Excerpt from Harvard Design Magazine, “South Side Land Narratives: The Lost Histories and Hidden Joys of Black Chicago,” by Toni L. Griffin

Publicly expressing Black pain can render reactions of solidarity, healing, and empowerment, or exhaustion, guilt, and helplessness. However, Black voice can be a powerful instrument of change—used as a currency to be saved or spent or as a carrier of demand and solution. The past year has unearthed untold knowledge that gives additional context to the root of what drives this voice—its trauma, its demands, and its joy. Making this knowledge more public can help to inform how we understand and engage one another; how we reframe harmful Black narratives that shape the public perception; and how the power of Black creativity and resiliency as a political device can produce spaces of Black-centered freedom and liberation.

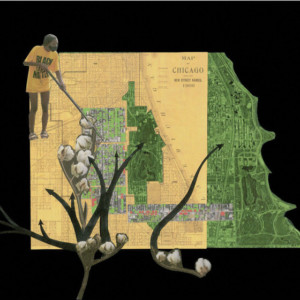

This essay and the corresponding collages aim to represent and make public the confrontation of pain and quest for joy found in the Black public realm of Chicago’s Mid-South Side. Each collage illustrates the relationship between publicness for Black Americans and the current urban landscape of vacancy including southern migration in response to public denial; the public scars left by urban renewal’s land mutilation; and the relentless pursuit of public freedoms in the public realm. The series offers a reflection on the contests that exist over land, space, and place alongside the aspiration of Black Americans to simply occupy and be carefree in public, unencumbered by fear and liberated from self-consciousness.

The collages include present-day mapping, photography, and historic images, in combination with clippings from, and references to, the imagery and symbols of Chicago’s Black life and prosperity used in the work of notable African American artists. My objective was to create new portrayals of the South Side and its people by making public some of the lesser-known narratives about these neighborhoods over the last century.

The narratives, rooted in the ownership and occupancy of land, reveal the practices of institutional racism, exclusion, and extraction, juxtaposed against images of the undiminished spirit, ambition, productivity, and creativity of Black Chicagoans. Richard Wright describes this as the “extremes of possibility” in his introduction to Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City, the seminal 1945 book by University of Chicago researchers St. Claire Drake and Horace A. Cayton on Negro life in Chicago: “There is an open and raw beauty about the city that seems either to kill or endow one with the spirit of life. I felt those extremes of possibility, death and hope, while I lived half hungry and afraid in a city to which I had fled with the dumb yearning to write, to tell my story.”[1]

BLACK MIGRATION | PUBLIC DENIAL

AVAILABLE WITHOUT FREEDOM | In the introduction to Black Metropolis, Richard Wright describes white Chicagoans questioning why Black migrants willingly uprooted themselves from the South, given the racial animosity and rapidly deteriorating built environment of Chicago’s South Side in the early 1900s. Between 1916 and 1970, six million African Americans migrated from the rural South to industrial cities in the Midwest and Northeast. In the first five years of the migration, Chicago saw a 50 percent increase in the Black population—from 46,000 to over 83,000 residents; by 1937, more than 237,100 Black Americans called the South Side home. [2]

Fleeing the Jim Crow South meant the possibility of industrial rather than agricultural work, with the promise of better wages and greater public freedoms to move about the city. Upon arrival however, migrant Blacks were confronted by a different form of public denial. Throughout the Jim Crow era, when separate but equal was the law of the South, northern cities maintained a different form of discriminatory practices perpetuated by white homeowners, real estate agents, lenders, and employers. Racial restrictive property covenants, redlining, and blockbusting formed an impenetrable barrier, intentionally constraining the geographic and economic mobility of Blacks in the city. These practices simultaneously and systematically devalued Black land assets and deepened the narratives of Black inferiority and Black neighborhood undesirability. The new Black Chicagoans found themselves spatially confined to an area that would become the Chicago Black Belt, unable to avail themselves of all the offerings of urban life.

Today, the Black Belt is simply referred to as the South Side. For a Black Chicagoan, growing up on the South Side is to be nourished in Black space, but often with little knowledge of the forced restriction that once bound people together in place. Nonetheless, the South Side now proudly belongs to Black Chicagoans, and their claim is validated by its history of confinement.

AN UNGUARANTEED EXISTENCE incorporates the three Great Migration routes used by Black Americans to access the greater personal freedoms and fortunes promised by cities outside of the southern states. The routes are intertwined with thorny cotton stalks representing the escape from chattel slavery and journey toward the Chicago Black Belt. Underneath is a 2020 aerial map of the Washington Park and Woodlawn neighborhoods, where over 200 acres of publicly owned vacant land appear as green voids on the map similar to the formal park spaces of the neighborhood. These vacant lands, the byproduct of urban renewal, disinvestment, and Black population exodus from the South Side, are demanding a new form of land care by remaining residents. Today, however, tending the land is not generating wealth for anyone; instead it is a temporary investment of sweat equity to cultivate greater safety, beauty, and mental well-being while residents wait for redevelopment.

Continue reading on the Harvard Design Magazine website…

“South Side Land Narratives: The Lost Histories and Hidden Joys of Black Chicago” by Toni L. Griffin is excerpted from Issue No. 49 of Harvard Design Magazine: Publics.

Mise-en-Scène: A new book from Chris Reed and Mike Belleme explores the theater of urban landscapes

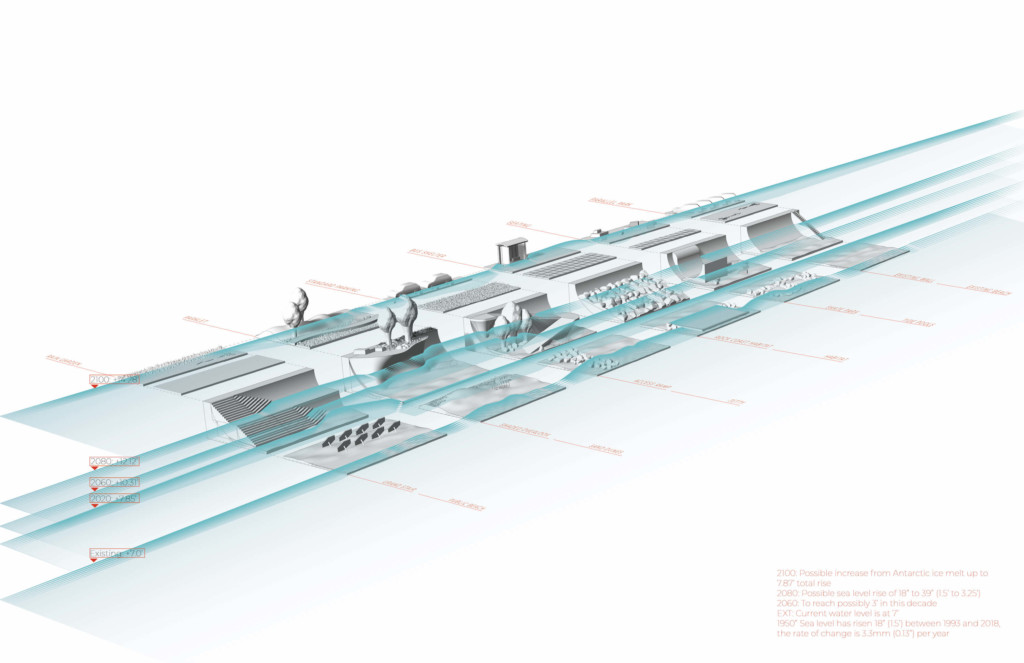

Conceived as a multidimensional investigation into “the social lives of urban landscapes,” Mise-en-Scène: The Lives & Afterlives of Urban Landscapes (ORO Editions) is a powerful collaboration between photographer Mike Belleme and landscape-urbanist Chris Reed, professor in practice of landscape architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. The book is centered around seven case studies: Los Angeles, Galveston, St. Louis, Green Bay, Ann Arbor, Detroit, and Boston. It intersperses photo essays by Belleme with selected maps, drawings, and wireframe renderings of projects from Reed-led landscape firm Stoss Landscape Urbanism , along with essays from guest contributors, quotes from contemporary and historical writings on the city, and interviews with residents. Reed describes Mise-en-Scène as “a bit of a scrapbook, a collection of artifacts and documents that are not necessarily intended to create logical narratives, more intended as a curated collection of stuff that might reverberate, one thing off another, to offer multiple readings, multiple musings, multiple futures on city-life.”

In the context of theater, “mise-en-scène” refers to the arrangement of scenery, props, and actors onstage, and in a broader sense, to environment or milieu. Reed draws out both of these connotations through the book, describing the work he does as “understanding the scripts and dialogues as they are playing themselves out; interacting with those on stage and the forces behind the scenes in ways that both respond to and shift what is at work; re-setting the trajectory of the play in ways that sometimes reveals what is hidden; and giving new voice to those who have been off stage—all allowing for new and healthier interactions among urban dwellers, their cities, and the environments in which they live.”

Through the triangulation of what is, what was, and what ought to be, photography and design prompt one to indulge in the kind of utopian imagination necessary to energizing activism.

The book features textural black-and-white photography, often shot at street level, and unwavering in its portrayal of gritty detail that highlight the many facets of a city. Candid images of people, landscapes, and built form are occasionally overlaid with sketches and annotations. Through his photography, Belleme captures small, everyday moments of joy or interest and finds commonalities across cities, despite differences in size, density, and environmental features.

The maps in the introduction of each of the cities make obvious the difference in scale, morphology, and geographical features of the cities, and yet an inherent interconnectedness emerges. Perhaps this can be explained by the quote from Teju Cole that the book opens with: “All the cities are one city. What is interesting to find, in this continuity of cities, the less obvious differences of texture: the signs, the markings, the assemblages, the things hiding in plain sight in each cityscape or landscape.”

And therefore, much as described by Jim Dwyer in Scenes Unseen: The Summer of ’78, or seen in William Whyte’s The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces (1980), which Reed lists as two of the influences for the book, there is a dynamic relationship of people’s interaction with public space, impacted by time of day, and patterns of sun and shade. The influence of The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces is clearly perceptible in the photographs—portraying people adapting the space to their own needs and using it as they see fit. As Reed says, “Many of Mike Belleme’s Mise-en-Scène photographs capture the rich social dynamics and urban-environmental conditions that we play off as designers and urban strategists; they document the lives of the places where we work, the afterlives of some of the places we have designed.”

The photo essays are interspersed with five essays from a diverse and interdisciplinary group of collaborators, to further provide framework. Curator Mimi Zeiger grapples with the issues of climatic and socioeconomic disparities in edge conditions in Los Angeles. Artist and activist De Nichols (LF ‘20) delves into issues of social equity and identity, along linear demarcations in cities such as St. Louis and Cleveland. Julia Czerniak analyzes the aesthetics and experiential quality of Stoss’s work, and speaks to the importance of aesthetics, in addition to today’s preoccupation with performance and sustainability. Nina-Marie Lister contextualizes landscapes within the climate crisis, and touches on issues of resilience and adaptation, stressing the need to work collaboratively across boundaries. In the final essay, Sara Zewde, assistant professor in practice of landscape architecture, reflects on the parallels of photography to design, positing them both as “acts of shaping how someone views the world.”

The writing is specialized, yet accessible, catering to activists, sociologists, aficionados of art, culture and photography, and city-lovers in general. These are spatial observations, and analyses of urban landscapes, but they are also deeply personal accounts. Nichols writes of her experience on the frontlines of protests in St. Louis that she was “harassed by patrons at the most deluxe mall of the county. I was tear-gassed in one the neighborhoods most lauded for its diversity and safety,” and Zeiger writes of the implicit privilege of inhabiting a white body in Pasadena.

Though the photographs were taken pre-pandemic, and this project has been four years in the making, the writings are oriented to a post-pandemic world. They reflect the inequity, systemic racism, and police brutality that were exacerbated by the pandemic, made glaring by the Black Lives Matter protests that swept the country. The photographs and writings shine a light on what the last two years have meant, environmentally and socially—and on the importance of having equitably accessible landscape spaces in our urban environments.

As Reed explains, “[Mise-en-Scène] is at once an artful documentary project on contemporary cities, city people, and the forces playing out across cities and public spaces everywhere. But it’s also a creative project about the future, about identifying pathways forward; about how people as individuals and entire communities, with artists, planners, designers, thinkers, government leaders, citizens, and activists can collaboratively shape our futures.”

And Zewde echoes, “Through the triangulation of what is, what was, and what ought to be, photography and design prompt one to indulge in the kind of utopian imagination necessary to energizing activism. There are striking similarities in the analytical endeavors of remembering the past, analyzing the present, and imagining a future. What worked? What didn’t? What is working? What isn’t working? What shall we conserve, destroy, and build in our new world? And, how do we advocate for it?”

If the pandemic and the past two years have taught us anything, it is that despite human resilience, and moments of celebration captured by Belleme, cities as they are today do not work. As design professionals, we have a chance to pause, recalibrate, and pivot toward a more equitable and climate-resilient future for our cities, and we must take it.

Toni L. Griffin Honored with Edmund N. Bacon Urban Design Award from Center for Architecture and Design

Toni L. Griffin, professor in practice of Urban Planning and Publics Domain head, is the 2022 recipient of the Edmund N. Bacon Urban Design Award . Given by Philadelphia’s Center for Architecture and Design , the award recognizes professionals who have made significant contributions to the field of urban planning through expert articulation of vision, communication, and improvement in their communities. Griffin joins an impressive legacy of Edmund N. Bacon Urban Design Award recipients, including Theaster Gates (LF ‘11), Denise Scott Brown, and Paul Goldberger.

Griffin was selected as this year’s recipient for her focus on design justice in the built environment. A central question in her work asks, “Would we design better places if we put the values of equality, inclusion, or equity first?” A press release from the Center also acknowledged Griffin’s alignment with “conversations the Center is having about the future of our student design competition and how we can use it to help students become better designers with an ubiquitous lens of equity, inclusion and justice in their approach to urban design, planning and architecture.”

Griffin’s firm, New York-based urbanAC , consults on planning and design revitalization projects with a focus on “historical and current disparities involving race, class, and generation.” Cities Griffin and urbanAC have had their hand in include Chicago, St. Louis, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, Memphis, and Detroit.

A graduate of the Loeb Fellowship Class of 1998, Griffin’s work to address, define, and stimulate the just city carry over to her engagements at the GSD. This semester, you can find her teaching “The Gentrification Debates: Perceptions and Realities of Neighborhood Change,” a seminar exploring the causes and effects of gentrification on national and city-specific scales. She is also the founder and director of the Just City Lab , a Harvard-based research center investigating the ways design can have a positive impact on addressing the conditions of injustice in cities.

Griffin will be honored in person and online and will give a talk at the Edmund N. Bacon Urban Design Award ceremony on March 24, 2022, in Philadelphia. Registration for the Zoom and in-person ceremony is required.

Stoss Landscape Urbanism Receives AIA Regional & Urban Design Award for Suffolk Downs Master Plan

Stoss Landscape Urbanism , the design studio founded by Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture Chris Reed, has received a 2022 AIA Award for Regional & Urban Design for the Suffolk Downs Master Plan. The annual AIA honors recognize “the best buildings and spaces—and the people behind them.”

Stoss received the award in partnership with Boston architecture firm CBT . The plan for the former horse racing facility in East Boston would create a highly resilient, mixed-use neighborhood oriented around transit. Studio director in the Boston office of Stoss and Design Critic in Landscape Architecture Amy Whitesides (MLA ’12) served as the director-in-charge for the project, with Reed acting as design director.

In addition to earning the AIA award, work by Stoss is featured as the cover story in the February 2022 publication of Landscape Architecture Magazine . The article reports on the design of a new central quad at the University of Michigan’s North Campus.

Reed also recently participated in an interview with the Canadian magazine Landscapes | Paysages , speaking with Snøhetta’s Michelle Delk and Dialog’s Doug Carlye about the future of landscape architecture. Asked to give advice for the new era, Reed says: “Embrace the challenges. Embrace the complexity. Don’t put it aside. And then find your own obsession, your own parallel obsession, and keep at that, too. Find your creative medium.”

Grace La and James Dallman Appointed First GSD Graduate Commons Program Faculty Directors

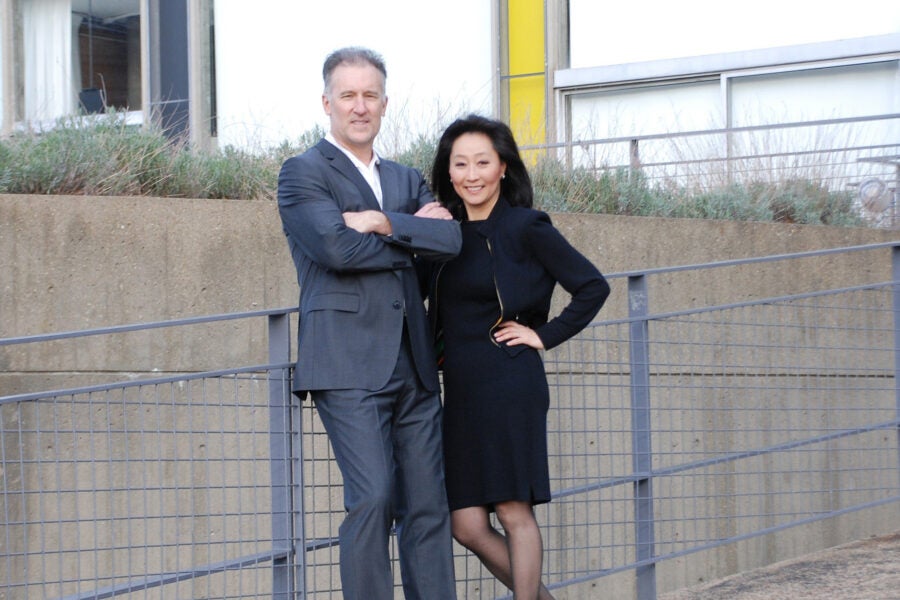

Grace La, professor of architecture and chair of the Practice Platform, and her husband, James Dallman (MArch ’92), have been appointed the newest faculty directors as part of Harvard’s Graduate Commons Program (GCP) . They are the first couple from the GSD to serve in the role, in which they will direct interdisciplinary, university-wide programs, serving as the intellectual leaders of the graduate residential communities of the GSD, HBS, FAS, and SEAS.

“We are thrilled to have our first GSD faculty directors joining us next year,” says GCP Director Lisa Valela . “In conversations with former HUH residents and interns, we learned that Grace and James share a commitment to mentoring and supporting graduate students.”

The couple will become the leaders of 10 Akron Street beginning in the fall of 2022. “James and I are delighted to join the distinctive GCP program, which enables us to contribute to the intellectual life at Harvard in new and expansive ways,” says La . “We look forward to collaboration across the university.” They will be joined by their two sons.

La and Dallman both hold degrees from the GSD. La graduated from Harvard College in 1992 and received her MArch from the GSD in 1995, and Dallman graduated with an MArch from the GSD in 1992. The pair are also principals and cofounders of the architecture practice LA DALLMAN .

This spring, La is leading the design research studio “Eco Folly” alongside Erika Naginski, Robert P. Hubbard Professor of Architectural History. The studio and corresponding seminar uses the folly opportunistically to create “a space of design experimentation in which participants will explore the behavior of materials, understand the life-cycle of buildings, and evaluate sustainable consequences.” The design work will be exhibited at the GSD’s House Zero this coming fall, and is generously funded by the Center for Green Buildings and Cities and the Department of Architecture.

Learn more about La and Dallman’s new leadership role in the Harvard Gazette .

Design Proposals for the Uncertain Future of American Infrastructure

As the world ground to a halt in the spring of 2020, with the COVID-19 pandemic shuttering shops, schools, subways, and offices, a street in Queens opened itself up as a new site of social infrastructure. [1] Located in Jackson Heights, one of the most congested neighborhoods in New York City with among the least green space per capita, a 26-block stretch of 34th Avenue was transformed into a 1.3-mile-long “vertical park” by the grassroots 34th Ave Open Streets Coalition. For 12 hours a day, every day, the street closed down to cars, permitting weary workers, solo-living seniors, and working-from-home parents and their children to stretch their legs, join in socially distanced exercise classes, swing by a community-led food pantry, or tend to a communal median garden that was—finally—their own.

Heralded as a visionary prototype for a more equitable and sustainable future city, the project also underscored the importance of civic space in an era marked by increasing privatization of the public realm. Reclaiming the street within a pandemic that both exposed and exacerbated the stark inequities of access to healthcare, community support, and green space across the United States framed the necessity of such spaces, in the words of sociologist Eric Klinenberg, as a matter of life or death. [2] In a keynote lecture recently delivered at the GSD , Klinenberg highlighted 34th Avenue as a success story within a larger domestic policy movement toward an expanded definition of infrastructure, in part fueled by the pandemic. “The pandemic forced us to hunker down and maintain physical distance,” says Klinenberg. “But we also developed newfound appreciation for gathering places that we had taken for granted. My hope is that we channel that into support for social infrastructure. We’re living through a unique moment, and we’re poised to make transformative investments in the physical systems that sustain us.”

Such an investment may begin through the Biden administration’s Build Back Better framework. Viewed as one of the most significant domestic policy agendas since the New Deal of the 1930s and the Great Society of the 1960s, Biden’s original $3 trillion BBB plan comprises two pieces of legislation: the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill, signed into law on November 15, and the $1.75 trillion Build Back Better (BBB) bill, which remains stalled after a firm rebuke from Senator Joe Manchin.

The infrastructure bill (also called the public works law) addresses what we typically think of as infrastructure, and offers the largest investment in the sector in over a decade. It includes funding for repairing and expanding roads, bridges, mass transit, and rail service, as well as upgrades to ports, electric grids, and water infrastructure. It casts a wide net across the country, including the replacement of lead pipes in Illinois, bridge repairs in Massachusetts, regional transit connections in Louisiana, and abandoned mine cleanup in Kentucky. In addition to bolstering material infrastructure, the bill hones in on the so-called “digital divide,” funneling $65 billion into expanding broadband access to rural and disadvantaged communities in the US.

The controversial BBB bill—focusing on what it terms “human infrastructure,” or social infrastructure—includes allocations of $150 billion for new affordable housing, $550 billion for climate-related policy and programs, $18 billion for universal pre-K, and $200 billion for childcare. For political reasons, however, many of these provisions will be absent from the bill, if it ever clears the senate. Both bills are the first pieces of federal legislation in over a decade to address the climate crisis and suggest solutions for mitigating the impact of global heating.

Across both bills, the idea of infrastructure expands to include social reform, digital telecommunications networks, climate justice, clean energy, and affordable housing. In addition to Klinenberg’s keynote, multiple studios and seminars at the GSD last term attempted to grapple with this multifaceted understanding of infrastructure. “That the Biden bill recognizes and supports social infrastructure, the economies of care, and reproductive labor, particularly at the household scale, is an exciting step for a country wherein everything has been relentlessly privatized,” says Malkit Shoshan, who taught “Reimagining Social Infrastructure and Collective Futures” in the fall. “By strengthening the household economy, stronger households can better interact with other households and create a commons. These issues should be essential to talking about the future of infrastructure—that it’s a matter of the values we preserve as a society.”

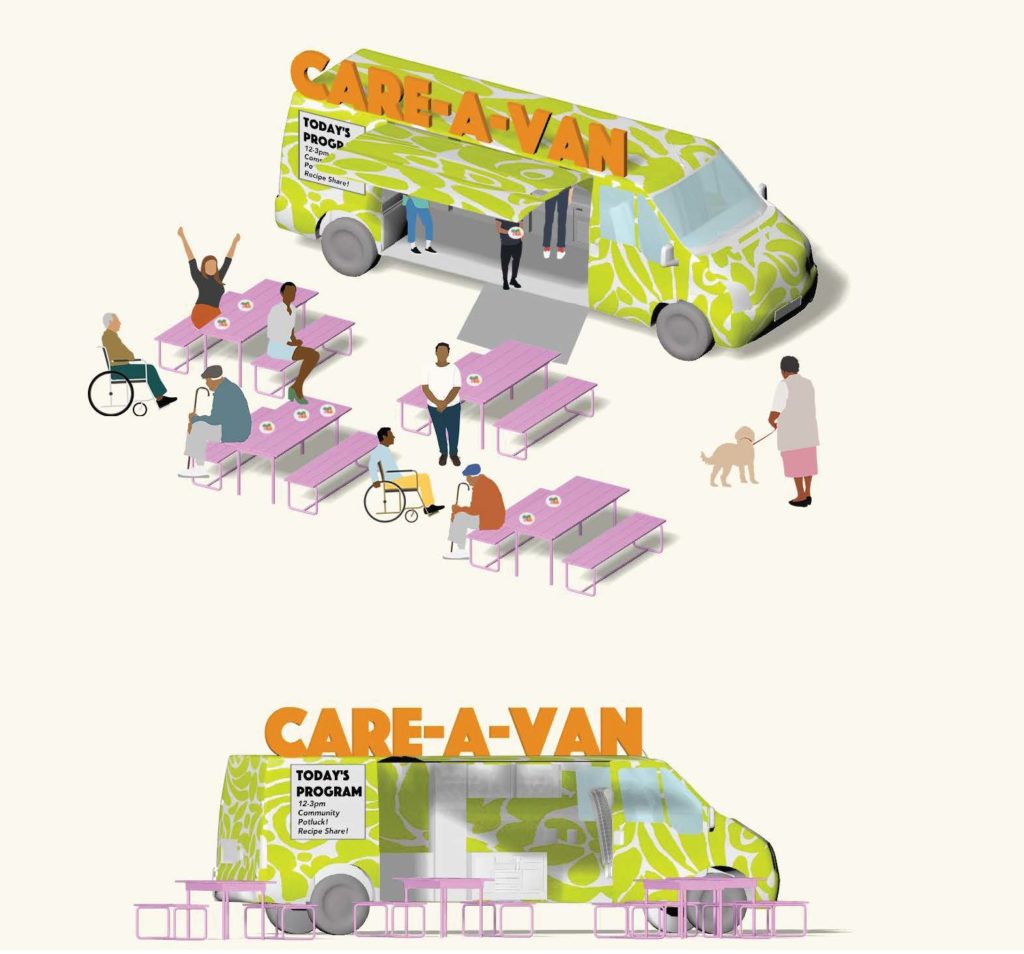

Shoshan framed her project-based seminar with key theories intersecting the social sciences, economics, feminist theory, and ecology, including those of economist Kate Raworth, author of Doughnut Economics, and philosopher Sylvia Federici, whose writings on reproductive labor have found new relevance during the pandemic. Students were asked to envision a more intersectional social infrastructure, where the well-being of mothers, caregivers, the elderly, and other marginalized groups, as well as precarious public services, were integrated into a collective future vision of a healthier planet. Among the projects to emerge from the seminar was a reimagining of the post office infrastructure, which is at risk of privatization, as well as a mobile “Care-a-Van” that revitalizes the lives of the elderly and reintegrates them into public spaces, generating new social networks. A “school for the future” sought to support an underserved public high school in East Boston, the largest in the area, in a neighborhood expected to be flattened by sea-level rise as early as 2050. In addition to providing climate infrastructure, the project proposed opening up the physical infrastructure to community use in after-school hours.

Ron Witte’s studio, “ROOM,” took a micro-scale lens to the question of what constitutes good social infrastructure, from the design perspective of the public interior. Utilizing a new reading room for the Central Boston Public Library as a case study, students were asked to envision alternative design protocols for indoor institutional spaces in an era where the role of such spaces is expanding as social infrastructure. Proposals varied widely, from reimagining the cultural status of the library to a “high-tech medium,” where visitors are given a window into the guts of archival space through a series of tubes transporting reading materials, to cracking the institution open like an egg, making its processes visible from the outside and expanding the internal boundaries of the building. “Architecture has been pushed to the side in this conversation around the future of infrastructure,” says Witte. “We’ve tended to focus on broad questions around social infrastructure, economies, and public spaces, but without architecture to prompt them into a new state, nothing will happen.”

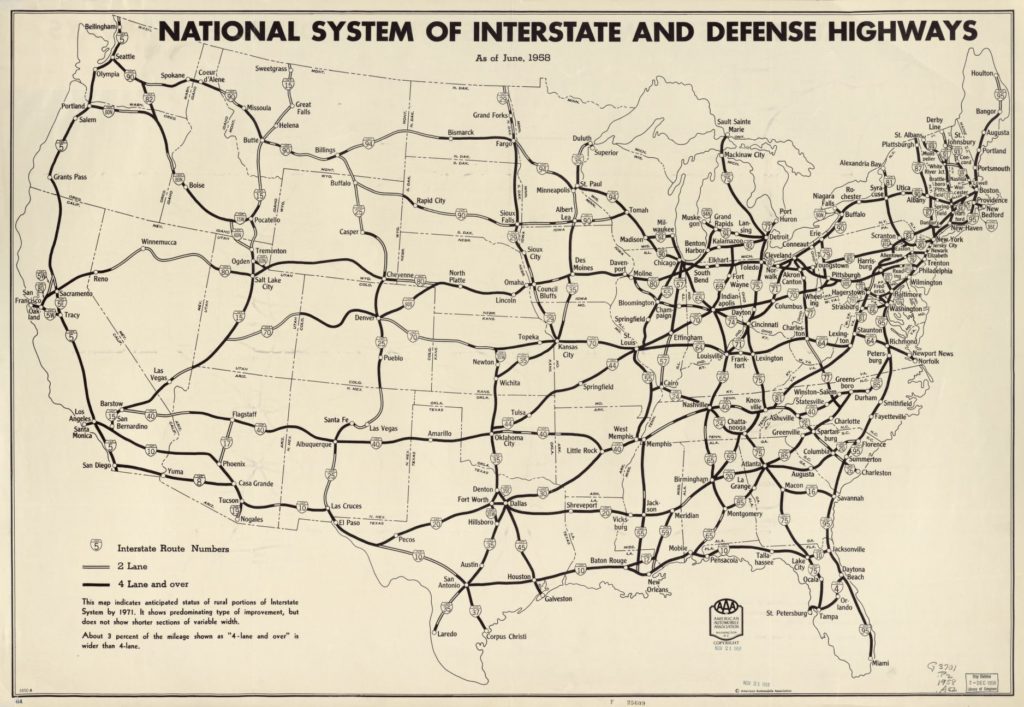

Additional federal efforts are necessary to ensure the Building Back Better framework’s climate resilience funds meet those who need it most. The new White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council is a step in the right direction, with 26 leaders from diverse communities appointed to judge applications for community-led climate infrastructure projects. [3] But there must also be increased support at the local level, to ensure these communities have no barriers to accessing funds and can realize these projects collaboratively. Responding to this condition, Dan D’Oca’s fall studio, “Highways Revisited,” was an exercise in reimagining the future of 10 cities and their surrounding highway systems. Each student was connected with a local activist or government official to envision an alternative use for that highway infrastructure while taking stock of its historical damage to disadvantaged communities.

Whittled down from a short list of 50 areas, the selected sites cover a wide range of topologies and racial and socioeconomic spectrums—they include El Paso, the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston, Detroit, Oakland, and New Orleans. “The idea was to find examples of cities where there was already a conversation about highway removal, but where things weren’t so settled,” explains D’Oca. “It was important for students to be able to think big and dream, but also have the guidance of a good liaison, and the tenability of a pitch process.”

“When you destroy a neighborhood you don’t just destroy homes, you destroy vehicles for amassing generational wealth.” – Dan D’Oca

With guidance from a lifelong resident of the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans (one of the oldest Black neighborhoods in the US, and the birthplace of jazz), one student transformed a stretch of I-10 that decimated the neighborhood into a powerful piece of community infrastructure, complete with public housing, green space, events programming, and an arts and music venue. (The White House has proposed removing the expressway altogether). For El Paso, another student nixed the freeway running along the US-Mexico border, restoring the original landscape of a green river valley and building a new neighborhood alongside it. In the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, a student worked with local liaisons to envision the removal of an eight-mile stretch of I-94, replacing it with a parkway, a rapid transit system, and new neighborhoods. The studio explored the emerging concept of “right to return,” currently piloted by the city of Santa Monica , which specifies Black communities displaced by mid-century urban renewal policies should be at the front of the line in new affordable housing markets. “When you destroy a neighborhood you don’t just destroy homes, you destroy vehicles for amassing generational wealth,” explains D’Oca. “So this idea of a ‘right of return’ being implemented by some local policymakers integrates the idea of infrastructure as an opportunity for reparations.”

Tom Oslund and Catherine Murray’s studio, “Harnessing the Future,” looked beyond the US to address the social, ecological, and economic entanglements of digital infrastructure in the small west Irish town of Asketon and the surrounding Shannon Estuary, where a new data center is slated for development. With a local environmental engineer as steward, students were tasked with reimagining the design of the data center to support the local economies and histories of Ireland, while adhering to the region’s strict conservationist protocols, and achieving carbon neutrality. One of the proposals utilized the energy of cow waste and Atlantic wind turbine production to fuel the data center. Another restricted its size and energy consumption to the amount of energy needed to churn Ireland’s signature domestic export, Kerrygold butter (and recycling the energy to do so). And the third proposal divvied up the area into wind energy–producing parcels of land owned by locals to sell back to data providers, flipping the power hierarchy between opportunistic data companies and residents. Oslund cites the main challenge with equivalent projects in the US as “a problem of too much land and too little restraint”—but is optimistic that an industry-led initiative for ecological design alternatives could catch on across the Atlantic. “The paradigm change that must happen is the responsibility of these companies,” he says. “Data centers have already surpassed airlines in carbon emissions, and there’s too much at stake. This studio was put in place to showcase more environmentally conscious design alternatives that support local economies and culture.”

As the future of the BBB remains uncertain, and the real work of the Infrastructure Bill lies ahead, it’s crucial that in expanding our definition of infrastructure, we take care not to divide it. A truly democratic approach to infrastructure acknowledges its constituency and responsibility across all sectors and publics: in other words, digital infrastructure must be social infrastructure; climate resilience infrastructure must also impart a civic value. Closing out his keynote lecture, Klinenberg gave a simple example for how this might be achieved: by revamping the design of a levee, which will be an increasingly common piece of infrastructure amid rising sea levels, to include a public park on top. What’s required is a crucial shift of perspective that enables new infrastructure. As Oslund says, it needs to “provide the same function, but allow for a different story.” There must be a design sensitivity on both a micro and macro scale to ensure it benefits those it has a particular duty to serve. The future of infrastructure requires a feminist design approach that centers marginalized groups; an equitable approach that incorporates reparations to communities who bore the damage wrought by earlier infrastructure projects; an ecological approach that acknowledges the stakes of the climate emergency; and the support of a public resource system that ensures the longevity of grassroots initiatives. Despite its warranted criticisms, the BBB framework offers a vital first step in this direction. Now, it’s up to designers and policymakers to get to work.

[1] In his book, Palaces for the People, sociologist Eric Klinenberg defines social infrastructure as a loose category of public places—parks, playgrounds, libraries, and town halls, as well as grocery stores, cafés, and barber shops—that are the spatial glue of a healthy society. Formal and informal, organized and happenstance, these are the hang-out spots where communities are made and people learn to look out for each other, particularly in times of crisis.

[2] Klinenberg’s acclaimed research on the “high resilience” areas of the 1995 Chicago heatwave pinpoints the significance of robust social infrastructure in contributing to low death tolls in otherwise demographically similar neighborhoods.

[3] Both bills intend to jumpstart the Justice40 Initiative ordered by Biden just days after taking office. It outlines that 40 percent of federal climate spending must reach underserved areas (formally defined as low income, rural, and/or communities of color), as a climate justice initiative. Despite these promises, critics argue this money will largely benefit middle-class, white communities .

New Book by Andrew Witt Examines the Visual Intersections of Architecture, Mathematics, and Culture

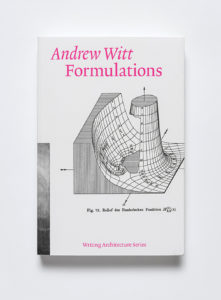

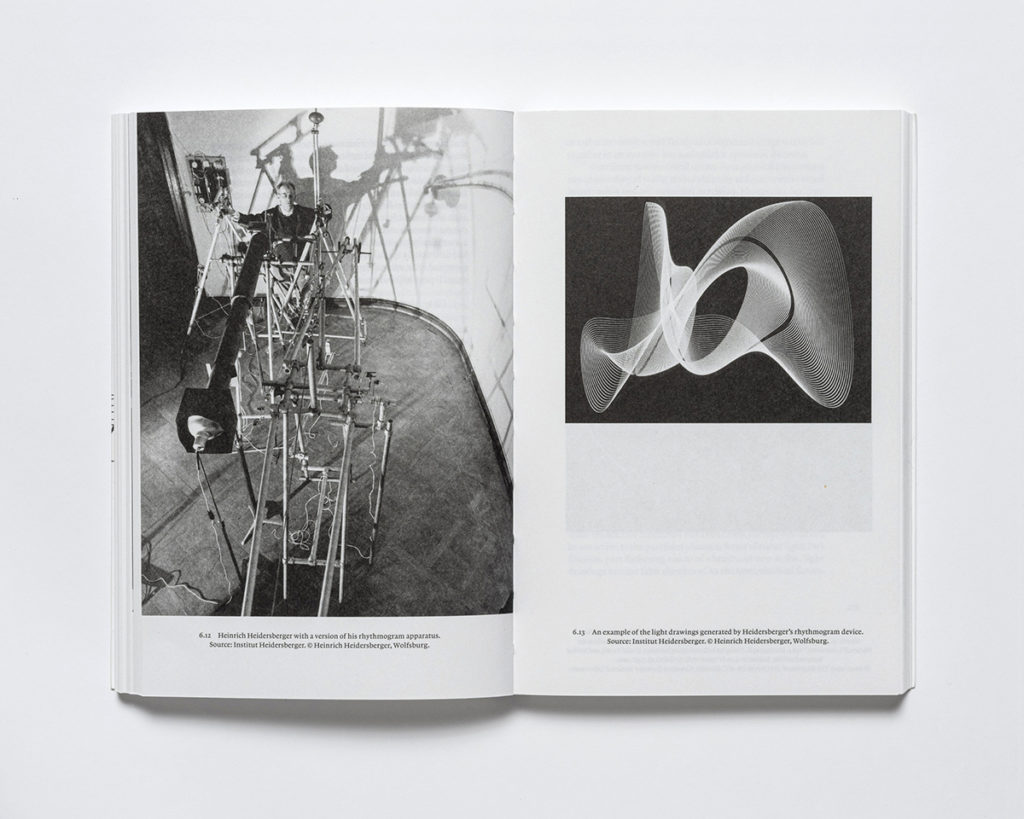

A new book by Associate Professor in Practice of Architecture Andrew Witt examines more than 150 years of seeing, drawing, and modeling architecture mathematically. It presents a rich tour of the drawing machines, geometric patterns, crystal structures, and stereoscopic images that connected modern architecture to modern science and expanded spatial imagination. The book’s research builds on the GSD seminar “Narratives of Design Science” led by Witt in past years.

Released in January 2022 by the MIT Press, Formulations: Architecture, Mathematics, Culture bridges the art of science and design. The book studies architecture’s encounter with mathematical calculation systems that were ingeniously retooled by architects for design. To illustrate initial exchanges between design and science, Witt provides a catalog of pre-digitization drawings and calculations from mid-twentieth-century mathematical practices in design. Formulations also takes up the “formal compendia that became a cultural currency shared between modern mathematicians and modern architects.”

As a way of illustrating the many ways mathematics penetrated design thinking as we know it today, Formulations examines a variety of innovations, including early drawing machines that mechanized curvature, the virtualization of buildings and landscapes through surveyed triangulation and photogrammetry, and stereoscopic drawing.

Antoine Picon, director of doctoral programs and G. Ware Travelstead Professor of the History of Architecture and Technology at the GSD, describes the book as a “brilliant and thought-provoking navigation through complex mathematical notions, models and machines, spatial patterns, and construction techniques. A must-read for anyone interested in the relationships between architecture, mathematics, and digital techniques.”

Formulations is part of the Writing Architecture series, edited by Cynthia Davidson, which includes previous contributions from Harvard faculty members including Giuliana Bruno, Edward Eigen, and K. Michael Hays. It is the first book in a complete graphic redesign of the series, by graphic designer Ben Fehrman-Lee .

Trained as both an architect and a mathematician, and a graduate of the GSD’s MArch and MDes programs, Witt’s research explores the relationship between architecture, science, and visual techniques through the lens of mathematics. He is also editor of the trilogy “Studies in the Design Laboratory ,” jointly published by the GSD and the Canadian Centre for Architecture. The final installment of the series, Tange Lab: The Quantified Economy and Urban Futurism, will be available online soon.

Learn more about Witt’s Formulations from the MIT Press .

Announcing the 2022 MICD Just City Mayoral Fellowship

The Just City Lab at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the Mayors’ Institute on City Design (MICD) are pleased to announce the launch of the 2022 MICD Just City Mayoral Fellowship, taking place in Spring 2022.

The 2022 MICD Just City Mayoral Fellowship will help mayors navigate a just and equitable recovery from the pandemic, providing actionable ideas for city leaders rising to meet this moment of change. Building on the inaugural 2020 Fellowship , this program will explore ways to create lasting, transformational impacts from new federal funding streams such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the American Rescue Plan Act. The Lab’s Just City Index will frame dynamic presentations and dialogues with experts in the fields of architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning, art activism, housing, and public policy. Over the semester-long program, mayors will identify how racial injustices manifest in the social, economic, and physical infrastructures of their cities and develop manifestos of action for their communities.

The 2022 MICD Just City Mayoral Fellows include Charleston, SC Mayor John J. Tecklenburg ; College Park, MD Mayor Patrick L. Wojahn ; Duluth, MN Mayor Emily Larson ; Madison, WI Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway ; Providence, RI Mayor Jorge O. Elorza; Richmond, VA Mayor Levar M. Stoney; Salisbury, MD Mayor Jacob R. Day ; and Youngstown, OH Mayor Jamael Tito Brown .

The Just City Lab is a design lab located within the GSD and led by architect and urban planner Toni L. Griffin. The Lab has developed nearly 10 years of publications, case studies, convening tools and exhibitions that examine how design and planning can have a positive impact of addressing the long-standing conditions of social and spatial injustice in cities. The Mayors’ Institute on City Design (MICD), the nation’s preeminent forum for mayors to address city design and development issues, is a leadership initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with the United States Conference of Mayors . Since 1986, MICD has helped transform communities through design by preparing mayors to be the chief urban designers of their cities.

“I’m delighted to see this powerful collaboration between the Just City Lab and the Mayors’ Institute on City Design continue,” says Sarah Whiting, dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture. “This year’s cohort of mayors come from many cities that are particularly interesting to our students as they consider their future plans. These are mostly middle-sized cities that are transforming quickly as a response to the skyrocketing costs of our nation’s largest urban centers. The Mayoral Fellowship is well-timed to help these eight mayors lead in terms of equity and opportunity. Our aspiration is that ‘just cities’ will become the standard for what we expect in this country, not the exception to what so many experience today.”

“Mayors have led our communities through a series of unrelenting challenges over the past two years. With new federal funding streams, we have a unique opportunity for once-in-a-generation change,” said Tom Cochran , CEO and executive director of the United States Conference of Mayors. “Mayors are now tasked with uniting their communities around real solutions and making transformational investments. The traditional MICD experience, with its candid, small-group format and access to national design experts, is so often transformative for mayors. There is no better model for empowering mayors to find solutions in our nation’s cities, and the United States Conference of Mayors is proud to partner with the Just City Lab to help guide mayors through this important chapter of American history.”

“Building on the National Endowment for the Arts’ vision to heal, unite, and lift up communities with compassion and creativity, we are proud and humbled to continue this important collaboration between MICD and the Just City Lab,” said Jennifer Hughes, NEA director of design and creative placemaking. “This program will take the transformative power of MICD, which illuminates the power of design to tackle complex problems, and apply it to the defining challenge of our time: ensuring equity and justice for everyone.”

On April 22, the 2022 Fellows will come together to discuss strategies for using planning and design interventions to address racial injustice in each of their cities at a GSD event hosted by Griffin. The program will be free and open to the public.

The Just City Lab and MICD are thrilled to continue this fellowship to help mayors shape more just cities. Learn more about the host organizations at www.micd.org and www.designforthejustcity.org .

Parts of this press release also appeared on the MICD website .

Jordan Weber, Germane Barnes, Design Earth Named 2022 United States Artists Fellows

Fellows and graduates of the Harvard Graduate School of Design are among the 63 recipients of 2022 USA Fellowships from national arts funding organization United States Artists (USA). Now in its 17th year, USA Fellowships provide recipients with an unrestricted $50,000 award to support their creative and professional development.

According to the United States Artists’ announcement , “The 2022 USA Fellows were selected for their remarkable artistic vision and their commitment to community—both within their specific regions and discipline at large.” They represent 23 states and Puerto Rico and span 10 artistic disciplines, including Architecture & Design.

Regenerative land sculptor and environmental activist Jordan Weber was honored with a fellowship in the Visual Arts category. He is the inaugural joint Loeb/ArtLab artist in residence , a collaborative program intended to enrich the Loeb Fellowship experience with studio space in the ArtLab and access to resources from the ArtLab community. This fall, “Perennial Philosophies ,” a public artwork by Weber commissioned by the Harvard University Committee on the Arts (HUCA), was unveiled on the grounds of the ArtLab. The sculpture responds to the dual pandemics of 2020—COVID-19 and racial injustice—and features an excerpt from “The Hill We Climb,” the poem written by Harvard graduate Amanda Gorman for President Biden’s inauguration.

Architecture & Design fellowship winner Germane Barnes leads Miami-based research and design practice Studio Barnes . His 2021 Wheelwright Prize–winning project, Anatomical Transformations in Classical Architecture, examines Roman and Italian architecture through the lens of non-white constructors. Barnes is also the recipient of a 2021-2022 Rome Prize in Architecture and a 2021 Architectural League Prize.

Cambridge-based research practice Design Earth was founded in 2010 by Rania Ghosn and El Hadi Jazairy (both DDes ’10) and honored with a USA Fellowship in the Architecture & Design category. The pair are founding editors of the GSD journal New Geographies and edited the “Landscapes of Energy” and “Scales of the Earth” issues. Ghosn and Jazairy are also associate professors of architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Michigan respectively.

The practice of 2020 Design Critic in Architecture Jennifer Newsom, Dream The Combine, which Newsom founded with Tom Carruthers, was also recognized with a USA Fellowship in the Architecture & Design category. Newsom led the fall 2020 option studio “Movements” at the GSD. Read an interview with Newsom on foregrounding the kinetic body in architectural representation.

In 2021, GSD professor Jennifer Bonner (MArch ’09) and Spring 2021 Senior Loeb Scholar Walter Hood received USA Fellowships. Other past recipients include 2019 GSD Class Day speaker Teju Cole (2015) and Johnston Marklee, the practice of GSD professors Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee (2016).

Mohsen Mostafavi Remembers Richard Rogers (1933-2021)

Richard Rogers was one of the few remaining major figures in architecture whose career and education had a direct link with the ideological project of the modern movement and its call for social change. Richard loved bright colors, in architecture and in clothing, and believed in the contribution of cities toward a better quality of life. More specifically, he championed urban regeneration on brownfield or disused sites with an emphasis on compactness and density.

Born in Italy and raised in the UK, his ideas and works were shaped by his European heritage. He was related to the celebrated Italian architect Ernesto Nathan Rogers, editor of Casabella magazine and a founding member of BBPR, the practice responsible for the iconic Torre Velasca in Milan.

Despite having dyslexia, Richard completed his diploma at the Architectural Association in London, where he worked with Peter Smithson, among others. He then continued his education at Yale under Paul Rudolph. His time at Yale coincided with that of another British architect, Norman Foster.

Richard will probably be best remembered for two of his practice’s most iconic buildings, the Pompidou Center in Paris (1977) and Lloyd’s in London (1986). The former was designed in collaboration with Renzo Piano; Peter Rice was the engineer on both.

However, it is two relatively small houses that helped define his characteristic approach toward architecture. The first of these, Creek Vean, was designed within the context of a collaborative practice, Team 4, made up of Richard Rogers, Norman Foster, and their then partners, Su Rogers and Wendy Ann Foster. Anthony Hunt was the engineer for the project, which was completed in 1966.

Looking at the house today, one wouldn’t associate it with the later work of either Richard Rogers or Norman Foster—apart, perhaps, from the open-plan interiors with their beautiful views of the landscape captured through the plate glass windows. Still, the house is important for Richard’s subsequent and lifelong commitment to teamwork and the idea of collaborative practice.

While Creek Vean was designed for Su’s parents, Richard soon had the opportunity to design a house in the London suburb of Wimbledon for his own parents, a doctor and a ceramicist. Based on an unrealized project, the Zip-Up house, it required the use of factory-made insulation panels that could be easily assembled on site. Ironically, given this dream of industrial production, the result was, to a large extent, a bespoke and handcrafted artifact. But the innovative and experimental house not only captures the DNA of Richard’s later work, it also exemplifies the sense of lightness, joy, and color that defines the best characteristics of his architecture.

On a personal note, I was fortunate to have Su Rogers amongst a group of teachers when I first started my architectural education. Later, during my tenure as the dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Richard and his second wife, Ruthie, generously gifted the Wimbledon house to the GSD. The house was meticulously restored by Gumuchdjian Architects. Philip Gumuchdjian had been a former student and had also worked with Richard for a long time before setting up his own practice. The landscape architect for the restoration of the garden was a GSD graduate, Todd Longstaffe-Gowan.

When the house was first built it had a carport, which was subsequently turned into a separate smaller house, creating an intimate courtyard with the main house. The two buildings, with the help of a generous donor, provided the basis for a GSD/Richard Rogers residential fellowship program. The aim of the Richard Rogers Fellowship was to enable designers and scholars from around the world to spend up to three months in London and to engage in the study of the built environment. Richard’s own interests in architecture, culture, technology, the arts, and the city provided the framework for the broader scope of the fellowship.

In addition, a series of events on the city, and London more specifically, brought a diverse range of speakers and experts together. Organized as a “salon,” these small gatherings of around 50 people in the main living room of the house created great opportunities for debate, on such topics as engineering and housing. It was inspiring to have Richard participate in these events and to meet and mentor the fellows. He also enjoyed the experience very much.

Richard and Ruthie spent about a week at the GSD a few years ago when we invited them to be the Senior Loeb Fellows. Ruthie, a celebrated chef, gave a wonderful talk about how they managed and organized the produce and the menu at her restaurant, the River Café. Richard met with students and talked about architecture and, as you might expect, about what it could do for society.

Probably more than any other architect of the recent past, Richard was committed to architecture and technology’s social and political impact. It can be argued that his practice’s work, especially the exclusive residential projects, didn’t always align with his intellectual and political beliefs. But during certain moments, the practice’s outcome genuinely challenged the relationship between architecture, technology, and the conditions of production. He also managed to be hugely influential for a period of time with Britain’s then ruling Labour Party by making architecture and the built environment topics of political significance that affect people’s quality of life, and indispensable cornerstones of democracy.

I will miss Richard’s friendship, warmth, and generosity. And of course, his flair for colors.