Coupling Thermal Mass & Buoyancy for Thermoregulation and Ventilation in India

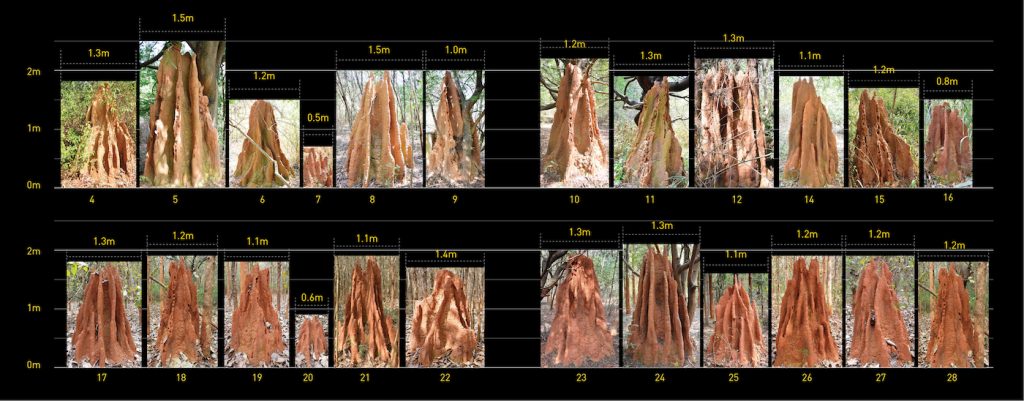

Termite mound, National Center for Biological Sciences, Bangalore, India

by Palak Gadodia (MDes ’16)

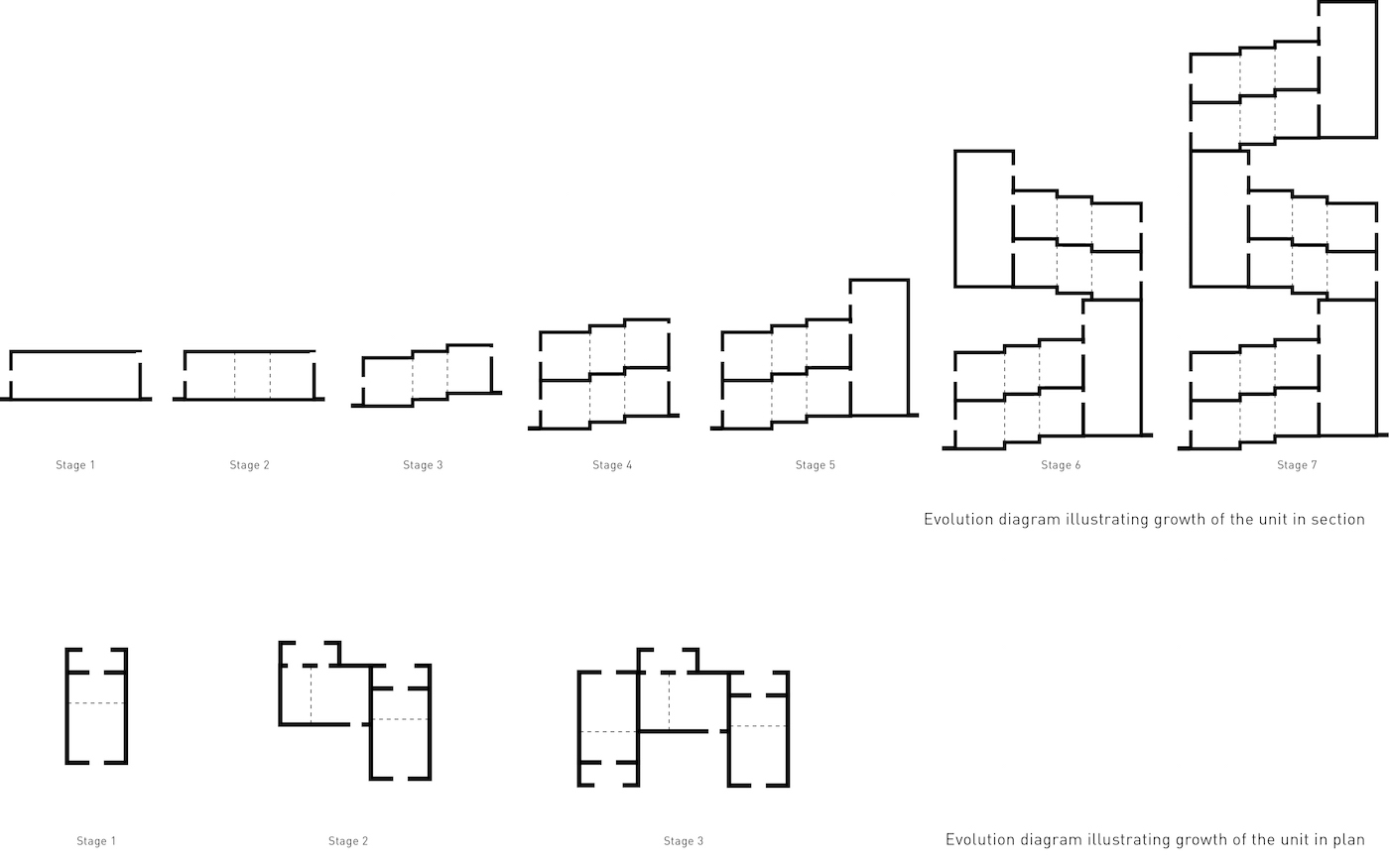

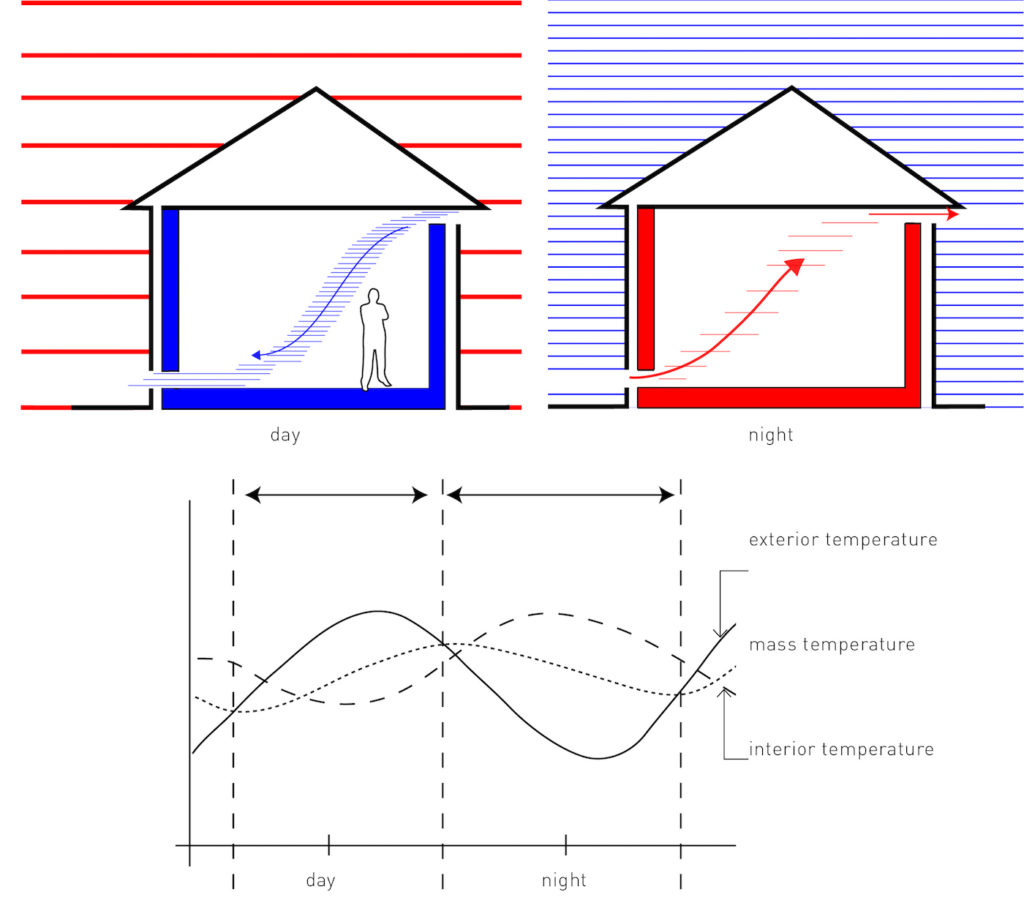

This thesis explores how the form and mass of a building can be ‘morphed’ to control interior temperature and fresh air flow. The idea is to couple thermal mass with buoyancy ventilation.

Using the ‘thermal resonator’ design method , and by studying how termite mounds extract useful work from exterior temperature oscillations , the project shows how new buildings in hot climates can be designed resiliently to avoid the use of HVAC technology.

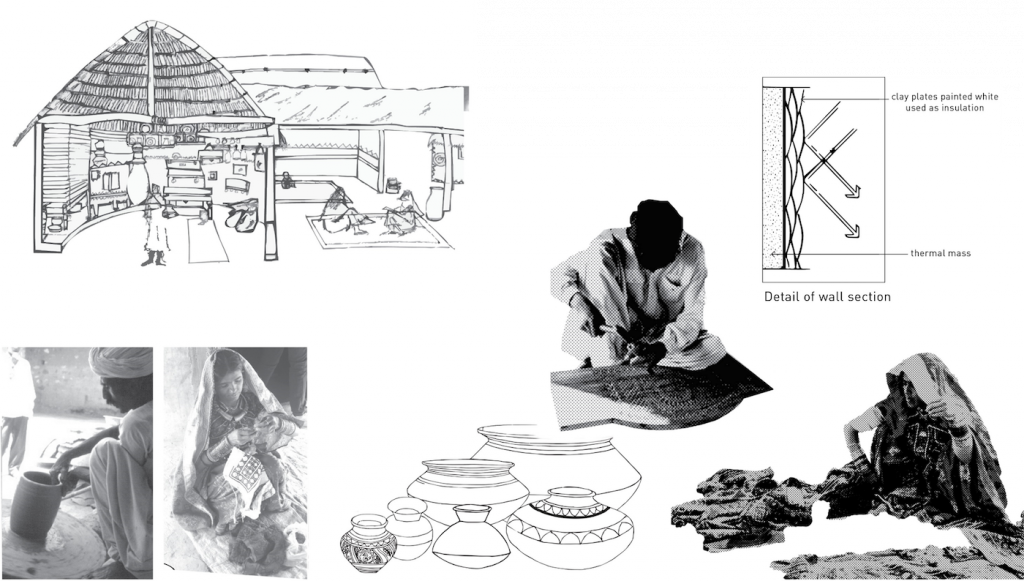

First, a review of traditional and contemporary uses of thermal mass and buoyancy ventilation was undertaken. It turns out that there are very few examples where the thermal mass controls the fresh air flow, on top of interior temperatures.

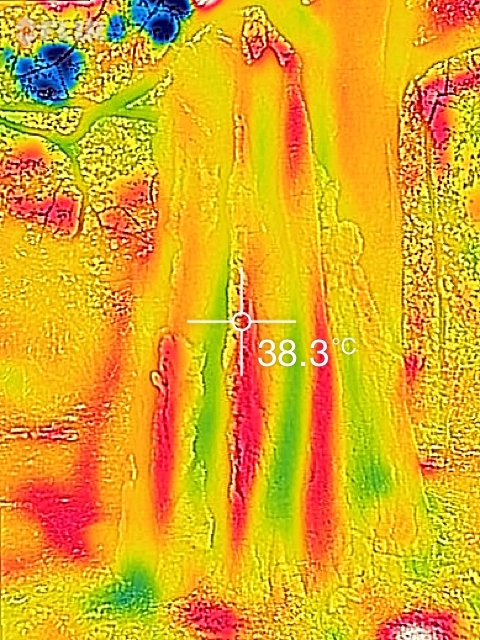

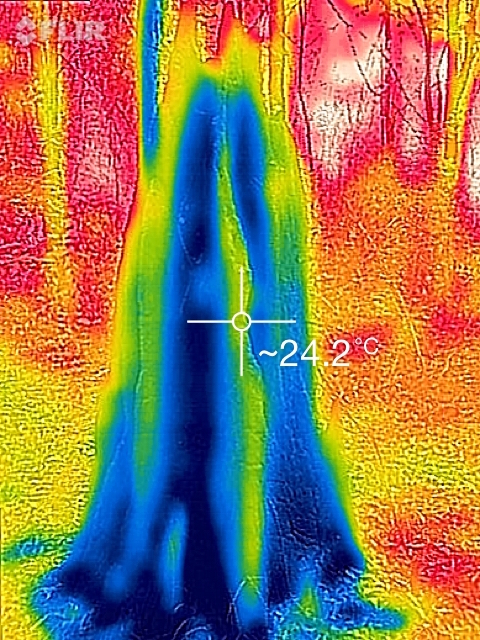

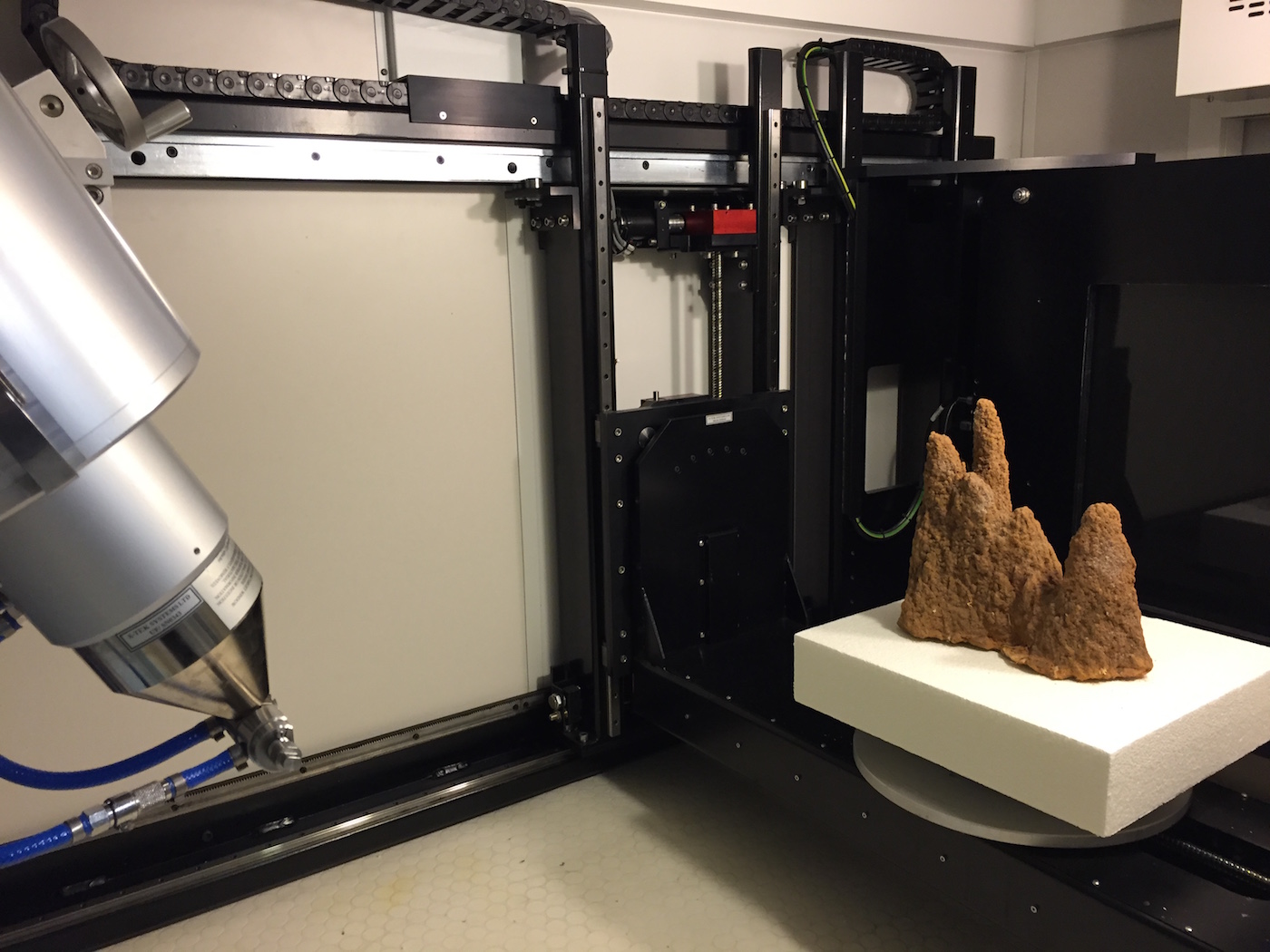

Second, a close reading of a recent study on thermoregulation in termite mounds in Bangalore was made, to understand how the geometry and materiality of the mounds regulate the interior temperature and the exhaust of stale air. General measurements of termite mounds in Bangalore, and detailed measurements of a top-cone sample taken from a dead mound was documented.

Third, the ‘thermal resonator’ design method was reviewed, and used to develop climate performance indices. A systematic analysis of climate zones in India was undertaken, with reference to key demographic data, and information on local building traditions, to understand where in India it makes most sense to design these kind of ‘mass-only’, HVAC-free buildings.

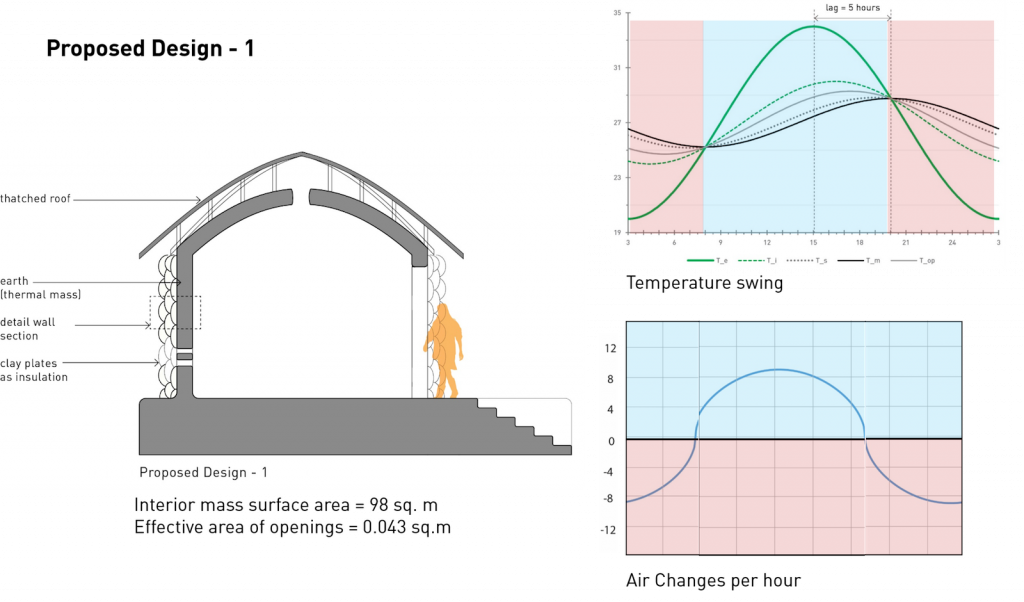

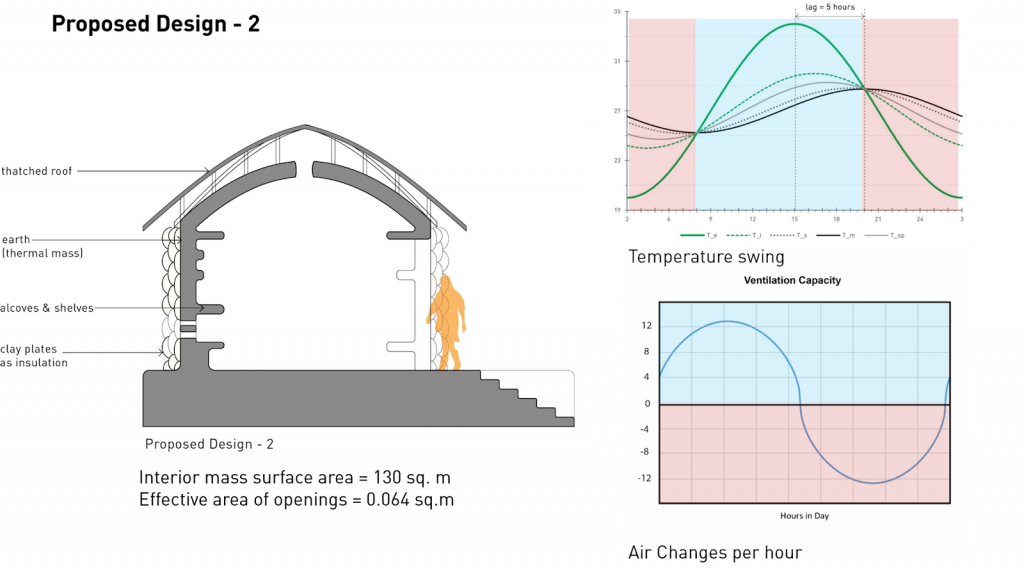

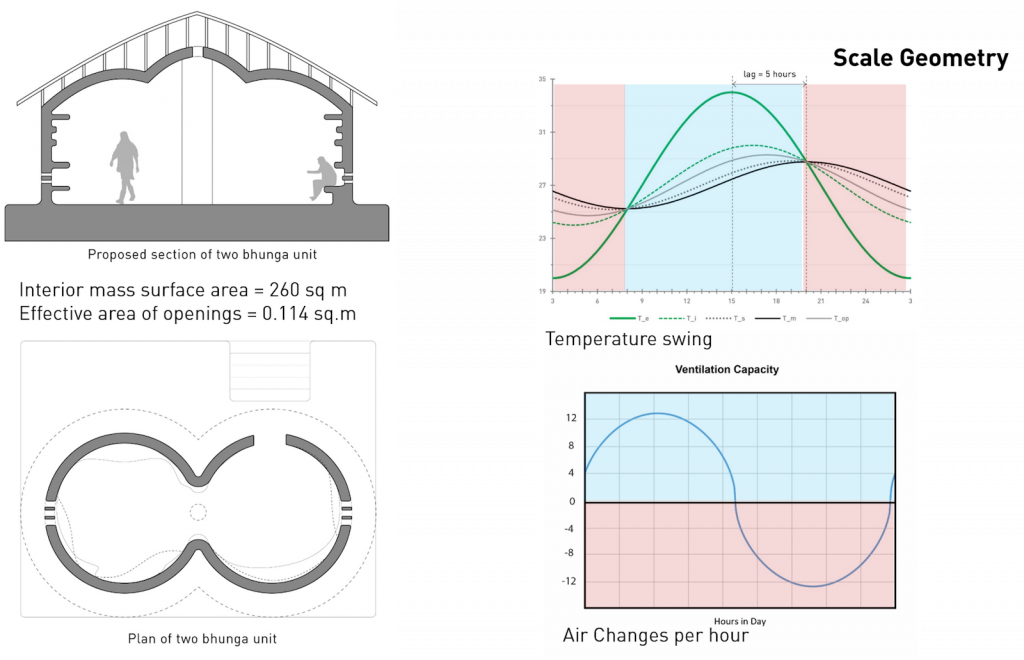

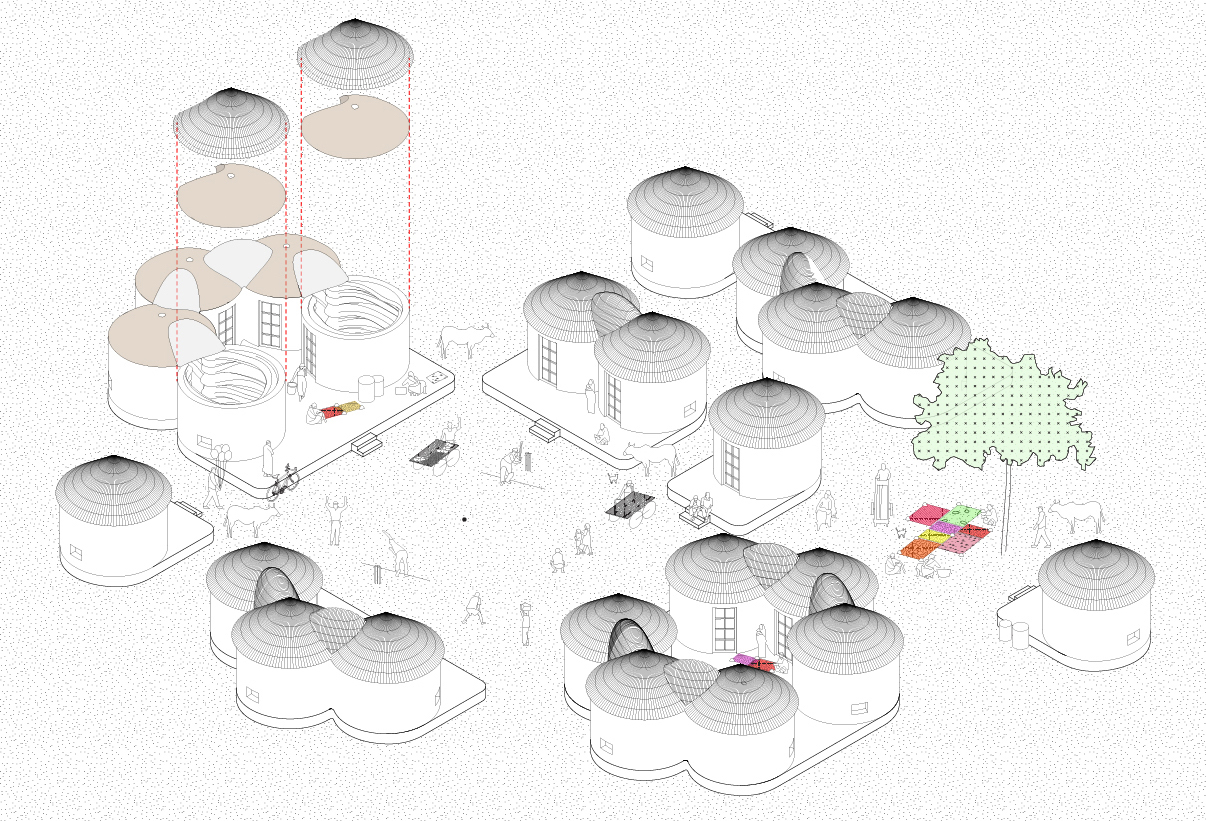

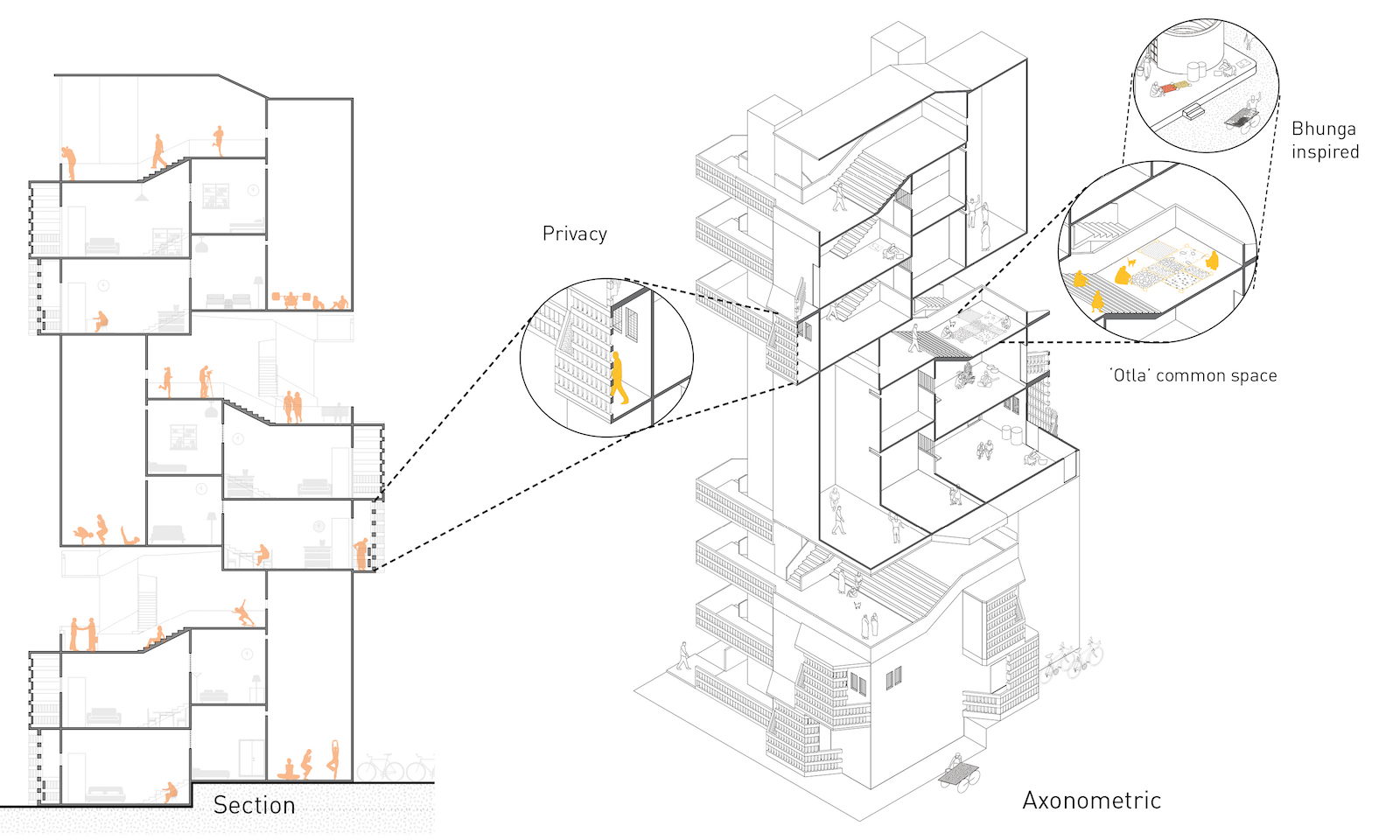

Fourth, traditional and contemporary building practices in India was evaluated, paying close attention to the use of ‘massive’ materials such as adobe, rammed earth, brick and concrete, and how these buildings might be ‘morphed’ to have the thermal mass control interior temperature and ventilation air-changes was shown.

Fifth, an experimental study was undertaken, to show how the thermal exchange capacity of massive elements, such as rammed earth walls or concrete soffits, could be increased by changing the morphology of the surface.

Finally, the project comments on the limitations of the “thermal resonator” method, and the different ways it might be applied in other areas of the world.