Cities don’t close when mayors sign out of their email accounts and City Hall turns its lights off. As more and more urban residents spend more of their time in cities after dark and seek more expansive definitions of “nightlife”—and, as that nightlife increasingly extends beyond the urban bull’s-eye—a new type of “shadow mayor” is emerging in cities around the world, a liaison who serves as an advocate, mediator, policy-maker, and point-of-contact for a city’s nocturnal life.

These so-called “night mayors” represent a modern and hybrid role, intended to deliver urban governance and advocacy around the powerful and still-growing economic sector of nighttime activity. Night mayors’ purviews transcend bars and nightclubs to include restaurants, theaters, hotels, and creative spaces, as well as the night-shift workers who keep these operations functional and the Uber, taxi, and delivery drivers who keep products and services moving.

In short, night mayors guide policy and mediate relations around a city’s nocturnal vibrancy. It’s no small task, and one in increasing demand.

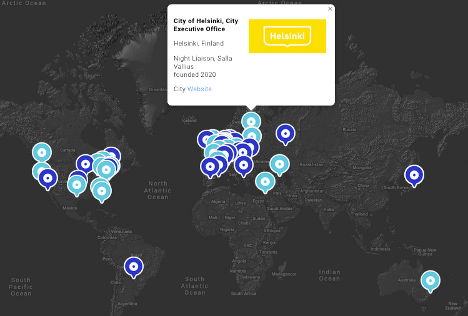

Given both the novelty and the fast propagation of the night mayor, Harvard Graduate School of Design Doctor of Design candidate Andreina Seijas embarked on a qualitative study that gathered data from 35 night mayors and night-time advocacy organizations from around the world. In January, the journal Urban Studies published results of Seijas’s study (co-authored by Mirik Milan Gelders), offering the first comprehensive analyses of the relevance of this new form of urban governance.

While the urban night has traditionally been relegated to strict policing and surveillance, and while cities differ greatly in their approach towards night-time infrastructure and regulation, a growing consensus has emerged around the need for permanent nocturnal governance structures.

Seijas found that, while the urban night has traditionally been relegated to strict policing and surveillance, and while cities differ greatly in their approach towards night-time infrastructure and regulation, a growing consensus has emerged around the need for permanent nocturnal governance structures.

By encouraging greater dialogue and experimentation, Seijas continues, these governance structures are challenging traditional approaches to urban authority and paving the way for a new wave of studies on the urban night. For instance, while most local authorities are organized spatially into wards, districts, or boroughs, night mayors respond instead to a “time-based” constituency, Seijas indicates—a framework that may help cohere city functions and infrastructure across neighborhoods and districts.

Today, more than 45 cities around the world have formally appointed “night mayors” to improve quality of life at night. Inspired by Amsterdam, the first city to create such a role, many other city governments have adopted this model to mediate between citizens who want to work, party, or sleep after dark.

“Nocturnal governance is not a one-size-fits-all approach, but a platform for cities to reexamine and handle new urban challenges,” Seijas says. Night mayors and night-time advocacy organizations proceed from their local political and regulatory structures, Seijas continues, which accounts for geographic differences in the way the role has been adopted: while European night mayors are independent advocates who help mediate between nightlife operators and citizens, their American counterparts—often titled as “managers” or “directors”—are government-appointed representatives responsible for overseeing their cities’ night-time economies.

A handful of cities in the United States, including New York, San Francisco, Seattle, Orlando, and Washington D.C., have introduced some form of the “night mayor” role: Pittsburgh and Orlando each have a “nighttime economy manager”; there’s a “nightlife business advocate” in Seattle and a “24-hour economy ambassador” in Detroit; New York and Washington, D.C. each have created a specialized “Office of Nightlife.”

Seijas observes a few shared motivations that have fueled the rise of the night mayor around the world. One dynamic at play is the disappearance of traditional nightlife venues, and the reduction of available creative space, resulting from factors including gentrification and the reconfiguration of certain neighborhoods into mixed-use areas; another is the need to create safer, more inclusive, and more dignified spaces for people of different preferences and social groups who are socially or professionally active after dark, and to provide support, training, and other resources for those who work at night.

As Seijas explains, the question of the “urban night” is a relatively new field of study. Investigations of cities’ nighttime functions have been growing since the 1990s, when revitalization strategies in post-industrial cities began using terms like “nighttime economy” and “24-hour city” as they worked to create more vibrant, safer, and more competitive environments regardless of time of day.

Seijas points, too, to three previous waves of study of the urban night, as categorized by British scholar Phil Hadfield. Hadfield surveyed studies that posited nightlife as a way to revitalize post-industrial city centers (a first wave of studies), as well as studies about the negative impacts and subsequent surveillance of nightlife (a second wave), followed by studies about new practices and mechanisms to manage life at night more proactively (third wave).

As the “night mayor” actor emerges, Seijas sees the potential for a fourth wave of urban-nightlife study, one that takes up how this specific form of nocturnal governance can influence urban authority more generally and provide new platforms to deal with both ongoing and unforeseen urban issues.

“Night mayors are the latest and, perhaps, the most exciting addition to a growing cast of actors involved in governing the city at night,” Seijas says. “Along with the police, neighborhood watches, Business Improvement Districts, and other groups, night mayors help keep streets safe and vibrant at night, but they do so from mediation rather than from regulation. While they are still are relatively new figure, and while their scope and influence vary significantly from city to city, night mayors’ visibility and journalistic appeal has helped situate the night in urban agendas and is raising awareness of the need for more research and experimentation in this largely unexplored time frame.”

Thus far, Seijas observes night mayors’ impacts have extended across policy-making, mediation, advocacy, and infrastructure- and capacity-building. Orlando’s “Night-Time Economy Manager” has been instrumental in encouraging public-private partnerships to improve safety and mobility in the city’s downtown entertainment district, Seijas notes, including introduction of a pilot program to create two rideshare hubs that help manage crowds efficiently and streamline transit downtown. Night mayors have become key mouthpieces for the LGBTQ+ community, she adds, leading World Pride celebrations and awareness efforts in cities like New York and London.

The night mayor is not always intended to amplify nightlife, though. Seijas points to cities like Prague, where the noční starosta or night mayor has led information campaigns to prevent people from drinking in the street and is encouraging the city to move away from its reputation as a party destination by promoting higher culture such as local museums and galleries. In Washington, D.C., the director of the Mayor’s Office of Nightlife and Culture is equipping nocturnal employees with tools and technology to handle recurring issues such as sexual harassment, drug use, and underage drinking, one effort to optimize police resources and encourage law enforcement as a last resort only. (While night mayors generally lack formal law-enforcement authority, their position as mediator between businesses and residents can free-up police and other law enforcement from routine noise and behavior complaints.)

The world’s ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has, without question, disturbed cities’ functioning, especially in terms of residents’ ability to make use of their cities’ offerings. During a crisis in which large crowds of people are a potential danger, nightlife, cultural offerings, and hospitality are some of the sectors most affected by lockdowns and restricted movement.

Despite this condition, or perhaps because of it, the role of a night mayor may actually emerge as more valuable than ever. The COVID-19 pandemic has raised or stoked questions about the way leisure and entertainment are distributed in urban areas. Most cities already have strict restrictions concerning the times and locations in which night-time activity can occur, segregating nightlife and entertainment to specialized districts with strict closing hours and surveillance; the further restrictions imposed by the current pandemic intensify questions and dilemmas around how to organize and govern nighttime activities.

Meanwhile, cities like Amsterdam have embarked on innovative experiments to enable greater flexibility in night-time regulations. Led by its Nachtburgemeester, or night mayor, the city introduced in 2013 a 24-hour-licensing pilot scheme that allowed establishments located outside of the highly saturated city center to operate around the clock. The initiative—which became a permanent program—has enabled the expansion of nightlife in a way that it is not disproportionately concentrated in a single area or time frame, helping reduce problematic crowding and decrease binge drinking in one of the most popular nightlife destinations in the world.

If implemented carefully, by conducting feasibility studies and trials, Seijas believes that similar schemes that allow new spatio-temporal distributions of nightlife and entertainment can be a useful tactic to help these sectors as well as cultural scenes bounce back from this unprecedented crisis.

As of May 2020, more than 45 cities around the world had appointed a “night mayor” or similar role to think more strategically about the urban night. While regional groups and partnerships dedicated to nighttime activities had already been in place, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought night mayors together creating a global platform to share ideas and best practices on how to manage the crisis at hand. Through WhatsApp chat groups, online seminars, and working papers, these individuals are currently discussing the feasibility of reopening local bars and restaurants, while considering future scenarios to help these businesses recover and adjust to the “new normal.”

“While it is too soon to tell the extent to which these actors will help manage the current crisis and its aftermath,” Seijas says, “these new nocturnal governance networks are already providing new spaces for cities to manage proactively one of the most devastating disasters of our time.”