Can you depict a sweating body in an architectural drawing? Are lines capable of expressing the exhaustion felt when climbing a steep incline? And what is drawing’s capacity to represent the effects of powerlessness, fear, and objectification experienced by bodies that feel a space does not belong to them, as, for example, Black bodies too often do in America?

In her fall studio, “Movements,” Jennifer Newsom, design critic in architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, asks students to consider such questions which foreground the body—the kinetic body in particular—in architectural representation in order to illuminate problematic assumptions that dominate the discipline’s methods. “Much of my practice focuses on operating in public space and concentrating on the direct and visceral qualities of those experiences,” she says. “In some ways, those concerns can get neutered or left out when we think about architectural representation, which becomes very abstract. It’s important to be rooted and embedded in our own bodies, to acknowledge that we’re not some kind of god behind a curtain constructing spaces for people that we don’t also live in. We’re of the world, and for architects to act like we’re not is a falsehood.”

Who we center as our subject is a really important question when we talk about architecture. Who is it for? Who gets to make it? Whose world view does it help prop up?

Architectural renderings, and the future constructions for which they serve as a translation, are not inert but prescriptive in that they present permissible orientations for bodies within spaces. In other words, they dictate where bodies can move and how, what they can see and from what points of view, and whether, in turn, those bodies can be seen. Unlike most theatrical scripts, however, in these designs the role of the subject has often been pre-cast long before drawing begins, usually as an idealized white, heteronormative, able, cis-male body. Positioning this subject as central to a design or even as the only possible subject at best effaces those not considered proper subjects or recognizable bodies and at worst facilitates harm, both physical and psychical, against them.

A Cartesian approach would suggest that an inherent and universal truth exists behind the symbols used in such renderings, but phenomenology illuminates the tensions these seemingly benign orientations may contain and subsequently manifest in the built world. “Phenomenology asks us to be aware of the ‘what’ that is ‘around’ [the body],” writes Sara Ahmed, a British scholar working at the intersection of feminist theory, lesbian feminism, queer theory, critical race theory and postcolonialism. Everyone does not engage the ‘what’ identically, though. Ahmed references the feeling of “comfort” as an example of such differences. “To be comfortable is to be so at ease with one’s environment that it is hard to distinguish where one’s body ends and the world begins. One fits, and, by fitting, the surfaces of bodies disappear from view,” she observes fA . For most white bodies in the United States this feeling is de rigueur and accepted as a natural state of being. Whether walking by a police station, entering a concert hall, or running across the street at night, a white body can, more often than not, move through space seamlessly, even invisibly, as it and the space around it mutually influence and interact with each other. Its movements can seem unlimited, and it does not pay attention to being seen or of its ability not to be witnessed.

A Black body—especially a Black body adorned by symbols or moving in such a way marked suspicious by white bodies—is not an actor with power and privilege in the same spaces, however, but an object by which white bodies orient themselves. According to the French-Martinican psychiatrist and philosopher Frantz Fanon, the familiarity with one’s world determines a body’s ability to do and find things. A world that does not engage in a mutually constitutive relationship with its subject, a world in which that body lacks agency, transforms that subject into an object by which others orient themselves. That body becomes an object acted upon rather than a subject with agency, a body lost and unable to find its footing.

It is in this way, Ahmed argues, that whiteness exists: not as a race codified by perverse scientific fantasies, but as a kind of amniotic fluid through which white bodies and those that assimilate to their codes flow freely. It homogenizes them but also “makes non-white bodies feel uncomfortable, exposed, visible, different, when they take up this space.” Thus a Black or brown body (or a woman) could never assume the role of Baudelaire’s flaneur—the stroller who observes modern society from a detached position. “Who we center as our subject is a really important question when we talk about architecture,” Newsom says. “Who is it for? Who gets to make it? Whose world view does it help prop up?”

One of Newsom’s goals in the studio was to make students acknowledge up front that subjectivity and the experiences it does and does not enable affects the work they do. In order to facilitate that awareness and how it manifests in design, she asked students to perform walks in their environments, which were varied because of distance learning. “I gave them a list of prepositions such as on, between, against—words that are a kind of bridge in language and that have a spatiotemporal aspect,” she explains. “They picked five words and used them as intentions to guide their movements. They then made drawings representative of these qualities.” The objective was to make students aware of their own privilege or lack thereof, especially in public space, and of which spaces were and were not available to them. “It’s been interesting to hear them reflect on what’s afforded to them by their different environments and to use that experience as a provocation to think about race, the ableness of the body, gender, and the intention of a body in any particular space. You don’t build empathy outward if you don’t have a self-reflective capacity.”

Consider, as an example, the preposition out of in relation to the Jefferson grid. Embodying Enlightenment ideals of imposing order on what was deemed an untamed landscape occupied by “savages,” the grid became a tool of settler colonialism in its attempt to dominate land that did not belong to them. Furthermore, the grid’s straight repeated lines—a declarative and predetermined cartography—illustrate power’s resistance to discomfort, surprise, and uncertainty by its elimination of difference. Anyone who did not capitulate to this form could be cast as a renegade and improper—even wild. Its straight lines also facilitate clear sight lines which, as Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon illustrates, can in themselves pacify bodies into obedience through a persistent assumption of being visible and therefore watched.

It is a challenge, then, to put oneself out of view in the grid, to resist visibility, without the risk of being othered and turned into an object. The modern surveillance state has turned our spaces into a grid writ large and has made invisibility, in this sense, almost impossible. As a result, we have all been objectified in a way—though some more so than others. But how often is surveillance’s omnipresence, whether the literal vectors of security cameras and their phenomenological effects on individuals moving through space (stress, fear, etc.) or simply as a quality inherent to the grid, incorporated into architecture renderings?

“If there’s a reliance on the truth of the line, how do we subvert that in some ways? Is it something about a density of marks? Redaction? A lack of visibility? A refusal of interpretation? Whether it’s fine to be oblique and not communicate? How do we layer the accretions of time, the fluidity of movement, its staccato rhythms, in the space of the drawing?” asks Newsom. Her students’ translations of their walks suggested novel responses to these questions of representational possibilities and limits in drawing. “Some are developing a kind of notation, almost like Laban dance notation, in which they make correspondences between movements and marks,” she says. “Others are looking at stereoscopic vision—the fact that we have two eyes. Those students did an interesting animation which explores moiré effect and the way in which our eyesight involves light hitting two receptors and the brain processing it in order for us to understand the three-dimensional world.”

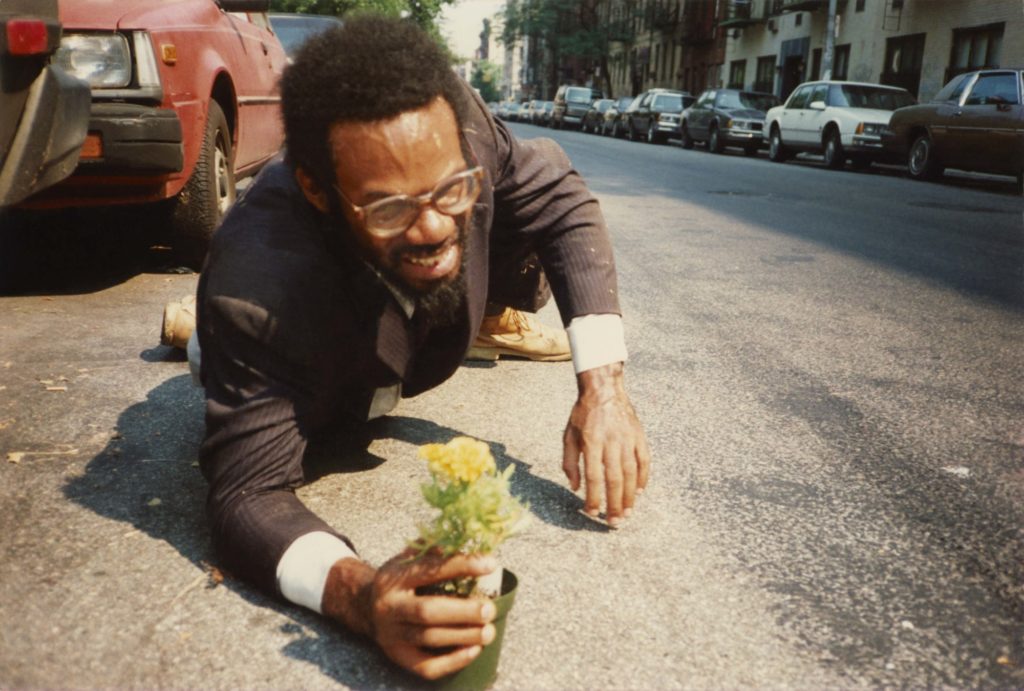

As a further effort to inspire alternative possibilities in representation, Newsom then asked students to engage with a diverse group of artists whose work challenges hegemonic flows through movement, film, dance, and photography, as well as drawing. For example, for decades, the American artist William Pope.L performed long-distance crawls throughout New York City and Europe. In Tompkins Square Crawl (1991), he wore a business suit while carrying a small potted plant, as if he were on his way to work. The piece illuminated that just to crawl—to refuse walking, verticality, and thus the dominant point of view and means of mobility in society—was enough to disrupt, to draw attention, and even to have movement stopped. In fact, an onlooker became so irate that he called the police.

Renée Green also plays with our ability to ignore the visible in her 1992 work Mise-en-Scène: Commemorative Toile. By appropriating the 18th-century toile fabric tradition, which was produced by colonized peoples and often depicted colonizers and the colonized alike in bucolic scenarios, Green comments on Empire’s violence and its effacement of the Other. From a distance, Green’s delicate floral patterns seem to preserve toile’s traditional pastoral peace. Upon closer examination, however, one sees the lynching of a Frenchman, an enslaved Black man chained and kneeling in front of a white man, and other brutal scenes. The work could be read as a castigation of actions that purport to acknowledge problems but suggest no systemic changes—literal window dressing that asserts surfaces’ capacity to preserve power and the need for change to be more than skin deep.

Conversely, Janet Cardiff engages with the non-present and invisible in the scripted, choreographed walks she produces with George Bures Miller, such as Night Walk for Edinburgh (2019). Participants are guided by Cardiff’s voice through headphones from which myriad street noises also emanate as they follow a prescribed path through the city. They hold smartphones which play scenes from a film shot on the same streets they traverse—a woman running down an illuminated path; drunk men singing as they pull a man, perhaps dead, on a trolley—creating a kind of augmented reality. Cardiff describes the experience as similar to that of recalling a dream when you wake up, with various scenes and characters that you might remember in full or just in pieces.

By incorporating a sense of play into these interactive performances, and paradoxically through the use of technology, Cardiff compels us to pay closer attention to our physical environments, and specifically to absences therein. Through the haunted and haunting medium of film, she makes explicit that our environments are archives of memory and receptacles of loss. From a design perspective, her films prompt questions regarding the acknowledgment of time passing, such as the continual attempts to erase historical memory through repairs of surfaces as opposed to allowing them to reflect the passage of time. They also examine the continual attempts to erase such memory through repairs of surfaces, as opposed to allowing these surfaces to reflect the passage of time.

In part due to film’s incorporation of time—which separates it from drawing—Newsom assigned students to synthesize what they learned from their earlier explorations by creating short films using their own prompts, with a maximum length of three minutes. “In my practice, we do a lot of collaborations with filmmakers as a way to help us reinterpret, more deeply understand, and interrogate our work, but much of that happens after our installations are built,” she says. “I was interested in seeing what would happen if film is foregrounded in the architectural process, in what ways it could comment on how we represent, say, weight, slowness, effort, or exertion, and how those actions interact when executed in space as well as how others react to them.”

With these varied exercises Newsom hopes to inculcate a heightened awareness of the unconscious and conscious attitudes and tools that students bring to their work. “This is one of the last advanced studios for students before they do their theses,” she says. “They’ve been given an inheritance through their education to this point, and I’m asking them to think about what they do with it.” This “inheritance” is akin to Marx’s theory of history. “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past,” he writes in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. “We’re all physically in the world and are taking in the directness of experience in the moment, but we also bring our inheritance with us into those spaces,” Newsom continues. “Operating as a designer is no different. There’s a physical reality of what you’re creating but there’s also the intention that you bring to it and the inheritance that it carries with it before you’ve even arrived. There are physical and material realities of the world and conventions in which we operate, but the question is how we work with, alongside, and against them.”

It would be too idealistic to say that we can refuse the gifts of inheritance. Resisting and transgressing the expectations of the gift giver, however, is a conscious act, and an act that we ignore at our peril.