Students, Faculty Receive 2021 Harvard Mellon Initiative Awards for Urban-Focused Research

Students, Faculty Receive 2021 Harvard Mellon Initiative Awards for Urban-Focused Research

The

Harvard Mellon Urban Initiative recently awarded 29 grants for urban-focused research projects undertaken by Harvard University undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, and fellows. Of the 2021 grantees, four are affiliated with the GSD:

Adriana David Ortiz Monasterio (MDes ADPD ’21),

Steven Gu (MUP ’21),

Thomas Shay Hill (PhD candidate in Urban Planning), and Assistant Professor of Urban Design

Charlotte Malterre-Barthes.

Part of HUMI’s larger initiative to advance cross-disciplinary approaches to urban studies, the program seeks to sponsor “sustained research projects that incorporate new visual and digital methods in the study of urban environments, contributing to the Harvard curriculum, producing publications and exhibitions, and generating a wide variety of urban studies programming and community-building,” according to its

press release.

Adriana David Ortiz Monasterio (MDes ADPD ’21)

David’s project,

The Architecture of Food Sovereignty, investigates “the Milpa”—companion crops essential to the Indigenous cultures of North America. “This project will look at the evolution of Milpa’s supply chain for the Mexico City area, from precolonial times, until today. It intends to expose the land they are grown in, the seed variety used, the type of agriculture employed, the cycles needed, the industrial process, the packaging, the storage, the transportation and the final process for consumption in order to reveal the main reasons for today’s urban food instability,” writes David in her project statement.

Steven Gu (MUP ’21)

Gu’s HUMI grant was awarded for

The Right to Consume: Human Rights, Protest, and Commodities in the Built Environment. With this project, Gu aims to “document and delineate the negotiation of protest movements, spaces of consumption, and role of commodities in the built environment. The research will focus on three cities: Hong Kong, Bangkok, and Philadelphia. Each case study will highlight how civic demonstrations engage with urban spaces planned for consumption.”

Thomas Shay Hill (PhD Candidate)

by Hill will “use GIS and other computational approaches,” in order to “synthesize historical datasets with archival material to visualize the urban transformations wrought by successive phases of intense development and contraction.”

Assistant Professor of Urban Design Charlotte Malterre-Barthes

The project

Material World from Malterre-Bathes looks to “engage in understanding the ways that design disciplines intersect with territories of extractivism and resource exploitation, and how seemingly irrelevant composition details fit in the global enterprise of ‘extractive neoliberalism’ that fuels injustice, social struggles, and climate change.”

Read more about these and other HUMI funded projects. LA DALLMAN Architects wins 2021 Progressive Architecture Award for transformation of 1901 Wisconsin grain elevator

LA DALLMAN Architects wins 2021 Progressive Architecture Award for transformation of 1901 Wisconsin grain elevator

The transformative new design for the Teweles and Brandeis Grain Elevator in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin by

LA DALLMAN Architects, the firm of

Grace La (MArch I ’95) and James Dallman (MArch ’92), is one of six projects honored with a 2021

Progressive Architecture Award by

Architect magazine. Now in its 68th cycle, the annual awards recognize innovative unbuilt projects, with this year’s awardees celebrating “architecture in service of the greater good.”

“This project shows how the structures that dot the landscape and are inherently recognized by us as a certain typology could be transformed for reuse, recognition, and a sense of place,” explains juror Daimian Hines, who was joined on the jury by GSD Professor in Practice of Architecture

Jeanne Gang and Koray Duman.

At the GSD, La is professor of Architecture, chair of the Practice Platform, and former director of the Master of Architecture Programs. She is currently teaching the option studio “

BRIDGE WHERE YOU ARE: The Anamorphic Double” and previously led an

option studio with Dallman in the spring of 2019.

Built in 1901, the harbor-front Teweles and Brandeis Grain Elevator was decommissioned in 1960 and sat idle for the next 50 years. When it was facing demolition in 2018, a campaign to save the structure led to the involvement of LA DALLMAN Architects and its engineering team. With strategic subtractions and additions to the utilitarian structure, their adaptive reuse design reimagines the site as a new performance space and tourist destination.

As part of the P/A Award, the Teweles and Brandeis Grain Elevator project is featured on the cover of Architect magazine’s March 2021 issue.

“Along with our client and engineering team, we are honored to receive such important recognition for this project. It epitomizes the potential of public spirit and catalytic, civic space,” says Dallman. “It is not often that a community-driven rehabilitation of an historic structure receives a PA Award, and that makes this very special for everyone involved. It suggests a more layered and transformative approach to design.”

Learn more about the project.

Harvard GSD announces Harvard Design Press

Harvard GSD announces Harvard Design Press

Harvard Graduate School of Design is pleased to announce

Harvard Design Press, a book-publishing imprint based at Harvard GSD and distributed in collaboration with Harvard University Press. Harvard Design Press challenges, broadens, and advances the design disciplines and advocates for the value and power of design in making a more resilient, just, and beautiful world. In pursuit of new, original ideas on the research and practice of architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning, and urban design, the Press seeks book proposals from researchers, practitioners, theorists, historians, and critics, among others. More information about submitting a proposal can be found on the Press’s

webpage.

“Long committed to the value of the written word for advancing the design disciplines as well as for broadening design’s impact, I am personally very excited about this new direction for the school’s book-publishing program,” says Harvard GSD’s Dean Sarah M. Whiting, who serves as a member of the Harvard Design Press Editorial Board. “I look forward to the great work that will come of it.”

Harvard Design Press plans to publish its first titles in Fall 2022, beginning with a monographic book featuring the work of architect Frida Escobedo, titled

Split Subject. Split Subject unpacks an early project of the same name, one that deconstructs a fraught allegory of architectural modernism in Mexico and that has exercised enduring and formative influence throughout Escobedo’s career and practice.

Harvard Design Press is organized and edited by Harvard GSD’s Ken Stewart and Marielle Suba, and guided by an Editorial Board composed of Harvard GSD and Harvard University faculty. Alongside Dean Whiting, the Harvard Design Press Editorial Board includes Harvard GSD’s Martin Bechthold, Anita Berrizbeitia, Eve Blau, Ed Eigen, K. Michael Hays, Niall Kirkwood, Mark Lee, John May, Rahul Mehrotra, Erika Naginski, Jacob Reidel, and Sara Zewde, as well as Harvard University’s Lizabeth Cohen, Sarah Lewis, and Patricio del Real.

To learn more about Harvard Design Press and explore submission guidelines, please visit the Press’s

webpage. To stay up-to-date on new releases and general Harvard GSD news, please visit Harvard GSD’s

homepage and subscribe to its Design News updates.

Can Parkitecture Heal? Jeanne Gang on making American National Parks “more accessible, more inviting, and more welcoming”

Can Parkitecture Heal? Jeanne Gang on making American National Parks “more accessible, more inviting, and more welcoming”

Early federal policies that set aside land for the national parks focused mainly on the preservation of objects with “historic or scientific interest.” Protections against incompetent archaeologists and unscrupulous resource speculators encoded in the Antiquities Act of 1906 were essential and powerful safeguards of the public interest. Later legislation expanded these protections and, crucially, provided for the public “enjoyment” of federal lands. With its emphasis on recreation, the founding of the National Park Service in 1916 officially oriented the parks to the people. While they had long been places of contemplation, enjoyment, and solace, Title 16 made the parks a manifestation of the nation’s humanity, and a legacy to be preserved “unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” But in the early 20th century, many of the national parks were remote and difficult to get to, making them accessible only to the ruggedly independent. This has changed, of course. The National Parks recorded 237,064,332 recreational visits in 2020, which entailed more than a billion hours of enjoyment.

By facilitating and framing visitors’ experience of nature, architecture and landscape architecture have played a significant role in the rising popularity of the national parks. The familiar, rustic style of architecture developed for the national parks is one of the most visible legacies of the New Deal of the 1930s. During that era, the National Park Service established high standards for construction of roads and trails, placement of viewpoints, and provision of park amenities. The 120,000 employees of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) provided a workforce to complete the job. Not only did the program offer young unemployed laborers productive work, it did the parks “immeasurable good,” according to then parks director Arno Cammerer. CCC roads, trails, visitor centers, lodges, and picnic shelters greatly improved access to the parks.

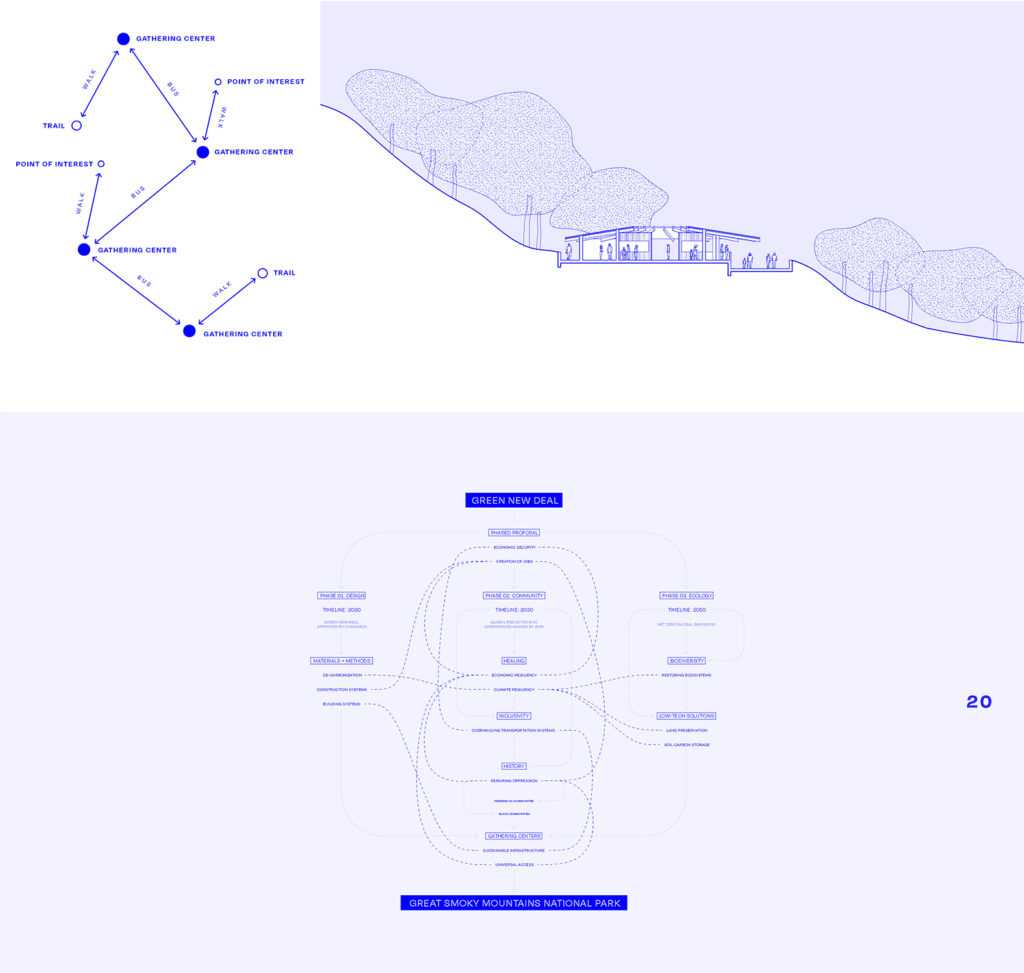

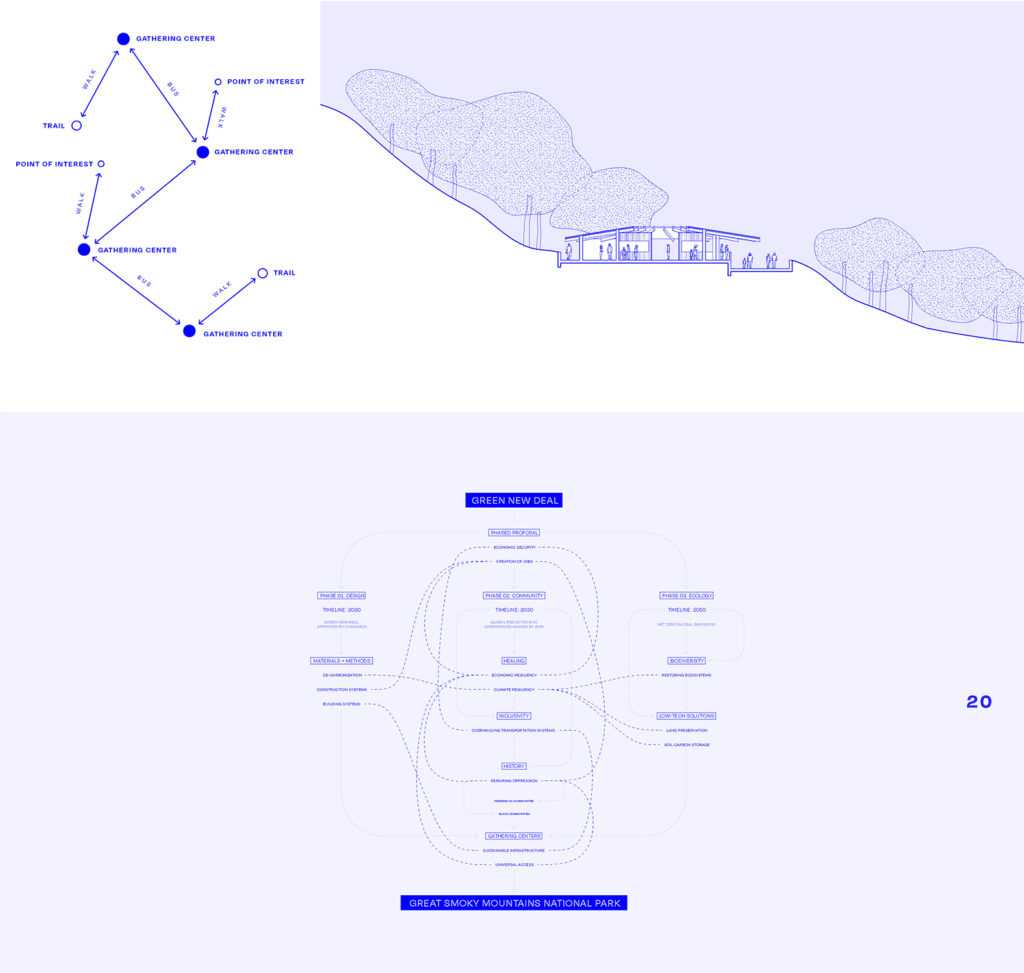

While a single building cannot heal racial and climatic crises, architectural processes—construction methods, material ethics, and project phasing—can effect institutional change and promote justice.

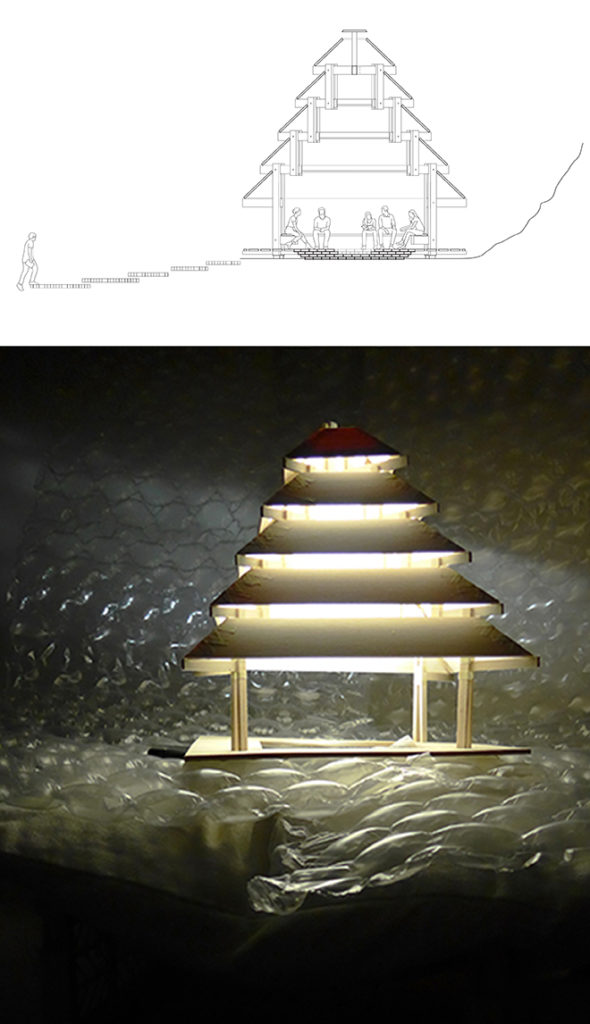

Stephanie Lloyd (MArch ’22) and Ada Thomas (MLA ’21)on their proposal for a distributed system of gathering centers integrated into the park’s ecological systems for “Can Parkitecture Heal?”

At the same time, the park architecture—based largely on late-19th-century principles of Andrew Jackson Downing, the Olmsteds, and the arts and crafts movement—became widely familiar. The craggy masonry, rugged carpentry, and simple forms seem naturally compatible with the wild settings of the parks. American “parkitecture,” as it is often known, is deeply appealing, almost symbolic of vacationing, adventure, and enjoyment of nature. It also recalls the social contract of the New Deal—park construction helped raise thousands out of poverty after the Great Depression.

However, even as the parks welcome millions of visitors, not everyone feels equally at home in them. As GSD

Professor in Practice Jeanne Gang and Instructor Claire Cahan point out in the brief for their Autumn 2020 studio, “Can Parkitecture Heal?,” the legacy of the parks is not all positive: “While these places and their beneficial qualities are intended to be accessible to everyone,” they write, “the parks continue to struggle with inclusivity and their histories of racism, including displacement of Native peoples and segregation.” Rustic park visitor centers and other facilities offer easy, welcoming access to many people; however, for others the close symbolic association of parkitecture with the history of the parks can tie it just as closely to these social ills. A central challenge of the studio, then, was to seek ways to “redefine” parkitecture, Gang explains, and to make park buildings “more accessible, more inviting, more welcoming.”

The studio focused on Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the most frequently visited park in the system. A regular flood of visitors puts immense pressure on the park facilities, and its two aging visitor centers have become inadequate. More critical, Gang emphasizes, is that even though the park is close to some adjacent towns that can bring in more a diverse population, there is not much programming to introduce the park to people who would not normally visit. Park Superintendent Cassius Cash, who met with the students early on, has begun to address this problem. He recently inaugurated Hikes for Healing, a program which brings visitors from local communities to enjoy the park while working with a moderator to discuss persistent social conflicts that deeply affect them—and the nation—in a time of strife: “The Smokies Hikes for Healing (SHFH) initiative is designed to use Great Smoky Mountains National Park as a place of sanctuary… where crucial conversations about race will occur in one of the most diverse ecosystems in the world.”

Gang and Cahan challenged their students to consider this type of cultural programming while designing park facilities. They asked students to think about events that might broaden the park’s appeal, particularly to those who do not generally turn to nature for enjoyment and solace. “The way it is presented in the park, nature is culture,” Gang emphasizes, “so bringing more kinds of culture into the visitor center site” gives people a chance to come in and participate in the storied “healing experience” of nature. Accordingly, the studio’s building program included a new visitor center and a “gathering pavilion” for the SHFH hikes. The studio brief also proposed that these new buildings would share a site with the Sugarlands Visitor Center, which would be remodeled as “an interpretive exhibition hall,” to form a “renewed park village that retains the past and introduces new types of spaces for learning, gathering, and healing.”

View of Sugarland Visitor Center, 1964. Courtesy of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

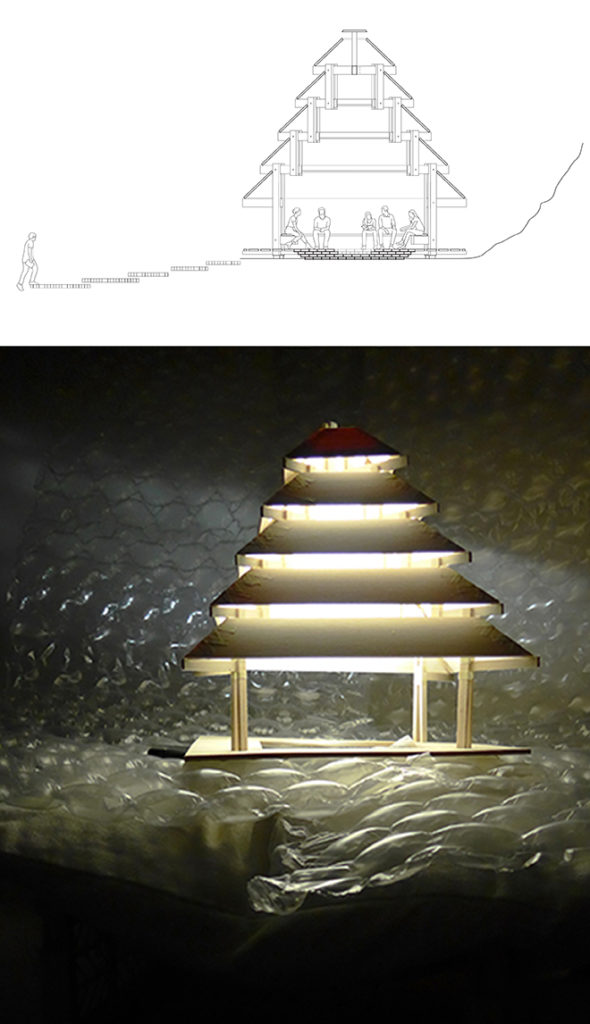

The students addressed the gathering pavilion first, developing a range of solutions that included primordial elements of shelter, open air, and fire but that also proposed novel details. In some cases, Cahan explains, “part of this idea of healing and coming together was to physically operate the building.” In other words, the pavilions would function not merely as spaces for gathering, but as mechanisms to bring people together.

Images by Audrey Haliman.

In developing proposals for the new visitor center, the students continued to explore architecture’s capacity for healing while extending their concern into other consequential issues. As participants in the national

Green New Deal Superstudio, the GSD studio members also considered architecture’s capacity to take on the global challenges that are central to the 2019 Green New Deal legislation: “

decarbonization, justice and jobs.” For the “Parkitecture” studio, this was a natural fit.

Acknowledging the lasting manifestations of the New Deal in CCC-built park facilities, they asked themselves how the Green New Deal could similarly advance the role of architecture in causes vital to our own era. In particular, the Superstudio calls for designers to “meaningfully engage in a response to the climate crisis at local, regional, and national levels” by reexamining “their roles in civil society and lead a national conversation about the nation’s future at a critical time in history.” Gang recalls, “One of the students said something really interesting, which was: Those issues are so big, and the studio felt like a way that one could use one’s skills as a designer to address them in a direct way that could make a difference—just a small step. . . .” In addressing these big questions, the students focused on effective programming, small-scale design, and careful detailing.

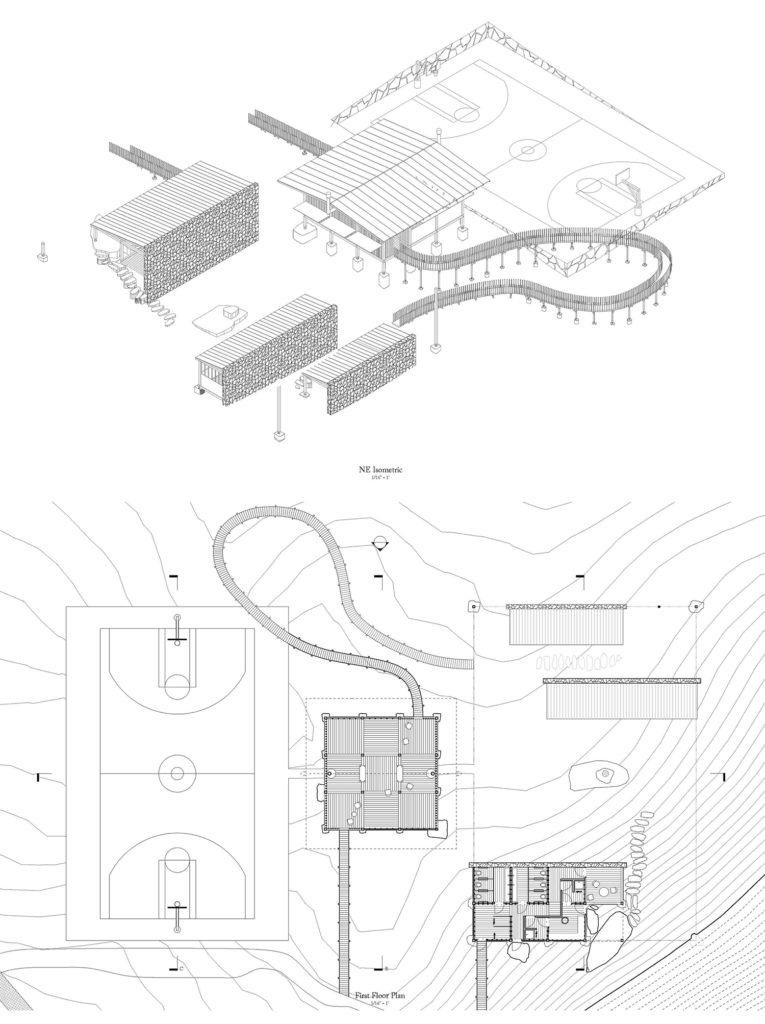

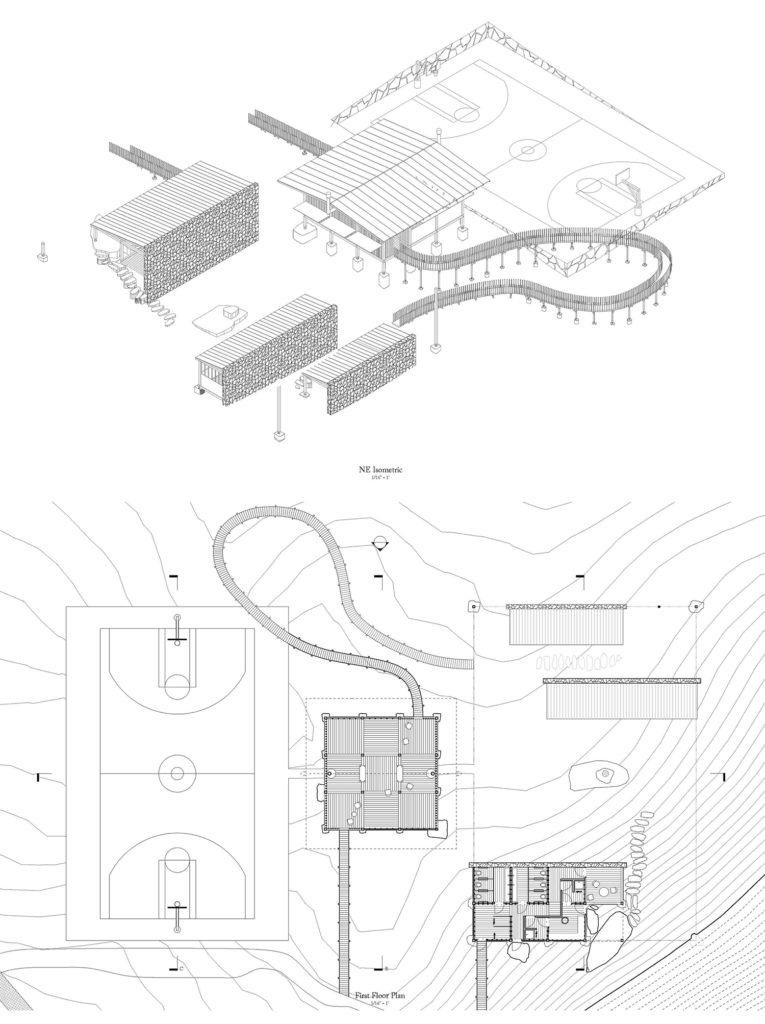

Each of the six pairs of students emphasized the potentially great consequences of small-scale work. For example, Jack Rodat (MArch ’22) and Nima Shariat Zamanpour (MArch ’22) proposed “distributed interventions” that expand “the narrative of the park by highlighting an observed contradiction”—a classroom in the trees, a composting facility with welcoming signage, a fireplace gathering center, and a basketball court. They write, “Just as the Green New Deal tethers seemingly distinct issues of jobs, justice, and decarbonization together, we believe this multifaceted approach is necessary in the design of the new visitor experience at Sugarlands.”

Images by Nima Shariat Zamanpour and Jack Rodat.

Stephanie Lloyd (MArch ’22) and Ada Thomas (MLA ’21) proposed a distributed system of gathering centers carefully integrated into the park’s ecological systems. Their construction would use selectively removed trees as the formwork for labor-intensive, low-carbon rammed-earth walls. “While a single building cannot heal racial and climatic crises,” they explain, “architectural processes—construction methods, material ethics, and project phasing—can effect institutional change and promote justice.”

Images by Ada Thomas and Stephanie Lloyd

Just as “America’s best idea” began with the preservation of artifacts, a new approach to big societal issues through design must begin with small-scale efforts. As ambitious as the Green New Deal Superstudio is, the participants in the GSD’s “Parkitecture” studio found that if architecture is going to contribute to healing it must do so at a human scale.

Faculty-led Stoss Landscape Urbanism tapped to develop Boston’s first Urban Forest Plan

Faculty-led Stoss Landscape Urbanism tapped to develop Boston’s first Urban Forest Plan

Stoss Landscape Urbanism, the design studio founded by

Chris Reed, has been selected to develop Boston’s first

Urban Forest Plan in collaboration with forestry consultant Urban Canopy Works. The effort will establish a 20-year canopy protection plan for the city and address topics including ecology, design, policy, environmental injustice, and funding.

In addition to his role as founding director at Stoss, Reed serves as professor in practice of landscape architecture and co-director of the Master of Landscape Architecture in Urban Design program at the Graduate School of Design. His colleague

Amy Whitesides (MLA ’12), director of resiliency and research at Stoss and design critic in landscape architecture at the GSD, will lead the effort for the studio.

“Our job is to fuel the project’s success by coordinating efforts between all the partners who each bring their own unique expertise,”

explains Whitesides. “The ultimate goal is to maximize the health of Bostonians and their environment. We’re proud to work with the City of Boston on this shared commitment to Boston’s Urban Forest Plan.”

The project will consist of scoping and assessing the existing state of Boston’s tree canopy while developing a plan to engage the community. Since tree removals on residential, private, and institutional properties have been the main contributors to canopy loss in the past five years, the Urban Forest Plan will also highlight policy tools to expand canopy on public streets and parks and control future loss on private property. The planning process will kick off in the spring of 2021 and will take approximately one year to complete.

Boston Mayor Marty Walsh says that the Urban Forest Plan will “ensure our tree canopy in Boston is equitable, responsive to climate change and ensure the quality of life for all Bostonians.” He also emphasizes the importance of community input so that “residents in our neighborhoods have a central voice in this process.” Commissioner of Parks and Recreation Ryan Woods adds, “It’s no coincidence that many of the communities disproportionately impacted by poor air quality and the urban ‘heat island’ effect, also have inadequate tree cover. We’re excited to collaborate with these partners to find opportunities for growing tree canopy in the places that need it most.”

Read more about the Urban Forest Plan on the

City of Boston’s website and in

World Landscape Architecture. Excerpt from Pairs Issue 01: “On the Foundational Spirit: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits” by Sara Zewde with Kimberley Huggins

Excerpt from Pairs Issue 01: “On the Foundational Spirit: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits” by Sara Zewde with Kimberley Huggins

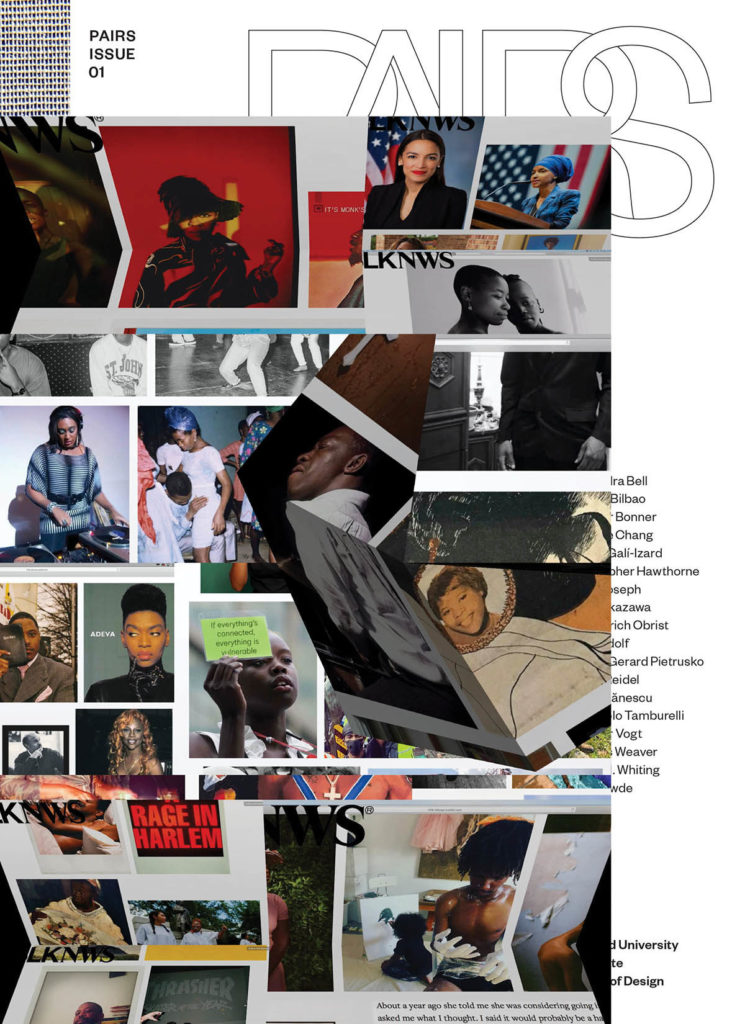

Pairs

Pairs is a student-led journal at the Harvard Graduate School of Design dedicated to conversations about design that are down to earth and unguarded.

Each issue is conceptualized by an editorial team that proposes guests and objects to be in dialogue with one another. The following is an excerpt of a conversation from Issue 01 between

Pairs co-founder Kimberley Huggins (MLA I ’20) and Sara Zewde, Assistant Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, titled “On the Foundational Spirit: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits.”

KIMBERLEY HUGGINS So,

“Cotton Kingdom, Now”: your return to and inaugural class at the GSD!

Your class is occurring during a time when the dominant narratives of history and their intended values are being seriously questioned. In the context of the education of landscape architecture, this sentiment often materializes in the student body as a desire to toss the canonical history and start anew. Students struggle to see how it is equipping them in the face of contemporary social and environmental realities. Subsequently, there is a desire to excise it. It is not uncommon to hear students say, “I do not want to hear about Olmsted anymore. I do not want to talk about gardens anymore.”

And so while many are asking for the focus to be moved from Frederick Law Olmsted with a belief that the more relevant lessons are elsewhere, what was it that drew you in further to focus on his time as a young journalist?

SARA ZEWDE The landscape architecture that is taught at the GSD now is significantly different than the landscape architecture I learned when I started in 2011. Even a comparison after a few years is mind-boggling. Things are rapidly changing and it is not like that change

started in 2011. When I speak with students who studied before me, it becomes clear that there have been a number of significant shifts within the last 15 years in landscape architecture education.

I don’t think there was a single Black person referenced in my three years of landscape architecture education. Be it in a syllabus, a chance to read their writing, to learn about their thoughts on the world, or to study their projects as precedent. On the other hand, there were many slave holders celebrated. Thomas Jefferson was presented unproblematically for his brilliant innovations in landscape design. And so I was perpetually, in those three years, very lost about my place in this profession. In fact, I took a year off and went to work for

Walter Hood and came back having more confidence in my ability to see myself in this profession and understanding about how my experience in the world can influence design. Because, otherwise, when I would ask certain questions in school, it was often met with, “You’re in landscape architecture; why would you bring that up?”

In my third year, we had a guest lecturer in our “Professional Practice” class who, in passing, mentioned that Olmsted visited the South. That was the first I had ever heard of that. We had already learned a lot about Olmsted, but I had never heard that he traveled through the South to write about the conditions of slavery. I followed up with the guest lecturer, and with my two professors—I still have this email. I often revisit that email chain because it has led me to this point in my research. I asked for further reading material about Olmsted’s travels and they sent me a reference, but what I really wanted was to be able to reflect on the connection between his abolitionist thoughts and his practice of landscape architecture.

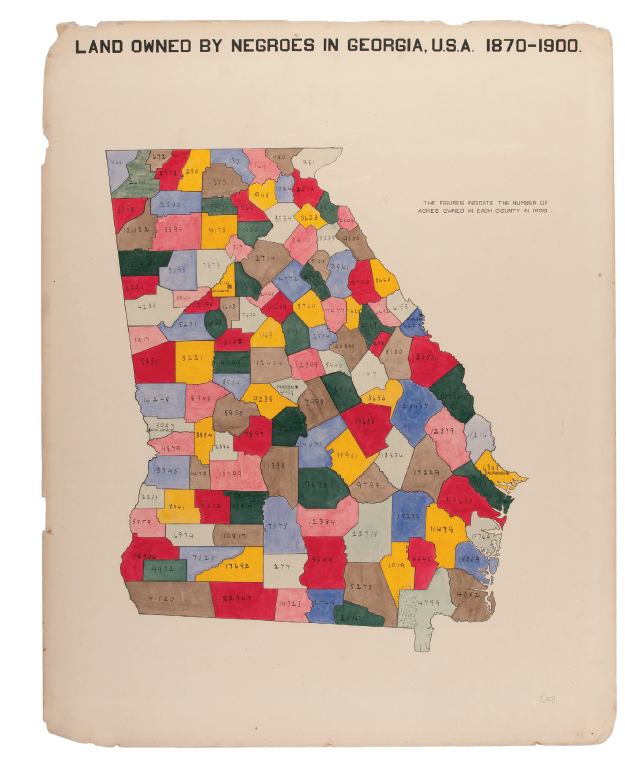

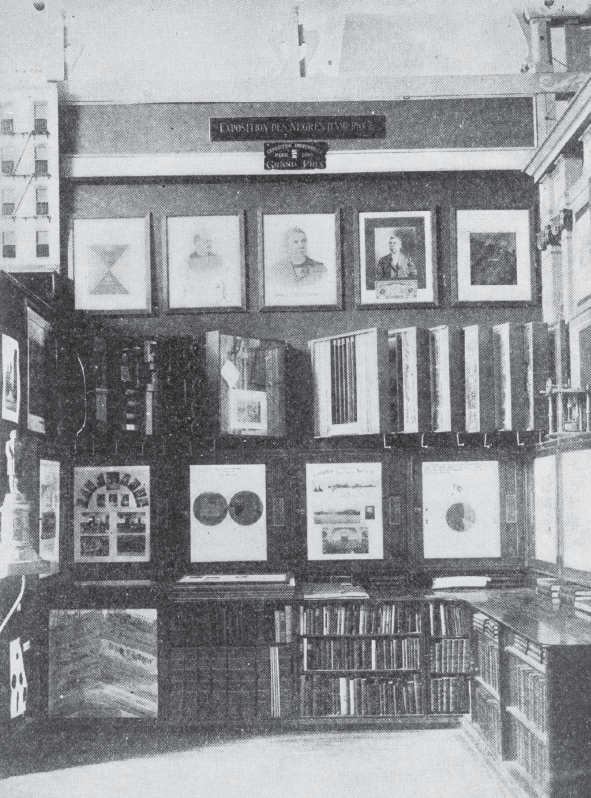

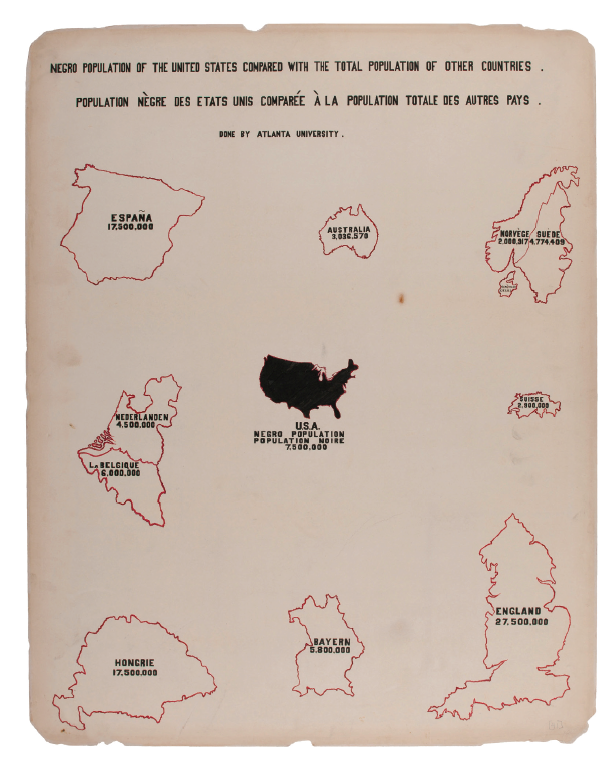

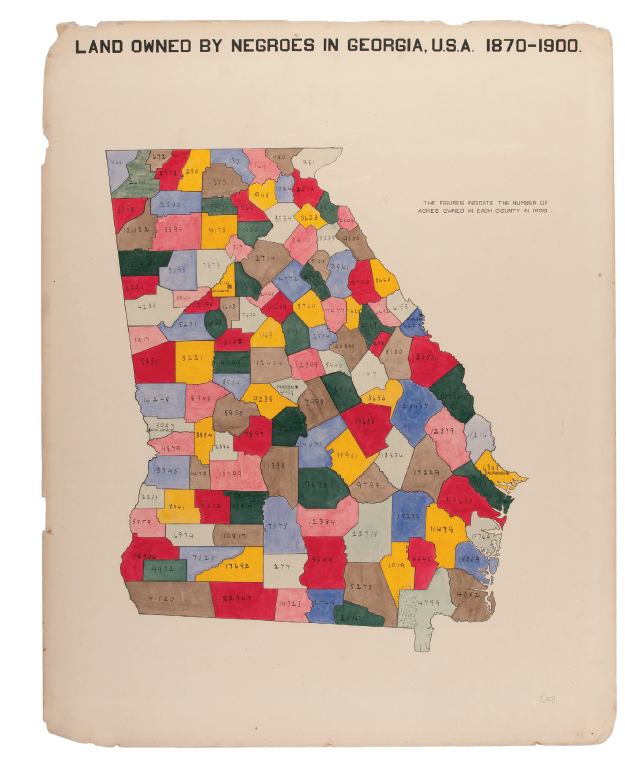

A photograph of W. E. B. Du Bois’s “Exhibit of American Negroes” for the 1900 Paris Exposition.

If that book had existed, I would have read the book and kept moving on with my life. But it didn’t exist and I couldn’t resolve the fact that this had never been brought to my attention, and how much we could possibly learn from mining this part of Olmsted’s biography.

So, I got a fellowship and spent four months at Dumbarton Oaks researching this. After that, I spent three months in a car retracing his steps through the South. I proposed, as part of my research methodology, that visiting the sites would offer some reflections on the relevance of Olmsted’s travels and the profession today. Now, I’m writing those reflections into a book.

The seminar I am teaching this semester investigates Olmsted’s original writings on the South not only as a historical document, but as a methodological proposition. The students develop research and representational methods to make assertions about the factors underlying the change witnessed on the site over the course of the past 165 years, since Olmsted’s visit.

Because ultimately, I think Olmsted’s story has implications for what our practice of landscape architecture can be today. I think that looking at the places he visited and taking stock of the changes they’ve undergone, as well as the ways they’ve stayed the same, presents opportunities for considering the potential of contemporary landscape architecture and methods.

KH There is a persistent question of relevance felt within the field, and maybe even perceived by outsiders, but in either case, it is not always clear what our fundamentals are. What has researching the methods used by Olmsted prior to entering landscape architecture revealed to you about our foundations, and why should this text be a grounding force in contemporary landscape architecture?

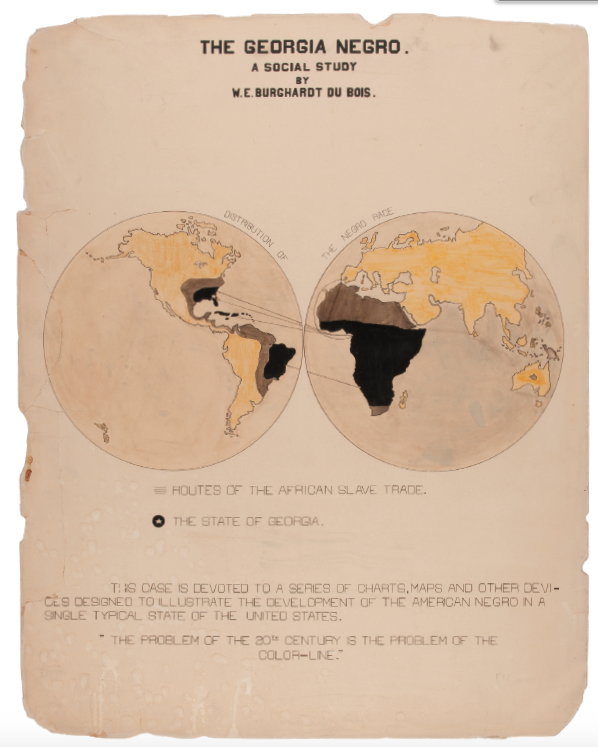

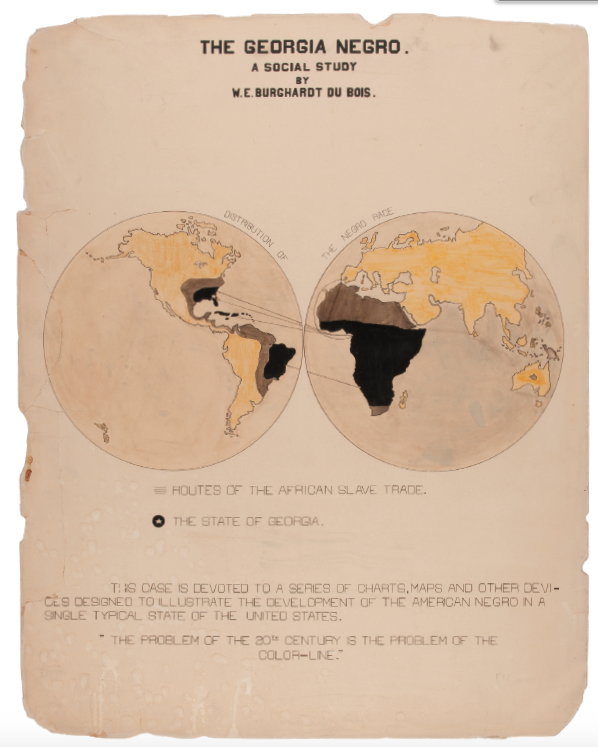

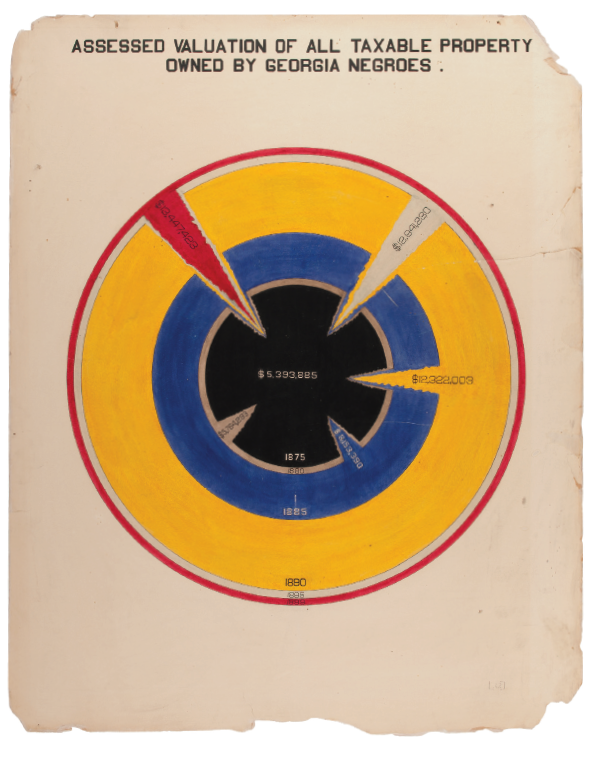

W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Visualizations of Black America, The Georgia Negro: A Social Study.

It actually starts with challenging the idea that this was something that he did before landscape architecture. What my research is revealing to me is that they were actually simultaneous endeavors in a way, not subsequent to one another. In fact, he steps down from his position as superintendent of Central Park in order to rewrite his work about the South and republish it. It is not a fair portrayal of Olmsted to hold these endeavors of his separately.

What was powerful about Olmsted, and can be seen in this text, was his way of being able to toggle between a site and into its larger economic, social, and ecological dynamics. We have hundreds of pages of Olmsted in conversation with enslaved people where he took extra care to record dialect. He takes great care to record details of light qualities, topography, tree species, and soil conditions. He was very tuned into the here and now, and at the same moment, engaged in analysis of the underlying macroeconomics, macropolitics, and macroecologies of each place. This carried forward into his practice of landscape architecture where he thinks in a very material way, but always in the context of the wider concerns of society.

Something happened in the transition from Olmsted Sr. to the next generation of landscape architects. The wider range of concerns fell away and the idea of landscape architects as technicians took hold essentially. The reality is that shaping landscapes is a very powerful tool. To wield that power without an understanding of the larger context or an acknowledgement or sensitivity or methods, there’s a lot of damage that can be done. It’s an incredible power, right? We have decades of landscape architecture, architecture, and urban planning that demonstrate what kind of damage can be done if you don’t have the proper methods or considerations. So, it’s interesting to see how landscape architecture is grappling with its relevance in these contexts of late, whether environmental, ecological, social, political, or economic. Some of the answers may be found in the origin story of the profession, if we claim

The Cotton Kingdom as part of it, as I aim to do with my book.

I’m perplexed as to why landscape architecture has avoided historicizing this text as part of its origin story. In fact, landscape architects often reference

Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England, which predates

The Cotton Kingdom. So, you could argue it’s less relevant to Olmsted’s practice of landscape architecture, but it’s in England, so maybe that is easier to talk about, if you assume that’s why. But I will say that among historians, Olmsted is considered the most cited witness of slavery in the 19th century. There’s no doubt about the significance of Olmsted’s writing in the South in history. It is landscape architects who are kind of quiet about it.

KH It was so surprising to find that Malcolm X cited this writing as one that was influential to him. This idea that a landscape architect could create anything that would be found relevant to someone like Malcolm X is incredible.

SZ Yeah! Like, Olmsted might have sparked the career of one of the foremost activists in the civil rights era? What?

KH Yeah, unbelievable.

SZ Without Olmsted, we may not have had an awakened Malcolm X to spark Black nationalism and all of these important Black philosophical frameworks.

KH But now, we just pass over this book. When you consider that the field never truly embraced this writing, even from a canonical figure like Olmsted, but did embrace writings that termed the field as being one of, “the polite arts,” like Humphrey Repton’s

Art of Landscape Gardening, for example, it produces a jarring realization about our blind spots; the parts of our history that we’re able to handle and that which we are not.

SZ Yeah, exactly. The English were a major part of the transatlantic slave trade. Where was all that capital coming from that would fuel the Picturesque movement? Because the Picturesque was all about labor and this dominion over the landscape that slavery was honestly a major driver of. And so to me, you can’t separate all of these movements in Europe from the history of slavery, dispossession, and colonization.

KH In

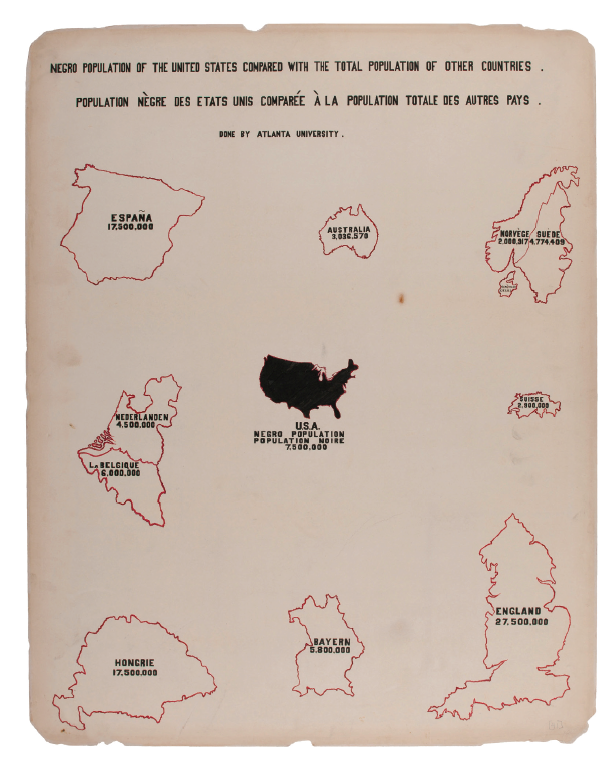

The Cotton Kingdom, there is one map that takes what is otherwise an argument made in a long and complex text, and summarizes the research as simply and succinctly as possible through its spatial reality. It illuminates connections. How might this drawing stand in relation to the data portraits of W. E. B. Du Bois’s Paris Exhibition of 1900? Both of these documents together convey some sense of the realities in the United States immediately before and 37 years after abolition. There is a lot that can be said about these documents that is difficult in such a short time, but broadly, what does the pairing of these drawings make you think of given your research, your practice, and your background in sociology?

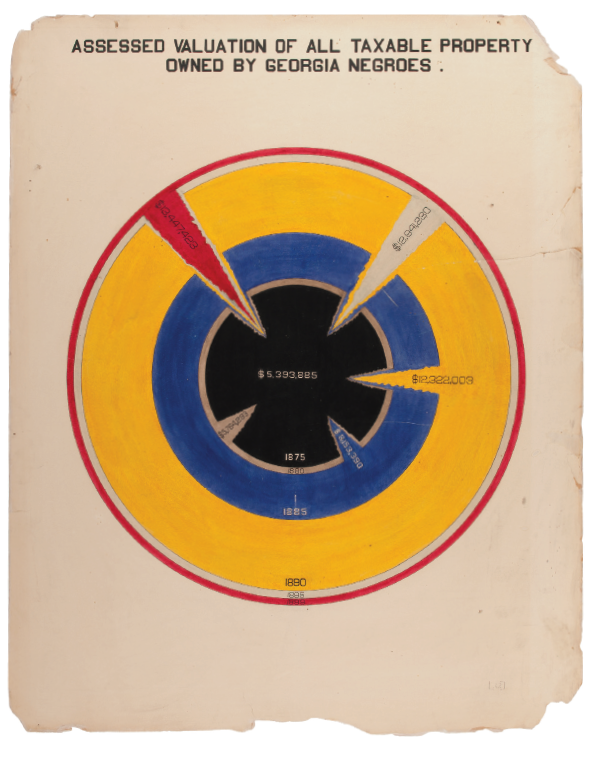

Assessed Valuation of All Taxable Property Owned by Georgia Negroes.

One thing that we’ve been talking about in class is the idea of both representivity and singularity. Black literature in the United States is really birthed in the idea of the slave narrative and people writing their personal experiences of being enslaved. We just read a Toni Morrison essay called

“The Site of Memory,” where she explains the challenge of Black literature, which is to both express and articulate the specifics, the singularity of experience: “This happened to me. This is my story.” But at the same time as they’re expressing their singular experience, these authors would try to reflect a representivity. In other words: “This is happening to me, but imagine the scale at which this is happening to other people—millions of them—broadly, who are enslaved and/or oppressed.” It was always a dual mode in which they wrote.

Olmsted and a man named Daniel Goodloe made the map you are referencing to be included in the third publishing of the writings, which was his most staunchly abolitionist editing of the work. The book is structured with the large macro-conclusions as bookends to the travel notes in the middle chapters. The travel notes are all about that singularity: I went here. I had this conversation.

This site, this site, this site. But then the intro and the conclusion chapters are about that representivity, making large-scale analyses of the region. This map is included in that.

Du Bois too. Du Bois has these sociological studies where he spends time in a very specific Philadelphia neighborhood, for instance, and is doing very similar qualitative analysis of singularity, but at the same time is toggling out to this sort of representative mode of working, which his drawings reflect.

And so both Olmsted and Du Bois are grappling with the productive space between representativity and singularity. That is, in my mind, one of the biggest takeaways for landscape architects whereas we generally work more exclusively in the singular, site-scale mode. Both Du Bois and Olmsted work between the two as social scientists, designers and journalists, but are also evolving those methods. It’s interesting. It’s compelling to pair the two in that way.

KH I’d also like to point out that you share this point of comparison with the two. Du Bois was, among many things, a social scientist; Olmsted operated as a social scientist; and you yourself have a background in sociology and statistics prior to entering design. What was it that sparked this transition in you?

SZ Yeah, I’m realizing that’s not very common. Most of my friendsand colleagues entered into design from another creative field, but I read my way into design. Reading Du Bois, Lefebvre, de Certeau, and bell hooks, I just became fascinated with the spatial dimensions of this social world they’re so interested in. So, from sociology, I went to city planning, and more and more inched my way into landscape architecture.

What I take away from sociology is the methods question. I think there’s something productive about that for designers. I believe we need to have a discourse on methods that we’re testing and evolving if we’re going to engage with major issues beyond the silo of our discipline. It is a question of balance. How do we keep design and research as a culture and tradition that’s productive for us but, at the same time, are able to ask other people to hold us accountable? That’s something that I bring from sociology into my work as a landscape architect.

KH Given that, what does an ideal practice look like to you?

SZ I think research and exploratory work integrated into the process of building landscapes is important in an ideal practice, but finding the appropriate financial mechanisms to support this in private practice is something we’re testing right now in my office.

We really push in the scope for a heavy front-end that is engaged politically and with community members. And, if I find myself in a room with elected officials or civic leaders or philanthropists, I try to make the case for creating funding opportunities for designers to get involved in work that happens before an RFP: the shaping of an RFP, the shaping of its scope, the strategizing around investment.

That’s what we learned at the GSD. Landscape architecture at the GSD is taught in a multi-scalar fashion, and often the students are positioned to identify their site and their project, which are the skills you need to be an advocate. Advocacy is embedded in the scales that we’re working in the Landscape Architecture department at the GSD. And we sort of accept that this mode of working and thinking ends when you leave the GSD, but I would like to see expanded formats for us to employ those methods and tools in the real world.

KH Olmsted wasn’t a passive participant in his time as a young journalist. Through this document, he was actively advocating for the abolition of slavery and rushing to complete and publish it in time to shape the minds of a very divided country on the brink of civil war. In a contentious context and on a charged topic, he builds his argument in opposition from an economic point of view. What do you think of this choice?

SZ It’s funny. This is often a conversation of fierce debate in the class. Is Olmsted’s voice adaptive? He writes about slavery with a very matter-of-fact tone about issues and observations that are anything but. Speaking personally on my own behalf, I feel that this can be productive when working in highly charged contexts. In my practice, we work on a lot of sites with contested narratives—very charged sites. I often find that it is productive to keep things matter-of-fact, just to keep projects moving and going, and not to repel anyone who might actually gain some knowledge from listening to the conversation. You have to be strategic about when you use a different tone and when it might be effective.

Negro Population of the United States Compared With the Total Population of Other Countries.

Olmsted talks about this in his personal letters—that he does want to have slave owners in the South as an audience. He wants to convince them. He wants to challenge their logic about slavery. He does aspire to that. As the years go on he became less convinced that it’s even possible, and then comes to the conclusion when he rewrites for

The Cotton Kingdom, “Subjugation is the only way we can bring the South into giving in with the North and rid them of slavery.” Basically, war is the only way that this is going to get solved. He’s just like, “There’s no talking to these people.”

But that was his intention initially with his tone, and he was explicit about that. I think that there’s something there, especially if you live a life within the implications of this history every day. Then there is a kind of matter-of-factness to these topics that you have to rely on in order to just live your life every day. Being overtaken emotionally by this is somewhat of a privilege, because you can do that and then go back to your regular life. But if you’re thinking about it every day, and you don’t have a choice about that, that’s where matter-of-factness is less disturbing, because it’s life. It’s everyday life. It is your life.

KH Because urban planners, architects, and landscape architects are working in public spaces, the work has an inherently political element. As you said earlier, you really wield a power in the ability to shape land. So, I am curious about how you view politics and design.

If we don’t silo Olmsted-as-a-political-writer from Olmsted-as-a-designer, then there is something exciting in seeing someone successfully synthesize politics and design into one—research and practice into one. Your practice is also managing to synthesize social research and design in ways that are exciting to see, given how many students and young professionals struggle to do both well.

When it comes to effectively engaging social issues, are there some things that you achieve as a politically engaged citizen that you can’t through design?

SZ One thing that we aim to do in my office is synthesize our social and cultural analyses with detail and construction. Those larger understandings of work can and should influence a landscape’s material expression. The built landscape is ultimately what makes people feel like they belong. In this way, a garden is just as political as a large-scale, regional infrastructure project.

What is it that was built and how does it feel to be in it? Is it acknowledging and supportive of my well-being or is it not? Does it feel reflective of my identity or not?

And so I hope that the suggestion here about understanding the macro is not the conclusion reached. I think the actual building of things at any scale is important, and given Olmsted’s level of detailed involvement in writing as well as building landscapes, I would say he shares that.

So, I would say they are separate, but I don’t think of a citizen and designer as entirely different. I guess I haven’t really thought of that distinction. Part of this is due to the fact that there are only 12 or 13 licensed Black women in landscape architecture in America.

KH Wow.

SZ Isn’t that crazy? It’s insane.

And so just being a landscape architect in my case is often politicized by people. They project things onto me. I often don’t have the luxury of separating the two. I’m always asked, “How did your experiences in life influence your landscape?” People project that, and so that separation is not afforded to me.

In reality, probably nobody can separate the two, but other people are never or rarely asked to articulate the connection between who they are and what they do. Have you ever heard somebody on a panel or a lecture say, “How has being a white male influenced the way in which you work as a designer?” Nobody ever asks that. And I always, every single day, get that question.

Land Owned by Negroes in Georgia, U.S.A. 1870–1890.

I think reflecting on the inextricable nature between who you are as a person, as a citizen, and how you work as a designer should be reflected on by everyone, not just people of color or women.

KH Designers are working in a particularly entangled reality. With the entirety of Olmsted’s career in view, what lessons of what to do and what not to do might we learn?

SZ Well, Olmsted was 31 when he went on this journey, which is the same age as a lot of people at the GSD.

KH That’s a great point.

SZ There’s a boldness to what he does. He is a very confident person. There is a boldness and an ability to envision his role and his impact in the world at a young age that is something to admire. And I think for me as Black woman, born and raised in the South, I had to do some of that too: envisioning things that don’t really exist in order to be where I am at, to have an office, to be on the faculty at a school like the GSD; these are things that I did not see. I didn’t even know landscape architecture existed until, frankly, relatively recently.

It’s kind of crazy, but I guess dreaming big and doing what you profess is a lesson we can all take away from his career in view. In his personal letters as early as age 22, he would often write to friends about his ambitions: “I don’t know what I’m going to do with my life, but I do know that I want to do big things. There are a lot of really big issues in the country, and I have this knowledge of the land and agriculture, but I’m also interested in politics.” And he’s just like, “What is this thing? How do I do this? How do I bring these things together? I want to make an impact.” And that’s the energy that our profession was founded on.

KH It’s a beautiful idea. And it never gets old to find these writings of almost mythological figures when they were young and they’re just like, “I have no idea what I’m doing.” [

laughs] It is always a relief.

SZ [laughs] Yes . . . Ah, I feel like Fred and I are old friends.

Pairs

is co-founded by Kimberley Huggins (MLA I ’20), Nicolás Delgado Alcega (MArch II ’20), and Vladimir Gintoff (MArch I ’21, MUP ’21), and supported by Dean Sarah M. Whiting and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Stephen Gray talks “Shaping Equitable Cities” in Harvard magazine cover story

Stephen Gray talks “Shaping Equitable Cities” in Harvard magazine cover story

Back in his hometown: Stephen Gray in downtown Cincinnati. Photo: Aaron Conway/aaconn studio. Courtesy of Harvard magazine.

Associate Professor of Urban Design (and GSD alumnus)

Stephen Gray defines his design philosophy in

Harvard magazine’s March 2021 cover story, “Shaping Equitable Cities.” By revealing moments that stoked and influenced his approach to urban design—some while a GSD student, some as a GSD professor, and many in between—Gray illustrates his vision for integrating equity into core design decisions, especially those shaping the public realm. He also discusses ongoing work and dialogue underway at his Boston-based Grayscale Collaborative, including projects in Boston’s evolving Seaport District.

As writer Jacob Sweet observes, many design firms demonstrate—or aspire to demonstrate—a signature look or style, while Grayscale Collaborative aims instead toward “establishing a signature

process.” As Gray explains, that process means incorporating everyday residents and community leaders into discussions of a project or a design from inception. More specifically, Gray discusses the need to consider questions of equity, racial justice, outcomes, and community when budgets and fundamental parameters of a project are still being decided. “That’s really where the center of power is,” he says. “Once a project is funded. . . you’ve already made it exclusive.” Gray amplifies that philosophy: “The pre-distribution of power means finding and identifying points of a process where power is exercised and decisions are made,” he says, “and making sure that people are involved centrally at that point.”

It’s a principle that lay at the heart of Gray’s GSD thesis: the study of a streetcar project in downtown Cincinnati—his hometown—that had been approved after multiple ballot efforts. Through his thesis study (advised by then-professors of urban planning Susan Fainstein and Richard Sommer), Gray realized the need for a so-called “urban growth regime.” He saw that public investment had to enrich the local community as much as it enriched businesses and developers.

Years later, Cincinnati was implementing its mixed-use downtown Innovation Corridor development, and Gray was among the Sasaki Associates urban designers working on the project. He got the chance to experience his design philosophy at work: after various economic analyses, presentations, listening sessions, and public conversations, Gray and his colleagues saw community organizations switch from opposing to supporting the project. The trust- and relationship-building mechanisms that Gray had centered in the design process would later help advance two other city initiatives, too.

“By the end of the project, not only did we have consensus,” Gray says, “but also all of the community-based organizations wrote letters of support to the Cincinnati Planning Commission.”

Read Harvard magazine’s March 2021 cover story, “Shaping Equitable Cities.” Womxn in Design celebrates International Womxn’s Day with a week of GRASSROOTS-themed events

Womxn in Design celebrates International Womxn’s Day with a week of GRASSROOTS-themed events

The Harvard Graduate School of Design’s

Womxn in Design (WiD) is honoring International Womxn’s Day 2021—Monday, March 8—with International Womxn’s Week (IWW), a

full week of programming involving students, faculty, alumnae, guest speakers, and social justice organizations, under the shared theme of GRASSROOTS. This year’s theme was, fittingly, brought to life during a “village meeting”—a bi-monthly gathering open to the GSD community, in which members, participants, and visitors alike contribute words of importance to them, with “grassroots” emerging as a unifying interest.

“There is a larger conversation we have in academia around what the role of design is in addressing systemic issues of injustice, and yet, I don’t think we ask ourselves enough about what our roles as community members are—as collaborators or facilitators in the process of shaping space—beyond our institutions,” says WiD Co-Chair Brittany Giunchigliani (MLA I ’21). “This week of events addresses the need to breakdown perceived barriers between academic work and grassroots organizing, while also advocating for building intimacy and care among each other.”

The series kicks off on Monday March 8 at 8:00 p.m. ET with a workshop led by the

Design As Protest (DAP) Collective exploring the intersectional roots of International Womxn’s Day. DAP members will also guide participants through the

Anti-Racist Design Justice Index, which provides a framework for tracking accountability and guiding concrete actions. This event is open to current faculty and students.

The IWW Keynote Address takes place the following evening when

Ananya Roy, professor of urban planning, social welfare, and geography at the University of California, Los Angeles and founding director of the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy, presents “

Undoing Property: Feminist Struggle in the Time of Abolition.” The event is free and open to the public, and

registration is required.

Other events include the symposium “Parity Talk: What’s Good?,” a collaboration with ETHZ + EPFL + TU Munich + TU Wien; a negotiation workshop led by Ming Thompson of Atelier Cho Thompson; an informal lunch and lecture with Catherine Seavitt Nordenson; and an event on advocacy within the field of design co-organized with the GSD’s African American Student Union, AfricaGSD, and Notes on Credibility, and featuring Diane Jones Allen,

Toni L. Griffin, Azzura Cox, and Pascale Sablan.

Throughout the week, those local to Cambridge can view the exhibition

GRASSROOTS on Gund Hall’s Cambridge Street and Quincy Street facades. The projection will be screened nightly from 4:00 PM – 11:00 p.m., beginning March 7 and ending March 14, 2021.

Still from the GRASSROOTS projection.

Despite the challenges of virtual programming, WiD saw this as an opportunity to engage with a greater variety of speakers and reach more poeple than in years prior. “IWW 2020 included some of the last in-person programs we at the GSD attended before the school closed,” says WiD Co-Chair Shira Grosman (MLA I AP/ MDes ULE ’21). “So this year, IWW feels both bittersweet and a wonderful opportunity to expand what and who IWW encompasses. With the theme of GRASSROOTS, we were empowered to reach beyond the GSD and partner with organizations like Design as Protest Collective as well as international institutions to build a broad, intersectional and collaborative network.” Co-Chair Junainah Ahmed (MArch I ’23) agrees: “Through intersectional discourse we can begin to deconstruct current paradigms of oppression in academia.”

The full program and links to register for individual events can be found on

WiD’s website. You can also follow programs as they unfold by visiting

@womxnindesign on Instagram.

Excerpt: The Incidents: Inhabiting the Negative Space by Jenny Odell

Excerpt: The Incidents: Inhabiting the Negative Space by Jenny Odell

Three time zones and three thousand miles away, artist and writer

Jenny Odell was invited to be the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s 2020 Class Day speaker in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. In her forward to

Inhabiting the Negative Space, which presents Odell’s speech in print as the ninth title in

The Incidents book series, Dean

Sarah M. Whiting notes that Odell brought “a combination of frankness and optimism that made each of us feel like we were in conversation with someone who knew every one of us individually.” Within the text, Jenny states that she herself finished her undergraduate studies in 2008— straight into a recession. Ten years following her graduation, she wrote the book

How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, rethinking the meaning of productivity and observing individual and collective attention and will.

By Jenny Odell

I believe that we individually have the ability to direct our attention—for example, to see in multiple time frames at once, or at the very least outside of the default temporality of everyday life. But I also believe that we need help doing this, and that’s why the role of the artist and designer that’s most important to me right now is indeed one as an orchestrator of attention, someone who can create the lenses with which we can see a completely different reality—not one that is imaginary or fabricated, but that has in fact been there all along. ——— Of course, doing this requires close attention on the orchestrator’s part as well, which is what brings me to the second idea I mentioned, of design as response—not to the world as you want it to be or expect it to be, but a response to the world as it really is, right now, in all of the detail that unfolds if you just give yourself time to see it.

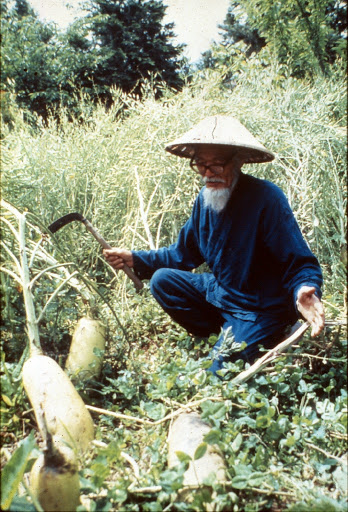

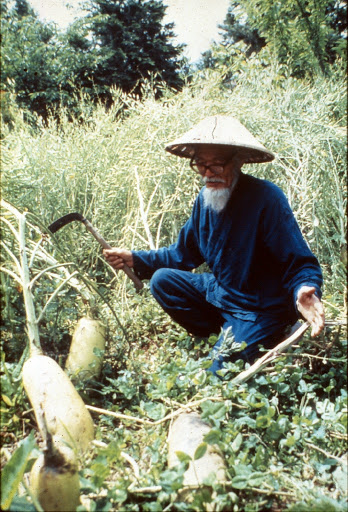

Masanobu Fukuoka, (1913-2008). Photo: Larry Korn.

One of my favorite practitioners of this mindset is the Japanese farmer Masanobu Fukuoka. Fukuoka is known for perfecting a system in the 1970s that he later called “do-nothing farming.” Flouting the established protocols for traditional rice farming, he devised a way of farming that used far fewer inputs and less labor. Instead of flooding fields and sowing rice in the spring, he scattered seeds directly on the ground in the fall as they would have fallen naturally. In place of conventional fertilizer, he grew a cover of green clover and threw the leftover stalks back on top when he was done. ——— In the end, Fukuoka’s farm was more productive than neighboring farms, and it also rehabilitated the soil instead of depleting it, as so many farms do over time. The system was even capable of creating farmable soil on inhospitable strips of land. ——— What I want to stress here is time. It took Fukuoka decades of observation and failed experiments to arrive at this system. Rather than imposing an abstract will on a compliant piece of land, what he was doing was more akin to patient collaboration. As you can imagine, for someone who finally figured out how to do more by doing less, Fukuoka had a great sense of humor. In his book The One-Straw Revolution, he wrote,

“Because the world is moving with such furious energy in the opposite direction, it may appear that I have fallen behind the times,” and, “That which was viewed as primitive and backward is now unexpectedly seen to be far ahead of modern science. This may seem strange at first but I do not find it strange at all.”

Cover image: The One Straw Revolution by Masanobu Fukuoka.

In that book, Fukuoka talks about an experience he had as a young man, when he was studying plant pathology under a brilliant researcher. Fukuoka essentially overworked himself to the point of hospitalization, and when he was discharged he wandered to a hill overlooking the local harbor and fell asleep underneath a tree. When he woke up in the early morning, he was shocked into awareness by the flight of a night heron—incidentally one of my favorite birds. He wrote,

“Everything I had held in firm conviction, everything upon which I had ordinarily relied was swept away with the wind. I felt that I understood just one thing. Without my thinking about them, words came from my mouth: ‘In this world there is nothing at all. . . .’ I felt that I understood nothing.”

It’s easy to read despair into that phrase—“understood nothing”—but what Fukuoka is describing is a moment of exhilaration, and the underpinnings of the humility that eventually led to do-nothing farming. To understand nothing is to see everything—to have an empty enough mind to observe what is actually there. After all, it was humility with respect to the land and its inhabitants that allowed Fukuoka to design a successful system, one that made use of and did justice to the already-present intelligence in the ecosystem. To come back to Pauline Oliveros, you could say that he was practicing a form

of deep listening.

The Incidents is a book series based on events at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Learn how to purchase Inhabiting the Negative Space

, copublished by the Harvard University Graduate School of Design and Sternberg Press, Spring 2021. GSD exhibitions turn “Inside Out”

GSD exhibitions turn “Inside Out”

This spring, Harvard Graduate School of Design has turned its Druker Design Gallery, Experiments Wall, and other exhibition spaces “Inside Out,” with installations shown through a series of exterior projections on the building’s facade. The series, entitled “Inside Out,” will be screened nightly (4:00 pm to 11:00 pm, EST) through March 18, rotating through a weekly roster of shows that exhibit some recent preoccupations among Harvard GSD faculty and students, selected and curated from among an open call last November.

From March 1 through March 7, “Inside Out”

presents four films highlighting student work from

Farshid Moussavi‘s Fall 2020 GSD

option studio, “Dual-Use: The function of a 21st century urban residential block.” The studio concerned itself with the politics latent within architecture, carried out through making aesthetic decisions regarding everyday spaces, and the resultant, and profound, consequences on people’s lives. In particular, the studio explored the subject of housing combined with working from home.

Projects currently on view in “Inside Out,” drawn from Farshid Moussavi’s Fall 2020 option studio “Dual-use: The function of a 21st century urban residential block.” Clockwise from top left: “Mutating Threshold” by Dan Lu, “Dual-Use Vertical Village” by Qin Ye Chen, “Dual-Use” by Erik Fichter, “Thrive – An Ethos of Collaboration and Support” by Devashree Shah

“Inside Out” premiered in early February with a pair of three-minute projections, or “filmic studies,” produced by GSD professor

Helen Han, and concludes on March 19 with a look at student work from the Department of Landscape Architecture. Han’s “

Scalar Shifts: Two recent filmic studies of Jewel Changi Airport and The Clark Art Institute” proceeded through the layers and sequencing of vegetation, light, and other natural phenomena at Williamstown’s Clark Art Institute grounds; its companion video, “Garden of Wonder,” offered a tour of Singapore’s Jewel Changi Airport and the public space within, filmed over four days in November 2019 in collaboration with Safdie Architects. “Inside Out” proceeded with student-directed projection “

Floating Between Borders” (February 15-21), presenting a futuristic, imagined look at what the world could look like without formal national boundaries—an inherent “critique of the bureaucracy of geopolitical borders,” the students write, imagining what the world could look like if people could move freely among nations.

Following the exhibition of Moussavi’s “Dual-use” studio, “Inside Out” will feature a video celebration of Womxn in Design (March 8-14); a view of select thesis projects (March 15-21) and core-studio and option-studio work (March 25-31) from the Department of Architecture; and a look at the Department of Landscape Architecture’s recent pedagogical tools (April 1-7), including 3D-printed maps, toolkits, and other physical ephemera that students have received at home this academic year.

“Inside Out” follows last fall’s “2020 Election Day at Gund Hall”

presentation. Gund Hall is a perennial voting location, and this show called all residents of Cambridge’s Ward-Precinct 7-3 to vote in the November 3, 2020 election, and doubled as a wayfinding device that instructed voters where they should enter and exit the building.

To learn more about the GSD’s past and present exhibitions, visit the Exhibitions

webpage.

Built in 1901, the harbor-front Teweles and Brandeis Grain Elevator was decommissioned in 1960 and sat idle for the next 50 years. When it was facing demolition in 2018, a campaign to save the structure led to the involvement of LA DALLMAN Architects and its engineering team. With strategic subtractions and additions to the utilitarian structure, their adaptive reuse design reimagines the site as a new performance space and tourist destination.

Built in 1901, the harbor-front Teweles and Brandeis Grain Elevator was decommissioned in 1960 and sat idle for the next 50 years. When it was facing demolition in 2018, a campaign to save the structure led to the involvement of LA DALLMAN Architects and its engineering team. With strategic subtractions and additions to the utilitarian structure, their adaptive reuse design reimagines the site as a new performance space and tourist destination.

Pairs is a student-led journal at the Harvard Graduate School of Design dedicated to conversations about design that are down to earth and unguarded. Each issue is conceptualized by an editorial team that proposes guests and objects to be in dialogue with one another. The following is an excerpt of a conversation from Issue 01 between Pairs co-founder Kimberley Huggins (MLA I ’20) and Sara Zewde, Assistant Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, titled “On the Foundational Spirit: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits.”

KIMBERLEY HUGGINS So, “Cotton Kingdom, Now”: your return to and inaugural class at the GSD!

Your class is occurring during a time when the dominant narratives of history and their intended values are being seriously questioned. In the context of the education of landscape architecture, this sentiment often materializes in the student body as a desire to toss the canonical history and start anew. Students struggle to see how it is equipping them in the face of contemporary social and environmental realities. Subsequently, there is a desire to excise it. It is not uncommon to hear students say, “I do not want to hear about Olmsted anymore. I do not want to talk about gardens anymore.”

And so while many are asking for the focus to be moved from Frederick Law Olmsted with a belief that the more relevant lessons are elsewhere, what was it that drew you in further to focus on his time as a young journalist?

SARA ZEWDE The landscape architecture that is taught at the GSD now is significantly different than the landscape architecture I learned when I started in 2011. Even a comparison after a few years is mind-boggling. Things are rapidly changing and it is not like that change started in 2011. When I speak with students who studied before me, it becomes clear that there have been a number of significant shifts within the last 15 years in landscape architecture education.

I don’t think there was a single Black person referenced in my three years of landscape architecture education. Be it in a syllabus, a chance to read their writing, to learn about their thoughts on the world, or to study their projects as precedent. On the other hand, there were many slave holders celebrated. Thomas Jefferson was presented unproblematically for his brilliant innovations in landscape design. And so I was perpetually, in those three years, very lost about my place in this profession. In fact, I took a year off and went to work for Walter Hood and came back having more confidence in my ability to see myself in this profession and understanding about how my experience in the world can influence design. Because, otherwise, when I would ask certain questions in school, it was often met with, “You’re in landscape architecture; why would you bring that up?”

In my third year, we had a guest lecturer in our “Professional Practice” class who, in passing, mentioned that Olmsted visited the South. That was the first I had ever heard of that. We had already learned a lot about Olmsted, but I had never heard that he traveled through the South to write about the conditions of slavery. I followed up with the guest lecturer, and with my two professors—I still have this email. I often revisit that email chain because it has led me to this point in my research. I asked for further reading material about Olmsted’s travels and they sent me a reference, but what I really wanted was to be able to reflect on the connection between his abolitionist thoughts and his practice of landscape architecture.

Pairs is a student-led journal at the Harvard Graduate School of Design dedicated to conversations about design that are down to earth and unguarded. Each issue is conceptualized by an editorial team that proposes guests and objects to be in dialogue with one another. The following is an excerpt of a conversation from Issue 01 between Pairs co-founder Kimberley Huggins (MLA I ’20) and Sara Zewde, Assistant Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, titled “On the Foundational Spirit: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits.”

KIMBERLEY HUGGINS So, “Cotton Kingdom, Now”: your return to and inaugural class at the GSD!

Your class is occurring during a time when the dominant narratives of history and their intended values are being seriously questioned. In the context of the education of landscape architecture, this sentiment often materializes in the student body as a desire to toss the canonical history and start anew. Students struggle to see how it is equipping them in the face of contemporary social and environmental realities. Subsequently, there is a desire to excise it. It is not uncommon to hear students say, “I do not want to hear about Olmsted anymore. I do not want to talk about gardens anymore.”

And so while many are asking for the focus to be moved from Frederick Law Olmsted with a belief that the more relevant lessons are elsewhere, what was it that drew you in further to focus on his time as a young journalist?

SARA ZEWDE The landscape architecture that is taught at the GSD now is significantly different than the landscape architecture I learned when I started in 2011. Even a comparison after a few years is mind-boggling. Things are rapidly changing and it is not like that change started in 2011. When I speak with students who studied before me, it becomes clear that there have been a number of significant shifts within the last 15 years in landscape architecture education.

I don’t think there was a single Black person referenced in my three years of landscape architecture education. Be it in a syllabus, a chance to read their writing, to learn about their thoughts on the world, or to study their projects as precedent. On the other hand, there were many slave holders celebrated. Thomas Jefferson was presented unproblematically for his brilliant innovations in landscape design. And so I was perpetually, in those three years, very lost about my place in this profession. In fact, I took a year off and went to work for Walter Hood and came back having more confidence in my ability to see myself in this profession and understanding about how my experience in the world can influence design. Because, otherwise, when I would ask certain questions in school, it was often met with, “You’re in landscape architecture; why would you bring that up?”

In my third year, we had a guest lecturer in our “Professional Practice” class who, in passing, mentioned that Olmsted visited the South. That was the first I had ever heard of that. We had already learned a lot about Olmsted, but I had never heard that he traveled through the South to write about the conditions of slavery. I followed up with the guest lecturer, and with my two professors—I still have this email. I often revisit that email chain because it has led me to this point in my research. I asked for further reading material about Olmsted’s travels and they sent me a reference, but what I really wanted was to be able to reflect on the connection between his abolitionist thoughts and his practice of landscape architecture.