Danielle Allen on Government Design, the Constitution, and the Crisis of Representation

The following is Danielle Allen’s 2022 Class Day Lecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, which she delivered on May 25, 2022.

It is such a pleasure and honor to be with all of you today. It’s a miracle day: a miracle to celebrate the accomplishments we’ve just been hearing about, the miracle of the beautiful afternoon you’ve delivered to us, and the miracle of the possibility you all present. You’ve brought so much light and joy as we’ve learned about your work tackling climate change, affordable housing, machine learning. Resilience was a theme we heard again, and again, and again. You are clearly the class of resilience. And, boy, is that something we need right now.

Dean Whiting started out by asking us to remember the moment we’re in. And it is a hard moment. You all know that, and I don’t have to tell you. So, it is a responsibility for all of us to do the work of holding light and dark together, as Ralph Ellison, one of my favorite authors, once wrote. And you, as I said, have brought us so much light. It’s what we need in this world right now. I’m going to spend some time with you this afternoon proposing that above all, we need designers to take on the problems that confront us.

The gifts you have as designers are what the rest of us need to help us navigate the challenges that we face. I’m going to put to you the proposition that many of the problems in this country, specifically, are design problems. And therefore, I have come to the right place this afternoon in seeking out solutions. The problems in this country are not parochial, however. They are questions, ultimately, about human empowerment and what’s possible on our globe. You are a broad class from all over the globe.

I believe that the problems we’re wrestling with here in this country can be informative for the efforts of human beings everywhere to build that path to connection and empowerment. So, I am going to dwell on the US this afternoon. But in that spirit of seeking to open up a horizon of possibility for all of us, I want to say a little bit more about myself. I’m a philosopher and an ethicist, trying to be a politician in a certain kind of way. I’m a kid who grew up in Southern California in the ’70s, part of a huge family. My dad grew up in northern Florida with 11 brothers and sisters. Half of them sought to escape the Jim Crow South by moving to Southern California.

So we were a huge cousinage. And we were all incredibly politically committed. Almost as if with mother’s milk, we took in the lesson from W.E.B. Du Bois about democracy, about the ballot. Du Bois said, “The power of the ballot we need in sheer defense, else what shall save us from a second slavery?” Democracy is that fundamental, that much at the core of what it takes for communities to have a path to empowerment. We all dug in, and fought, and believed, but across the entirety of the political spectrum.

I remember the year that my aunt was on the ballot for Congress in the Bay Area for the far left Peace and Freedom Party. It was the same year my dad was running for Senate from Southern California as a Reagan conservative. So, boy, those were some dinner table conversations. They always agreed on the what. The what was empowerment for communities, so that those communities could build the security they need to thrive.

The disagreement was on the how. My dad—skinny, with smoke from his pipe curling around his head and bald at 20, poor guy—was making the case for market freedoms and libertarian choice as the way to empowerment. And my aunt—Mack truck, big belly laugh—was making the case for investment in productivity across all the sectors of our society and community. They went at it; but never breaking the bonds of love, never breaking the bonds of mutual respect, that commitment to each other as human beings.

That’s the lesson I took from my childhood about what democracy can give. That space for contests, to have those hard fights, and to try to find that path to empowerment for everybody. I grew up having a sense of our country and our world as being a mix of light and dark. I could see the accomplishments of the country. I could see the opportunity it delivered. I could see the potential. I could see our failings and our errors for sure.

Over the course of my lifetime, we have lived through some extraordinary things in this country. A half century of time. In that time, we’ve had what I call “the great pulling apart.” There’s a massive increase in income and wealth inequality. To the point that we’re at the same place that we were in 1929 before the Great Depression. It is the period of time where we have seen the massive rise in incarceration that has trapped communities of color, and some of the worst things imaginable for any young person coming into the world on our planet. It is also a period of time where we have seen polarization and the acceleration of climate crisis. And now, this remarkable thing we’re living through, where we’ve moved from a period of globalization to a period of deglobalization. A period of great pulling apart. My own family has experienced that pulling apart. Some of us got lifted up on elevators of opportunity to positions of the greatest privilege the world has to offer.

There is no greater privilege than being a tenured professor at Harvard University. Jeff Bezos could forget it. Billionaires can forget it. I mean it: there is no greater position of privilege. And those of us who have the chance to be here owe the world so much. But, at the same time, some of my cousins have gotten trapped and pulled into the worst the world has to offer. I’ve lost a younger cousin by the same name, Danielle, to substance use, and opioid substance disorder. I have lost another cousin, not dead, but broken by a police beating in a case of mistaken identity. The person they were looking for shouldn’t have been beaten like that, and my cousin definitely shouldn’t have been beaten like that. But for me, the real turning point moment—the moment where I went from having a mixed light and dark sense of our world to having a pretty dark sense of our world—came in 2009, when I lost my baby cousin, my youngest cousin, Michael.

Michael was probably the first baby I ever held when he was born in 1979. I was a lonely kid being bullied on the school playground that year. And then my aunt delivered a ready-made new best friend. He was a beautiful kid, full of curiosity, with a bright smile and a lively mind. He wanted to grow up, and travel the world, and learn French. Instead of that, in 1995, when I was a couple of years out of college, he was arrested in Southern California on a first arrest for an attempted carjacking.

This is a terrible thing to have done. It was also a time in California where punishment was at its most intense. On that first arrest, at the age of 15, Michael was sentenced to 12 years and 8 months. When he got out after 12 years, I was what I call “cousin on duty.” I tried to put the pieces back together again by helping with housing, and school, and jobs. Michael had two years out, two years of freedom—that treasure—when he was shot and killed by somebody he had met while he was in prison.

It’s a hard story to hear—I know that. Especially on a miracle day like today. And it’s a hard story to tell. But I tell that story because that was the point for me, that turning point moment, where I started to dig into the question of how in this country, we could steer our institutions to achieve the kinds of reforms that would open up opportunity for communities of all kinds, put a foundation for flourishing back underneath everybody. And the truth is, I got more and more frustrated as our politics also got more and more complicated, and more and more polarized, and more and more difficult.

So now I come to that design problem that I promised I was going to share with you. It’s the reason we need you and your great gifts at this hard moment in time. Why is it exactly that things are so crazy, so complicated, so messy in this country right now? The short answer is that Facebook broke democracy. They didn’t mean to. It was definitely an accident. But they definitely did.

Now, I want to explain that. What do I mean exactly? The fact of the matter is that when this country was founded, it was an experiment in design. The problem that the country faced in the 1780s was that they could not get a functioning banking system. They could not pass a budget in Congress. They did not have a quorum in Congress. They could not make decisions. It was a broken thing, a set of machinery that didn’t work.

Out of that moment and problem came the Constitutional Convention. It was a design solution to the problem of a community of people who could not actually get anything done together. And in that moment when they designed that Constitution, they had all kinds of problems of tribalism, and factionalism, and division—just as we do now. This was, in fact, one of their greatest concerns. So, the Constitution was literally a design solution to the problem of faction, and division, and polarization.

Let’s dig into the nature of that design and how it was supposed to solve that problem. The answer, the solution, the design is described in detail by James Madison, one of the authors of the Constitution, in an essay called “Federalist Paper Number 10.” The Federalist Papers were a series of essays published in the newspaper to defend the new Constitution. And in that 10th essay, Madison takes the time to explain how this design is supposed to address the problem of faction.

We teach this essay to undergrads in a variety of courses. And we typically teach the design solution as one where a broad republic was supposed to solve the problem. But when we teach this paper, we usually just focus on the word republic. The basic argument made is that a republic is a structure of government with representatives. People get elected to serve. And it’s the job of the representatives to synthesize, and moderate, and deliberate, and bring together to find a solution for hard political problems.

We forget to teach the part of the design solution that is captured by the word broad. And that word was actually a proxy word for geographic dispersal. Madison was very clear that one of the things he expected to see in a country that was spread out across a continent separated by rivers and mountains was that people with extreme views would not be able to find each other. This was a premise.

The idea was that because of geographic dispersal, in order to get your views into the public sphere, you would have to go through a representative. Geography was a forcing factor to make a system of representative government work. But that part just doesn’t exist anymore. An actual premise undergirding the design of the Constitution was knocked out by social media. That’s what I mean when I say that Facebook broke democracy.

What that means is that we have a very significant design problem facing us right now in any country that wants to organize a structure of self-government. We have a crisis of representation. And I want to just drive home how impactful that crisis is by calling your attention to a funny feature of our political landscape in this country. If you look at our national politics, we look exceptionally divided. We look like we are at each other’s throats all the time.

But if you change your attention, if you look elsewhere, if you look at state politics and ballot propositions, you see a different America. In Florida, a supermajority of people voted to re-enfranchise, to return the right to vote, to people who had completed their felony conviction. By supermajority, I mean more than two-thirds of the electorate, so Republicans as well as Democrats. In Mississippi, in 2020, more than 70 percent of the people voted in a new state flag, getting rid of the old emblems of the Confederacy, and adding forward-facing symbols.

Here in Massachusetts, 75 percent of us voted for the Right to Repair ballot proposition, which gives small auto dealers and auto shops access to the data in cars, giving them the chance to compete against big auto manufacturers. Three different states, three very different contexts, and American people standing up for inclusion and fairness, sticking up for the person getting the short end of the stick. You wouldn’t know that from our national politics.

That’s where the crisis of representation comes in. There’s a disconnection between our representatives and what’s actually happening in terms of what people are willing to do in our states at a more local level. That’s the design problem that we have to address. There are solutions out there in the political landscape. For example, ranked-choice voting is a good one. It requires candidates to try to build actual majority coalitions, instead of just carving off minority portions of the vote that lets people with more extreme views get through. That’s a political solution.

And we need those. But I believe we also need a whole host of other solutions. I was hearing you talk about some of them, listening to those prizes listed. We need public spaces where people can see themselves together and with one another again. The work on affordable housing is critical, because at the moment, we are letting our society just segment into class-separated ways of living and being. And we will not find our way back to solutions with those divisions.

Some of you have been working on Big Tech and machine learning. And we have to figure out how to design these tools—which are now the infrastructure of our information ecosystem—in ways that are actually good for us. But above all, my experience of working with designers is that you believe in the power of communities to articulate their needs and to participate in the design process.

I think that is a skill you’ve been taught throughout your classes during your time here. It’s not taught everywhere. Lots of times, people and institutions will try to deliver solutions in a top-down way. And if we are going to design our way out of the problems that we have right now, we really need your skills. We need you to lead us in engaging big, cross-cutting communities in participatory processes to get us to a goal that supports a healthy society. So, it is a hard time.

I just told you the story in my own life of the point at which for me dark started to outstrip light. But I have to admit, I’m a commencement junkie. I love commencements because this is where hope is. And again, I heard it with such power, and force, and clarity in the descriptions of your work. So it is an honor to be with you and with your work. We will be both resilient and OK. So thank you.

–––

Danielle Allen is a professor of public policy, politics, and ethics at Harvard University, and James Bryant Conant University Professor, one of Harvard’s highest honors. She is also a seasoned nonprofit leader, democracy advocate, national voice on pandemic response, distinguished author, and mom. Danielle’s work to make the world better for young people has taken her from teaching college and leading a $60 million university division to driving change at the helm of a $6 billion foundation, writing for the Washington Post, advocating for cannabis legalization, democracy reform, and civic education, and most recently, to running for governor of Massachusetts. During the height of COVID in 2020, Danielle’s leadership in rallying coalitions and building solutions resulted in the country’s first-ever Roadmap to Pandemic Resilience; her policies were adopted in federal legislation and a Biden executive order. Danielle made history as the first Black woman ever to run for statewide office in Massachusetts. She continues to advocate for democracy reform to create greater voice and access in our democracy, and drive progress towards a new social contract that serves and includes us all.

Students in Dialogue

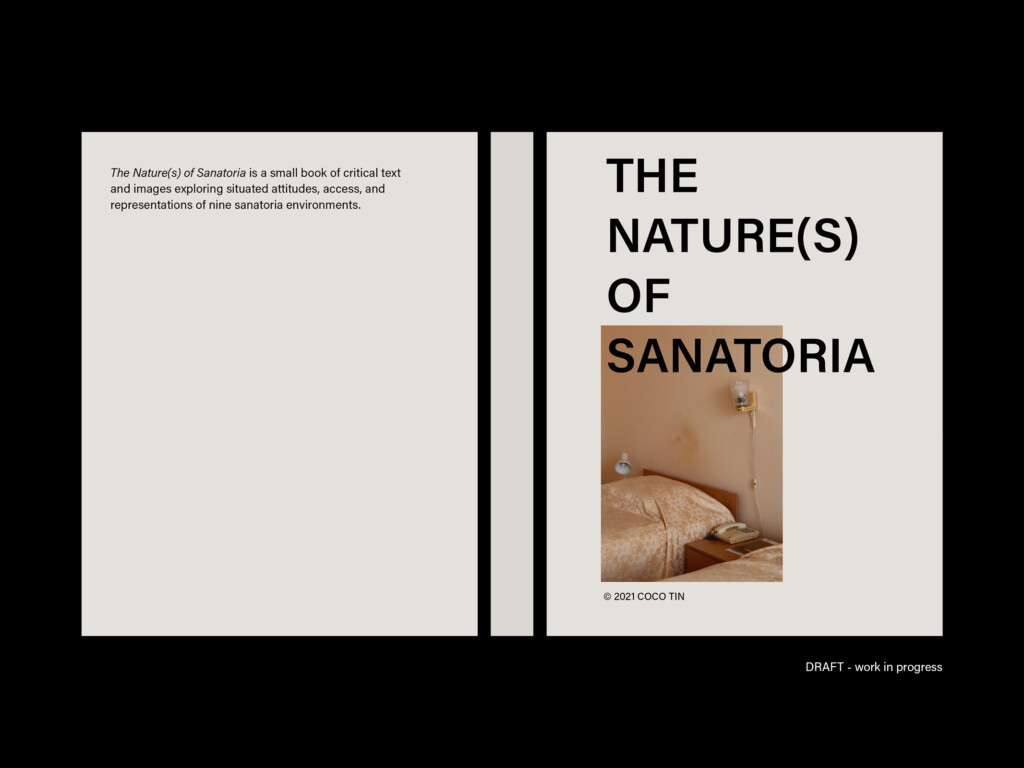

What’s it like to be a Master in Design Studies (MDes) student in the Narratives domain at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD)? In this series of candid conversations between students, Ian Erickson (Master in Architecture I ’25) speaks with CoCo Tin (MDes ’23) about merging research and design and her forthcoming book based on research supported by a Kohn Pedersen Fox Traveling Fellowship.

Ian Erickson: What ideas are most interesting to you right now?

CoCo Tin: Ideas of fluidity, gender, and East-West encounters have been on my mind lately.

What were you doing before you came to the GSD?

I graduated from Cornell in 2019 and worked for the architecture firms Food New York and Collective in Hong Kong. While at Collective, I continued my Kohn Pedersen Fox (KPF) Traveling Fellowship that began by visiting still functioning sanatoriums, compiling the body of research into a full-on publication. I cold emailed a bunch of publishers and got positive responses. So by April 2021, I had written a full manuscript first draft (56,000 words!). It was a productive balance of part-time design work paired with self-directed research.

What led to your decision to attend the GSD?

Having a Bachelor of Architecture (B.Arch) from Cornell means I spent five years going through rigorous design studios. Yet I always had an itch for history/theory that I never really got to prioritize. So the newly restructured Narratives domain of the MDes program stood out to me. In finding myself working part-time between designing buildings and doing research, I discovered that it was a limbo space I really enjoyed. I decided to get a formal master’s education in the history and theory side of architecture.

Was there a particular part of the program that made you want to attend the GSD specifically?

To be honest, I think it was Erika Naginski because she is so organized, articulate, and generous with her scholarship. Also, the program being two years long was appealing; it felt like the perfect amount of time to build on my sanatoria research work and enough to start something new. Also, the Womxn in Design’s Bib: An Annotated Bibliography on Identity Theories stood out. I was—and still am—craving a more ecofeminist approach to architectural history and theory.

Do you have any advice for preparing a portfolio and showcasing your work in order to apply to MDes?

I would say put your wackiest project first. The optional supplementary portfolio submission for Narratives was a writing sample. But in my portfolio, I also submitted a lot of design work because writing and visual thinking go hand in hand in my process. I think the program shares that sentiment since “Word and Image as Narrative Structure” is the title of the required proseminar course for the Narrative program.

What are some of your goals for after graduate school, and how do you feel the MDes program has prepared you to accomplish them?

To finish and officially publish my book! But even after one semester here, I’ve realized how much my thoughts have developed. For example, for the Ecologies proseminar with Chris Reed, I had the chance to rework the frame of my book and produce new writing with a more environmental focus. Rather than just seeing the building as a cure or as a space of care, I explored the sanatoria effect as closing the gap between the built and “natural” environment. My time in MDes has given me the tools to dissolve the nature-culture binary at large into a more complex and nuanced discussion.

That aside, I came in thinking that a PhD would be the next goal, but now I’m not so sure if that’s the immediate step post-GSD. As I mentioned, I want to stay in this limbo of design and research, so right now I’m exploring design at large. For example, this summer I’ve pivoted slightly and am working in creative strategy for spatial projects at 2×4. What remains strong is a deep desire—paraphrasing Lydia Pang—“to make the world a little less shit.” A natural step for this goal seems to be teaching. I’ve been lucky to be TA for MArch I’s Core II studio, and also for history/theory seminars. Doing that in tandem with RA work for Jeannette Kuo and the wide range of classes at Harvard and MIT has broadened my horizons in terms of applying spatial or architectural thinking across many projects with a social-environmental agenda: my aim is to go beyond the building. I think this sort of freedom for exploration has instilled a desire for some sort of creative professional and teaching practice before pursuing a PhD.

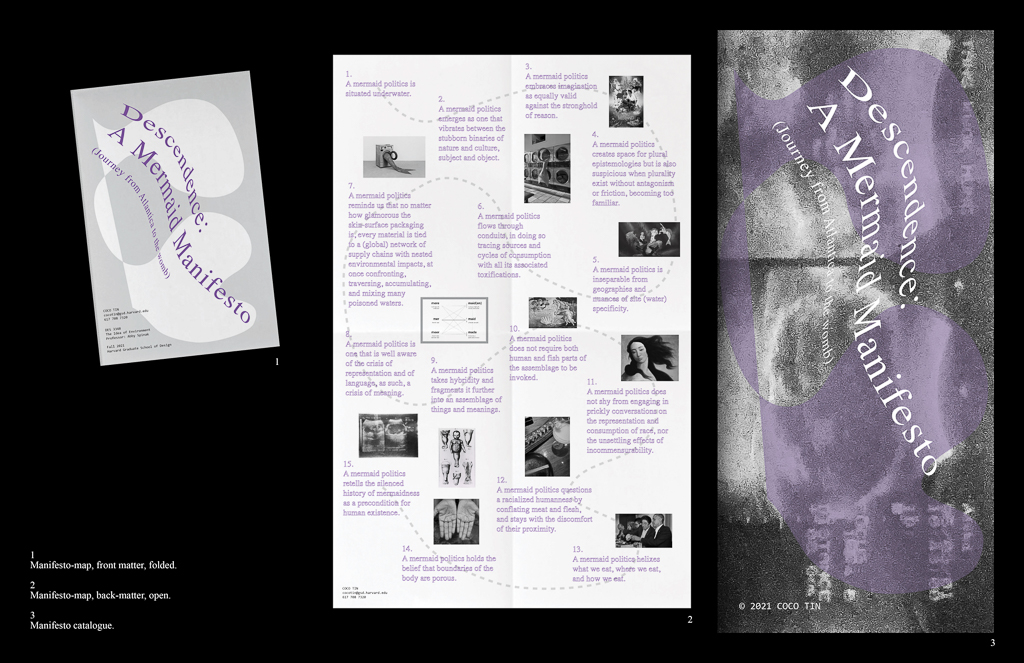

You taught a J-Term course (one of the GSD’s student-taught winter break term classes). What was it about?

My J-Term course, “Mermaids: An Amphibian Story,” built upon a radical archive (Descendence: A Mermaid Manifesto . . . Journey from Atlantica to the Womb) for Abby Spinak’s “The Idea of Environment” class. It was about mermaids and how thinking through this mystical and fluid creature can challenge the porousness of boundaries in our bodies and the environments that we occupy. Of course, the mermaid fascination is also a bit cheeky; it pushes back against the “male model figures”—e.g., Vitruvian Man, Modulor man—and their stronghold as the standard bodies for design. The work of Stacy Alaimo and Donna Haraway was crucial to my thinking. Mermaids are interesting because they emerge in almost every culture’s origin story but have been domesticated by Disney. For example, the legend ancestors of Hong Kong are the LoTing Fish (盧亭). They are half man and half fish, but not the usual hybridity that we imagine when we reference mermaids. So in a sense, mermaid-ness is also a way to spatialize the ontology of being hybrid. What does it mean to be inter-species and environments?

Do you have a favorite course? What has been exciting or challenging in your coursework?

The Narratives proseminar is still one of my favorites. I was skeptical at first, because we were reading Kant, Derrida, and other canonical grad school figures that are challenging to read, and don’t really discuss things like gender. But Erika set it up in a way where thinkers would be almost pitted against each other. The proseminar was structured so well as a methodology course that, to this day, things like Peirce’s triadic semiotics, or the study of signs, are foundational to my ongoing work.

Abby Spinak’s “The Idea of Environment” and a class at MIT in the Art, Culture, and Technology (ACT) program with the artist Judith Barry were both refreshing for their wide range of new philosophical and visual references.

Students in Dialogue

What is it like to be a Master in Architecture II (MArch II) student at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD)? In this series of candid conversations between students, Ian Erickson (MArch I ’25) speaks with Dutra Brown (MArch II ’22) about working on commissioned built projects while still a student, her decision to come to the GSD, and her post-graduation goals.

Ian Erickson: What ideas are most interesting to you right now?

Dutra Brown: I’ve been thinking a lot about embodied forms of knowledge. This past semester, “The House: A Machine, Queer and Simple”—the option studio co-taught by Andrew Holder—participated in movement workshops led by the artists Gerard and Kelly, who also co-taught the studio. The workshops informed our architecture projects by giving us an alternative way of thinking about how we as designers articulate and define space.

What were you doing before you came to the GSD?

I was living in Los Angeles and getting my bachelor of architecture from the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc). The summer leading up to the start of the fall semester at the GSD I was working on a design-build pop-up for a wellness retail company called Flamingo Estate in Los Angeles. I was actually only able to do the project because school was remote, and so I was able to stay in Los Angeles and see the build-out through. I completed the project with a collaborator, ceramics artist Alex Reed, who also needed to be close to the project, as we were fabricating a lot of bespoke ceramic tiles. It was the first design project that I did under my own name that got built in real life, and it was incredibly rewarding to watch unfold while I was balancing the academic work of the first semester of graduate school.

What led to your decision to come to the GSD specifically?

I actually did the GSD’s career discovery program in 2013 after my freshman year at NYU, where I was undeclared. I loved it so much that I immediately transferred into an architecture program for the remainder of college. Given that attending the summer program was a huge turning point in my life and education, I really wanted to apply to attend the GSD for a full degree program. Also, the faculty here are very engaged in their own built practices, which I wanted to learn from. The vibrancy with which the GSD approaches building was very exciting to me and also distinct from my undergrad degree, where I was working on a lot of speculative projects. So, for me, it was also an attempt to jump outside of my comfort zone.

Did you have a favorite course at the GSD?

My favorite course was my most recent studio with Toshiko Mori, “Between Wilderness and Civilization.” The studio brief was to design your own program for Monson, Maine, an aging rural town that currently has 600 residents and a lot of job loss due to the recent closure of a paper mill and furniture manufacturing company. The Libra Foundation is investing in the town’s future by calling for proposals to construct an innovation lab in a 72-acre abandoned farm located right outside of town. We had a lot of conversations with people who lived in Monson and other stakeholders, and it became almost like a thesis, where you have to choose your program and understand the social, political, and economic implications of the program that you’re choosing. It made me realize there is all this work that you have to do before you even touch design.

How have you grown through your graduate studies at the GSD?

I think becoming more aware of how design intentions are read by communities outside of the design field has been formative for me.

What are your next steps now that you’ve graduated?

This summer I’m working to finish up the design of an ongoing interior renovation project for two guest cabins. The project makes use of some recycled material from the pop-up that I was talking about previously; so the first thing I worked on when I started at the GSD is also going to be the thing that brackets the end of my time here. Hopefully by the end of next summer we will break ground on construction. It’s really fulfilling to be able to take what I have learned about design and building during grad school and immediately apply it to real-world projects.

Editor’s Note: This conversation was conducted in Spring 2022. Dutra Brown graduated with the class of 2022 and is now based in Los Angeles.

Students in Dialogue: A Conversation with Maximilian Mueller

What is it like to be a Master in Design Engineering (MDE) student at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) and the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences ? In this conversation, Ian Erickson (MArch I ’24) speaks with Maximilian Mueller (MDE ’22) about his background in neuroscience and music production, taking classes across the university, and working on a forthcoming PlayStation video game.

Ian Erickson: What ideas are most interesting to you right now?

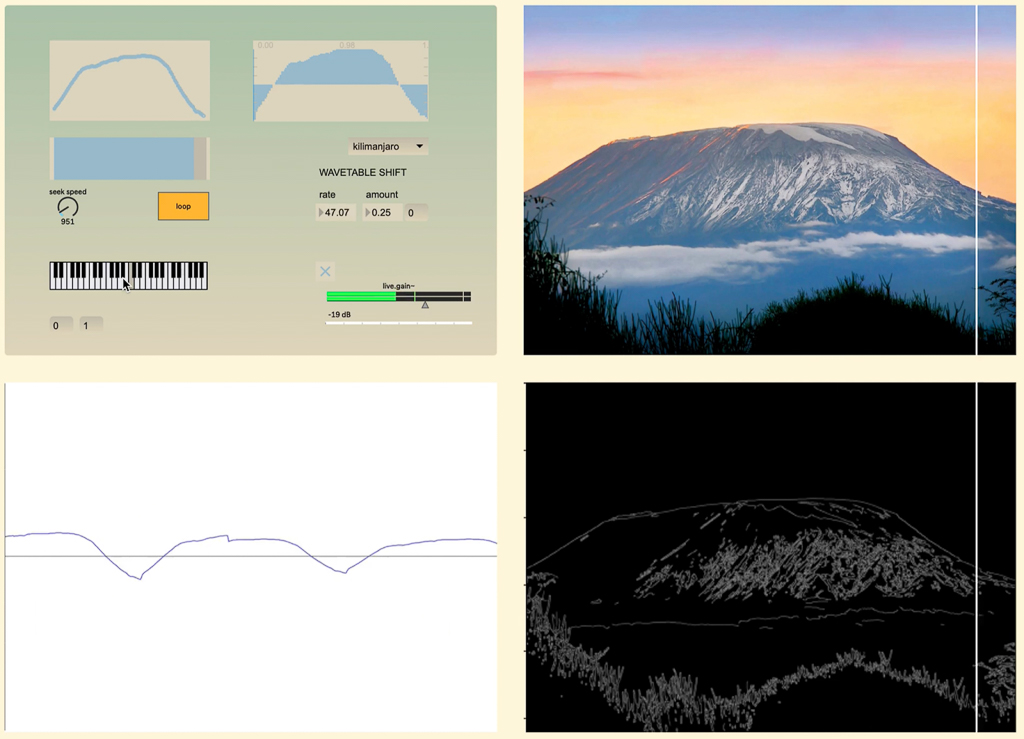

Maximilian Mueller: Lately I’ve been thinking about the ways our mediasphere is moving towards including more deliberately mutable digital works. For instance, an MP3 that constantly evolves based on some latent intent of its author or in response to its context, rather than simply being a static digital file like we are used to.

What were you doing before you came to the MDE program?

My academic background is in neuroscience and my past work ranges from zebrafish teratology to music production, data mining, and behavioral health. Most recently, I’ve been focused on music—writing for commercials, TV, and other artists.

And what led to your decision to attend the MDE program?

I wanted to integrate and formalize disparate interests such that my creative and professional practices could merge in a productive and economically viable way. Harvard University, and specifically the MDE program, which is housed between two separate and exciting schools—the Graduate School of Design and the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences—seemed like the ideal place to do that.

Can you reflect on how you’ve grown so far through your graduate studies and what you’re looking forward to in the remaining time you have here?

Just being at an institution like this is eye-opening in so many ways. You are exposed to so many new ideas and people; I’m still parsing what it all means! I’m particularly grateful to have met the people at metaLAB—I’m currently working on sonic interface design for their Curatorial A(i)gents project, to be exhibited next year in the Harvard Art Museums ’ Lightbox Gallery.

As I near the end of my time here, I’m looking forward to pushing the integration of arts/design/engineering as far as it can go, both through my thesis and through the video game I’m working on.

I’m really excited to hear more about the game!

The game is called Nour: Play With Your Food, out of an indie studio called Terrifying Jellyfish, published by Panic, and out on PlayStation later this year. It’s an art game that explores food aesthetics, culture, and memory through free-form play. It asks whether virtual food can look so good that you can taste it. Can visuals and sound alone evoke the sensation of hunger?

I was initially brought on to do the soundtrack. Coming in, I had no game development experience and I am not much of a gamer, so I didn’t really know what I was getting myself into. Yet, it quickly became apparent to me that a static soundtrack wouldn’t do—it had to be generative and integrated into gameplay mechanics. In this way, the game functions as an instrument that anyone can play: conjure food and make a melody, create a dish and make a song. Gameplay has some immediate and structural sonic consequences; the soundtrack is created in real time, based on the nature of player behavior. Music in Nour acts not just as a soundtrack, but as an interface. Players can exert influence over the scene and its contents in both familiar and new modes of musical gameplay, using rhythm, pitch, and volume as a language of sorts. A lot of thought went into making the sonic interface accessible to a first-time player yet rewarding to someone that’s “mastered” the instrument.

Being invited to write some music spiraled into a heuristic exploration of this incredibly rich medium. My coursework during the first year of MDE prepared me to come into a new discipline cold, use my design thinking skills to imagine something novel in that arena, and apply my growing technical skills to make it happen.

Can you tell me about a favorite course you’ve taken at the GSD?

One of my favorites was an MDE core class called “Integrative Frameworks,” taught by Professor Woodward Yang. I’d describe it as a polymathematics seminar. We did a few hundred pages of reading a week on subjects ranging from universal design to IP law, political economy, and physics. We would then analyze and discuss the modes of thought and the structures supporting the ideas, with the goal of integrating other frameworks.

How is the MDE thesis structured and what are you working on for it?

The MDE capstone or IDEP (Independent Design Engineering Project) is a year-long thesis focused on systems-level interventions. For my IDEP, I developed an aural AR framework that grants people new senses and enables media to react to a user’s context in real time.

Can you speak a little bit about your experiences taking courses outside of the GSD?

Given the dizzying array of wonderful classes at Harvard, it’s a challenge to decide on (and then lobby for) the perfect course. I’ve taken quite a few outside the GSD and would say that generally GSD students’ design perspective is valued highly in non-GSD classrooms. What is second nature in Gund is not elsewhere. The same goes for the perspectives and frameworks of the host schools when their students take courses at the GSD. It’s that collision and integration of frameworks that I love most about my time here.

Editor’s Note: This conversation was conducted in Spring 2022. Maximilian Mueller graduated with the class of 2022.

OFFICE on the United States flag and American Architecture (Model)

As midterm elections approach in November across the United States and citizens exercise the right to vote, OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen offer the following statement on the image of the flag that is included in American Architecture (Model), on view on the front patio of Gund Hall until April 2023.

Atop the pavilion stand three objects: a model of a technical box, a model of a solar panel, and a model of a flag. Together they stand as symbols of architecture. The simple structure of the pavilion foregrounds these technological and emblematic features as pure signifiers, emphasizing architecture’s representational dimension. But whereas the solar panel is a literal symbol of the urgent necessity to address climate change, the image of the United States flag provokes diverse interpretations and demands explanation.

The flag is a poignant symbol saturated with manifold meanings, any one of which may be true for those encountering it—not only within the United States, but also around the world, where nearly anyone who is confronted by the flag has been affected by some form of American hegemony. The flag epitomizes a fundamental contradiction central to the United States’ origin story—the way in which democratic values are and have been simultaneously extended and ruthlessly denied. Over the course of its political history, the flag has been claimed by both the right and left. It has stood as a symbol of liberation and colonization, war making and peace keeping. It has been taken up by abolitionist and pro-slavery causes, and has been championed by immigrants and nativists alike. Most recently, the flag has been embraced by demagogic populist and white nationalist movements, prompting liberals and progressives to distance themselves from it. Overall, it is important to acknowledge that through time the flag has served as the ultimate symbol of shifting, if not conflicting national values.

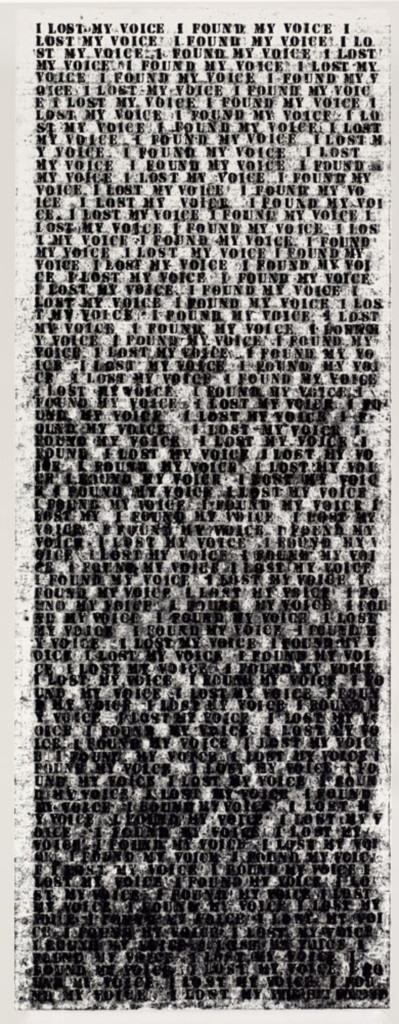

In the United States, the national flag is given a prominence rarely seen in other countries. It adorns government buildings and single-family homes. It hangs in airports and schools, and above the statue of John Harvard in Harvard Yard. As a commonplace object, it has been appropriated by consumerist culture and transformed into a pop symbol. It has also served as a means of exposing longstanding histories of violence, racism, and sexism, in works ranging anywhere from The Simpsons to works by visual artists including Jasper Johns, Cady Noland, Tseng Kwong Chi, David Hammons, Barbara Kruger, Gordon Parks, and Ed Ruscha.

The flag atop the pavilion is not intended as a real flag. It is an image of a flag printed on vinyl, as a billboard. Detached from its political context and aestheticized as an artwork or architectural ornament, we hope it sustains reinterpretation as a readymade, one that recalls the flag while creating critical distance and space for discussion and reflection in its abstraction. The pavilion was envisaged as a public space available for everyone’s use, as a place for debate and encounter, politics and culture, education and humanism, and most importantly one of embrace of the diversity of the Harvard community. We should not be naïve, however, and ignore the multitude of visceral and critical responses the image of the flag provokes. On the contrary, we hope to acknowledge and provide an opening for scrutiny of the flag’s symbolism, grounded in the perspectives and experiences of those who encounter it.

How an urban design studio is proposing a more equitable approach to Boston’s building boom

Over the past decade, the Boston/Cambridge area has attracted tremendous attention and investment as a global center for technology innovation. Major hospitals and research institutions (so-called “meds and eds”) have been the driving forces behind innovation and enterprise districts arising across the city, including Kendall Square, the Seaport, and the planned Harvard Allston Enterprise Research campus. Across the United States and globally, these districts represent a relatively recent product of the market, an urban typology that’s not yet well established. To Andrea Leers, design critic in the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Urban Planning and Design department, this kind of development is a double-edged sword. She explains, “It’s powerful, and it’s bringing jobs and economic benefit of all kinds, but it is also a kind of community killer because it’s frequently a mono-use and fairly exclusive development type.”

This spring, Leers’s Urban Design studio, “Leveraging Boston’s Building Boom to Advance Equity” (taught with Associate Instructor Anthony Averbeck), took on a real site as a case study in proposing a more vibrant, inclusive, and welcoming type of innovation district in Boston. “The task that we set for ourselves was how to build on the energy and initiative of this burst of economic investment to build more than a cluster of lab buildings and associated facilities, but something that could really benefit and connect with the adjacent neighborhoods to bring a sense of equity—not an island of privilege—to this site,” she says.

Harvard has an obligation to lend its creativity and research to making its home city as wonderful as it can be, to take part in its community, and to contribute,” Leers points out. “I think that there was real value in having a serious look at Boston itself.

Andrea Leers

With its proximity to Moakley Park and Carson Beach to the north, Dorchester Bay to the east, a housing development and the institutional campuses of UMass Boston and the JFK Library to the south, and the diverse neighborhood of Dorchester to the west, the site is ideally located, but plagued by accessibility challenges. “The site is well served by transit and by car, but made an island effectively by the elevated highways, train lines, and massive traffic circles,” Leers says. “It’s a great site that’s impossible to get to.”

This underdeveloped land, currently a 1,300-space parking lot for UMass students that was formerly a convention center and shopping mall, is a blank slate for a porous new district that can leverage public transit to link nearby communities with economic opportunity through jobs, services, stores, the waterfront, and the city beyond. “[The students] really enjoyed tackling a real site that they could go to visit,” Leers says. “They could walk through the adjacent neighborhoods and get a feel for the place, and then begin to imagine things on it.”

Students undertook an initial hands-on research and analysis phase before diving into the development of their studio projects. Physical engagement with the site, research, and guest lectures from the Dorchester community, UMass leadership, and GSD faculty enriched the students’ understanding of the area’s topography, history, and demography, and helped them identify the unique possibilities and challenges that informed their design strategy. Students also looked at global approaches to innovation districts and other waterfront development precedents to analyze programmatic needs and opportunities specific to the Dorchester site.

Building upon this shared research and analysis, students split into teams to develop and test their design concepts. Through drawings, physical models, and building studies, the students engaged issues of urban form, circulation, and open space, exploring the specific qualities that make a place vibrant but also useful and inclusive to a diverse range of constituents.

Dorchester Innovation Commons,” designed by Pinyang Chen (MAUD ’22) and Zhuoer Mu (MAUD ’22), features a chevron-shaped development, with a network of streets and buildings widening to either side of a central green. The intent was to draw people from the transit hub down through the district to the waterfront park, via this porous central promenade.

In “Pathways to Prosperity,” a model designed by Danny Kolosta (MUP ’22) and Adriana Lasso-Harrier (MUP ’22), research and interviews with Boston educational and vocational experts inspired the inclusion of three on-site spaces—the Nonprofit Exchange, the Adult Success Navigator, and the Youth Excelerator—that create job training and educational opportunities to help residents gain access to the innovation economy.

“Greenway to the Bay: A Stroll Through the Neighborhood,” a model developed by Dianne Lê (MLA ’22 and Danny Kolosta (MUP ’22), organizes the site through the landscape, anchored by a new diagonal greenway that connects the site and adjacent neighborhoods to the harbor.

The “Well-Tempered Grid” by Saad Boujane (MAUD ’23) and Naksha Satish (MAUD ’22) proposes an urban fabric that reconciles the different street networks and land uses surrounding the site. Disrupting the new grid are strategically placed and distinct blocks of buildings that respond to the adjacent conditions: a gateway node housing biotech and pharmaceutical labs, a learning commons interfacing with the residential neighborhood, and an eco-innovation hub on the waterfront.

The students’ concepts for the Dorchester Bay site present varied approaches to density, building scale, programming, and urban frameworks; but the exercise yielded critical learnings that were shared across the board. Innovation districts are a recent phenomenon, and a typology that’s not yet well defined—there’s no standard that can serve all sites. They discovered that a coherent blend of street networks, open spaces, access to the water, and inviting places to go matter more than the density and composition of buildings.

“Going in, we were really concerned with what was it going to be like to have so much building in this place where there wasn’t any and nothing like it nearby,” recalls Leers. “And in fact, that turned out not to be the key question. It was really interesting to learn the importance of just making it a normal piece of city.” Critically, integration of programmatic anchors that engage the community—whether training or education facilities, spaces for family recreation, childcare centers, and neighborhood retail—are crucial to making innovation districts more inclusive to and integrated with their neighbors.

“Plains and Pampa: Decolonizing ‘America,’” by Ana María León Crespo—Excerpt from Harvard Design Magazine

It is a common trope for scholars from South America, Central America, and the Caribbean to argue that America is the continent, and not the country. It is less common to consider what the idea of America as a territorial unit might imply. Thinking about the region as a whole prompts us to notice similar processes and shared politics, particularly in reference to decolonization and decolonial discourses.[1]

Indigenous scholars in settler colonial countries such as Australia, Canada, and the United States have advanced theories of decolonization as the rematriation of Indigenous land and life. [2] In contrast, Latin American decolonial theorists—known as the Modernity/Coloniality group—have focused their critique on the role of colonialism in the construction of modernity.[3] Both terms stem from the discourse on resistance and struggle by Martinique intellectuals Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon, whose argument cuts across these groups and highlights the role of Black studies within both—a complicated intersection that I’m unable to address in this piece. [4]

Given the increased use of these terms, it is important to understand the slippage between decolonization and decoloniality, which have in many cases been conflated. More urgently, both concepts have often been reduced to apolitical notions of increased geographical coverage, eloquently summarized by Anni Ankitha Pullagura as the notion of “making empire more inclusive.”[5] Rather than cede ground to this depoliticized inclusion, the challenge in thinking through the idea of decolonizing “America”—or any territory for that matter—is that of centering the voices excluded by empire. Land and its inhabitation, occupation, or possession plays a key role in this conversation. The way we situate ourselves within it has the potential to redefine the history of architecture as well as architecture itself.

Decolonization points to the impact of settler colonialism—a type of colonialism in which the Indigenous population is replaced by an invasive settler society. Meanwhile, decoloniality is less geographically determined, and seeks to critique colonialism as an epistemic framework whose violence is present in all locations, even in colonizer regions. In doing so, decolonial theory can sometimes place too much emphasis on Eurocentrism, eliding the internal conflicts highlighted by what decolonization theory describes as the “entangled triad structure of settler-native-slave.” [6]

Thinking through this structure, decolonization points to the multiple ways in which the development of settler colonialism—in countries such as the United States but also, I argue, Argentina—is enmeshed in processes of capital extraction that have racialized populations and depleted the land. Complementing this discourse, decoloniality reveals the ways in which these processes are constitutive of modernity itself, understanding the European arrival to America as a component of the acceleration of global commerce that links modernization, capitalism, and empire.

A brief example highlights how comparing these different histories through these combined theoretical frameworks can reveal some blind spots. The independence movements in both the US and Argentina were led by European descendants eager for political independence from Europe and more economic power. While in other countries Indigeneity was strategically appropriated in the formation of national identity (particularly in countries with monumental Indigenous architecture, such as Mexico and Peru), in settler colonial societies Indigenous peoples were seen as a threat to the construction of the nation.[7] Thus upon gaining independence, both the US and Argentina targeted the Indigenous populations that inhabited what they conceived as their land, resulting in a series of extermination campaigns with the specific objective of appropriating Indigenous territory.

Human and non-human agents have inhabited the continent for millennia, benefitting from mutually sustaining relationships. The aggressive hunting of the bison in the US, and the introduction of non-Indigenous species such as cattle and swine in both countries, radically transformed this landscape.[8] The replacement of local staples with more profitable, non-Indigenous crops echoes the aggressive replacement of Indigenous people including Anishinaabe groups in the north and Mapuche, Aymara, and other groups in the south. Taken together, these are the processes of settler capitalism, the primary goal of which is the transformation of land into a site of extraction. The role of the US Plains and the Argentinian pampas in the construction of these countries’ national identities highlights how the mythification of the land is a component of its commodification. These and subsequent histories of land dispossession, occupation, extraction, and capital constitute our American modernity.

Decolonization points to the status of America as occupied land, and decoloniality reveals the role of this occupation in the production of modernity. Understanding the intersection between the two allows us to turn toward new relationships with the land—relationships that might dismantle settler frameworks and center previously silenced voices. While decolonization and decoloniality have different, overlapping definitions, it is their shared politics that suggest a different approach to land and its history. Nick Estes, historian and citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe, titled his groundbreaking book on Indigenous resistance with the beautiful words Our History Is the Future. [9] Indeed, the histories we learn, research, and teach open up other futures. By studying the environments that peel away settler narratives of buildings and landscapes, we can open the way toward decolonized and decolonial futures.

Ana María León Crespo is an architect and a historian of objects, buildings, and landscapes. Her work traces how spatial politics shape the modernity and coloniality of the Americas. León teaches at the Harvard GSD and is cofounder of several collaborations laboring to broaden the reach of architectural history.

[1] The Decolonizing Pedagogies Workshop (2018—) and the Settler Colonial City Project (2019—), both co-founded with Andrew Herscher, have been key in understanding these topics. The students of “Histories of Architecture Against” (Fall 2019) at the University of Michigan helped me think through these categories. A longer, earlier version of this text was originally presented in Mexico City at the CIHU congress in Fernando Luiz Lara and Reina Loredo’s panel “Rompiendo Fronteras Coloniales.” I am thankful to their call to think about these histories.

[2] See Eve Tuck (Aleut) and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1:1 (2012): 3.

[3] The Modernity/Coloniality group includes the work of Walter Mignolo, Aníbal Quijano, Ramón Grosfoguel, Arturo Escobar, Fernando Coronil, Javier Sanjinés, Enrique Dussel, and others. The project starts roughly in 1998 and includes both collective and individual books.

[4] Aimé Césaire, Discours sur le colonialisme (Paris: Éditions Reclame, 1950) and Frantz Fanon, Les damnés de la terre (France: Éditions Maspero, 1961). For more on the intersection between Black and Native studies see Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019).

[5] Anni Ankitha Pullagura in the introduction of her recent CAA panel with Anuradha Vikram, “A Third Museum is Possible: Towards a Decolonial Curatorial Practice.” Collegiate Art Association Annual Conference, 14 February 2020, Chicago, IL. In working through these ideas I’m also indebted to Ananda Cohen-Aponte’s beautiful response to “Working with Decolonial Theory in the Early Modern Period,” CAA 13 February 2020, Chicago IL.

[6] Tuck and Yang, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” 1. Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui has made an eloquent critique of the Modernity/Coloniality group from an Indigenous perspective. Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, “Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: A Reflection on the Practices and Discourses of Decolonization,” South Atlantic Quarterly (2011), 111(1): 95-109. For a conversation across these differences, see “Thinking and Engaging with the Decolonial: A Conversation Between Walter D. Mignolo and Wanda Nanibush,” in Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, no. 45 (Spring/Summer 2018): 24-29.

[7] This is not to say that Indigenous peoples have not been under attack in societies that do not strictly fit settler colonial frameworks.

[8] For an environmental history after settler occupation in New England, see William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983).

[9] Nick Estes, Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (London: Verso, 2019).

This piece was originally written for, and printed in, Harvard Design Magazine #48: “America ,” 2021

Welcoming 2022–2023 Pollman Fellow Emmanuel Kofi Gavu

The Harvard Graduate School of Design is pleased to welcome Emmanuel Kofi Gavu as the Pollman Fellow in Real Estate and Urban Development for the 2022–2023 academic year.

Gavu (Dr.-Ing.) is a senior lecturer at the Department of Land Economy, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, Ghana. He completed his PhD in Spatial Planning at the TU Dortmund University in Germany. He also holds an MS in GIS for Urban Planning from the University of Twente in the Netherlands and a BS in Land Economy from KNUST Ghana.

Gavu is primarily interested in applications of GIS in urban management, real estate, and housing market analysis. He has published in the areas of hedonic modeling, housing market dynamics, and real estate education. A short-term consultant for the World Bank, Gavu is also a board member of the African Real Estate Society (AfRES), serves as chair of the Future Leaders of the African Real Estate Society (FLAfRES), and is a member of the Ghana Institution of Surveyors (GhIS). At the GSD, Gavu plans to work on the pricing of residential rental housing units in the Global South during global shocks, including pandemics. His goal is to provide information to housing market stakeholders that will enable them to understand the operations of the rental market during global shocks and to offer policy directives based on findings.

One of the fellowships and prizes administered by the GSD’s Department of Urban Planning and Design, the Pollman Fellowship was established in 2002 through a gift from Harold A. Pollman. It is given yearly to an outstanding postdoctoral graduate in real estate, urban planning, and development who spends one year in residence at the GSD as a visiting scholar.

Excerpt from Harvard Design Magazine: “The Perpetual Stranger” by Elijah Anderson

What is driving the surge of incidents in which white people have called the police to report Black people who are simply going about their business—hanging out at Starbucks, birding in Central Park, or as was the case recently for a small group of middle-class Black women, talking too loudly on a train in California wine country.

Part of the answer has to do with the ubiquity of cell phones, which facilitate rapid reporting of racial incidents to police and the news media, along with social media, which bring news of the same incidents to the public with nearly equal speed. Yet there is also a sociological explanation.

White people typically avoid the Black space, but Black people are required to navigate the white space as a condition of their existence.

And many white people have not adjusted to the idea that Black people now appear more often in “white spaces”—especially in places of privilege, power, and prestige—or just in places where they were historically unwelcome. When Black people do appear in such places, and do not show what may be regarded as “proper” deference, some white people want them out. Subconsciously or explicitly, they want to assign or banish them to a place I have called the “iconic ghetto”—to the stereotypical space in which they think all Black people belong, a segregated space for second-class citizens.

A lag between the rapidity of Black progress and white acceptance of that progress is responsible for this impulse. It was exacerbated by the previous presidential administration, which emboldened white racists with its racially charged rhetoric and exclusionist immigration policies.

Over the past half-century, the United States has undergone a profound racial incorporation process that has resulted in the largest Black middle class in history—a population that no longer feels obligated to stay in historically “Black” spaces, or to defer to white people. When members of this Black middle class (and other darker-skinned Americans, too) appear in civil society today, and especially in “white” spaces, they often demand a regard that accords with their rights, obligations, and duties as full citizens of the United States of America.

Yet many white people fundamentally reject that Black people are owed such regard, and indeed often feel that their own rights and social statuses have somehow been abrogated by contemporary racial inclusion. They seek to push back on the recent progress in race relations, and may demand deference on the basis of white skin privilege.

As these whites observe Black people navigating the “white,” privileged spaces of our society, they experience a sense of loss or a certain amount of cognitive dissonance. They may feel an acute need to “correct” what is before their eyes, to square things, or to set the “erroneous” picture right—to reestablish cognitive consonance. White people need to put the Black interlopers in their place, literally and figuratively. Black people must have their behavior corrected, and they must be directed back to “their” neighborhoods and designated social spaces.

Not bold enough to try to accomplish this feat alone, many of these self-appointed color-line monitors seek help from wherever they can find it—from the police, for instance. The “interlopers” may simply want to visit their condo’s swimming pool, or to sit in Starbucks or meet friends there before ordering drinks, something white people typically do without a second thought, or take a nap in a student dorm common room, make a purchase in an upscale store, or jog through a “white” neighborhood.

For the offense of straying—for engaging in ordinary behavior in public and being Black at the same time—they incur the “white gaze” along with a call to the police. And we all know what can happen then. When the police have killed Black people—which seems epidemic—they have almost never been held accountable. The George Floyd case was an exception.

In times past, before the civil rights revolution, the color line was more clearly marked. Both white and Black people knew their “place,” and for the most part, observed it. When people crossed that line—Black people, anyway—they faced legal penalties or extrajudicial violence. In those times, to live while Black was to be American and nominally free but to reside firmly within a virtual color caste—essentially, to live behind the veil, as W.E.B. Du Bois put it in The Souls of Black Folk.

Continue reading on the Harvard Design Magazine website…

“The Perpetual Stranger” by Elijah Anderson is excerpted from Issue No. 49 of Harvard Design Magazine: Publics. It has been adapted by the author from his new book, Black in White Space: The Enduring Impact of Color in Everyday Life (University of Chicago Press, 2021).

Summer Reading 2022

Looking for something design-related to read this August? In this list of recent publications by GSD faculty, alumni, and students, you can find everything from a deep dive into cross-laminated timber to a murder mystery set during a design competition.

John Ronan (MArch ’91) recently published Out of the Ordinary (Actar Publishers, 2022), showcasing the firm of John Ronan Architects and its spatial-material approach to architecture.

Stanislas Chaillou (MArch ’19)’s Artificial Intelligence and Architecture: From Research to Practice (Birkhäuser, 2022) explores the history, application, and theory of AI’s relationship to architecture.

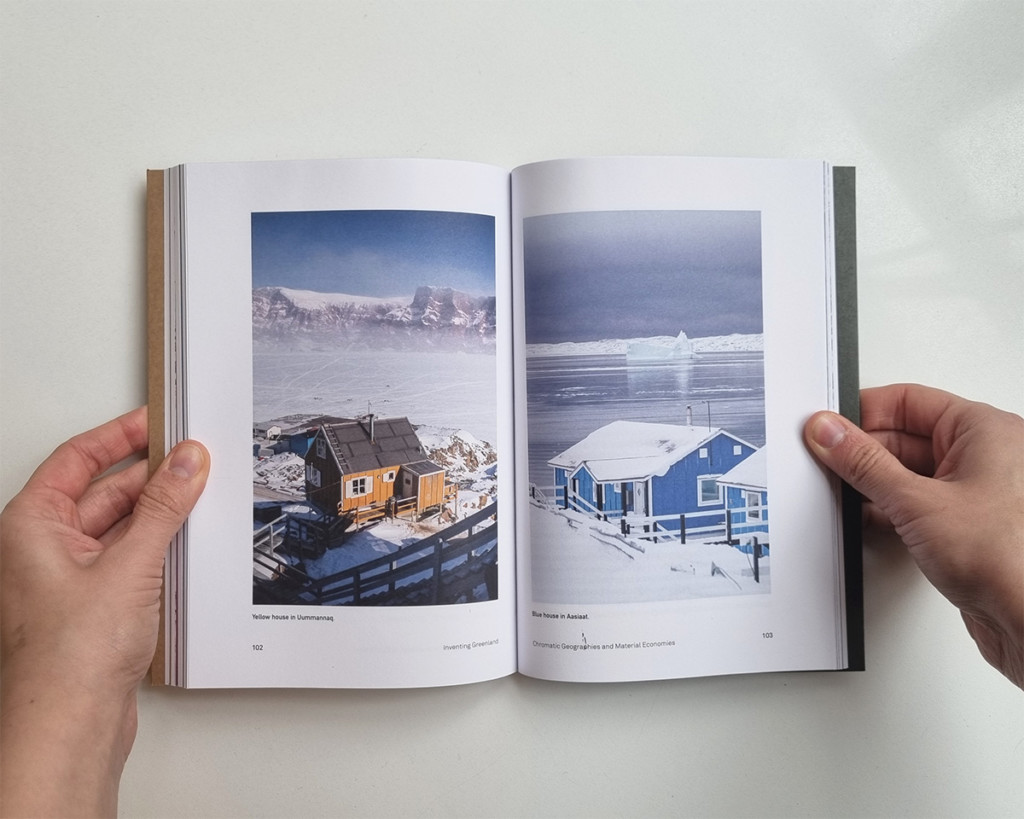

Bert De Jonghe (MDes ’21, DDes ’24) examines the intense transformation of Greenland through the lens of urbanization in Inventing Greenland: Designing an Arctic Nation (Actar, 2022). The book is based on De Jonghe’s MDes thesis, which was advised by Professor of Landscape Architecture Charles Waldheim.

Verify in Field (University of Chicago Press, 2022) is the second book from the firm Höweler + Yoon, founded by Eric Höweler (associate professor in architecture) and J. Meejin Yoon. It features recent designs by Höweler + Yoon, including the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia; a floating outdoor classroom in Philadelphia; the MIT Museum; and a pedestrian bridge in Shanghai’s Expo Park.

Blank: Speculations on CLT (Applied Research + Design Publishing, 2021), by faculty members Hanif Kara and Jennifer Bonner, explores the history and future of cross-laminated timber as a building material.

The Kinetic City & Other Essays (ArchiTangle, 2021) presents selected writings from Rahul Mehrotra, chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design and John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization. Mehrotra writes about the concept of the “Kinetic City” (as opposed to the “Static City” conceptualized on many city maps) and argues that the city should be seen as “patterns of occupation and associative values attributed to space.”

Looking for fiction? Check out Death by Design at Alcatraz (Goff Books, 2022) by Anthony Poon (MArch ’92). Described by LA Weekly as “The Fountainhead meets Squid Game,” it’s a mystery about architects being murdered during a competition to design a new museum at Alcatraz.

Photographer Mike Belleme and landscape-urbanist Chris Reed, professor in practice of landscape architecture at the GSD, collaborated on Mise-en-Scène: The Lives & Afterlives of Urban Landscapes (ORO Editions, 2021). It includes case studies of seven cities: Los Angeles, Galveston, St. Louis, Green Bay, Ann Arbor, Detroit, and Boston. Reed describes Mise-en-Scène as “a collection of artifacts and documents that are not necessarily intended to create logical narratives, more intended as a curated collection of stuff that might reverberate . . . to offer multiple readings, multiple musings, multiple futures on city-life.”

What makes an environment “responsive”? Responsive Environments: An Interdisciplinary Manifesto on Design, Technology and the Human Experience (Actar, 2021), from the GSD’s Responsive Environments and Artifacts Lab (REAL) and co-authored by Associate Professor in Practice of Architectural Technology Allen Sayegh, Stefano Andreani (MDes ’13), and Matteo Kalchschmidt, uses case studies to examine our “technologically-mediated relationship with space.”

Formulations: Architecture, Mathematics, Culture (MIT Press, 2022) by Andrew Witt, associate professor in practice, draws from Witt’s GSD seminar “Narratives of Design Science” and examines the relationship between mathematical calculation systems and architecture in the mid-20th century.