Mount Lebanon, NY has faded. When its last seven inhabitants moved away in 1947 it was already diminished, and now it is an exquisite shadow. For 160 years, 600 Shakers built a community in hundreds of buildings on 6,000 collectively owned acres. Just 10 original buildings remain, and the town has become one of the most endangered historic sites in the world. Last fall, Preston Scott Cohen challenged 12 GSD students in his “Post-Shaker” studio to propose architectural designs for Mount Lebanon as it enters another time of transformation. With the Shaker Museum’s purchase of a new building for its collections in Chatham, NY, and a successful implementation of an artist-in-residence program in Mount Lebanon, the village will take on new life. Cohen asked his students to envision this revitalization and to “speculate on the establishment of a new art colony” there.

The site presents great challenges primarily because to design for Mount Lebanon today, Cohen explains, is to “operate in a very complex middle ground” between an inaccessible past and an indeterminate future. It requires consideration of the strict preservation that is already under way and the inevitable need for adaptation of the site as it accommodates new functions. In this context, Cohen proposes that designers must address the austere formal language of Shaker design, not merely as a set of historical design strategies and elements but as an expression of the Shakers’ unorthodox cultural ideals, which are still deeply relevant as fragments of the village persist.

After their founding in England and subsequent emigration to the United States in 1774, the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing (as the Shakers referred to themselves) established communities in New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maine, New Hampshire, Ohio, Kentucky, Florida, and Indiana. These believers, like many other European religious groups—Puritans, Calvinists, Quakers, Baptists, Anglicans, Presbyterians, Methodists, Catholics, Pietists, Unitarians—settled and thrived in the American colonies. Each had its own idiosyncrasies, but the Shakers were perhaps the most unusual among these groups.

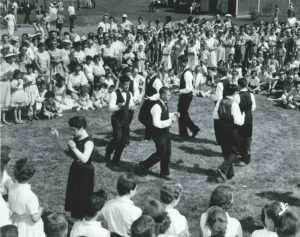

Aside from the rapturous dancing, twitching, and gesticulation in the services that distinguished their worship, the most consequential difference between the Shakers and other religious groups lay in their rejection of the typical male dominance over spiritual life. They believed that “Christ’s Second Appearing” manifested in their first leader, Mother Ann Lee, whom they saw as the personification of the feminine part of God’s duality. Accordingly, the duality and balance of the genders became central to Shaker beliefs, and it strongly shaped their way of life and the buildings that accommodated it. Cohen explains, “The Shakers believed in and practiced pacifism, gender and racial equality, and celibacy” and that the precise formal language of design they developed reflected these principles.

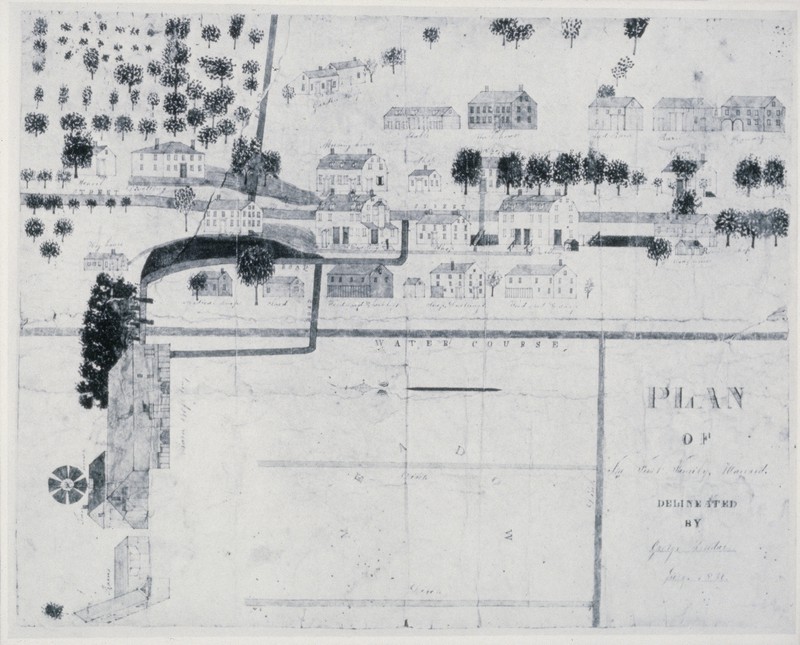

To ensure the integrity of their lifestyle and to avoid persecution, the Shakers almost completely removed themselves from the larger society around them. They formed autonomous communities of self-sufficient “holy families” that developed efficient agricultural techniques, productive craft workshops, and a highly refined version of American vernacular architecture. The village of Mount Lebanon was the first of these and acted as a model for other Shaker communities elsewhere. Founded by Lee’s successor, James Whittaker, after her death in 1784, it grew rapidly to include six holy families—Church, Second, South, Center, North, and East. The largest of these, Church Family, included 233 adult members by 1789. The egalitarian and communal nature of Shaker communities eliminated traditional, paternal family structures and other social hierarchies, but maintained strict separation of male and female roles.

Men and women shared leadership of the community, but assumed different responsibilities and produced different things—men built the furniture and women wove the cloth, for example. This played out in all aspects of family life and in the ordering and design of their buildings. They distinctly separated male and female work spaces and sleeping quarters but joined the family together for worship, meals, and other communal functions. Cohen points out that the “binary/non-binary treatment of gender roles” strongly affected more than just the arrangement of spaces in the Shaker village, however. It also controlled the fundamental character of Shaker design, which had “a very particular formal language” that played out at all scales, from the organization of buildings to the precise articulation of the smallest details.

So, when Cohen challenged students to design a new building for an art colony in Mount Lebanon, the central question he asked them to keep in mind was, “What would the Shakers have done?” Answering this question, they could begin to “speak the Shaker language in their own accent.” They would need to do this while navigating between the requirements of preservation and adaptive re-use, and with an understanding that Shaker design resides somewhere between an American rural vernacular and a precise functionalism that, Cohen proposes, is almost “proto-modern.”

The studio began with research about Shaker culture, its differentiation of genders and their labor, its connection to the outside world, its design language. The studio group also visited Mount Lebanon, where they studied the Shakers’ buildings and products. They examined particular sites between the existing buildings that were formerly occupied by North Family. Most of these are typical of Shaker architecture: simple rectangular forms with gabled roofs, white clapboard siding, symmetrically arranged windows, and gender-specific doorways, work spaces, and circulation. However, prominent among these buildings, the stabilized ruin of an immense stone dairy barn built in 1859 is unusual and inconsistent with typical Shaker design, complicating visitors’ conception of Shaker architecture. This added to the complexity of the students’ task of designing to fit into a Shaker context.

Throughout the studio, Cohen explains, it was necessary for students to “find a way to work on cultural connections.” They had to develop a clear understanding of the Shakers’ formal language as a manifestation of the community’s unorthodox values, while also finding “the motivations inherent to [their] own intuitions, ideas and plans,” which are naturally reflective of contemporary culture. Design work started with experiments in symmetry. In the studio brief, Cohen emphasized that the Shakers’ formal language involved complex symmetries.These symmetries, which had both practical and divine overtones, became the springboard for the students’ rich design investigations. Cohen challenged them to play with symmetry: to develop, for example, “unusual dual symmetry” at the scale of rooms; “alterable symmetries” using movable walls and furniture; complex volumetric symmetries in stairs and circulation systems; and “oddly symmetrical” arrangements of building masses using “typical features of Shaker traditional buildings (gables, dormers, typical windows and doors…).” The key in these exercises was to explore new accents of Shaker architecture that were “plausibly Shaker in sensibility.”

While much of the inspiration for these experiments in architectural symmetry derived from traditional Shaker design, Cohen emphasizes that it also developed out of his own long-standing interest in complex architectural symmetries, dating back at least as far as his 2001 book, Contested Symmetries and Other Predicaments in Architecture, which describes methods of creating complex designs using geometrical operations on familiar forms. The students’ final designs for Mount Lebanon in the “Post-Shaker” studio demonstrate how effectively the precise architectural language of Shaker architecture lends itself to the geometrical operations Cohen and his students explored. Each project seems simultaneously familiar and strange. Simple, gabled volumes shift and overlap; precise moldings wrap around doors and windows into the deep space of interpenetrating rooms; volumes twist with the terrain and struggle to maintain balance; rectangular doors and windows reflect across multiple oblique axes; gender-specific stairs and hallways wrap around each other only to join at unexpected moments.

While the Utopian Shaker experience of Mount Lebanon has long faded, its precise architectural language still speaks loudly today. The “Post-Shakers” in Preston Scott Cohen’s GSD studio found and voiced 12 new inflections of that powerful idiom.