Walter Hood appointed Spring 2021 Senior Loeb Scholar

Walter Hood appointed Spring 2021 Senior Loeb Scholar

Walter Hood has been appointed the Harvard GSD

Loeb Fellowship‘s Spring 2021 Senior Loeb Scholar, a cherished and dynamic role within the GSD community. The heart of the Senior Loeb Scholar program is a week in residency at the GSD in which the Scholar presents a public lecture, workshops, and other engagements. The Senior Loeb Scholar program has offered the GSD community opportunities to learn from and engage with visionary designers, scholars, and thought leaders in a uniquely focused context.

Hood will join the GSD for the traditional Senior Loeb Scholar week “in residence” (virtually) next February 22 through 26, 2021. Details on Hood’s residency engagements will be shared in the coming weeks.

Hood is the David K. Woo Chair and Professor of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning at the University of California, Berkeley, and was recently the Spring 2020 Diana Balmori Visiting Professor at the Yale School of Architecture. He also is Creative Director and Founder of the Oakland-based

Hood Design Studio, which he established in 1992.

Over his career, Hood has reworked sites like traffic islands, vacant lots, and freeway underpasses into dynamic spaces that challenge the legacy of neglect of urban neighborhoods. Through engagement with community members, he teases out the natural and social histories as well as current residents’ shared patterns and practices of use and aspirations for a place. Most recently, his landscape design concept for the

International African American Museum drew inspiration from the cultural significance of the museum’s story and the local landscape of the Carolina lowcountry, taking cues, as his studio writes, from the tradition of “hush harbors”—landscapes where enslaved Africans would gather often in secret, outside the view of slave owners, to freely assemble, share stories, and keep traditions from their homeland alive.

Hood recently co-edited

Black Landscapes Matter (2020, University of Virginia Press) alongside Grace Mitchell Tada. His Senior Loeb Scholar appointment follows a series of recent honors: he is a recipient of the 2017 Academy of Arts and Letters Architecture Award, 2019 Knight Foundation Public Spaces Fellowship, and 2019 MacArthur Fellowship. And just this month, Walter Hood Studio made its debut on the esteemed AD100 list.

Hood joins a cohort of previous Senior Loeb Scholars, who include Bruno Latour (2018-2019); Kenneth Frampton and Silvia Kolbowski (2017-2018); Richard and Ruth Rogers (2016-2017); and David Harvey (2015-2016).

Learn more about the Loeb Fellowship via the Loeb Fellowship

website.

How Not to Write About Design: A guide for anyone looking to move beyond form, space, order, and structure

How Not to Write About Design: A guide for anyone looking to move beyond form, space, order, and structure

Architects are often reluctant writers, choosing instead to express themselves in other ways. Perhaps this is because architectural education strongly emphasizes graphic over verbal communication, or because the proliferation of overly complex prose in architectural theory engenders distaste for writing among architects. There are many reasons, but one convincing argument is that it is the result of intentional neglect—a symptom of modernist thinking in architecture.

Adrian Forty argues, in Words and Buildings, that modernism developed a deep suspicion, even a “horror of language,” in all of the visual arts. “The general expectation of modernism that each art demonstrate its uniqueness through its own medium, and its own medium alone,” he says, “ruled out resort to language.” In other words, modernists insisted that their work should speak for itself. Modernism therefore developed a very limited vocabulary (Forty lists “form,” “space,” “design,” “order,” and “structure” as its key words) and a distinctive “new way of talking about architecture” that was extremely taciturn. It made the difficult task of writing almost superfluous for architects, and they simply chose not to do it.

The general expectation of modernism that each art demonstrate its uniqueness through its own medium, and its own medium alone, ruled out resort to language.

Adrian Fortyon modernism’s “horror of language”

Clearly, though, written language is essential for architects. Architectural drawings do not speak for themselves: any set of drawings is full of essential labels, descriptions, explanations, and disclaimers. And in professional practice, Forty emphasizes, “Language is vital to architects—their success in gaining commissions, and achieving the realization of projects frequently depends upon verbal presentation and persuasiveness.” Much of this happens orally, but client communication, project documentation, press releases, and advertising copy are all routine, indispensable forms of writing in architecture.

What might not be vital to architecture, however, is a specifically “architectural” language, vocabulary, or writing style. In a 2013

Arch Daily article, “Why Good Architectural Writing Doesn’t Exist (And, Frankly, Needn’t),” writer Guy Horton asks, “If writing about architecture is to serve the profession on some level, wouldn’t it be best if it reached out to the popular imagination, beyond the confines of institutionalized insularity where architects and ‘architectural writers’ merely talk amongst themselves?” So, he proposes, “Let us posit that there should be no architectural writing, but merely writing that happens to be about architecture.” This might eliminate the jargon and excess complexity that plague architectural writing. It might also embolden architects’ thinking. Sociologist Howard Becker claims that in his own discipline, excess verbiage is a symptom of uncertainty: “writers routinely use meaningless expressions to cover up” weak claims, and timid thinking leads almost inevitably to bad writing.

Reluctance to take on the task of writing, suspicion of the communicative potential of language in the arts, and unease with making bold assertions about design all intensify the difficulties of writing about and for architecture. This is especially acute for students in design courses, where writing is rarely a priority. Faculty in three GSD courses in spring 2020 challenged this model, pushing students to face the task of writing boldly.

Mack Scogin, Merrill Elam, and Helen Han’s studio, “King Tut’s Skull,” George Legendre’s “Digital Media: Writing Form,” and

Pier Paolo Tamburelli and Thomas Kelley’s seminar, “Book Project Number Zero,” each encouraged students to consider writing from a starkly different perspective, but they all started with the assumption that writing plays an essential role in architecture.

At the first meeting of “King Tut’s Skull,” students were asked to recall and describe their first spatial memory. Scogin marvels at the results of this simple assignment: “It’s really remarkable what comes out of that writing exercise—the memory and how it’s constantly visited and revisited. . . it’s probably one of the most defining elements in the course.” The extended exercise works two ways: the students build a clear, sophisticated vision around a vague impression, and the faculty establish mutual trust with the students. They “develop a belief in us,” Scogin says, “and we’re really serious about trying to understand them as individuals.”

The writing is so remarkable, Han notes, because the students “know that it’s not like ‘Oh, make a form of a building or anything like that.’ It relieves that pressure.” The writing is not “architectural,” in other words. “And so then,” Han says, “they just [write] what they instinctively want to write or how they want to write.” Through the process, the students use writing to understand their own thinking. It becomes, Han explains, “an initial very intuitive way for them to expose themselves in terms of both their interest, but also how they see things.”

[Writing] opens their mind up . . . . It’s a way for [students] to discover their own architecture.

Mack Scoginon the design exercise of writing

The writing “opens their mind up . . . . It’s a way for them to discover their own architecture,” Scogin says. However, when they must produce more discipline-specific writing later in the studio—a design thesis statement—the students struggle. “It becomes a hurdle,” Scogin explains, “and they freeze up a bit because all of a sudden: Oh! You’re talking about architecture.” And the challenge for the faculty is to remind them of their fluency. “We just keep putting it back in front of them,” Scogin says, and Han laughs, “Yeah, we keep telling them to write it again, write it again . . . .” Writing about “architecture” was hard until it became, instead, writing about what they know, which is more natural, more powerful.

If “King Tut’s Skull” demonstrated that fluency with one kind of writing can help with other modes of expression, “Digital Media: Writing Form” amplified that notion, challenging students to understand architecture by using deeply unfamiliar idioms. They put themselves “in the mindset of the software designer, looking under the hood” of software, Legendre explains. Their task, he says, is more like “writing things” than sketching or modeling them, and they have many ways to do this. The course used calligraphy, haiku, statements in simple mathematical terms, and other modes of writing. Legendre compares the students’ effort to the

Exercises in Style, by Raymond Queneau, “where a meaningless incident is retold 100 ways, using a completely different idiom, and the only idea is to help you focus on the variation.” The course therefore approached “computation as a problem of comparative literature.”

Legendre asked students to position their writing somewhere between machine language (“which is gibberish to us,” he says) and the user interface of “buttons and sliders” (“which enable us to do whatever we want”). In this unfamiliar place, “the struggle with the opacity of instruments is somehow bringing back the question of literacy,” Legendre says. The students used a language in which they could invent things, where they could get at “the essence of what we are trying to do” in design. They reached this position gradually, first becoming attentive to how architects read space, and moving “through the process of understanding how to write space in all three dimensions.” They struggled in this territory between incomprehension and free expression to learn again how to use writing to say important things in architecture.

Architects read space, and moving ‘through the process of understanding how to write space in all three dimensions.’

Legendre noting studio observations on the comprehension and expression of architectural space

Meanwhile, in “Book Project Number Zero,” students focused on a largely unwritten, imaginary text to develop a richer understanding of architectural design. The seminar began from the assumption that “architecture is inseparable from bookmaking,” that “books are the main instrument of architectural propaganda.” And, despite the challenges they might face as writers, “It’s quite important for an architect to write,” Tamburelli explains, because “it makes his or her architecture better—more conscious, more intellectually sophisticated.”

Students wrote a short introduction and an index for a book they envisioned (themes varied broadly, from ideas about the personhood of rivers to the lamentable state of architecture in China). However, the main concern of the course was not the writing—it was the book itself, as a designed object, an object “with weight,” Kelley says, “stronger” in some ways than a building. Through the process, the students came to understand the book as “a sort of a tool to actually make architecture,” Tamburelli observes, as well as a tool of self-reflection.

Whether architects are bad or excellent writers is immaterial to the understanding that emerged in each of these courses: that a “horror of language” inherited from modernism is deeply misguided. Writing is an essential creative medium and a vital tool for making architecture.

Excerpt: A Democratic Infrastructure for Johannesburg, by Benjamin Bradlow

Excerpt: A Democratic Infrastructure for Johannesburg, by Benjamin Bradlow

“Five years ago, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s

Just City Lab published

The Just City Essays: 26 Visions of Inclusion, Equity and Opportunity. The questions it posed were deceptively simple: What would a just city look like? And what could be the strategies to get there? These questions were posed to mayors, architects, artists, philanthropists, educators and journalists in 22 cities, who told stories of global injustice and their dreams for reparative and restorative justice in the city.

These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at

designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays

A Democratic Infrastructure for Johannesburg

By Benjamin Bradlow

There are two main legacies that define urban inequality in South Africa: housing and transport. Apartheid was not only a racial ideology. It was also a spatial planning ideology.

Johannesburg’s development into a wealthy, white core of business and residential activity, with peripheral black dormitory townships, was a result of specific legislation and government action accountable only to white citizens. Black people were confined to houses in townships that had little economic value. Black townships were synonymous with urban poverty. These houses were far away from business activity and jobs. As population movement controls eroded in the late 1980s, informal settlements began to concentrate next to formal townships. The story of Johannesburg, the financial center of South Africa, can help understand how the struggle to build these connections defines the extent to which Johannesburg can be considered “just.”

Today, Johannesburg offers unique insights into the prospects for other cities in Africa. This is not because most cities in Africa are similar to or are likely to become similar to Johannesburg. But Johannesburg has a basic historical characteristic that resembles that of many African cities: it was planned for inequality. Johannesburg’s uniqueness also marks it as a lodestar for other African cities. It is a meeting point of migrants from all over the continent, and an economic engine of growth on the continent. These flows of people, money, and goods, in and out of the city, mean that the impact of the city is continental.

The notion of a just city in Africa will have to accommodate the extent to which the hopes of earlier generations of social scientists and policy-makers for rural-led development on the continent have now been rendered moot by economic patterns that are both global and local. In Johannesburg, one of the most industrialized cities on the African continent has become a magnet for rural South Africans, and international migrants from other African countries. The primary infrastructural challenge is not only about identifying technical shortcomings or mere numbers of delivery. It is about generating the voice from below to demand that infrastructure reach those who need it most, and to ensure the political will to manage contentious distributional decisions about land and public finances.

I want to show why this is so difficult, and how, in order to make the decisions that are “just,” we need to first make sense of the history that lies behind those decisions. Continue reading on designforthejustcity.org…

Toni Griffin discusses what Biden’s presidency could mean for America’s cities in Architectural Digest

Toni Griffin discusses what Biden’s presidency could mean for America’s cities in Architectural Digest

Professor in Practice of Urban Planning and founder of Urban American City

Toni L. Griffin was recently featured in

Architectural Digest as one of six experts considering what a Biden presidency could mean for the future of architecture and the built environment. Griffin highlights how the Biden administration will be “inheriting a series of challenges—like COVID and the epidemic of violence and brutality.” In response, says Griffin, “we can no longer continue to rebuild in the same way we always have. We have to take and learn from the failures of our infrastructures and begin to develop those in new ways now.”

Read Griffin’s full response in the article “

What Biden’s Presidency Could Mean for Architecture and the Built World.”

Urban Planning students win grand prize in affordable housing hackathon

Urban Planning students win grand prize in affordable housing hackathon

A team of Master in Urban Planning students consisting of Zoe Iacovino (MUP/MPP ’23), Ryan Johnson (MUP ’22), Chadwick Reed (MUP ’22), and Gianina Yumul (MUP ’22) has won the

2020 Ivory Innovations Hack-A-House competition’s grand prize in the Policy and Regulatory Reform category. The annual 24-hour hackathon-style charette is focused on finding tangible, economically viable solutions to the affordable housing crisis facing the United States. Teams are given a prompt related to housing affordability and have 24 hours to turn around a proposal. The event is co-sponsored by Harvard’s

Joint Center for Housing Studies.

“Hack-A-House is by design setup to engage, encourage and inspire the next generation of entrepreneurs, community builders and decisionmakers in identifying new and innovative solutions that make housing more affordable and attainable,” said Abby Ivory, director of Ivory Innovations, in a

press release announcing the 2020 winners. “The connection between housing, the pandemic and associated economic challenges made this already vexing issue that much more real to many participants. Our winners were able to demonstrate additive solutions for all three of these extremely difficult issues.”

The GSD team’s proposal, “

Parking Lot Potential,” aims to “convert excess parking to affordable manufactured housing in a post-COVID world.” Parking lots were identified as sources of vacant space, especially as companies shift to telework during the pandemic. They are also, the

team noted, more amendable to development than unused land, particularly when it comes to manufactured housing.

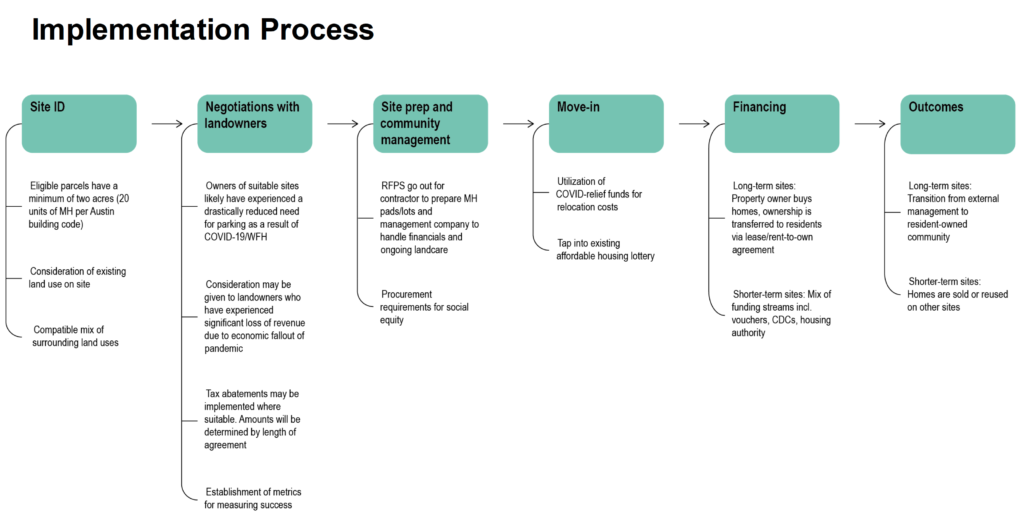

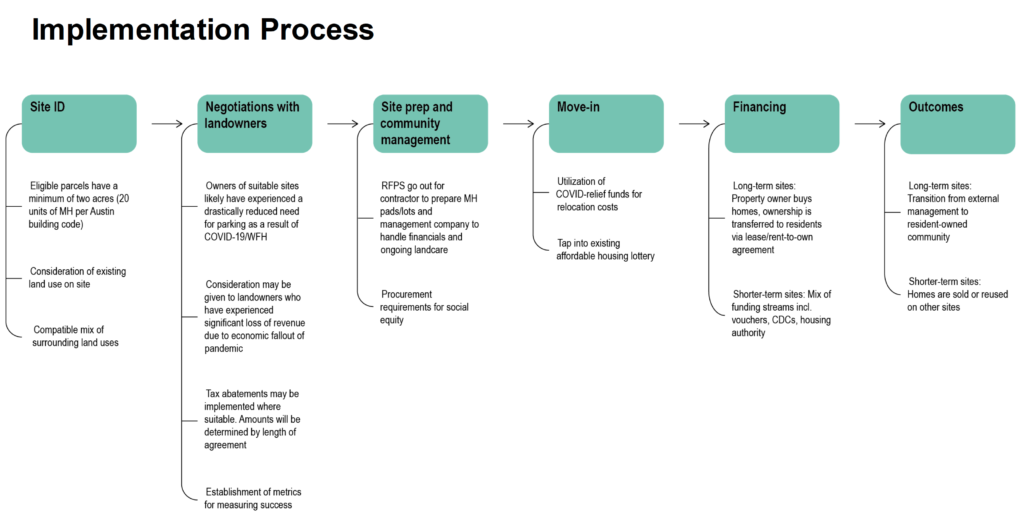

The essence of the project is an implementation tool kit, which outlines each step of the process, from site identification and negotiating with landowners, to community management, financing, and final outcomes. While the tool kit is designed for broad application, the team chose Dell headquarters in Austin, Texas—a city with a high rate of renters and ethnic diversity—as its test case. The site currently has an excess of 2,000 parking spaces, which translates to 12 acres available to be converted into a mobile home community.

The team found that the site’s proximity to grocery stores, transit, and infrastructure made it an ideal place for new housing and concluded that there were environmental and economic benefits for both renters and the existing site owners.

Watch the team’s

video presentation.

Landscape Architecture Magazine discusses “Dismantling the Design Syllabus” with GSD’s Sara Zewde, Anita Berrizbeitia

Landscape Architecture Magazine discusses “Dismantling the Design Syllabus” with GSD’s Sara Zewde, Anita Berrizbeitia

Amid a year of design introspection on issues of race, culture, identity, and equity,

Landscape Architecture Magazine’s November 2020 issue takes up “Dismantling the Design Syllabus,”

presenting faculty from various landscape architecture programs and their thoughts on what an anti-racist pedagogy looks like. The magazine spoke with, among others, Harvard Graduate School of Design’s

Sara Zewde (MLA ’15), Assistant Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture, and

Anita Berrizbeitia (MLA ’87), Professor of Landscape Architecture & Chair of the

Department of Landscape Architecture.

Upon her GSD faculty appointment this past summer, Zewde became the first tenure-track Black woman professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture (According to the magazine,

Zewde is one of 19 Black landscape architecture professors at accredited programs in the United States).

As reporter Zach Mortice writes, landscape architecture programs across the United States are confronting questions of race and social justice that have been deepened in the months following the May murder of George Floyd by police, and months of protests thereafter. With discussions and dialogue around structural racism shifting toward questions and reassessments of design curricula and reading lists—in landscape architecture programs and throughout design schools—Zewde tells the magazine, “I have never seen this kind of conversation around the actual curriculum, and that’s what excites me.”

In the feature, Berrizbeitia offers additional observations on ways the landscape architecture field can and should continue to evolve in light of recent cultural dialogue. Mortice observes that the field’s broad focus on ecological frameworks is evermore relevant, but that without equivalent focus and attention given to social considerations, including community, economics, and culture, landscape architecture can encourage gentrification and displacement.

“By focusing so much on ecological practices, [landscape architects have] put these ecological practices where the money is, rather than where the money is not,” Berrizbeitia says. “The field has not understood that ecology also has social content embedded in it.”

Following reconsideration of the landscape architecture curriculum this summer, Berrizbeitia committed the Department of Landscape Architecture to a close, introspective look at issues of race and justice, including the introduction of intra-departmental facilitated discussions on race and gender and a departmental diversity committee. Within the curriculum, faculty committed to re-centering disciplinary questions throughout core and elective courses by expanding precedents and situating projects within a broader set of discussions in order to more carefully interrogate and address these concerns and issues.

In this summer’s GSD series

Architecture, Design, Action, Berrizbeitia offered

further expansion on these plans.

“To demonstrate the relevance of the field, we often boast of the multivalence of landscape architecture, how it touches on all aspects of the natural and the social spheres,” she said. “Yet as often as we explain the many ways that landscape relates to everything, we neglect to explain what landscape hides behind its physical manifestation, its appearance. We do not as often discuss the histories, processes, and practices that have led to the present state of landscape, to the climate crisis in all its manifestations, to pandemics, and to social injustice and exclusionary public realms.”

Zewde is founding principal of Studio Zewde, a design firm practicing landscape architecture, urbanism, and public art. Her practice and research start from her contention that the discipline of landscape architecture is tightly bound by precedents and typologies rooted in specific traditions that must be challenged, and her projects exemplify how sensitivities to culture, ecology, and craft can serve as creative departures for expanding design traditions.

In 2014, while a GSD degree candidate, Zewde was named the annual National Olmsted Scholar by the Landscape Architecture Foundation, among other awards and honors. Returning to the GSD as a member of the faculty, she is currently leading the GSD option studio “

Cotton Kingdom, Now” and teaching in the landscape architecture core sequence.

Presently the chair of the GSD’s Department of Landscape Architecture, Berrizbeitia—who, like Zewde, earned her MLA from the GSD—focuses research on design theories of modern and contemporary landscape architecture, the productive aspects of landscapes, and Latin American cities and landscapes.

“Landscape architecture, landscape, land itself—this is where, simply put, life and all of its conflicts takes place,” Berrizbeitia said in the GSD’s

Architecture, Design, Action. “This means that, as long as the capitalist spatial mode prevails, landscape is always a contested ground.”

Excerpt: Justice from the Ground Up, by Julie Bargmann

Excerpt: Justice from the Ground Up, by Julie Bargmann

“Five years ago, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s

Just City Lab published

The Just City Essays: 26 Visions of Inclusion, Equity and Opportunity. The questions it posed were deceptively simple: What would a just city look like? And what could be the strategies to get there? These questions were posed to mayors, architects, artists, philanthropists, educators and journalists in 22 cities, who told stories of global injustice and their dreams for reparative and restorative justice in the city.

These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at

designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays

Justice from the Ground Up

By Julie Bargmann

Soil contamination is a baseline condition for most of the sites I’ve worked on over the past two decades. The toxic imprint derives from industry—steel production, shipbuilding, fabrication of automobile and machine parts, to name just a few—in both urban and rural settings. But it also comes from lead-containing gasoline and paint, banned long ago but still quietly wreaking havoc. It’s a byproduct of the human pursuit of greater material wealth and a more convenient and comfortable life. In other words, it’s the legacy of progress, for better or worse.

As a landscape designer with expertise in toxic remediation and the regeneration of fallow land, the “better or worse” part is vitally important to me. I can say that with certainty, thanks to hindsight and 30 years of academic and professional experience. I didn’t grow up with the term “environmental justice,” which came into use in the 1980s to describe, in part, the unequal distribution of the benefits and burdens of progress. But I now know what a growing body of research shows: in the United States there’s a disturbing overlap between the maps showing where poor people and ethnic minorities live, and where contaminated soils exist.

You might use a stronger word than “disturbing” if you or a loved one were to develop a learning disability, cancer, or liver damage, which are just three of the many proven ill-effects of poisoning by lead, arsenic, and other pernicious elements found in soil. As I write this essay, residents of Vernon, California, in East Los Angeles, a low-income and largely Latino community, were celebrating a bittersweet victory, after forcing the closure of a battery recycling plant owned by New Jersey–based Exide Technologies. The sickening part of the story, pun intended, is that the plant operated for two decades after its environmental violations were first reported to the California Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC). Both the cleanup efforts (just 150 of 10,000 contaminated properties were reported to have undergone soil remediation as of early October) and the official response have been weak. “All of us could have acted sooner to develop a more complete picture of what the operations of that facility meant to the health of the residents around it,” DTSC director Barbara A. Lee said. She hastened to add that “the department had tried to shut down the facility in the past but the courts blocked the effort,” according to one published report.

When I read that I chuckled sadly to myself. It reminded me of an exchange I had a few years ago with a high-ranking city official with oversight of a new development for low-income residents I was working on. The developers were eager to start construction, to show “progress,” so they broke ground before testing the soil. Sure enough, the dirt was hot. I had joined the project late, when the momentum to build the inaugural prototype house was unstoppable. But when I learned the test results, remediation was still possible, and regardless, I was bound to report them. I still get a pit in my stomach when I think of the official’s response, which went something like this: The city has enough problems that are plain to see, so let’s not add to them by disclosing a difficult truth, especially one that’s invisible. To my disappointment, the project team elected not to address the contamination, and I was politely excused from the job. Continue reading on designforthejustcity.org…

Bodies in Motion: Jennifer Newsom on foregrounding the kinetic body in architectural representation

Bodies in Motion: Jennifer Newsom on foregrounding the kinetic body in architectural representation

Can you depict a sweating body in an architectural drawing? Are lines capable of expressing the exhaustion felt when climbing a steep incline? And what is drawing’s capacity to represent the effects of powerlessness, fear, and objectification experienced by bodies that feel a space does not belong to them, as, for example, Black bodies too often do in America?

In her fall studio, “

Movements,”

Jennifer Newsom, design critic in architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, asks students to consider such questions which foreground the body—the kinetic body in particular—in architectural representation in order to illuminate problematic assumptions that dominate the discipline’s methods. “Much of my practice focuses on operating in public space and concentrating on the direct and visceral qualities of those experiences,” she says. “In some ways, those concerns can get neutered or left out when we think about architectural representation, which becomes very abstract. It’s important to be rooted and embedded in our own bodies, to acknowledge that we’re not some kind of god behind a curtain constructing spaces for people that we don’t also live in. We’re of the world, and for architects to act like we’re not is a falsehood.”

Who we center as our subject is a really important question when we talk about architecture. Who is it for? Who gets to make it? Whose world view does it help prop up?

Jennifer Newsom

Architectural renderings, and the future constructions for which they serve as a translation, are not inert but prescriptive in that they present permissible orientations for bodies within spaces. In other words, they dictate where bodies can move and how, what they can see and from what points of view, and whether, in turn, those bodies can be seen. Unlike most theatrical scripts, however, in these designs the role of the subject has often been pre-cast long before drawing begins, usually as an idealized white, heteronormative, able, cis-male body. Positioning this subject as central to a design or even as the only possible subject at best effaces those not considered proper subjects or recognizable bodies and at worst facilitates harm, both physical and psychical, against them.

A Cartesian approach would suggest that an inherent and universal truth exists behind the symbols used in such renderings, but phenomenology illuminates the tensions these seemingly benign orientations may contain and subsequently manifest in the built world. “Phenomenology asks us to be aware of the ‘what’ that is ‘around’ [the body],” writes Sara Ahmed, a British scholar working at the intersection of feminist theory, lesbian feminism, queer theory, critical race theory and postcolonialism. Everyone does not engage the ‘what’ identically, though. Ahmed references the feeling of “comfort” as an example of such differences. “To be comfortable is to be so at ease with one’s environment that it is hard to distinguish where one’s body ends and the world begins. One fits, and, by fitting, the surfaces of bodies disappear from view,” she observes fA . For most white bodies in the United States this feeling is de rigueur and accepted as a natural state of being. Whether walking by a police station, entering a concert hall, or running across the street at night, a white body can, more often than not, move through space seamlessly, even invisibly, as it and the space around it mutually influence and interact with each other. Its movements can seem unlimited, and it does not pay attention to being seen or of its ability not to be witnessed.

A Black body—especially a Black body adorned by symbols or moving in such a way marked suspicious by white bodies—is not an actor with power and privilege in the same spaces, however, but an object by which white bodies orient themselves. According to the French-Martinican psychiatrist and philosopher Frantz Fanon, the familiarity with one’s world determines a body’s ability to do and find things. A world that does not engage in a mutually constitutive relationship with its subject, a world in which that body lacks agency, transforms that subject into an object by which others orient themselves. That body becomes an object acted upon rather than a subject with agency, a body lost and unable to find its footing.

Rudolf von Laban (right) and his dancers, Ascona, 1914. Photo Johann Adam Maisenbach. Courtesy Estate of Suzanne Perrottet.

It is in this way, Ahmed argues, that whiteness exists: not as a race codified by perverse scientific fantasies, but as a kind of amniotic fluid through which white bodies and those that assimilate to their codes flow freely. It homogenizes them but also “makes non-white bodies feel uncomfortable, exposed, visible, different, when they take up this space.” Thus a Black or brown body (or a woman) could never assume the role of Baudelaire’s flaneur—the stroller who observes modern society from a detached position. “Who we center as our subject is a really important question when we talk about architecture,” Newsom says. “Who is it for? Who gets to make it? Whose world view does it help prop up?”

One of Newsom’s goals in the studio was to make students acknowledge up front that subjectivity and the experiences it does and does not enable affects the work they do. In order to facilitate that awareness and how it manifests in design, she asked students to perform walks in their environments, which were varied because of distance learning. “I gave them a list of prepositions such as

on, between, against—words that are a kind of bridge in language and that have a spatiotemporal aspect,” she explains. “They picked five words and used them as intentions to guide their movements. They then made drawings representative of these qualities.” The objective was to make students aware of their own privilege or lack thereof, especially in public space, and of which spaces were and were not available to them. “It’s been interesting to hear them reflect on what’s afforded to them by their different environments and to use that experience as a provocation to think about race, the ableness of the body, gender, and the intention of a body in any particular space. You don’t build empathy outward if you don’t have a self-reflective capacity.”

Consider, as an example, the preposition

out of in relation to the Jefferson grid. Embodying Enlightenment ideals of imposing order on what was deemed an untamed landscape occupied by “savages,” the grid became a tool of settler colonialism in its attempt to dominate land that did not belong to them. Furthermore, the grid’s straight repeated lines—a declarative and predetermined cartography—illustrate power’s resistance to discomfort, surprise, and uncertainty by its elimination of difference. Anyone who did not capitulate to this form could be cast as a renegade and improper—even wild. Its straight lines also facilitate clear sight lines which, as Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon illustrates, can in themselves pacify bodies into obedience through a persistent assumption of being visible and therefore watched.

It is a challenge, then, to put oneself

out of view in the grid, to resist visibility, without the risk of being othered and turned into an object. The modern surveillance state has turned our spaces into a grid writ large and has made invisibility, in this sense, almost impossible. As a result, we have all been objectified in a way—though some more so than others. But how often is surveillance’s omnipresence, whether the literal vectors of security cameras and their phenomenological effects on individuals moving through space (stress, fear, etc.) or simply as a quality inherent to the grid, incorporated into architecture renderings?

Pope.L, “Tompkins Square Crawl,” (1991). Courtesy The Museum of Modern Art.

“If there’s a reliance on the truth of the line, how do we subvert that in some ways? Is it something about a density of marks? Redaction? A lack of visibility? A refusal of interpretation? Whether it’s fine to be oblique and not communicate? How do we layer the accretions of time, the fluidity of movement, its staccato rhythms, in the space of the drawing?” asks Newsom. Her students’ translations of their walks suggested novel responses to these questions of representational possibilities and limits in drawing. “Some are developing a kind of notation, almost like Laban dance notation, in which they make correspondences between movements and marks,” she says. “Others are looking at stereoscopic vision—the fact that we have two eyes. Those students did an interesting animation which explores moiré effect and the way in which our eyesight involves light hitting two receptors and the brain processing it in order for us to understand the three-dimensional world.”

As a further effort to inspire alternative possibilities in representation, Newsom then asked students to engage with a diverse group of artists whose work challenges hegemonic flows through movement, film, dance, and photography, as well as drawing. For example, for decades, the American artist William Pope.L performed long-distance crawls throughout New York City and Europe. In

Tompkins Square Crawl (1991), he wore a business suit while carrying a small potted plant, as if he were on his way to work. The piece illuminated that just to crawl—to refuse walking, verticality, and thus the dominant point of view and means of mobility in society—was enough to disrupt, to draw attention, and even to have movement stopped. In fact, an onlooker became so irate that he called the police.

Renée Green also plays with our ability to ignore the visible in her 1992 work

Mise-en-Scène: Commemorative Toile. By appropriating the 18th-century toile fabric tradition, which was produced by colonized peoples and often depicted colonizers and the colonized alike in bucolic scenarios, Green comments on Empire’s violence and its effacement of the Other. From a distance, Green’s delicate floral patterns seem to preserve toile’s traditional pastoral peace. Upon closer examination, however, one sees the lynching of a Frenchman, an enslaved Black man chained and kneeling in front of a white man, and other brutal scenes. The work could be read as a castigation of actions that purport to acknowledge problems but suggest no systemic changes—literal window dressing that asserts surfaces’ capacity to preserve power and the need for change to be more than skin deep.

Conversely, Janet Cardiff engages with the non-present and invisible in the scripted, choreographed walks she produces with George Bures Miller, such as

Night Walk for Edinburgh (2019). Participants are guided by Cardiff’s voice through headphones from which myriad street noises also emanate as they follow a prescribed path through the city. They hold smartphones which play scenes from a film shot on the same streets they traverse—a woman running down an illuminated path; drunk men singing as they pull a man, perhaps dead, on a trolley—creating a kind of augmented reality. Cardiff describes the experience as similar to that of recalling a dream when you wake up, with various scenes and characters that you might remember in full or just in pieces.

Location photograph for “Night Walk for Edinburgh,” (2019). Courtesy Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller.

By incorporating a sense of play into these interactive performances, and paradoxically through the use of technology, Cardiff compels us to pay closer attention to our physical environments, and specifically to absences therein. Through the haunted and haunting medium of film, she makes explicit that our environments are archives of memory and receptacles of loss. From a design perspective, her films prompt questions regarding the acknowledgment of time passing, such as the continual attempts to erase historical memory through repairs of surfaces as opposed to allowing them to reflect the passage of time. They also examine the continual attempts to erase such memory through repairs of surfaces, as opposed to allowing these surfaces to reflect the passage of time.

In part due to film’s incorporation of time—which separates it from drawing—Newsom assigned students to synthesize what they learned from their earlier explorations by creating short films using their own prompts, with a maximum length of three minutes. “In my practice, we do a lot of collaborations with filmmakers as a way to help us reinterpret, more deeply understand, and interrogate our work, but much of that happens after our installations are built,” she says. “I was interested in seeing what would happen if film is foregrounded in the architectural process, in what ways it could comment on how we represent, say, weight, slowness, effort, or exertion, and how those actions interact when executed in space as well as how others react to them.”

With these varied exercises Newsom hopes to inculcate a heightened awareness of the unconscious and conscious attitudes and tools that students bring to their work. “This is one of the last advanced studios for students before they do their theses,” she says. “They’ve been given an inheritance through their education to this point, and I’m asking them to think about what they do with it.” This “inheritance” is akin to Marx’s theory of history. “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past,” he writes in

The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. “We’re all physically in the world and are taking in the directness of experience in the moment, but we also bring our inheritance with us into those spaces,” Newsom continues. “Operating as a designer is no different. There’s a physical reality of what you’re creating but there’s also the intention that you bring to it and the inheritance that it carries with it before you’ve even arrived. There are physical and material realities of the world and conventions in which we operate, but the question is how we work with, alongside, and against them.”

It would be too idealistic to say that we can refuse the gifts of inheritance. Resisting and transgressing the expectations of the gift giver, however, is a conscious act, and an act that we ignore at our peril.

This Land Is Your Land: Students interrogate why “urban” and “Indigenous” are cast as opposing identities

This Land Is Your Land: Students interrogate why “urban” and “Indigenous” are cast as opposing identities

Until the last decade, Native American, First Nations, and other Indigenous architecture has been a glaring gap in North American architectural discourse. The increased recognition of Indigenous peoples and their continued push for self-determination, however, puts a spotlight on land use on Indian reservations and in other areas with large Indigenous populations.

Image from NACDI Leadership Training Program: An annual training program focused on developing highly skilled and committed Indigenous leaders.

, associate professor in practice of urban planning at the GSD, asked students to engage with Indigenous architectural issues in two sequential studio modules this term. The first—

“This Land Is Your Land”—focused on Minneapolis, which was built on land stolen from the Dakota tribe.

Minneapolis’s Native American Community Development Institute (NACDI) hopes to bolster the growth of the country’s only America Indian Cultural Corridor in a city home to one of America’s largest urban Native American populations. The second studio (which is still in progress)—

“As of Right: First Nations Reclaim the City”—looks at British Columbia, where the Squamish Nation seeks to build diverse new projects on its undeveloped reserve land, including 11 acres of the former fishing village Senakw, which lies within Vancouver.

Historically, “urban” and “Indigenous” have been cast, psychically and physically, as opposing identities. Indian reservations in the United States—of which there are about 300 in 36 states, comprising over 50 million acres of land—were intentionally situated away from metropolitan areas and especially in areas not deemed desirable by white populations. This enforced isolation reinforced the long-held colonialist project, both conscious and unconscious, of removing these societies from those of the settler colonialists by separating them from roads, cities, towns, and, in some instances, natural resources. While the Indian Relocation Act of 1956 brought more than 100,000 Native Americans to urban areas, it did so with an assimilationist agenda. It sought to eliminate Native American identity through the intentional severing of family and community ties which the federal government saw as counterproductive to promoting American nationalism after World War II.

“Conservative terminationists [the term used to describe those who supported these assimilationist policies] saw traditional Indian communal social structures as too similar to the dreaded communist systems that they perceived the United States to be in conflict with during the Cold War,” Larry W. Burt writes in American Indian Quarterly. “Separate governmental and landholding status, federally-supplied services, and the continuation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs itself violated a politico-economic system based upon individual property rights and private enterprise that conservatives saw as the foundation of the American system.” Today, up to 72 percent of Native Americans live in urban areas, where they experience nearly twice the rate of poverty, unemployment, and under-education as the general population, with outsized homelessness rates as well.

In Canada, over half of the Indigenous population—First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples—live in cities. They, too, have historically been subject to a holocaust and the systematic annexation of their land—in large part, a result of the Indian Act passed by Canadian Parliament in 1876. The edict prohibited First Nations peoples from freely leaving their reservations, forming political organizations, speaking their native languages, and practicing their religion. Key to the federal government’s intentions to eradicate First Nations identities was the establishment of the residential school program, where abuse was also prevalent. A Truth and Reconciliation Commission formed in 2008 declared these schools a practice of cultural genocide.

The two countries’ relationships with Indigenous peoples have distinct differences though, particularly concerning land rights. Ninety-five percent of the land in British Columbia is “unceded,” meaning it has never been the subject of a treaty that gave it to settlers. “The City of Vancouver have been pretty progressive in some ways by acknowledging that the land is the property of the Musqueam, the Tsleil-Waututh, and the Squamish Nations. There is also a treaty process in British Columbia aimed at resolving First Nations’ claims,” D’Oca says. “Additionally, there are examples of First Nations reclaiming land through litigation and direct action, like in the case of Senakw, which is on highly developable, highly valued land in the middle of Vancouver. Because it’s an IR and Squamish administered, it’s not subject to zoning or the typical review process. Basically they can do whatever they want with it, which is why my studio is called ‘As of Right.’ While there remains a ways to go regarding these lands, this is a precedent-setting project and exciting that a First Nation was able to reclaim land in a major city. It may be a preview of what’s to come in the States.”

Considering this violent and exclusionary history, concerns about non-Indigenous architects working on Indigenous-related projects are legitimate. But these may be overcome through understanding and cooperation. The former begins with acknowledgements of recognition—of cultural identities and land ownership. “‘Native American’ is a huge umbrella term that in some ways has very little meaning,” D’Oca acknowledges. “The differences between tribes in the States and between the Nations in Canada are just as important as their similarities.”

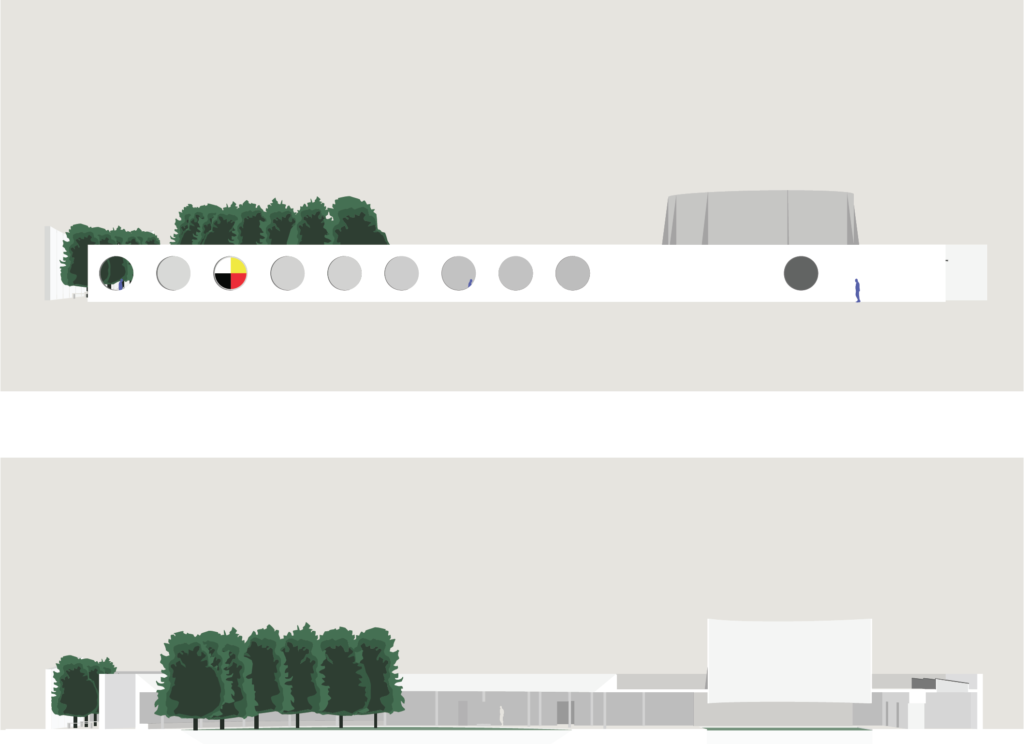

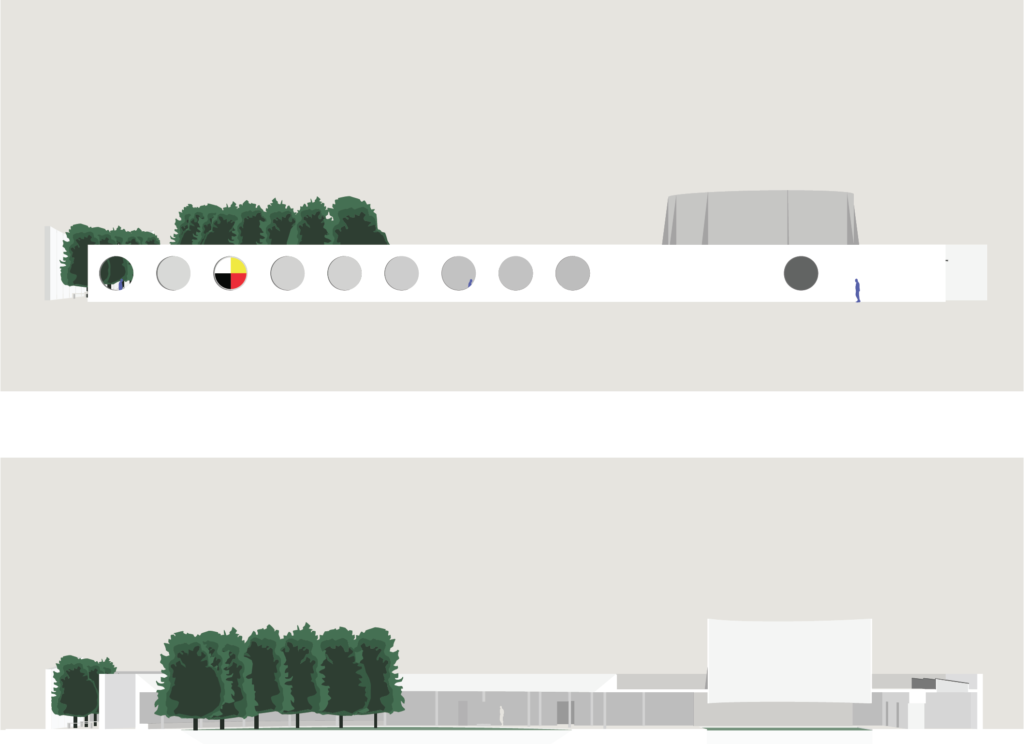

Elevation and Section by Kyle Winston(MArch I ’22) for “This Land Is Your Land,” Dan D’Oca Urban Planning and Design M1 Studio

In terms of cooperation and collaboration, the most productive genesis of a project is an invitation from a community. “I believe strongly in the philosophy ‘nothing about us without us,’” D’Oca says. “In my classes, we always strive to do as much engagement as we can with people who hold diverse opinions. For both studios, we set up a series of discussions with people who work in the neighborhood, leaders who are in touch with the desires and needs of the people in the community, and our client.” For the Minneapolis module, this included

Louise Matson, executive director of the Minneapolis-based Division of Indian Work;

Kelly Drummer, President of MIGIZI Communications, a local Native multimedia arts and youth mentorship organization; and Becky Wolf, a community embedded librarian at

Franklin Library, located on Franklin Avenue which serves as the principal artery of the

American Indian Cultural Corridor. “I don’t let students pick a project until we’ve heard a lot of different voices,” D’Oca says. “The idea is for students to listen, hear what the problems are and what people are working towards, and figure out what they can do to help.”

“These courses teach students how to engage in respectful dialogue,” says Heidi K. Brandow, a founding member of the Harvard Indigenous Design Collective (HIDC) and one of D’Oca’s teaching assistants. “The students are learning how to develop these kind of relationships, to listen, to work in tandem with these communities, and also to learn and understand Native communities’ contributions to the land from design, architectural, and planning perspectives. These conversations could potentially lead to long-term solutions.”

Also key to avoiding a practice of architecture-by-imposition that continues the violence and paternalism of settler colonialism is the studios’ engagement with goals brought by the stakeholders themselves. Unlike the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which long instituted plans that did not address the culture and needs of those who occupied those spaces, D’Oca’s students work from ideas suggested by locals. “For the Minneapolis module, NACDI had composed a document that expressed the priorities of the Native peoples from the neighborhood,” D’Oca says. “We knew they wanted an Indigenous farm, a center for Indigenous cosmology, job training, better transportation, and affordable housing. As a result, students were able to say, for example, ‘I know something about affordable housing, and while I’m not going to be the one to put the shovel in the ground, I can help move the needle.’”

Kyle Winston (MArch I ’22) drafted a solution to the separation of urban life and ceremony. He cites a decades-long ban in Minneapolis that pushed Indigenous peoples to the countryside to perform their sacred rituals as a principal reason for NACDI’s request to bring ceremony into the cultural corridor. Winston’s project calls for the creation of “new grounds circularly inscribed within a rectangular site on Franklin Avenue” which include a mix of gathering and sacred spaces. An initial opening in the southeast corner invites anyone, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, to enter, while paths lead toward the site’s center where, he details, “[In] a cloistered garden, three of the four sacred medicines are grown: tobacco, sweetgrass, and sage.” In this space, “an exaggerated soffit directs one’s attention down to the plants, while up above, the sky is pushed away [and becomes] an object of contemplation.” “Red cedar trees (the fourth sacred medicine) frame the ceremonial activity, buffering the city’s hum beyond,” Winston continues, furthering the blend of publicness and privateness in an architecture that resists turning ceremony into a tourist attraction while also educating the uninitiated.

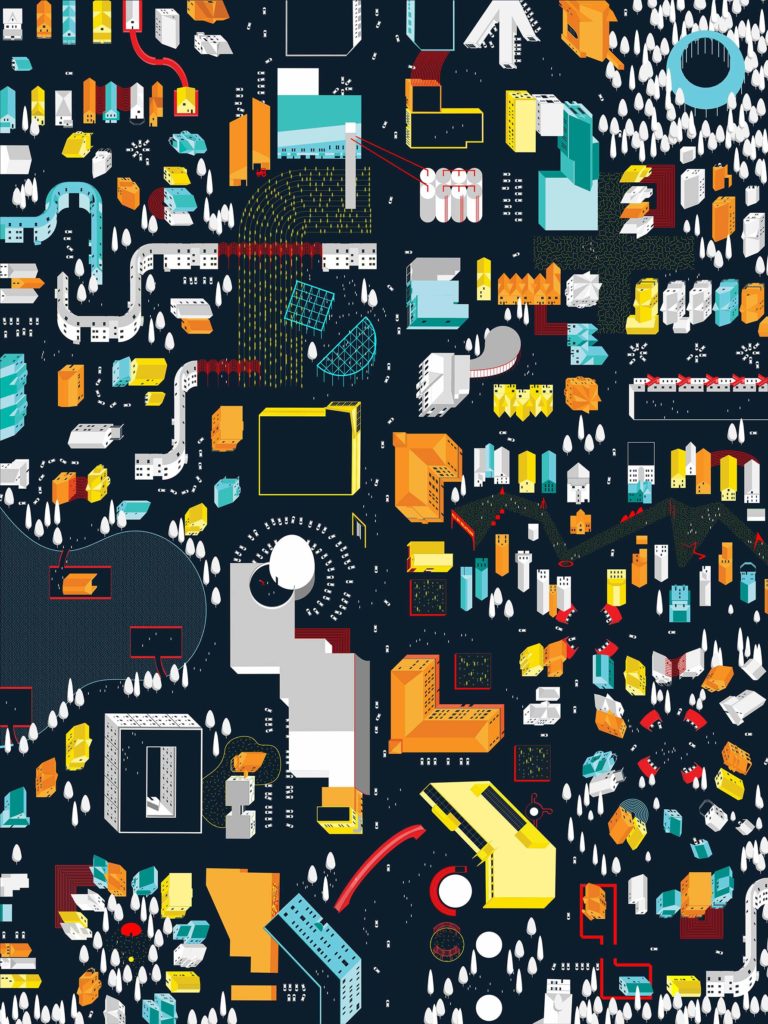

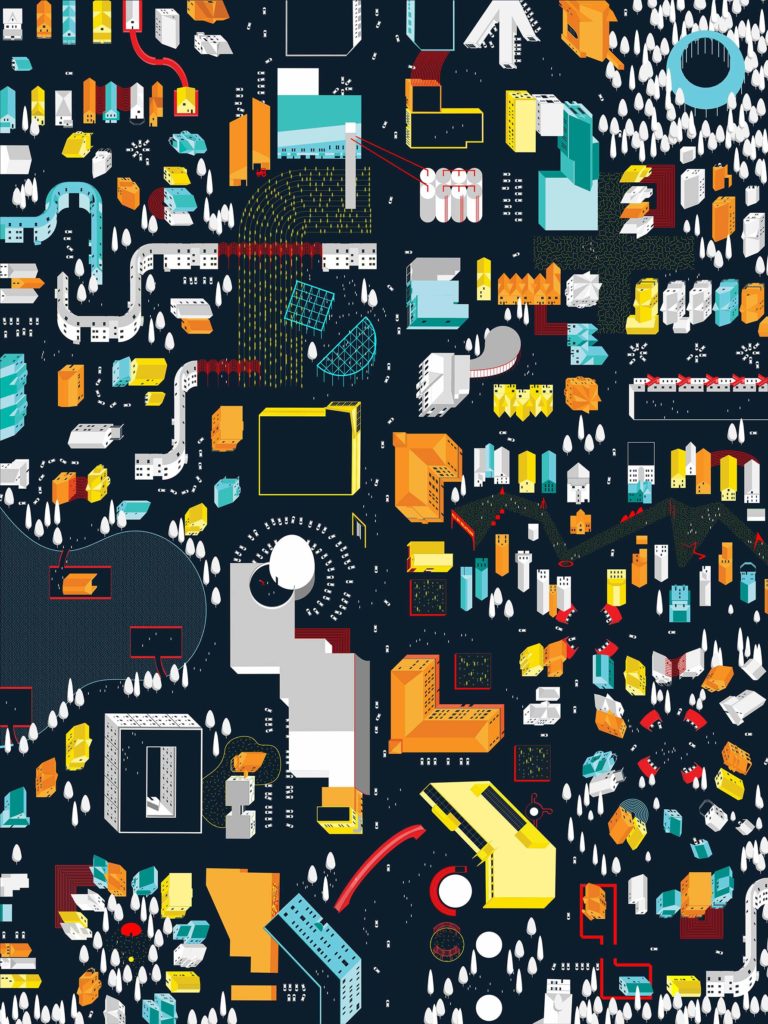

Map by Rachel Coulomb (MArch I ’22) for “This Land Is Your Land,” Dan D’Oca Urban Planning and Design M1 Studio

Rachel Coulomb (MArch I ’22) drafted a more speculative proposal by interrogating the colonizer’s violence against Indigenous peoples using property lines. “The Dawes Act of 1887 authorized the federal government to break up tribal lands by partitioning them into individual plots. Only those Indigenous Americans who accepted the individual allotments were allowed to become US citizens,” she notes. She proposes turning the land into a community trust instead, “where future programming is an agreement among those that live there, and power is placed back with the people through an environmental and social stewardship model.” The result, Coulomb argues, would be a “counter-cartography” that turns Minneapolis into “an expression of generational Indigenous values” and the map into “a depiction of stories” rather than an enemy.

Beyond the respect for the stakeholders in the community this approach entails, it also promotes a tempering, or even dissolution, of ego for architects and designers—an ethos that could be adopted in all interactions with clients, especially with those from cultures unfamiliar to one’s own. A new mode of design that speaks to architectural concerns broadly, with which non-Indigenous designers can provide assistance, while upholding specific cultural traditions may emerge as a result. Such creative collaboration, grounded in dialogue—and, arguably more importantly, listening—can synthesize diverse perspectives and lead to mutual education and growth for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups. “Pooling our resources at the GSD to create solutions is mutually beneficial,” says Brandow. “The Native communities benefit from hearing about these proposals, and I hope that the students will walk away with a deeper understanding of Indigenous people and will want to continue working with them.”

With Mass Timber and the Scandinavian Effect, Jennifer Bonner and Hanif Kara speculate how wood might recapture the American architectural imagination

With Mass Timber and the Scandinavian Effect, Jennifer Bonner and Hanif Kara speculate how wood might recapture the American architectural imagination

Moments of intense constraint have driven architecture toward seismic ruptures, which go on to determine how people build and live for centuries. We are within one such moment today. As a pandemic forces communities across the world to reconsider how and where people assemble, questions arise around how to augment the built environment accordingly, and which of these augmentations become new paradigms.

Events like this punctuate history. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 ruptured American architecture in ways that would directly shape the 20th-century city. After fire had charred many of the city’s wood-constructed buildings (and sidewalks), building code was updated to favor flame-resistant materials like brick, stone, and steel, which then became rudiments of urban skylines. Within a decade, the earliest steel skyscrapers started rising; a new type was born.

A century and a half later, wood has started looking good again. As designers have toyed with how wood might recapture the American architectural imagination, one format has arisen as a steward: mass timber (“mass” as in “massive”)—a generic term that includes wood-based material of various sizes and functions, including familiar glue-laminated (glulam) beams and laminated veneer lumber (LVL).

But it’s cross-laminated timber, or CLT—boards of wood glued together in perpendicular stacks to create a thick block—that has truly ruptured the canon. “Builders see [CLT] as a way to construct midrise structures faster and cheaper,”

wrote the

Washington Post last year. “City planners see a fast track that could help reduce housing shortages. Architects love its light weight and look. And some environmentalists tout its ability to lock up carbon to combat climate change.”

Jennifer Bonner and Hanif Kara speculate on the possibilities of a so-called “Scandinavian Effect,” fueled by mass timber and the new lenses it offers on material and structural advancement, constructability, and form.

CLT arose as a popular building material in Europe throughout the early 2000s, especially in Scandinavia. Canadians started building with it before long. This past November,

Archinect revealed Mitsui Fudosan and Takenaka Corporation’s plans for a 17-story, 70-meter-tall wood-frame office building in Tokyo, which would become the tallest wooden building in Japan.

CLT’s American invasion has been hampered by the nation’s highly prescriptive building code—one legacy of the Great Chicago Fire—and by the near-ubiquity of stick-frame construction. But as wood, and CLT in particular, has attracted more interest in recent years from designers, developers, and builders alike, United States industry regulations are starting to follow suit. “Developments in code are happening right now with mass timber within the US,” observes

Jennifer Bonner, associate professor of architecture at the GSD. Bonner would know—she recently cast CLT as the star of her

first built project, Haus Gables, a two-story house in Atlanta, Georgia.

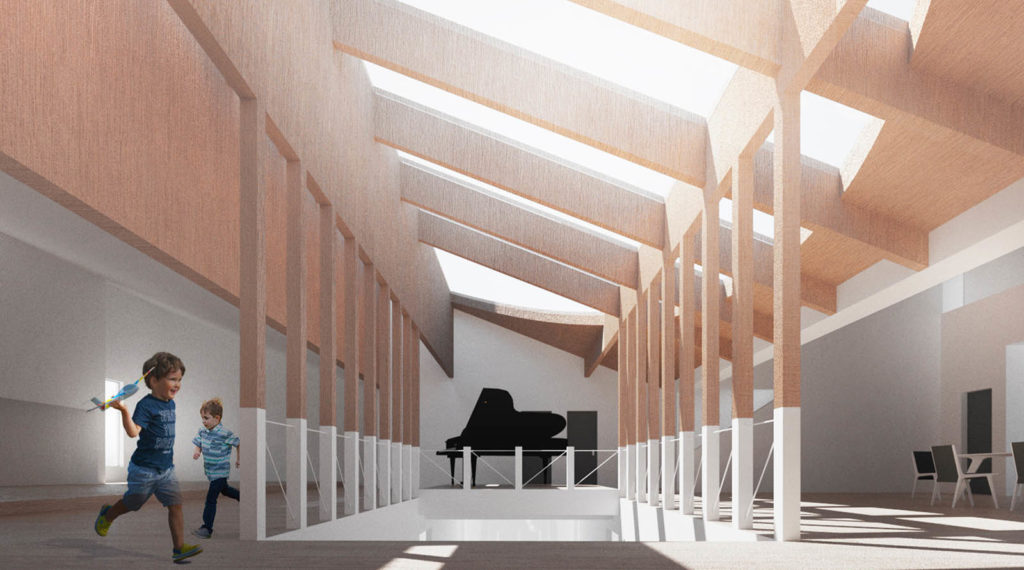

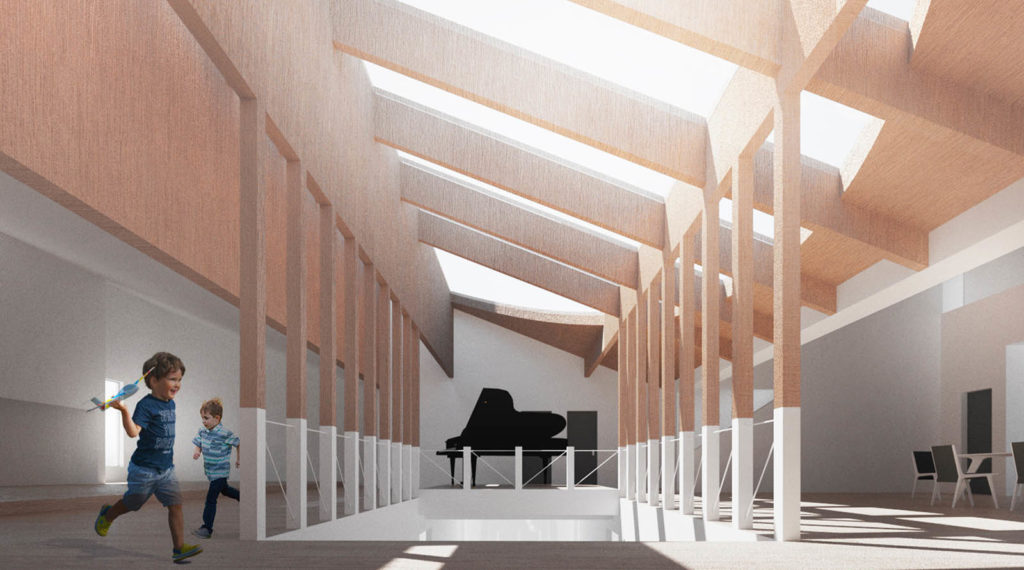

Interior view of Jennifer Bonner’s Haus Gables

With Haus Gables, Bonner questioned the very rudiments of how architects design, and inspired a closer look at CLT’s potential to generate new types or effects. She tackled the CLT challenge alongside project engineer Hanif Kara, professor in practice of architectural technology at the GSD, and a longtime mentor.

While engineering Haus Gables, Bonner and Kara hatched “

Mass Timber and the Scandinavian Effect,” a spring 2020 studio that framed CLT within questions of cultural instigation and identity alongside the material’s physical properties. Bonner and Kara speculated on the possibilities of a so-called “Scandinavian Effect,” fueled by mass timber and the new lenses it offers on material and structural advancement, constructability, and form. They point to parallel currents: the Bilbao Effect—that city’s reinvigoration via a new cultural nexus, the Guggenheim Bilbao—and the Dubai Effect—architectural illustrations of free-market capitalism via gravity-defying skyscrapers.

To test these speculations, Bonner and Kara wanted to apply the Scandinavian Effect to a tabula rasa of sorts—the American South—and see what might stick. “Suddenly the students couldn’t make a purely Scandinavian architecture, but it became something other quite quickly,” Bonner says. Weeks of dialogue and iteration led the studio to speculate on CLT’s potential in new and varied settings. Prompted to design both a house and a mid-rise tower in Raleigh, North Carolina, students experimented with and forecasted where and how CLT may expand its roots.

Tectonic Shifts

Bonner had planned to be on-site for construction of Haus Gables. Instead, a travel snafu grounded her in Cambridge, and left her monitoring a security-camera feed as 11 trailers delivered 87 CLT panels. “The whole thing looked like an architectural model being assembled in place,” Bonner recalls. “If you squint your eyes, watching the panels being installed at that scale, one could imagine: This is the way we cut up materials—chipboard, foam core, and whatever else is on our desks—and make models.” In fact, the house was snapped together much like its

miniature cousin,

The Dollhaus, the intentionally scaled 1:12 model, which Bonner had created as a research iteration through her design practice, MALL.

For the studio, CLT’s diverse characteristics established it as a prime representational canvas for testing architectural possibilities: It can evoke both paper-thin origami and big-block Brutalism; it can be folded and manipulated, but can also withstand extreme weight and pressure; it lends itself to experimentation and play, but begets intense precision and calculation.

The students spent the first few weeks getting to know their new material a bit better. Aryan Khalighy (MArch ’21) began his experimentation with a crude test: he watched empty cardboard boxes fall and stack themselves under simulated gravity, producing a pile of nested mass that appeared like an irregular tower. Similarly, Edgar Rodriguez (MArch ’20)

conceptualized CLT as piled-up mass, from which he realized the opportunity to experiment with the underbelly of the roof. Calvin Boyd (MArch ’21) started the design process for his “Notch House” with a single roof gable, which he then multiplied, creating both added interior space and a central CLT core. Boyd cut treads and slots into that core, generating a stair column that bears the rest of the house’s CLT structure. He describes the effect as one of levitation, illustrating CLT’s ambiguity between heavy and light. (Bonner, too, “started from the roof” with Haus Gables.)

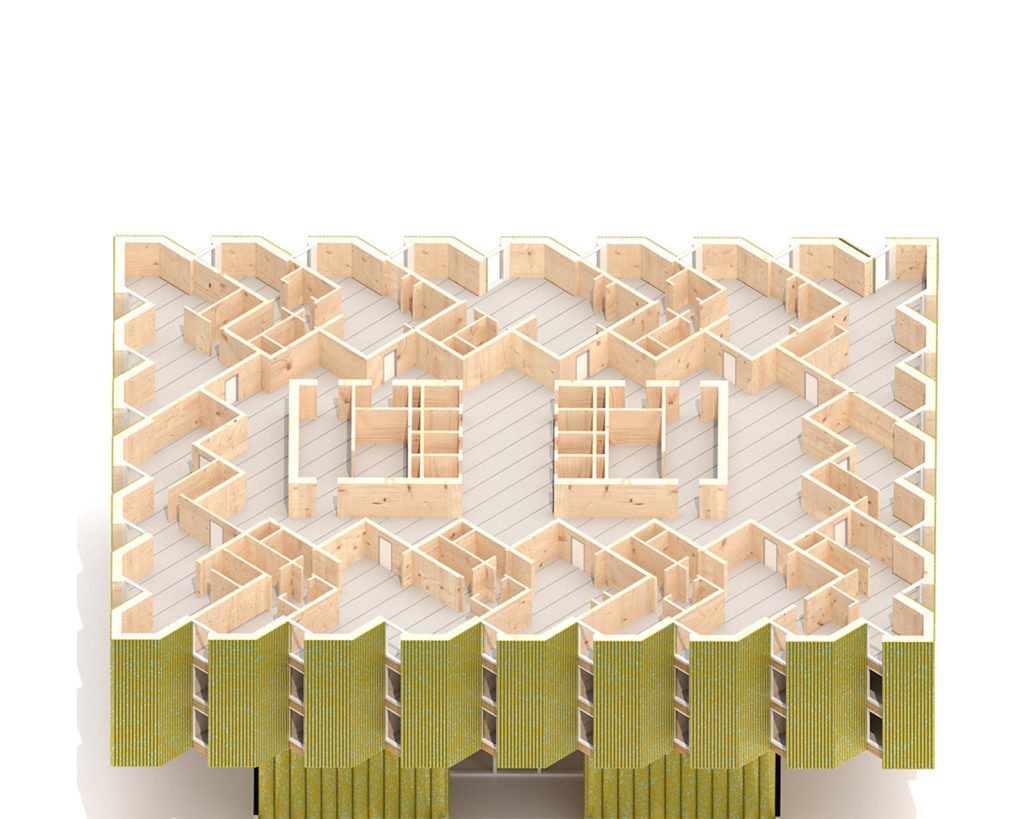

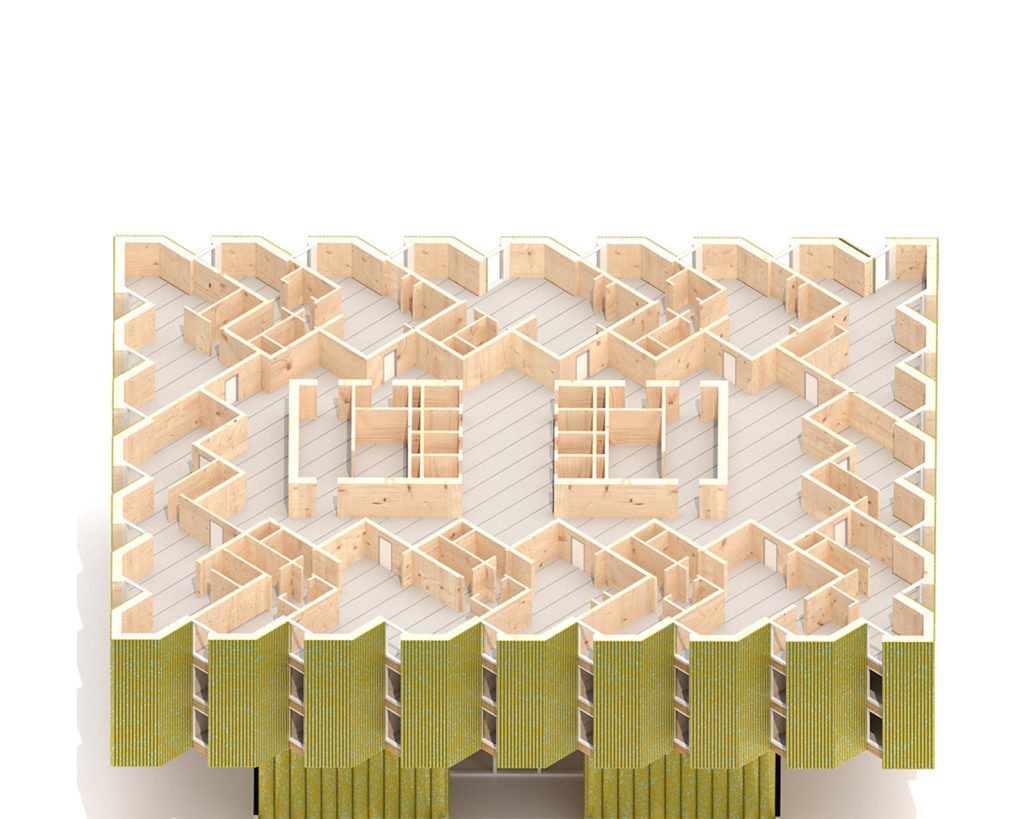

Others identified different tectonic opportunities around which to organize the house. Benson Chien (MArch ’21) looked to the inner-wall spaces that result from traditional “balloon framing”—the use of standard two-by-fours to generate a house’s cubic skeleton. Chien wondered if, instead, layered CLT panels could generate a different wall structure, if not a new typology.

Each of these designers used so-called CLT blanks—structural sheets composed of three-ply, five-ply, and seven-ply CLT panels—as their main ingredient, exploiting the opportunity to play with stacking and layering. Chien’s shotgun-style “McMansion” stacks layers of CLT to form walls, then carves openings in the CLT blanks that serve as both windows and room thresholds. Aesthetically, Chien translated “suburban kitsch” from surrounding homes to the CLT blanks and cutouts of his McMansion, acknowledging the marching spatial rhythm of the shotgun-house typology while metabolizing the house’s surroundings.

Calvin Boyd’s “Notch House” achieves effects of lightness and levitation via CLT blanks

“On the scale of the panel, one can remove portions of the CLT blank to easily create unique apertures or carve out layers to form custom interior patterns,” observes Ian Grohsgal (MArch ’21). “On the larger scale of multiple panels, one can take advantage of the ready-made quality of CLT to arrange them in unique patterns and to create larger readings.”

Anna Kaertner (MArch ’21) applied CLT blanks to so-called accessory dwelling units—self-contained apartments within an owner-occupied home, either attached to the main dwelling or in a separate structure—interrogating the tendency for the larger house’s structural hierarchy to predominate. Kaertner’s “Big/Little House” centers a staircase that creates a shared skylight for the two houses. She reimagined the roof as beams instead of planes, with interconnecting logs generating a scalloped roof. The resulting curved wall binds the two houses in elevation, generating two sides—one smooth, one serrated—and revealing a new CLT grain through aggregation.

“CLT is an extremely malleable material, and its expression does not need to be planar,” Kaertner says. “Irregular geometry and curves do not produce labor- or materially-intensive processes because the geometries are produced at the same moment and use the same process that produces CLT itself. This makes it possible to seek out these new expressions for connection and structure.”

House design offered an organic testing ground for CLT—after all, wooden houses dot America—but wooden towers remain an anomaly. Despite this, CLT’s ability to bear weight qualifies it as an apt ingredient for the American tower. Anna Goga (MArch ’20)

designed a mid-rise that embraces CLT’s sheer bigness and suggests how the material’s format could generate an entirely new tower typology.

Goga began with simple cuts into CLT blanks, using small pieces of steel at each cut to conjoin pairs of panels. After 400 slices and 400 bandages binding 300 panels, Goga generated an exoskeleton in which the facade line sits

inside the tower. This CLT tube comprises four 24-meter-tall zones with a gantry system of cranes built into each of the four ceilings, allowing for reassembly of floor plates and walls with endless variations. (Here, Kara raises a precedent: Google’s European headquarters in London’s King’s Cross, which offers the largest CLT floor in Europe, a floor that is entirely removable or changeable over the building’s lifespan.)

“We come to an interesting point where a CLT blank encourages us to customize the building three-dimensionally,” Goga says. “I was exploring the idea of the after-life of a building and the possibility to reassemble it from the inside, which is potentially possible with light and easily assemblable CLT panels.”

A unit plan of Khalighy’s tower reveals a “sort of mini-suburbia”

As CLT’s tectonics offer the enticement of “scaling up” such reassembly and reconfiguration, designers see grander opportunities for rearrangement or reconsideration of design typologies. Reviewing Khalighy’s CLT tower unit plan, GSD professor

Oana Stănescu noted a “kind of mini-suburbia” emerging—a suggestion of such interplay between CLT tectonics and larger-scale typologies.

Customizably Unexpected

While Khalighy stacked cardboard boxes, Hiroshi Kaneko was carving paper snowflakes. “With early study models, I took advantage of our inclination as architects to use thin, easily workable paper,” says Kaneko (MArch/MDes-HPDM ’21). After leaning paper sheets against each other, he trimmed corners in ways that allowed the paper to retain planarity while introducing subtle, two-dimensional curves, gesturing toward the CNC technology used to machine-cut CLT panels.

“This studio gave us the opportunity to bring to CLT what steel and concrete already benefit from: boundlessness,” Kaneko observes. “The work of this studio, the work of bringing new metaphors into building materials, helps lift the bounds we impose upon materials and opens us up not necessarily to better design but to new technologies that can support our imaginations.” In “Cutting Corners,” Kaneko’s tower proposal, the facade presents what he calls “coherent whimsy” and “allied composition” of patterns, taking advantage of two CLT characteristics: the ability to carve cutouts and textures, as well as the aggregation of wood-grain patterns.

“This studio gave us the opportunity to bring to CLT what steel and concrete already benefit from: boundlessness,” Kaneko observes

Applying digital precision at enormous scales threaded the studio’s speculation; both Goga’s and Kaneko’s exploration of CNC technology, for instance, inspired a broader, more programmatic concept of rearranging entire buildings.

Elif Erez (MArch/MDes-HPDM ’22) traced CLT duality—massive in scale, yet customizable to extreme precision—to its essence: CLT begins its life span as whole wood that is broken into smaller pieces, then stacked and aggregated into CLT form. “I think the CLT blank has a kind of deadpan humor to it,” Erez says. “It is both sheet-like and massive, and when used in the way that one is accustomed to using sheet materials, it does unexpected things with scale and effect.”

In Erez’s house proposal, “

Barn för Barn,” an A-frame volume floats atop three smaller volumes, which in turn form the entryways into three separate housing units, divided by two sets of walls that double up to house bathrooms, kitchen, and storage. As the A-frame volume is raised, the ground floor becomes a shaded outdoor space, offering a collective playground for the three housing units above. Forming three different foundations and entrances, CLT blanks read as simultaneously small and enormous.

Erez scaled-up “Barn för Barn” for her tower proposal, “Barn, Barn, Barn för Barn,” by designing a floating window grid and three cores that support 70 percent of the tower’s vertical load. Erez applied the same system in the house as she did the tower—CLT as shiplap siding—with the effect appearing gigantic on the tower when compared to its traditional use on houses. Each core of the tower offers a component for collective childcare, while main program is pushed to the building’s edges. The tower, with its brushed metal facade, points just a bit off the perpendicular street grid, creating a triangular orientation. The effect is a tower that offers heterogeneous spatial and programmatic possibilities, and a moment in which the domestic and the urban meet and meld.

Kyat Chin (MArch ’21) probed structural opportunities by designing a tower with a rotational wall system instead of a table. Like others, Chin played first with stacking of CLT blanks and spaces; the four generic table types that resulted were then scaled, stacked, and nested in various configurations, achieving column-free plans to accommodate various programs. One effect, Chin says, is illusions of “rooms within rooms.” Chin cladded the tower’s facade with Canadian cedar shingles and anodized aluminum, blending the domestic and the industrial to reinterpret tower aesthetics.

Like Erez, Daniel Garcia (MArch ’20) presented an askew tower—in his words, “slightly misbehaved”—adapting a generic post-and-beam form into what he describes as an exploration of the post-digital at the tower scale. Intended as an art and design school for Raleigh, Garcia’s tower complicates generic form with the sort of hyper-precise digital editing that CLT construction enables. For his house project, Garcia rearranged the Southern “dog trot” typology to suggest a new form: he adapted the dog trot’s main feature—a long breezeway—and split, then offset, the house along that axis, taking advantage of CLT’s distance-spanning properties. He also stamped the house’s asphalt shingles with an embossed image of wood.

Studio colleague Edward Han (MArch ’21) observes that the ability to color-stain, emboss, and cut patterns into CLT means that it can act as a “contemporary kind of ‘wallpaper’ and ornament.” With aesthetics a central studio consideration, this CLT characteristic offered particular excitement. “For the first time,” Han says, “we have a structural material that can be perfectly cut, mitered, shaped, and fenestrated with a CNC machine, offering endless possibilities.”

Instigating Sustainability, and other Perpetual Effects

In testing CLT against images of domesticity and the American South, the studio questioned how CLT’s unique properties might coalesce in creating a new Effect. Cultural readings interlaced studio proposals: suburban kitsch, log-cabin tectonics, “McMansions,” the traditional Southern porch, and American “bigness” found fresh expression. Traditional stick-framing emerged as an unwitting foil.

“Stick-framing relies on repetition of a particular type, producing houses that look the same: repeated American Dreams of previous centuries,” observes Peeraya Suphasidh (MArch ’20), who recently completed “

Wooden House” in Amboise, France. “CLT provides flexibility in terms of customization and gives the ability to do something unique and precise with shorter time.”

One theory behind CLT’s recent recognition has been consumer desire to see more wood. IKEA, for example, structured a 2015 campaign around “wood as lifestyle.” In the studio brief, Bonner and Kara point to IKEA’s Skogsta furniture collection, as well as Sam Jacob’s £30 Plank Scarf, as signaling the image of wood as on-trend. “Wood is often left exposed in mass timber buildings—it doesn’t need to be wrapped or bolstered to meet code—and there is nothing quite so beautiful as large expanses of exposed wood,” writes Vox’s David Roberts. “It is appealing on a primal level, a connection to nature.”

Amid urgent climate concerns, much CLT dialogue circles questions of sustainability. Wood-based buildings can be “carbon sinks,” many argue, absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Experts have speculated on the potential to reduce emissions in the building and construction sector (concrete produces

an estimated 5 percent of human-generated carbon dioxide emissions each year). They also expect that it can trim the waste, pollution, and costs associated throughout the construction process—arguing that CLT buildings are simply faster and cleaner to create. And while proponents wrestle with questions about deforestation and supply, Scandinavia has demonstrated that appropriate forestry principles can offset this balance.

The studio also approached broader questions of how, in its application to ongoing issues like housing shortages and

affordability, mass timber like CLT might present disruptive solutions. As such, CLT becomes a tool beyond materiality for the architect, inviting if not begetting a recharged agency for architects and a pull for closer collaboration with engineers, builders, artists, and others. Through such synergy, CLT offers designers the chance to not just design new buildings, but to provoke new typologies and ways of working.

“There is potential here for architects and designers to leverage the digital layer of prefabrication to make real-time decisions on cost, performance, and embodied carbon, among others,” says Lily Huang (MArch ’09), Associate Director of Building Innovations at

Sidewalk Labs. “Taking an iterative approach can create a more robust process, which leads to better buildings. Mass timber has the potential to catalyze an architectural movement that can define how we design and build buildings in the next 50 years.”

“This is the fascinating fact about CLT: it brings structure and architecture—since their divorce in the modern movement—back together,” observes Khalighy. “This is not a compromise on the autonomy of architecture. On the contrary, it expands the agency of architects and enables them to rethink the structural core of architecture through a collaboration with engineers. To have two instructors in our studio—Jennifer Bonner as an architect and Hanif Kara as an engineer—provided a fantastic environment for us to experience the negotiation between both disciplines, not only from a practical standpoint, but as an intellectual activity.”

“Mass Timber and the Scandinavian Effect” was led by Jennifer Bonner, Associate Professor of Architecture, and Hanif Kara, Professor in Practice of Architectural Technology, with Teaching Associate Nelson Byun (MArch ’15). The studio’s February 2020 site visit was generously supported by Sven Tyréns Trust.

These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays

These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays

The essence of the project is an implementation tool kit, which outlines each step of the process, from site identification and negotiating with landowners, to community management, financing, and final outcomes. While the tool kit is designed for broad application, the team chose Dell headquarters in Austin, Texas—a city with a high rate of renters and ethnic diversity—as its test case. The site currently has an excess of 2,000 parking spaces, which translates to 12 acres available to be converted into a mobile home community.