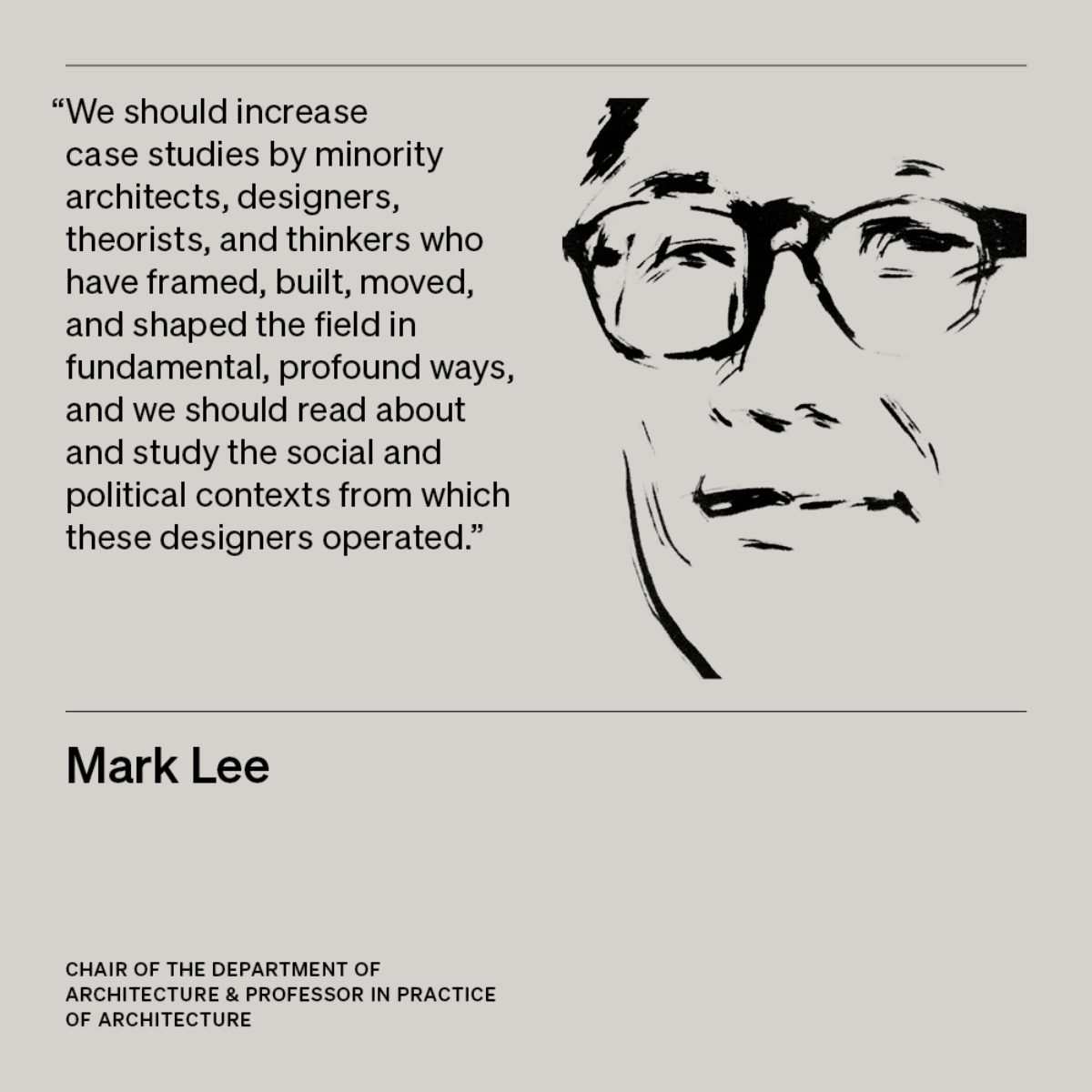

Mark Lee, Chair of the Department of Architecture & Professor in Practice of Architecture

What work needs to be done immediately to address the issues raised by the Notes on Credibility?

While there is a lot of work to be done over the long term, there are opportunities for the GSD and each of its departments to discuss and enact more immediate, action-specific, anti-racism changes, starting with our curriculum. We need to acknowledge the multiple cultures that have contributed to the field, but that have been overlooked or quieted. We should increase case studies by minority architects, designers, theorists, and thinkers who have framed, built, moved, and shaped the field in fundamental, profound ways, and we should read about and study the social and political contexts from which these designers operated. While broad, this shift in perspective can work to establish architecture as a canon that is not exclusively white, Eurocentric, or male. And of course, central to realizing any of these actions is hiring and supporting Black faculty. This will be a priority for me and the department in the coming years.

Within the Department of Architecture, our core and option studios need to do more to engage programs, sites, and typologies that provide vital services to cities and regions and that must be responsive and accessible to diverse groups—spaces like community centers, libraries, clinics, and schools, especially those in underserved communities. Such spaces are fundamental not only because they provide needed services, but because they demonstrate social hierarchies that facilitate justice and enable injustice. Engagement with the community could be instilled within the core pedagogy as an essential value in design.

My colleagues and I have a significant responsibility to listen. We need to take in these suggestions; reflect on how these shortcomings have been allowed to persist and on the inequities they have perpetuated; and be cognizant of how current teaching and discourse may be contributing to structural racism and to the erasure of diverse voices and accomplishments.

What role must senior faculty and department chairs play in helping to effect the longer term changes necessary at the GSD? What are additional short-term actions all GSD staff and associates should take?

I have learned over the past few months that we are all products of our teaching. In turn, I am seeing how important it is for the leaders of the school to not only reflect on and be vigilant of themselves—their personal values and responsibilities in relation to their teaching practices—but also on the cultural legacies and structures that are inherent to our work. We need to challenge what we have inherited and what we have done to perpetuate power structures that minimize other perspectives. As we shape curricula and educations and experiences for a rising generation of architects—the designers who will determine our future—we risk further entrenching the very same problems.

It is a long-term project to instill an inclusive and humane culture for future generations, and especially for our junior faculty and our students. As a male architect in a leadership role, I acknowledge the power structures from which I have benefited throughout my professional journey. Now it is my responsibility to scrutinize those structures rather than rest upon them.

In the more immediate term, we can each do more to elevate and amplify Black voices and perspectives, whether that means bringing more Black architects into the center of our pedagogy, hiring and supporting Black-owned firms and businesses, or, as my colleague Sean Canty has been doing brilliantly, promoting and celebrating Black talent via our personal platforms and social media. We need to be more intentional in the awards we present, the fellowships we bestow, and the review panels we convene. Since such distinctions can really advance individual accomplishment, we need to be cognizant of equity in their distribution. But we also need to ensure that our juries and critics are composed mindfully from the start—one step toward mitigating biases in the projects and people that we choose to celebrate.

Why is it particularly important for architecture to respond to demands for spatial justice?

Like all of the design disciplines, architecture possesses the power to shape our thoughts, our behavior, our aspirations, our visions, and our hope for the future. Architecture is also one of the more visible or tangible of the design arts; so much of human history is written and expressed through buildings and spaces, and likewise, so much inequality and injustice has been inscribed through our society’s buildings and shared architecture. This amplifies our responsibility to demonstrate and act on the values we consider important, as well as to combat or counteract prejudice. Before urban planners or designers or landscape architects can design or reform at the scale of the region or the city block or the neighborhood, architects need to reconsider what we do at the scale of the building or the unit. Even decisions like the placement of a door or a window have social implications, especially as we scale upward.

Do you believe it is necessary to rebuild the entire curriculum in the Architecture Department in order to align the GSD’s teaching with its goal to “[educate] leaders in design, research, and scholarship to make a resilient, just, and beautiful world”? What new courses must be implemented? What skills should students be assessed on? What knowledge and abilities should they take with them when they graduate?

It is essential that we reorient our teaching toward a more inclusive model—adding new courses, knowledge, and skills to prepare architects to help address social inequity and distribute the world’s resources more fairly. At the same time, we need to examine our current curriculum closely and identify areas that, intentionally or unintentionally, have either contributed to or benefited from structural racism, social injustice, and perpetuation of social ills. Traditional narratives from the canon need to be coupled with counter narratives in order to expose architects and designers to varying viewpoints, but also to demonstrate and remind us all that the spaces we create should serve and be accessed by a variety of people.

We can do more to teach about the histories, politics, and philosophies in which architecture as a discipline has been molded over the centuries, both so we can situate our designers in a mindful social and cultural context, and so they can carry that mindfulness into their own practices and discourses. A GSD graduate should leave the school with not only sharp, top-level design acumen, but also a holistic and nuanced perspective on social and cultural history, given how much responsibility designers hold in shaping the world.

How can the GSD improve its outreach to, and engagement with, the greater Boston area, and its support of Black communities nationally and worldwide, both alumni and not?

We should look at both our admit and yield rates for Black applicants, and continue to question if we are engaging Black communities with enough outreach and genuine communication. Simply exposing more communities to architecture and design is a tangible first step. We can start here in Cambridge with high school students and recent graduates. Project Link is a good example of one outreach avenue, but we can continue to expand upon this model and create more opportunities for Black teens and young adults to learn about the design fields.

The GSD’s African American Design Nexus was launched to expose young people, especially young Black people, to Black excellence in design, and in so doing, show these students that design and architecture are opportunities they can take. We can certainly do more both to recruit and support design talent and to foster dialogue across the country, especially at HBCUs, as well as throughout the Caribbean and Africa. Architecture has created an enormous vacuum in Black design talent in part because we have failed to make architecture a legible, accessible idea or opportunity to so many cultures and people.

Mark Lee is Chair of the Department of Architecture and Professor in Practice of Architecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design. He is a principal and founding partner of the Los Angeles-based architecture firm Johnston Marklee.