In June 1648, a Puritan midwife named Margaret Jones was executed by hanging from an elm tree in Charlestown, Massachusetts. The reason, as recounted by the governor of the colony at the time, John Winthrop, was that she was a healer. “She practi[ced] physic,” he wrote in his journal, “and her medicines being such things as, by her own confession, were harmless—as anise-seed, liquors, etc.,—yet had extraordinary violent effects.”

Perhaps even more alarming to her accusers, it seems, was Jones’ confidence in her own medical judgment. “She would use to tell such as would not make use of her physic,” Winthrop continues, “that they would never be healed; and accordingly their diseases and hurts continued, with relapse against the ordinary course, and beyond the apprehension of all physicians and surgeons.”

That a woman was put to death because she was practicing what amounts to 17th-century allopathic medicine is shocking when seen through a contemporary lens. For centuries before Jones’ horrific end, though, women dedicated to the healing arts had been targeted by witch hunts throughout Europe. In fact, an edict from the Catholic Church in 1322 unequivocally stated, “If a woman dare to cure without having studied she is a witch and must die.” Since no women were allowed to study medicine at the time, this meant that all female healers, herbalists, and midwives took their lives in their own hands every time they dared alleviate the suffering of their mostly female peasant patients.

The fact that Jones was executed a little more than three miles from what is now Harvard’s Graduate School of Design is not lost on architect and activist Malkit Shoshan. Her exhibition Love in a Mist (and the Politics of Fertility) provides a trenchant exploration of the many ways in which the enduring struggle for control over women’s bodies that had such brutal expression in the witch hunts not only persists but is intertwined with the ongoing subjugation of the natural world. In other words, Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Shoshan took as her starting point the increasing number of threats to Roe v. Wade—including the so-called heartbeat bills that propose banning abortions once a fetal heartbeat is detected and the “domestic gag rule” on Title X family planning services that would effectively shut down the only means of birth control and pregnancy counseling to 4 million of the country’s most vulnerable women. For those who wonder what all this has to do with architecture and design, consider this: The domestic gag rule calls for the physical separation of clinics that offer family planning and those that offer abortions, in effect necessitating the building of off-site clinics—a prospect that is simply too expensive for most to consider.

“I figured out early in my studies how you could understand politics and policies through space,” says Shoshan, who has spent much of her professional life studying and mapping aspects of the territorial conflicts between Israel and Palestine. Love in a Mist is grounded in the feminist scholarship of Silvia Federici, whose recent book, Witches, Witch-hunting and Women, draws a direct parallel between the contemporary political war on women and the witch hunts of the past, and architect Lori Brown’s ongoing research into the highly contested space of abortion clinics. Shoshan conceived of an exhibition in which visitors would not only experience up close artifacts and documents from distant and recent histories concerning the control of female fertility but also evidence of the same being done to nature at large. Multisensory artworks provide intense experiences of these themes. Cleverly, the exhibition flows through a series of constructed “greenhouses”—those places, Shoshan says—“where you practice care and reconnect with nature—a space of intimacy and connection and regulation in a soft way.”

Shoshan conceived of an exhibition in which visitors would not only experience up close artifacts and documents from distant and recent histories concerning the control of female fertility but also evidence of the same being done to nature at large.

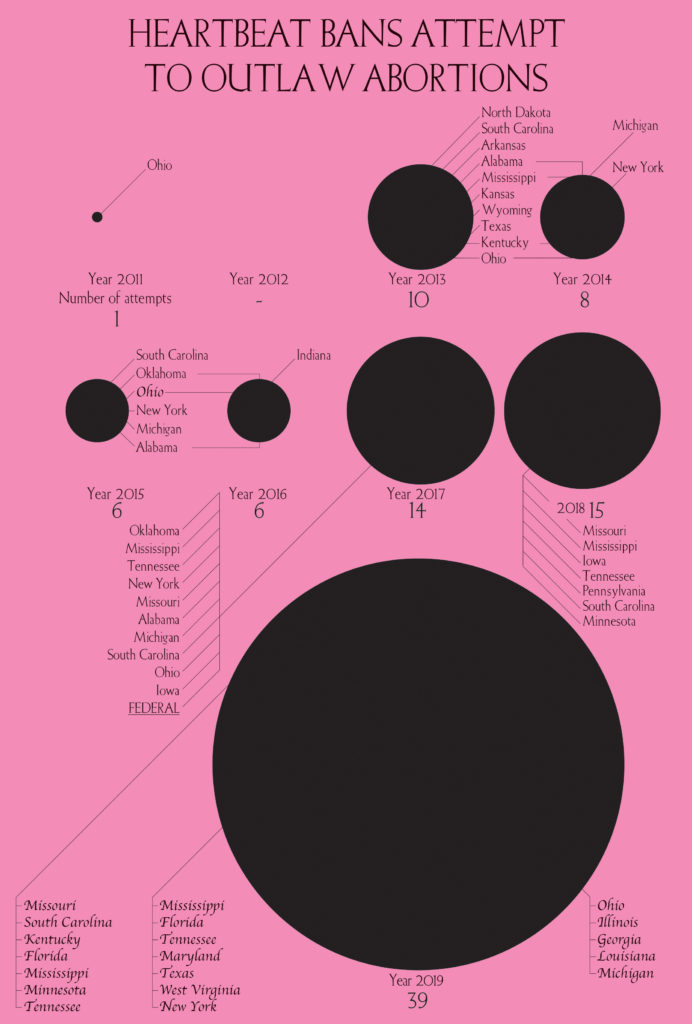

The exhibition takes its lyrical title from the name of a purple flowering bush used in folk tradition to regulate fertility. And perhaps not surprisingly, Shoshan’s first greenhouse is focused on the history of abortion. It includes an example of a recipe for an herbal potion that was thought to have been destroyed by the witch hunts but was rediscovered by medical historian John Riddle; graphics representing the explosion in attempts to outlaw abortion since 2011; and maps and essays by Lori Brown outlining the tremendous distances between clinics in Texas. There is also stunning documentation of the work of Rebecca Gomperts, the Dutch doctor and activist whose organization, Women on Waves, has brought the means of abortion to countries where it is outlawed. A-Portable—a container clinic for traditional abortions designed by Gomperts’ compatriot, artist Joep van Lieshout—is mounted on boats for use in international waters, and abortion pills have been delivered via drones. Gomperts’ work provides a bold and compelling counterpoint to those women who tragically lost their voice in history doing what amounts to the same thing.

By focusing on the acceleration—rather than the inhibition—of growth, the exhibition’s second greenhouse area explores the impact of 20th-century hormones and fertilizers on the female body and the natural world. Despite its much-touted benefit of improving the retention of pregnancies, for example, the synthetic estrogen diethylstilbestrol (or DES) proved not only to be ineffective but also harmful to the women who took it, as well as to their children. Although the FDA issued a bulletin to doctors in 1971 that linked prenatal DES prescriptions to a rare form of vaginal cancer, it did not withdraw actual approval of the drug until 2000. Even the US Department of Agriculture banned its use in 1979 as a growth stimulant in livestock. The dichotomy certainly gives the impression that the government cares more about cattle than women.

The blunt force trauma of such statistics are brought to life in Bodies on Steroids—a line-up of supersized blow-up animals, vegetables, and fruits that are sight gag and grotesquerie at the same time. Whether or not the future will bear such Brobdingnagian beasts, the message is clear: Anthropocene alteration of nature inevitably has its consequences, whether visible or invisible. The exhibition’s inclusion of several installations from “soundscape ecologist” Bernie Krause poignantly illustrates this point. By painstakingly recording landscapes around the world for decades—including near his home in Sonoma County, California—Krause has tracked the definitive silencing of what he calls nature’s “biophony,” not only with audible soundscapes but also with the graphic visualizations of sound. Through this compelling methodology, he shows, in Sounds of Extinction, how the purportedly sustainable practice of selective logging has had a devastating impact on local wildlife—even if the landscape looks virtually unchanged to the eye.

The unnatural growth of nature is a theme in Dutch artist Desirée Dolron’s stunning and eerie Uncertain. Her video installation focuses on a cypress swamp on the Texas/Louisiana border that is threatened by the hostile invasion of Salvinia, an aquatic plant imported from Brazil as aquarium flora that was mistakenly introduced into the Texas ecosystem in 1998. It is the perfect segue to the exhibition’s third greenhouse, which teases out the dire warnings of a landmark United Nations climate report released by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services this past May. The proliferation of invasive species turns out to be one of five major factors imperiling the one million animal and plant species facing possible extinction in upcoming decades due to human activity.

The endgame of unchecked Western economic growth is not progress and equity; it’s overdeveloped land and sea use, direct exploitation of organisms, climate change, pollution, and displaced species run amok. The bright spot in the report’s otherwise foreboding contents is the establishment of a task force that not only recognizes the wisdom of indigenous and local communities around the world but vows to include them in environmental governance efforts going forward. It’s a smart—if overdue—idea given that land managed by these communities is declining less rapidly than those overseen by industrialized populations.

The future, it turns out, will have to learn more from the past or else risk diminishment or even extinction. While the Margaret Joneses of the world are buried in time, perhaps their message of cultivating nature, self-sufficiency, and effective folk traditions are not. Love in a Mist concludes its compelling quest with a host of future imaginaries that propose alternatives to our current apocalyptic pathway.

The endgame of unchecked Western economic growth is not progress and equity; it’s overdeveloped land and sea use, direct exploitation of organisms, climate change, pollution, and displaced species run amok.

The final greenhouse begins with a neon sign that asks What if Women Ruled the World?—the title of Israeli artist Yael Bartana’s compelling stage performance, which intermingles an all-female cast with legislators, advocates, thinkers, and scientists in a Dr. Strangelove–reminiscent doomsday scenario. With two-and-a-half minutes to go on the doomsday clock, Bartana posits that perhaps only women can break from the patriarchal orthodoxy that has brought us to the brink of global disaster.

Franco-Guyanese-Danish artist Tabita Rezaire’s 21-minute video installation, Sugar Walls Teardom, continues the provocation with an exploration of the critical wounding of the womb—particularly for women of color. They have been used as guinea pigs to further white gynecological “progress”—evidenced by the “father of modern gynecology” James Marion Sims’ brutal experiments on unanesthetized slaves and Dr. George Gey’s surreptitious capture and cultivation of Henrietta Lacks’ cancer cells, now immortalized in the so-called HeLa line. Through her own particular form of “digital healing activism,” Rezaire proposes to decolonize the womb not only through calling attention to the past in her video but through swirling digital collages, empowerment slogans, energy work and, finally, a guided meditation meant for collective—not just individual—transformation.

Just a few steps past Rezaire’s video sits Joep van Lieshout’s larger-than-life sculpture of the female reproductive system, as if reborn from its history of trauma. Pink, fleshy, unapologetic, van Lieshout’s Womb seems to be the return of the repressed writ large and an elucidation of Rezaire’s proposition that “The womb is the original technology”—one with its own power and intelligence that is forever being poured into the world for the sake of the collective rather than amassed for personal gain.

Though Shoshan’s exhibition seems to end on a hopeful note, Desirée Dolron’s final work, Complex Systems, may just have the last word. A mesmerizing recreation of murmurations—the wheeling, gyrating swarming of thousands of starlings—Dolron’s digital depiction addresses the very question of the role of the individual within a collective. It simultaneously confronts the still mysterious wisdom of flock behavior in nature and the overwhelming menace of the political hive mind that has gotten us into our current political predicament. The fluttering of bird wings in Dolron’s affecting audio track seems matched by the incoherent mutterings of some infernal source. In the end, perhaps, it’s the very title of Shoshan’s show that best alludes to such polarity. After all, another name for the purple flowering love-in-a-mist is devil-in-a-bush.