Yotam Ben Hur awarded KPF Foundation’s Paul Katz Fellowship

Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Yotam Ben Hur (MArch ’20) is one of two recipients of the Kohn Pedersen Fox Foundation’s 2020 Paul Katz Fellowship, an internationally recognized award that honors the life and work of former KPF Principal Paul Katz. The GSD’s Ian Miley (MArch ’20) was also recognized with one of two honorable mentions.

The KPF Foundation sponsors a series of annual fellowships to support emerging designers and advance international research. According to KPF, the Paul Katz Fellowship is given each year to assist international students in studying issues of global urbanism. The award is open to students enrolled in a masters of architecture program at five East Coast universities at which Katz studied or taught: Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Columbia, and the University of Pennsylvania.

KPF focuses each annual iteration of the Paul Katz Fellowship on a different global city. This year’s fellowship is tied to Mexico City; previous cities include Tel Aviv, Sydney, London, and Tokyo. Given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, KPF has announced that they will pause any travel requirements, and will distribute half of the $25,000 travel stipend as a financial award to each winner.

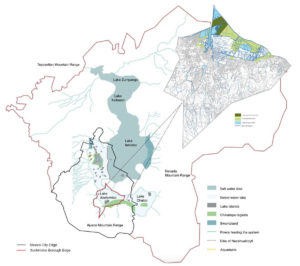

For the fellowship, Ben Hur submitted a research proposal examining the relationship between nature and architecture in peri-urban Mexico City with a concentration on the region’s informal settlements and their effect on the ecological water crisis the city is facing. Farshid Moussavi, professor in Practice of Architecture, was Ben Hur’s faculty advisor; Jacob Reidel, assistant professor in Practice of Architecture, and Eric Höweler, associate professor of Architecture, served as faculty reviewers.

“My proposal was ignited by the accumulation of different experiences and lessons I’ve gained while being at the GSD,” Ben Hur says. Reflecting on his proposal, he emphasizes the value of looking outward into the countryside rather than remaining focused on urban or familiar surroundings. He considered the complexities and challenges of designing living spaces for high-density environments characterized by informal development, as well as what he describes as “our constant battle with climate change, and our desire to find balance between the natural and the built environments.”

“Mexico City has entered a stage in which, on the one hand, there is a great need for public works, housing, and service infrastructure for the peri-urban poor, and on the other, huge pressures are being placed to conserve the surrounding environment on the verge of a climate crisis,” Ben Hur writes in his research proposal. “In this constant battle between architecture and nature, between the need to urbanize land and the desire to conserve and restore the landscape, architects and planners must intervene and redefine the relationships between the two entities, to end the loss and offer a solution of coexistence—an approach that does not separate the two realities, but rather sees the informal settlements and the natural, protected areas as components of the same ecosystem.”

Ben Hur and Miley follow a legacy of GSD students who have been honored with the Paul Katz Fellowship, including 2019 winner Miriam Alexandroff (MArch ’19) and 2018 winner Sonny Xu (MArch ’18, MLA ’18).

The KPF Foundation also organizes other fellowships, lectureships, and education-minded programs. Last year, the GSD’s Peteris Lazovskis (MArch ’20) was among three recipients of the KPF Traveling Fellowship, earning a $10,000 grant to support a summer of travel and exploration before a final year at school.

2020 Graduating Student Award Recipients

Each year at commencement, the Harvard Graduate School of Design confers awards to graduating students that demonstrate exceptional scholarly achievement, leadership, and service. Congratulations to all the 2020 graduating student award recipients!

School-wide Awards

Gerald M. McCue Medal: Karan Saharya (MDes Critical Conservation ’20)

The Gerald M. McCue Medal is awarded each year to the student graduating from one of the school’s post professional degree programs who has achieved the highest overall academic record.

Digital Design Prize: Jia Jung (MArch I ’20)

The Digital Design Prize is presented by the Graduate School of Design to the student who has demonstrated the most imaginative and creative use of computer graphics in relation to the design professions.

Plimpton Poorvu Prize: MacKenzie Wasson (MArch I ’20) for his submission Building Biras: A Hurricane Adapted Caribbean Resort

The Plimpton-Poorvu Design Prize recognizes the top team or individual for a viable real estate project completed as part of the GSD curriculum that best demonstrates feasibility in design, construction, economics, and in fulfillment of market and user needs.

Peter Rice Prize: Peteris Lazovskis (MArch I ’20)

The Peter Rice prize honors students of exceptional promise in the school’s architecture and advanced degree programs who have proven their competence and innovation in advancing architecture and structural engineering.

Sinclair Kennedy Traveling Fellowship: Elena Brigitte Clarke (MDes Critical Conservation ’20) for study in Italy

The Sinclair Kennedy Traveling Fellowships support a full academic year of research at destinations outside of the United States.

Fulbright Grant: James Carrico (MArch II/MUP ’20) for study in Hong Kong

The Fulbright US Student Program is an international exchange program in the fields of education, culture, and science, offering advanced research, study, and teaching opportunities in over 140 countries.

Architecture Awards

American Institute of Architects Medal: Ian Miley (MArch I AP ’20)

The American Institute of Architects Medal is awarded to a professional degree student in the Master in Architecture graduating class who has achieved the highest level of excellence in overall scholarship throughout the course of their studies.

Alpha Rho Chi Medal: Milos Mladenovic (MArch I ’20)

The Alpha Rho Chi Medal, which is awarded to the graduating student who has achieved the best general record of leadership and service to the department, and who gives promise of professional merit through their character.

James Templeton Kelley Prize MArch I: Ian Miley (MArch I AP ’20) for “Stranger in Moscow: The Diplomatic Illusive

James Templeton Kelley Prize MArch II: Anna Goga (MArch II ’20) for “Porch House + 300 Panels, 400 Cuts, 400 Bandages”

The James Templeton Kelley Prize recognizes the best final design project submitted by a graduating student in the architecture degree programs.

Julia Amory Appleton Traveling Fellowship in Architecture: Radu-Remus Macovei (MArch I/MUP ’20)

The Julia Amory Appleton Traveling Fellowship is given to a student in the Department of Architecture on the basis of academic achievement as well as the worthiness of the project to be undertaken.

Kevin V. Kieran Prize: Nicolás Delgado Alcega (MArch II ’20)

Kevin V. Kieran Prize: Yotam Ben-Hur (MArch II ’20)

Kevin V. Kieran Prize: David Mitchell Kim (MArch II ’20)

The Kevin V. Kieran Prize recognizes the highest level of academic achievement among students graduating from the post-professional Master in Architecture program.

Dept. of Architecture Faculty Design Award MArch I: Euipoom Estelle Yoon (MArch I ’20)

Dept. of Architecture Faculty Design Award MArch II: Hee Young Pyun (MArch II ’20)

The Department of Architecture Faculty Design Award was established by the faculty of the Department of Architecture with the aim of recognizing significant achievement within a body of design work completed by a student at the GSD. This award is given to graduating students from each of the department’s two programs.

Landscape Architecture Awards

Thesis Prize in Landscape Architecture: Chelsea Kilburn (MLA I AP ’20) for “That Sinking Feeling: Subsidence Parables of the San Joaquin Valley“

The Landscape Architecture Thesis Prize is given to the graduating student who has prepared the best independent thesis during the past academic year.

2020 Landscape Architecture Foundation Olmsted Scholar: Nadyeli Quiroz (MDes/MLA I AP ’20)

Each year the faculty in the Department of Landscape Architecture nominates a student for the Landscape Architecture Foundation Olmsted Scholars Program. The program recognizes and supports students with exceptional leadership potential.

Norman T. Newton Prize: Siwen Xie (MLA I ’20)

The Norman T. Newton Prize is given to a graduating landscape architecture student whose work best exemplifies achievement in design expression as realized in any medium.

Pete Walker & Partners Fellowship for Landscape Architecture: Carson Fisk-Vittori (MLA I ’20)

Pete Walker & Partners Fellowship for Landscape Architecture: Danica Danielle Liongson (MDes Urbanism, Landscape, Ecology/MLA I 2020)

The Pete Walker and Partners Fellowship for Landscape Architecture is awarded to support travel and study for a graduating GSD student to advance their understanding of the body of scholarship and practices related to landscape design.

Jacob Weidenmann Prize: Jonathon Koewler (MLA I AP ’20)

The Jacob Weidenmann Prize is awarded to the student of the most distinguished design achievement graduating from the Department of Landscape Architecture.

ASLA Certificate of Merit: Michael Cafiero (MLA I AP ’20)

ASLA Certificate of Merit: Isaac W. Stein (MDes Risk & Resilience/MLA II ’20)

ASLA Certificate of Honor: Samuel Murdoch Gilbert (MLA I ’20)

Each year the faculty in the Department of Landscape Architecture nominates students for the American Society of Landscape Architecture Awards.

Charles Eliot Traveling Fellowship in Landscape Architecture: Andy Lee (MLA I AP/MUP ’20)

The Charles Eliot Traveling Fellowship is awarded annually as the highest honor by the Department of Landscape Architecture to one of its graduates.

Urban Planning and Design

Academic Excellence in Urban Planning: Amelia Muller (MUP ’20)

Academic Excellence in Urban Design: Soledad Patiño (MAUD ’20)

The Awards for Academic Excellence in Urban Planning and Urban Design honors graduating students from each of the programs who have achieved the highest academic record.

Award for Outstanding Leadership in Urban Planning: Emily McGovern Duma (MUP ’20)

Award for Outstanding Leadership in Urban Planning: Laura Greenberg (MAUD ’20)

The Award for Outstanding Leadership in Urban Planning and Urban Design honors graduating students from each of the programs who have demonstrated outstanding leadership during their time at the Graduate School of Design.

Urban Planning Thesis Prize: Margaret Haltom (MUP ’20) for “The Next Southern Landmark: A Roadmap to Confederate Monument Redesigns and RFP for the Site of a Former White Supremacist Statue“

Urban Design Thesis Prize: Justin Cawley (MAUD ’20), “Rescaling the University: Vertical Campuses and Postindustrial Urban Restructuring in Western Sydney“

The Department of Urban Planning and Design Thesis Prize is given to the graduating students in each of the programs who have prepared the best independent theses during the past academic year.

The Award for Excellence in Project-Based Urban Planning: Brett Alexander Merriam (MUP ’20)

The Award for Excellence in Project-Based Urban Planning is given to students who have demonstrated exceptional ability in urban planning projects including research and design studios throughout their course of study.

The Award for Excellence in Urban Design: Sarah Fayad (MLAUD ’20)

The Award for Excellence in Urban Design is given to students who have demonstrated exceptional design ability throughout their course of study in the Urban Design program.

AICP Outstanding Student Award: Juan Pablo Reynoso (MUP/MPP ’20)

The American Institute of Certified Planners Outstanding Student Award recognizes outstanding attainment in the study of planning by students graduating from accredited planning programs. The recipient of the award is chosen by a jury of planning faculty at each school.

Ferdinand Colloredo-Mansfeld Prize for Superior Achievement in Real Estate Studies: Patrick Braga (MUP ’20)

Ferdinand Colloredo-Mansfeld Prize for Superior Achievement in Real Estate Studies: Adriel Deller (MDes Real Estate & the Built Environment ’20)

The Ferdinand Colloredo-Mansfeld Prize for Superior Achievement in Real Estate Studies is awarded annually to a graduating student from any program who has exhibited superior academic accomplishment and leadership in real estate studies.

Druker Traveling Fellowship: Laura Greenberg (MAUD ’20) to study study Eco-Districts in the United States

Established in 1986, The Druker Traveling Fellowship is open to all students at the GSD who demonstrate excellence in the design of urban environments. It offers students the opportunity to travel in the United States or abroad to pursue study that advances understanding of urban design.

Design Studies

Dimitris Pikionis Award: Wilfred Guerron (MDes HPDM ’20)

The Dimitris Pikionis Award recognizes a student for outstanding academic performance in the Master in Design Studies degree program.

The Daniel L. Schodek Award for Technology and Sustainability: Xinzhu Chen (MDes Energy & Environments ’20)

The Daniel L. Schodek Award for Technology and Sustainability honors the memory and legacy of Professor Daniel Schodek and the standards of excellence he established during his 40 years of teaching and mentoring at the GSD. The award is given annually in recognition of the best Master in Design Studies thesis in the area of technology and sustainable design.

The Design Studies Thesis Prize: Angela Mayrina (MDes Art, Design & Public Domain) for “A Guidebook to an Empty Land: Kalimantan and the Shadows of the Capital“

The Design Studies Thesis Prize: Karan Saharya (MDes Critical Conservation ’20) for “In the Name of Heritage: Conservation as an Agent of Differential Development, Spatial Cleansing, and Social Exclusion in Mehrauli, Delhi“

The Design Studies Thesis Prize is given annually for the best thesis by a Master in Design Studies student.

Design Engineering

Overall Academic Performance: Mengxi Tan (MDE ’20)

The Overall Academic Performance award recognizes a graduating MDE student for outstanding academic performance in the Master in Design Engineering degree program.

Leadership and Community: Taylor Greenberg Goldy (MDE ’20)

Leadership and Community: Mia Zaidan (MDE ’20)

The Leadership and Community prize recognizes a graduating student who has displayed outstanding leadership and community building within the Design Engineering cohort and representation of MDE values to the larger world.

Outstanding Independent Design Engineering Project: Jacob Schonberger (MDE ’20) and Mengxi Tan (MDE ’20)

The Outstanding Design Engineering Project award honors one or more graduating MDE students who have presented the Design Engineering Project that contributes, in the most compelling way, to understanding and addressing a complex societal problem.

How can design improve disease modeling and outbreak response? A simulation tool by GSD alum Michael de St. Aubin offers answers

The global COVID-19 pandemic has placed roughly one-third of the human population on some form of lockdown. But with spring in full swing, economies in free fall, and infections on the decline in early hotspots, many are antsy to get back to work, school, and life as we once knew it. Health experts, citing disease models, warn that easing restrictions too soon could cause the virus to flare up again. The silver bullet of a coronavirus vaccine is still at least a year out, which means the burden of containing the epidemic continues to fall on the public, who must sustain distancing behaviors even as it costs us our jobs, social lives, and everyday routines. But when the worst appears to be behind us and we’re finally descending the other side of the curve, how will we convince billions of people, blinded by the light at the end of the tunnel, to keep cooperating until COVID-19 is gone for good?

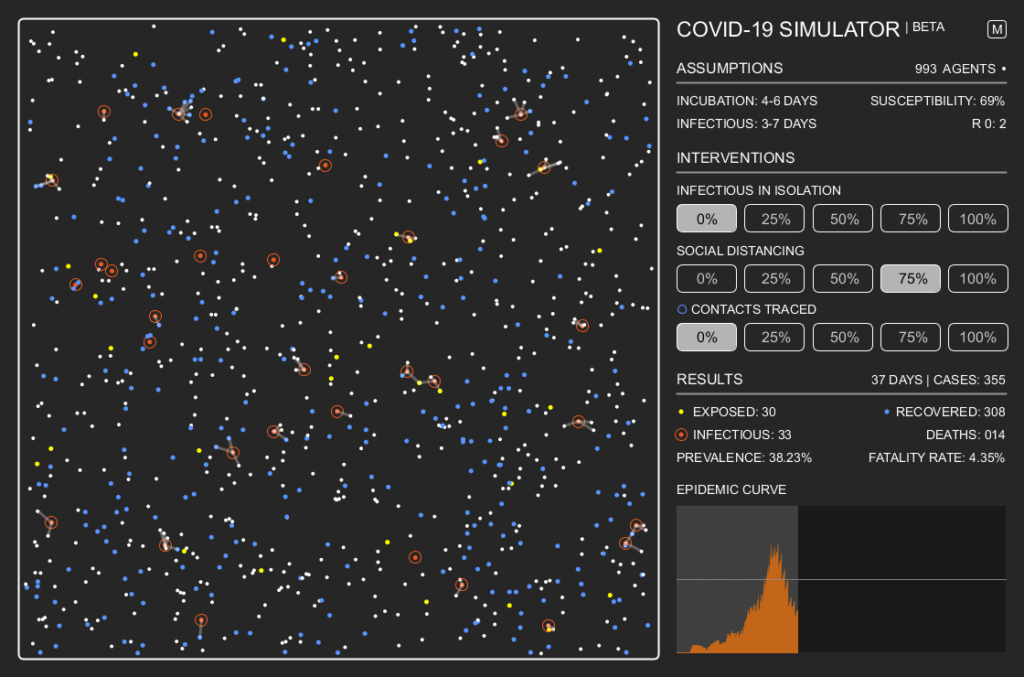

Harvard Graduate School of Design alum Michael de St. Aubin thinks better-designed disease models can have a greater impact on the public, as well as on healthcare and policy decision-makers, by helping us to see just how much our actions matter during the midst of an epidemic and after we’ve flattened the curve. Combining the sophisticated mathematical formulas of an epidemiological model with the look and feel of a computer game, his Visual Response Simulator , or ViRS, is a web-based visualization tool that’s designed with non-experts in mind. “The [visualization of inputs and outputs of] models used by health professionals or referenced by media outlets come from academic institutions—they’re set up for people with a background in epidemiology, and they’re kind of archaic,” notes de St. Aubin, an architect by training. “ViRS brings these ideas up to speed with modern interaction and visualization. It makes disease modeling more accessible to a wider audience by making it as easy as possible to understand.”

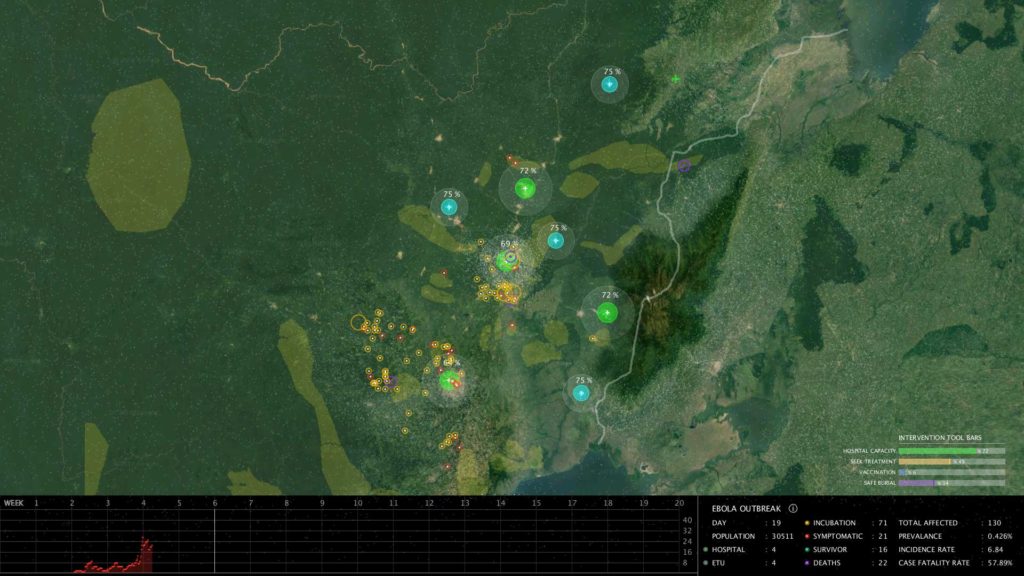

De St. Aubin plans to partner with video game designers to create ViRS’s interactive interface. The platform is specifically designed so people can test the impact of different outbreak response strategies (such as vaccination, public education, or mobile health facilities) from the moment they are implemented, and quickly see what happens when these interventions are scaled up or down. Traditional disease models, by contrast, demand any response tactics be determined at the outset, and require dozens of epidemic simulations run to their completion before returning the mean results. “I’ve built ViRS so the user can control and change their strategy mid-simulation run,” de St. Aubin points out. “It gives you the interaction to manipulate it in real time and visualizes all of those effects so it’s easy to see what’s working.”

Also unique is the integration of satellite imagery and geo-spatial data, which factors in population density, transportation networks, and existing hospital facilities in a given location. ViRS’s on-screen simulation provides a bird’s-eye view as a population of autonomous agents is ravaged by disease in accelerated time. Toolbars allow for toggling intervention variables, while counters track the total number of exposures, infections, and deaths. As the disease progresses, a now-familiar epidemic curve plots out the levels of infection over time, with spikes and dips appearing where interventions were imposed or lifted.

De St. Aubin began developing ViRS in 2017 as a graduate student in the Risk and Resilience concentration in the Masters in Design Studies program. Originally designed to model data from Ebola outbreaks in Western Africa, the simulator can be tailored to the characteristics of any disease, real or hypothetical. While in quarantine over the past several weeks, de St. Aubin adapted ViRS to create a basic interactive simulation for the current COVID-19 pandemic, using scientific research on the disease’s dynamics. “Right now, a lot of people are interested in epidemiology models and how they’re used. This particular model is for public engagement and knowledge sharing,” he says. The COVID-19 simulation lets users see for themselves how adhering to social distancing and self-isolation guidelines can dramatically flatten the curve of the outbreak, and more critically, what might happen if such restrictions are lifted in the crucial months ahead.

In this simulation, the hapless agents are rendered as dots moving around inside an empty box, bumping into and infecting one another with increasing speed as the disease permeates the population. But with one click, users can enact social distancing measures that immobilize 25 percent, 50 percent, 75 percent, or 100 percent of the dots and send the infection curve plummeting. Remove the intervention tactics and infection rates resume their climb once more. “It’s a simple tool people can interact with and learn from, and it demonstrates why these non-clinical public health interventions are so important,” says de St. Aubin.

Since graduating in 2018, de St. Aubin has been working with the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative and continuing to refine ViRS to model response strategies for combating Ebola. (With another team at the H.H.I., he has also developed a global COVID-19 perceptions, knowledge, and behaviors survey , and a dashboard for visualizing and filtering survey data.) While ViRS is not yet validated for official use, de St. Aubin already foresees how the platform could bring value to a number of different applications.

Primarily, he envisions ViRS as a tool to get the public to learn about, support, and adhere to health guidelines. “The interaction and the visual qualities make it much easier to convince people how—if these intervention strategies are followed and to what degree—the outbreak can be contained and come to a stop,” he says. Its multiple-scenario, game-like properties, and graphic interface also make ViRS an ideal tool for epidemiology and outbreak training and education. Further, when used operationally in the field, the simulator could rapidly test response tactics and inform contingency plans, while making data easy to visualize and share for coordinating response efforts across teams.

De St. Aubin first became interested in public health and epidemiology in 2015, while working as an architect in Boston. Traveling to Ebola-stricken regions of Africa to do hospital facility assessments, he saw outbreak response in action. “There was a huge lack of designers in this profession and not a lot of design thinking, or design sensibilities,” he recalls. “I felt like I could fill a gap. I went to school thinking, ‘How can I increase my value as a designer and integrate myself into this field full-time?’”

At the GSD, de St. Aubin found the Risk and Resilience concentration a natural fit with its commitment to countering social and political issues through design. There, he took a step away from architecture, pursuing research in mapping, technology, and humanitarian response, augmented with classwork at the Harvard School of Public Health and a data visualization course at MIT. Although he was the only student in his cohort focused on infectious disease modeling, de St. Aubin predicts the growing threat of global pandemics will inspire more designers to become interested in this area. “If designers are really serious about making a difference, we can’t continue to operate in a vacuum,” he says. “We need to integrate ourselves with the fields and organizations that are doing the work directly and leading the charge, working with different UN agencies, different international organizations, and local NGOs as well.”

COVID-19 has spurred architects and designers around the world into action; they’re creating open-source files for 3-D printing respirator valves and face shields, translating the UN’s critical health messages into impactful graphics, and designing temporary coronavirus testing facilities . This unprecedented global pandemic has taught us that design can play a crucial role in better preparing us for the challenges and opportunities presented by future outbreaks, and that our individual actions and contributions can make a huge difference for the welfare of the greater good.

“Designers can get involved in so many ways, not just disease modeling, but also planning—coming up with policies and guidelines for our urban spaces to be more adaptive to these sorts of things. Rethinking how people are going to be living in the future so it’s not a total shock to our communities and our economy when everyone is forced to stay at home,” says de St. Aubin. “Our creativity and ability to forward-think is going to be really useful. There’s going to be so much need and focus on that for better resiliency in the future.”

Diane Davis on the GSD’s Risk and Resilience track

In these tough times, when dystopian fears loom large and the design professions are scrambling to find new ways of addressing the COVID-19 global crisis, it is worth reflecting on the history of the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s efforts to offer a programmatic venue for students and faculty to address extreme vulnerabilities in the built environment. The recent global health pandemic may be the latest such crisis, but it is far from the first. We at the GSD have been strengthening our focus on similarly catastrophic events through the Risk and Resilience track of the Master in Design Studies program.

Over the last several years, students who joined our cohort have been addressing built environmental and design challenges related to climate change, health and environmental crises, warfare, and other “natural” or man-made disasters that disrupt systems, societies, and the lives of everyday people. We can only assume that student interest in similarly pressing matters will continue to rise, not just in response to the current pandemic, but also as all humankind faces a world where certainty, stability, and progress are no longer a given. In light of these challenges, we want to share the intellectual and programmatic journey that led to the development of the Risk and Resilience track at the GSD.

Whether conceived in terms of ‘bouncing back to normal’ after a disaster, or as a means of reestablishing system equilibrium after a shock, embracing resilience can be translated as having faith that with enough attention and adaptive effort, the future can be better.

When I came to Harvard in 2012, the Master in Design Studies program offered a variety of specializations for students, one of which was called “Anticipatory Spatial Practices.” The track already had a small cohort of students enrolled. I wondered what exactly they thought they would be doing in a program with such a title. The moniker seemed pretentious at best, and incomprehensible at worst. I also was of the opinion that everything about the planning and design professions necessarily requires or embodies some form of anticipatory spatial practice. If a program that set as its conceptual ambition a desire to engage the fundamental telos of the design disciplines in their entirety, could it be specific enough to generate something novel? I quickly learned from students that their ambitions were actually quite grounded, and that they found this track an invitation to focus on some of the most important challenges of our times.

The vast majority of our students were—and still are—interested in climate change and environmental sustainability, having understood that rapid urbanization of the built environment had spatially transformed our cities, landscapes, and the globe in ways that were undermining our collective capacities to remain healthy as a species and a planet. In that sense, the title of the track offered an opportunity to think about what could or should be different in terms of spatial practices to push back against these problems. Yet I also noted that a few of our enrolled students had come to the GSD from the world of war, so to speak, having worked in refugee camps or combat situations where both the threat and reality of violence produced its own form of crisis, ranging from forced displacement to death. These students, like the climate and environmental activists, recognized a clear need for spatial preemption of the most egregious losses and vulnerabilities associated with traumatic, violent events. The intersection of these sets of challenges drew me to the track, which I subsequently agreed to co-direct, starting in 2014.

What most captured my imagination were the parallels that thread through the various problems under study. Despite what looked like very different subjects, there seemed to be some common questions that concerned students interested both in the environmental crisis and the refugee crisis. It was not just that students focusing on these distinct topics were concerned with issues of displacement; it also appeared that common languages were emerging across the disparate problem areas. Two of the most obvious terms were “resilience” and “risk.” In recognition of a potentially unifying discourse, the program leadership agreed to shift the track’s title, and used this shift to both craft and reflect new pedagogical aims.

While students would continue to think projectively about alternative futures and how to construct them (i.e., anticipatory spatial practices), they would also be charged with transcending disciplinary and problem-area silos in the study of vulnerabilities. This pedagogy encouraged students interested in environmental crises or climate change to learn from students interested in war and vice versa, as they entered a program asking them to find parallels in these two “battlefields” of action. It also gave them an opportunity to reflect on the languages, theories, and design practices commonly deployed in each of these seemingly incongruent problem areas, and innovate new actionable framings through this cross-fertilization.

With this mandate in mind, in 2014 we formally changed the track’s title to “Risk and Resilience,” and never looked back. We have encouraged students to ask whether the concepts, practices, and assumptions about scales of agency common among those addressing one form of crisis can be applied to another. For example, if scholars addressing the climate crisis deployed approaches that echo those concerned with war, forced displacement, and other risks experienced by victims of ongoing violence, would new possibilities for action emerge? In light of COVID-19, which has been described through languages of warfare—with the virus seen as a stealth enemy that knows no territorial boundaries and that can leave a trail of damage and death in its wake—this decision now seems prescient.

Our mission statement, crafted in 2015 and posted on our web page, was the following:

The world faces unpredictable challenges at increasing intensities—natural disasters, ecological uncertainty, public health crises, extreme social inequity, rising violence—and yet counters and absorbs risk through acts of resilience. Risk & Resilience, a concentration area within the Master in Design Studies, sets out to support novelapproaches to socio–spatial planning through design. Design as a discipline provides cities, communities, and individuals with tools to effectively prepare for, cope with, and anticipate rapid change within the spatial, social and economic vulnerabilities it produces. The program prepares students to identify, articulate and propose preemptive forms of socio-spatial and territorial practice. While the program is grounded in the physical and tectonic realities of location, social and political conflicts over risk and resilience are just as likely to emerge and serve as sites of investigation (1).

As we face the global virus pandemic, our mission appears ever more important. With our skill sets as designers and planners marshalled in the service of identifying novel ways to confront this newest crisis, we can learn from some of the pedagogical challenges rippling through the track as it has evolved over the years. One is the importance of prioritizing the concept of risk, perhaps even over resilience, as we confront unknown futures that will undoubtedly present continual new threats, including those not yet anticipated.

When we launched the new track title in 2014, the notion of “resilience” was taking the policy, design, and urban planning worlds by storm. It defined the Rockefeller Foundation’s global initiative, 100 Resilient Cities, and the language of resilience appeared in a barrage of academic conferences and study centers hosted by universities and multilaterals. It also came to define new programs sponsored by technology corporations and design firms (including the joint IBM-AECOM piloting of a disaster resilience scorecard), and was even featured in the US State Department’s appropriation of resilience as a thematic rationale for international aid. The latter was built around the understanding that environmental vulnerabilities, broadly defined, are inextricably linked to problems of poverty, conflict, and violence. With the benefit of hindsight, we can now also add climate change to the list of factors that lead to migration and warfare.

The point is that when we renamed the track, the notion of resilience was being promoted as the basis for a new and expanding repertoire of tools—from novel technologies to reconfigured mapping and building products—that would guide us to a secure urban and global future. But focusing on resilience, which is frequently defined as the ability to cope and adapt so that individuals or communities survive and thrive, often meant avoiding the hard questions of power, inequality, and the ways that limited resources forced people to fend for themselves.

Whether conceived in terms of “bouncing back to normal” after a disaster, or as a means of reestablishing system equilibrium after a shock, embracing resilience can be translated as having faith that with enough attention and adaptive effort, the future can be better. But as we fall headlong into a state of irreversible environmental damage to the planet, and as some experts are suggesting that the coronavirus may be with us to stay, longstanding faith in this concept may seem a bit naive. After all, the future is still so clearly unknown, and the long-term damages that COVID-19 will produce in the health of individuals, the health of cities, and the health of economies has yet to be fully understood.

From the moment we inaugurated the new track title at the GSD, we understood that “resilience” is a tricky word, readily veering into the ideological. Some scholars have criticized this concept as offering an excuse to let citizens cope on their own while the government and the market continue to aid each other (2). Others argue that a return to normalcy is what we must avoid, because “normalcy” is often what produces crisis in the first place (3). Such an argument is frequently made in discussions of climate change and environmental crisis, which leads to deliberations about how normal it is to have built cities and societies around infrastructures and forms of resource extraction that contribute to skyrocketing carbon emissions.

From the vantage point of MDes, however, our greatest concern was that a focus on resilience might become an invitation to ignore risk, and lead us to ignore the inter-relationalities of risk that may constrain resilience. For precisely this reason, the track defines itself as engaged with concepts of both risk and resilience, and their relationships to each other (4). Our students have been encouraged to examine the trade-offs among forms and patterns of risk and resilience: not just among different residents or locations in the same city, but also in terms of immediate versus long-term gains in livability, such that coping strategies in some domains (say environment) may actually reinforce the structural problems that create risks in other domains (say inequality). To the extent that urban, social, economic, and environmental ecologies are interconnected—both locally and across territories that link cities to regions and beyond—any resilience strategy must be grounded in an appreciation of the entire landscape of a city and its properties as a system embedded in a larger ecology.

So the GSD does not aim to jettison a concern with resilience, but rather, to situate it in territorial scales while also interrogating and reconceptualizing its utility as a concept. One way to do so is to disaggregate adaptation strategies, and understand when adaptive responses to vulnerabilities or crises will establish a pathway toward a better future. Stated differently, under what conditions will adaptations—whether voluntarily undertaken by citizens, mandated by governing authorities, or crafted by planners and designers—diminish rather than increase vulnerability, and perhaps even remain effective in transforming overall vulnerabilities?

In my own work on urban violence, I have proposed that we think more carefully about positive, negative, and equilibrium resilience as three possible outcomes, with an understanding of how strategic and tactical actions may be reformulated by political, social, and economic structures to produce negative instead of positive pathways out of crisis (5). For anyone interested in the relationship between risk and resilience, or in designing new strategies to address vulnerability, the focus must be as much on the context in which adaptations are proposed as on the mechanics or design of the adaptation itself. Design thinking or design and planning action must start from an understanding of this complexity, and with the acknowledgement that any single project or policy intervention will have implications far beyond its targeted scope, both in scalar and sectoral terms.

To enable constructive action in the context of multiplying and interconnected vulnerabilities that unfold at the local and the global scale, we thus return to the idea of risk. In the MDes track, our students build, design, and plan for risk rather than just resilience. They are creating new guiding principles and paradigms in the process. In the heyday of modernism, many professional designers, architects, and planners found inspiration in dreams of order; their commitment was founded on the belief that tensions between the natural and the built and social environment could be managed if not overcome. When modernist paradigms ruled, the tendency to build better reinforced faith in the inevitability of progress, and in the belief that any new urban or built environmental challenge could be resolved if enough technology, money, and creativity were thrown at it.

Now, in the midst of a global pandemic and at a time of accelerating risks, such assumptions are the subject of interrogation. We continue to train our students to be up to the task of facing the 21st century and imagining how it should be if risk is to be contained or reduced. This requires all of us to recognize that many of the strategies associated with the modernist agenda have created insurmountable problems for us today. Some argue that the COVID-19 pandemic is a consequence of our systematic destruction of the natural world in order to acquire territories and material resources—and that by devastating animal habitats we hastened the spread of viruses between animals and humans. Others highlight the impacts of intensifying economic globalization on the flow of goods, people, and yes, viruses, that accompany capital as it moves around the world. At this point it may be too late to turn back the clock on the damages already wrought and the terrors already unleashed; but we do not have the luxury of ignoring where we could and should be heading.

This is the mandate of the Risk and Resilience track and the committed students who join this program: to embrace a mission to address some of the most fundamental risks of our times. In addition to considering new building and design techniques, they are thinking more purposefully about the form and connectivity of cities, which are conceived as sites that host intra-urban spatial inequalities but that are also networked to their rural hinterlands, their nations, and the globe. Doing so is of great urgency now, particularly because the isolation and quarantine strategies recommended by health professionals are challenging the social and spatial connectivity aims that have inspired innovation in the urban design discipline, even as they are unmasking new inequalities in living standards and neighborhoods among the city’s most and least privileged populations. There is also the looming question of food insecurity, given disruptions in connectivity between cities and the countryside (6). Landscape architects will need to join with urban planners and designers to reestablish those interrupted networks.

Each one of these sectoral challenges will place the onus on our students to learn how to identify, map, and communicate urban, health, and environmental risks or vulnerabilities in ways that are legible to citizens and city-builders. Through open engagement with citizens themselves, and building on our own local knowledge, we can identify the design and building practices that use the future as a reference point for building better cities today.

Finally, and in addition to the huge commitment to enabling a robust urbanism that makes sense in the context of future ecologies, the pandemic may also force all of us to value and embrace flexibility as a concept in the design of buildings, land uses, and urban infrastructure. This will be a departure from the modernist toolkit of the past. Yet as we move forward, the design disciplines may need to embrace the benefits of informality over formality, if only to allow for dynamism rather than fixity in city form and function.

To be sure, even this unconventional framing of future design action implies a belief in the possibility of conquering risk in ways that may too readily echo modernist sensibilities. To push back against this, it is important to recognize that the notion of risk can be appropriated ideologically, just as has happened with resilience. The stark truth is that risk does not reside only in the domain of science and the “factual.” Risk as a phenomenon or a legible concern is informed by power and social questions, including who has the right or authority to define risk, how risk is distributed, and who pays and who gains from it. In that sense, it is important to avoid the “tyranny of risk” as a defining principle for action, and to understand that discourses of risk can be abused to justify displacement, controls on citizens, limits on space, and other forms of exclusion that challenge the social and equity principles that also frequently guide our work (7).

I close on a note of optimism. The emergence of new risks holds the potential to create new disciplinary synergies and to bring a wide range of experts together to jointly address the multiple vulnerabilities embedded in building typologies, contemporary lifestyles, cityscapes, and the expanding territorial landscapes in which they are all embedded. Universities have long been trying to keep up with the pace of the enormous changes common to what Ulrich Beck called our “global risk society,” but like all institutions they are slow to change (8). At the GSD, we’ve been able to modify and recast our concentration tracks to keep up with and adapt to some of the major developments of our times. The relatively recent “birth” of the Risk and Resilience track, and its ongoing evolution as it prepares students to confront emerging challenges, shows that this is possible in programmatic terms at least.

To stay abreast of our unfolding reality will require continued interdisciplinary interaction and dialogue among the various design, planning, and architectural professionals, along with allies in the social sciences, biological, engineering, technology, and public health professions. Although collaboration has always been central to design practices, the range of risks we face today means we need even more disciplinary partners, beyond the building sciences and the familiar domains of urbanism. The GSD is well-positioned to champion such a mission, and we believe that Risk and Resilience students will be leaders in this ambitious and vital endeavor.

Diane E. Davis is the Charles Dyer Norton Professor of Regional Planning and Urbanism, former Chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design, and Area Head of MDes in Risk and Resilience at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.

(1) At the time, I co-directed the track with Rosetta Elkin, professor of Landscape Architecture, and since then we have sought to insure that faculty co-heads span the disciplinary silos of the GSD. The faculty most involved in the track over the last several years are Dilip da Cunha and Abby Spinak.

(2) For example, Kaika (2017) has presented a helpful critique of the notion of resilience, especially as it pertains to the context of urban planning.

(3) See: Latour (2020) and Lorenzini (2020).

(4) I have treated the relationship between the concepts of risk and resilience as they apply to urban design and planning practices in Davis (2015).

(5) See: Davis (2012).

(6) For an historical account of the rise of urban food insecurity and its impact on western forms of governance, see: Foucault (2007), 32ff.

(7) For examinations of the concept of risk and its centrality in modernist ways of thinking, see: Beck (1992) and Giddens (2002).

(8) See also: Beck (1992).

Bibliography

Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Translated by Mark Ritter. London: Sage Publications.

Davis, Diane E. 2012. Urban Resilience in Situations of Chronic Violence. MIT Center for International Studies/USAID, 134 pp.

“From Risk to Resilience and Back: New Design Assemblages for Confronting Unknown Future.” Topos, Garten + Landschaft, June 2015: 57-59.

Foucault, Michel. 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977-1978. Ed. Michel Senellart, trans. Graham Burchell. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Giddens, Anthony. 2002. Runaway World. New York: Routledge.

Kaika, Maria. 2017. “‘Don’t Call Me Resilient Again!’: The New Urban Agenda as Immunology … or … What Happens When Communities Refuse to Be Vaccinated with ‘Smart Cities’ and Indicators.” Environment and Urbanization 29, no. 1 (April 2017): 89–102.

Latour, Bruno. 2020. “What Protective Measures Can You Think of so We Don’t Go Back to the Pre-Crisis Production Model?” Translated by Stephen Muecke. Versopolis Review, April 7, 2020.

Lorenzini, Daniele. 2020. “Biopolitics in the Time of Coronavirus.” In the Moment (Critical Inquiry), April 2, 2020.

Bing Wang on COVID-19’s impact on the real estate sector

The crisis brought about by the coronavirus has utterly paralyzed the normal functioning of society on a global scale. It has intensified underlying social, economic, and political tensions and has accelerated preexisting trends. The fragility of the public health infrastructure in many countries around the world has become evident.

Going forward, we don’t know whether the coronavirus will be successfully contained by a new vaccine in 2021. For the US, the Federal Reserve’s unique position in providing liquidity—both domestically and beyond its borders—means that it will play a crucial role in managing the economic distress resulting from the crisis. The Fed’s leadership, together with the fact that US Treasuries are still considered a safe harbor for risk-averse investors, will likely safeguard the US economy, the largest in the world.

It is critical to leverage this crisis as an opportunity to pursue a development and investment model that is more equitable and just.

on the need for recovery planning that does not rely solely on modern techniques of finance in the name of “market efficiency.”

For China—the second largest economy—as life gradually returns to normal in many cities, the critical test will be its trajectory of economic recovery. Local governments’ and state-owned enterprises’ mounting debt is likely the most onerous burden for its stability. At the same time, China’s focus on the expansion of its public health infrastructure, domestic consumption, and the acceleration of development in less developed areas of the country holds promise for the economy.

Within these two macro environments, there are profound implications for the real estate sector. The most evident effect of COVID-19 is the abrupt halt of real estate transactions as investors move into a wait-and-see mode, with delayed investment decisions and pending financing possibilities.

In the longer term, as the pandemic forces us to recognize that our physical built environment is ill-prepared for emergencies, certain building typologies will undergo intense review and adjustments in design, construction, and operation. Relatively speaking, multifamily residential and logistical assets have been exposed to lower operational and financial risks during the pandemic, and have performed better in the capital markets; they will continue to be preferred asset classes.

Hospitality and retail real estate, where services drive growth, have faced unprecedented challenges, with many smaller retailers and hotels struggling to survive. Similarly, for the office asset class, we expect transitory downward pressure in the near term. Investors and users will scrutinize the pre-crisis emphasis on densified communal environments—including, for example, the co-working office typology that emerged from the 2007–2009 recession.

In addition, physical flexibility and adaptability of buildings and spaces will be highlighted in the long run as a necessity for investors; the market will assign increased value to resilience in times of crisis and as an insurance against operational risks. Digitalization (which refers to digital connectivity provided by broadband internet) and data analytics (associated with artificial intelligence provided by digital infrastructure), need to be considered at various physical scales. At the building scale, digitalization is essential to connect individual households and to enable working from home and long-distance collaboration. At the urban scale, digitalization is vital so governments can rely on data to assess, forecast, and manage the current coronavirus along with other potential emergencies in the future.

Public health infrastructure will become a critical component of master urban planning and will provide flexibility in the configuration, design, and function planning of public open spaces in cities. In that sense, public health–related services will likely rise in importance to investors, and perhaps become a fourth component of what is currently known as “ESG” considerations—for Environment, Social Responsibility, and Governance. As the crisis has laid bare the inequities and injustices that threaten people’s well-being, safety, and lives, especially in the US, the momentum that began to emerge before the pandemic is expected to continue.

It is critical to leverage this crisis as an opportunity—to pursue a development and investment model that is more equitable and just. Questions that need to be considered by both private and public sectors include: How to encourage investments that focus on the affordability of real estate and shared public benefits; how to establish policies and programs that bolster housing infrastructure and capacity to effectively deliver assistance to vulnerable renters; and how to incentivize funding to improve public health and well-being. We must address and seek solutions to these issues without relying solely on modern techniques of finance in the name of “market efficiency.”

Historical pandemics have structurally reshaped how we as a society conceived of and conceptualized cities, urban developments, and collective well-being. There is no reason to think that this pandemic will not do the same.

Bing Wang is associate professor at the GSD and a faculty area head for the Real Estate and the Built Environment concentration of the Master in Design Studies. She is the faculty co-chair for the Real Estate Management Program, a joint executive program between the GSD and Harvard Business School, and co-chair of the Advanced Real Estate Development Program at the GSD. She is on the steering committee of the Harvard China Fund and an elected board director of the American Real Estate Society.

Tobias Just is professor for real estate at the University of Regensburg and academic director of the IREBS Real Estate Academy. He is president of the German Society of Property Researchers, editor of the ZIÖ—the German Journal of Real Estate Research, and served on the management board of ULI Germany between 2012 and 2018. In 2017, Just became Fellow of the RICS by nomination.

Stephen F. Gray: “We have a name for the uneven distribution of exposure and risk along racial lines, and it’s not COVID-19. It’s structural racism.”

COVID-19 is a dangerous new reality, spreading indiscriminately and without regard for skin color or cultural background. Yet many black and brown Americans are dying at disproportionately high rates. Will this be the time that we stop talking about structural racism and finally do something about it?

By all accounts of science and chance—and with equal levels of exposure and risk—the rates of infection and death across all communities should be the same. But as we have learned from responsible news reporting, the rates of infection and death are not the same, particularly along racial lines. As our country surpasses 1.3 million infections and more than 80,000 deaths, Black people so far represent 30 percent of all infections yet only 13 percent of the national population. In some cities, the number is even higher . However, we should not be surprised.

Where this coronavirus is lacking in racial bias, the United States has made up for with a resilient and highly adaptive white supremacist capitalist racial ideology. It is an ideology that is etched into our national DNA, rooted in the exploitation of human beings for economic gain—the perverse logic of slavery—and which has laid a long and injurious legacy for black and brown communities.

n the willingness of US leaders to accept collateral damage in exchange for capital gain—at the expense of black and brown communities

For communities of color in the United States, COVID-19 has transformed an otherwise protracted assortment of chronic health issues associated with poverty, overcrowding, and uneven access to public space or quality housing—among them cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, and asthma—turning them into abrupt and immediate death sentences. We have a name for the uneven distribution of exposure and risk along racial lines, and it’s not COVID-19. It’s structural racism.

Where this coronavirus is lacking in racial bias, the United States has made up for with a resilient and highly adaptive white supremacist capitalist racial ideology. It is an ideology that is etched into our national DNA, rooted in the exploitation of human beings for economic gain—the perverse logic of slavery—and which has laid a long and injurious legacy for black and brown communities. It has justified spatial and economic exclusion (segregation and red lining), racial terrorism (Jim Crow laws and community massacres), community theft (block-busting and predatory lending), targeted community removal (urban renewal and federal highway programs), criminalization of blackness and loss of voting rights and citizenship (mass incarceration and deportation), or simply blanket ethnic exclusion (anti-immigration orders against what our President has named “shithole” countries).

As if all of that was not enough, communities who experience higher levels of exposure and risk to the coronavirus have now become our “essential workers,” positioned at the front lines of this pandemic. They are the transit workers, doormen, janitors, health care workers, food producers, grocery store staffers, and warehouse and delivery workers—those on which every one of us is relying to get us through this crisis. They are underpaid, underinsured, and they are very often black or brown.

Our nation’s willingness to accept collateral damage in exchange for capital gain is proven; especially during national disasters like the one we are experiencing now. As was the case for Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, and the poisoned water crisis in Flint when black and brown people were disproportionately affected, a national discussion about race is once again underway. But promising as these race-facing (and racism-naming) national discussions can seem while they are taking place, they always turn out to be fleeting. If action is taken at all, it relies on a ‘rising tides lift all boats’ framing rather than an explicit commitment to racial justice.

Though the COVID crisis has put the lethal legacy of slavery on full display, the CDC only recently started collecting and disaggregating data by race. Their slowness to act decisively is either from political embarrassment, willful ignorance, or ambivalence to the immediate and life-saving significance of this information, and so when the US President and many in his political party push to reopen the economy prematurely, we shouldn’t be surprised. Once again, economic concerns in this country are taking priority over public health concerns and human life, as they often do when black and brown people are involved. A more strategic rollout of this information could have allowed Americans to get on board with a strategy, supported by race-disaggregated data, to ensure that resources were directed to the right communities.

Structural racism is insidious. It doesn’t rely on decision-makers to themselves be racists. Instead, it is a generations-old system of norms and parameters which provide the framework for almost every decision we make. As history confirms, the roots of American society lie in a slave economy, and our racially-structured political and economic system is reinforced by a legal system that relies on history (which is precedent) for administering justice. In most cases, instead of radical transformation, our system delivers us a watered-down version of what we already are; in other words, when the gavel drops or the bill is passed, we are simply left with white-supremacist capitalist racial ideology-light. So, it should come as no surprise that racial equity transformation is slow, and that it never comes without a fight.

When you water something down, it becomes a diluted version of itself. What we need right now is something altogether different. Instead of passing up yet another opportunity to right a four-century-old wrong, it’s time to finally ensure that a post-COVID-19 recovery benefits both sides of the color-line and that we as a nation truly begin to address the structural roots of racial inequality. So, what is the organizing work, political work, and accountability work that needs to happen in order to ensure that the public good serves all of us equally? In many cases, tools for advancing racial equity already exist. Some can be hacked while others will need to be completely reimagined. But here’s where we can start:

Economic Development

- Race-equity criteria for Federal disaster grants targeting black and brown communities who are experiencing higher rates of infection and death from COVID-19 to support post-pandemic minority-owned business development, affordable housing subsidy, and home-owner stabilization programs.

- Targeted Investment in “shovel-ready” infrastructure projects in black and brown communities and as a way to reverse the legacies of infrastructural harm (ie.mid-century urban renewal and federal highway expansion programs).

- Experiential learning and on-the-job training with apprenticeships, pre-apprenticeships, and workforce incubation programs that connect black and brown communities to large-scale, long-term infrastructure projects .

- Connecting minority-owned businesses to unions to address labor shortages, changing industry, entry-level jobs through targeted training programs, and green jobs pipelines, and ensure that reliable employment pipelines typically accessible to unions also include people of color.

- Public-private partnerships with local Community Development Corporations (CDCs) so that locally-based minority developers have primary access to develop on public land in all neighborhoods, especially in majority-minority neighborhoods. Including cooperative-ownership models with cooperative community governance can further balance economic development interests with community-building objectives and creates a cycle of local reinvestment in communities.

Housing

- Public sector purchase of rental housing in all new developments to support the lowest income families in every neighborhood and increase the stock of publicly-administered affordable housing for black and brown families.

- Tax Increment Finance (TIF) district overlays for affordable housing in low-income neighborhoods that can be triggered to avoid displacement during early gentrification by capturing rising property tax revenue internally for affordable housing.

- Auxiliary Dwelling Unit (ADU) subsidies in black and brown communities to create income opportunities for homeowners while increasing their property values, and growing the availability of affordable rental housing for very low-income families.

The Public Domain

- Race-equity criteria for Federal disaster grants targeting black and brown communities with limited access to quality public space during COVID-19 to advance parks and open space improvements that support long-term public health and well-being.

- Multimodal transit and bicycle hubs to increase mobility options in areas with limited access to vehicles to increase healthy and affordable transportation options such as shaded sidewalks and protected bikeways.

- Streetscape improvement requirements for all new developments in communities of color to improve walking experiences for residents as well as making local job and retail centers more attractive.

- Mapping the digital divide by tracing current fiber optic infrastructure investments across cities and then adjustment plans to prioritize communities of color so that they have improved access to a post-COVID digital world.

- Community Mapping projects with communities of color so that they become the leaders in local decision-making about new developments and neighborhood improvements.

For communities of color, a cure for the harm caused by COVID-19 needs to go far beyond developing a vaccine. We also need social and economic policies that take on the underlying, longstanding, and persistent problems of structural racism.

Reflecting on this country’s long history of intentional racist planning and policy-making, today’s planners, designers, and policy-makers have an ethical obligation to realign our priorities and adopt intentional antiracist agendas that address the legacy pockets of inequity in black and brown communities. The time to act is now! Because if we choose to wait—and it will be a choice—we will once again miss an opportunity to ensure that the very same people who are keeping our recovery afloat can finally be treated equally.

Stephen F. Gray is an Assistant Professor of Urban Design at Harvard Graduate School of Design and founder of Boston-based design firm Grayscale Collaborative . His work acknowledges the intersectionality of race, class, and the production of space, and he is currently co-leading an Equitable Impacts Framework pilot with the High Line Network and Urban Institute aimed at advancing racial equity agendas for industrial reuse projects across North America. This op-ed was originally published on nextcity.org , a nonprofit news site with a mission to inspire greater economic, environmental, and social justice in cities.

GSD participates in global, open-source effort to develop patient isolation hoods for Boston hospitals

Harvard University Graduate School of Design announces the rapid development of patient isolation hoods (PIH), in collaboration with clinicians at Mass General Brigham’s (MGB) Center for COVID Innovation and Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH). The GSD’s efforts have involved hundreds of designers, technical experts, and medical professionals from around the world in a community-led, open-source process, one that participants say could be a model for future modes of collaborative work and design.

Within two weeks, the design team was able to conceptualize and produce four flexible, lightweight PIH prototypes, delivering three to MGH on April 22 and one to BCH on April 24 for in-clinic evaluation. Patient isolation hoods act as a barrier between patients and healthcare providers to reduce providers’ risk of exposure to viruses and other contaminants during medical procedures.

Alongside the production of physical PIH, this collaborative process of design and evaluation has provoked reflections on the effort’s global, open-source, grassroots nature. Drawn from around the world and from various fields of study and expertise, more than 200 participants produced their designs and evaluations almost entirely via digital platforms, enabling the effort to be global in scope, rapid in pace, and uniquely collaborative.

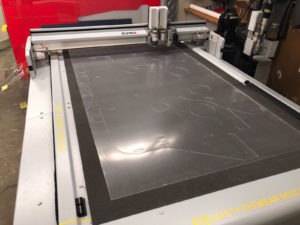

“These patient isolation hoods are intended to be used in an environment that has extremely high and rigorous standards, and a normal structure and process of design and prototyping would take months or years to accomplish,” says Chris Hansen, digital fabrication specialist at the GSD’s Fabrication Laboratory . “Here, a design has been prototyped and put into a clinical environment in under a month. That was possible only by taking a new, non-hierarchical approach to design development, in which everyone is donating time and energy, and all stakeholders are empowered to make decisions independently.”

The GSD’s Fabrication Lab served as a production site throughout these PIH design efforts; equipped with CNC routers, laser cutters, Zund cutter, 3-D scanners, and other state-of-the-art technology, the Fabrication Lab ordinarily produces physical models for the GSD’s architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning, and urban design students and faculty.

These cross-institutional PIH efforts arose amid previously established, ongoing GSD work with the MGB Center for COVID Innovation, whose mission includes protecting front-line clinical staff and facilitating innovations that reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission. Throughout March and April, the GSD—most specifically, its Fabrication Lab staff—produced thousands of 3-D-printed face shields and other personal protective equipment, or PPE, for MGB. By May 7, the GSD had fabricated close to 3,200 face shields and 2,200 face visors.

At the close of March, an ongoing Slack-based conversation among designers, doctors, and other contributors dedicated to PPE design had added PIH design to its focus. In consultation with participating doctors and clinicians, the collective team identified 25 critical design requirements for such hoods, including easy access for doctors’ arms and medical tools, rapid retractability in case of emergency, and negative air pressure, or suction, to move contaminants and air particles away from the attending doctor. Several days of meetings, design iterations, and test fabrication followed.

By April 10, after reviewing a series of PIH models, the team had developed consensus on one optimal design, dubbed “Apollo.” An “Apollo” prototype was delivered to Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) on April 12 for clinical tests, after which it was approved for clinical use. Additional full-scale, fully operational “Apollo” prototypes were then fabricated at the GSD, three of them delivered to MGH on April 22 and one delivered to BCH on April 24. See an open-source compilation of “Apollo” design files via GitHub .

The design team’s various PIH prototypes are designed to function across hospital settings, whether emergency room, intensive care unit, or otherwise, and to allow ease of assembly, use, and disposal; they are composed of flat sheets of PETG plastic, with minimal need for joinery or panel construction. As an open-source design, the hoods can be fabricated anywhere in the world.

The PIH design and production process has inspired new perspectives on how design and medicine may join forces, throughout and beyond the ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

“The design process was unprecedented, partially because of the speed at which it was conducted, but also because of its ground-up, open-source, and collaborative design process,” observes Dr. Samuel Smith, MD, an anesthesiologist at MGH and instructor at Harvard Medical School (HMS) who participated in clinical review of these prototypes.

“Doctors and medicine need designers and design; good design leads to better, more effective equipment and resources, and eases physicians’ cognitive burden and fatigue. Despite the circumstances of this pandemic, the sight of so many doctors, designers, and others from around the world pooling expertise for the sake of a single effort has been empowering, giving us hope on many levels.”

2020 graduate Juan Reynoso bridges the worlds of public health and urban planning

Excerpted from a Harvard Gazette series of profiles showcasing some of Harvard’s stellar graduates.

Juan Reynoso is about to step into largely uncharted territory. When he graduates this spring, he’ll be only the second person to have completed a new joint Master in Public Health (MPH)/Master in Urban Planning (MUP) degree program . Launched in 2016 by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Harvard Graduate School of Design, the program allows students to pursue a transdisciplinary education in urban planning and public health and sharpen their understanding of key areas including policy, sustainability, and social determinants of health .

Over the course of the program, Reynoso has bounced between studios at GSD, where he’s wrestled with urban planning challenges, and classrooms at Harvard Chan School, where he’s learned about population health and has grown especially interested in how environmental exposures, such as air pollution or tainted drinking water, affect health.

“It’s so interesting because each graduate School at Harvard has its own culture, its own pedagogy, its own way of thinking,” Reynoso says. “This program has allowed me to break out of those silos. And that’s helped me to better make connections among a wide variety of disciplines so I can analyze how certain urban planning efforts have health co-benefits or how certain health interventions have environmental benefits.”

Pollution in the valley

Reynoso’s interest in the intersection of health and design traces back to his parents. They were born in rural Mexico and immigrated to California, living first outside of Los Angeles and later moving to the Central Valley — the inland stretch of California that’s one of the most important agricultural hubs in the world. “I was born in Tulare County, which is a pretty rural agricultural area that consistently has some of the worst air quality and water quality in the country,” he said.

As a young boy, Reynoso was oblivious to the air pollution that drifted into the valley from nearby cities and the myriad pesticides that doused the surrounding farmland and would get kicked up into the atmosphere when strong winds swept through. Looking back now, he can’t help but wonder whether the environment of Tulare County was harming him. “I was very sickly as a child,” he recalled. “I missed half of my kindergarten year because I was always ill with respiratory diseases. How is a child supposed to be successful when the environmental exposures surrounding them are making them sick?”

Reynoso’s family eventually picked up and moved to Escondido, a city in San Diego County. The difference in his health was “night and day,” he said. “Rather than miss half the school year, I’d miss like 10 days at most.”

Reynoso was an excellent student and by high school his schedule was stacked with advanced placement classes. Around the same time, a series of wildfires tore through Southern California and came unsettlingly close to Escondido. Smoke and haze lingered in the air and Reynoso started wondering what that meant for his and his community’s health. “I was taking a class in environmental science at the time, and all these things started clicking for me,” he said.

With these experiences in mind, Reynoso chose to major in human biology with a concentration in environmental health at Stanford University. After graduating, he joined The California Endowment, a statewide foundation focused on health. While there, he worked on its Building Healthy Communities initiative, exploring a wide range of issues that sat at the intersection of policy, urban planning, and health, including active transportation and community land use.

Bridging disciplines

When Reynoso began exploring graduate schools, the joint MPH/MUP program hit all the right notes. It blended his interests and fit his ambitions to improve community health through cross-disciplinary strategies.

“Juan is an energetic problem solver. As one of the first students in the joint MPH/MUP program, he has been active in helping to build a community of students. As a leader in the Healthy Places Student Group at the GSD, an area of growing student interest, Juan has been really active in organizing events and promoting dialogue,” said Ann Forsyth, Ruth and Frank Stanton Professor of Urban Planning and director of the Master in Urban Planning Program at the GSD.

Joseph Allen , assistant professor of exposure assessment science at Harvard Chan School, said it’s heartening to see students like Juan push the field of public health forward. One of the shortcomings in Allen’s own public health training, he said, was a lack of focus on building science , design, and urban planning. “Juan is working to bridge the gap between these disciplines,” Allen said. “He really is a pioneer.”

Reynoso isn’t sure what his next step will be after he graduates. But he knows that he wants to tackle some of the biggest health and environmental challenges in a way that prioritizes equity and justice. He thinks back often to his childhood in the Central Valley, and of the disparities that persist across his beloved home state. He hopes that his training at Harvard can help remedy some of these problems.

“California is the richest state in the richest country in the world, and there are millions of people who don’t have access to clean drinking water or who are constantly exposed to air pollution or who are harmed by the environment in which they live in myriad other ways,” he said. “We need to work collectively in order to solve the public health challenges of today.”

GSD names Jenny Odell the 2020 Class Day speaker

Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design has named Jenny Odell as its 2020 Class Day speaker. Odell will address the GSD’s Class of 2020 and their families during Harvard’s 2020 graduation exercises on Thursday, May 28. Odell’s talk is scheduled to begin approximately at 1:10 p.m. EST, to be streamed live on the GSD’s YouTube channel.

Artist and author Jenny Odell

Odell is an Oakland-based, multidisciplinary visual artist and writer whose work encourages close observation of the everyday. She has been an artist in residence at the San Francisco Planning Department, the Internet Archive, and Recology SF (a.k.a. “the dump”), and has exhibited at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, the New York Public Library, the Marjorie Barrick Museum (Las Vegas), Les Rencontres D’Arles, Fotomuseum Antwerpen, Fotomuseum Winterthur, La Gaîté Lyrique (Paris), the Lishui Photography Festival (China), and East Wing (Dubai). Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, New York magazine, the Paris Review, Sierra magazine, and McSweeney’s. Odell has taught studio art at Stanford University since 2013.

Odell’s New York Times-bestselling book, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, was published by Melville House in 2019. The New York Times Book Reviews praised How to Do Nothing as “A complex, smart and ambitious book that at first reads like a self-help manual, then blossoms into a wide-ranging political manifesto.” The book was named a “best book of the year” for 2019 by a variety of critics and outlets, including Time magazine, The New Yorker, NPR, GQ magazine, Elle magazine, and Fortune magazine.

In 2016, feeling a sense of inability to create art, Odell found herself sitting and “doing nothing” in Oakland’s Rose Garden. It is there she formed the ideas that became How to Do Nothing, which she first discussed in a lecture at the 2017 EYEO technology conference and later posted on Medium, which went viral. In How to Do Nothing, Odell applies the lenses of art, philosophy, literature, historical events, and science to challenge readers to take a deeper look at the forces vying for our attention and how we respond. She describes human attention as the most precious—but the most overdrawn—resource we have. She observes that once people start paying a new kind of attention—one that transcends narratives of efficiency and techno-determinism—people can undertake bolder forms of political action, reimagine our role in the environment, and arrive at more meaningful understandings of happiness and progress.

To see a full schedule of 2020 Class Day and Diploma Ceremony exercises, please visit the GSD’s Commencement webpage.

Remembering Iraqi architect, photographer, author and activist Rifat Chadirji (1926-2020)

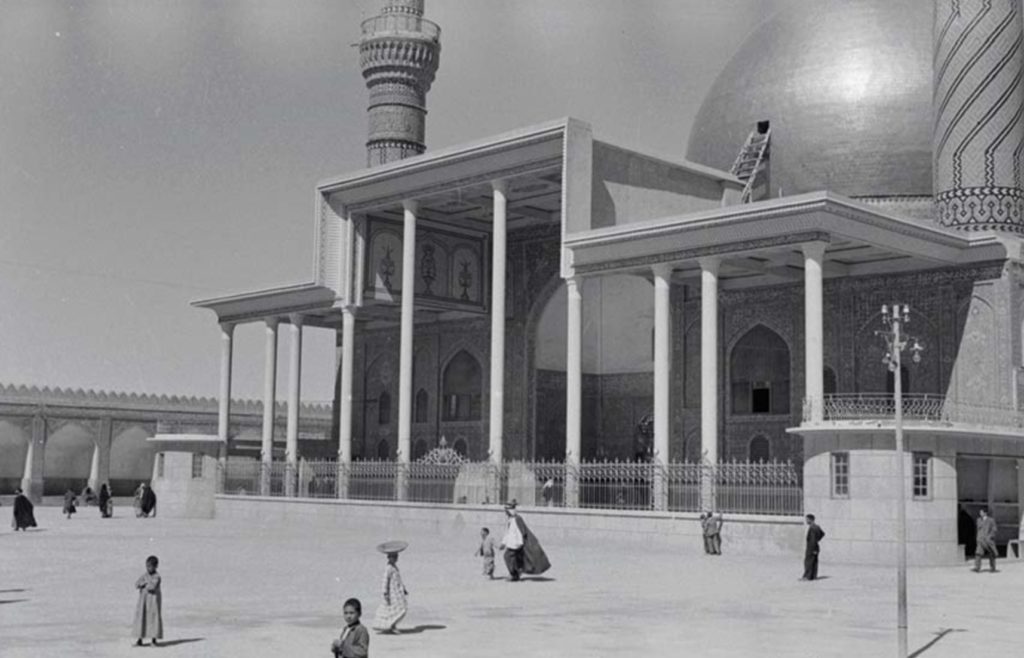

“Rifat Chadirji was a Loeb Fellow in my class of 1983. He and his wife, Balkis Sharara, became good friends and we saw each other socially both during the Loeb year and afterward, although we have not been in touch for many years.

Rifat had already had a long and distinguished career in Iraq by the time he was a Fellow. I seem to recall that he arrived in Cambridge in good part due to the help of The Architects Collaborative (TAC). Along with the Bauhaus, TAC was a major influence on his work to rebuild and modernize Baghdad.

The whims of the Baath regime had landed Rifat at Baghdad’s Abu Ghraib prison in 1978, and the whims of Saddam Hussein got him out two years later. For much of that time, Balkis didn’t hear from him or know where he was. Finally, Hussein made him his architectural adviser and tasked him with rebuilding Baghdad as a utopian metropolis in time for a major conference in 1982. Rifat had two choices: accept the commission or stay in prison.

After several years of working for Hussein, TAC helped Rifat to get a Loeb Fellowship. He subsequently left Iraq and lived first in Cambridge and later in London and Lebanon, Balkis’s home country. He continued to work, teach, and figure prominently in his field until his death from COVID-19 on April 10, 2020 at the age of 94.