose.”

She went on to explain that they may have evolved as a result of the shapes made when a brick structure transitions from an octagonal floor and walls to a domed ceiling, and that they reflect the Islamic “non-figurative approach to ornamentation.” The shape continued to evolve and is now made from plaster. She decided to use it in her design because it would allow her to explore a sacred space installed in a profane setting, and to “reassert constructive and construction innovation as central to contemporary Islamic architecture.”

An outdoor installation that Chabani designed in collaboration with Radhi Ben Hadid, a structural engineer, and Gorbon Ceramics, the pavilion is made of many half-cupolas molded in industrial grade, vibrant blue ceramic. Muqarnas are typically installed in a dome or arch as a decorative element, but Chabani’s goal was to create a self-supporting half-dome of muqarnas. She found that, because ceramics change in the firing process, the molds could not be 3D-printed and were instead hand-crafted.

The installation is what she calls in French a courage perdue, or lost risk, as it required reinforcement with concrete that’s then covered with soil and planted with greenery. Installed in the grass with trees behind it at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Saint-Étienne, in France, the pavilion looks like a bright blue shelter hidden within nature. Visitors can walk into the curved space that’s been used for performances and presentations; Chabani noted that it’s also enticing for curious children.

Another design that combines secular and religious spaces, the mosque and cultural center she has designed for the 11th arrondissement in Paris would replace the current mosque that the community uses, in a renovated paper factory. Chabani cited the building’s dilapidated facilities and insufficient space for the number of people who want to worship as some of the primary drivers for a new mosque. But, these issues are part of a systemic problem, she noted, explaining that Paris currently meets only about seven percent of the population’s needs for mosques, and that France is systematically eliminating worship spaces in immigrant communities. Government-run housing units for immigrants are currently being renovated, and the new spaces for worship are too small for communities to use together.

When the Muslim community in the 11th arrondissement asked Chabani to help them design a mosque, she thought about contemporary attempts to modernize mosques that only create caricatures without capturing their essence. So, she began with a fundamental question: What is a mosque? She determined that it must be “oriented toward Mecca, provide a clear distinction between sacred and profane spaces, and allow people to pray collectively.” Because the lot is just over 900,000 square feet, Chabani and her team deployed the vertical space, using a Chambord stair system to allow people to filter into the upper levels of the mosque without waiting until lower levels are full, eliminating the issue of overflow into the street as people wait in line to pray.

She went on to consider what might happen if the traditional architectural elements of a mosque—the minaret, dome, and pointed arches—were not prioritized. Instead, she found her way with the words, aya tonerre, which translates to “God is light upon light.” Her design prioritizes the movement in the space, as people pray five times a day, and challenges the idea of erasure of the community with chain-metal cladding—a nod to the metal working history of the neighborhood—that can be opened or closed around the “glass house.” Within the building, multifunctional rooms, including a library, exhibition space, and offices can be divided with floor-to-ceiling sheer curtains, adaptable for various sacred and secular purposes.

In her architecture studio course this semester at the GSD, “Anchoring Acts,” she continues to explore relationships between sacred and secular spaces. She led students through a study of New Orleans, urging them to consider “not only greener technologies” in the service of environmentalism and sustainability, but also “the affective and sacred dimensions of care.” An anchoring act, she explained, is a “ritual or relationship based on spiritual or sacred practice with the built environment.”

Similarly, Chabani sees an opportunity to learn from the traditions and rituals of the many diasporic communities in New Orleans—African, Caribbean, Indigenous, Arab, Spanish, French, Creole, Cajun, Pacific, and Vietnamese—elucidating how “place, memory, and belief shape the built environment.” She calls their overlapping cultures “entangled cosmologies.” To learn more about those intersecting communities and their influence on American culture, during the studio course’s trip to New Orleans, students visited iconic Congo Square, known as the musical center of the city.

It was there that, as Freddi Evans, author of Congo Square: African Roots in New Orleans , explained in a lecture to Chabani’s class, enslaved Africans who were taken from different regions of their home continent—Bight of Benin, Central Africa, Sierra Leone, and Senegal—would intermingle on Sundays, sharing instruments, songs, drumming, and other traditions from their homelands, leading to the creation of a range of musical instruments, dances, voodoo and other spiritual practices, and, of course, jazz.

Together, the group also attended a Second Line, a ceremonial parade with music through the Tremé neighborhood, and took a tour of “Geographies of Displacement” with 2025 Loeb Fellow Shana M. griffin. griffin’s multimodal series DISPLACED “traces [New Orleans] geographies of Black displacement, dislocation, confinement, and disposability in land-use planning, housing policy, and urban development . . . highlighting moments of refusal, rupture, and protest.” She encouraged the students to “reimagine space-making and abolition strategies that value Black life.”

For examples of this kind of abolitionist work in the built environment, the group met with a variety of organizations focused on underserved communities in the city, including Tulane’s Albert Jr. and Tina Small Center for Collaborative Design, directed by 2013 Loeb Fellow Ann Yoachim .

As students worked towards their final projects for the course, Chabani described the wide range of themes they explored, from “fire rituals and carbon capture, probing the tensions between sacrifice, material performance, and durability” to “rituals of rebuilding, where architecture becomes a medium for repair, knowledge transfer, and resilience in the face of climate catastrophe.” One student, for example, mapped people’s movement around Congo Square to design a gathering space that also functions as a parking garage and will eliminate the need for nearby parking lots, while another applied lessons from bamboo scaffolding experts in Hong Kong to create a building at the local technical school that can serve as a model and learning space for hybrid bamboo-and-wood buildings.

Moving ahead, Chabani continues to probe the connections between sacred and secular spaces, re-centering the Global South, and exploring how these threads can lead us to better care for our environments and each other.

From Albemarle to Allston Yards: Ellie Sheild Bridges Planning and Real Estate

Ellie Sheild (MUP ’23, MRE ’24) didn’t set out to become a planner, much less a real estate developer. As an undergraduate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, she majored in political science and Spanish with a women’s studies minor, scanning the course catalog for a summer class that didn’t meet on Fridays. The one she chose—an introduction to city and regional planning—quietly rearranged her life.

“That class was the first time I really understood the systems that shape everyday life,” she recalls. What began as a scheduling convenience became a new way of seeing the world: zoning codes and transportation plans as levers that determine where people live, work, shop, and gather. She sought out more planning courses, and by graduation she was pursuing planning positions in a smaller jurisdiction where she could help shape communities on the ground. “I had done internships in bigger cities like my hometown of Charlotte,” Sheild says, “but I really wanted to experience the breadth of what it takes to plan, design, and develop.”

Her first stop was Albemarle, a city of roughly 20,000 people nestled in central North Carolina. As a young planner there, Sheild found herself at the center of almost everything. “Nothing happened in that town that didn’t cross my desk at some point in the process,” she recalls fondly. Rezoning requests, downtown design decisions, small-business expansions, public hearings—she touched them all, eventually progressing into a senior planner position. Albemarle provided an intense, hands-on training in how policy, politics, and people collide at the local level. “It was an extremely rewarding endeavor,” she notes. “Because of the scale of the town, I really felt that I did have a positive impact.”

Amid the uncertainties of the pandemic, Sheild reflected on how graduate school could further her next career step. She explored the country’s top planning programs with the understanding that her education would be heavily shaped by the city in which she learned. For her and her fiancée, Boston emerged as a compelling possibility. The city’s architectural diversity—from Faneuil Hall to contemporary life sciences campuses—mirrored the kinds of tensions she was curious about: historic fabric and new growth, community needs and market pressures, local character and global capital.

The personalized experience of applying to Harvard’s Graduate School of Design cemented Sheild’s choice. Her contact with faculty and staff as a candidate for the Master of Urban Planning program provided crucial insight. “There was so much intentionality,” Sheilds recalls. “I could tell that they were curating our incoming class with a larger picture in mind, so our backgrounds and experiences fit together.” Seemingly small details made an equally strong impression, such as staff and faculty using her nickname, “Ellie,” instead of the formal “Elizabeth” on her application. “If they were putting that much effort into the admissions process,” Sheild states, “I knew they’d put that much effort into my education.”

The GSD transformed my life. I’m on a whole new path because of the people I met there, the projects I worked on, and the way the school encouraged me to think about cities.

Beginning at the GSD in 2021, Sheild dove headfirst into her MUP studies. Over the next two years, she worked as a research assistant for the Joint Center for Housing Studies , nursing a growing interest in affordable housing. She gravitated toward real estate courses as well, taking classes with Jerold Kayden, Frank Backus Williams Professor of Urban Planning and Design, and later serving as his teaching assistant. She also traveled to Portland, Oregon, for “Field Studies in Real Estate, Urban Planning, and Design,” a studio taught by Richard Peiser, Michael D. Spear Professor of Real Estate Development. The assignment involved the redevelopment of an aging 20-acre retail site, bringing together students with backgrounds in law, real estate, finance, and design.

Sheild’s experiences in the MUP program deepened her love for planning, but they also underscored its limits. From the public side of the table during her years at Albemarle, Sheild had often found herself negotiating with developers who ultimately controlled what did and didn’t get built. “For me, real estate was the tangible way to shape the community. And I realized that to be a successful steward for communities in the way I aspired, I needed more agency on the private side,” she explains. She began to imagine a career that would let her both write the “rules of the game” and help lead the team on the field.

That realization led Sheild to stay at the GSD for a second degree, joining the inaugural class of the school’s new Master in Real Estate program, established by Kayden. Being part of the first MRE cohort meant that she was surrounded by classmates from a wide range of backgrounds: architecture and planning, affordable housing, real estate investment, brokerage, and development. The mix of experiences among the students felt, to her, like a rehearsal for the real world. “In practice, you’re never in a room full of planners or a room full of designers,” she notes. “You’re working across disciplines all the time.”

While in the MRE program, Sheild had the good fortune to travel to Mumbai, India, with an option studio led by Rahul Mehrotra, John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization. In small, multidisciplinary teams, the students undertook large, complex urban redevelopment projects. Called “Mumbai INformal,” her team’s project reconceptualized the city’s dense urban fabric, putting forth high-rise podiums as layered structures that house residential, commercial, and civic spaces for a mix of income groups. After Sheild’s MRE graduation in November 2024, the remaining GSD students continued working on “Mumbai INformal,” with the project ultimately winning the 2025 Plimpton-Poorvu Design Prize.

Today, as an associate project manager at New England Development (NED), Sheild is putting her dual training to work on some of the Boston area’s most visible mixed-use projects. She joined the company after meeting GSD alumna and senior project manager Risa Meyers (MDes ’20) on a Harvard Real Estate Alumni Board tour; the connection turned into a series of informational conversations, then a job. “It was absolutely a GSD connection that opened the door,” Sheild says.

At NED—a family-owned firm with roots in the region dating back to the 1970s—Sheild works on a lean development team managing projects from entitlement through construction. Among the firm’s flagship efforts is Allston Yards , a multi-phase redevelopment that is transforming a sea of asphalt and a suburban-style shopping center into a new urban district with housing, retail, and civic space. For Sheild, one of the most meaningful elements is Rita Hester Green, a new one-acre public space—the first in Boston to be named for a Black trans woman. The project also contributes to a community benefits fund that distributes grants to local organizations.

Beyond Allston, Sheild is involved in projects in communities where her firm has been present for decades—including in her vicinity of East Cambridge. “Like my time in Ablemarle, I’m contributing to my neighborhood; I have a stake and an expertise. Looking out my window, I can see one NED project on the other side of I-93 and then another, CambridgeSide , just a stone’s throw from where I live. There’s a localism in what I’m doing,” Sheild says, “and I really enjoy that.”

Straddling planning and real estate means constantly negotiating between community aspirations and pro forma realities, between long-range visions and near-term constraints. For Sheild, that tension is the point. Her training at the GSD gave her a language for both worlds—the policy frameworks of planning and the financial logic of development—enabling her to advance real-world outcomes in the built environment.

Looking back, Sheild is unequivocal about the impact of those years in Gund Hall. “The GSD transformed my life,” she says. “I’m on a whole new path because of the people I met there, the projects I worked on, and the way the school encouraged me to think about cities.” From small-town North Carolina to a Boston development office, her work now connects policy and projects, numbers and neighborhoods, in the evolving landscapes of the communities she now helps to shape.

More Than a Roof: The Evolution of Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies

Housing is more than a roof overhead; it shapes our health, our wealth, our life chances, and the invisible lines of who belongs where. The Harvard University Joint Center for Housing Studies sits in the heart of that story. For more than six decades, this research hub—now affiliated with the Graduate School of Design and the Kennedy School—has traced how people live, what housing works and what doesn’t, and when smart policy can widen the circle of opportunity. Its data-rich reports on affordability, homeownership, and neighborhood change help set the agenda for city planners and advocates, lenders and lawmakers alike. And through convenings, fellowships, and cross-sector collaborations, the Center doesn’t just map the housing landscape; it asks us to imagine something better: a future in which decent, stable, affordable homes in thriving communities are a baseline, not a privilege.

Probing the Postwar City

The Center did not begin with a focus on housing. The Joint Center for Urban Studies of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard University, as it was first known, emerged from a larger mid-century effort to make sense of postwar America’s transforming cities—disinvestment, mass migration, rising poverty, and the slow fraying of urban life. A growing consensus held that only interdisciplinary research could grasp these forces and the nationwide urban decline they were fueling.

Harvard and MIT had each established their own centers for this work in the mid-1950s. When both turned to the Ford Foundation for support, the foundation brokered a merger, backing the new entity with grants that, over the next decade, totaled $2.1 million—about $18 million in today’s dollars. Thus, in 1959, the Joint Center for Urban Studies of MIT and Harvard was formally launched with a broad, three-part mission: to conduct research on cities and regions; to connect such research with practice; and to enhance related educational programs at both universities.

The Center’s leadership was deliberately split between Harvard and MIT. Harvard professor of city planning and urban research Martin Meyerson served as founding director, and MIT professor of land economics Lloyd Rodwin chaired the Center’s Faculty Advisory Committee. Both men had logged time in city planning offices and believed that the social sciences were essential to making planning and design responsive to real lives. Together, Meyerson and Rodwin built the Center’s distinctive interdisciplinary approach, drawing on economics, sociology, political science, and other fields to understand how cities actually work.

For its first decade, the Center operated as a kind of urban–intellectual exchange, what a 1964 publication described as “a discoverer and stimulator of talent, a generator of ideas, and a clearinghouse for scholars and funds.” Studies were carried out by Harvard and MIT faculty and graduate students, supported by a small staff tucked into an office on Church Street in Harvard Square. The research agenda was intentionally broad, mirroring its affiliates’ far-flung interests: urban demographic change, transportation systems, the decline of central business districts, even the design of an entirely new city (Ciudad Guayana in Venezuela).

The range of work shows up in the books that emerged from those early years. In the first five alone, the Center produced a remarkable ten books and thirty papers, including Kevin Lynch’s The Image of the City (1960), Nathan Glazer and Daniel P. Moynihan’s Beyond the Melting Pot (1963), Edward C. Banfield and James Q. Wilson’s City Politics (1963), and Charles Abrams’s Man’s Struggle for Shelter in an Urbanizing World (1964). Together, these and other seminal works helped establish the Center as a place where ideas about cities could be tested, contested, and widely disseminated.

In keeping with its mandate, the Center cultivated conversations not only across disciplines but also between researchers and people making decisions on the ground. One such event took place in 1968, when architect J. Max Bond Jr. (AB ’55, MArch ’58) returned to his alma mater to argue for a different kind of urban renewal—one driven by communities themselves rather than by the top-down projects then remaking American downtowns and ousting Black, immigrant, and older residents.

Bond found a receptive audience at the Center. Just a few years earlier, it had published Martin Anderson’s The Federal Bulldozer: A Critical Analysis of Urban Renewal, 1949–1962 , a searing critique of the government’s urban renewal program and its human costs. In 1966, it followed with Urban Renewal: The Record and the Controversy, edited by James Q. Wilson, which offered a measured overview of the policy’s contested benefits and harms.

This focus on people and place—on how lives are shaped by streets, buildings, neighborhoods—ran through the Center’s work. Its “interdisciplinary approach,” as one account put it, “placed the city in a total social and political context and paid close attention to the interaction of people and their environment.” Even before housing became its central analytical focus, the Center was laying the groundwork for its later concentration on the lived experience of home.

Housing Takes the Lead

By the late 1960s, even as former President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs faced restructuring, a national argument persisted over what the government owed its citizens in the way of a decent home and a livable environment. Around the same time, the initial Ford Foundation funding for the Center ceased, forcing a hard look at how the institution would support itself. Under the guidance of labor economist John T. Dunlop, then dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and future US secretary of labor, the Center refocused its attention on “specific urban problems ” in place of the broad general research that characterized its earlier years, starting with housing—a timely subject that sat squarely between theory and practice.

Housing became the lens for a wider set of questions. The Center began to pair policy analysis with research into aspects such on housing markets, construction, and development, and it pulled in voices from outside the university—public officials, private developers, nonprofit advocates—to help shape the work.

To give those partnerships a home—and to shore up its finances—the Center created its Policy Advisory Board (PAB) in 1971, bringing together a coalition of major players from across the housing industry. The original group included about twenty corporate members; today, there are nearly sixty, including companies such as Home Depot , Sherwin-Williams Company , Kohler Co. , and Lennar . In return for financial support, PAB members take part in semiannual meetings where scholars, government officials, and industry leaders discuss emerging trends and concerns in housing. This arrangement is deliberately mutual: it gives firms access to cutting-edge research and candid conversation while providing researchers with insights from key entities involved in housing. In addition, it offered the Center a stable base of funding, financially independent from its parent universities.

In 1985, the Joint Center for Urban Studies made its priorities explicit and renamed itself the Joint Center for Housing Studies. The shift from “urban” to “housing” signaled more than a change in branding. Over the next few years, the Center wound down its doctoral fellowship and executive-education programs, both products of the 1970s, and day-to-day oversight moved from high-level university administrators to the deans of Harvard’s Kennedy School and MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning.

Before long, diverging priorities prompted Harvard and MIT to part ways. By 1989, the Center had become a Harvard institution, jointly anchored in the Kennedy School and the Graduate School of Design (GSD). In the early 1990s, it sat institutionally and physically within the Kennedy School; in 1996, it formally shifted to the GSD and would go on to occupy a series of offices in Harvard Square, where it remains today.

Signature Reports and Expanded Impact

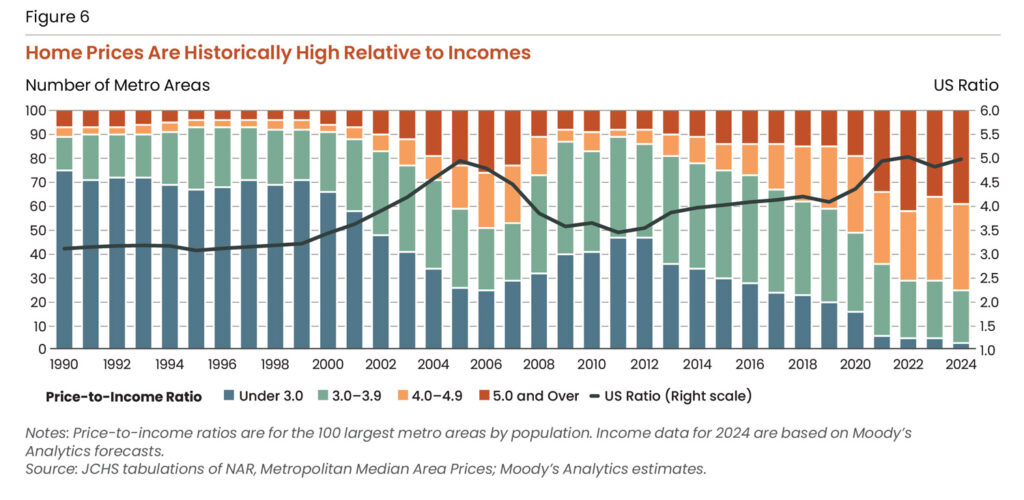

The Center’s visibility took a major leap in 1988 with the debut of its flagship publication, The State of the Nation’s Housing . This annual report—which for many years was supported by the Center’s original funder, the Ford Foundation—tracks recent trends and emerging challenges in US housing markets and forecasts what may lie ahead in the coming year. Drawing on years of survey data from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, population surveys from the Census Bureau, and other sources, the first report opened with a stark verdict on the state of housing in 1988: America was increasingly becoming “a nation of housing haves and have-nots.” Most homeowners were comfortably housed and had built substantial equity in their properties, but that prosperity bore little resemblance to the experience of a growing share of low- and moderate-income households, who faced high costs just to secure minimally adequate homes.

From there, the 1988 report laid out its findings in text and graphics, tracing regional patterns in ownership and renting, cost burdens, housing quality and availability, age and family type, and differences between urban and rural areas. The picture was sobering: homeownership costs were high; ownership rates had fallen, especially for younger households; rents kept climbing and claimed an ever-larger share of household income; only about a quarter of low-income households received public or subsidized assistance; and rising numbers of people were living in substandard housing—or had no housing at all. With this first report, the Center set out “to document these diverse housing problems and provide a sound empirical foundation for the emerging national housing policy debate.”

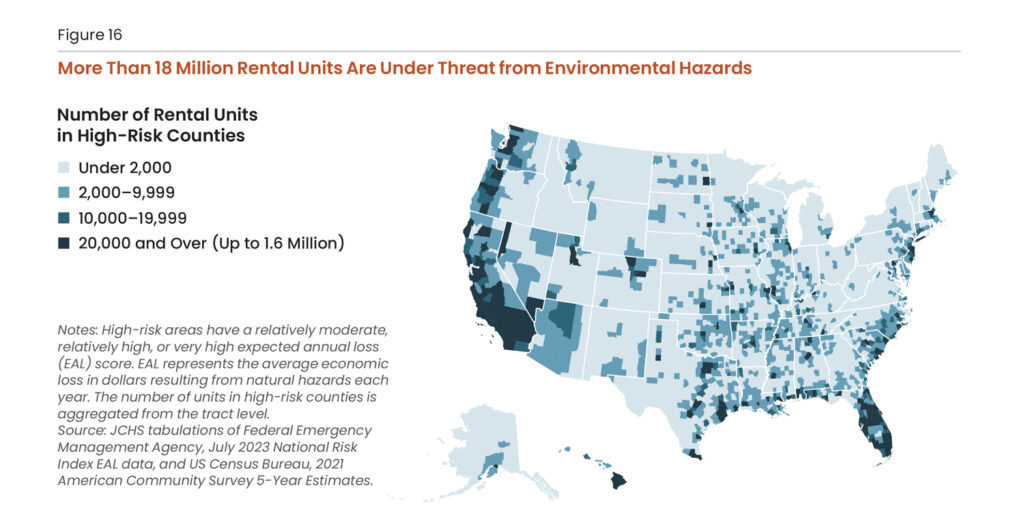

For more than thirty-five years, the Center has continued to publish The State of the Nation’s Housing , cementing its reputation as a go-to source on US housing markets. Over time, it has also carved out more specialized lines of inquiry, producing additional signature reports on specific corners of the housing world. In 1995, responding to a boom in home renovation, the Center launched the Remodeling Futures Program, which tracks trends in the remodeling industry and, beginning in 1999, has issued the biennial Improving America’s Housing report. In recent years, that work has expanded to explore how climate change is reshaping the nation’s existing housing stock. Likewise, the first America’s Rental Housing report appeared in 2006, offering a recurring, in-depth look at the rental market. And in 2022, the Center created the Housing an Aging Society Program, which had released its first report, Housing America’s Older Adults , in 2014.

That same year, the Center launched its newest series, The State of Housing Design , edited by Chris Herbert , managing director of the Joint Center for Housing Studies and lecturer in urban planning and design; Daniel D’Oca (MUP ’02), associate professor in practice of urban planning; and former GSD Druker Fellow Sam Naylor (MAUD ’21). (Recent GSD graduate Aaron Smithson [MArch/MUP ’25] is now working with the editors to produce the second edition, due in 2026). The book-length publication, Herbert notes , leverages the GSD’s design expertise “to call attention to the important role that design can and must play in addressing the housing challenges we face as a nation.” Departing from the primarily quantitative research of the Center’s other reports, The State of Housing Design gathers essays by leading scholars and practitioners—including GSD dean Sarah Whiting, professor Farshid Moussavi, and critic Mimi Zeiger—on how residential design intersects with issues such as sustainability, density, and social cohesion. Taken together, these publications have reshaped not only how we understand housing, but also how the Center positions itself—as a bridge between data and design, policy and practice, and the academy and the wider public.

The Center Today: Connecting with the GSD, the Harvard Community, and Beyond

More than sixty years after its founding, the Center remains committed to advancing rigorous research, mentoring students, and fostering informed public debate on housing. “We understand ourselves to be an intersection between research and the worlds of practice, policy discussions, and encouraging students,” says David Luberoff , the Center’s director of Fellowships and Events.

Where the early Center was essentially a loose constellation of faculty pursuing their own urban-studies projects, today it is a twenty-one-person operation, with full-time researchers, fellows, and administrative staff. Alongside its signature reports and other publications, the Center runs a robust outreach program built around teaching, financial support, and policy engagement. Each year, staff teach two core housing-focused courses cross-listed at the GSD and Kennedy School. The Center also annually funds two to three GSD option studios engaged with housing; roughly twenty summer fellowships for Harvard graduate students working on housing challenges in public, nonprofit, and for-profit settings; and about a dozen additional fellowships and research grants across the university for students focused on housing issues.

The public side of the work is equally expansive. In the past year alone, the Center hosted more than thirty events that drew over 16,000 in-person and online attendees. In 2024–2025, its research was cited in nearly a dozen testimonies before US House and Senate committees, and media outlets across the country referenced its findings more than 20,000 times—a measure of how deeply the Center’s work now shapes housing conversations nationwide.

As an autonomously funded entity affiliated with both the GSD and the Kennedy School, the Center occupies a distinctive niche in Harvard’s ecosystem—financially beholden to neither school yet intent on staying closely linked to each. Herbert, who has led the Center since 2014, puts it this way: “We create collaborations with faculty that define a mutual interest. We may look at it through one lens, they may look through another, but we’re looking at the same thing.”

One of the strongest ties between the Center and the GSD is the Faculty Advisory Committee (FAC), which, in various iterations, has been part of the Center’s governance since its founding in 1959. Today, the FAC includes nine professors—seven from the GSD and two from the Kennedy School. Chaired by D’Oca, the FAC functions as both sounding board and bridge, aligning the Center’s research agenda with the GSD’s pedagogical and design priorities.

A symposium held at Harvard in September 2018, Slums: New Visions for an Enduring Global Phenomenon , stands as a prime example of collaboration between the Center and the GSD. Organized in part by FAC member Rahul Mehrotra (MAUD ’87; John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization), in partnership with the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy , the conference examined the physical, political, and economic realities of slums worldwide. “That was an important touchpoint where we engaged with the GSD on bringing design into conversation with the policy and market analysis that the Center does,” Herbert recalls.

Another noteworthy collaboration followed in 2020, when the Center and the Loeb Fellowship Program cosponsored In Pursuit of Equitable Development: Lessons from Washington, Detroit, and Boston , a half-day event devoted to ensuring that low- and moderate-income households would benefit from new development in their communities.

In the past few years, the Center has looked to tighten its ties with the GSD through new appointments. Herbert references research fellow Susanne Schindler , who joined the Center in 2024. Trained as an architect and a historian of the intersections among architecture, finance, and housing, Schindler “bridges the gap between the design and policy worlds,” he notes. She was instrumental in organizing a spring 2025 half-day event, The Evolving Landscape of Social Housing in New England , and she is currently examining the ways that redevelopment authorities might support the creation of affordable housing.

For Herbert, Schindler’s role reflects a larger ambition. “We look to collaborate across the university, not only with the GSD and the Kennedy School. We’re a center focused on housing, and housing is not a discipline; it’s an object of study. And there are many reasons why every school at Harvard—the law school, business school, and more—should care about housing.”

The Center plans to further magnify its presence by spanning these silos. Over the last year, it has teamed with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Initiative on Health and Homelessness and the HKS Government Performance Lab on multidisciplinary events addressing homelessness. While not always easy to coordinate, “these cross-collaborations bring many benefits,” Herbert acknowledges. “We’ve made progress over the last decade, and there is more to come.” For the Center, collaboration is not an add-on; it is the method by which ideas about housing move into the world.

From its origins as an urban think tank puzzling over postwar cities to its current role as a leading voice on housing markets, policy, and design, the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies has continually adapted to match the scale and urgency of the problems it confronts. Its work has followed people from streets and slums to suburbs and older adult housing, from national statistics to neighborhood-scale interventions, looking to address housing challenges and foster the next generation of housing leaders. As rising inequality, climate change, demographic shifts, and widening affordability gaps reshape notions of home, the Center’s blend of rigorous research, design-minded inquiry, and cross-sector collaboration offers a rare kind of infrastructure: one built not of bricks or beams, but of knowledge, relationships, and the stubborn belief that a decent place to live should be something more than a matter of luck.

*The author thanks Kerry Donahue, Chris Herbert, David Luberoff, and Susanne Schindler for sharing their knowledge about the Center’s history and present-day activities.

Additional Resources

Eugenie Birch, “Making Urban Research Intellectually Respectable: Martin Meyerson and the Joint Center for Urban Studies of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University 1959–1964 ,” Journal of Planning History vol. 10, no. 3 (2011), 219–238.

Peter Ekman, Timing the Future Metropolis: Foresight, Knowledge, and Doubt in America’s Postwar Urbanism (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2024).

The Joint Center for Urban Studies of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, The First Five Years: 1959–1964 (Cambridge, MA:1964).

Christopher Loss, “‘The City of Tomorrow Must Reckon with the Lives and Living Habits or Human Beings’: The Joint Center for Urban Studies Goes to Venezuela, 1957–1969,” Journal of Urban History vol. 47, no. 3 (2021), 623–650.

Christopher Loss, “Remapping the Midcentury Metropolis: The Ford Foundation and the JCUS of MIT and Harvard University ,” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports Online (2014).

Remembering Lars Lerup (1940–2025)

Lars Lerup was perhaps the most provocative urban thinker of his time. With an unconventional blend of inquisitive observation and wild speculation—aided by a dual gift for clarity and hyperbole—his prolific graphic and written output shaped the way we understand the American city. A towering figure in academia, his life and work touched countless individuals across several generations. A charismatic man with a warm and expansive personality, he leaves behind many friends.

Lars was born in 1940 in Växjö, Sweden. He often recalled his childhood, in the outskirts of a small town, at the edge of the northern taiga, as marked by the dual influence of the immensity of the forest and an emotionally absent father. He left home for Stockholm at age sixteen to pursue studies in civil engineering. Soon after graduating in 1960, Lars moved to the United States, where he studied architecture, obtaining a degree from the University of California, Berkeley in 1968. He continued his studies at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), where he graduated with a MAUD in 1970.

During the 1970s and ’80s Lars was based in Berkeley, where he taught for two decades, but he remained involved in the ongoing debates on the East Coast, acting as a bridge between both centers of architectural discourse in the country. During this period, he was an active participant in Peter Eisenman’s Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, contributed one of the seminal issues to Steven Holl’s Pamphlet Architecture, and was a regular visitor at the GSD.

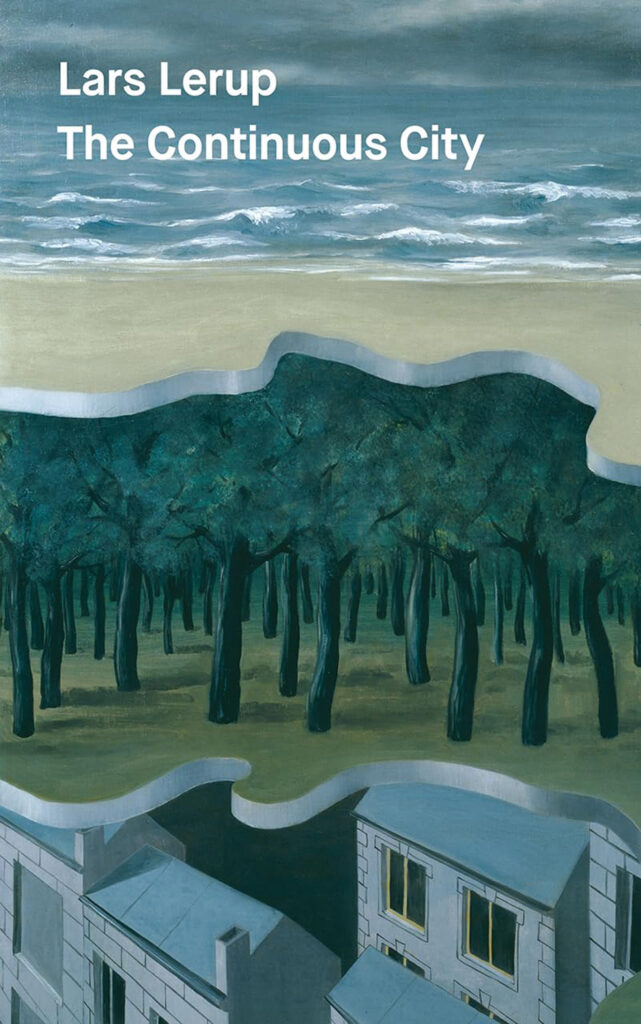

In 1993 Lars moved to Houston, Texas, to become the dean of the Rice School of Architecture. Once there, he brought a cadre of free-wheeling collaborators who, for a few years, created a buzzing atmosphere of experimentation. Living in the quintessential postwar, car-centric American city was a puzzling experience for the Swede, who gradually turned Houston into the crux of his writing on contemporary cities. Starting with his article “Stim & Dross,” published in Assemblage in 1994, Houston continued to gain centrality in Lars’s thinking, becoming the subject of several books, including After the City (2000), One Million Acres & No Zoning (2011), and The Continuous City (2018).

As I wrote in the introduction to that latter publication, Lars’s way of thinking and writing about the city could be described as a hunter–gatherer empiricism: it departed from observations of objects and phenomena in the real world to theorize them—first by naming them, and then by setting them into relationships with other objects or phenomena, as if building a collection of fragments that formed a system of sorts. Lars’s systems were full of gaps and fissures, and their components, even if interdependent, always retained their discreteness and autonomy.

This approach was especially useful when applied to the study of contemporary cities, vast assemblages where boundaries between things are ambiguous, often overlapped or nested within each other, and where it is hard to tell how or to what extent parts integrate into larger wholes, or even decipher the scales of the relationships at work. Lars’s refusal to overtheorize or simplify the level of complexity of urban conditions was his primary contribution, and it kept his thinking and writing sharp for decades.

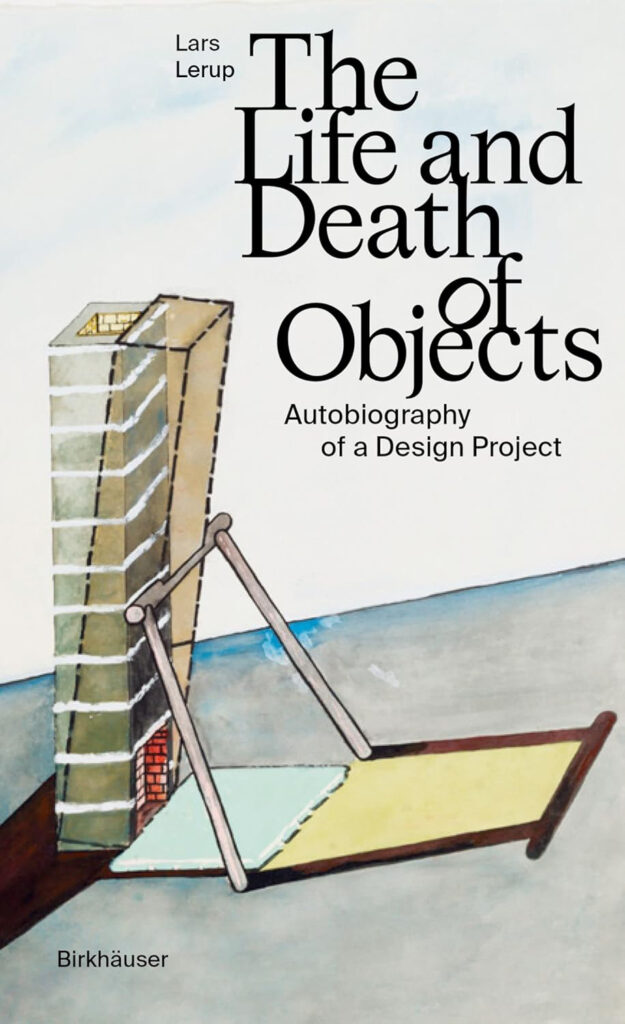

Cities where, however, not the only topic of interest for Lars, who had an eclectic list of obsessions and recurring themes, which included everything from furniture to geological formations. Often he explored these preoccupations through speculative designs and through his drawing practice, which was equal in originality and relevance to his writing.

As a man, Lars was, like many of us, full of contradictions. He was open-hearted but elusive, expansive but vulnerable, a loner but deeply devoted to family—he adored his son, Darius, and his wife, Eva. He was a workaholic but also lazy as only a hedonist can be. . . . Perhaps more than anything he was large, as in larger-than-life: he took up a lot of space in the lives of the people around him. It is unavoidable that when somebody like that departs, they leave behind a void commensurate with the impact they made in others. In the case of Lars, the gaping void we feel is mitigated by myriad memories of his wit and charming intellect, as well as by a body of work that helps us make better sense of the world in which we live.

About Jesús Vassallo:

Jesús Vassallo is a registered architect and an associate professor at Rice University.

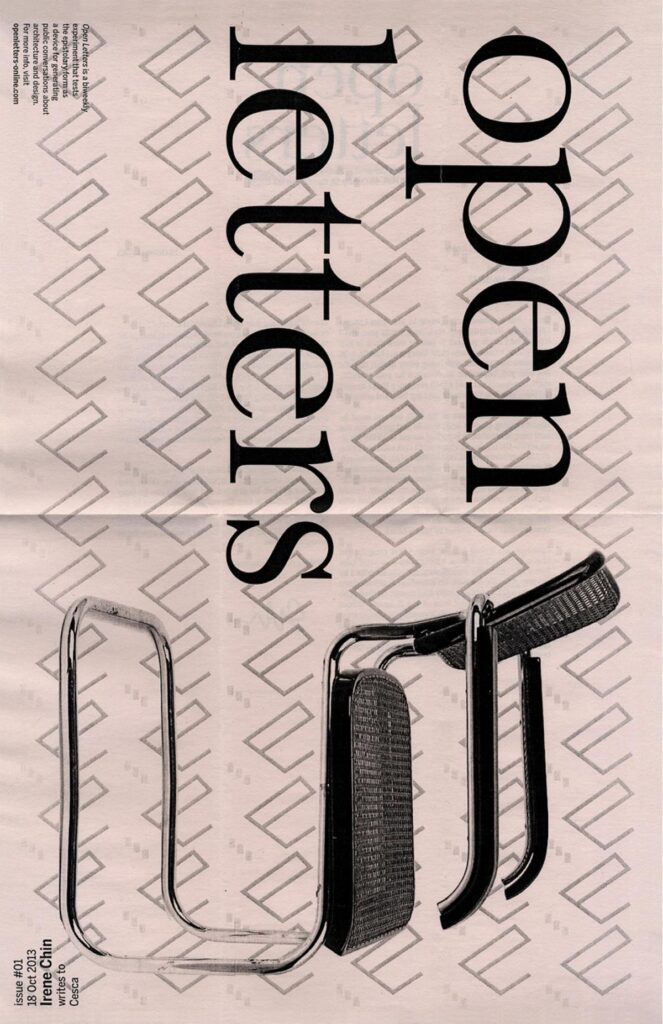

Student Journals Recount the GSD’s Intellectual History

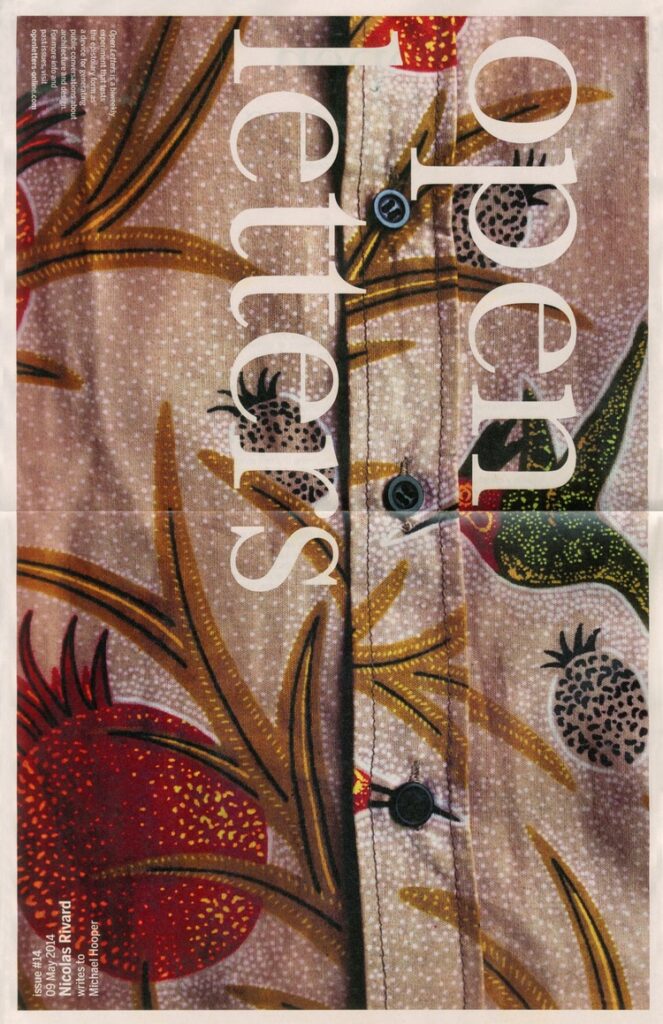

When Cam My Nguyen, a first-year architecture student, was applying to the Graduate School of Design (GSD), she learned about one of the School’s student journals, Open Letters , which invites students, staff, and faculty to engage in public discourse about design in the epistolary form. This fall, Nguyen helped organize an exhibition of archival issues of Open Letters in the student-run Quotes Gallery . The history of the publication was also the subject of a separate event in the Frances Loeb Library Special Collections that celebrated the long history of student journals at the GSD.

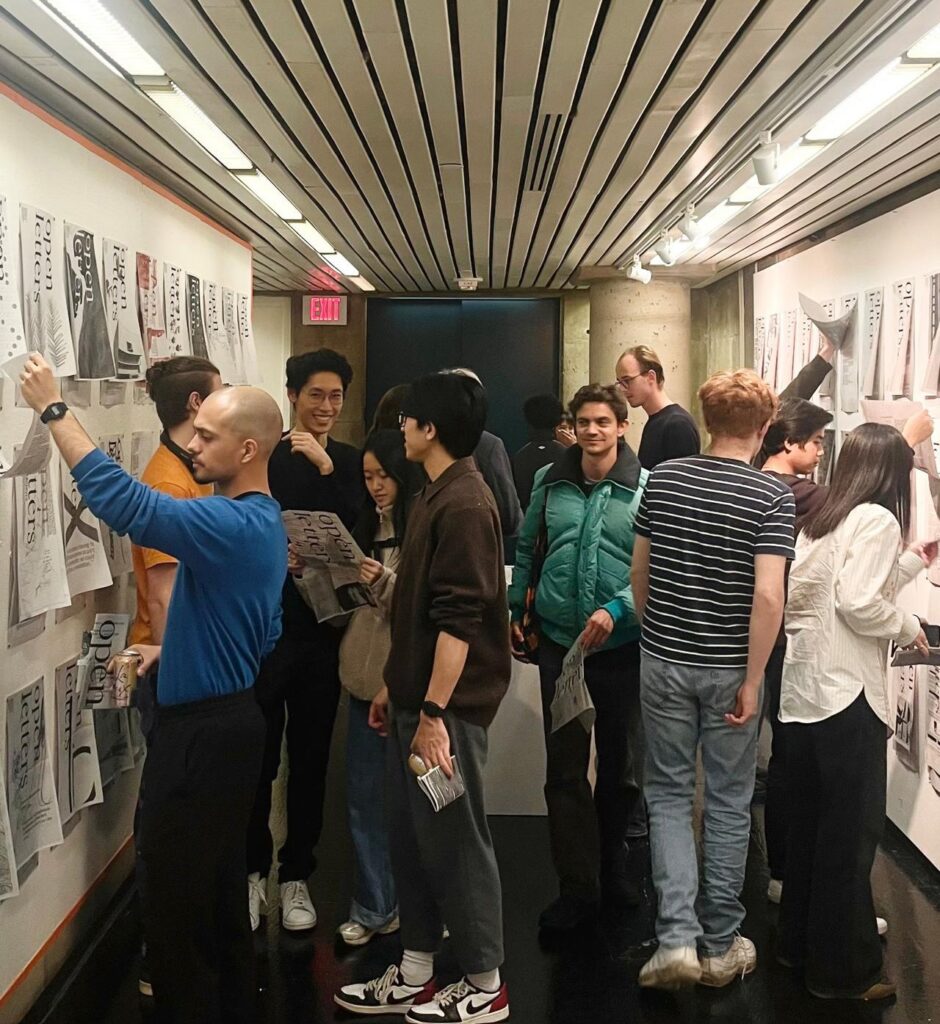

Nguyen’s interest in the journal rose out of her passion for the letter as a narrative device. She grew up reading Edgar Allen Poe’s collected letters, Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic, and Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, and was part of the last class of students at her elementary school who were taught to write cursive; she’s always hand-written letters to friends. So, in her first year at the GSD this fall, she immediately sought out Open Letters, joining its staff and working with two other students, Simona Evtimova (MArch ’29) and Hazel Flaherty (MArch ’29), to design the exhibition. The show included copies of all 102 issues the journal has published since its founding in 2013. Issues were hung side by side in the Quotes Gallery so that visitors could peruse and read each letter, flipping up the pages one by one.

Since its inception, the topics in the journal’s letters have range d from “love letters, anonymous letters, curriculum proposal letters, letters of admiration and letters of discontent,” writes special collections curator Inés Zalduendo in the Special Collections’ guide to their collection of student journals. Open Letters’ founder, Chelsea Spencer, was inspired to launch the journal after reading a letter from Mack Scogin, Kajima Professor in Practice of Architecture, Emeritus, to architect Benedetta Tagliabue, about her Barcelona home, in Harvard Design Magazine No. 35. In the inaugural Open Letters, Spencer wrote to Mack Scogin , explaining the premise for the journal and speaking to her history with him and his partner and wife, Merrill Elam.

“I’d tell you,” writes Spencer, “we wanted to pry open the gap between the stilted obfuscation of Academic English and the sloppy narcissism of Internetspeak, with the ambition of creating a space for slow, sincere correspondence.” She adds at the end, “P.S. I’m blaming you if this whole thing turns out to be a waste of paper.” In fact, it would go on to be the School’s longest-running student journal.

Over the years, the journal’s letter writers have grappled with many topics, “from the history of architecture,” noted Nguyen, “to a secret admirer writing to a crush.” Some are more experimental than others, she said. One person wrote to their unborn son, another to beds. One of her favorites is an exchange between Cameron Wu and Milos Mladenovic in 2017 and 2018. Mladenovic (MArch ’20) first wrote to Wu in 2017, when Wu served as assistant professor of architecture at the GSD. Mladenovic was grappling with his sources of inspiration and commitment to his projects as a student, and his reliance on “the essential dialectics of architecture” that Wu had taught in that semester’s studio course. Wu responded when Mladenovic was wrapping up his last semester at the School, offering advice to his student about his projects.

“What I found productive,” Nguyen noted, “is the very critical (almost combative) position that the letter format allows one to take. I’m advocating for generative conversations, especially in the face of opposing ideologies.”

Nguyen explained that, when she was an undergraduate at Princeton, Wu was her mentor. While she’d known how influential Wu was in the core studios at the GSD, as a new student at the School reading Open Letters, she found it “really exciting to see a thread through the very different pedagogies of Princeton and Harvard.”

This year, the biweekly Open Letters will include a letter from Mae Dessauvage (MArch ’21), a trans woman addressing her pre-transition self, “M,” when she was a student at the GSD.

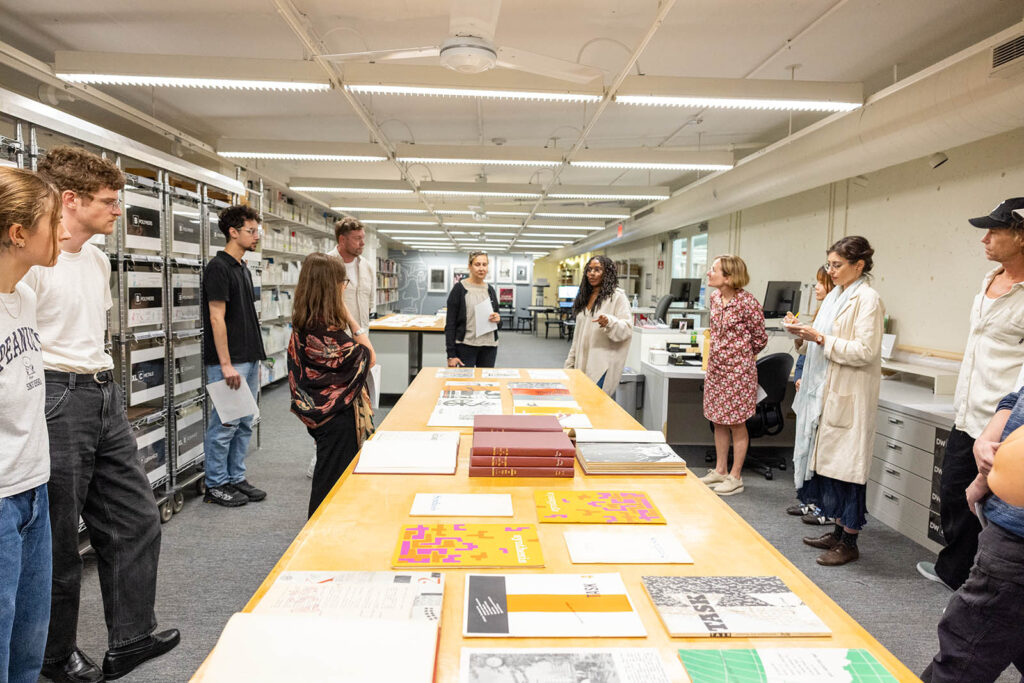

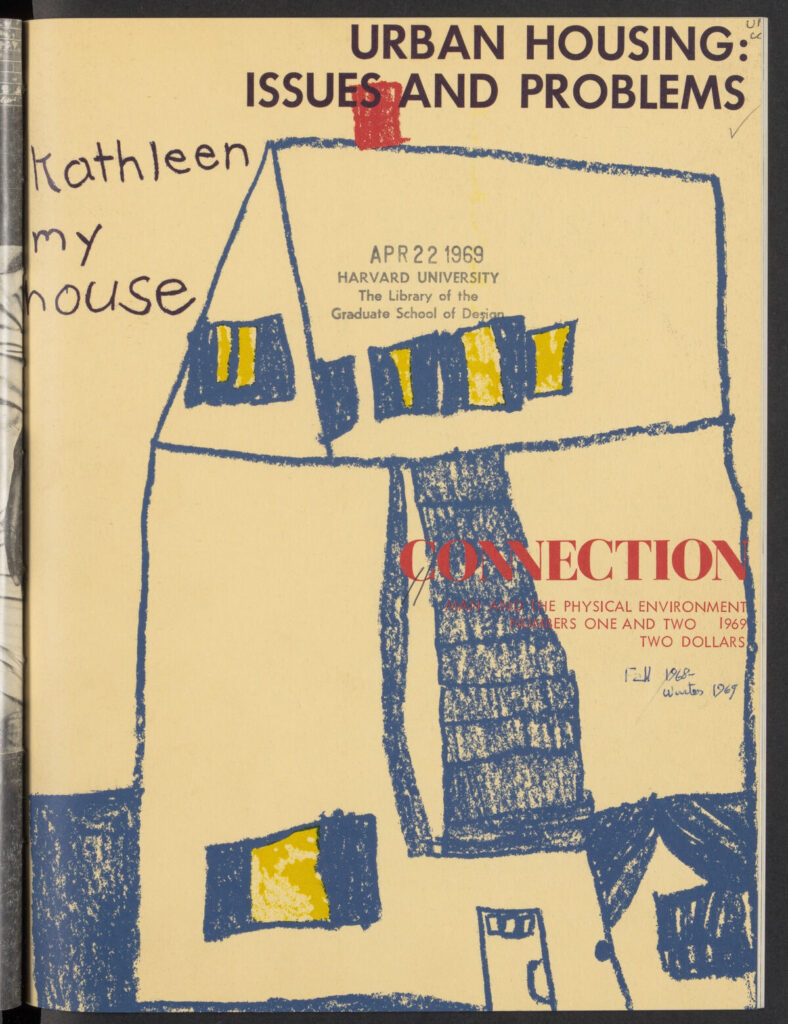

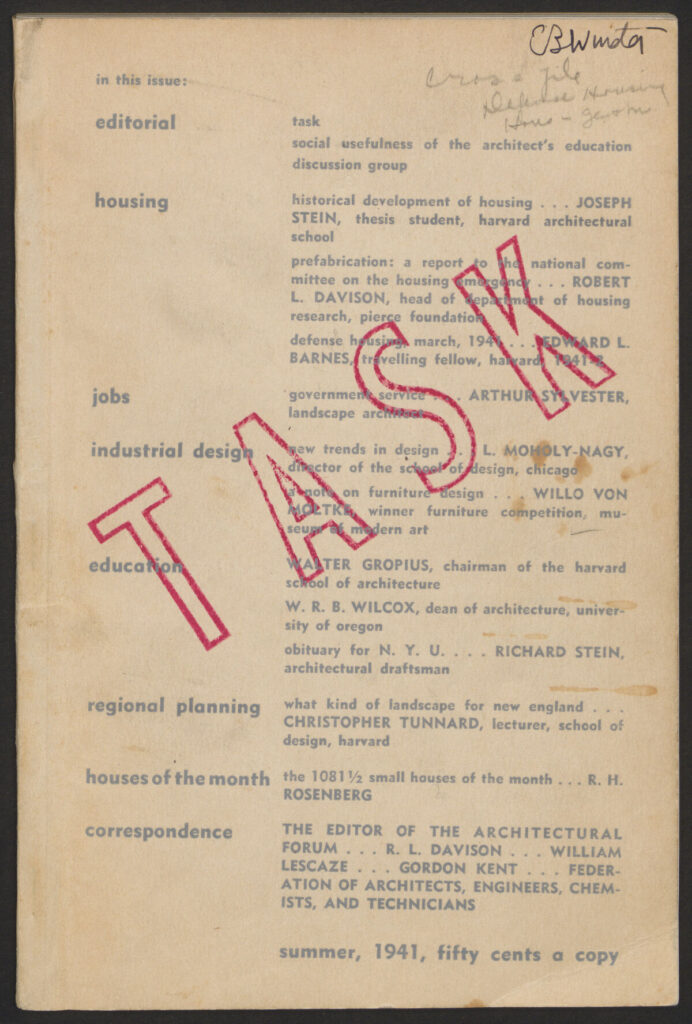

The journal was also recognized as an important part of the history of student publications at the GSD. This fall, during an “archives party ,” an event during which attendees examined various archival documents and publications in the Special Collections Reading Room at the GSD’s Frances Loeb Library, special collections curator Inés Zalduendo and archival collections website editor Ashleigh Brady (MArch ’26) featured the wide range of student publications that are part of the GSD’s history, starting with TASK: A Magazine for the Younger Generation in Architecture , first published in 1941. In addition, Loeb Fellow Andy Summers delivered a presentation on his work to document student journals in Scotland. In partnership with Priscilla Mariani, access services specialist, Zalduendo and Brady have made the GSD student publications available to read online , with the guide written by Zalduendo.

“Since its founding in 1936,” writes Zalduendo, “students at the GSD have produced at least 17 different student publications.”

The journals mark not only the School’s culture and students’ “landscape of inquiry,” Zalduendo writes, but also offer a window into our national and global history. For example, TASK includes writing by Dean Joseph Hudnut and professor Walter Gropius; Synthesis (1957–1958) reflects Dean Josep Lluís Sert’s years and Jacqueline Tyrwhitt’s work to found a program in urban design at the GSD; Connection (1963–1969) documents visual arts at the GSD and other Harvard schools, and includes a photographic series of the 1969 beating of Harvard students by local police during a Vietnam War protest; and, the first issue of APPENDX: Culture/Theory/Praxis , published in 1993, includes an argument by editors Darrell Fields, then a Harvard PhD student (he’d go on to earn his MArch at the GSD), and Kevin L. Fuller (MArch ’92) calling attention to the dearth of diverse representation in the field.

“We, the editors, are not shouting to be included in the academy—indeed, we are already here,” they write. “We are more interested in conveying, from our various positions, our insights and experiences from within the discipline in order that these essential positions not continue to be overlooked….” The journal was intended to include space for their voices and others in the field who were overlooked or unheard.

Zalduendo’s summaries of the School’s student journals highlight almost a century of thinkers and designers at the GSD who helped advance public discourse around design, consider the School’s pedagogy and curricula, expose systemic gaps and inequities, and highlight the ideas and works swirling through the trays each semester.

The history of student journals has also been documented in the School’s publication, Platform, which “represents a year in the life of the GSD.” Issue 12, “How About Now?” covers 2018–2019, and includes a curated overview of several student journals, including Open Letters. Editors Carrie Bly (MDes ’19), Isabella Caterina Frontado (MLA, MDes ’20), and Natasha Hicks (MUP, MDes ’19) write that “GSD students have consistently sought to process their intellectual inheritance in order to evaluate their position as designers within and beyond the School.”

Leyla Uysal: Weaving Culture, Ecology, and Design at the GSD

When Leyla Uysal (MDes ’24, MLA ’27) arrived at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), she was already navigating an extraordinary path. An urban planner, entrepreneur, and mother, she had long worked to uplift Kurdish communities in her native Türkiye. Yet it was at Harvard that her journey deepened—becoming, as she puts it, “a dialogue with nature, design, and the world itself.” Through the Master of Design (MDes) and now the Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) programs, Uysal has found the GSD to be a catalyst for reimagining how creativity, culture, and ecology can intertwine to shape more compassionate and sustainable futures.

“Since my childhood, I’ve lived in close conversation with nature,” Uysal says, reflecting on her Indigenous Mesopotamian upbringing in a war-scarred area of rural Türkiye. Her Kurdish community—long oppressed by mainstream society—remained largely untouched by modernization, preserving a way of life rooted in intimacy with the land. What might have been deprivation became, in hindsight, a kind of inheritance. “Not being introduced to modernization, globalization, and industrialization has a positive impact on our bond with nature,” she explains. “We see everything as valuable and precious, and we live with much less waste. This is the blessing of not being fully modernized.”

This blessing, however, came at a cost. Education was not a birthright in Uysal’s community; it was something to be won. As a girl, she had to persuade her parents to allow her to attend school, defying customs that deemed education improper for daughters. “This was the curse of not living in a modernized setting,” she recalls. “My going to school was seen as dishonoring my culture.” Within her tribe of nearly six thousand people, Uysal became the first woman to graduate from high school—and the first person ever to attend college. Today, she notes with pride, many of her younger female relatives have followed in her path.

In time, Uysal left her family homestead for Istanbul, where she enrolled at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University. There she earned a bachelor’s degree in urban and regional planning while also studying ecology and ecosystem restoration—a synthesis that would become central to her later work. In 2012, she moved to Boston with two goals: to learn English and, inspired by Charles Waldheim’s theories of landscape urbanism, to explore opportunities for study at the GSD. Marriage and motherhood followed, and for a few years her energy turned inward, toward family and the fragile equilibrium of building a new life abroad. But the memory of her own struggles lingered. “I wanted to help others who were facing the same challenges I did,” she says.

Photo: Brian McWilliams.

That impulse gave rise to Bajer Watches , a social enterprise founded, in her words, “to empower women and children, to provide them opportunities to have a better life.” Through Bajer, which produces high-end timepieces, Uysal partners with two Turkish NGOs that create educational and employment opportunities for rural Kurdish women and children. Each watch, crafted by hand, carries a piece of that story: the leather bands are inscribed with motifs drawn from Kurdish rugs—ancient symbols of clarity, resistance, and protection once woven by women as a means of communication when traditions required their silence. “The brand brings that story to the front line,” Uysal says. “Through design and craft, we tell the world that we exist.”

Bajer soon drew attention from the press , its blend of activism and aesthetics striking a resonant chord. Yet even as her company grew, Uysal felt another calling stirring. The planner in her—the thinker who saw systems, cities, and landscapes as interconnected—was restless. “I thought, I need to go back to school,” she recalls, “and use my skills for the next generations.”

In 2022, Uysal returned to academia, enrolling in the MDes program at the Harvard GSD. It marked, as she puts it, “a beautiful new chapter in my life.” She had always felt close to nature, but the MDes program gave that intuition an intellectual framework. As a student in the Ecologies domain, she immersed herself in the science of climate systems, exploring how data, policy, and design intersect. “I took many science, data, policy, and technology classes in the context of climate change,” she says. “My perspective became more grounded, and now everything I do is rooted in it.”

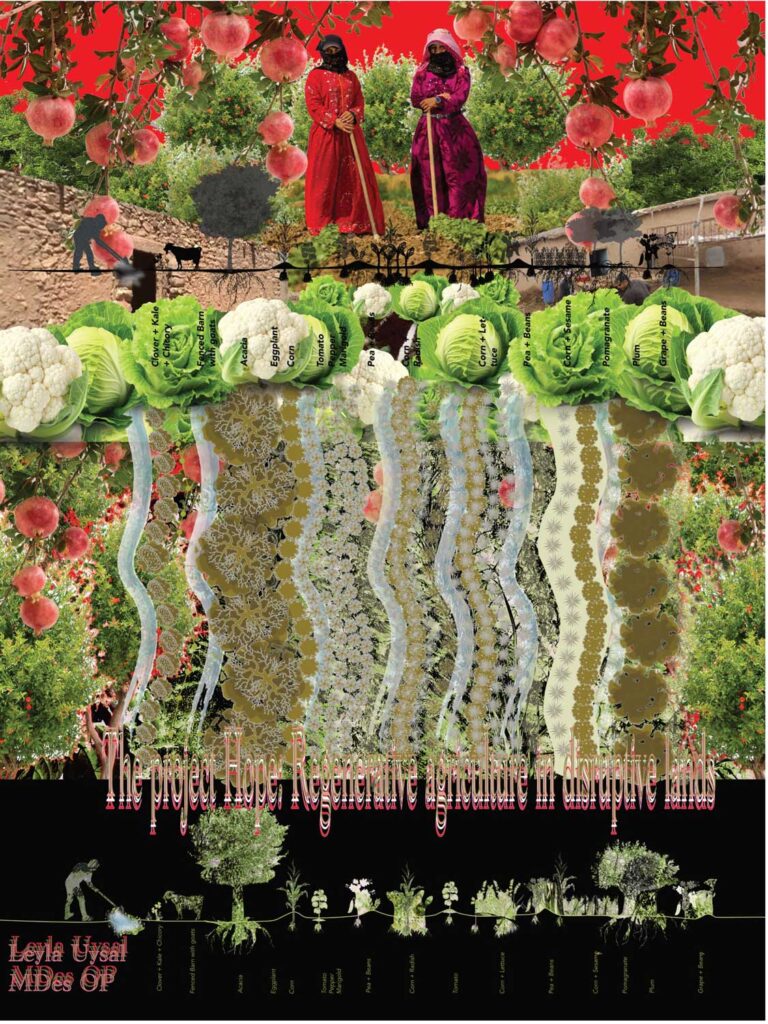

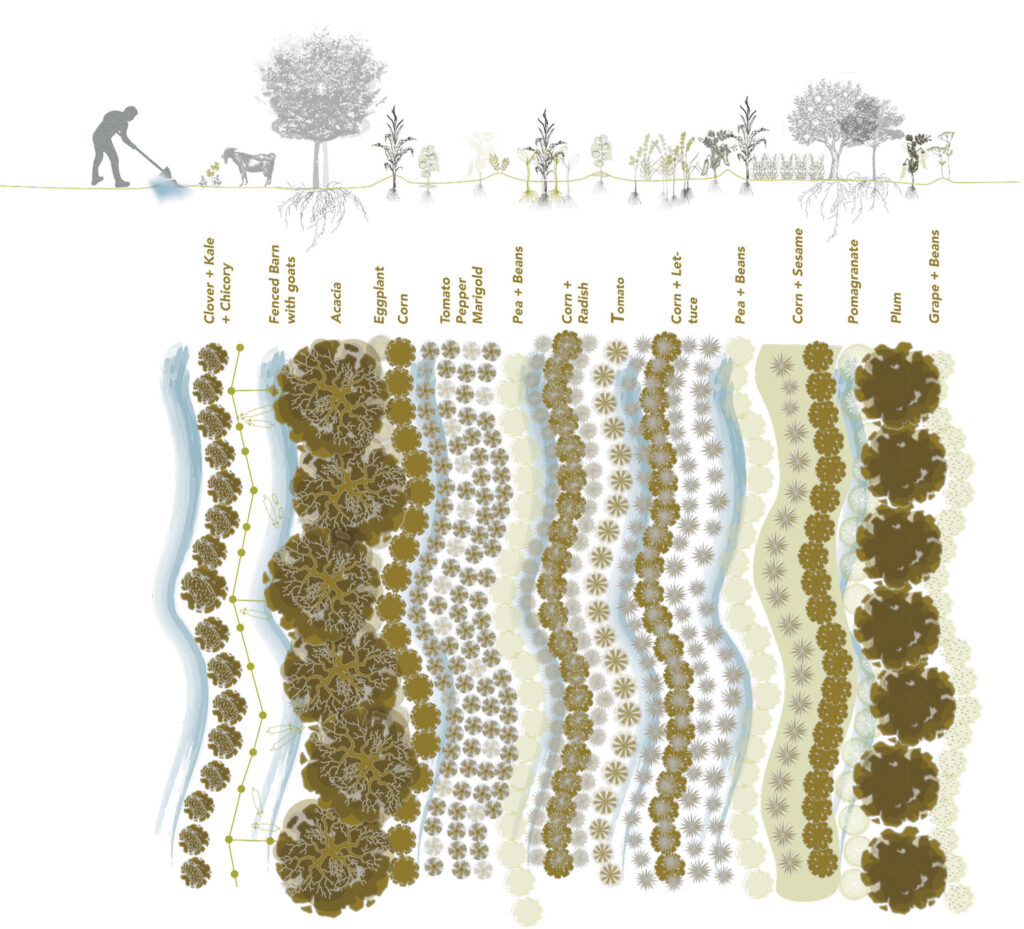

Her studies coalesced in “Project of Hope: Re-Imagining Indigenous Lands; Recovering through Memory,” supported by the Penny White Project Fund. “Project Hope” addresses the landmines scattered along Türkiye’s Syrian, Iraqi, and Iranian borders—about two million buried among ancient olive and pistachio fields—that have scarred both the land and its people. Rooted in a desire to restore memory and livelihood, the project uses landscape and permaculture design as tools to help Kurds reconnect with their sustainable farming traditions and reclaim their way of life. The work blended design, ecology, and cultural memory, proposing ways Indigenous landscapes might be repossessed—not only physically, but emotionally and symbolically.

After completing the MDes in 2024, Uysal’s curiosity only deepened. That summer, she began a PhD in environmental planning and policy program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), under the guidance of professors Janelle Knox-Hayes and Lawrence Susskind . Her research, ambitious in scope, examines the role of human ego in design and planning, exploring how humility and reciprocity might reshape zoning, development, and our relationship to land. “It’s about rethinking how we plan on this planet,” she says—a question that links the human scale of design to the vastness of the Earth itself.

The complexity of that inquiry soon drew her back to landscape itself. In the fall of 2025, Uysal enrolled in the MLA program at the GSD, supported by a full scholarship from the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture. She describes the MLA as a foundation for her doctoral research—a way to integrate lived experience with ecological design. “It allows me to build a more inclusive, Earth-oriented, future-oriented approach,” she says, “to inspire planners, architects, and designers to rethink their work.”

This year, she added yet another layer to her work: teaching. At MIT, she is a teaching assistant for a course on quantitative and qualitative research methodologies—a role she approaches not as an authority, but as a participant in an ongoing exchange. “I’m still learning,” she says. “I’m learning from my students already.”

In some ways, Uysal’s work has always been a return—a long arc from southeastern Türkiye to the classrooms of Cambridge, from handmade rugs to digital mapping, from silence to speech. What began as a fight for an education has evolved into a philosophy of design that treats the planet as a living archive of memory and meaning. It is a perspective shaped as much by experience as by scholarship: the child who watched the seasons shift over an ancient landscape has become the scholar urging designers and planners to move with, not against, the rhythms of our planet.

Uysal’s story is less about success than about continuity—the enduring thread between land and learning, between the resilience of her Kurdish ancestors and the generative curiosity that defines her work today. “Every step,” she says, “is another way of listening—to people, to place, and to the Earth itself.”

Practicing Growth in a Finite World: An Ethics Of Patience and Pragmatism

Two themes—pragmatism and time—dominated last week’s Practicing Growth in a Finite World, a Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) panel presented as this year’s Carl E. Sapers Ethics in Practice Lecture and hosted by the GSD Practice Forum. Four experts—one philosopher and three built‑environment practitioners—approached the question of growth and sustainability in a resource‑constrained world from distinct vantage points. Their conversation, urgent yet mindful of the incremental pace of change, surfaced ethical frameworks for 21st‑century practice and examined how designers can work within today’s constraints to make room for future transformation.

Architects, planners, and designers face a constellation of ethical quandaries. Moderator Elizabeth Bowie Christoforetti, assistant professor in practice of architecture and chair of the GSD Practice Forum, set the stage with a sobering fact: buildings produce more than 40 percent of global carbon emissions. In an age of relentless urban growth, that number captures a central paradox. Political and professional pressures demand speed—the rapid delivery of affordable housing and public infrastructure—even as every new square foot adds to the planet’s carbon and waste loads. Technology can scale these efforts , magnifying both progress and harm—harm potentially so devastating that some commentators argue for a moratorium on new construction. Beneath it all runs a familiar tension: the push to maximize returns for clients versus the desire to create culturally meaningful work. As Christoforetti observed, “the context for 21st-century design is thus a pressure cooker of external complexities.”

The urgency of the moment was brought into focus by philosopher Mathias Risse —Berthold Beitz Professor in Human Rights, Global Affairs, and Philosophy and director of the Carr-Ryan Center for Human Rights at the Harvard Kennedy School. “Architecture and design are at an ethical crossroads,” he argued. The only ethically responsible path forward, Risse suggested, is to become a “pragmatic moral agent”—someone who “works within existing systems to minimize environmental impact, promote sustainable practices, and gradually shift attitudes toward building and consumption.” The practical and temporal dimensions he outlined echoed through the reflections of the remaining three panelists.

Jane Amidon (MLA ’95), professor of landscape architecture and director of the Urban Landscape Program at Northeastern University, examined how practitioners navigate questions of public space, nature, and human experience. She pointed to large-scale, dynamic projects, such as those involving ecological rehabilitation and landscape maturation, that rely on “small tools of incremental change” and sustained advocacy—efforts that unfold over decades. Working closely with communities, she noted, designers can help shift expectations and foster acceptance of new approaches, such as coastal landscape projects in recent years that make room for rising water rather than trying, futilely, to hold it back.

“I’m interested in how design can work within the systems of today and catalyze or allow for the possibility of a different tomorrow,” said Neeraj Bhatia, advocating a similar forward-looking approach. A professor at the California College of the Arts and founder of THE OPEN WORKSHOP , a design-research practice, Bhatia discussed Lots Will Tear Us Apart, a recent collaboration with Spiegel Aihara Workshop that proposes a new housing typology for San Francisco. The project reimagines community living by rejecting conventional property division and private ownership, instead using prefabricated cores and flexible configurations to promote alternative living arrangements that allow for higher density and communal land. “The project asks how the architect can preconfigure the conditions for more collectivity, sharing, and social resilience,” Bhatia explained. “It offers the possibility of other ways of life that can slowly reconfigure the system over time.”

Dr. Dana Cuff , a professor at UCLA, concluded the discussion by focusing on spatial justice and the work she leads through cityLAB , a UCLA-based non-profit research and design center. “In every form of practice,” Cuff observed, “there are ways of doing work that step outside a capitalist model, whether it’s pro bono efforts in a traditional practice or … an organization dedicated to something like affordable housing.” One of cityLAB’s first breakthroughs was its research into the feasibility of accessory dwelling units (ADUs) in California, which helped shape 2016 legislation that opened the door for an estimated 8.1 million ADUs statewide. Building on that momentum, Cuff and her team turned their attention to small vacant lots throughout Los Angeles, launching Small Lots, Big Impact in spring 2025—a design competition aimed at prototyping and promoting housing on underused parcels. As she remarked in response to an audience question, “Capitalism is the air we breathe. Once you accept that, you have to ask yourself: what can you do to shift the trajectory, even slightly, and open up new possibilities?”

Cuff’s reflection echoed a point made earlier in the evening by Sarah Whiting, dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture at the GSD, who opened the event by emphasizing design schools’ ethical responsibilities—to their students, the profession, and humanity. “If we want our students to advance the world, making it more beautiful, more just, more ecological, and more durable, we need to work with them to envision what practices can enable that,” Whiting said. “As we push the envelope of building envelopes, facades, structures, materials, forms, and programs, we need to push the envelope of practice itself.”

In the end, Practicing Growth in a Finite World revealed less a crisis than a recalibration. The panelists’ insights traced an ethics of patience and pragmatism—an acknowledgment that meaningful change in the built environment unfolds not only through grand gestures, but through persistant, systemic work. In confronting the limits of growth, they offered a hopeful reminder: that design’s true power lies not only in what it creates, but in how it reimagines the conditions for collective progress.

GSD Students Curate Archives on Black Designers and Landscapes

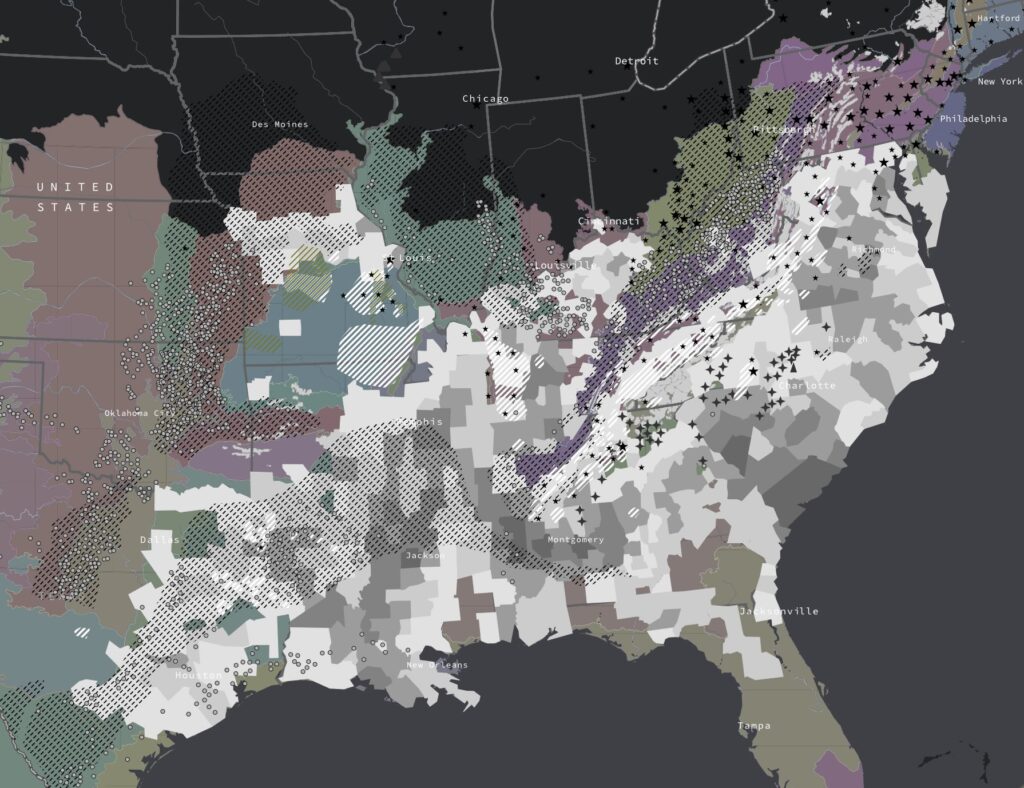

This summer, Graduate School of Design (GSD) students Michael Anthony Bryan II (MLA ’26) and Tyler White (MDes, MUP ’26) traveled a humid path through rural Virginia and Texas to document Black landscapes, delving into historic records, oral histories, and the built environment for clues to the past. They were among the GSD students whose research was supported by the Penny White Project Fund.

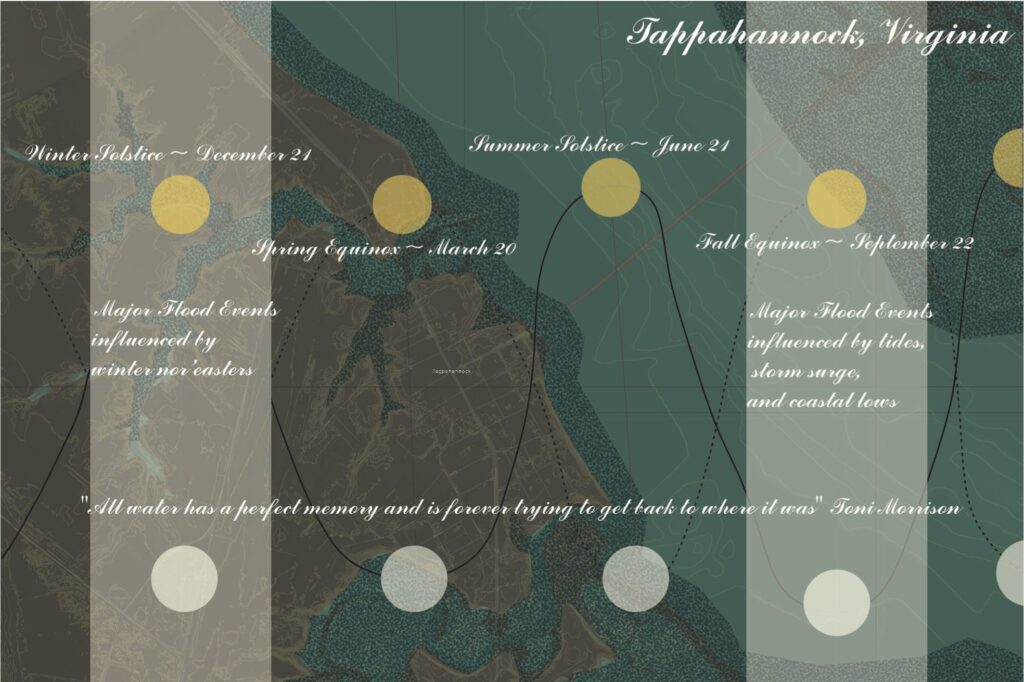

The funding allowed White and Bryan to join a three-day trip organized by Rutgers’ Black Ecologies Lab in Richmond and Tappahonnack, Virginia, to study, as the Lab explains, “Indigenous (Rappahannock) and Afro-Virginian practices of place, land, and water stewardship…,” and then, employing similar research methods, they traveled through Texas on their own. They chronicled their journey with audio recordings and photography, creating an archive of images and maps to document sites where Black people designed and built landscapes.

Their work is now on display at the GSD in the student-run Quotes Gallery

, alongside documentation of other student projects supported by the Penny White Project Fund.

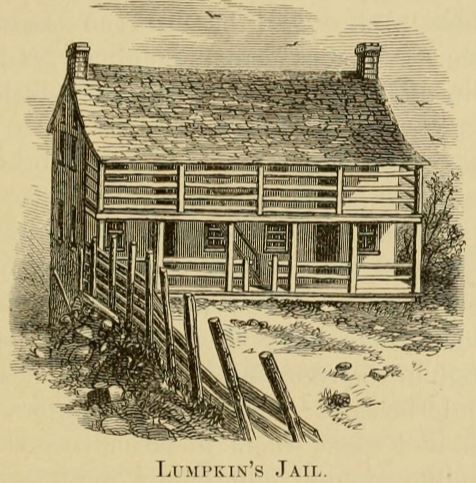

In Virginia, the group observed Indigenous canoe-making and visited the place where the Lumpkin Slave Jail once stood. A highway overpass runs above a few fallen cement blocks on the grassy soil, a small sign marking the spot that’s now part of the Richmond Slave Trail. Nearby, over the remainder of the site, a perfectly manicured grassy field stretches vacant and quiet. In the 19th century, enslaved people were imprisoned at the jail before their sale.

“I was left with this profound feeling,” said Bryan, “of the fact that there are all these spaces where our ancestors lived, and their lives have been glossed over. The only evidence of their existence is one or two stones on the site, or a marker that acknowledges that people have died here. There are so many stories there that will never be uncovered, never be told.”

Bryan and White encountered more traces of such stories when they continued their journey in Texas, a state they chose for its relatively well-preserved freedmen’s towns, settlements established in the 19th century by formerly enslaved people. They note that they witnessed “a staircase to nothing in Houston’s Freedmen’s Town ,” as well as “mounds poking up out of the earth in a cemetery behind a Best Inn in Galveston, and blocked access all along the rockiest most industrial parts of the Rappahannock River…”

Upon their return, they made a series of maps that mark the places they visited, creating connections to other sites around Virginia and Texas. They also compiled an annotated almanac of archival photographs and news stories of Black peoples’ lives and experiences. The pair explain that this research is grounded in the interdisciplinary fields of Black geographies

and Black ecologies

, the latter of which “explores the historical and contemporary relationships between Black people, land, and the environment,”[1]

and rose out of courses they took at the Graduate School of Design (GSD). Sarah Zwede’s “Cotton Kingdom, Now,” for example, revisited Frederick Law Olmsted’s 1852 journey through the American South, and Thaisa Way’s “History of Landscape Architecture,” examined the cultural and historical significance of gardens and landscapes.

White noted that his perspective shifted as he traveled and read about enslavement in the context of David Silkenat’s Scars on the Land

. “I learned so much about slaves being involved in mining—lead and iron ore mining,” said White, “and how often slaves were being hired out for work. In urban spaces, so many slaves were doing industrial activities alongside people who were not enslaved, troubling, for me, the idea of class and labor relations.”

The landscapes they visited held evidence of the labor that shaped the spaces, but, while some were well-maintained, others had been neglected. “We went to a spot in Galveston, Texas, and found a hidden cemetery that was surrounded on all sides by motels, at the bottom of a flood basin,” said Bryan. “The mosquitoes and bugs were eating us alive.” He turned to Toni Morrison’s writing about water forever returning to its source, integrating her words into the map of flood zones in Texas to ask how we can “care for spaces that are also continuously under threat with climate change and rising waters,” and manage urban systems that are “falling under their own weight” with an influx of “stormwater, flooding, and infrastructure issues.” With that environmental degradation, he explains, we lose these sites of memory that hold evidence of past lives and their design contributions.

In addition to traveling to to document Black architecture, White and Bryan have also worked at the GSD to recognize and document the school’s Black designers. In February, 2025, they co-curated “Architecture in Black,

” an event during which attendees examined various archival documents and publications in the Special Collections Reading Room at the GSD’s Frances Loeb Library. The event, part of a series of “archives parties” hosted by special collections curator Inés Zalduendo, was curated in collaboration with the African American Student Union (AASU), and supported in part by the GSD’s Racial Equity and Anti-Racism Fund.

“Architecture in Black,” named after Darrell Fields’ book , which “demonstrate[es] the ‘black vernacular’ in contemporary architectural theory,” examined materials that, Bryan and White explain, speak to “how Black GSD Alumni have conceptualized, devised, and produced architecture from and within Blackness.” They highlighted objects such as Fields’ 1993 publication of “A Black Manifesto” in the Harvard journal APPENDIX: Culture/Theory/Praxis , Audrey Soodoo Raphael’s GSD thesis “From Kemet to Harlem and back: cultural survivals and transformations;” Nathaniel Quincy Belcher’s thesis “Taking a Riff;” and Sean Anderson and Mabel O. Wilson’s book Reconstructions: architecture and Blackness in America.

White explained that one of the goals for their trip to the South was to “bring attention and activity back to these spaces.” The archives party served a similar purpose, bringing together students, faculty, and staff to discuss historic Black designers at the GSD. As they wrap up their penultimate semester at the GSD this fall, Bryan and White plan to continue to recognize the people whose design sensibilities and labor created our contemporary expression of architecture, landscape architecture, and urban design and planning.

[1]

“Historian J.T. Roane Explores Black Ecologies,” emerald faith rutledge, JSTOR Daily, February 14, 2024. https://daily.jstor.org/historian-j-t-roane-explores-black-ecologies/

The GSD’s History of Teaching Equitable Development in Allston

Harvard is not only an urban campus, but it is a campus in a congested city . . . . The acquisition of new land implies a careful study, not only of prices, taxation, and location of parcels, but also of size and shape of those parcels in terms of their future use. The programming and needs of new buildings and a rough calculation of the size and type can be of great help in an intelligent policy for Harvard’s future purchases.

—Jose Lluís Sert, 1957, as quoted in “Campus Harvard + Allston,” by Richard Marshall and Linda Haar

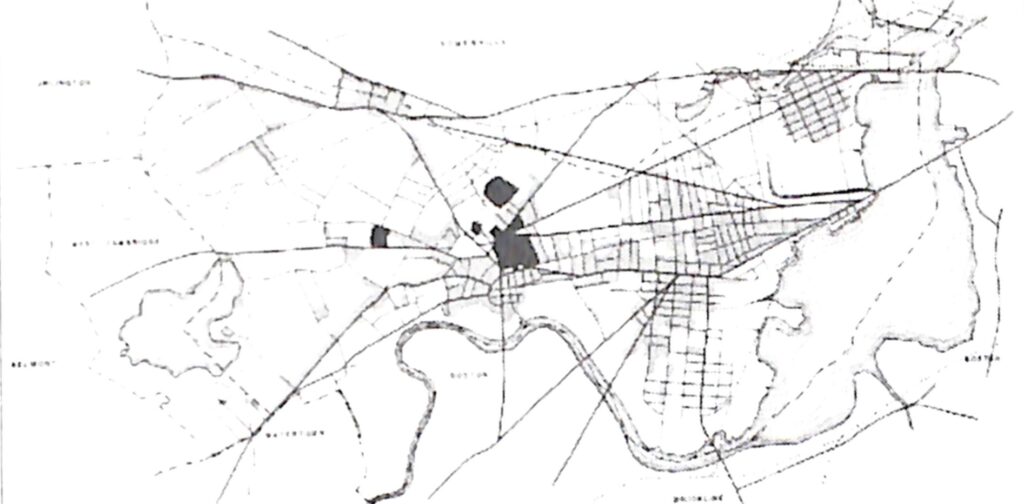

Faculty and students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) have studied the prospect of developing a campus in Allston since the 1990s, after it was revealed that Harvard had been buying land in the neighborhood. But even before that, GSD studios such as “The Beacon Yards, New Urban Structure,” taught in 1987 by Associate Professor Jonathan S. Lane, considered the neighborhood as a site with rich potential for future equitable development that benefits the Allston community.

At the initiation of a developer who approached the GSD and sponsored the studio, Lane looked at 200 acres in Allston, “including the Allston Landing truck depot, a section of the Mass. Turnpike and its Toll Plaza, as well as considerable frontage on the Charles River.” The studio aimed to create connections between the site and the Charles River, allowing access to green space for residents and Boston University students, who were hemmed in by the transportation depots.

In considering how the site might be developed, the studio studied comparable examples of projects that transformed transportation depots into livable neighborhoods, including Philadelphia’s Penn Center and 30th Street Station, Boston’s Prudential Center over the old Boston and Albany Yards, and Pittsburgh’s “Golden Triangle.” Lane notes that some examples are more successful than others. For example, he cautions that the “inhumane” scale of the Prudential Center in Boston should be avoided.

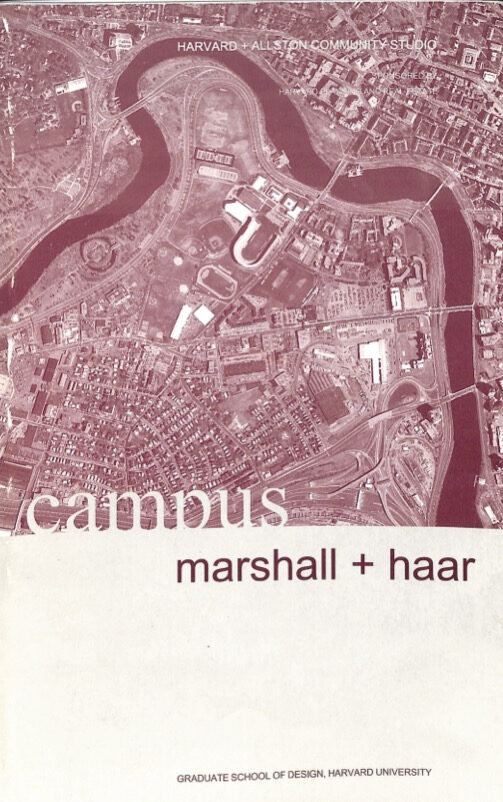

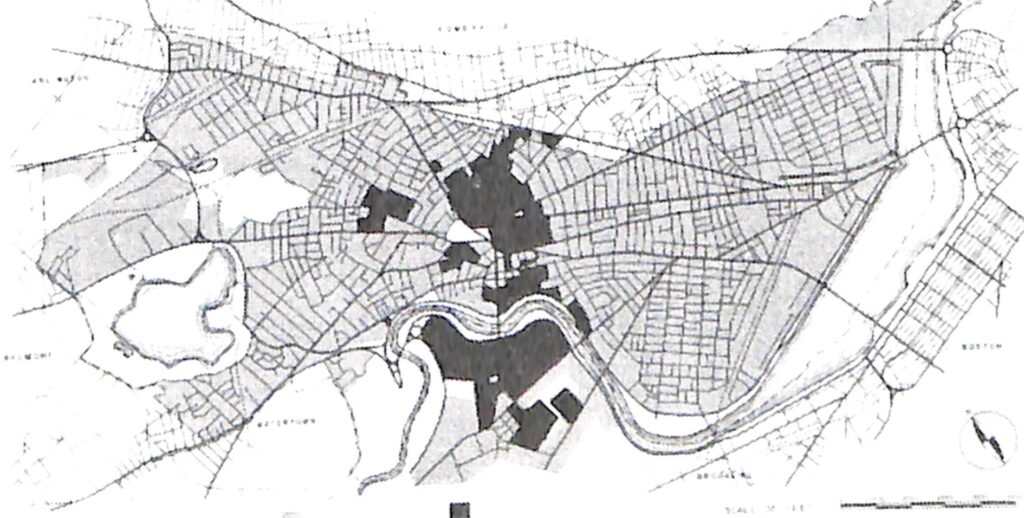

On the heels of the news about Harvard’s purchase of Allston lands, in 1999, GSD instructors Richard Marshall and Linda Haar co-taught “Campus Harvard + Allston,” which recounted the history of development in Allston and offered a range of proposals for the campus. They note that as early as 1925, Harvard founded its campus in Allston, when Henry Lee Higginson proposed to President Eliot “developing the ‘unsavory stretch of brackish mud flats and marsh.’” A competition was held in 1924 to select the architect for the new Graduate School of Business Administration. McKim, Mead, and White—one of the nation’s leading architectural firms at the time—was selected, and Frederick Law Olmsted’s firm designed the landscape.

The 1999 studio asked students to consider three concerns in Allston: “Housing, the redevelopment of Western Avenue, and the expansion of the Campus.” As students looked at each aspect of development, they would need to consider how Harvard would interact with its neighbors, for example, in ensuring sufficient housing for residents. Today, housing remains a pressing issue, and a housing complex is a significant portion of the Enterprise Research Campus that has recently opened in the neighborhood.

In 2002, Alex Krieger, Professor in Practice of Urban Design, Emeritus, taught a course on the development of Allston’s campus, in which one of the students proposed a “science hub” for the neighborhood. The group spent the semester grappling with concerns around how the university would interface with the community. Several years later, in 2008, GSD students gathered in another Allston studio, this one led by instructor Jonathan Levi , to focus on student and community housing in the neighborhood. Looking back to Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell, who changed Harvard’s conception of student housing in the early 20th century, Levi noted that the “attempt was to democratize the benefits of living on campus.” After consulting with Allston residents and community members, students in the studio designed housing for Harvard students in Allston.

The subject arose again in 2018, when Shaun Donovan and David Gamble co-taught “A Campus in a City—A City in a Campus: Harvard and Allston,” an urban planning and design studio that interwove “architecture, urban design, planning and landscape architecture to transform and grow a new neighborhood in Allston at the intersection of campus and city.” Exploring what Harvard’s “100 acres will become,” the studio emphasized the importance of equitable access to the neighborhood’s “innovation economy.”

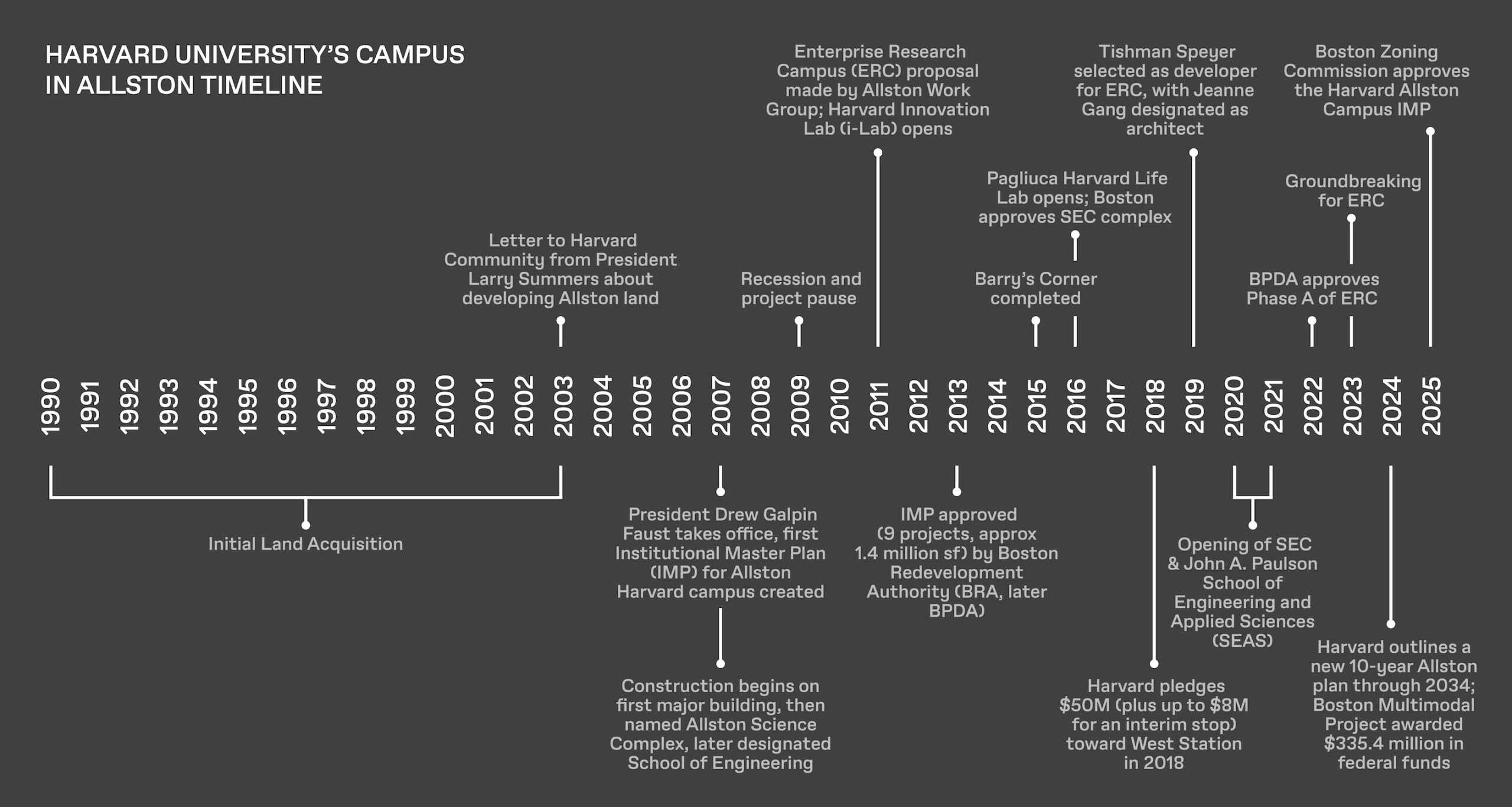

GSD students were also part of the conversation around Allston’s development in the 2017 competition for an art installation at The Grove, and in a series of public events such as a 2020 conversation between Marika E. Reuling and Thomas Glynn, moderated by Stephen Gray, with Martin Zogran, Courtney Sharpe, and Rustom Cowasjee. Reuling is the Harvard’s Managing Director for Allston Initiatives, Glynn is the Chief Executive Officer of the Harvard Allston Land Company, and Rustom Cowasjee (MAUD ’82), is a part of Tishman Speyer, the developer for the Enterprise Research Campus. Most recently, in 2025, Martin Bucksbaum Professor in Practice of Urban Planning and Design Joan Busquets taught “Harvard Campus and the Changing Nature of the University,” focusing on both Cambridge and Allston. As construction progresses in Allston today on the ERC campus, GSD students will continue to help innovate and design in partnership with Allston residents.

Alex Krieger on the History of Harvard’s Allston Enterprise Research Campus

For nearly 50 years, Alex Krieger, professor in practice of urban design, emeritus, taught at the Graduate School of Design (GSD). For about half of those years, he was committed to helping Harvard in the development of the Allston campus , serving on work groups, task forces, and design review committees focused on the project. First working with Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers and his administration in the early 2000s, Krieger helped to initiate a master planning process that, through various iterations over the years, ushered in the Allston campus. The first phase of the Enterprise Research Campus is now nearing completion.

In addition to his scholarship, he’s well-known for his “iconic tour” of Boston that focuses on how the city, which was originally settled on an island, created land to accommodate its growth. He dedicated his career to the study of urbanism, with books including City on a Hill: Urban Idealism in America from the Puritans to the Present (2019), Urban Design (with William Saunders, 2009), and Mapping Boston (with David Cobb and Amy Turner, 1999).

Here, he recounts the history of the Allston campus and how he’s witnessed—and helped shape—its evolution into the landscape we see today, with the opening of the David Rubenstein Treehouse conference center , the “front door to the Enterprise Research Campus.”

How did the idea for a campus expansion originate?

Upon assuming the presidency, and with the then-recent public acknowledgment by the university that it had been acquiring land in Allston, Larry Summers announced the need for an ambitious master plan to prepare Harvard for its next decades of growth. He would reveal his own ambition that Allston would enable Harvard to establish “the Silicon Valley of the East,” given the university’s leadership in the sciences, and its researchers’ role in the mapping of the human genome that had just been completed by the International Human Genome Project. At the president’s direction, an international search for architects and planners ensued.