Urban Intermedia

“Urban Intermedia” argues that the complexity of contemporary urban societies and environments makes communication and collaboration across professional boundaries and academic disciplines essential. Each discipline produces its own forms of knowledge, but also has “blind spots” that can only be approached through other disciplinary frameworks. Those blind spots are the focus of the research and exhibition. Four city-based research projects in Berlin, Boston, Istanbul, and Mumbai form the core of the project and exhibition.

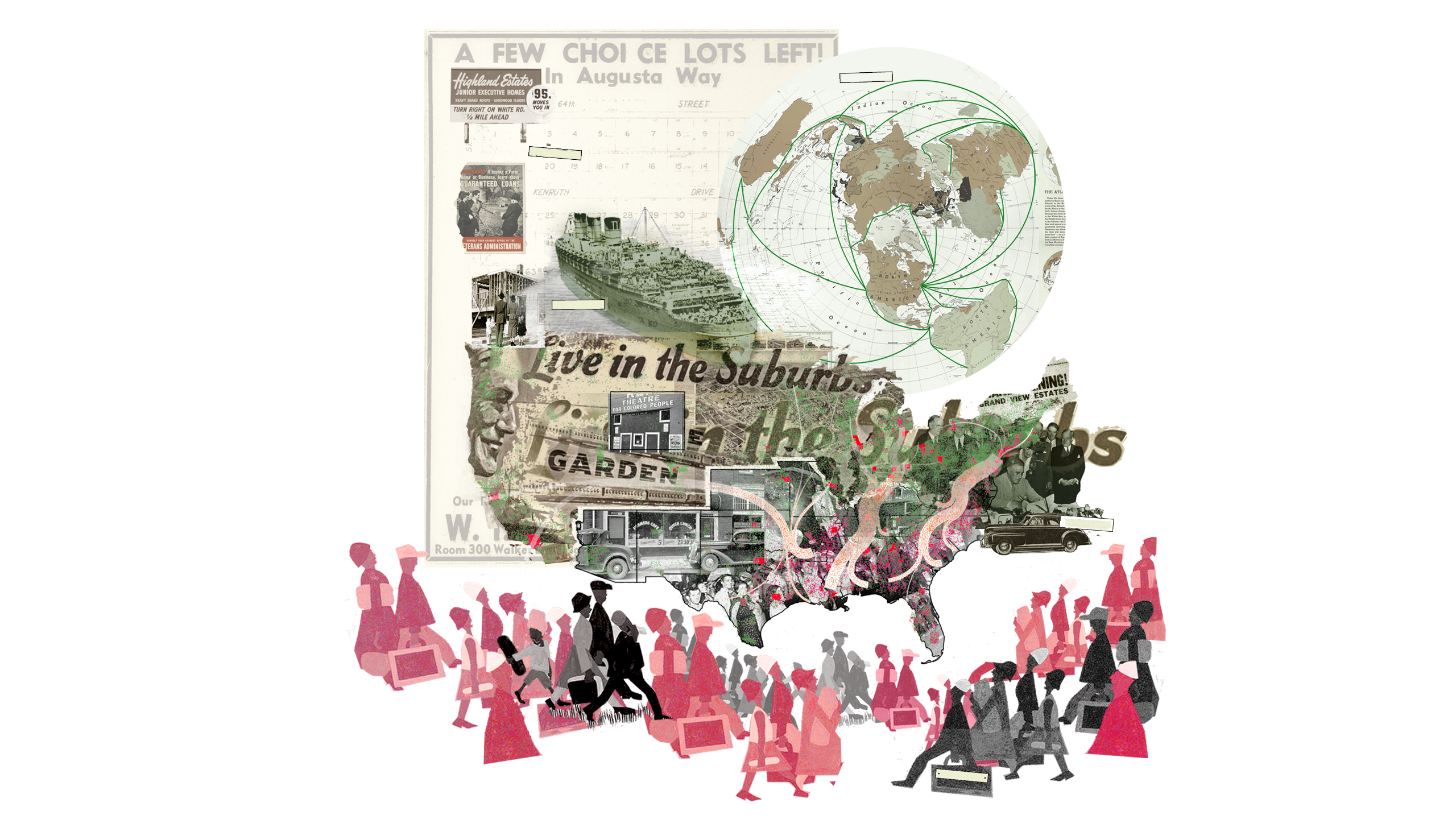

The theme for the Boston portal is “Race and Space”: cautionary tales about systemic racism. In the United States, urban projects emerge from collisions of competing interests and struggles over power and space, but also from racialized policies and exclusionary practices. In the urbanization of Boston, racism has been a persistent, yet insufficiently addressed phenomenon dominated by two recurring themes: pervasive racism toward communities not considered “white” (native Americans, black Americans, and most post-Puritan immigrants at various points in time), and tireless resistance to racism through community organizing and civil disobedience.

Between 1950 and 1980, federally funded highway and urban renewal projects swept through U.S. cities. National programs that promised to connect and rebuild crumbling urban cores instead systematically dismantled them, in the process disproportionately harming immigrants and people of color. These programs were designed primarily to respond to urban neglect following two post–World War II migratory movements. First, “white flight” saw white Americans moving to the suburbs, motivated by the promise of a better life and fueled by federally insured mortgage lending that chiefly benefited white veterans and steered them away from “red-lined” inner-city neighborhoods, which were predominantly black. Second, there was a mid–20th-century peak in the Great Migration of black Americans moving north and west to escape the Jim Crow laws of the Deep South and pursue economic opportunity. Many settled in segregated inner-city neighborhoods and, in Boston, were concentrated in a wedge-shaped area of the city where many black Americans and immigrants still live, experiencing dramatic disparities in wealth, educational attainment, and life expectancy as well as below-average access to jobs, open space, and public transportation.

While disparities caused by systemic racism are unambiguous in Boston, open discussion of the subject has only recently become a part of mainstream public discourse. The research presented here is intended to contribute to that discourse. It spans three eras of city-making and focuses on three physical infrastructures that define the spatial and political dimensions of the “wedge.”

“South Bay: Land-Making and Shifting Demographics” explores the interrelationship of migration and mobility in the shared histories of land-making, industrialization, mobilization, and immigration at South Bay, connecting industrial growth to immigrant influx and the early roots of Boston’s racist past. At the beginning of the 19th century, Boston embarked on a land-making campaign to support growing industries and meet housing demands. By the mid-20th century, the land area of the Shawmut Peninsula (home to the greater Boston metropolis) had increased 400 percent. In South Bay, the transformation was an incremental layering of shipping, rail, and highway infrastructures, and industry and housing fluctuated between serving two groups: working class immigrants and minorities, and predominantly white middle-class “Yankees” and “Yuppies.” This research exposes Boston’s manifestly limited progress in combating the effects of systemic racism over 150 years of housing development around South Bay.

“Southwest Corridor Park: Infrastructure and Community Power” explores the planned and unplanned impacts of racially insensitive public policies, community resistance to those policies, and remedial actions taken in the making and mending of Southwest Corridor Park. Federal highway expansion projects of the mid-20th century ripped through minority and immigrant communities across the country. In Boston, an Inner Belt connector was planned as the last remaining section of Interstate Highway 95, which would connect Florida to Maine (and, locally, Boston to Cambridge and Somerville). The project was ultimately halted by multi-city community action, but not before six miles of the neighborhood were demolished. Today, the Park is a reminder that celebrated urban infrastructures—including community gardens, playgrounds, bike paths, and subway lines—do not automatically improve the well-being of communities, especially if those communities are not true partners in their making.

“Columbia Road: Big Plans and Social Tensions” tracks nature and technology as oscillating drivers for urban growth. In the late 19th century, Frederick Law Olmsted championed an era of U.S. city planning aimed at mitigating the “harmful effects” of industrialization through park infrastructure. Boston’s most iconic public infrastructure, the Emerald Necklace, was designed to improve public health, support social cohesion, and drive market investment. But the Columbia Road section of the plan was never finished. With the city’s renewed commitment to completing Olmsted’s Necklace, the question today is, “Will Boston seize the opportunity presented by the Columbia Road project to empower communities, promote equity, and combat systemic racism through truly collaborative action?”

For more information about the Harvard Mellon Urban Initiative, please visit mellonurbanism.harvard.edu.

View the Animated Narratives.