Jeremy Ficca on Biogenic Materials: Where High Tech and Low Tech Meet

By the early 1900s, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, had emerged as an industrial powerhouse, due in large part to its prodigious steel production. More than a century later, the city has refashioned itself as a center for innovation. It is thus fitting that Jeremy Ficca (MArch II ’00), an associate professor and incoming Associate Head of Design Fundamentals in the School of Architecture at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), has concentrated his research on biogenic building materials. Made from rapidly renewable resources such as plants and fungi, biogenic materials offer a sustainable alternative to standard materials such as steel and concrete, requiring less energy for sourcing and construction, and even assisting with carbon sequestration. This semester, as a design critic in the Department of Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), Ficca is teaching an option studio called “Material Embodiment: Logics for Post-Carbon Architectures” in which biogenic materials—and geogenic materials, which are sourced from the earth’s crust—feature prominently.

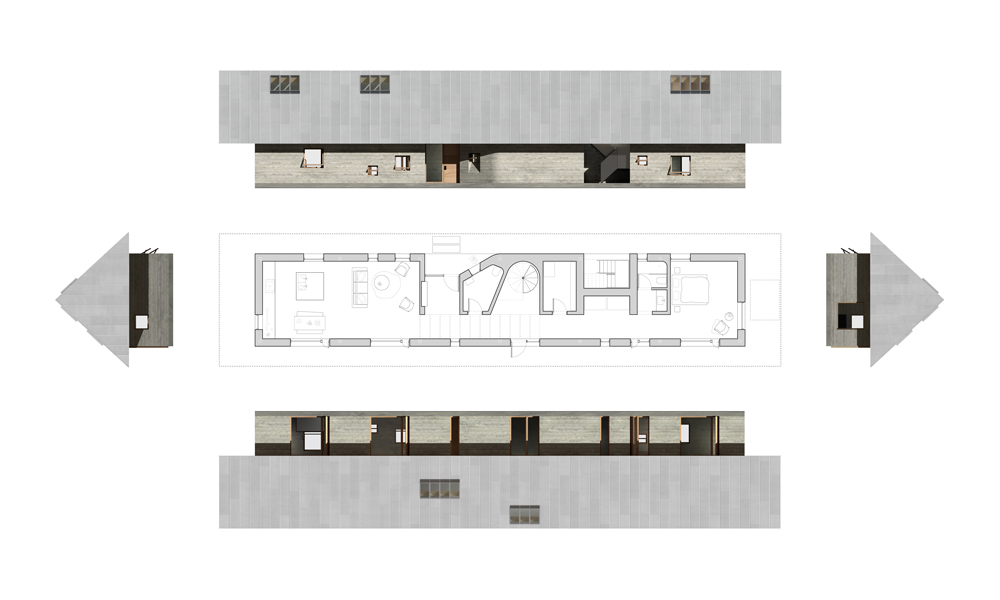

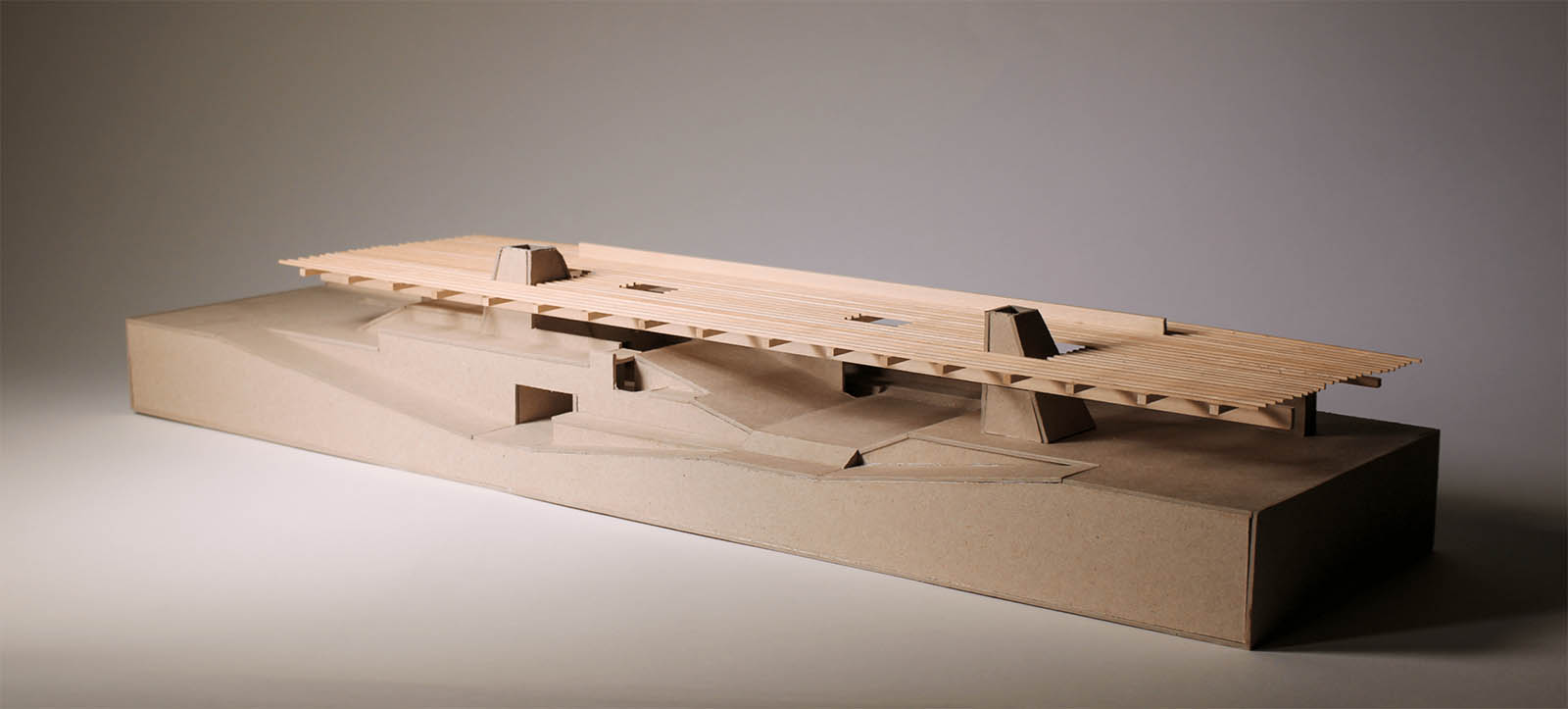

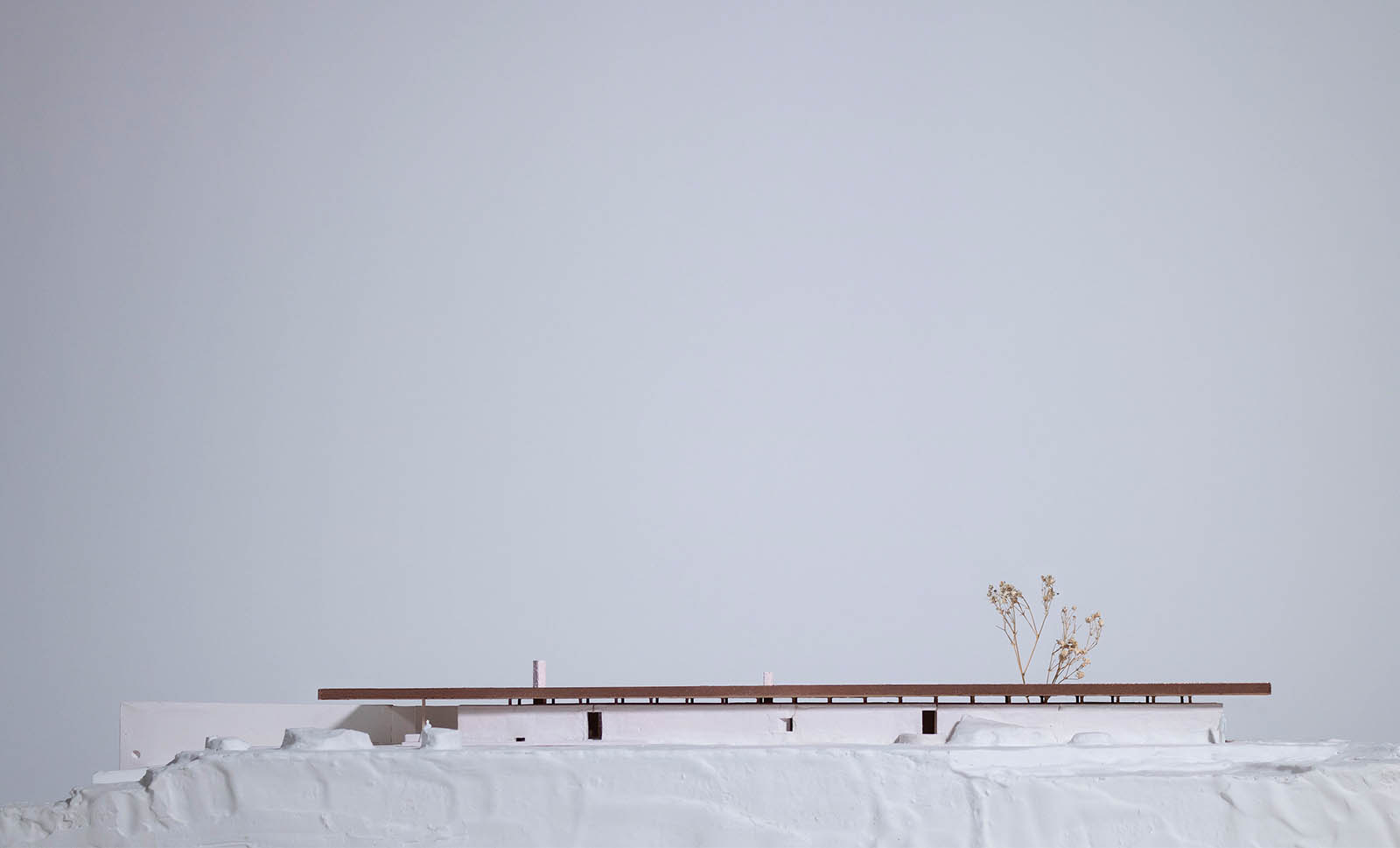

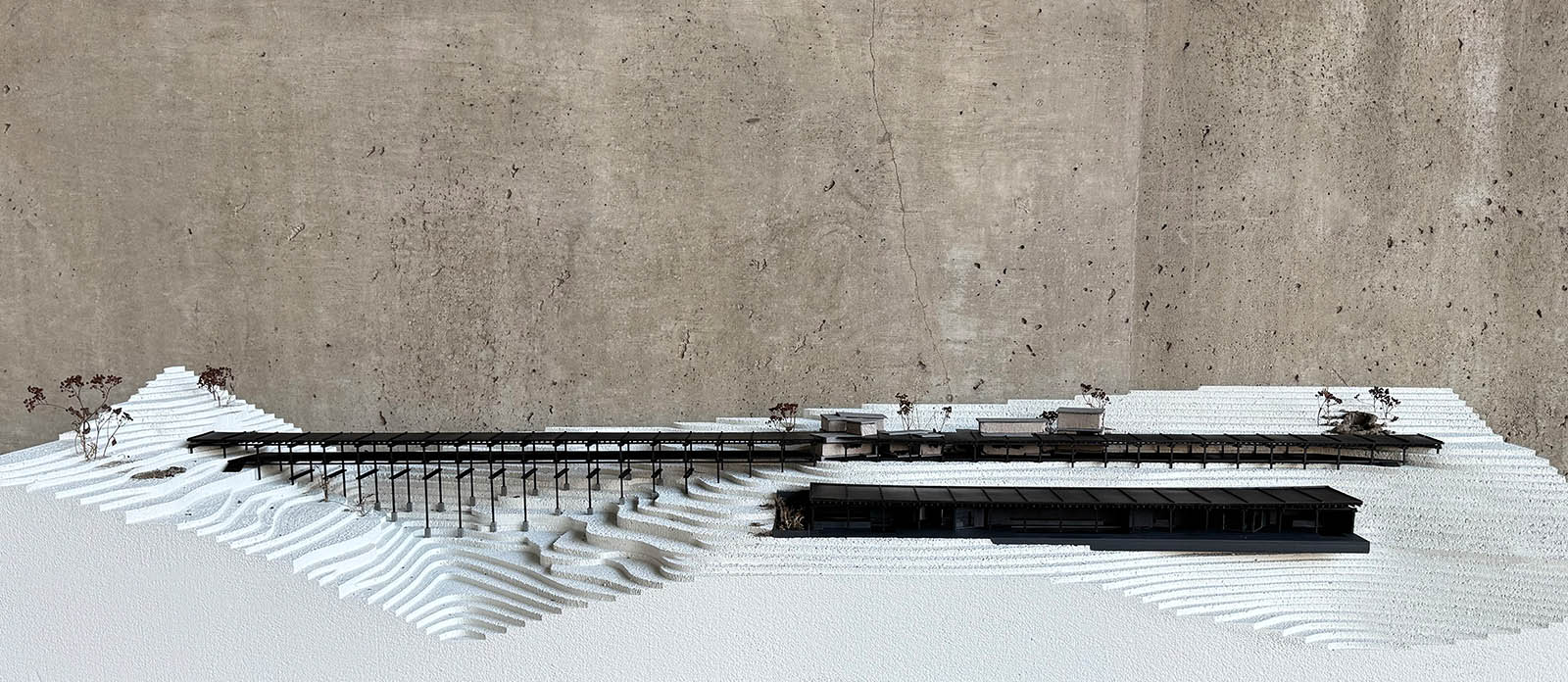

With respect to buildings, Ficca explains, we tend to think about energy and carbon in two ways. The first and more conventional outlook involves increasing energy efficiency for elements like heating, cooling, and lighting, often through technological means. The second relates to how and with what materials buildings are constructed, along with the externalities that accompany these design decisions, such as their impacts on human labor and greenhouse gas emissions. This more holistic approach underlies the “Material Embodiment” studio, in which students explore bio- and geogenic materials (such as hemp, straw, and earth) to design a hybrid workforce-training and research facility on an old river-front industrial site in Pittsburgh’s Hazelwood Green. The studio asks the students to rethink the material composition of a building as well as their designs’ broader implications on material sourcing, labor, construction technology, and maintenance.

Ficca recently spoke with Krista Sykes about bio- and geogenic materials, his own research, and the urgency for change within the architectural discipline.

How did you become interested in biogenic materials?

My teaching and design research focus on the intersections of materiality, technology, and architecture. While this initially operated within the field of computational methods of design and fabrication, material affordances were a common thread. As one who teaches courses and studios that focus on the materialization of architectural intent, I contend with the impact of building on our planet’s ecosystems through the carbon intensive and extractive nature of construction. Like many of us, I spent time during the pandemic looking inward. The writings of ecological economist Tim Jackson were an important influence on my understanding of post-growth and the imperative to transition to a more resilient economy and society. Around the same time, I was asked to reconceive a core material and construction course for graduate students in CMU’s Master of Architecture program. Doing so provided an opportunity to fundamentally rethink this content in relation to climate change and resilience. The questions that began to arise through the development of the course and subsequent discussions with students highlighted the inadequacy of simply trying to achieve greater and greater efficiency in building performance rather than exploring how the building’s material makeup can substantially reduce energy and carbon expenditures.

We are at a precarious moment. There is broad consensus that our climate crisis requires fundamental recalibration of the acts of building to address the negative externalities of the process. There is no single solution to this immense challenge. Responses will be quite different depending upon local circumstances. I am interested in how material practices can address questions of embodied carbon and energy and how these practices might open space for design imagination and architectural expression. This is a technical problem but also a deeply cultural question.

In the North American context, the most universal biogenic construction material is wood. But there is a remarkably rich range of harvested and grown materials alongside wood, including bio-resins, mycelium, and hemp, to mention but a few. Some biogenic materials belong to longstanding traditions of building, while others emerged through rigorous research and development processes. My current work focuses on industrial hemp and lime, often referred to as hempcrete. While the combination of these materials to construct walls dates back more than thirty years, it is somewhat analogous with straw and cob techniques that have much longer histories.

You mentioned that some of the biogenic materials being explored in the studio connect to longstanding building traditions. Could you say more about the materials you have in mind?

Some of the students this semester are exploring loam (earth and clay) construction. These are practices with long histories that were largely passed over because they were incompatible with industrialized building techniques. There is remarkable work underway by architects like Roger Boltshauser and Martin Rauch that seek to situate these methods within the technological circumstances of our time. This is in part a process of reconnecting with practices that were perhaps deemed to be pre-modern, inefficient, or even primitive. But this renewed interest does not result from nostalgia or a desire to return to pre-modern vernacular techniques. Rauch’s development of prefabricated insulated rammed earth blocks is a response to the challenges of scale, labor, and construction costs. As their work is demonstrating, adoption of these techniques will require automation to address their labor intensiveness. Additionally, there is research underway at the Gramazio Kohler ETH research group developing robotic deposition of clay to yield monolithic architectural elements. It is a fascinating melding of high and low tech, of high precision and lower-resolution architecture. I find these calibrations, frictions, and occasional contradictions to be both exciting and a source of opportunity, prompting questions about the cultural connections between how we conceive of our environments and the materials with which we build.

How did your research come to focus on hemp and lime?

In December 2018 the United States passed the 2018 Farm Bill, removing hemp with extremely low concentration of THC from the definition of marijuana in the Controlled Substances Act. Passage of the bill legalized the growth and processing of industrial hemp nationwide. As I researched industrial hemp, I was impressed by its remarkable attributes as a crop and its performance as a building material. Per acre, industrial hemp is one of the most effective CO2 to biomass crops.

The convergence of the farm bill and the performance capacity of hempcrete that was emerging through research in the EU pointed to opportunities for applications in the US. There is a track record of industrial hemp farming in the EU and UK with a few noteworthy examples of buildings that utilize the material. I was initially drawn to the labor-intensive nature of using hempcrete as a site-rammed material, and its potential to inform incremental, process-oriented approaches to construction within domestic architecture. I was interested in how a house might grow over time along with the harvesting and processing of material. This work, at the scale of the house, has transitioned into the design of discretized assemblies.

How does your work dovetail with the students’ pursuits throughout the semester?

The studio directs attention to one of the fundamental elements of architecture—the wall. We do so in part because many bio- and geogenic materials lend themselves to solid construction that relies upon accretion, processes of layering, compressing, and stacking. Materials like hempcrete and rammed earth require solidity and thickness to achieve thermal performance. But we also take on the topic of the architectural boundary because it reveals contemporary tendencies and desire. Principal among them is the legacy of modernism’s focus on lightness and thinness. The students are exploring spatial organizations and expressions that are informed and inspired by materials that require different processes of formation.

The students are developing proposals for a skilled workforce-training center located on a post-industrial site in Pittsburgh that was once a coke works and steel mill. It is a site with a long and complicated history of industrial growth, human labor, economic and environmental collapse, and regeneration. As I alluded to earlier, some of these materials are quite labor intensive. There are different attitudes to this topic. Some argue for greater human energy over embodied material energy and embrace the potential for the creation of new skills and jobs, while others point to automation to achieve scale and affordability. I am not advocating for one approach; rather, I’m interested in how the students’ positions on labor and technology inform their work. How might they calibrate architecture to production by humans and machines?

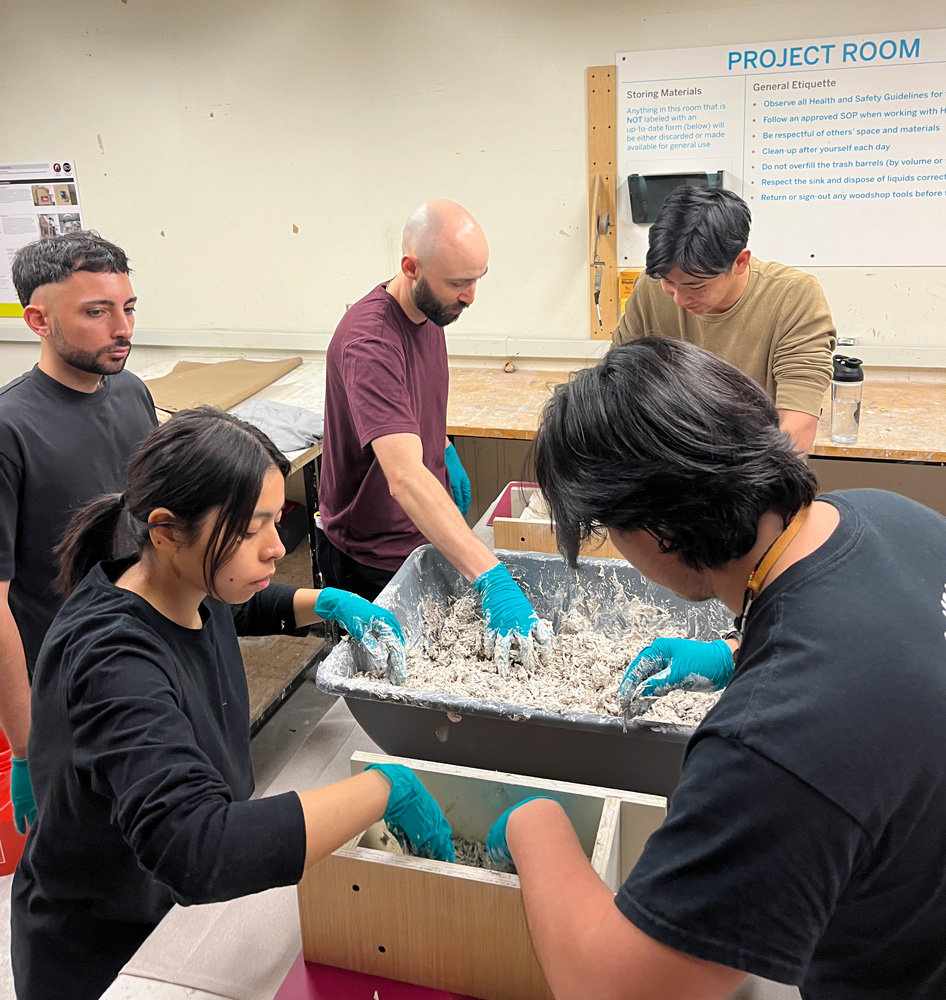

Very early in the semester we cast some hempcrete blocks. This experience allowed us to work directly with the material, understand the limits of its resolution, and appreciate the characteristics of a low-processed natural material. Hempcrete, like many bio- and geogenic materials, can be hard to control. It is inherently somewhat imprecise. This pushes back against the characteristics of most contemporary building materials, which tend to rely on high degrees of precision and predictability.

Another point of convergence between my research and the work undertaken in the studio this semester is the topic of durability. Most buildings are constructed to be highly durable, to withstand weather and time. And there are many good reasons for this; buildings are expensive to construct and maintain. Some of the materials we have been working with challenge that approach in that they can be understood as weak, or to require different forms of maintenance and repair. A lot of the ways in which one engages contemporary construction is to try to minimize those conditions in a building. Over the history of many cultures, there have been remarkable practices of maintenance and care, some that also have functioned as cultural acts in society. So, when we build with materials that are low in energy, low in carbon, as great as they might sound, there are certain tradeoffs, and perhaps one of the tradeoffs is the fact that they might require different forms of care and maintenance. Rather than this being perceived as a problem to be overcome, might there be an opportunity here? Might this challenge the way we think about a building’s lifespan and open new ways of considering the traces of time and the finishing of a building?

As low energy, low carbon, sustainable alternatives to conventional materials, bio- and geogenic materials offer exciting possibilities. It seems that reframing potential problems associated with these materials as disciplinary opportunities renders them even more promising.

I agree. I want to be careful not to oversimplify or generalize. Making even a small building is a complex endeavor that relies on hundreds of materials with a wide range of embodied carbon and energy. These questions need to be considered holistically to weigh tradeoffs. The material practices we’ve discussed raise fundamental questions about the status quo of construction and its impact on environmental degradation; in doing so they open space for imagination. I find this territory, coupled with the various frictions and complications, to be quite useful for students to operate within.

*All images by Jeremy Ficca, unless otherwise noted.

The Plural Forms of African Landscape Architecture

“Landscape is a way of beholding that is inclusive of nature and culture, of people and environment,” said Jala Makhzoumi. “It is anchored, it is situated, it is contextualized.” An Iraqi landscape architect based in Beirut, Makhzoumi offered these reflections to encourage expansive thinking about her discipline as part of a two-day conference hosted by the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) and the Department of African and African American Studies. The international participants in “African Landscape Architectures: Alternative Futures for the Field” explored what it would mean for the practice of landscape architecture to be anchored in the continent’s diverse cultures, ecologies, and traditions.

Introducing the conference, organizer Gareth Doherty (DDes ’10), associate professor of Landscape Architecture at the GSD and affiliate of the Department of African and African American Studies, described the tremendous potential to foster landscape architecture as a discipline on the continent as well as the urgency of undertaking socially grounded, culturally relevant design practices there. Doherty was among the speakers who noted that Africa has the youngest population in the world, with approximately 70 percent of people in Sub-Saharan Africa under age 30. By 2050, Africa will be home to some 850 million young people. Such demographic projections underscore the need to create sustainable cities. As Thabo Lenneiye of the University of Pennsylvania observed in her presentation, “African cities and settlements are on the front lines of climate change,” not only threatened by the effects of warming, but also subject to a new, terrain-destroying scramble for the rare earth minerals critical to emerging “green” technologies. As climate change accelerates, designing for resiliency in Africa for Africans may be the most urgent task for landscape architects today.

Meeting these demands requires the broad perspective Makhzoumi offered, as well as the input of artists and philosophers, who were among the conference participants. Pointing to the conference title in his introductory talk, Doherty stressed the need for landscape architectures: “this ‘S’ is very important because it represents a plurality of forms of practice.” Such plurality was evident from the first panel discussion, which featured prominent GSD alumni of different generations. Returning to his alma mater for the first time in 50 years, Johan van Papendorp (MLA ’75) took stock of his career shaping the urban greenspaces of Cape Town, South Africa. Spanning from Table Mountain to the sea, the network of landscapes van Papendorp helped develop was inspired in part by the Boston’s iconic Emerald Necklace park system, created in the nineteenth century by Frederick Law Olmsted.

Exemplifying an alternate mode of practice, Arthur Adeya (MLA ’06) and Chelina Odbert (MUP ’07) discussed their work in the Kibera section of Nairobi, a dense, underserved slum whose needs run deeper than green space. Adeya and Odbert instead worked with members of the community to develop “productive public spaces” that offer verdant refuge but also facilities for social gatherings, economic workshops, and public health and education initiatives. While this vision of landscape architecture as community infrastructure developed in Kibera, Adeya, Odbert, and their collaborators at the Kounkuey Design Initiative (KDI) have also applied their methodology to public spaces and community development projects as far away as inland Southern California. “This is really Africa exporting landscape architecture,” said Adeya, reflecting on how their experiences in Kibera have translated to international projects.

Discussions throughout the conference focused on the need to reverse the colonial logic by which Western models had long been imposed onto African settings. What would a new landscape architecture, rooted in Africa, look like? Doherty spent a recent sabbatical year traveling the continent and visiting academic institutions with landscape architecture departments. The profession itself is in a nascent stage, with only eight of 54 African nations currently home to professional associations of landscape architects. Though increasing, the number of landscape architecture programs at African universities also remains relatively small. Doherty built relationships with many of these institutions. In addition to encouraging virtual participation at the live-streamed conference, he has invited students in Africa to participate in his GSD class as guest speakers.

Still, as speakers on the “Pedagogies” panel emphasized, the growth of academic programs also needs to be matched by the development of an African-centric curriculum. Finzi Saidi of the University of Johannesburg confronted this question as he described his work with Unit 15x at his university’s Graduate School of Architecture. He and his colleagues research “landscapes in post-colonial African societies to propose culturally appropriate designs” reflecting the dynamic conditions of contemporary Africa. Yet within nations grappling with the legacies of colonialism, what might be the basis for such designs? Doherty recalled a workshop that included Saidi and Sechaba Maape of University of the Witwatersrand. The latter relayed his students’ complaints that they were being taught to design cities for white people. Maape responded with a challenge: “Show me what a city for Black people is like.” The answers Maape presented made reference to ancient African ritual spaces, proposing answers to contemporary ecological problems while invoking deeply ingrained spiritual practices that connected people to the land.

Indeed, the theme of spirituality in landscape design ran through the conference, invoked in the opening session by Jacob K. Olupona, Hugh K. Foster Professor of African and African American Studies and Professor of African Religious Traditions, and chair of the Department of African and African American Studies. Olupona noted that the conference built upon a 2019 gathering at the GSD, also organized by Doherty, focused on the tradition of sacred groves, which are prevalent in West Africa and also maintained by descendants of Africans in Brazil. Forests stewarded by people for the purpose of spiritual expression, sacred groves offer one touchstone for reimagining African landscape architecture in general. The sacred felt viscerally present in the conference from the start as Princess Adedoyin Talabi Faniyi of the Osun Sacred Grove in Osogbo, Nigeria, offered a Yoruba blessing for the proceedings. She also spoke later that night as part of the International Womxn’s Day Keynote event alongside Tarna Klitzner, a designer based in Cape Town, and moderator Zoe Marks, director of the Harvard Center for African Studies. The Princess movingly described how the forests, rivers, and terrain that she oversees “acknowledge the interconnectedness of nature and spirituality.”

This spiritual connection to nature can also serve as the basis for a sharper critique of contemporary political economy and historical power imbalances. Olatunji Adejumo of the University of Lagos argued that Western Enlightenment philosophy, imported to Africa, had informed colonial uses of the land. Adejumo drew a contrast between “Spiritscapes,” defined by a biocentric philosophy and local knowledge, and the extractive logic underpinning the “Resourcescapes” that Africa had become in the colonial imagination. Turning to African traditions and precedents for her own work championing regenerative agriculture and environmental stewardship in the Lake Victoria region, Lenneiye invoked figures like Thomas Sankara, who planted 10.5 million trees in Burkina Faso in the 1980s; Wangari Mathaai, who encouraged women to learn forestry skills in Kenya; and Zephanaiah Phiri, a water harvesting advocate in Zimbabwe. These historical precedents suggest a rich basis for sustainable landscape practices in Africa in the future, what Lenneiye described as “locally relevant, community informed adaptation plans that integrate African environmental philosophies and practices.”

While looking ahead to a future when these philosophies and practices might thrive throughout the continent, “African Landscape Architectures” also featured inspiring examples from the present. Joe Christa Giraso of Mass Design Group, based in Boston and Kigali, Rwanda, provided an overview of the meticulous research that went into the designed landscape for the Ellen DeGeneres Campus of the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund. Through this scientifically informed landscape design, the campus’s stunning natural setting also became an active research site for reforestation techniques in Rwanda.

As the scholars and practitioners at the conference made clear, landscape architecture is a growing discipline within Africa, but also a porous one. Makhzoumi, who is also acting president of the International Federation of Landscape Architects, the Middle East Region, argued, “I don’t think landscape is the domain of Landscape Architects.” The alternative futures for the field charted in the conference suggest a new kind of hybridity in line with Makhzoumi’s flexible notion. Through the discussions, it became possible to imagine landscapes in Africa guided by spiritual leaders, artists, agriculture specialists, planners, philosophers, and various communities in partnership with an emerging generation of professionals.

Igniting Radical Imagination

“Think about someone who harmed you deeply. What would it take for you to sit down across from them, and ask them, Why? What supports would you need?”

This is one of the prompts that Deanna Van Buren, architect, activist, and director of Designing Justice + Designing Spaces (DJDS), asked the audience to consider during her talk, “Designing Abolition,” on Tuesday, March 4, at the Graduate School of Design (GSD).

After her presentation, Van Buren was joined in conversation by her collaborator Andrea James , an activist, lawyer, and community organizer whose goal is to end incarceration for women and girls.

Van Buren designs systems of care that replace the carceral system. Her organization’s buildings focus on community-building and restorative and transformative justice—spaces where people can have healing conversations to resolve conflict, get support finding jobs and childcare, grow and prepare healthy foods, and work with community members to support the neighborhood.

Diverting people out of the prison system and into systems of care requires collaborating across industries. For example, Van Buren worked with lawyers, prosecutors, asylees, and others in Syracuse, New York, supporting The Center for Justice Innovation to open the Near Westside Peacemaking Project , the country’s “first center for Native American peacemaking practices in a non-Native community.” Now, instead of sending people to prison, judges can send them here for support within the neighborhood. The center features a Women’s Reentry Lounge, Circle Event and Art Space, Youth Zone, and Welcome Lobby. People have come to congregate at the center, gardening together in the yard, and using it for quinceañeras and engagement parties. This, says Van Buren, moves people from “incarceration to community cohesion. Prisons don’t keep people safe; this keeps people safe.”

In California, the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights launched Restore Oakland the nation’s first center for restorative justice and restorative economics, which prompted Van Buren to create the real estate side of DJDS to acquire properties in ways that best serve communities. DJDS also supported Allied Media Projects to develop the LOVE Building in Detroit, Michigan, a commercial space with offices for nonprofits, which inspired DJDS to pursue the Grand River at 14th Parcel Assembly, with additional facilities for family support, youth activities, food justice initiatives, workforce development programs, education and literacy training, health and wellness services, and arts and culture groups. DJDS also designed the Common Justice Headquarters in New York, which serves victims of violent felonies and diverts people from prisons, as well as mobile refuge rooms to house formerly incarcerated people, exhibited at the Smithsonian Design Triennial under the title “The Architecture of Re-Entry.”

Restorative justice, transformative justice, and trauma-informed design are at the foundation of Van Buren’s practice, which she developed in part during her 2013 Loeb Fellowship , after working as an architect for 12 years. At the GSD, she described how she thinks about designing a room where people can have difficult conversations—the core of restorative justice, whose premise is that harm can be resolved without punishment, and that with the right supports in place, people can thrive. “A core part of what it means to be human,” Van Buren explained, “is conflict and resolution. We avoid it. We don’t have skills. We don’t practice it.” Rather than sending someone to jail for attempted murder, for example, the two parties can sit in a room and talk to one another. Designing a space like this requires a deep understanding of trauma and how it works at the physiological level. “If you’re going to go into a conversation that’s very traumatizing…you need an environment that’s going to help you with that interaction.” She described how limited views, access to daylight, art that reflects our identities, and the ability to move the chair away from the other person are just a few of the design elements that create felt safety, which calms the nervous system.

During her tenure as a Loeb Fellow, Van Buren created her own multidisciplinary course of study to develop skills she knew she’d need. “I rode my bike over the snow in Cambridge to take classes at different schools across Harvard. I took Marshall Ganz’s public narratives class at the Kennedy School, and planning with Michael Hooper at the GSD. I took a class on research methods for designers at MIT.” She enrolled in a course on analyzing visual data at MIT, and a workshop at Lesley University on Circle Keeping, a restorative justice practice that brings into conversation people who were part of an incident that caused harm. Her process was intuitive and interdisciplinary, in pursuit of “mak[ing] space for restorative justice.”

Van Buren proposed that, as we face a complicated era that some call “the great turning,” shifting from profit-focused industry to supports for people and the environment, we have the opportunity to choose how we intervene. Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s definition of abolition provided a framework for her talk and the ensuing conversation with James, which focused in large part on how to close prisons in New England as a model for nationwide prison closures and alternative systems. “Abolition’s goal,” writes Gilmore, “is to change how we interact with each other and the planet by putting people before profits, welfare before warfare, and life over death.”

Van Buren suggested that we might consider three key questions: “What do we need to dismantle? What is the world we want to build? What skills will be required?” In the US, she said, “we have a lot to dismantle.” We’re facing “centuries of gross structural inequity in every community in this country and around the world,” which is evident in tree and food deserts, rural and tribal lands disinvestment, the US’ 1969 Freeway Act, and “co-located toxic land use,” among other challenges. Prisons in the US were built on “punishment, torture, and enslavement,” which “has to be unbuilt.” And, although people are attempting to open new prisons, more than 400 have been closed in the US in the last fifteen years, most of which now sit vacant.

“Designers are world-builders,” Van Buren said. “I cannot think of anything more important for designers to do,” she said, “than to ignite radical imagination.”

She described how the Atlanta City Detention Center, a jail that housed thousands of people, could be transformed into a Center for Equity, a food ecosystem, or community space, with potential for education and housing opportunities. The secure lobbies could be reinvented as “super lobbies where people can come in and be navigated to care-based resources.” We could “reimagine the justice core.” She illustrated this point with a map of the city’s justice system—the courthouse, police station, schools—and emphasized the importance of choosing an easily accessible site for the restorative justice center that is close to the justice core.

Instead of turning to punishments when people hurt one another, transformative justice views the harm as “a breach of relationship.” The people harmed need to “have their needs met” while the person who hurt them “makes amends.” No one, therefore, is being taken from their community, and returned to it later with the additional layers of trauma inflicted by prisons. Transformative justice helps people “heal by examining underlying issues, such as racism.”

New projects by DJDS include participation in a collaborative initiative to determine how to develop the newly closed MCI-Concord, which was the oldest operating prison in the nation, founded in 1878. Van Buren is also working with James to advocate closing women’s prisons in New England. Their focus is the last women’s prison in Massachusetts. With only 135 incarcerated women in Framingham, James argues that it would be relatively simple to close, and would mark the end of women’s prisons in the state, although the current governor is investing to construct a new women’s prison. Van Buren offers alternative models to prisons. Transformative justice spaces like the ones she created in California and Michigan divert people from prisons into systems of care, where they can find the support they need to remain in their communities.

“We have already created an exit plan for every single one of those women [in the Framingham prison]. We are uniquely poised in Massachusetts,” said James, “to close the women’s prison and create what different looks like, to become a model for the rest of the country.”

She and Van Buren continue to push to end incarceration for women and girls throughout the country, and to implement the abolitionism defined by Ruth Wilson Gilmore. In order to create new systems, Van Buren argues that we need to “develop the ability to hold complexity,” undertaking interdisciplinary collaborations to solve complex problems. To best prepare for the world that awaits them, Van Buren encouraged current GSD students to enroll in courses across Harvard’s schools in pursuit of their interests, noting that the MDes program provides a model for the kind of interdisciplinary study that helped her achieve her goals as a designer for transformative justice.

Peter Chermayeff on Taking Risks and Embracing Collaboration

For his first architectural commission, Peter Chermayeff landed a big fish: Boston’s New England Aquarium. It was 1962; Chermayeff was 26 years old, had earned his master of architecture degree from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) a mere six months prior, and didn’t yet have a license to practice architecture. He and his partners had just created Cambridge Seven Associates, a multidisciplinary collaborative firm of architects and graphic designers that would soon gain international prominence for a range of work, from small exhibitions to large mixed-use complexes.

More than six decades later, speaking about his early success, Chermayeff humbly observes: “I have a certain willingness to take risks, I suppose. And I have surrounded myself with first-rate collaborators.” Of course, his continued achievement stems from more than a penchant for risk-taking and multidisciplinary collaboration. A world-renowned authority on aquariums, responsible for high-profile projects such as the National Aquarium (1981) in Baltimore and the Oceanarium (1998) in Lisbon. Yet, the self-described “ambivalent architect” nearly didn’t become an architect at all. He had settled on filmmaking when a well-timed risk and a collaborative enterprise changed his mind.

The son of Russian-born modern architect Serge Chermayeff , Peter immigrated with his family to the United States from England in 1940 at the age of four. He and his brother Ivan (four years Peter’s senior) spent the next year with family friends—Walter and Ise Gropius in Lincoln, Massachusetts—while their parents traversed the country in search of an American outpost. Over the following decade and a half, as the father assumed a series of teaching positions (including stints in California, New York, and Chicago), the sons graduated in succession from Philips Academy at Andover. In 1953, the same year that Serge assumed leadership of GSD’s first-year program, Peter entered Harvard College with his sights trained on architecture. He majored in Architectural Sciences, which allowed him to commence graduate work after only three years of collegiate studies. Thus, in the fall of 1956, Peter entered the GSD.

Chermayeff immensely enjoyed his first and fourth years of his architectural studies, taught respectively by his father (“a hell of a good teacher”) and Dean Josep Lluís Sert (“a master and superb teacher.”) “The school was filled with energy and talent,” Chermayeff recalls. “I was intrigued by the power of the community, the quality of my classmates, and the fun we had in exchanging ideas. I was learning as much from my fellow students as I was from the faculty.”

Yet, even while enjoying his time at the GSD, Chermayeff wasn’t convinced that an architectural career was right for him. He had spent a summer in New York working for his brother Ivan, who had recently launched a graphic design firm with Tom Geismar. (Over the years, Chermayeff & Geismar would craft a plethora of highly recognizable logos including those for NBC, Mobil, PBS, and Chase Bank.) Another summer, Chermayeff worked with the Italian sculptor Costantino Nivola in his studio on Long Island as the artist created a large cast-concrete bas relief for an insurance company building in Hartford. As Chermayeff neared the end of his schooling, these endeavors prompted him to think less about architecture as a career and “more so about the visual arts, filmmaking in particular.”

During his final year at the GSD, Chermayeff had achieved unexpected success with a 15-minute experimental film. Titled Orange and Blue, the unnarrated film depicts two rubber balls, one orange and one blue, as they bounce from a bucolic wooded landscape into a junkyard strewn with the detritus of modern life. Taking a liking to the production, a film distributor paired Chermayeff’s short with Ingmar Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly as the Swedish feature toured the United States. Chermayeff found the unanticipated accolade to be “funny, ridiculous, but also wonderful.” What’s more, says Chermayeff, “I realized that, in the course of doing the film, I’d had more fun than I’d had doing anything with architecture.” So, upon graduation from the GSD, in 1962, a year when US officials were urging families to build fall-out shelters, Chermayeff set out to make another film—this time an informative documentary on the effects of nuclear weapons.

Six months later, as Chermayeff was immersed in raising funds and producing the documentary, his friend Paul Dietrich (MArch ’56) suggested they start a collaborative firm that would combine architecture, urban design, graphic design, and industrial design. Chermayeff declined; “Paul,” he explained, “I’m off in another direction. I’m making films.” Yet, the idea had been planted in Chermayeff’s mind.

The following week, Chermayeff made a bold move. He traveled to the Franklin Park Zoo in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood and, without an appointment, approached zoo director Walter Stone. “He must have thought I was crazy. I told him that I thought his zoo was dreadful,” Chermayeff recalls, “and that it could be rethought, reimagined, replanned, and changed for the better if he would allow us.” Stone was intrigued, agreeing to attend a slide presentation in Chermayeff’s Cambridge studio on how the as-yet-unnamed firm would revitalize his zoo. Impressed by their ideas but without funding to hire them himself, Stone introduced Chermayeff to the person in charge of developing a new aquarium in Boston. After a successful meeting, the fledgling firm was included on the project’s short list of architects, and an interview followed. Ultimately, Chermayeff and colleagues were selected to design the New England Aquarium—a lynchpin in the renewal of downtown Boston’. “And that,” says Chermayeff, “is how we started Cambridge Seven.”

As the name implies, seven partners initially comprised the collaborative venture: in addition to Chermayeff, four architects—Louis Bakanowsky (MArch ’61), Alden Christie (MArch ’61), Paul Dietrich (MArch ’56), Terry Rankine—and graphic designers Ivan Chermayeff and Tom Geismar, who simultaneously maintained their New York practice. They were all relatively young (Dietrich, in his mid-30s, was the elder stateman of the group). Yet the men had secured a major project, “an adventure in itself,” recalls Chermayeff, “because it involved reimagining and reinventing a building type—an urban aquarium, a place of encountering nature.” For Chermayeff, though, the New England Aquarium commission took on additional significance: “it meant that I could in fact find my way in this field because the project called for interwoven exhibition design and graphics and would address the content of things as much as the form of the envelope or the planning of the surroundings. It became, for me, place-making with a purpose, driven by content and context.” Opened in 1969, the Boston aquarium played a key role in transforming the city’s waterfront into a vibrant public locale. It also led to more aquarium commissions around the globe.

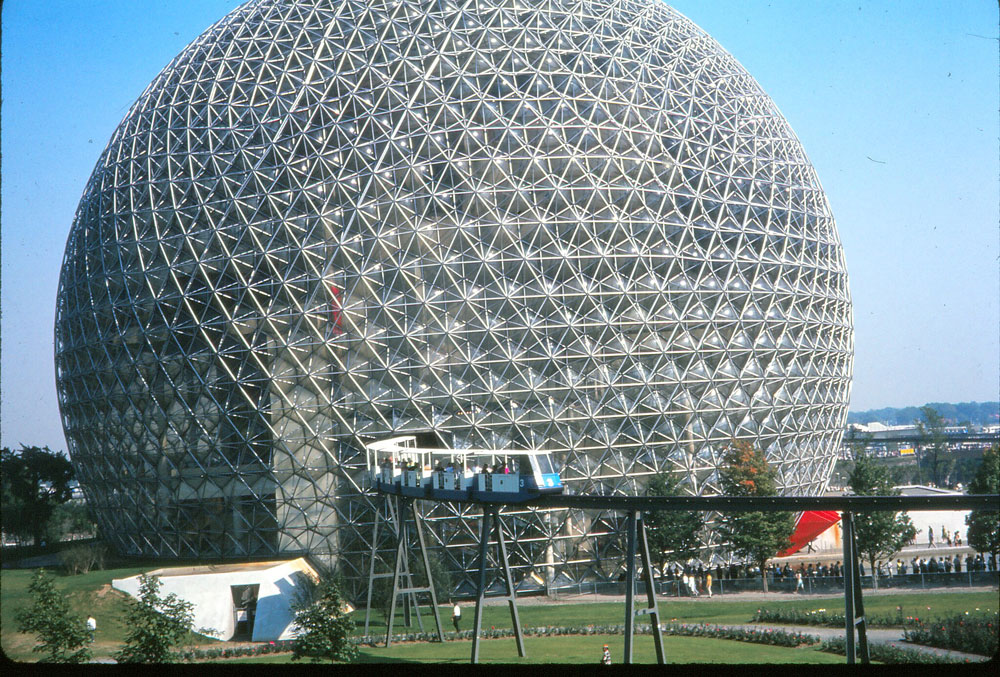

Even before the New England Aquarium’s completion, though, Cambridge Seven acquired two noteworthy projects—”not from the aquarium particularly,” Chermayeff notes, “but from the notion of the firm as a multidisciplinary collaboration.” The first arrived in 1964 when Jack Masey, design director for the United States Information Agency, invited Cambridge Seven to spearhead the US Pavilion for Expo ’67 in Montreal . Chermayeff and the others worked with Buckminster Fuller to make a transparent bubble, a geodesic dome as a three-quarter sphere 250 feet in diameter, which Fuller’s team engineered. Cambridge Seven designed the interior, which consisted of staggered platforms, described by Bakanowsky as “lily pads,” joined by escalators and stairs. Exhibits showcased items from a NASA lunar landing module and oversized works of contemporary art to Raggedy Ann dolls and mouse traps—all products of American creativity and ingenuity. An elevated monorail further animated the pavilion, bisecting the spherical space at the equator as it transported Expo visitors throughout the fairgrounds.

The other prominent multidisciplinary project Cambridge Seven tackled in the mid-1960s involved environmental design for the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) transit system. As Chermayeff notes, “We made some basic changes that had to do with the experience of the user, the people who use the system, riding the trains or the buses, walking through the stations. We developed guidelines and standards and, above all, a system of graphics and identity that unified the different subway stations and gave clarity to where you were and where you were going.” These changes included rebranding the transit system as the “T,” an idea borrowed from Stockholm, Sweden. “We concluded that the ‘T’ would work as a symbol for a lot of very good reasons. Intuitively, if you see the letter T, you can think of transportation, travel, transit, tube. . . so many words that conjure the notion of what it’s all about,” Chermayeff says. Geismar painstakingly created the black-and-white “T” logo, still ever present throughout the Boston region.

Likewise, a version of the “T”’s minimalist spider map remains in use today, coherently depicting individual locations within a larger, unified system. As Chermayeff explains, they color coded the subway lines, providing each line with a geographically derived identity. Thus, the former Harvard–Ashmont Line was renamed the Red Line, referencing Harvard’s signature color. The track running to Boston Harbor and northeast along the sea became the Blue Line, while the Green Line branched toward Olmstead’s Emerald Necklace southwest of Boston. “And Orange . . . well, I just didn’t know what else to do,” Chermayeff confesses. “It was a fourth color, and it made sense to combine with the others!”

Above ground, the colors simplified the user experience, signaling the stations’ affiliations. “As you walk down the street, if you see green and orange, you know that this station takes you to both Green and Orange Line trains. This means that the whole city, the skeleton of the city, becomes more legible,” Chermayeff notes. “Looking back on it,” he concludes with a grin, “in terms of the impact on millions of people over time, I think what we did there was pretty terrific.” That this overarching scheme for the MBTA endures today, nearly sixty years later, suggests that Chermayeff is indeed correct.

Moving into the 1970s, Cambridge Seven continued to garner attention, completing an array of work including museums, educational buildings, and mixed-use complexes, eventually winning the American Institute of Architecture’s prestigious Firm of the Year award in 1993. Chermayeff became known internationally as the foremost aquarium architect, leading significant projects throughout North America, Europe, and Asia. He also continued to make films, including the eleven-part, non-narrated Silent Safari series for Encyclopedia Brittanica that depicts rhinoceroses, lions, and other animals in their natural East African habitats. Chermayeff left Cambridge Seven in 1998 with two younger collaborators, Peter Sollogub and Bobby Poole, and he continues to practice design with Poole.

Throughout his career, Chermayeff, the “ambivalent architect,” has approached the built environment through a multidisciplinary lens, integrating design and visual culture to make useful, inviting, inspiring places for the public at large. Thinking about the profession today, he forecasts an even greater need for collaboration. “An architect is, almost by nature now, an expression of a collective will rather than an individual will,” Chermayeff asserts. “We learn from each other, and we learn by tackling and solving problems that matter. I like to think that in the next several years, we’ll find ways to address issues like housing and the environment more broadly, where instead of individualistic statements, design occurs through more bees building their bits of the hive, reinforcing each other to make urban places that are humane and rich.”

Craig Douglas Visualizes the Invisible, Designing with Air

In an exhibition at the Frances Loeb Library, Craig Douglas, assistant professor of Landscape Architecture, explores one of the elements we most often take for granted: the air we breathe. An unconscious process, breathing is the one thing we can’t go without for longer than a few moments. In “Digital Air” (through March 16), Douglas renders the invisible visible, with photographs of the more than one hundred people around the world who gathered air samples at his request, a collection of books that contextualize his theories for designing with air, images of artworks that have engaged with concepts of air as matter, and a video that layers Giambattista Nolli’s 1748 “La Pianta Grande di Roma” (“Map of Rome”) with Douglas’s map of the city’s “geometries of air.”

The exhibition, Douglas writes, “claims air as matter by digitally reconceptualizing it as a material that is both corporeal and technological,” and asks us to consider how air can inform our understanding of the past, as well as current health conditions and our environmental future. Most importantly, it helps us to envision air as a physical component of the designed world, with its own topographical forms and ever-changing systems, shedding light on a new framework for structures and landscapes.

Rachel May: You asked people at different locations to collect air samples in glass vials at the same moment. What was significant about the time when this collection occurred?

Craig Douglas: All the air in the vials was collected at the exact time of the December solstice, which in Cambridge was 4:20 AM. Here, we call it the winter solstice and it’s the shortest day of the year, but, obviously, in the Southern Hemisphere, it’s the summer solstice and the longest day. It was an interesting time to recognize—not so much a cultural event, but a cosmic one. It fit in nicely with the idea of air as a cosmic atmosphere.

I received air samples from nearly a hundred places around the globe taken at exactly the same time, partly to illustrate the differences across the world and what they might mean. How different are each of these places through the matter of air itself?

RM: When you’re measuring the samples, can you tell the temperature at which they were taken?

CD: I asked people to use their local apps to record data, including temperature, humidity, and air pressure, which they shared with me. I used a range of other websites to collect other data, which includes levels of carbon monoxide, PM2.5, PM10, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen dioxide, which are the more problematic matters.

RM: The contaminants.

CD: Yes, they describe back to us the health condition of the air. On the windows of the library, you see the collection of air samples. But also displayed on the windows are chemical symbols and formulas for what actually composes the air. These symbols give air another nomenclature, in another form of media.

RM: Is that part of your motivation to collect air samples, to measure the health of a system or place?

CD: It is. Air is invisible, and, therefore, it often escapes our consciousness. Our breathing is automatic. We don’t think about it. But, air sustains our lives. Air is the thing that we can’t go without for the least amount of time. Including the samples of air from all around the world in the exhibition describes back to us that, yes, air is invisible, but each sample actually contains very different substances. Air varies as a matter. It has a material composition that affects everything around us. So, then, how can we then think about air in architecture—a medium that we design with and through?

RM: Is this map derived from the collection?

CD: These images combined to form a world map, which is perhaps less distinguishable because what I’m mapping is all of the air qualities on December 22, the solstice. I’m mapping the global condition on that day. The colored sections move from pinks to blues, where conditions are hazardous. I’m trying to redescribe the earth through the architecture of air at this global scale.

The film presented in the exhibition focuses on the Piazza Minerva, in Rome, and how air movement informs the quality of the space. I simulate this air movement through a range of different criteria. Sometimes, the air is visualized as points, which might be defined as particles or smoke or haze. Sometimes, the air takes the form of threads or lines conveying speed and trajectory.

RM: Is there an existing technology that gathered this data, or did you create technology to collect it?

CD: We created them all. What you see in the background is the [Giambattista] Nolli map, a 1748 map of the city of Rome. It’s the first accurate mapping of the city. This was part of the impetus for my fellowship at the American Academy in Rome. I was looking at the conventional mapping of Rome and trying to understand the city in terms of a figure-ground relationship.

The map describes the built environment as figure (black) and ground (white)—the positive is black, the void is white. As such, it describes the white as uncomplicated, unproblematic, and devoid of our attention. I’m turning that around and suggesting that, in fact, it’s a very important space. My study looks at how air forms that space. This image gives us a new drawing, a new understanding of the composition of the city through the construct of air.

RM: The way the air moves is beautiful.

CD: If we go back to the front of the gallery, to look at precedents that have gone before, you’ll see I studied Hans Haake’s Condensation Cube (1963–1967). It’s a clear Plexiglas cube in a gallery inside of which is a contained amount of air and a very small amount of water. It’s not a static object. It’s always changing, based on the heat in the room, how many people are present, how much sunlight might fall onto it, or the air conditioning—it’s continually changing. Air is no longer just a natural and invisible thing, but we as humans are very much part of its making and its continued transformation.

There’s a range of other precedents, for example, Étienne-Jules Marey was fascinated with making the invisible visible with air tunnel tests and smoke, which we’re quite familiar with today because we understand that, for example, the way the wing of a plane works is with updraft, making the air move more more quickly over the top so that you get a vacuum that gives you lift. These things are well-known now, but this work was astounding at the time.

Returning to the film at the back, I’ve taken this idea of the figure/ ground of Nolli and used his map, that sometimes you see appear and disappear into the background in the film, to bring to bear another reading of the city through the matter of air, or the architecture of air. We see the perception of air in the city as an interconnected fluid space, rather than the Nolli map, which describes it as a static condition of positive and negative space.

RM: How does this influence how you think about design and the work you’re making now?

CD: Conceiving of air as matter sets the stage for design. How can we consider or approach the design of the city or of spaces— the network of spaces—by considering air? Does that mean, then, that the landscape needs to be operable? Do we move elements around continually throughout the year to direct air?

Or, does it mean considering vegetation? For example, plants lose their leaves in the winter, which has a very different effect on the airflow outside—as well as the fact that the trees are part of the filtering process. Happily for us, they generate oxygen as a byproduct.

We might reconsider the landscape of the city or the city as a landscape by thinking about air and engaging with it as an operable condition. For instance, in Boston, we have a prevailing wind from one direction in the summer and another direction in the winter. So, when you see the Nolli map videos, this first series comes from an easterly direction. The next chapter of the video shows us the northerly wind, the westerly wind, and the southerly wind, and how these conditions dramatically change.

Our cities are already 2 to 3 degrees Celsius warmer than the surrounding countryside. The composition of the urban fabric captures contaminants and hotter air that affect our lives. Part of what we’re trying to map here is: Where are those air flows quicker? Where are they slower? Where could contaminants potentially get caught and trapped? And then, how does that impact our living spaces? How does it impact how we engage in these spaces? How are these qualities also then permeating into the interiors of the buildings? You can easily make the connection between the outside and the inside space, as well.

RM: How are you integrating this into your work with students?

CD: Last fall, I ran an incredible seminar about exploring atmospheric encounters, visualizing the invisible. I asked each of the students to select one element of the air—humidity, temperature, radiation. We then built digital sensors called sentinels using Arduino technology to measure that particular quality.

I also asked the students to visualize that data in real time. They would receive a digital readout telling them, for example, how much radiation is in this space at this particular time. They were able to take that data and redraw the landscape as an airborne condition. This was quite wonderful because now people are thinking about the landscape, the space that we live in, as a process rather than a static form.

Last year, I also ran an option studio in which we looked at how to redesign with air. How does air have a cultural impact, a social impact? What conditions might we be address with that information? Students looked at specific air conditions in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and then designed with those conditions. There are specific cultural and political conditions that play out that that make many things unusual, so it offered an interesting case study by which to pursue this idea.

When the Client is a Nation

Inside the Peabody Museum on a windy October day, leaders of the Sac and Fox Nation peered into the eyes of their ancestor, William Jones , the second Indigenous person to graduate from Harvard, in 1901. Posed in a cap and gown, Jones’s black-and-white photographs sit under a glass case beside a pair of beaded moccasins.

“He’s almost as good-looking as I am,” Principal Chief Randle Carter joked with Robert Williamson. Carter and Williamson had traveled to Harvard from Oklahoma, where Jones was born in 1871 and the tribe is based today.

The Sac and Fox are one of 574 Native tribes who operate as nations within a nation; they have the right to self-governance and maintain their own political systems . Williamson and Carter were invited to Harvard by Eric Henson, a lecturer in Urban Planning and Design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and a longstanding member of the Harvard Project on Indigenous Governance and Development , which helps Indigenous nations worldwide strengthen their governance systems. Henson’s Fall 2024 GSD course, “Native Nations and Contemporary Land Use”, brought together GSD students with representatives of the Sac and Fox—along with the tribe’s collaborator, a professional hockey team—to help the tribes meet their goals to regain sovereignty over their ancestral lands in Illinois.

“With a focus on land use, landback initiatives, and economic development opportunities,” writes Henson, “the course provides in-depth, hands-on exposure to how Native people are addressing these issues today.” Landback initiatives have been underway since the colonial era but only became widely known as such in the last few years. Part of Native nations’ work towards claiming their sovereignty, landback focuses on a number of initiatives, including acquiring land that was stolen from them throughout the process of colonization.

“If you’re building something new, or designing a park,” said Henson, explaining the importance of learning Indigenous history at a design school, “you have these steps you are supposed to check off: Did we do this review? Did we look for artifacts or archaeological dig sites? I’d like to see a degree of understanding beyond that. It’s not just a box to check off. You’re talking about real people who are victims of genocide and war and outright theft of their traditional territory. Taking a few minutes talking to a tribal leader before starting a design might open your eyes to the place in which you’re doing that work.”

For example, he says, in Bendigo, a town north of Melbourne, Australia, town leaders collaborated with the Dja Dja Wurrung , the Indigenous community, to incorporate Native design elements, revitalizing the town and attracting more investors. Henson noted that there are Native design elements in many buildings in Bendigo, which offers a model for others to follow.

This semester, students are working with two Indigenous Nations. Henson, a Chickasaw citizen, draws from his deep contacts with tribes around the US who have requested to work with him and his classes. The course Henson teaches at the Kennedy School , Nation Building II/Native Americans in the Twenty-First Century, offers collaborations with Indigenous Nations and now serves as a companion to the course at the GSD, with projects carrying over from one to the other. The course at the Kennedy School is cross-listed with the GSD, the Faculty of Arts and Science, the Graduate School of Education, and the Chan School of Public Health.

“With more education around Indigenous history, culture, and design, there could be tremendous collaboration between designers and Indigenous nations,” Henson argued, “with Indigenous design elements incorporated. In addition, non-Native communities that neighbor tribal lands have great opportunities, if they want to embrace them and work with tribes.” Not least of which, Henson explained, is the tribes’ access to federal funding and their role as major employers, particularly in rural areas.

This mutually beneficial relationship is what Rahul Mehrotra hoped for when he suggested a Native-focused GSD course to Henson in 2020, when Mehrotra was chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design. Henson collaborated with Philip DeLoria and Daniel D’Oca to design an interdisciplinary GSD class they called “Land Loss, Reclamation, and Stewardship.”

“In the context of discussions at the GSD on diverse ways of understanding history, and in the context of climate change,” said Mehrotra, “learning from traditional practices is very important. The relationship that Native Americans have to the land, and to nature more broadly, is sensitive, beautiful, poetic, and empathetic—and incredibly intelligent.”

GSD students’ work impacts the lived environment around the world, Mehrotra explained, and with more education about Indigenous people and their history, design students’ sensibilities would invariably shift.

“I wanted the Indigenous studies course to have history, design, and practice components,” said Mehrotra, “so that students would have a sense of what they can learn from history and traditional practices as they intersect with design.”

This past fall in Henson’s course, GSD students Cayden Abu-Arja (MArch I / MUP ’27) and Neady Oduor (MDes ’26) opted to work with Carter and Williamson to design a program to help them regain their ancestral lands, which the tribe determined was one of their primary goals.

“Our traditional lands,” Williamson explained, “are not in Oklahoma.”

For 12,000 years, the two tribes, then known as Sauk (now Sac), the Yellow Earth People, and Meswaki (Fox), the Red Earth People inhabited the area around Quebec, Montreal, and eastern New York state, but were forced southwest by the Iroquois, and then further west by the French. The two tribes banded together and moved to Illinois, establishing their summer village in Saukenuk, today known as Rock Island, along the Mississippi River. There, they planted 800 acres of corn, vegetables, and fruit to feed the almost 5,000 people in the well-organized community.

Abu-Arja and Oduor quoted tribal leader Black Hawk’s autobiography, in which he describes his memories of that place: “It was our garden (like the white people have near their big villages) which supplied us with strawberries, gooseberries, plums, apples, and nuts of different kinds, and its waters supplied us with fine fish, being situated in the rapids of the river.” Black Hawk recalled spending his childhood summers on the island, surounded by family.

In 1804, colonists tricked the Sac and Fox chief into signing a treaty that gave the land to Illinois, forcing the tribe off their summer grounds to the west of the Mississippi. By 1832, with the Sac and Fox people starving, Black Hawk led the community back to Saukenuk to plant their traditional summer crops.

“After years of encroachments from the US government,” said Williamson, “this was Black Hawk saying, ‘I want to go home.’” Instead, said Williamson, the Illinois militia “slaughtered women, children, and older men” over the course of more than three months, in what colonists called the Black Hawk War. The Sac and Fox were subsequently pushed further west again, this time to Oklahoma, where they live today and continue to fight for access to their ancestral lands.

Landback Initiatives & Innovative Collaborations

At the beginning of January, another tribe, the Prairie Band Potawatomi , were approved by the Illinois State House to receive a land transfer of 1,400 acres, which makes up Shabbona Lake State Park, named for Chief Shab-eh-nay. The government sold the land illegally in 1849, violating a treaty the Prairie Band had signed 20 years earlier. The Potawatomi have agreed to continue allowing public access to the park, which will be maintained by the state.

Tribes across the US have undertaken landback initiatives in different ways, from acquiring the land through private purchase to lobbying for it from state lands or through estate planning. For the Sac and Fox, a Nation with about 4,000 members, the goal is to follow the lead of the Potawatomi to reestablish their footing back in Illinois around the site of Saukenuk village. Today, Illinois maintains Black Hawk Historic Site on the tribe’s ancestral lands, with a statue of the warrior, a small museum that describes Saukenuk, and a 100-acre nature preserve. Williamson noted that, like many other Indigenous US tribes, their leaders’ names have been used for streets, towns, professional sports teams, and even army helicopters. They deserve to have access to their ancestral lands.

Joining Carter and Williamson on their trip to Illinois were representatives from the Blackhawks Hockey team, whose CEO, Danny Wirtz, has invited the nation to collaborate in ways the Sac and Fox choose. While many Indigenous advocates have argued for professional sports teams to change their name, Wirtz suggests that the collaborative work he and his team are doing with the Sac and Fox requires more authentically engaging with one another. The tribe voted to work with the hockey team and is prioritizing economic development, strategic planning (including landback initiatives), and language preservation projects.

“Our partnership with Black Hawks’ tribe, the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma,” says Sara Guderyahn, the Chicago Blackhawk’s Executive Director, “is centered around education and cultural preservation with the goal of supporting the Nation’s priorities for sovereignty. To that end, we are excited and optimistic that this project is an important step to explore opportunities for the Nation to reconnect with their original homelands in Illinois.”

GSD students Abu-Arja and Oduor began their work with the Sac and Fox by learning about the tribe’s history, including their forced migration through the US, Black Hawk’s leadership, and the Nation’s ancestral lands. The group’s visit to the Peabody Museum with Carter and Williamson highlighted the Sac and Fox’s most famous members: anthropologist William Jones, whose photos and writings they viewed alongside the leaders at the museum and in the archives, and football player Jim Thorpe, who won two Olympic gold medals in 1912.

“When you look at the record books,” said Chief Carter, “Thorpe was not a citizen of the US. Before 1924, Indian people were not citizens of the United States. The record should say he was a citizen of the Sac and Fox Nation.”

Henson led the group to visit a site on Harvard’s campus that brings Thorpe’s legacy back to contemporary material culture. At what’s now Clover Food Lab , the ceiling tiles that depict the early twentieth-century Harvard football league pennant flags include the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. When Jim Thorpe led Carlisle to defeat Harvard in 1911, the Indian School was cut from the league; Harvard never played them again. The Indian Industrial school was part of the US government’s attempt to erase Indigenous culture through the forced removal of thousands of children from their homes and families, under the motto “kill the Indian, save the Man.” When the tiles were uncovered on Massachusetts Avenue, right across from Harvard’s gates, in a 2016 renovation , they restored to the record in Cambridge the story of Jim Thorpe at Carlisle, before he went on to win Olympic gold medals.

The group’s visit to the site was part of a tour Henson led, which was originally designed by Jordan Clark, Executive Director of the Harvard University Native American Program (HUNAP) and a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Aquinnah. The tour makes visible the Indigenous histories that are often missed all around us.

For example, Henson pointed out a plaque on the side of Matthews Hall, commemorating the history of Harvard’s Indian College— founded by missionaries in the 1640s—whose bricks were eventually dismantled to build other Harvard structures. Henson pointed to a spot on the lawn beside Matthews Hall, where a 1990s archeological dig revealed pieces of the press used to print the Eliot Bible, written in Algonquin (a language of Indigenous tribes), the first Bible printed in the US, now held at the Houghton Library . Henson noted the plaque on the president’s house that names the enslaved people who laboured there, and the rusty pump in the center of the yard, which marks the water source from which Massachusett and other Indigenous people were cut off when settlers claimed the site.

Making Indigenous histories visible, highlighting how their stories predate colonization by thousands of years, as well as how they are irrevocably intertwined with Harvard’s history, helps to make tangible the ethos of the land acknowledgment that the GSD wrote in collaboration with HUNAP and reads at the beginning of every public event.

Strategies to Educate the Public and Regain Access to Saukenuk

After learning the histories of Indigenous nations in the east and midwest, Abu-Arja and Oduor focused on designing a program centered on “co-management” of the Black Hawk State Historic Site, which they say the Sac and Fox Nation “sees…as a way to connect with their ancestral homeland…and pass on traditions (some of which were lost when they were removed from their land).” The team outlined three goals: 1) creating storytelling opportunities so that people understand the “social and cultural significance of the Black Hawk State Historic Site” to the Sac and Fox Nation, 2) developing revenue streams, and 3) increasing collaboration with Illinois state.

They defined 15 different activities, from collaborating with the Sac and Fox to develop new exhibits at the existing historic site museum, to building clan houses for cultural activities, hosting riverside storytelling sessions and ceremonies, creating a gift shop, and “tailoring [the tribe’s existing language programs] to young students who visit the site.” They note that the Nation can turn to existing protections, for example, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which would support co-managing the cemetery where Black Hawk’s children are buried but remain unnamed on signage that commemorates settlers. As precedent for managing burial grounds, they cite Minnesota’s Indian Mounds Regional Park, which was developed around the gravesites of several tribal nations to protect the mounds and share their people’s histories. By increasing the public’s knowledge of and engagement with the Sac and Fox Nation, as well as collaborating with the state government, the Sac and Fox’s case for landback will become more visible—and therefore, more viable.

At the end of the semester, Abu-Arja and Oduor presented their proposals to the Sac and Fox Nation, who are moving ahead with their plans to develop the programs in Illinois, which they hope will bring them one step closer in their two-hundred-year battle, starting with their ancestor Black Hawk, to regain their lands.

Landscape Architecture Students Explore Pioneering Climate Visualization Techniques to Inform Design

Droughts, floods, food shortages, species extinction—the impacts of climate change are physically tangible. Yet, the terms and data used to describe these predicted impacts often seem abstract. Richer visualization techniques offer great promise to communicate the consequences of climate change and thereby promote the adoption of strategies to preempt these effects. This semester at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), master of landscape architecture (MLA) students are exploring two such innovative modeling approaches: a framework for understanding spatial impacts of climate strategies over time, and a modern sand table that supports real-time simulations.

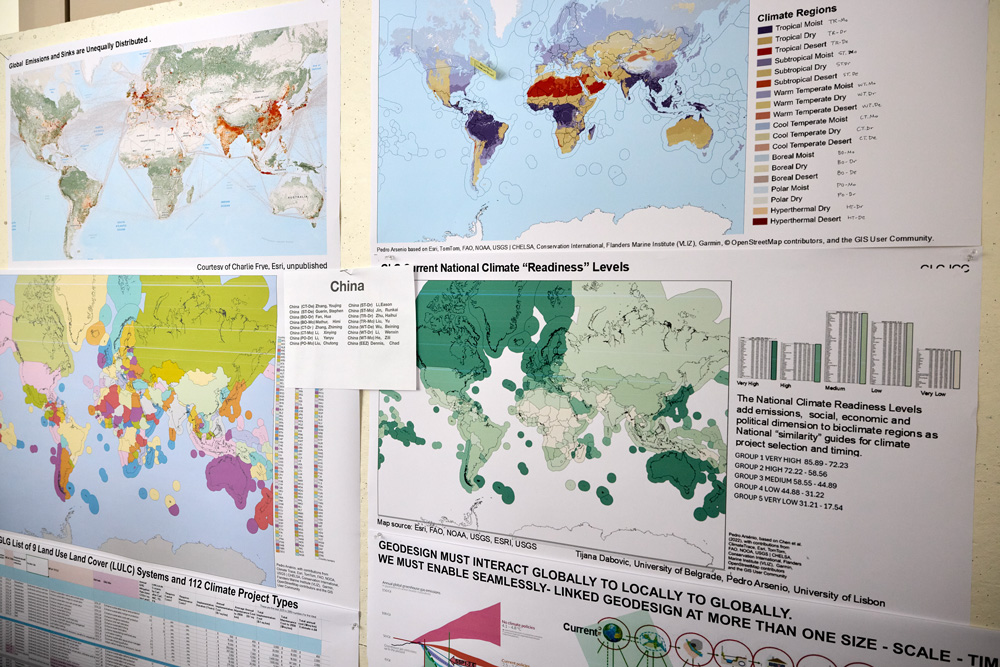

Since the 1960s, Carl Steinitz—Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Landscape Architecture and Planning Emeritus—has been contemplating land-use change as a designed process. As part of the Harvard Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis, Steinitz began using geographical information system (GIS) maps to evaluate the impacts on a given area of variables such as population growth and migration, financial influx, and environmental conservation. In the ensuing years, Steinitz developed a framework for “geodesign,” a term coined to describe design in a space linked to a geographic coordinate system with its accompanying specificities. Today the International Geodesign Collaboration (IGC), which Steinitz helped found, defines geodesign as “a collaborative approach [that] uses GIS-based analytic and design tools to explore alternative future scenarios in response to global problems.” When first exploring this problem five decades ago, Steinitz initiated his geodesign work with a two-square-mile geographical region; recently, he expanded this scope to the global scale.

In 2022, in conjunction with the company Esri —a global leader in GIS software, location intelligence, and digital mapping, cofounded by Jack Dangermond (MLA ’69)—Steinitz and additional collaborators began work on the ICG Global to Local to Global (GLG) Climate Mitigation Project, building the technology to facilitate geodesign for the purpose of climate change mitigation.1 Steinitz introduced the project to MLA Core IV students (those engaged in their final studio of the core sequence), characterizing mitigation as “a multi-jurisdiction, multi-scalar geodesign problem. Climate change,” he explained, “is a global existential phenomenon, and all nations must act in collaboration if climate mitigation is to succeed. Guided by climate science, this requires looking and thinking ahead in time, globally to locally to globally, and planning now to act now for the future of everyone.”

While multinational agreement and a global oversight of planning, negotiation, and implementation does not yet exist, Steinitz and colleagues view the GLG Climate Mitigation Project, a protocol to facilitate this process, as necessary infrastructure for future climate action. Building from a geodesign framework published in 2012, Steinitz has created tools to identify mitigation strategies to optimize impact by considering the date of initiation (for example, 2025, 2050, or 2080), execution and maintenance costs, alterations in climate (temperature and aridity), and additional variables across a span of decades. Focusing on changes in land use, the goal is to lower carbon emissions below zero, ideally (if perhaps improbably) returning atmospheric measurements to pre-Industrial Revolution levels. In short, the GLG Climate Mitigation Project offers a preview of, and guidance on how, mitigation-related decisions can affect our future.

Following his explanation of the project, Steinitz walked the MLA Core IV students through a tutorial on how to use it. This exercise served a double purpose, providing a test run for the tools themselves while preparing students for their upcoming semester-long studio “The Near Future City,” focused on Boston’s Charlestown neighborhood. Lorena Bello Gómez, GSD design critic in landscape architecture and lead instructor of the studio, sees the GLG Climate Mitigation Project as a climate action framework students can use to determine suitable mitigation strategies for the studio’s site. These include strategies such as enhanced wetland restoration, neighborhood energy retrofits, infrastructural recalibration, urban canopy growth, and sustainable wastewater management.

Charlestown sits within a warming climatic region that, in years to come, will face increasing challenges around already-problematic issues of inland flooding, salt-water inundation, and heat island effect. Highlighting why climatic shifts matter, Steinitz asked students about appropriate trees to plant at this location today. “Where are you going to look [for precedents]—Charlestown or South Carolina?” Considering that the latter approximates Charlestown’s expected climatic region in 2050, “I’d look to South Carolina if I were you,” Steinitz declared, “especially if the trees take thirty years to grow,” as many species do. This point, while seemingly simple, underscores an important reality: today’s designs must take future conditions and long-term repercussions into account.

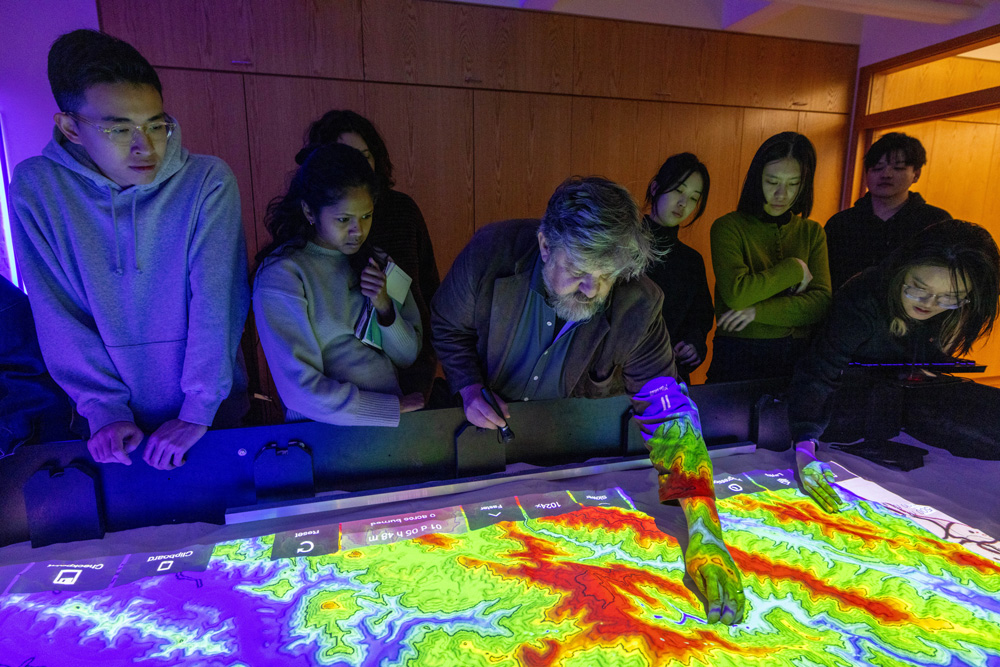

For the students, then, the GLG Climate Mitigation Project offers mitigation strategies for Boston’s climatic region that can be adapted for maximum impact in Charlestown. Once students have a particular strategy in mind, they can explore a different visualization technique—the Simtable . Invented by Stephen Guerin, affiliated with Harvard’s Visualization Research and Teaching Laboratory , the Simtable is a high-tech sand table that uses GIS data and computational modeling to explore complex phenomena, such as wildfires or chemical plumes, that involve people, places, and things interacting over time.

To demonstrate the Simtable’s interactive and projective capabilities, Guerin projected a topographic map of a fire-threatened Los Angeles region onto the sand. He asked the students to shape the sand by hand, following the map’s contours, building mountains and excavating valleys. Onto this modeled surface Guerin then projected satellite imagery of the area. Setting parameters such as time and weather conditions, he began testing scenarios for the fire’s progression and containment, using a laser pointer to select and implement different tactics. For example, how does bulldozing a trench from point A to point B impact the fire’s spread? What about sending resources to points C and D simultaneously? Or staggering them, while designating certain routes for human evacuation? The interactive simulations offer immediate feedback with minimal effort, facilitating a rapid iterative process for exploring, adjusting, and assessing interventions. Guerin’s ingenious tool has been employed numerous times during real-life emergencies, including the Los Angeles fires in January 2025.

For GSD landscape architecture faculty, the Simtable offers phenomenal possibilities to inform design. Bello envisions the table as a tool that could allow architects to “move back and forth between design and performance, exploring parameters in a more fluid iterative process” than afforded by conventional physical modeling techniques, which are notoriously labor and time intensive. Furthermore, Simtable’s interactive nature could enhance community participation in climate adaptation and mitigation planning, the success of which often relies on robust social engagement. As Bello notes, instead of showing data on a stationary screen, “you are projecting data onto [a tangible representation of] the territory, empowering people to construct that territory, which empathetically puts them in mind to act.”

Yet, before the Simtable can be employed by architects, experimentation is required. “We need to translate this tool into our field,” Bello says. “How might we use the Simtable, and how can it be used in landscape design? That is what we want to test.” And this is where the MLA Core IV students enter the picture. Just as the students tested Steinitz and team’s tools, Core IV faculty will continue to work with Guerin this semester to introduce the Simtable in early stages of architectural investigations, from site selection through design performance.

Of course, visualizing data is only part of the work undertaken by designers. Each site comes with its own history and current residents, who have with their own aspirations. Thus, in preparation for the Core IV studio, the students met with several people with strong ties to Charlestown. In addition to Steinitz’s and Guerin’s workshops, MLA students heard from experts such as Alex Krieger (GSD professor in practice of urban design, emeritus), who shared insights about Charlestown’s physical evolution; officials from the Boston Water and Sewer Commission, the Environmental Protection Agency, and other institutions, who discussed current plans for the neighborhood; and nonprofit leaders from organizations such as Boston Harbor Now, who work to address community needs. Students must consider all thisinformation and more as they assess and design for their urban site. The innovative methodologies embodied by the GLG Climate Mitigate Project and the Simtable will further support the students’ design efforts, now and in a future marked by inevitable change and environmental crisis.

- GLG Climate Mitigation Project collaborators include Stephen Ervin (Harvard GSD), Pedro Aresino (University of Lisbon), Tijana Dabović (University of Belgrade), Michele Campagna (University of Calgary), and Alex Killing (Yale Center for Biodiversity) among others. ↩︎

Five Lessons from the Gund Hall Renovation

In late May 2024, following commencement at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), the initial stage of Gund Hall’s multiphase renovation began. Designed by GSD alumnus John Andrews (MArch ’58), Gund Hall first opened in 1972, uniting the school’s three departments under one roof. Andrews’s scheme foregrounded the school’s pedagogical philosophy, apparent in the building’s shared studio block, which featured extensive glazing and 125-foot clear-span steel trusses. Described by reviewers as “visually dramatic ” and “a handsome structure ,” Gund Hall was received within the architectural community as a bold achievement.

The recent renovation, intended to make the building more climate friendly and comfortable for occupants, is equally bold, balancing the twin goals of conservation and innovation. Aside from serving as a paradigm for the preservation and revitalization of mid-twentieth-century modern architecture, the Gund Hall renovation offers valuable takeaways for clients and project teams. These five lessons suggest that, when introduced at the project’s earliest stages, collaborative decision-making sets a strong foundation for success.

1. Designate clear priorities