Meet Junainah Ahmed

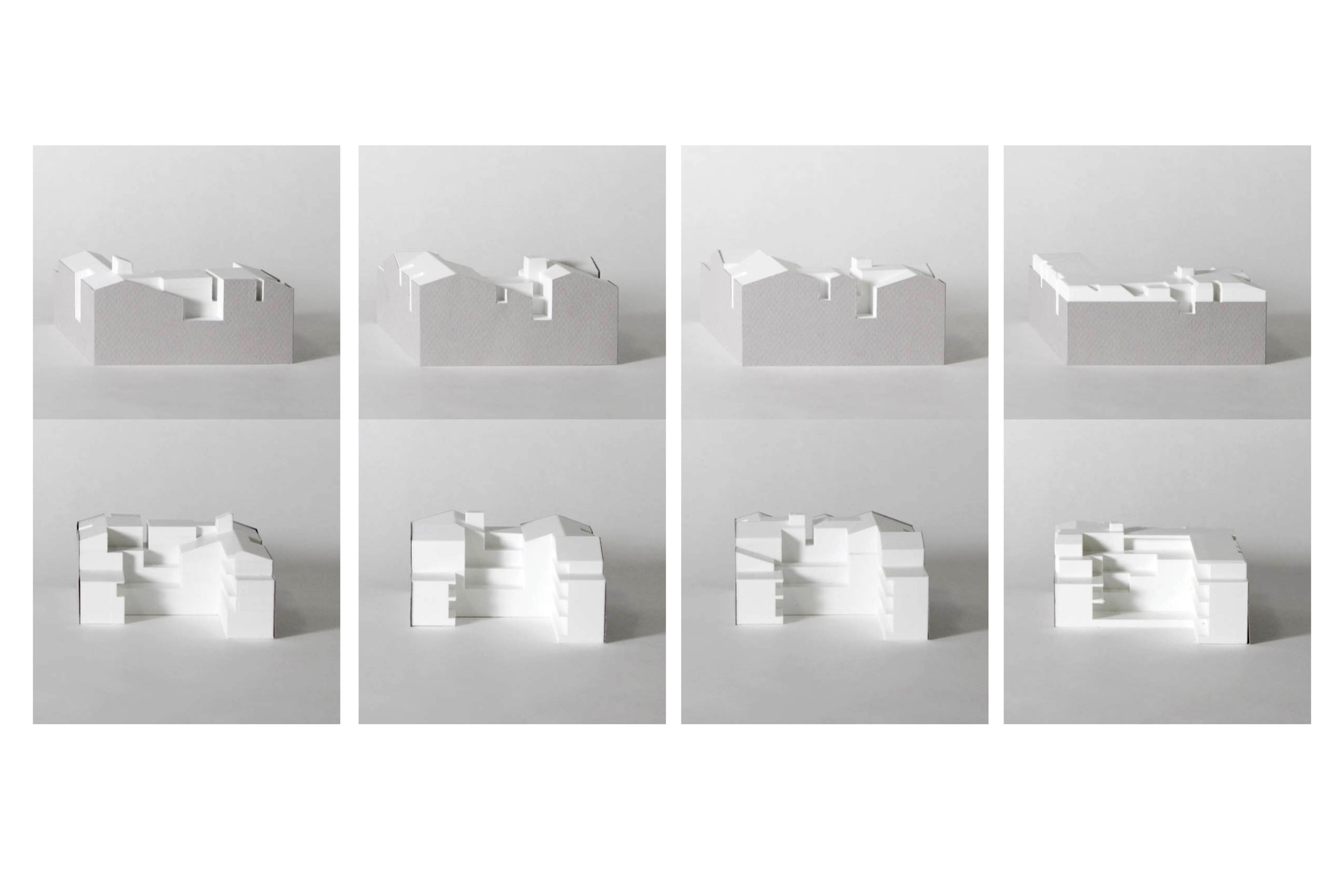

Junainah Ahmed (MArch I ’23) talks about the GSD classes that had a lasting impact on her thinking, including Core II with Michelle Chang and “Reflective Nostalgia: Alternative Futures for Shanghai’s Shikumen Heritage,” an option studio taught by Lyndon Neri and Rossana Hu. The MArch I program leads to an accredited professional degree intended for individuals who have completed a bachelor’s degree with a major other than one of the design professions or with a pre-professional undergraduate major in one of the design professions.

Alumni Spotlight: A Conversation with Eric Shaw

“On our very first day of school, [GSD professor] Jerold S. Kayden [MCRP ’79] said to me, ‘Being a planner can be a curse, because you actually live in your work and decisions.’ As I’ve grown in my position, that’s something I think about often. It helps me to be aware of the responsibilities and gravity of my actions, because I’m a consumer of my own choices.”

—Eric Shaw

Over the next couple months, we are continuing to share conversations with several GSD alumni, each of whom pursued different areas of study at the GSD and are now leading impactful careers in design.

We recently spoke with Eric Shaw MUP ’00. Eric has led planning and philanthropic organizations in major cities throughout the country, and has been recognized for his work in establishing strategic initiatives that support inclusive development and resilience in communities throughout the United States. A devoted mentor, he serves as an advisor to the GSD’s African American Student Union, the Harvard Urban Planning Organization, and Queer in Design, in addition to serving as a member of the GSD Alumni Council. Currently, Eric is the director of the San Francisco Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development.

How did you hear about the GSD and what led you to attending?

I went to UCLA for undergrad, and that’s where I came across urban planning. I took a course taught by [former Massachusetts Governor] Michael Dukakis, who wrote my letter of recommendation for Harvard. He really got me thinking about planning and policy programs. He said, “If you want to be a leader, don’t be a lawyer.”

I learned the language of community from UCLA, but I learned the language of design from Harvard. It was horribly hard that first semester, but my professors and fellow students really invested in me, and [the GSD] gave us all the tools we needed to intensely engage with the program. Everything I learned that first year changed my life.

Are there certain courses or professors that you feel have shaped the work you’re doing today?

Richard Marshall [MAUD ’95] was a new professor at the time. Like I said, I was really struggling my first semester, because I didn’t want to draw, and [back then] that was what the GSD was all about. Richard Marshall said, “Eric, I want you to succeed.” So instead of drawing, he made me write a five-page paper every time we met. He knew I knew how to write and speak, so he took my papers and made them into drawings for me. He was my Rosetta Stone that taught me how to bring those two skills together.

Oh, and I can’t forget M. David Lee [MAUD ’71], who I believe was the only Black GSD professor at the time. He’d say: “Go do it, brother.” Sometimes, that’s all you need.

Through your work on the GSD Alumni Council, you’ve spent a lot of time mentoring students. How did that begin?

I’ve been on the GSD Alumni Council for almost 10 years now; one time early on, [someone from the GSD] told me about this “Black in Design” conference, a three-day symposium organized by students. They invited Black designers, architects, and landscape architects from around the country and had one of the most prolific events around how we center Blackness and Black power. Telling the stories of Black accomplishment, Black innovation, and Black fame—I had never said “Black” so much at the GSD, as a student or alum!

The best thing was that it was run by students. The students came in and they felt empowered. A lot of them are my mentees now, and they’re also my peers. It was a single moment where the school was transformed. All those things really come from student leadership, [with students] mobilizing to shift the narrative of design.

“Black in Design,” hands down, has transformed [the GSD]. I probably know 85 percent of the Black students who have graduated in the past 10 years, and probably 60 percent of the queer students. I’m very proud to be paying it forward—like my GSD, UCLA, and professional mentors did for me. In every position I’ve held, I’ve committed to supporting future planning leaders with backgrounds not currently represented within the profession.

Could you tell us about the work you’re doing right now in the San Francisco’s Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development?

I have a community development organization in which I invest about $300 million a year in grants. Those grants go to supporting community organizations and cultural districts. We guarantee that anyone who’s up for eviction has the right to a lawyer, and we administer rental assistance for people with very low income to keep them housed. That’s my day to day—basically trying to align resources, policy, and politics to keep people in their homes, and making sure new homes are being built.

So, I’m functionally a realtor and a broker that matches low income people with apartments in buildings around the city.

Looking at the past decade, what have been the biggest changes and adaptations you’ve seen in housing and urban planning?

For a long time, economic development was the crux of planning: how do cities make more money to do more business? So we started focusing on things like revitalization, green spaces, and bike lanes—because those things made a place “nicer” and caused more people to want to live there. But, it’s “nicer” because we wanted a certain type of person—someone with taxable dollars—to go eat at a restaurant in town. We call that beautification. The planning was very intentional: creating beautiful places for a certain type of person that had the means to invest in the city, which would convince businesses to come.

The problem was: we didn’t think about making more housing because the focus was on “livability” and creating community amenities. So then: what about the people? The people, themselves, demanded it, and planners and politicians finally responded: “Oh, you’re right.”

Housing has become the key implementer for a lot of our goals: community stabilization, wealth building, transportation, climate change, and so on. It’s now all of these goals versus only the economic development of a space.

What about government funding—and funding in general—for housing projects?

The federal government has given us a lot less money. Now, a lot of communities have said, “We want to tax ourselves, but we want to have a plan for when we tax ourselves.” For the first time, there are a lot of local resources to advance planning. I think that, finally, the intentionality has changed.

San Francisco is one of the most expensive places to build—one of the most expensive places to live—in the world. Fortunately, we have a mayor who is deeply committed to advancing housing opportunities. My operating and investment budget is about $1.7 billion specifically for the investment in housing. I run an investment bank that invests billions of dollars with nonprofit developers to build new affordable housing throughout the city. We have a commitment that for any new large market-rate housing developments built in San Francisco, 20 percent of housing needs to go toward low-income residents. That’s been mandated for about seven years now; it’s called inclusionary zoning.

Why did you choose to work in San Francisco, specifically?

I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area and it is nice to be back home. The older I’ve gotten, the more freedom I have had to choose where I want to be. I’ve been so blessed to work in a lot of places, but as the adage says, “There really is no place like home.” Professionally, when an opportunity arose to work with Mayor Breed [in San Francisco] I was excited to support her vision and leadership—to feel a stronger familiarity with the communities where my team and I work.

Also, I became a planner because I’m deeply committed to advancing opportunities for African-Americans. I want to make Black people’s lives better. Under [Mayor London Breed’s] leadership, we went from five Black people in five years getting homeownership through our homeownership programs to 25 this year alone, with 100 more in the pipeline for next year. It’s great to be in a city that I love, a city with a mayor who I trust, and means to be a responsible steward of policies and resources. First working for [Washington D.C.] Mayor Muriel Bowser, and now Mayor Breed, I’m one of the only people in the country to have worked for two mayors who are African-American women.

Could you talk a bit more about the importance of diversity when it comes to planning and understanding the needs of a community?

In San Francisco, the housing authority director is a Black woman. The redevelopment director is a Black man. Our homeless director is a woman of color. We have a disproportionate number of Black people in homelessness, and we recognize that. And so there’s a deep sort of coordination around this. If the resources are there, I think we have a sense of urgency to act. And we did it. We had one of the lowest rates of unhoused people that got COVID. Everyone got a hotel room; 3,000 people have been housed. We moved them from the hotels and from their tents to permanent housing with more vouchers.

On top of that, as a Black queer person, it is so much fun to be subversive—to understand that there are layers to beauty, functionality, and usability that only discrete communities are going to use. That’s when I think the powers of design, agency, and leadership all line up.

How can planners continue to grow as leaders in their field?

By really, deeply engaging with the communities we’re working with. I always find it exciting when my training comes from organic moments working alongside a community.

I used to work as a development officer in San Jose supporting city investments in a predominantly Mexican immigrant community. One day, we had this barbecue in a park. Somehow, it got back to the women’s husbands that this non-Mexican man was trying to barbecue for their wives, and they were not happy about it. My Spanish is limited, but I knew they were saying: “No, you’re not going to cook for my community. We know how to do that.” They all came over with steaks and hot dogs, and you know what I did? I backed off, and just observed. I thought, “Okay, this space is different when women are with their husbands; so in our planning, we should have a bigger grill.” It was a beautiful space where men felt safe to engage with each other, express love for their families, and show grassroots leadership. My job was to pull back and observe, and I did.

My training as a student was so important—so, I’m going to tell one last GSD story. My first studio was with Alex Krieger [MCP ’77], and I remember he gave students 20 minutes to design our ideal town square. We drew them separately, and then everyone pinned them up on the wall. All of our town squares looked exactly the same, because we all came from western places—a park in the middle, a church here, and an ice cream shop over there. Every designer has an inherent bias. A trained designer understands that bias. From there, you either have to justify it, or learn the tools to unwind it and create the town square that the community actually needs. That’s the power of training; it’s an exciting power.

Alumni Spotlight

“My work is multi-layered and multi-disciplinary; sometimes it’s civic art, sometimes it’s planning, sometimes it’s community engagement, sometimes it’s architecture, sometimes it’s landscape design, and sometimes it’s a combination of everything.”

— Paola Aguirre Serrano

Paola Aguirre Serrano (MAUD ’11), is a GSD Alumni Council member and the founder of Borderless Studio , an urban design and research practice based in Chicago and San Antonio, focused on collaborative, interdisciplinary projects and civic engagement proposals that address the complexity of urban systems, spatial justice, and equitable design. Her experience includes working with government agencies, non-profit organizations, universities, and architecture/urban design offices in Mexico and the United States in projects at various scales—from neighborhoods to entire regions.

Where were you in your life and career when you decided to apply to the GSD?

I went to undergrad for architecture; very quickly after graduating, I had this fantastic opportunity to work with the government in my hometown of Chihuahua, Mexico, a community along the US-Mexico border. The municipal planning agency I worked with (IMPLAN) reached out to Alex Krieger MCP ’77, [Professor in Practice of Urban Design] at the GSD; he had been working with riverfronts in cities all over the U.S, and we asked if he wanted to [engage his students] to study the Chuviscar River in Chihuahua. He said yes, and that was the start of our relationship with the GSD.

It was a fascinating experience to host students from the GSD while sharing the aspirations we had for our city. I was very inspired by the experience and started learning more about the program. I had been working in urban planning for a number of years, but I was basically self-taught. After the experience with the GSD studio in Chihuahua, I realized that I needed more training because—working with the government and for the public—I knew that it was only going to get more challenging.

What drew you to pursue a Masters of Architecture in Urban Design?

At the time when I started, there was a lot of enthusiasm around the urban design program because it’s very unique. It felt like this gray area in which everyone was still figuring out how to operate. I knew that I wanted to be more on the architectural side with an urban influence and understanding, but I was always very uncomfortable with being put in a box in terms of practice, people saying: “you can only be a planner” or “you can only be an architect.” I wanted to understand it all, and to practice horizontally across different areas of work.

Can you share with us the origins and evolution of Borderless as a design practice?

The idea for Borderless started at the GSD; a Latin student group that I was involved in organized small exhibitions and programs because we wanted an excuse to have a conversation about the border between the United States and Latin America. People always end up talking about the same things when it comes to border communities. Borderless came from a place of wanting to talk about how cities are connected in different ways—water systems, environmental aspects, economic dynamics, multicultural identities: a combination of everything.

Growing up in Chihuahua and now reimagining how we design and plan border communities—how is your upbringing significant in terms of the work you are doing today?

The Latino culture planning efforts and the U.S. initiatives are very different, and it’s really fascinating having to design these hybrid processes. My experience having worked in government was foundational. Right now, for example, we’re working on a housing project near the eastern border of Brownsville, Texas—the majority of the population is Mexican or Latino. Being from Chihuahua, I can empathize and understand their culture; I can speak their language. The conversations we have with people need to happen in Spanish, but they also need to be meaningful and engaging.

We’re always thinking: how do we make this accessible and relevant to the communities that we’re working with? Our priorities as planners and designers need to align with the priorities of the community. The combination of empathy, experience, and knowledge helps me to engage with communities in a meaningful way in order to better understand what those priorities are.

You have also taught at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. How would you say discourse and education around urban design have changed in terms of how it is taught today versus when you were a student?

Since I started teaching at the Art Institute, I started to engage students in thinking about inequities and wealth disparities as a way of pedagogy. In recent years, especially during the pandemic, the impact of inequities became more visible than ever. It’s not that they weren’t there, they just weren’t considered as relevant for research and work. As designers, we have a responsibility to educate ourselves. We have to understand the root cause of problems in order to think of effective repairs, and particularly the role that design has played in the inequities that we experience today.

Looking ahead to the next decade as a designer, how do we build a new best practice? What changes do you hope to see in the field as a whole?

Designers have not done a good job engaging with communities of color. The majority of my work has prioritized working with black and brown communities; it’s very hard to pitch design as something positive to communities who have experienced decades of racism, neglect, disinvestment. That needs to change.

Also, I’m highly invested in climate resilience. Living between Chicago, Chihuahua, and San Antonio—I’m gaining more awareness of how our communities are going to experience huge challenges to adapt to changing climate and environmental conditions that are putting pressure on our infrastructure. These challenges need to be addressed on multiple scales—food systems, health systems, etc. These systems are very connected to climate and we need to think about how the design system responds to climate change as well.

How can designers continue to act as leaders in their field?

Traditionally, designers have had very little decision-making power. We are often just called at the end of project processes for design production, when we have the capacity to contribute so much more in the early stages or incubation of ideas. That puts pressure on our ability to wear multiple hats, to be more engaged and collaborate with other sectors, and seek to be part of larger conversations impacting funding and policy in our cities. When it comes to climate change policy, as designers, we are going to have to leverage our understanding of urban complexity at the global scale, while being able to translate strategies to local contexts. In the next couple of decades, we are going to see very dramatic changes in the ways our cities are designed. So how do we, as designers, become more active participants in decision-making spaces? How do we propose new collaborative frameworks to advocate for spatial justice and equitable design? That’s what I’m interested in.

Check out the links below to learn more about Paola’s work:

Creative Grounds is an initiative led by Borderless to explore the role of schools after the largest public schools closure in Chicago’s history, bring awareness to the impact of this inequity, and to engage community in collaborative interventions reimagining the role of social infrastructure.

Reclaiming Space in Hamilton Park

The Reclaiming Space project features a design installation in collaboration with Chicago’s Park District’s T.R.A.C.E. program (Teens Re-Imagining Art, Community & Environment) to reactivate the area of an existing handball court at Hamilton Park in the Southside of Chicago.

Walkability Guidelines for Social Infrastructure

Borderless collaborated in the creation of these design guidelines for access to essential public urban facilities.

National Museum of the American Latino

Paola serves on the Scholarly Advisory Council for the National Museum of the American Latino in Washington, D.C. The committee discusses and advises in items related to museum content: curatorial, collections, exhibitions, public program, education approach, and community engagement.

Curatorial Team for the Exhibit Columbus 2023

Paola also serves as part of the Curatorial Team for Exhibit Columbus – a biannual design festival that commissions/features designers/design installations to celebrate the legacy and future of design; she was previously a featured contributor in 2019.

Students in Dialogue

What’s it like to be a Master in Design Studies (MDes) student in the Narratives domain at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD)? In this series of candid conversations between students, Ian Erickson (Master in Architecture I ’25) speaks with CoCo Tin (MDes ’23) about merging research and design and her forthcoming book based on research supported by a Kohn Pedersen Fox Traveling Fellowship.

Ian Erickson: What ideas are most interesting to you right now?

CoCo Tin: Ideas of fluidity, gender, and East-West encounters have been on my mind lately.

What were you doing before you came to the GSD?

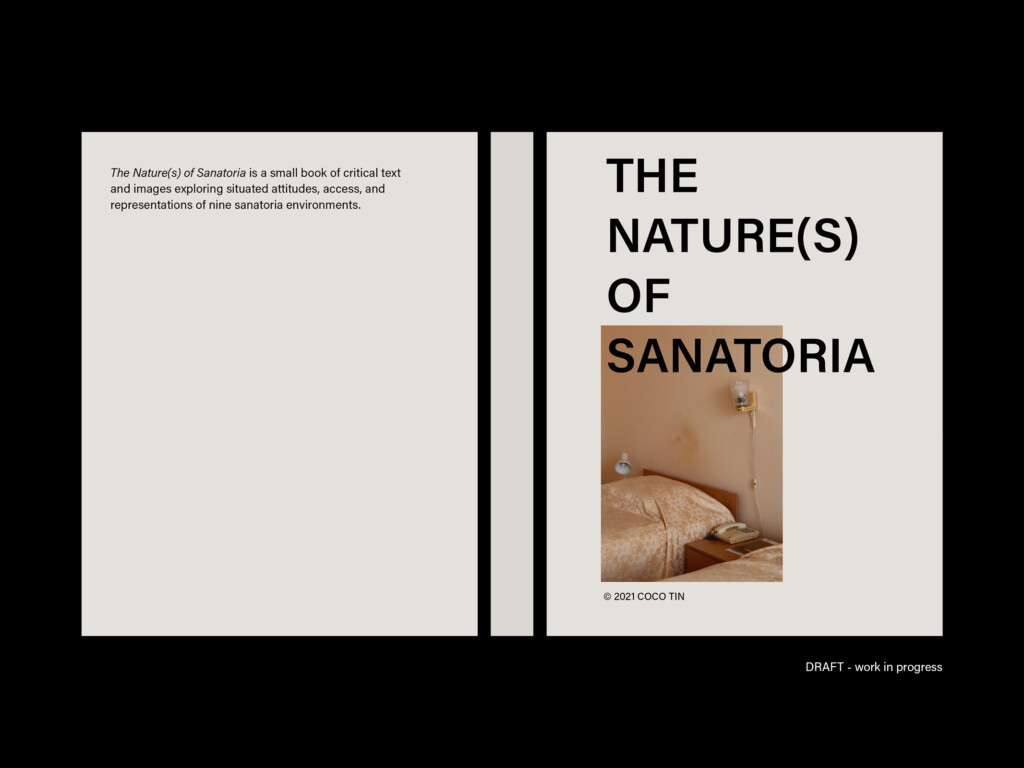

I graduated from Cornell in 2019 and worked for the architecture firms Food New York and Collective in Hong Kong. While at Collective, I continued my Kohn Pedersen Fox (KPF) Traveling Fellowship that began by visiting still functioning sanatoriums, compiling the body of research into a full-on publication. I cold emailed a bunch of publishers and got positive responses. So by April 2021, I had written a full manuscript first draft (56,000 words!). It was a productive balance of part-time design work paired with self-directed research.

What led to your decision to attend the GSD?

Having a Bachelor of Architecture (B.Arch) from Cornell means I spent five years going through rigorous design studios. Yet I always had an itch for history/theory that I never really got to prioritize. So the newly restructured Narratives domain of the MDes program stood out to me. In finding myself working part-time between designing buildings and doing research, I discovered that it was a limbo space I really enjoyed. I decided to get a formal master’s education in the history and theory side of architecture.

Was there a particular part of the program that made you want to attend the GSD specifically?

To be honest, I think it was Erika Naginski because she is so organized, articulate, and generous with her scholarship. Also, the program being two years long was appealing; it felt like the perfect amount of time to build on my sanatoria research work and enough to start something new. Also, the Womxn in Design’s Bib: An Annotated Bibliography on Identity Theories stood out. I was—and still am—craving a more ecofeminist approach to architectural history and theory.

Do you have any advice for preparing a portfolio and showcasing your work in order to apply to MDes?

I would say put your wackiest project first. The optional supplementary portfolio submission for Narratives was a writing sample. But in my portfolio, I also submitted a lot of design work because writing and visual thinking go hand in hand in my process. I think the program shares that sentiment since “Word and Image as Narrative Structure” is the title of the required proseminar course for the Narrative program.

What are some of your goals for after graduate school, and how do you feel the MDes program has prepared you to accomplish them?

To finish and officially publish my book! But even after one semester here, I’ve realized how much my thoughts have developed. For example, for the Ecologies proseminar with Chris Reed, I had the chance to rework the frame of my book and produce new writing with a more environmental focus. Rather than just seeing the building as a cure or as a space of care, I explored the sanatoria effect as closing the gap between the built and “natural” environment. My time in MDes has given me the tools to dissolve the nature-culture binary at large into a more complex and nuanced discussion.

That aside, I came in thinking that a PhD would be the next goal, but now I’m not so sure if that’s the immediate step post-GSD. As I mentioned, I want to stay in this limbo of design and research, so right now I’m exploring design at large. For example, this summer I’ve pivoted slightly and am working in creative strategy for spatial projects at 2×4. What remains strong is a deep desire—paraphrasing Lydia Pang—“to make the world a little less shit.” A natural step for this goal seems to be teaching. I’ve been lucky to be TA for MArch I’s Core II studio, and also for history/theory seminars. Doing that in tandem with RA work for Jeannette Kuo and the wide range of classes at Harvard and MIT has broadened my horizons in terms of applying spatial or architectural thinking across many projects with a social-environmental agenda: my aim is to go beyond the building. I think this sort of freedom for exploration has instilled a desire for some sort of creative professional and teaching practice before pursuing a PhD.

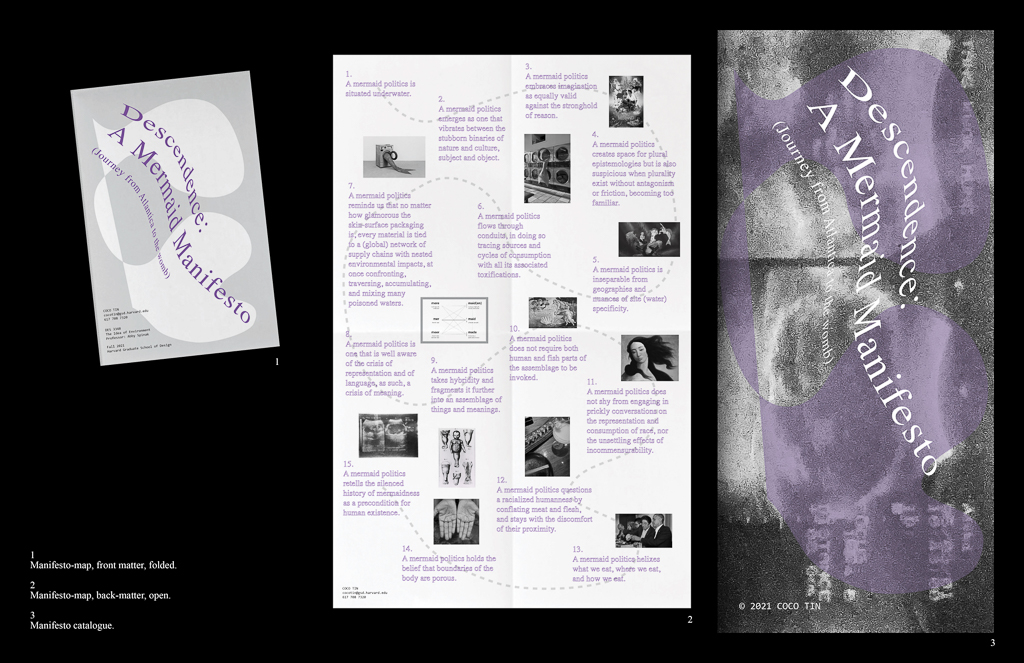

You taught a J-Term course (one of the GSD’s student-taught winter break term classes). What was it about?

My J-Term course, “Mermaids: An Amphibian Story,” built upon a radical archive (Descendence: A Mermaid Manifesto . . . Journey from Atlantica to the Womb) for Abby Spinak’s “The Idea of Environment” class. It was about mermaids and how thinking through this mystical and fluid creature can challenge the porousness of boundaries in our bodies and the environments that we occupy. Of course, the mermaid fascination is also a bit cheeky; it pushes back against the “male model figures”—e.g., Vitruvian Man, Modulor man—and their stronghold as the standard bodies for design. The work of Stacy Alaimo and Donna Haraway was crucial to my thinking. Mermaids are interesting because they emerge in almost every culture’s origin story but have been domesticated by Disney. For example, the legend ancestors of Hong Kong are the LoTing Fish (盧亭). They are half man and half fish, but not the usual hybridity that we imagine when we reference mermaids. So in a sense, mermaid-ness is also a way to spatialize the ontology of being hybrid. What does it mean to be inter-species and environments?

Do you have a favorite course? What has been exciting or challenging in your coursework?

The Narratives proseminar is still one of my favorites. I was skeptical at first, because we were reading Kant, Derrida, and other canonical grad school figures that are challenging to read, and don’t really discuss things like gender. But Erika set it up in a way where thinkers would be almost pitted against each other. The proseminar was structured so well as a methodology course that, to this day, things like Peirce’s triadic semiotics, or the study of signs, are foundational to my ongoing work.

Abby Spinak’s “The Idea of Environment” and a class at MIT in the Art, Culture, and Technology (ACT) program with the artist Judith Barry were both refreshing for their wide range of new philosophical and visual references.

Students in Dialogue

What is it like to be a Master in Architecture II (MArch II) student at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD)? In this series of candid conversations between students, Ian Erickson (MArch I ’25) speaks with Dutra Brown (MArch II ’22) about working on commissioned built projects while still a student, her decision to come to the GSD, and her post-graduation goals.

Ian Erickson: What ideas are most interesting to you right now?

Dutra Brown: I’ve been thinking a lot about embodied forms of knowledge. This past semester, “The House: A Machine, Queer and Simple”—the option studio co-taught by Andrew Holder—participated in movement workshops led by the artists Gerard and Kelly, who also co-taught the studio. The workshops informed our architecture projects by giving us an alternative way of thinking about how we as designers articulate and define space.

What were you doing before you came to the GSD?

I was living in Los Angeles and getting my bachelor of architecture from the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc). The summer leading up to the start of the fall semester at the GSD I was working on a design-build pop-up for a wellness retail company called Flamingo Estate in Los Angeles. I was actually only able to do the project because school was remote, and so I was able to stay in Los Angeles and see the build-out through. I completed the project with a collaborator, ceramics artist Alex Reed, who also needed to be close to the project, as we were fabricating a lot of bespoke ceramic tiles. It was the first design project that I did under my own name that got built in real life, and it was incredibly rewarding to watch unfold while I was balancing the academic work of the first semester of graduate school.

What led to your decision to come to the GSD specifically?

I actually did the GSD’s career discovery program in 2013 after my freshman year at NYU, where I was undeclared. I loved it so much that I immediately transferred into an architecture program for the remainder of college. Given that attending the summer program was a huge turning point in my life and education, I really wanted to apply to attend the GSD for a full degree program. Also, the faculty here are very engaged in their own built practices, which I wanted to learn from. The vibrancy with which the GSD approaches building was very exciting to me and also distinct from my undergrad degree, where I was working on a lot of speculative projects. So, for me, it was also an attempt to jump outside of my comfort zone.

Did you have a favorite course at the GSD?

My favorite course was my most recent studio with Toshiko Mori, “Between Wilderness and Civilization.” The studio brief was to design your own program for Monson, Maine, an aging rural town that currently has 600 residents and a lot of job loss due to the recent closure of a paper mill and furniture manufacturing company. The Libra Foundation is investing in the town’s future by calling for proposals to construct an innovation lab in a 72-acre abandoned farm located right outside of town. We had a lot of conversations with people who lived in Monson and other stakeholders, and it became almost like a thesis, where you have to choose your program and understand the social, political, and economic implications of the program that you’re choosing. It made me realize there is all this work that you have to do before you even touch design.

How have you grown through your graduate studies at the GSD?

I think becoming more aware of how design intentions are read by communities outside of the design field has been formative for me.

What are your next steps now that you’ve graduated?

This summer I’m working to finish up the design of an ongoing interior renovation project for two guest cabins. The project makes use of some recycled material from the pop-up that I was talking about previously; so the first thing I worked on when I started at the GSD is also going to be the thing that brackets the end of my time here. Hopefully by the end of next summer we will break ground on construction. It’s really fulfilling to be able to take what I have learned about design and building during grad school and immediately apply it to real-world projects.

Editor’s Note: This conversation was conducted in Spring 2022. Dutra Brown graduated with the class of 2022 and is now based in Los Angeles.

Students in Dialogue: A Conversation with Maximilian Mueller

What is it like to be a Master in Design Engineering (MDE) student at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) and the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences ? In this conversation, Ian Erickson (MArch I ’24) speaks with Maximilian Mueller (MDE ’22) about his background in neuroscience and music production, taking classes across the university, and working on a forthcoming PlayStation video game.

Ian Erickson: What ideas are most interesting to you right now?

Maximilian Mueller: Lately I’ve been thinking about the ways our mediasphere is moving towards including more deliberately mutable digital works. For instance, an MP3 that constantly evolves based on some latent intent of its author or in response to its context, rather than simply being a static digital file like we are used to.

What were you doing before you came to the MDE program?

My academic background is in neuroscience and my past work ranges from zebrafish teratology to music production, data mining, and behavioral health. Most recently, I’ve been focused on music—writing for commercials, TV, and other artists.

And what led to your decision to attend the MDE program?

I wanted to integrate and formalize disparate interests such that my creative and professional practices could merge in a productive and economically viable way. Harvard University, and specifically the MDE program, which is housed between two separate and exciting schools—the Graduate School of Design and the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences—seemed like the ideal place to do that.

Can you reflect on how you’ve grown so far through your graduate studies and what you’re looking forward to in the remaining time you have here?

Just being at an institution like this is eye-opening in so many ways. You are exposed to so many new ideas and people; I’m still parsing what it all means! I’m particularly grateful to have met the people at metaLAB—I’m currently working on sonic interface design for their Curatorial A(i)gents project, to be exhibited next year in the Harvard Art Museums ’ Lightbox Gallery.

As I near the end of my time here, I’m looking forward to pushing the integration of arts/design/engineering as far as it can go, both through my thesis and through the video game I’m working on.

I’m really excited to hear more about the game!

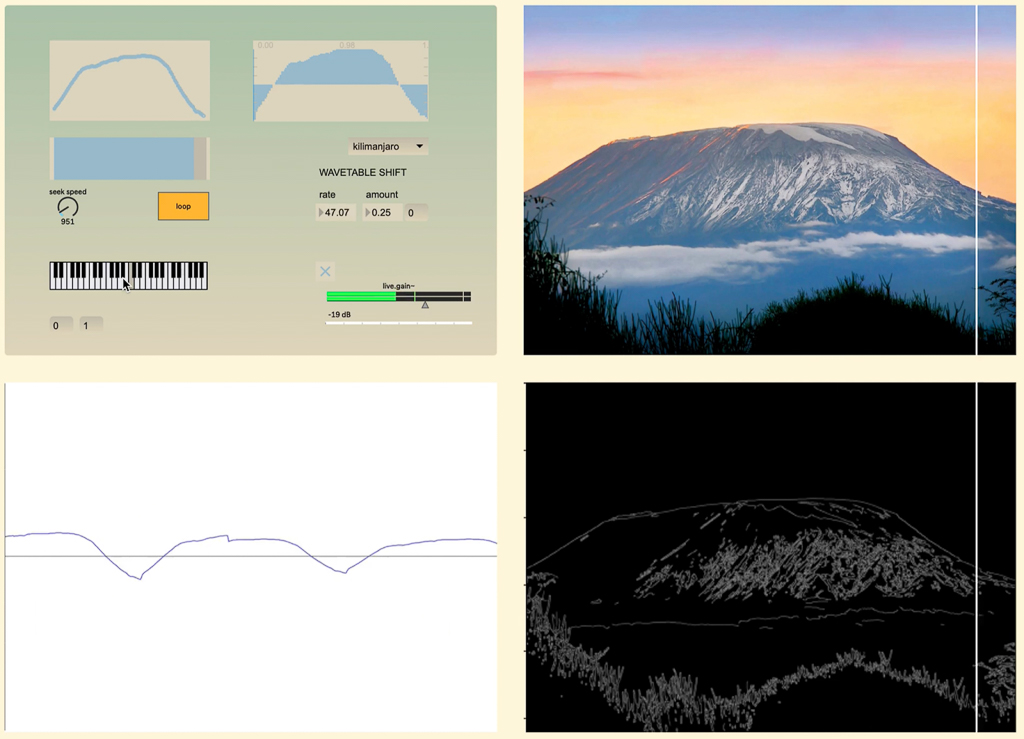

The game is called Nour: Play With Your Food, out of an indie studio called Terrifying Jellyfish, published by Panic, and out on PlayStation later this year. It’s an art game that explores food aesthetics, culture, and memory through free-form play. It asks whether virtual food can look so good that you can taste it. Can visuals and sound alone evoke the sensation of hunger?

I was initially brought on to do the soundtrack. Coming in, I had no game development experience and I am not much of a gamer, so I didn’t really know what I was getting myself into. Yet, it quickly became apparent to me that a static soundtrack wouldn’t do—it had to be generative and integrated into gameplay mechanics. In this way, the game functions as an instrument that anyone can play: conjure food and make a melody, create a dish and make a song. Gameplay has some immediate and structural sonic consequences; the soundtrack is created in real time, based on the nature of player behavior. Music in Nour acts not just as a soundtrack, but as an interface. Players can exert influence over the scene and its contents in both familiar and new modes of musical gameplay, using rhythm, pitch, and volume as a language of sorts. A lot of thought went into making the sonic interface accessible to a first-time player yet rewarding to someone that’s “mastered” the instrument.

Being invited to write some music spiraled into a heuristic exploration of this incredibly rich medium. My coursework during the first year of MDE prepared me to come into a new discipline cold, use my design thinking skills to imagine something novel in that arena, and apply my growing technical skills to make it happen.

Can you tell me about a favorite course you’ve taken at the GSD?

One of my favorites was an MDE core class called “Integrative Frameworks,” taught by Professor Woodward Yang. I’d describe it as a polymathematics seminar. We did a few hundred pages of reading a week on subjects ranging from universal design to IP law, political economy, and physics. We would then analyze and discuss the modes of thought and the structures supporting the ideas, with the goal of integrating other frameworks.

How is the MDE thesis structured and what are you working on for it?

The MDE capstone or IDEP (Independent Design Engineering Project) is a year-long thesis focused on systems-level interventions. For my IDEP, I developed an aural AR framework that grants people new senses and enables media to react to a user’s context in real time.

Can you speak a little bit about your experiences taking courses outside of the GSD?

Given the dizzying array of wonderful classes at Harvard, it’s a challenge to decide on (and then lobby for) the perfect course. I’ve taken quite a few outside the GSD and would say that generally GSD students’ design perspective is valued highly in non-GSD classrooms. What is second nature in Gund is not elsewhere. The same goes for the perspectives and frameworks of the host schools when their students take courses at the GSD. It’s that collision and integration of frameworks that I love most about my time here.

Editor’s Note: This conversation was conducted in Spring 2022. Maximilian Mueller graduated with the class of 2022.

Shigeru Ban in Conversation with Mohsen Mostafavi about Designing for Refugee Relief

In the early weeks of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Pritzker-winning architect Shigeru Ban flew to Chełm, Poland, to aid in the development of refugee shelter infrastructure. In a conversation with Mohsen Mostafavi, he discusses his experiences designing and producing partitions for large shelters after the 1995 Kobe and 2004 Niigata earthquakes in Japan, and how designers can apply his techniques to emerging crises in Ukraine and across the world.

This interview was conducted for the In Conversation series on japanstory.org , a multifaceted research project at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. Japanstory.org conducts its work through academic activities, as well as design research, while inviting people from a variety of fields to share their voices, viewpoints, and ideas as we think together about the future of the city.

Inclusive, Accessible, Subversive: Jenny French on a New Model for Cohousing

Bay State Cohousing, a 30-unit cohousing community, is neatly woven into the low-density neighborhood fabric of Malden, Massachusetts. Slated to open this summer, the award-winning project from Jenny French and her practice, French 2D , is redefining what high-quality and community-oriented housing can look like in Greater Boston, especially in the face of growing unaffordability and displacement. It is spearheaded by an intergenerational group of residents seeking support, friendship, and collectivity through housing, and is one of just 200 official cohousing projects in the United States. French2D—with their predilection for “strange housing, ” and focus on matching familiar ideas of home with more radical typologies—was the right practice to bring this cohousing dream to life.

As one half of French 2D and an assistant professor in practice at the GSD, French is deeply engaged with local issues of collectivity, housing, public space, history, and identity. From Bay State Cohousing to her 2022 core studio, “Kinship and Crises of a Near Future,” French is re-centering who collective housing can be for, what it can do for a neighborhood, and how municipalities can be more amenable to its development. In a recent conversation over Zoom, French spoke about the process behind designing the Bay State Cohousing project, the importance of relationship-building as a designer, and why she is optimistic about the future of cohousing.

Bay State Cohousing was recently named winner of Architect Magazine’s 67th Annual Progressive Architecture Award. Let’s start there: tell me about this exciting project.

Bay State is a 30-unit cohousing community just north of downtown Boston and well connected by the MBTA’s Orange Line. The project is an intentional community following the North American cohousing model, and is comprised of individual living units, which are connected to the larger framework of a “common house,” including terraces, yards, a dining room for 100, music room, living room, community pantry, and more—all designed to support a set of shared experiences and resources. Allowing for mutual aid, friendships, and families of choice, and the pooling of certain resources while maintaining individual household ownership and separation of finances is in many ways a subtly subversive counter to normative multifamily housing.

Though often conflated with other forms of collective living like cooperative housing and co-living, cohousing follows a fairly narrow definition and is modeled after quite specific Danish precedents from the latter half of the 20th century. The model’s success is well documented, but it does run the risk of falling into the “box” of pro-progressive housing models that end up being unintentionally inaccessible. At French 2D we are particularly interested in finding new avenues for cohousing as a more inclusive and accessible model.

What’s the origin story of this project?

The community began with two demographic blocks: people who, at the beginning of the process, were not yet 30 and others who were in late-middle age. Throughout the design process, the community has grown. The soon-to-be residents represent a range of family types and life stages, including multigenerational families, singles, single parents, and retirees, who together form a network of ready and willing friends, caregivers, surrogate grandparents, and more. The shaping of the community is defined not just by the current situation of each resident, but through envisioning shifting relationships, changing and aging bodies, and future members. This has become an essential frame of reference for the whole group—making all decisions with accountability to the collective community.

The project is now nearing completion; our involvement began in 2016, but the group formed several years before that over a mutual longing for collective living and social connection.

Do you think the pace of the project was essential to its success?

Time is a vital resource in this type of work. Other such communities have taken a decade or more to materialize, and though the time investment and journey enrich the project, we are keenly aware that expanded equity and access to alternative housing models calls for routes to get to similar results more quickly. I don’t think a “slow” process is the only way, but I think this project’s success, particularly in navigating the uncertainty of the past two years, relies on a strong tenure of relationships.

We were certainly met with challenges in local zoning. Shortly after the design phase began, the municipality announced a building moratorium followed by selective downzoning—on the project site in particular. To make a long story short, a series of setbacks for the project led to one of its brightest spots: the creation of a new cohousing zoning ordinance allowing (modestly) higher residential density tied to shared spaces and self-governance.

Looking at the project plans, it fits quite seamlessly into the majority single-family neighborhood. How is this context reflected in the architectural and spatial design?

After years of searching for a site, this was the most urban, closest to public transportation, and largest site that was economically feasible for our clients. It’s a ¾-acre site, but the anticipated program could easily fill 1½ to 2 acres. The project is in many ways a giant house in which individual units are analogous to private bedrooms connected by the communal spaces.

We took advantage of stacking and interlocking units, interior common spaces, and exterior common spaces, because we could not reproduce the horizontal spatial arrangement typical of North American cohousing. The constraints on the size of the site and desired program also created an ethos of abundance despite limited space. Specifically, in the private units, we shaved off bits of square footage to consolidate and give back to common spaces. Stacking and interlocking allowed us to embed social, visual, and visceral affordances into the body of the building.

The courtyard and balcony arrangement offers collective space where residents can connect in a supportive way. How can designers introduce this concept on a smaller scale to bolster the everyday experience of children and families in existing built space?

We looked for natural points of intersection in the spaces where adults could be needed and easily invited to participate in childcare. Specifically, the interior courtyard and lawn are overlooked by half of the units and all of the common spaces, each of which have exterior access at every level. Rather than being about surveillance, these connections create reciprocity across multiple places for gardening, chatting, playing, reading, or lounging. Many of the community’s older residents and those with children chose these courtyard-facing units to be near to one another, to the garden in the terraced beds at the rear of the site, and to the informal playspace on the patio.

As a baseline of multifamily housing, it’s important to include kids in the spaces of everyday life. I like the saying “Feminism is the radical idea that women are people,” and I think the acknowledgment that kids are people and members of society is an important one. This then translates to creating boundaries in design that produce both freedom and autonomy and a set of fail-safes to connect children to life within the community.

Based on this experience do you feel optimistic about the future of cohousing?

Absolutely! It’s important to recognize the need for a continuum of collective housing models to address challenges of affordability and density. If we think about Cambridge, there are many instances of single-family homes next to duplexes or larger multiunit apartments, a condition that American suburbia is certainly allergic to. How can we create more instances of 5, 10, even 20 to 30 unit buildings next to single-, two-, and three-family homes to allow that kind of variation while also improving the fabric of neighborhoods? That is the question that cohousing can begin to address.

Looking more broadly at your work, “care” and “collectivity” are consistent themes, yet in architectural practice both seem to be teetering on the edge of being buzzwords. How is French 2D working to ensure practice in this space remains intentional and critical?

This is a timely and hard question. I want to caution against rendering words useless and empty through overuse, and in doing so dismissing gigantic and critical areas where there’s work to be done. Since our start, French2D has centered on relationship-building, trying to think about how we go from being strangers to roommates, to friends, or to colleagues. We ask these questions not just of housing, but of a host of design elements, down to materials and small objects. To that effect, discussion around domestic space and mutual support within it, is inevitable and overdue.

I’m interested in the ways that a reemerging focus on feminist narratives from individuals like Silvia Federici or bell hooks or Dolores Hayden can expose the things that all of us share. For example, how do you look after an aging parent? Or how do you nurture a child who is not necessarily your own? These narratives posit that these are not individual challenges, but are shared necessities. I am interested in how the built environment is implicated in this essential work.

The GSD’s Early Design Education Programs: An Interview with Megan Panzano

Megan Panzano

In 2021, the Harvard Graduate School of Design invested in a set of short introductory education programs that are directed at sharing the value of design with the global public. Early Design Education (EDE)—which invites different audiences to “think and make” through design—includes Design Discovery Virtual, Design Discovery in-person, and Design Discovery Youth summer programs; the Black in Design Mentorship program; and the Harvard Undergraduate Architecture Studies program.

Last June, Megan Panzano was named senior director of Early Design Education to lead these programs in refreshed formats into the future. Harvard GSD’s Joshua Machat talks with Panzano about her plans for the EDE programs that include breaking down access barriers to design education, engaging diverse perspectives on what should drive design, and building a robust support system for students and those new to teaching design.

The Early Design Education programs introduce design ideas and practices to a wide range of audiences on a global scale. What are the methodologies students will be engaged with concerning the impact of design on the built environment and its potential for societal change?

The programs offer a great chance to share the value of design with an expanded public, and reciprocally, to include and value the voices that a diverse public brings to design. We’re invested in these programs bringing new forms of design agency to the individual ideas and perspectives of our global participants. And we’re working on making these programs as accessible to as many people as possible.

The “early” part of Early Design Education is not an age-dependent term. Rather it assumes that each program is one of the earliest experiences of design immersion and “thinking through making” that participants—ranging from mid-career professionals to high school students—have encountered. These programs aim to offer thoughtful instruction in the materials and scale of design across architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning and design; workshops in tools used for design, such as 3D modeling and graphics programs; and, most critically, how to think about the world through a design lens.

Harvard GSD Design Discovery Youth

The programs emphasize design as a method for asking important questions. The world is, and will continue to be, unavoidably instable—environmentally, politically, and socially. Our crafting of the Early Design Education programs accepts and claims that instability as a material of design. Rather than seeking a singular “right” answer or achieving a prescribed outcome, the programs teach how to use design to keep up with this evolution—to continuously question the world as we’ve come to know it. This happens by closely reading our context, seeing something that could be improved, naming it as a question, and directing design to impact it.

How has remote learning in the past two years impacted the EDE programs?

The required remote learning of the past two years has taught us many things, not all good. But there a few wonderful takeaways that we intend to hang onto. These positive qualities made it possible for us to conceive of a new format for our summer program, Design Discovery Virtual, which we will offer along with a refreshed version of our Design Discovery in-person program this summer and going forward. What’s been great is that now we have the chance to be intentional with constructing a virtual design education program, rather than simply reacting out of necessity of pandemic pressures.

We can easily bring diverse groups of people together from anywhere in the world to discuss design. That range of perspectives is incredible in conversation and as a way to expand one’s thinking. Within the context of our new virtual program, we note that peer-to-peer learning occurs as much as more conventional top-down organizations of learning from instructors.

Our virtual mode these past years has allowed us to learn and become quite good with programs, such as Miro and Slack, that make it easier to share work—both in-process as well as more polished—to collectively see and record design steps. Miro’s open virtual pin-up space visually collects elements in design processes and in works in progress such as drawings, 3D model images, design precedents and texts, and puts these on an equal plane with more complete finished final work for all members of a design studio. Because you can see your own design evolution beside those of your classmates, the program visually maps different learning paths along with design outcomes, a kind of meta level learning about learning. It’s a wonderfully powerful tool for those new to design.

Harvard GSD Design Discovery Virtual

Sharing our ideas via virtual platforms requires us to be more clear and intentional with an argument and a narrative for our design work when presenting. As opposed to more conventional academic design presentations where a field of visual and modeled work would be pinned up and shown all at once to an audience, digital programs tend toward linearity of flipping through a presentation one slide after the next.

How do you see students in the Harvard Undergraduate Architecture Studies program benefiting from the interdisciplinary approach that teaches design “thinking through making” within the liberal arts context?

The Harvard Undergraduate Architecture Studies program is a special one within the EDE set because it is a joint endeavor between two schools at Harvard—the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and the Graduate School of Design. It’s a track of study within the history of art and architecture concentration, or major, at Harvard. The GSD has created and teaches four making-based courses annually as part of this degree of study. These courses draw architecture studies concentrators, but are also in high demand with computer science, engineering, history, and visual studies students. We teach architecture to undergraduates, not with the expectation that everyone will become a designer, but with the goal that those coming through our courses who go on to shape the world in any number of ways afterward, will do so with a true understanding of the value of design.

What new offerings are available in the undergraduate Architectural Studies program for students seeking more experience in design education?

I’m looking forward to launching a new version of a course that went on hold for the past two years: a lecture/workshop class next fall for Harvard College students on climate change, through design. The course will explore how material selection and construction practices could radically shift if driven by more sensitive and careful environmental concerns. The course will also study the formal and spatial outcomes of using entirely new building materials and assembly techniques.

It’s been a pleasure to have the support and enthusiasm of my colleagues in the History of Art and Architecture Department, David Roxburgh and Jennifer Roberts, to develop a process for students wishing to pursue a design thesis in their senior year at Harvard College. Going forward, this will be an honors-eligible option each year for our Harvard Architecture Studies students. I’m looking forward to working with more undergraduates pursuing design research on topics they are passionate about as an additional path of studying the impact of design on the important issues of today.

The EDE programs place a lot of emphasis on supporting design teaching opportunities for the current advanced students of the GSD. What are these opportunities and what structures are in place to develop teaching skills in design across all three disciplines?

Harvard GSD Design Discovery

All of our EDE programs intentionally involve advanced GSD students as design instructors so that our current graduate students can gain design teaching experience, across all disciplines. We’ve been making some adjustments so that the programs in the EDE set call upon our GSD students to engage a different audience through different educational formats, and with varying degrees of agency to shape the design curriculum of the program. The intention is that the EDE programs provide a spectrum of design teaching experience that could build up if followed in sequence by current GSD students to help bridge them to post-degree academic positions. Our Design Discovery summer program, which has been around for more than 20 years, has a great track record of launching teaching careers in complement to design practice.

The Black in Design Mentorship program is rooted in the recognition that everyone benefits from mentorship, but not everyone has equal access due to racial inequalities and histories of disenfranchisement. What do you see as the most important factor in diversifying the design profession?

Members of the Black in Design Mentorship Class of 2022 visited Gund Hall in May to tour the building and celebrate the end of the program.

Recognizing and reevaluating what has been established, consciously and unconsciously, as “gate-keepers” to design is most pressing. This includes representation—seeing others like you in design and being able to project a path for yourself like theirs; affordability—considering the cost and time necessary for design education and professional licensure; geography—connecting design and its capacity to change the world as we’ve come to know it to the full range of global cultural heritages; and a sensitivity to the language we use to talk about design. If our profession is not appearing accessible to a diverse audience, one or more of those things are critically off. The design profession should be as diverse as the world we design within and for.

I’m honored to be working with a team of staff, students, and faculty who value these factors within the fields of design: Jenny French, Montserrat Bonvehi Rosich, Yun Fu, Kelly Wisnaskas, Ian Miley, Tosin Odugbemi, Rania Karamallah, Caleb Negash, Shaka Dendy, K. Michael Hays, and Sarah Whiting. Dean Whiting’s investment in Early Design Education has been critical in supporting the exciting plans we have to broaden design’s reach.

Excerpt from Pairs Issue 02: “Labyrinth of Affinities” by Jorge Silvetti with Nicolás Delgado Álcega

Pairs is a student-led journal at the Harvard Graduate School of Design dedicated to conversations about design that are down to earth and unguarded. Each issue is conceptualized by an editorial team that proposes guests and objects to be in dialogue with one another. The following is an excerpt of a conversation from Issue 02 between Pairs co-founder Nicolás Delgado Álcega (MArch II ’20) and Jorge Silvetti, Nelson Robinson, Jr. Professor of Architecture at the GSD, titled “Labyrinth of Affinities”

Pairs is a student-led journal at the Harvard Graduate School of Design dedicated to conversations about design that are down to earth and unguarded. Each issue is conceptualized by an editorial team that proposes guests and objects to be in dialogue with one another. The following is an excerpt of a conversation from Issue 02 between Pairs co-founder Nicolás Delgado Álcega (MArch II ’20) and Jorge Silvetti, Nelson Robinson, Jr. Professor of Architecture at the GSD, titled “Labyrinth of Affinities”

On Perspective, Anamorphosis, and Repositionings

The following conversation developed through a series of periodic exchanges that took place between September 2020 and March 2021. As a series of social events unfolded – at the GSD, in the United States, and around the world—the authors opened up a discussion that began with a set of personal notes that Jorge Silvetti had collected in the months prior. Alarming current events catalyzed a slow discussion, one in which personal experiences, disciplinary issues, and large cultural processes constantly intertwined through an exchange of words and images; one through which the authors, both raised surrounded by a degree of social unrest, sought to make sense of what they saw around them. This conversation took place amidst Silvetti’s retirement from the GSD after 46 years of involvement in the school. It accompanied the donation process of the Machado & Silvetti archive to the Frances Loeb Library and paralleled a seminar at the GSD in which related issues were engaged through a different mode. It precedes a retrospective exhibition of the work of Machado & Silvetti and has been a sounding board for a new course that Silvetti will teach as a Research Professor in the coming years. It is a conversation between two South Americans from opposite ends of the continent and on opposite ends of their professional careers who are both curious, concerned and stimulated by this moment in the history of architectural culture.“The worst labyrinth is not that intricate form that can entrap us forever but a single and precise straight line.”—Jorge Luis Borges, Labyrinths, 1962.

ar·chive | ˈärˌkīv | noun 1. a collection of historical documents or records providing information about a place, institution, or group of people 2. the place where historical documents or records are kept verb 1. place or store (something) in an archive

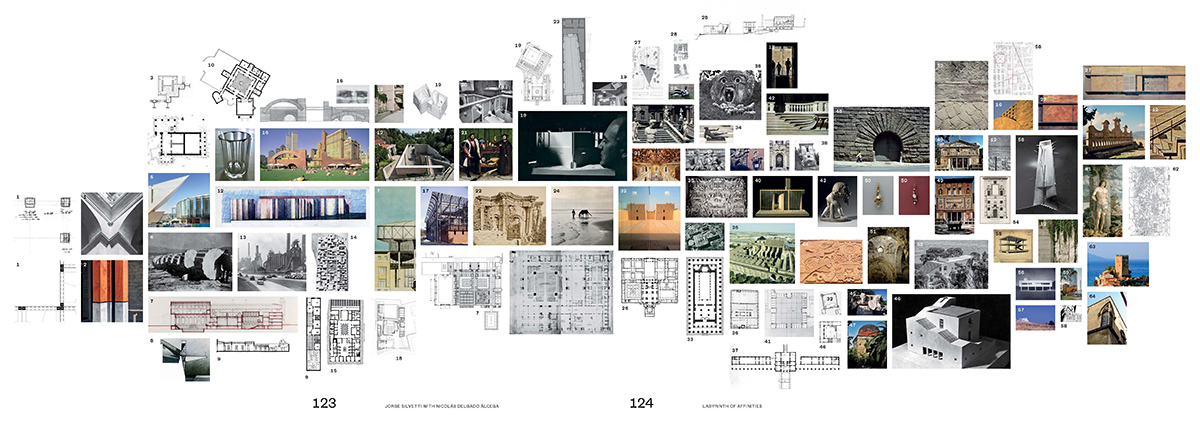

NICOLÁS DELGADO ALCEGA: In preparation for our conversation, I have been going over your office’s three monographs, because I wanted to have a discussion with you about your long-standing interest in the history of architecture. To that end, the projects in the monographs that you and Rodolfo produced in Sicily over the years struck me as a good place to start. How did you get to Sicily? And why did it capture your professional and intellectual attention for so many years?K. Michael Hays, Unprecedented Realism: The Architecture of Machado and Silvetti. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 1995. Rodolfo Machado, Jorge Silvetti, Peter G. Rowe, and Gabriel Feld. Rodolfo Machado and Jorge Silvetti : Buildings for Cities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 1989. Javier Cenicacelaya, Íñigo Saloña, and Nader Tehrani. The Work of Machado & Silvetti = La Obra de Machado & Silvetti. San Francisco Bay Area: Oro Editions, 2018.

JORGE SILVETTI: Before I answer your question, let me first say that I was chiefly educated within the context of the Western tradition but from a distinctly marginal location. I was raised in Buenos Aires, a city at the bottom of the Western world, in the southernmost tip of the continent. At the 34th parallel south, I was not only literally at the geographic bottom of the world but also on the fringes of the history of Western society. When I say marginal then, I mean simply that I was in a position at an edge farthest away from the centers of cultural dominance. From Buenos Aires everything was far, particularly those centers of power and their histories. This was amplified by the fact that, back then, people didn’t travel that often to Europe. To do so affordably meant a monthlong journey by boat, and even that option was not available to middle-class families. Nonetheless, everything I was learning in school—music, history, art—was invariably founded on the Western tradition. It was assumed that everything you were learning was the way it was supposed to be, which I suppose today means “canonical.” But I grew up feeling that whatever my reality was, it was upended from that “normality.” So, my understanding of the “canonical” was always inevitably skewed by the particular angle from where I had been positioned by fate, where distant traditions were intertwined with other local cultural ingredients that fed my mind and imagination. In marginal positions, local cultural pressures are inescapably very active. This is particularly true in the arts, language, and daily customs, whether it’s classical or pop music, painting, literature, cuisine, or local jargon.po·si·tion | pəˈziSH(ə)n | noun 1. a place where something is located 2. a particular way in which something is placed or arranged 3. a situation or set of circumstances that affect one’s power to act 4. a person’s point of view or attitude toward something verb 1. put or arrange something in a particular place or way 2. promote a product 3. portray or regard someone as a particular type of person

All these elements that were bound by location coalesced into my individual cultural profile. They contaminated my understanding and regard for the “canon”—my way of seeing it—and importantly influenced and inspired my creative and intellectual work. I think it all points to my particular, seemingly deviant predilections and interests among the canonical expressions of Western architecture, which are generally found in places that were far from the accepted “center,” be it Athens, Rome, or Paris. Even though Hagia Sophia or El Escorial were presented as part of the canon, I was always inclined to interpret them as marginal. I found them to be anomalies, deviations, or even perversions by which I was fascinated.re·gard | rəˈɡärd | noun 1. attention to 2. best wishes verb 1. consider (something) in a specified way 2. gaze at steadily in a specified fashion

However, these conditions not only determined my interest in certain cases on the edge of the canon but also influenced my reading of works squarely in line with the “canon.” At one point, I even convinced myself that the whole Palladian oeuvre was a peculiar, provincial oddity of the Roman Renaissance. Although I used to be somewhat embarrassed of myself for holding these positions—keeping most to myself—today I am convinced that we can and should present Palladio’s work first and foremost as such. Certainly at least the corpus of his domestic architecture around Vincenza! Those sober, restrained, stuccoed villas qua farms screaming their classical pedigree yet speaking a “dialect” far from Rome and Florence, to which they allude. I think today they become clearer and more powerful when seen this way. It makes them more productive and meaningful in the context of our current concerns. Ultimately, it shows convincingly that the “canon” is an ever changing, layered, and shifting body of models and ideals. Seen this way, Palladio’s work moves quickly from being marginal to becoming central to “the canon,” not only in Italy but all over Europe and eventually North America. This way of seeing is, really, the indelible mark that this “position”—physical, historical, cultural—left in my persona and the perspective from which I look at the world. And today it explains to me—even if it’s too late for my mother of Tuscan origins to understand!—why I became so enchanted and involved with Sicilian architecture and its intensely hybrid and exuberant artistic pedigree.per·spec·tive | pərˈspektiv | noun 1. the art of drawing solid objects on a two-dimensional surface so as to give the correct impression of their height, width, depth, and position in relation to each other when viewed from a particular point 2. particular attitude toward or way of regarding something; a point of view

NDA: You’re suggesting Sicily has a similar condition to that of Buenos Aires? Of being at the edge of a culturally dominant center that it is in contact with? JS: In some ways, say in relation to Rome, Florence, or Venice during classical periods, yes. Sicily is a place where this phenomenon is very much a part of the island’s cultural condition and history. When viewed from the position of dominant cultural centers, it is a culture that has been marginal to other centralities for millennia: to the Phoenicians, the ancient Greeks, the Romans, the Byzantines, the Normans, the Spanish, and so on.anamorphic | ˈˌanəˈˌmôrfik | adjective 1. denoting or relating to projection or drawing distorted by anamorphosis

So, Sicily is a place where all major cultures converged, but for which Sicily was never a particular center. And yet, when you see things from Sicily, the island prompts its own form of centrality. This duality is inevitable in Sicily. On a map, we can see it as an ineludible roadblock in the Mare Nostrum upon which all Mediterranean cultures stumbled and (accidentally) left their marks. But conversely, we can also see it as a “center” of Mediterranean culture, which collected the tolls paid by all the passersby that helped create and enrich its own particular cultural makeup. The deep layers of cultural stratification caused by this geographical, cultural condition have produced something unique in Sicily that is still palpable today.an·a·mor·pho·sis | ˌanəˈmôrfəsəs | noun 1. a distorted projection or drawing which appears normal when viewed from a particular point or with a suitable mirror or lens 2. the process by which anamorphic images are produced

Nowhere is this clearer than in Sicilian Baroque architecture, a local strain of what was otherwise a Roman cultural epiphenomenon. In Sicily, the Roman Baroque is appropriated and completely reinvented. Its exaggeration, ebullience, and luxuriance goes far beyond Rome’s, and its urban ambition is much more comprehensively realized. The architectural and urban planning experiments of the Val di Noto, as well as the codevelopment of sculpture, ornament, and stucco in Palermo has few parallels elsewhere during this time. The same can be said of the so-called “Norman architecture,” a short period in the late 11th and most of the 12th century, where an original architecture was created by the fusion and coalescence of Byzantine, Islamic, and Norman architectural streams. NDA: For how long were you actually involved with research and projects in Sicily?

JS: It was about 11 years. We would spend every moment we didn’t have to be in Boston in Sicily. And when we were in Boston, there was usually ongoing work for Sicily at the office. It was undoubtedly one of the most formative experiences of my life, professionally and intellectually. I don’t think I learned more about architecture in any other place. Sicily is a place where I understood so much about how cultures are put in motion and transformed.

NDA: In a way, your journeys to Sicily sound like the more canonical pilgrimage to Rome, but instead of offering the “definitive” references of antiquity or the Baroque, Sicily offered uniquely “derivative” ones.

JS: Well, firstly I would never call what Sicily produced a “derivative” type of work, which has a derogatory connotation. This is architecture that I would call original, fresh, and powerful. As to your other point about an alternative canonical pilgrimage, I’m not so sure about that. I knew Rome well before I went to work in Sicily. However, by the time I got to the American Academy in 1986, I had been involved in Sicily for four or five years. So at that point, it was in fact Sicily that tainted a posteriori my mature understanding of the Rome I (thought) I knew well and not the other way around.

NDA: We normally judge what is “on the edge” by contrasting it with what is at the center, with the canonical reference. I think this idea of reading things the other way around, as you are describing, is interesting. Looking back at the reference or origin point from what you’ve learned at the edge.

I guess if you think about it, it’s the only way. We are always seeing from our point of view, with all of the baggage that this implies.

JS: Absolutely. This is actually at the core of what the so-called “Western tradition” truly is, or at least, that is how I have come to understand it. I think this is the way we should always position ourselves to look at any cultural practice.

Now that I have been relieved of most of my academic responsibilities, I’ve been working on a seminar that tries to reframe what we understand by the Western tradition and leaves behind this notion of “canon,” which I don’t believe is really a solid, homogeneous ,and compact cultural phenomenon. It is an attempt to reposition my thinking around the topics that have occupied my mind as a teacher and practitioner, which has been fueled and energized with great impetus in the past year since we have all felt the need to move at another pace with sharper focus and new objectives.

My main intent is to dismantle the idea that the Western tradition is a monolithic, static, and intrinsically problematic thing, as it has become customary to describe it. While this is not a particularly original idea—scholars like Salvatore Settis have dealt with this idea at great depth already—I think we have much to gain by restating this fact. I believe we should try to further understand the ways in which this tradition is an ever changing, highly heterogeneous, macro cultural formation that has been around for thousands of years. The Western tradition is a cultural phenomenon that has had quite a few dominant strains at different times and has always been fueled, energized, and transformed by the internal dynamics of its intrinsic diversity, by the interplay of its component parts.

What I hope to achieve with the course is to take this tradition and see how once “marginal” or “dominated” component strains of its diversity have at times advanced to become dominant themselves—Palladio, again . . . For me, cases of this kind are evidence that the attempts we are undertaking to respond to today’s issues require—or better, deserve—reconsideration. I think that by repositioning our strategic intellectual perspective in order to productively work from within this collective of cultural strains—instead of taking on an approach of rejection—our capacity to amplify certain strains is much higher.

NDA: For how long were you actually involved with research and projects in Sicily?

JS: It was about 11 years. We would spend every moment we didn’t have to be in Boston in Sicily. And when we were in Boston, there was usually ongoing work for Sicily at the office. It was undoubtedly one of the most formative experiences of my life, professionally and intellectually. I don’t think I learned more about architecture in any other place. Sicily is a place where I understood so much about how cultures are put in motion and transformed.

NDA: In a way, your journeys to Sicily sound like the more canonical pilgrimage to Rome, but instead of offering the “definitive” references of antiquity or the Baroque, Sicily offered uniquely “derivative” ones.

JS: Well, firstly I would never call what Sicily produced a “derivative” type of work, which has a derogatory connotation. This is architecture that I would call original, fresh, and powerful. As to your other point about an alternative canonical pilgrimage, I’m not so sure about that. I knew Rome well before I went to work in Sicily. However, by the time I got to the American Academy in 1986, I had been involved in Sicily for four or five years. So at that point, it was in fact Sicily that tainted a posteriori my mature understanding of the Rome I (thought) I knew well and not the other way around.

NDA: We normally judge what is “on the edge” by contrasting it with what is at the center, with the canonical reference. I think this idea of reading things the other way around, as you are describing, is interesting. Looking back at the reference or origin point from what you’ve learned at the edge.

I guess if you think about it, it’s the only way. We are always seeing from our point of view, with all of the baggage that this implies.

JS: Absolutely. This is actually at the core of what the so-called “Western tradition” truly is, or at least, that is how I have come to understand it. I think this is the way we should always position ourselves to look at any cultural practice.

Now that I have been relieved of most of my academic responsibilities, I’ve been working on a seminar that tries to reframe what we understand by the Western tradition and leaves behind this notion of “canon,” which I don’t believe is really a solid, homogeneous ,and compact cultural phenomenon. It is an attempt to reposition my thinking around the topics that have occupied my mind as a teacher and practitioner, which has been fueled and energized with great impetus in the past year since we have all felt the need to move at another pace with sharper focus and new objectives.

My main intent is to dismantle the idea that the Western tradition is a monolithic, static, and intrinsically problematic thing, as it has become customary to describe it. While this is not a particularly original idea—scholars like Salvatore Settis have dealt with this idea at great depth already—I think we have much to gain by restating this fact. I believe we should try to further understand the ways in which this tradition is an ever changing, highly heterogeneous, macro cultural formation that has been around for thousands of years. The Western tradition is a cultural phenomenon that has had quite a few dominant strains at different times and has always been fueled, energized, and transformed by the internal dynamics of its intrinsic diversity, by the interplay of its component parts.

What I hope to achieve with the course is to take this tradition and see how once “marginal” or “dominated” component strains of its diversity have at times advanced to become dominant themselves—Palladio, again . . . For me, cases of this kind are evidence that the attempts we are undertaking to respond to today’s issues require—or better, deserve—reconsideration. I think that by repositioning our strategic intellectual perspective in order to productively work from within this collective of cultural strains—instead of taking on an approach of rejection—our capacity to amplify certain strains is much higher.

re·po·si·tion | ˌrēpəˈziSHən | verb 1. place in a different position 2. adjust or alter the position of

I’m actually of the opinion that going as far back as the Acropolis of Athens—two and a half millennia behind us—gives us incredible opportunities to study strains that deal with issues that are at the forefront of our concern right now, whether it’s related to identity, diversity, inclusion, or justice. In fact, the course may be called “The Acropolis of Athens and Its Consequences.” NDA: It’s exciting to think that architecture can play a role in these changing balances of power. But can it actually operate at the speed necessary for it to be proactive in these processes?

JS: I think we have to understand architecture as part of the constellation of cultural products that define a moment. In academia, we lately tend to fall under the temptation of making architecture overreach into other domains of society and culture in which other practices are more effective and powerful. But if we look at cases in a nuanced way, I believe we can see many of these forces at play in the making of architecture.

A lot of the interests I will be exploring in the seminar began developing years ago in some option studios I taught at the GSD. In the courses, we would deal directly with the profound and tense issues of cultural identity and diversity that characterize our age through many cases, including, for instance, the Indigenous Guaraní cultural territory, a place that exists at the intersection of several South American nation-states.