Newspapers this week are swamped with headlines like, “What Went Wrong with the Texas Power Grid?” To anyone not intimately concerned with the details of American electricity distribution, this may seem like an odd way of referring to the current electricity crisis in Texas. Isn’t there one national grid? Actually there are three: the Eastern Interconnection, the Western Interconnection, and Texas. Energy scholars sometimes refer to this, tongue-in-cheek, as an infrastructural form of “Texas nationalism.” This week, the apocalyptic images coming out of Texas of icicles hanging from ceiling fans and long lines for grocery rations show the limits of Texas isolationism, but also the ways its energy sovereignty has been steadily undermined since the 1970s.

Lean, just-in-time production for critical infrastructure seems destined to fail catastrophically, and while excess capacity may not be ‘efficient,’ maybe it’s not such a bad thing to have the ability to keep millions of people alive in extreme winter weather events.

The reason that Texas is a lone grid state is both a fascinating political history and mind-numbingly bureaucratic. In the mid-20th century, electric utilities were the corporate giants of their era. Flush with capital and the perception of unlimited growth, these companies began to consolidate into multistate “holding companies”—or “octopuses,” as pro–public power politicians maligned them—and they learned to take advantage of their ability to shift costs and profits across state lines. Ultimately, the federal government under Franklin Delano Roosevelt responded with legislation to govern interstate electricity sales and, ideally, maintain electricity as a reliable and affordable public good.

Texas avoided much of the federal oversight that came with these new regulations by agreeing not to sell electricity across state lines. In place of federal regulation, in 1970, the state created the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) to manage the Texas grid. While ERCOT does maintain some connections out of state, Texas has largely remained a power island. As Rice University Professor Dan Cohan recently told CNN, “When it comes to electricity, what happens in Texas stays in Texas.”

By the end of the 20th century, however, Texas’s infrastructural borders could no longer keep financial investments from flowing across state lines. New federal legislation starting in the 1970s and continuing through the 1990s steadily eroded the “regulatory compact” that had normalized government oversight of private power monopolies and encouraged competition in both electricity generation and distribution. This new deregulated power landscape unsurprisingly drew the attention of investors from outside the state. Financial partners from elsewhere in the country and Europe began to reorganize the Texas grid according to market logic. New investments in wind, “natural” gas, and other energy resources began to generate and sell power for a just-in-time model–driven ERCOT that then allocated electricity to customers through a myriad of competing private retail providers. By the 2010s, electricity in Texas had earned the reputation (at least locally) for being “the most volatile commodity in the world.”

While energy deregulation was championed in Texas for everything from making renewable alternatives more competitive to reducing prices for consumers, it has had mixed results on both fronts. Though it has made both renewable energy and distribution sales more profitable for corporations, the physical infrastructure connecting producers to consumers in Texas has received decidedly less attention. Texas is actually one of the leaders in the country in energy generation, both renewable and otherwise, but lack of investments in cold weather protection has limited its ability to act as an energy safety net in extreme weather conditions. Again, the (infra)structural condition demonstrates how, in the deregulated grid, corporate cost-accounting eclipses public safety.

Thus, as profits from electricity sales move freely out of the state, the physical risk of grid failure has remained territorialized within Texas.

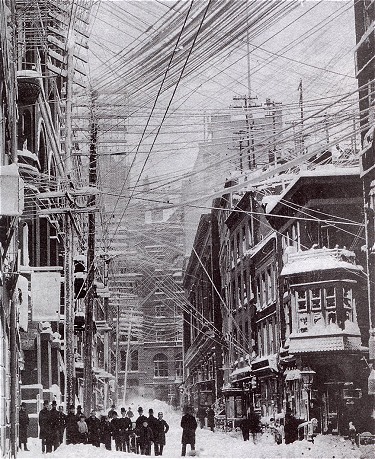

Last week, in the GSD Urban Planning and Design seminar “Experimental Infrastructures,” students debated the logic of redundancy in public utilities. On the one hand, it’s good to have legislation that prevents the massive tangles of wires that competing power companies enthusiastically built over each other in the early 20th century. On the other hand, lean, just-in-time production for critical infrastructure seems destined to fail catastrophically. Excess capacity may not be “efficient,” but maybe it’s not such a bad thing to have the ability to keep millions of people alive in extreme winter weather events.

Calling for reinforced or duplicated energy infrastructure may seem like an argument that is antithetical to climate action. But it actually reflects recent thinking on “energy justice” as a multifaceted problem that has to balance action on energy poverty with historic accountability for the production of high-energy lifestyles, or “luxury emissions.” What is fascinating and horrible about the current Texas blackout is that it shows that these two manifestations of energy injustice—energy poverty and energy luxury—can occur in the same location. The lean market reorganization of Texas’s historic energy abundance has created a landscape where, in a climate of increasingly volatile weather events, the line between luxury emissions and energy poverty has grown very thin.

Dr. Abby Spinak is an energy historian and lecturer at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. She is also area head of the GSD’s Master in Design Studies Risk and Resilience area group. Spinak’s current research ties the history of electrification in the rural United States to the evolution of twentieth-century American capitalism and alternative economic visions.

Dr. Sarah Stanford-McIntyre is an assistant professor in the Herbst Program for Engineering, Ethics & Society at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Trained primarily as a U.S. historian, her work focuses on how new technologies impact communities, shape social worlds, and change local environments.