Black Harlem, storied and resilient, has been chronicled from many perspectives. Missing until now has been a thoughtful look at what is right before any visitor’s eye: its rich built history. A new project from the GSD’s African American Design Nexus, the Harlem StoryMap, considers the neighborhood’s many designed spaces created by Black architects and urbanists. The work of these professionals began before Harlem’s famous Renaissance in the 1920s and continues today. The StoryMap documents and celebrates this body of work, connecting each design with more familiar narratives about what American writer and civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson called the mecca of “colored America.”

The StoryMap is not a single map, but rather an interactive digital catalog of images, archival material, maps, news clippings, quotations, and audio footage. Users are able to study not only Black designs but also the communities and events that constitute their milieu. “The StoryMap is meant to peel back a layer of Harlem and engage with the stories behind the trailblazing designers that contributed to this place,” explains Thandi Nyambose (MUP ’21), who created the Harlem StoryMap.

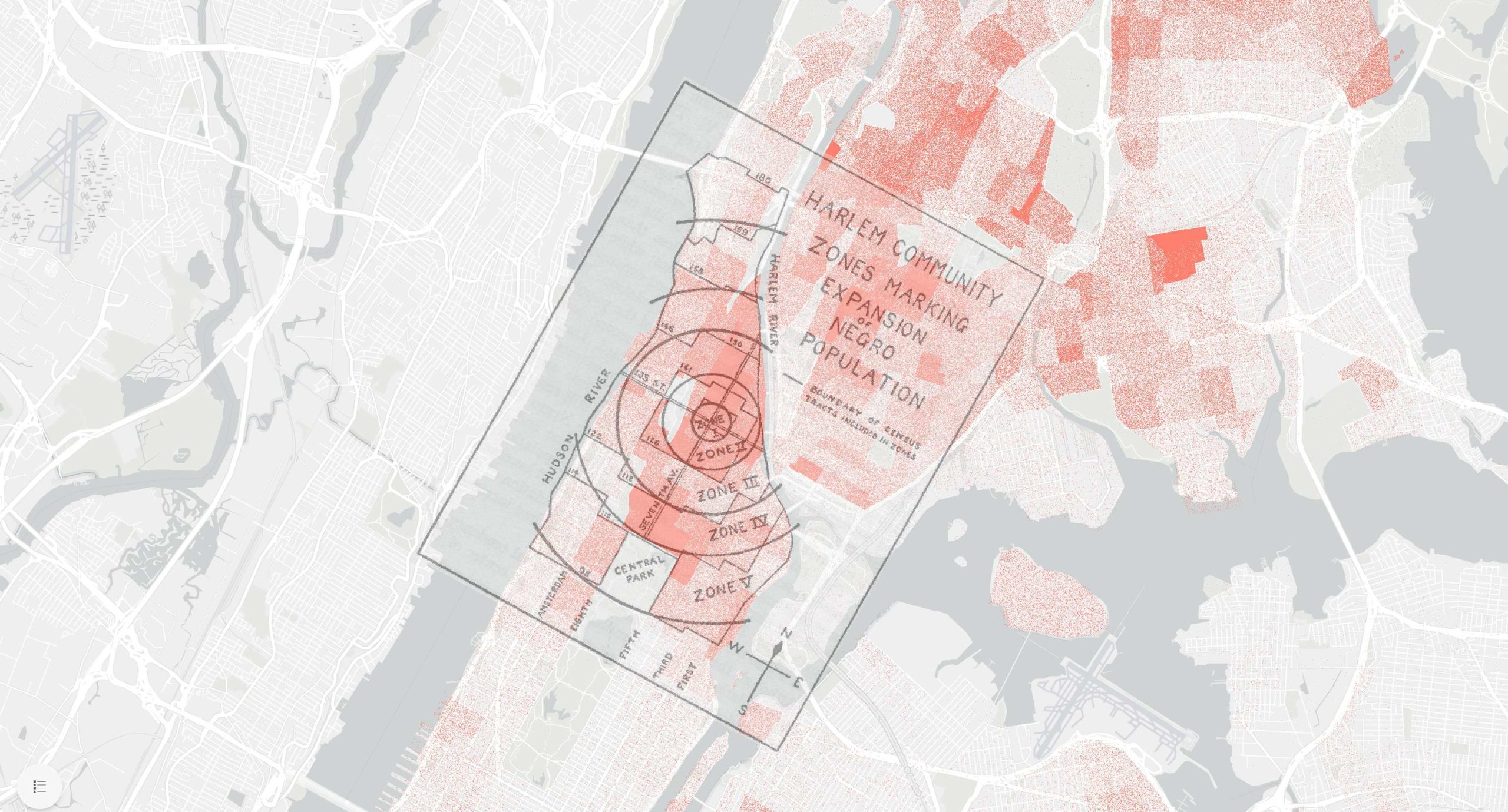

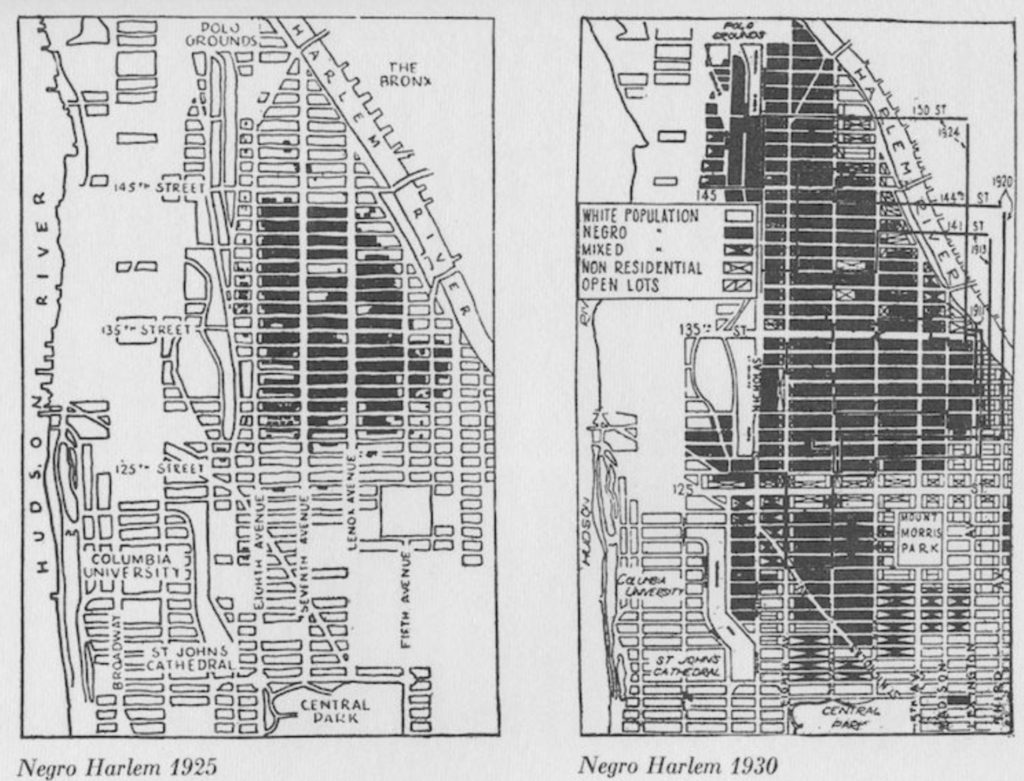

The web page opens with census and zoning maps depicting Harlem’s Black population boom between 1910 and 1930, before moving on to the first designs: two neo-Gothic churches by largely unknown Black architects. The first is St. Philip’s Church, the oldest Black Episcopal parish in the city, designed by Vertner Tandy in 1911; the second is George Foster’s 1923 Zion AME Church. “Using this style, they’re almost subverting traditional understandings of architecture and proving that in 1911, a Black architect is more than capable of designing a building like this, “Nyambose says. It is the first of the map’s many lessons.

Of course, well-known projects and facts are also represented: Black Astor Row, which became a magnet for African Americans migrating to Harlem in the 1920s and is being restored by Black architect Roberta Washington; the Adam Clayton Powell Building, designed by Ifill Johnson Hanchard at Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s behest; and the Studio Museum in Harlem, both the original—designed by J. Max Bond, Jr., one of New York’s most prominent Black architects—and the ongoing project for the new building, which is in the hands of the celebrated Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye.

But the map is also full of surprises. There are the first large-scale housing projects in New York City built by an African American (Tandy) expressly for African Americans in 1948, and the Heritage Health and Housing Headquarters (2002) by the architecture firm Caples Jefferson. Founded in 1987 by Sara Caples and Everardo Jefferson, a Black Panamanian, the firm planned the building to house a nonprofit that provides social services to the community. There is also Harlem’s first green building, 1400 Fifth Avenue, designed by Roberta Washington in 2004.

Because African American architects represent only about 2 percent of all licensed architects in the United States, Nyambose did not expect to find so many examples of Black-designed places in Harlem, especially so far back in history. “Every time I discover the history of a Black person who’s created something, who’s left a mark on culture, it’s energizing. The value of these stories being told cannot be underestimated—and told beyond the confines of the industry that they’re related to,” says Nyambose.

Familiar or not, the designs recorded in the StoryMap are all considered alongside the social, economic, and demographic shifts taking place when they were created. As the page scrolls through history, an image of each project is accompanied by eloquent, contextualizing text that adds to our appreciation of the vitality but also the vulnerability of the place and its Black residents. Nyambose reflected on the constructions “not just as static buildings or sites, but also as points of intervention that existed in Harlem, a very complex web of social, cultural, economic ecosystems.”

Some of the designers brought these forces to bear on the designs themselves. John Louis Wilson’s 1937 Harlem River Houses were an experiment in public housing and a way to create quality housing options for Harlem’s low-income residents at a moment when there weren’t any. More recently, this purpose-driven approach has been responding to the threats of gentrification, the disempowerment of Black Harlemites, and the repositioning of Harlem away from its rich, Black cultural history. The StoryMap points out that while Harlem has seen an explosion in commercial development, there has been a steady decline in quality of life for many—poor schools, lack of jobs, decaying cultural capital. Four projects in particular are presented as working to counter these trends: The Heritage Health and Housing Headquarters, 1400 Fifth Avenue, the 2007 Kalahari Condominium Complex by Jack Travis, and David Adjaye’s 2015 Sugar Hill Development.

The StoryMap itself serves to push back against the erasure of Black Harlem and the living legacy of Black-designed Harlem. Nyambose explains: “There definitely is a dimension to this work that starts to engage with the conflict surrounding this rebranding, which is ultimately a pretext for the duration of the old, Black Harlem.”

Nyambose graduates this spring, but this digital archive will be preserved. Ideally, it will be expanded to include work from Black designers imagining the city’s next landscapes—not only in service of the African American Design Nexus’s mission to highlight African American designers and redress decades of their obfuscation, but also for Harlemites themselves. Nyambose reflects: “It’s my hope that although the neighborhood is transforming, demographics are shifting, and buildings have been erased, that Harlem residents feel pride in their neighborhood and its ability to foster creativity and elicit community and joy. I hope that Black Harlemites feel that they’re at the center of this narrative.”