Until the last decade, Native American, First Nations, and other Indigenous architecture has been a glaring gap in North American architectural discourse. The increased recognition of Indigenous peoples and their continued push for self-determination, however, puts a spotlight on land use on Indian reservations and in other areas with large Indigenous populations.

Daniel D’Oca, associate professor in practice of urban planning at the GSD, asked students to engage with Indigenous architectural issues in two sequential studio modules this term. The first—“This Land Is Your Land”—focused on Minneapolis, which was built on land stolen from the Dakota tribe. Minneapolis’s Native American Community Development Institute (NACDI) hopes to bolster the growth of the country’s only America Indian Cultural Corridor in a city home to one of America’s largest urban Native American populations. The second studio (which is still in progress)—“As of Right: First Nations Reclaim the City”—looks at British Columbia, where the Squamish Nation seeks to build diverse new projects on its undeveloped reserve land, including 11 acres of the former fishing village Senakw, which lies within Vancouver.

Historically, “urban” and “Indigenous” have been cast, psychically and physically, as opposing identities. Indian reservations in the United States—of which there are about 300 in 36 states, comprising over 50 million acres of land—were intentionally situated away from metropolitan areas and especially in areas not deemed desirable by white populations. This enforced isolation reinforced the long-held colonialist project, both conscious and unconscious, of removing these societies from those of the settler colonialists by separating them from roads, cities, towns, and, in some instances, natural resources. While the Indian Relocation Act of 1956 brought more than 100,000 Native Americans to urban areas, it did so with an assimilationist agenda. It sought to eliminate Native American identity through the intentional severing of family and community ties which the federal government saw as counterproductive to promoting American nationalism after World War II.

“Conservative terminationists [the term used to describe those who supported these assimilationist policies] saw traditional Indian communal social structures as too similar to the dreaded communist systems that they perceived the United States to be in conflict with during the Cold War,” Larry W. Burt writes in American Indian Quarterly. “Separate governmental and landholding status, federally-supplied services, and the continuation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs itself violated a politico-economic system based upon individual property rights and private enterprise that conservatives saw as the foundation of the American system.” Today, up to 72 percent of Native Americans live in urban areas, where they experience nearly twice the rate of poverty, unemployment, and under-education as the general population, with outsized homelessness rates as well.

In Canada, over half of the Indigenous population—First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples—live in cities. They, too, have historically been subject to a holocaust and the systematic annexation of their land—in large part, a result of the Indian Act passed by Canadian Parliament in 1876. The edict prohibited First Nations peoples from freely leaving their reservations, forming political organizations, speaking their native languages, and practicing their religion. Key to the federal government’s intentions to eradicate First Nations identities was the establishment of the residential school program, where abuse was also prevalent. A Truth and Reconciliation Commission formed in 2008 declared these schools a practice of cultural genocide.

The two countries’ relationships with Indigenous peoples have distinct differences though, particularly concerning land rights. Ninety-five percent of the land in British Columbia is “unceded,” meaning it has never been the subject of a treaty that gave it to settlers. “The City of Vancouver have been pretty progressive in some ways by acknowledging that the land is the property of the Musqueam, the Tsleil-Waututh, and the Squamish Nations. There is also a treaty process in British Columbia aimed at resolving First Nations’ claims,” D’Oca says. “Additionally, there are examples of First Nations reclaiming land through litigation and direct action, like in the case of Senakw, which is on highly developable, highly valued land in the middle of Vancouver. Because it’s an IR and Squamish administered, it’s not subject to zoning or the typical review process. Basically they can do whatever they want with it, which is why my studio is called ‘As of Right.’ While there remains a ways to go regarding these lands, this is a precedent-setting project and exciting that a First Nation was able to reclaim land in a major city. It may be a preview of what’s to come in the States.”

Considering this violent and exclusionary history, concerns about non-Indigenous architects working on Indigenous-related projects are legitimate. But these may be overcome through understanding and cooperation. The former begins with acknowledgements of recognition—of cultural identities and land ownership. “‘Native American’ is a huge umbrella term that in some ways has very little meaning,” D’Oca acknowledges. “The differences between tribes in the States and between the Nations in Canada are just as important as their similarities.”

In terms of cooperation and collaboration, the most productive genesis of a project is an invitation from a community. “I believe strongly in the philosophy ‘nothing about us without us,’” D’Oca says. “In my classes, we always strive to do as much engagement as we can with people who hold diverse opinions. For both studios, we set up a series of discussions with people who work in the neighborhood, leaders who are in touch with the desires and needs of the people in the community, and our client.” For the Minneapolis module, this included Louise Matson, executive director of the Minneapolis-based Division of Indian Work; Kelly Drummer, President of MIGIZI Communications, a local Native multimedia arts and youth mentorship organization; and Becky Wolf, a community embedded librarian at Franklin Library, located on Franklin Avenue which serves as the principal artery of the American Indian Cultural Corridor. “I don’t let students pick a project until we’ve heard a lot of different voices,” D’Oca says. “The idea is for students to listen, hear what the problems are and what people are working towards, and figure out what they can do to help.”

“These courses teach students how to engage in respectful dialogue,” says Heidi K. Brandow, a founding member of the Harvard Indigenous Design Collective (HIDC) and one of D’Oca’s teaching assistants. “The students are learning how to develop these kind of relationships, to listen, to work in tandem with these communities, and also to learn and understand Native communities’ contributions to the land from design, architectural, and planning perspectives. These conversations could potentially lead to long-term solutions.”

Also key to avoiding a practice of architecture-by-imposition that continues the violence and paternalism of settler colonialism is the studios’ engagement with goals brought by the stakeholders themselves. Unlike the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which long instituted plans that did not address the culture and needs of those who occupied those spaces, D’Oca’s students work from ideas suggested by locals. “For the Minneapolis module, NACDI had composed a document that expressed the priorities of the Native peoples from the neighborhood,” D’Oca says. “We knew they wanted an Indigenous farm, a center for Indigenous cosmology, job training, better transportation, and affordable housing. As a result, students were able to say, for example, ‘I know something about affordable housing, and while I’m not going to be the one to put the shovel in the ground, I can help move the needle.’”

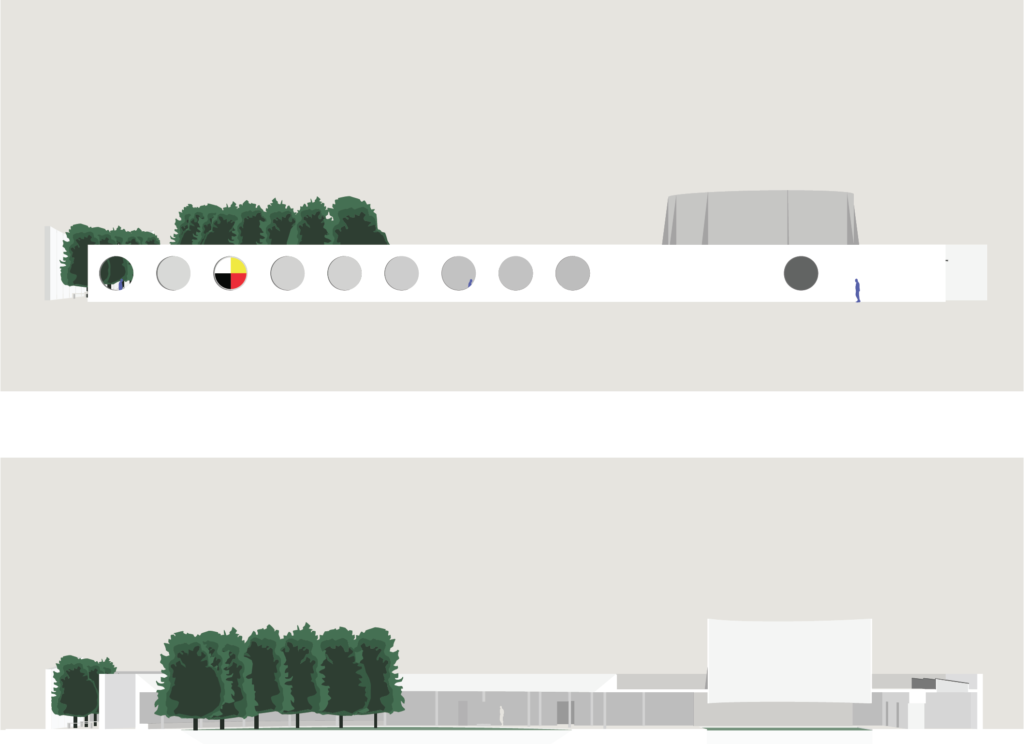

Kyle Winston (MArch I ’22) drafted a solution to the separation of urban life and ceremony. He cites a decades-long ban in Minneapolis that pushed Indigenous peoples to the countryside to perform their sacred rituals as a principal reason for NACDI’s request to bring ceremony into the cultural corridor. Winston’s project calls for the creation of “new grounds circularly inscribed within a rectangular site on Franklin Avenue” which include a mix of gathering and sacred spaces. An initial opening in the southeast corner invites anyone, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, to enter, while paths lead toward the site’s center where, he details, “[In] a cloistered garden, three of the four sacred medicines are grown: tobacco, sweetgrass, and sage.” In this space, “an exaggerated soffit directs one’s attention down to the plants, while up above, the sky is pushed away [and becomes] an object of contemplation.” “Red cedar trees (the fourth sacred medicine) frame the ceremonial activity, buffering the city’s hum beyond,” Winston continues, furthering the blend of publicness and privateness in an architecture that resists turning ceremony into a tourist attraction while also educating the uninitiated.

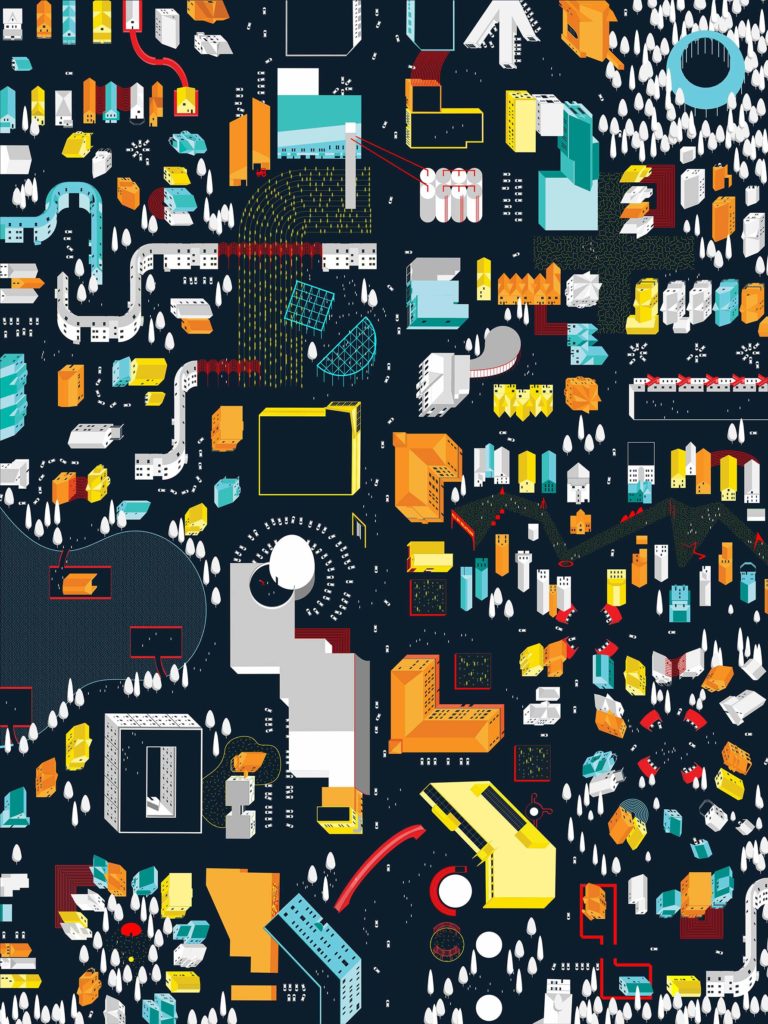

Rachel Coulomb (MArch I ’22) drafted a more speculative proposal by interrogating the colonizer’s violence against Indigenous peoples using property lines. “The Dawes Act of 1887 authorized the federal government to break up tribal lands by partitioning them into individual plots. Only those Indigenous Americans who accepted the individual allotments were allowed to become US citizens,” she notes. She proposes turning the land into a community trust instead, “where future programming is an agreement among those that live there, and power is placed back with the people through an environmental and social stewardship model.” The result, Coulomb argues, would be a “counter-cartography” that turns Minneapolis into “an expression of generational Indigenous values” and the map into “a depiction of stories” rather than an enemy.

Beyond the respect for the stakeholders in the community this approach entails, it also promotes a tempering, or even dissolution, of ego for architects and designers—an ethos that could be adopted in all interactions with clients, especially with those from cultures unfamiliar to one’s own. A new mode of design that speaks to architectural concerns broadly, with which non-Indigenous designers can provide assistance, while upholding specific cultural traditions may emerge as a result. Such creative collaboration, grounded in dialogue—and, arguably more importantly, listening—can synthesize diverse perspectives and lead to mutual education and growth for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups. “Pooling our resources at the GSD to create solutions is mutually beneficial,” says Brandow. “The Native communities benefit from hearing about these proposals, and I hope that the students will walk away with a deeper understanding of Indigenous people and will want to continue working with them.”