When the High Tech Abounds, the Low Tech Shines: A Review of the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale

Across from the main entrance to the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale stands a courtyard lined with bamboo scaffolding. An ancient Chinese structure fashioned with lashed bamboo poles, such scaffolding dates back thousands of years and remains ubiquitous throughout Hong Kong, wherever construction is underway.

This particular bamboo scaffolding, erected in a Venetian courtyard, serves a different purpose: it is both set piece and enticement, part of a collateral event called Projecting Future Heritage: A Hong Kong Archive , curated by GSD alumni Fai Au (MDes ’11) and Ying Zhou (MArch ’07) with Sunnie Sy Lau. The scaffolding draws in visitors, showcasing its artful existence while leading to an adjacent warehouse-turned-gallery that catalogs examples of Hong Kong’s post-war building typologies and infrastructures.1 Employing natural materials and collective practices, the bamboo scaffolding evokes a sense of ingenuity and timelessness.

This year’s architecture biennale, also known as the 19th International Architecture Exhibition, carries the theme “Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective. ” Explaining this title, curator Carlo Ratti aligned the Latin intelligens with multiple forms of knowledge available to humankind. (Gens, after all, is Latin for people). Nevertheless, since the biennale opened last month, reviews—including “A Tech Bro Fever Dream” and “Can Robots Make the Perfect Aperol Spritz?” — have largely focused on the omnipresence of technology. True, the high tech abounds in a range of guises, from algae-infused building materials to sensor-ladened space skins. Yet, even as the dangling automatons and LiDAR maps underscore the “Artificial,” an expansive understanding of intelligence, one that embraces the “Natural” and the “Collective,” remains palpable, especially among contributions by members of the GSD community. This undercurrent surfaces through visitors’ “low tech” experiences with sensorial input, animal encounters, and communal engagement.

A Multisensory Biennale

The 2025 Architecture Biennale encompasses 300 installations, 66 National Pavilions, and 11 collateral events (as well as more than 100 GSD-affiliated contributors). Given this concentration of projects, one would anticipate an array of sights, sounds, scents, and atmospheric conditions. What appears striking, however, is the number of projects that rely on visitors’ immersive and multisensory involvement for full effect.

While most installations discourage hands-on interaction (“non toccare!”), tactile sensation nonetheless reigns supreme. This begins with Ratti’s main exhibition, staged primarily in the Arsenale’s Cordiere (a former rope factory/warehouse), which opens with the project Terms and Conditions . Here visitors move from the bright Venetian sunlight to a dim, muggy vestibule containing the waste heat from the air conditioning system that maintains the vast hall beyond at a comfortable 23 degrees Celsius (73.4 degrees Fahrenheit). The oppressive heat envelops visitors, offering them a glimpse of Venice’s projected future climatic conditions as they move beneath suspended air conditioning units, finally emerging into the Cordiere’s cool, light-filled, low-humidity interior where hundreds of exhibits await.

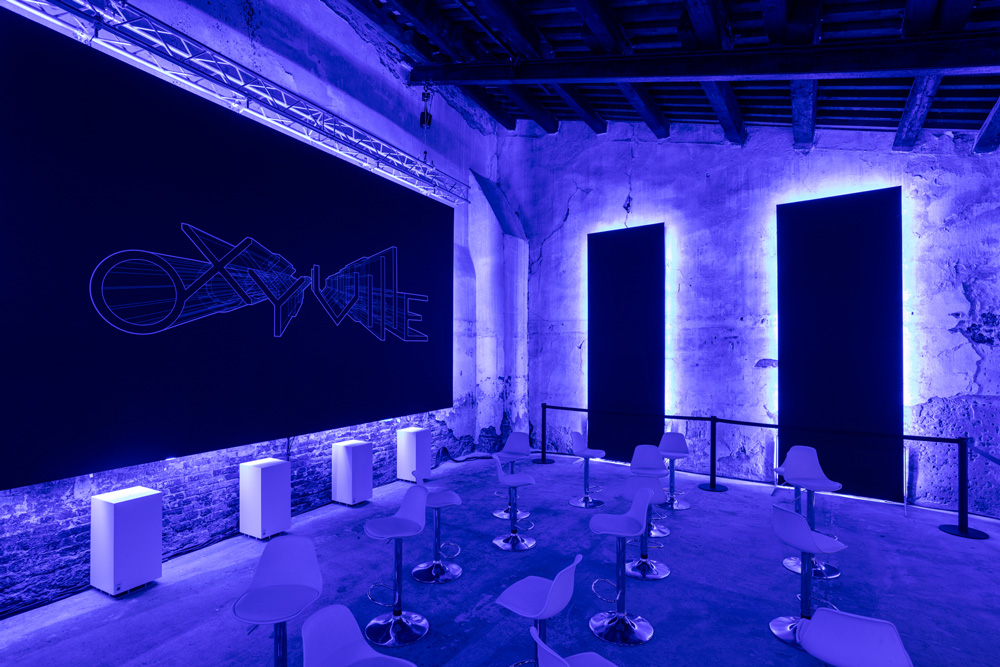

The immersive experiences continue with installations that cloak visitors in sound—dripping water; awe-inspiring music reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 Space Odyssey; humming frequencies, and more. One such exhibit—Oxyville by Jean-Michel Jarre, Maria Grazia Mattei, and GSD professor Antoine Picone—uses electronic music to explore the relationship between 3D audio and architecture. Within a space illuminated by glowing blue lights, visitors experience soundtracks that conjure different “sonic architectures,” such as that of a cathedral or, perhaps, a nightclub.

Other exhibits involve perceptible odors. Their inclusion isn’t necessarily intentional, although it is for some installations, such as Sound Greenfall and Grounded , the Türkiye Pavilion. Still, in many circumstances, discernable aromas become integral experiential components of a given project. For example, with its dense concentration of indoor microclimate-producing plants, Building Biospheres —the Belgium Pavilion, curated by GSD professor Bas Smets and Stefano Mancuso—proves incredibly fragrant. Meanwhile, the rectangular blocks of earth (chinampas) that populate Chinampa Veneta , the Mexico Pavilion, evoke the shallow-water environments in which these life-supporting landscape elements traditionally float.

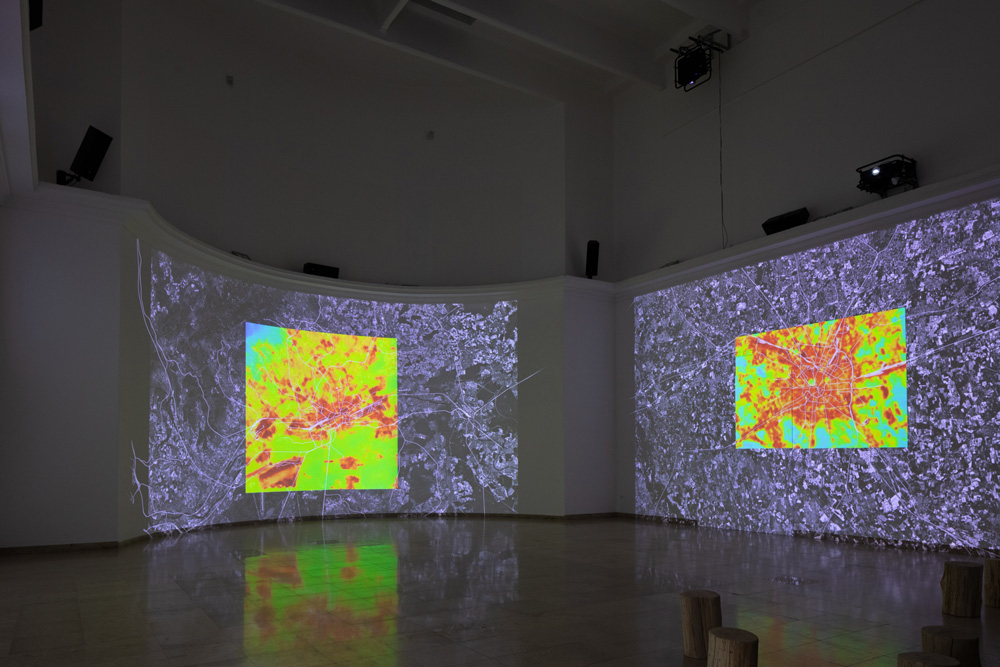

The exhibits are diverse visually, with intriguing dynamic elements and textured surfaces—smoke, water, lava, wood, vegetation—to catch one’s eye. Film features prominently, at times animating wrap-around enclosures to immerse visitors in the imagery. Stresstest , the German Pavilion (which includes a project by GSD alumni Frank Barkow [MArch ’90] and Regine Leibinger [MArch ’91]), employs this strategy, filling three walls of the pavilion’s soaring main space with infrared heat maps and alarming news footage of warming city centers. (A tolling bell—our planet’s death knell?—sounds in the background). Former GSD Loeb Fellow Tosin Oshinowo (LF ’25) harnesses a similar approach on a smaller scale for Alternative Urbanism: The Self-Organized Markets of Lagos . This installation’s screens surround visitors with the bustling activity of three Nigerian markets that recirculate so-called waste items from industrialized societies (clothing, auto parts, and more)—repairing, altering, and reusing them to create a sustainable system that transcends conventional patterns of consumption.

While planning the 19th International Architecture Exhibition, Ratti and his curatorial team no doubt recognized that all this sensory input could prove overwhelming. Perhaps this is one reason behind the minimalist AI descriptions that appear, in English and Italian, alongside the designers’ longer project explanations. Some may be disturbed by these pared-down depictions, at times a mere two sentences versus the designers’ original multi-paragraph text; have critical nuances been lost? Is this a commentary on the human attention span? Does architectural discourse really require such CliffsNotes? All these may well be the case. Yet, after experiencing a few dozen installations and realizing hundreds more await, it becomes clear that, whatever else they may be, the AI descriptions are a kindness, a “low-power mode” for visitors’ mental stamina as they undertake this endurance event. An added bonus: the AI text ruthlessly eliminates the discipline’s notorious archi-speak, in theory making the biennale more accessible to the public, including the mass of tourists who roam the Venetian cobblestone streets.

Animal Encounters

Aside from thieving seagulls and Piazza San Marco’s iconic winged lion, animals aren’t often associated with Venice, by said tourists or locals. A number of biennale installations seek to change this, including The Living Orders of Venice by Studio Gang, led by GSD professor Jeanne Gang. This project uses iNaturalist , a citizen science app, to enact a Biennale Bioblitz : a crowd-sourced field study to document local animal activity during the show’s 6-month run. In addition, the firm’s exhibit in the Cordiere showcases prototypical habitats to accommodate Venice’s non-human residents—the birds, bats, and bees displaced throughout centuries of construction, which destroyed their natural architectures. Instrumental for the planet’s health, these creatures require appropriate homes in increasing crowded urban centers, and Studio Gang proposes species-specific abodes to complement Venice’s existing classical architecture.

Architecture for animals likewise plays a role in Song of the Cricket , which models a rehabilitation effort for endangered species—in this case, the Adriatic Marbled Bush-Cricket, believed extinct for fifty years before its 1990s rediscovery in the wetlands of northeastern Italy. Alongside integrated research and monitoring programs, Song of the Cricket offers modular, floating islands as portable breeding stations that reintroduce healthy cricket populations to the Venetian Lagoon. Emblazoned with “BUSH-CRICKETS ON BOARD,” these temporary habitats support multiple cricket lifecycles, reducing threats of predation and disease. Other components of the project include a sound garden featuring the crickets’ song, described “as a bioindicator of ecosystem health,” unheard in Venice for over a century.

Similarly, animals emerge as crucial contributors in the Korea Pavilion, titled Little Toad, Little Toad: Unbuilding A Pavilion . With the project Overwriting, Overriding , exhibitor/GSD alumna Dammy Lee (MArch ’13) turns to the structure’s non-human occupants—a large honey locust tree and Mucca, “the [cow-spotted] cat who roams the space as if it were its own home”—to interrogate the pavilion’s history, highlighting the “hidden entities that have silently coexisted with the pavilion.” The installation 30 Million Years Under the Pavilion , by artist Yena Young, complements this narrative with a camera mounted beneath the structure to document unexpected visitors. The footage reveals that Giardini critters regularly frequent this and presumable all pavilions, which typically remain closed to the public when a biennale is not in session. (One is reminded of Remy the Cat, the unofficial GSD mascot who trapses through Gund Hall at will.) Thus the Korea Pavilion, built in 1995 yet reminiscent of Le Corbusier’s designs of the 1920s, serves as a home for not just the architects, artists, curators, and works they produce, but also cats (Mucca and two others), mice, birds, spiders, flies, and even a hedgehog—all cataloged by hand in pencil below wall-mounted Ipads that depict their visits. Amid the hi-tech fanfare that characterizes much of the 2025 Architecture Biennale, the ease, simplicity, and whimsy of Lee’s and Young’s projects, in conception and execution, feels particularly powerful.

The Power of Community

The Polish Pavilion, Lares and Penates: On Building a Sense of Security in Architecture , offers another commanding and clever presentation that shines among the National Pavilions. Infused with its own dose of whimsy, this exhibition zeros in on the ways in which architecture creates a sense of security, relying on two concepts from two very different communities: solutions derived from conventional building and health regulations, such as roofs, electrical codes, and evacuation signs; and others rooted in traditional Slavic cultural practices like brandishing dowsing (divining) rods to determine fortuitous home placement, installing horseshoes in doorways for luck, and burning smudge sticks to banish negative energy from a space. Lares and Penates, defensive household deities of Ancient Rome, lend their name to the exhibition while its designers present these security-bestowing practices as equally valid, complementary elements that, as a brochure accompanying the pavilion states, “help people feel more secure in a swiftly changing reality.” This non-judgmental approach is exemplified by the placement of a bright red fire extinguisher at the heart of a stone-and-shell encrusted niche. Fire codes, after all, are sacred in their own way.

While highlighting the human desire for security, the Polish Pavilion also alludes to our innate tendency to find strength in community, to connect with others to share ideas, resources, and support. Since its inception in 1980, Venice’s International Architecture Exhibition has embodied this urge for the cultivation of community on a global scale. That people today continue to congregate for the biennale, even though digitalization makes it possible to distribute knowledge without transcontinental trudging, indicates that many still yearn for actual (versus virtual) contact. Two installations openly address this impulse, as they provide platforms for present-day gathering and discussion. At the same time, they offer clear connections to the biennale’s communal past.

The Speakers’ Corner , by Christopher Hawthorne, former Loeb Fellow Florencia Rodriguez(LF ’14), and GSD design critics Sharon Johnston (MArch ’95) and Mark Lee (MArch ’95), who comprise the firm Johnston Marklee, offers a forum for workshops, lectures, and panels within the Cordiere. The inspiration for this sixty-person grandstand, made of unfinished white pine, stems from the 1980 Architecture Biennale—specifically, I Mostri d’Critici, curated by architectural historians/critics Charles Jencks, Christian Norberg-Shulz, and Vincent Scully, underscoring the disciplinary role of criticism and discourse. Throughout the 2025 biennale’s run, the Speakers’ Corner is hosting a series of events focused on future possibilities for architecture criticism—including those posed by the emerging role of artificial intelligence, as signaled by the biennale’s AI project descriptions.

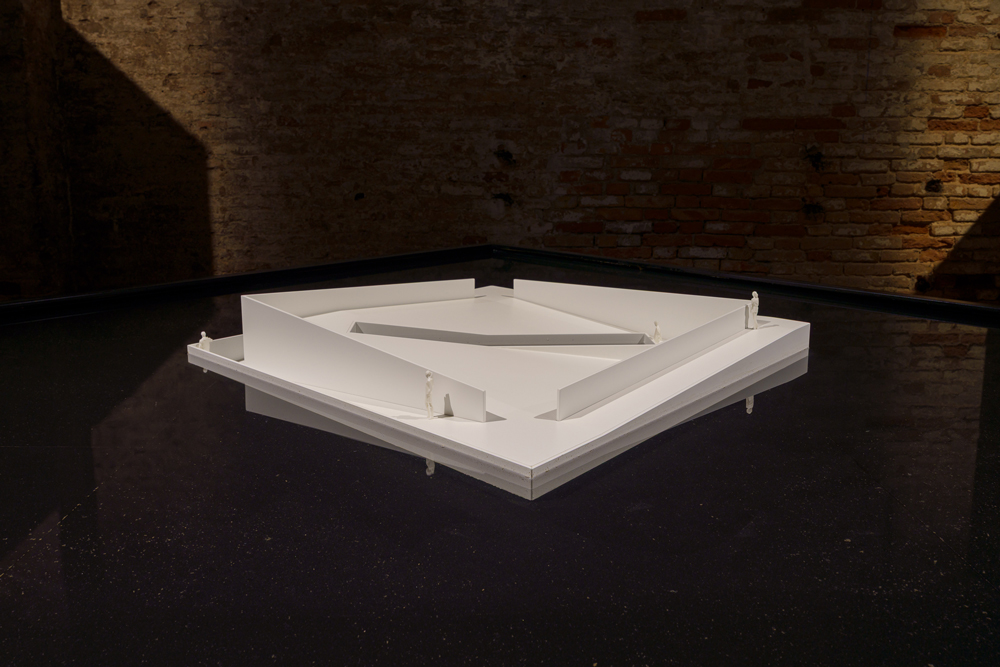

The other installation that highlights collective gathering and this biennale’s connection with the past is Aquapraça by CRA – Carlo Ratti Associati and Höweler + Yoon (founded by GSD professor Eric Höweler and alumna J. Meejin Yoon [MAUD ‘02]). Envisioned as a floating plaza to prompt discussions around climate change, this 400-square-meter entity will debut in the Venice Lagoon on September 4 before migrating across the Atlantic Ocean to join COP30 in Belém, Brazil, in November of this year. (A large model of the floating platform is currently on display in the Cordiere.) Aquapraça’s pure geometries recall those of Aldo Rossi’s Teatro del Mondo of 1979, a floating wooden theater that became an icon of the First Architecture Biennale before traveling via tugboat to Dubrovnik.

It is no accident that both the Speakers’ Corner and Aquapraça echo the aesthetic simplicity and communal intent of Rossi’s aquatic building. These projects illustrate the human desire to gather, to experience sights, sounds, and environments in real life. The sustained existence of the biennale attests to the continued significance of collective intelligence as well as creating places and events that bring people together.

- In addition to Fai Au (MDes ’11) and Ying Zhou (MArch ’07), Projecting Future Heritage includes many GSD affiliates. Jonathan Yeung (MArch ’20) and Wing Yuen (MArch ’22) are part of the curatorial team. Exhibitors include Max Hirsh (PhD ’12) and Dorothy Tang (MLA ’12) with Airport Urbanism: Remaking Hong Kong, 1975–2025; Su Chang (MArch ’17) and Frankie Au (MArch ’16) of Su Chang Design Research Office with Made in Kwun Tong: Between Type and Territory; and Betty Ng (MArch ’09), Chi Yan Chan (MArch ’08) and Juan Minguez (MArch ’08) of Collective with Pixelated Landscapes. ↩︎

Summer Reading 2025: Design Books by GSD Faculty and Alumni

Whether you plan to read in the summer sunshine or an air-conditioned lounge, these recent books by Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) faculty and alumni conjure environments from the semi-arid Mezquital Valley to the frozen Arctic tundra.

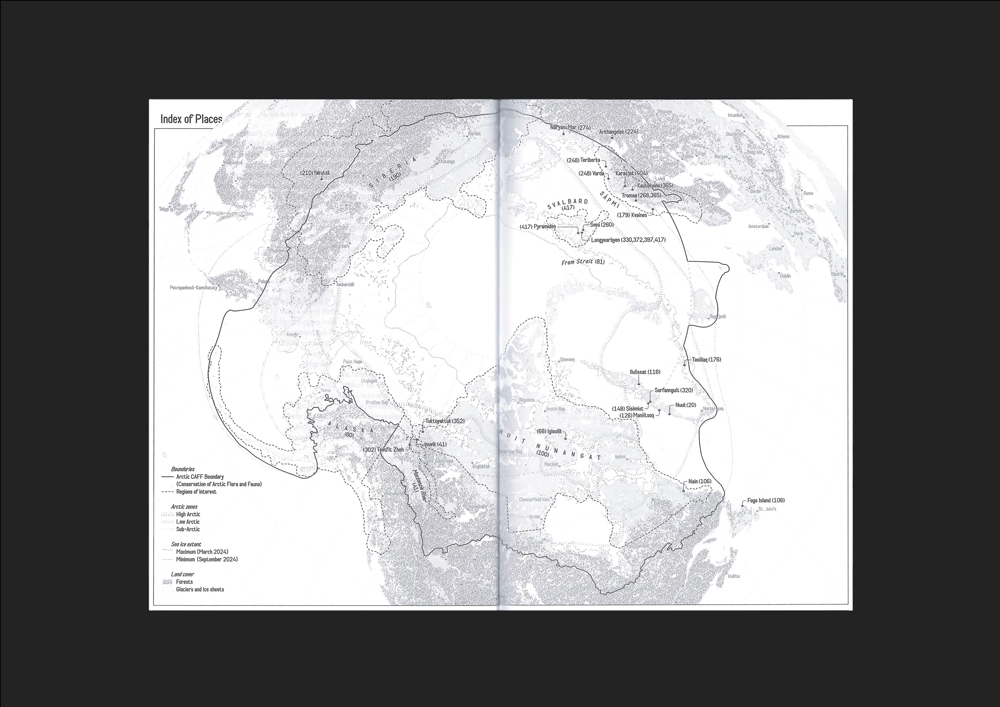

Arctic Practices: Design for a Changing World (Actar, 2025), edited by GSD lecturer in landscape architecture Bert De Jonghe (MDes ’21, DDes ’25) and Elise Misao Hunchuck, confronts two issues critical for Arctic lands: the climate crisis and the need for anticolonial reconciliation. Gathering texts by authors in the fields of design, education, and the arts, the collection offers diverse perspectives on current and future design interventions, all grounded within the Arctic’s distinct environmental and historical context.

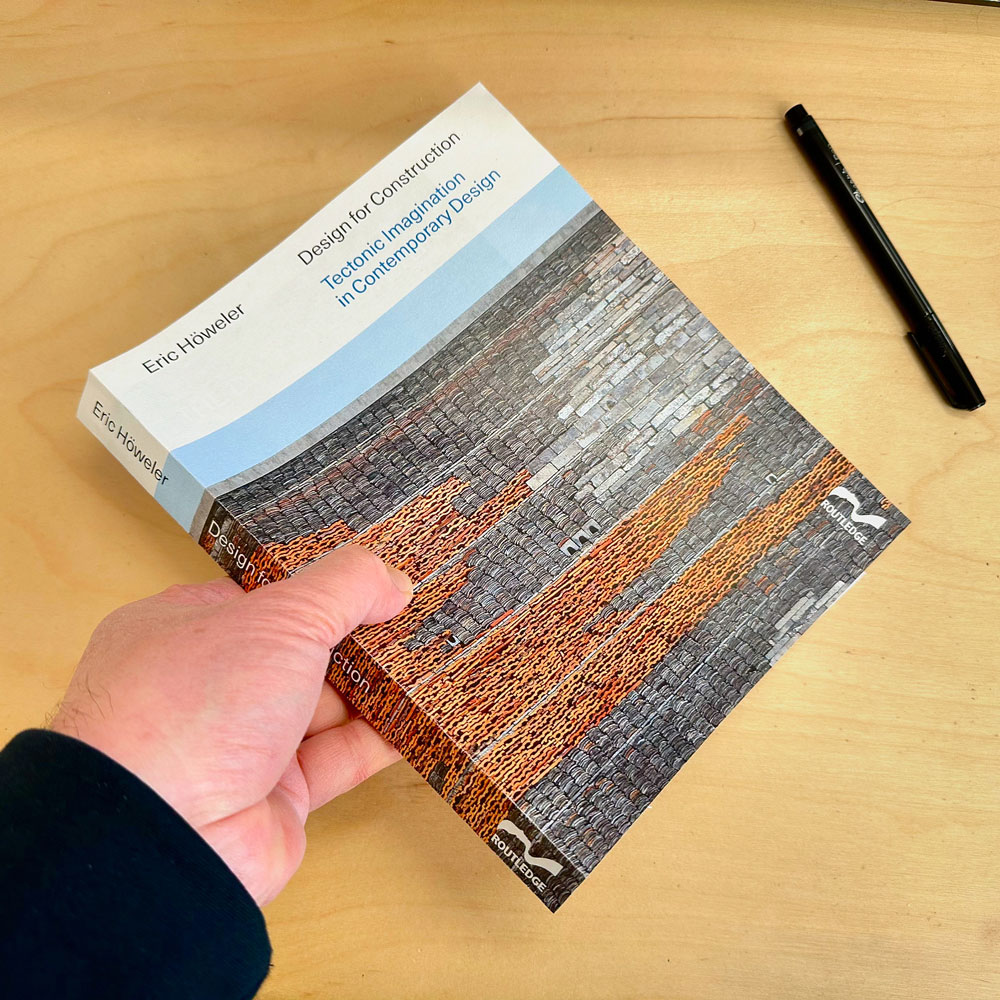

Design for Construction: Tectonic Imagination in Contemporary Architecture (Routledge, 2025), by Eric Höweler, professor of architecture and director of the Master of Architecture I program, bridges conceptual thinking and practical building techniques. The book delves into topics such as materials research and construction sequencing, dissecting projects by leading practitioners (including GSD-affiliates Barkow Leibinger, Johnston Marklee, MASS Design, NADAA, and others) as illustrative examples. As the discipline contends with its ecological and social impacts, re-engaging with design and building offers an opportunity for architects to assert agency while working toward a better future.

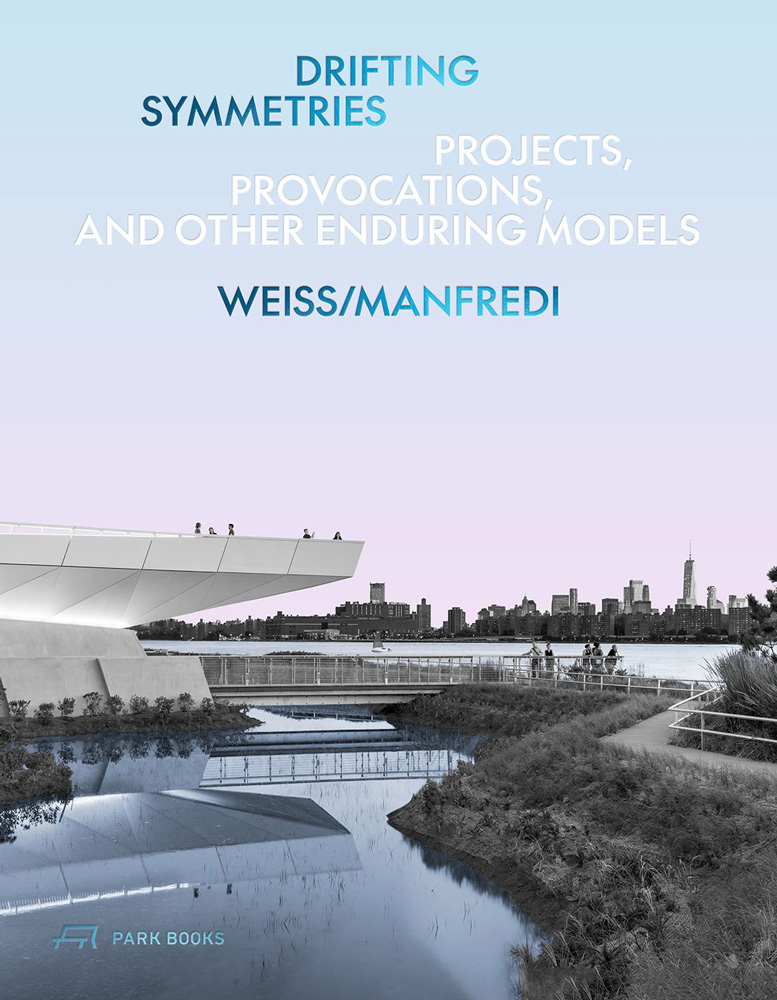

Drifting Symmetries: Projects, Provocations, and Other Enduring Models (Park Books, 2025), by Marion Weiss and Michael Manfredi, design critic in urban planning and design, features projects by the New York City–based architecture practice Weiss/Manfredi. Alongside the firm’s work—which is characterized by a multidisciplinary approach that melds architecture, landscape, and infrastructure—the book presents commentary from leading architects such as Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture Sarah Whiting, John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization Rahul Mehrota, Hashim Sarkis (MArch ’89, PhD ’95), Nader Tehrani (MAUD ’91), and Meejin Yoon (MAUD ’97), among others.

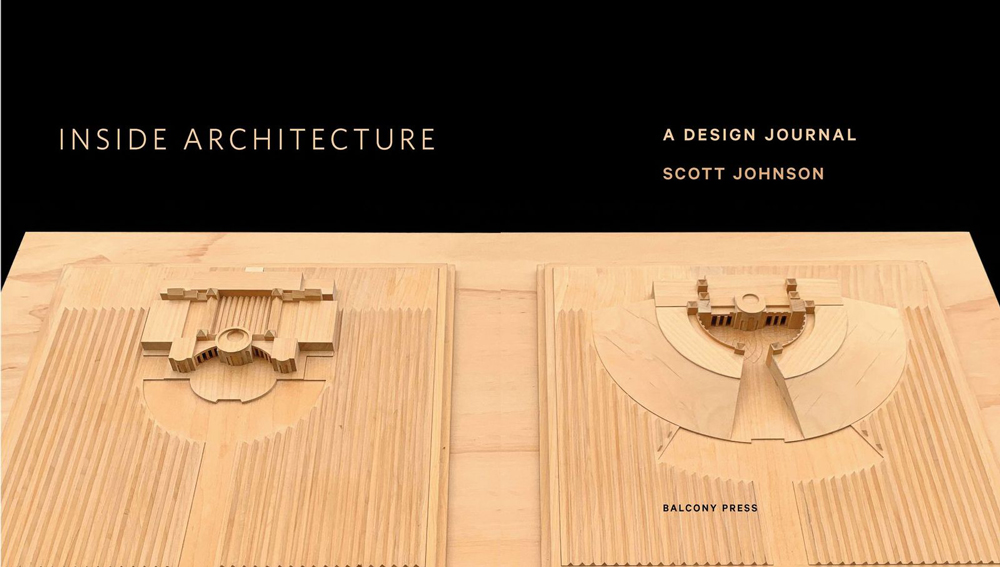

Inside Architecture: A Design Journal (Balcony Press, 2025) by Scott Johnson (MArch ’75), FAIA, is structured as a personal and professional retrospective, offering a glimpse into the creative process of one of Los Angeles’s most accomplished architects. Combining candid narrative (including thoughts on his student years at the GSD), project case studies, and design commentary, Johnson reflects on the buildings, cities, and ideas that have shaped his decades-long career as the design partner and cofounder of the firm Johnson Fain.

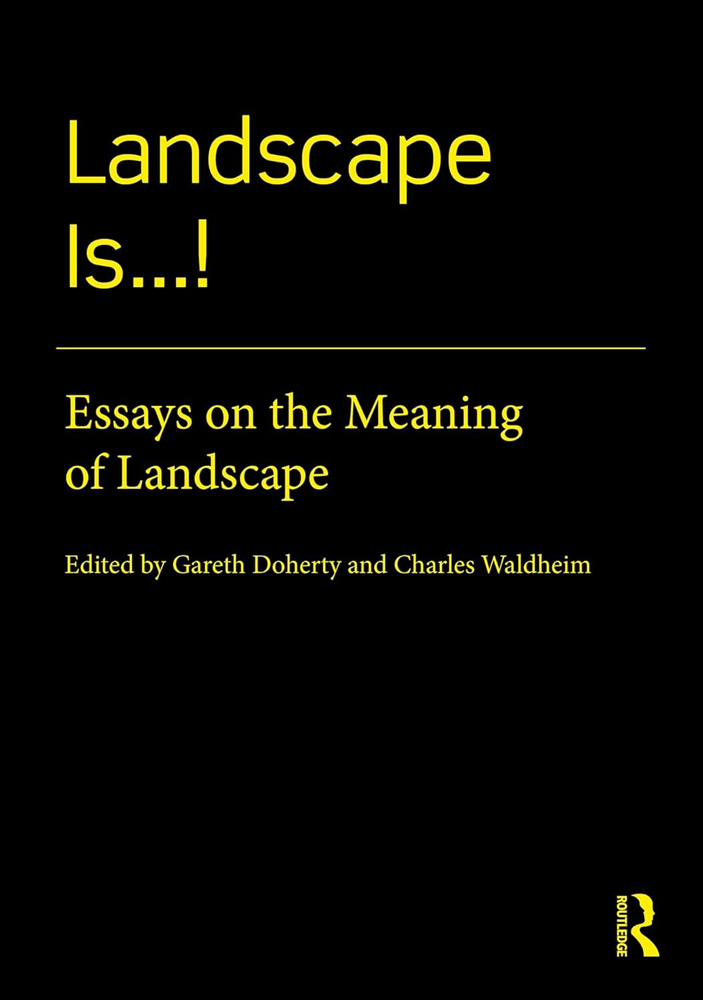

Landscape Is . . . !: Essays on the Meaning of Landscape (Routledge, 2025) explores various meanings of landscape as a discipline, profession, and medium. Edited by Gareth Doherty (DDes ’10), associate professor of landscape architecture and affiliate of the Department of African and African American Studies; and Charles Waldheim, John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture and co-director of the Master in Design Studies program, this collection is a companion volume to Is Landscape…?: Essays on the Identity of Landscape , released in 2016.

Thinking Through Soil: Wastewater Agriculture in the Mezquital Valley (Harvard Design Press, 2025), by former Dan Urban Kiley fellows Monserrat Bonvehi Rosich (2017–2018) and Seth Denizen (2019–2021), offers an analysis of the world’s largest wastewater agricultural system, located in the Mexico City–Mezquital hydrological region, to envision an improved future environment in central Mexico. This case study presents soil as an everchanging entity that is critical for the health of the planet and all its inhabitants.

Vembanad Lake and Its Untold Stories: Ecological Fragility, Food Sovereignty, and Sustenance Habitability (Notion Press, 2025), by Hasna Sal (MDes ’25), interrogates the historical evolution, ecological challenges, and socio-economic transformations of Vembanad Lake—the longest lake in India, and the largest in the state of Kerala—over the past century. Integrating cartographic and diagrammatic analysis with oral histories by fisherman, oceanographers, and more, the book advocates for a transdisciplinary framework that values localized, experiential knowledge as essential for designing inclusive conservation strategies that support environmental stewardship and social justice.

Sarah Dennis-Phillips (MLA ’00) Named Planning Director of the City of San Francisco

Sarah Dennis-Phillips (MLA ’00) has been announced as the new Planning Director for the City of San Francisco. Appointed by Mayor Daniel Lurie in June 2025, she is the first woman to serve in this role. Sarah previously worked as Executive Director of the Office of Economic and Workforce Development for the City of San Francisco.

In a press release from the City , Sarah shared, “I am honored to be tapped by Mayor Lurie to support his vision for San Francisco and direct the Planning Department in accelerating housing development across income bands through his Family Zoning plan, unlocking pipeline projects, and incentivizing adaptive reuse of commercial properties…I’m excited to help guide the city into its next phase of revitalization—one focused on long-term transformation, regulatory reform, and building the foundation for the kind of sustainable, inclusive innovation that defines San Francisco at its best.”

Photo courtesy of Sarah Dennis-Phillips (LinkedIn ).

Plimpton-Poorvu Design Prize

Hours

Mon-Fri: 9a.m.–5p.m.

The Plimpton-Poorvu Design Prize is now accepting applications.

All submissions are due at 12:00 pm (noon, EDT) on Friday, January 17, 2025. Start the process sufficiently prior to noon in order to ensure your submission has time to upload fully before the deadline.

The 2024–25 competition committee is composed of faculty from all departments, including Mohsen Mostafavi (committee chair), Jungyoon Kim, George Legendre, Anne-Marie Lubenau, Maurice Cox, and Frank Apeseche (special advisor).

Questions may be submitted to Amanda McMahan, Director of Administration, Office of the Dean.

A recording of the PPDP student information session held on October 29, 2024 is available below for reference.

How to apply

To apply, please submit a PDF document that includes the information requested below to the OneDrive File Upload Link by 12:00 pm EST on Friday, January 17, 2025. Applications submitted after the deadline will not be considered.

Applications must include the following three components in one PDF document with the filename “Applicant_Name_PlimptonPoorvuPrize2024”:

- Coversheet listing the following information:

- 2024–2025 Plimpton-Poorvu Design Prize Application

- Applicant Name

- Degree Program

- Graduation Date

- GSD Email Address and Permanent Email Address

- Course Number and Title in Which the Work Was Submitted

- Written Statement that describes the project and demonstrates the project’s feasibility in design, construction, economics, and fulfillment of market and user needs (1 page, approximately 300 words). If any aspect of collaborative work is submitted by an individual, the authorship of the work should be clearly identified and distinguished from that of the applicant. Projects performed as independent studies outside the GSD or as part of a professional commission will not be eligible.

- Visual Representation of up to 15 pages to supplement the written description (8.5×11 inch format) Note: Hardcopy, CDs, slides, loose materials, or physical models will not be accepted. All files must be uploaded to the OneDrive File Upload Link.

Notification of Recipients

The prize recipient will be announced at the GSD Awards and Diploma Ceremony as part of Commencement in May.

Eligibility

The Plimpton-Poorvu Design Prize encourages collaborative and cross-disciplinary work. The prize is awarded to an individual or team whose project, completed as part of their GSD curriculum, best demonstrates feasibility in design and construction and fulfills market and user needs.

Specifically, the jury looks for development proposals that use innovative design strategies to solve a problem, address a need, or serve a demand in ways that demonstrate a plausible path to implementation. Demonstration of feasibility may include a market analysis, business plan, and project pro forma.

Teams must have at least one GSD student and may include students from across Harvard and other universities. First, second, and sometimes honorable mention prizes are awarded to projects in amounts up to $20K.

Course work completed during the Spring 2024 and Fall 2024 semesters is eligible for the 2024-25 review cycle. A committee comprised of faculty members from each department will select a shortlist of candidates who will participate in a review and then be asked to submit a revised application, incorporating feedback from the conversation, in March 2025. The faculty committee, department chairs, and dean will review the revised submissions and select the prize recipients in April 2025.

Peter Rice Prize

Peter Rice Prize

The Peter Rice Prize is currently closed for submissions.

Please check back in Spring 2026 for updated information.

This prize was established in 1993 in recognition of the ideals and principles represented by the late, eminent engineer Peter Rice. The prize honors students of exceptional promise in the school’s architecture and advanced degree programs who have proven their competence and innovation in advancing architecture and structural engineering. Students should explain the contribution of the submitted work to advanced engineering and innovation in design.

Find out more about the history of the prize on the GSD Peter Rice Prize webpage.

See below for submission details.

Eligibility

Currently enrolled students in all GSD programs are eligible to apply.

You may submit one or more projects to be considered for this award. While the same project may be submitted for both Peter Rice and Digital Design awards, each package must be individually submitted and tailored to each award.

Winner Deliverables

No deliverable is expected from the recipient

Notification of Recipients

Prize recipients will be announced at the GSD Awards and Diploma Ceremony as part of Commencement 2025.

How to Apply

Submissions must include the following three components (all uploads will automatically add your name to the file when submitted so there is no need for you to add it to the file names):

1. A cover letter with each prize submission. This must be submitted as a separate file to SharePoint. It must include the following information:

- Your first and last names

- Your program

- Your graduation year

- Your email addresses (both GSD and personal)

- Indicate if it is an individual or joint project submission; if joint, include full names, program and graduation year of all collaborators

- Your project’s title

- Prize you want your project to be considered for (Peter Rice Prize)

- Indicate how you are submitting your work (all files via SharePoint file upload link, project files entirely on web and cover letter and statement via SharePoint file upload link, project files partially on web and rest via SharePoint file upload link)

- Label as follows: ProjectTitle_PRP_CoverLetter

2. A written statement (up to 600 words) with each prize submission. This must be submitted as a separate file to the SharePoint file upload link even if the rest of your project is viewable on a website.

- Label as follows: ProjectTitle_PRP_Statement

3. Your project files, either via SharePoint file upload link, project entirely on web, or project partially on web and rest via SharePoint file upload link.

- Label as follows:

- ProjectTitle_PRP_1ofX (X is the total number of project files you are uploading)

- ProjectTitle_PRP_2ofX (X is the total number of project files you are uploading)

- ProjectTitle_PRP_3ofX (X is the total number of project files you are uploading)

Evaluation Criteria

The written statement and project should prove competence and innovation in advancing architecture and structural engineering. The contribution of the submitted work to advanced engineering and innovation in design should also be explained.

Questions?

Contact Selena Shabot at [email protected].

For more information about the award, please visit the Peter Rice Prize overview page on the GSD’s website.

Digital Design Prize

Digital Design Prize

The Digital Design Prize is currently closed for submissions.

Please check back in Spring 2026 for updated information.

This prize is awarded annually for the most creative and rigorous use of computation in relation to the design professions. Students should submit projects that advance our understanding and demonstrate the use of digital media in design. Ordinary uses of digital media, or projects that use digital media merely as the choice of representation should not be submitted. Submitted project(s) should be innovative, push the envelope and provide new paradigms. Students should also explain their approach to digital media as demonstrated by the submitted project(s).

Find out more about the history of the prize on the GSD Digital Design Prize webpage.

See below for submission details.

Eligibility

Currently enrolled students in all GSD programs are eligible to apply.

You may submit one or more projects to be considered for this award. While the same project may be submitted for both Peter Rice and Digital Design awards, each package must be individually submitted and tailored to each award.

Winner Deliverables

No deliverable is expected from the recipient

Notification of Recipients

Prize recipients will be announced at the GSD Awards and Diploma Ceremony as part of Commencement 2025.

How to Apply

Submissions must include the following three components (all uploads will automatically add your name to the file when submitted so there is no need for you to add it to the file names) :

1. A cover letter with each prize submission. This must be submitted as a separate file to the SharePoint folder. It must include the following information:

- Your first and last names

- Your program

- Your graduation year

- Your email addresses (both GSD and personal)

- Indicate if it is an individual or joint project submission; if joint, include full names, program and graduation year information of all collaborators

- Your project’s title

- Prize you want your project to be considered for (Digital Design Prize)

- Indicate how you are submitting your work (all files via SharePoint file upload link, project files entirely on web and cover letter and statement via SharePoint file upload link, project files partially on web and rest via SharePoint file upload link)

- Label as follows: ProjectTitle_DDP_CoverLetter

2. A written statement (up to 600 words) with each prize submission. This must be submitted as a separate file to the SharePoint file upload link even if the rest of your project is viewable on a website.

- Label as follows: ProjectTitle_DDP_Statement

3. Your project files, either via SharePoint file upload link, project entirely on web, or project partially on web and rest via SharePoint file upload link.

- Label as follows:

- ProjectTitle_DDP_1ofX (X is the total number of project files you are uploading)

- ProjectTitle_DDP_2ofX (X is the total number of project files you are uploading)

- ProjectTitle_DDP_3ofX (X is the total number of project files you are uploading)

Evaluation Criteria

Submitted projects will be evaluated on innovation, whether the project goes beyond normal limits or ideas, and if it provides new paradigms that advance our understanding and demonstrate the use of digital media in design.

For more information about the award, please visit the Digital Design Prize overview page on the GSD’s website.

Questions?

Contact Selena Shabot at [email protected].

Peter Walker and Partners Fellowship

Peter Walker and Partners Fellowship

Eligibility

Recipients must be a graduating student in the Landscape Architecture program.

Winner Deliverables

The Fellowship must be used within two years of receipt of award. The fellow is expected to deliver a lecture, participate in a symposium, or another event to share their travel research with the GSD community.

Notification of Recipients

The prize recipient will be announced at the GSD Awards and Diploma Ceremony as part of Commencement in May.

How to Apply

There is no application process.

Evaluation Criteria

During the final degree vote meeting of the academic year, any member of the Faculty of the Department of Landscape Architecture may nominate a graduating student for the Prize. A discussion of the merits of the nominees will ensue, and the faculty vote to select one student from those nominated, “based on accomplishment in landscape design” to support travel that extends the learning experience of the formal educational program.

Questions?

Contact Briana King at [email protected]

For more information about the award, please visit the Peter Walker and Partners Fellowship overview page.

Penny White Project Fund

Hours

Mon-Fri: 9a.m.–5p.m.

The Penny White Project Fund is now closed to applications. Please check back in the Fall.

About

Project proposals are due in the early Spring semester. A Selection Committee will meet following the submission of proposals, and winners are notified and announced before Spring Break. A final report of the completed project must be submitted to the Department of Landscape Architecture by September of the same year.

Fund overview and objectives are available on the Penny White Project Fund webpage.

Evaluation Criteria

Proposals are evaluated by the Selection Committee on several criteria, including:

- Quality and clarity of the project

- Originality of research

- Feasibility of the budget and schedule

- Relevance to the Fund’s objectives

- Nature of the outcome

- Contribution to the field of landscape architecture

The Committee will pay special attention to the:

- Focus and quality of the proposals

- Relationship project objectives and proposed travel (if applicable)

- Relevance to the field of landscape architecture

The Fund welcomes projects that promote research at the intersection of systemic inequity and social and environmental justice, and that focus on the advancement of the political agency of landscape architecture as an activist, collaborative, and participatory practice.

How to Apply

Applications consist of a CV, project proposal, budget, literature and references, and optional visual material. Requirements for each component are listed below. All materials must be submitted via online application form . Late or incomplete proposals will not be considered.

It is strongly recommended that, in the preparation of their proposals, applicants consult Scholarly Pursuits: A Guide to Professional Development during the Graduate Years by Cynthia Verba. The guide offers valuable recommendations on how to: construct and polish arguments in the development of a grant application; write an abstract; and compose the general organization of ideas.

Curriculum Vitae

Applicant(s) must submit a maximum 2-page CV outlining their education, experience, and other relevant background to demonstrate capability and responsibility. For proposals developed by teams, each student should include an individual 2-page CV.

Project Proposal

Suggested maximum of 500 words.

Abstract

A brief of the main objective and scope of the project, including proposed method, and expected outcome. The abstract should clearly identify if the project is a case study, site investigation, a prototypical experiment, or any other form of research.

Project Description

A clear and comprehensive description of the project, its objectives, main tasks and outcomes. The description includes conditions addressed, questions asked, or hypotheses tested. The description must also describe if a similar project of this type has been done before, how it is different, what is aims to accomplish, and what is the substantive contribution to the field of landscape.

Project Background

A succinct outline of the project’s specific spatial, ecological and geographic context. The project background should also outline the historic, theoretical, scientific, representational, or practical discourse of the project, in relation to research and design in landscape architecture. Background information should be supported by relevant sources which might include reference literature, case studies, precedents, past projects. Clear and concise graphic illustration of the project background is encouraged.

Project Methods

A short explanation that describes the method that will be used to accomplish the main project tasks. In this section, precedents, historic case studies, earlier work with methods like those suggested in the proposal may be cited and will be used to clearly frame the discourse and the type of project in question. The project might be also identified in this section with specific modes of landscape architecture practice. The methods section should also describe if travel is essential for the coherent development of the research project and why.

Additional Resources for Project Methods:

- The Landscape Architectural Research: Inquiry, Strategy, Design by M. Elen Deming and Simon Swaffield (2010) is a helpful guide regarding research methods in landscape architecture.

- In cases involving human subjects, the research needs to be guided by the ethical principles set forth in the Belmont Report, which seeks the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. For research projects that deal with human subjects, it is strongly recommended that awarded students send their proposal to Harvard’s Committee on the Use of Human Subjects for revision. Visit the Committee on the Use of Human Subjects page for more information.

Project Schedule and Itinerary

A detailed description of the project timetable, start and end dates, timeline for main tasks, travel itinerary (if applicable) and sequence of deliverables. Please note that reasonable time must be dedicated to advance the definition of the project itself, to the preparation of the logistics of the trip (if applicable), and to the completion of the deliverables. If traveling, you may consider including a map of the area in which the project is to be developed, particularly if there are specific itineraries within the area that would help the committee understand the nature of your trip.

Anticipated Outcomes and Project Documentation

A description of tangible benefits, findings, and contributions of the project to the discipline of landscape architecture and fields of design. Provide a definition of actual outcomes (a conference, a paper, a map, a presentation, an interview, an installation) with relevant dates, as applicable. Outcomes and deliverables must be tangible, substantive, and feasible.

Project Budget

A detailed itemization of all anticipated expenses including:

- Travel (air and ground travel)

- Accommodations (hotel)

- Equipment and Resources (supplies, fuel, power, documentation, reproduction, copy)

- Incidentals (security, visa, guide, translation)

Although expenses for food and normal per diem costs are not covered by the Fund, project budgeting must demonstrate a clear understanding of project expenses and regional incidentals. The budget should not underestimate costs that might adversely affect the outcomes of the project. Any additional funding sources from other grant agencies must be disclosed.

Any equipment purchased with the funds remains the property of the Harvard University Graduate School of Design and must be returned to the Department of Landscape Architecture upon completion of the project.

Literature and References

A brief list of references, books, websites from preliminary research that demonstrates knowledge of the project discourse, area, and scope.

Visual Materials (optional)

Additional graphic material in the form of maps and diagrams may be provided to support the project proposal. All project imaging should be high resolution, with captions and sources.

Please include all visual materials in one document.

Project Advisors

Provide names and emails for two project advisors, including an Internal Faculty Advisor from the GSD, and an External Project Advisor related to the project tasks. Advisors will be contacted during the Selection Process.

The Internal Faculty Advisor may not be a current member of the Selection Committee.

Notification of Recipients

Recipients of the Penny White Project Fund will be notified by email and announced to the GSD by mid Spring semester.

Winner Deliverables

Final reports are due on September 22, 2025. Awardees must submit both a hard copy and a digital copy of their final report to:

Department of Landscape Architecture

48 Quincy Street, Room 409

Cambridge, MA 02138

One-fourth of awarded funds will be held back and released upon submission of the final report.

The Final Report should consist of the following contents compiled:

- Revised Project Summary: summary of the main objectives and scope of the investigation, the method and approach that has been followed, the learnings and outcomes (1 page)

- Revised Project Description: elaborated, clear, and comprehensive description of the project, also looking at the main objectives and scope, method and approach, learnings and outcomes of the investigation as it occurred during the research process (1-2 pages)

- Revised Schedule and Itinerary: include maps of the itinerary followed, and the research conducted and tasks accomplished in each phase of the schedule and location in the itinerary

- Project Images: between 5-10 photographs, maps, or diagrams

- Project Photography: 5-10 site photographs

- Learning Outcomes: What has been learned? What was initially expected and what was actually found? How did the project evolve during the preparation of the field work, during the trip, and afterwards? How has this opportunity impacted your understanding of design as a form of research? (1-2 pages)

- Conclusions: explain your conclusions, both partial and general, and whether, why, and if/how this project will be continued (1-2 pages)

Eligibility

All students enrolled in the Harvard Graduate School of Design are eligible to submit project proposals that address the objectives of the Penny White Project Fund. Although all GSD students are eligible, according to the Fund terms: “…it is expected that preference will be given to students in the Department of Landscape Architecture.” The Committee looks favorably upon collaboration between students in Landscape Architecture with other design disciplines. Only one grant may be awarded per student, either individually or in a group.

Travel Risk Rating

Prior to submitting an application, please carefully review the travel Risk Ratings provided by Harvard Global Support Services and the U.S. Department of State – Bureau of Consular Affairs . Travel to risk level 4 locations will not be considered. Travel to risk level 3 locations will be considered on a case-by-case basis. You will be asked to report your itinerary’s risk level(s) in your application.

Joint Applicants

Students may work individually or in teams, and in conjunction with or independently from their coursework. Collaboration with students that have already received an award from the Penny White Project Fund is not allowed.

Final Year Students

The Fund accepts proposals from GSD students currently in their final year, with conditions. Final-year applicants will be required to explain in their proposals the very specific dates in which they plan to travel or develop other activities associated with their research, how they plan to complete the project beyond graduation, and how they plan to report and submit their work by the deadline.

Questions?

Contact Rebecca Hallowell at [email protected]

For more information about the award including a list of past recipients, please visit the Penny White Project Fund overview page on the GSD’s website.

Norman T. Newton Prize

Eligibility

Recipients must be a graduating student in the Landscape Architecture program.

Winner Deliverables

No deliverable is expected from the recipient.

Notification of Recipients

The prize recipient will be announced at the GSD Awards and Diploma Ceremony as part of Commencement in May.

How to Apply

There is no application process.

Evaluation Criteria

A faculty committee chooses one student “whose work best exemplifies achievement in design expression as realized in any medium.”

Questions?

Contact Briana King at [email protected]

For more information about the award, please visit the Norman T. Newton Prize overview page.

Landscape Architecture Thesis Prize

Landscape Architecture Thesis Prize

Eligibility

Recipients must be a graduating student in the Landscape Architecture program who presented an independent thesis.

Winner Deliverables

No deliverable is expected from the recipient.

Notification of Recipients

The prize recipient will be announced at the GSD Awards and Diploma Ceremony as part of Commencement in May.

How to Apply

There is no application process.

Evaluation Criteria

Faculty and advisors submit nominations for this award. A faculty committee chooses one or more students from the Landscape Architecture program “who has presented exemplary thesis work.”

Questions?

Contact Briana King at [email protected]

For more information about the award, please visit the Landscape Architecture Thesis Prize overview page.