Insects are indispensable creatures: vital pollinators, crucial recyclers of waste, the foundation for food webs around the globe, and a unique resource for medicinal purposes. As bioindicators, they are harbingers of ecosystem change. Yet they are often considered threats, plagues, or merely irrelevant, making them some of the most misunderstood animals on Earth.

Gena Wirth, design principal at SCAPE studio and visiting professor at the GSD’s Department of Landscape Architecture, is leading a studio that asks students to take a much closer look at these valuable species. Starting from the premise that “the health of insect populations is directly tied to the health of our landscapes,” “ENTO: Fostering Insect/Human Relationships through Design” prompts students to investigate human/insect dynamics and design for insects using a multidisciplinary and research-driven lens, and engaging with experts of ecology, entomology, horticulture, and landscape architecture.

We need to slow down a little bit and look more closely at what insects are telling us, at what their presence is telling us, at what their chemical composition is telling us. And, really view them as valuable cohabitants of the world that we live in, not as pests to smash or things to spray.

Estimates suggest that there are about 10 quintillion live insects on Earth, which is the equivalent of around 1.4 billion for every human. Of this staggering number, scientists have identified an estimated 5.5 million varieties, meaning insects represent close to 80 percent of the world’s living species. But research indicates their numbers are rapidly decreasing. “I think there’s a general consensus in the entomology community that we have a large-scale problem with insect decline,” Wirth says. In 1987, E.O. Wilson, also known as the father of ecology, gave an address at the National Zoological Park in Washington, DC, referring to invertebrates, and especially to insects, as “the little things that run the world.” Back then, Wilson also famously said: “If invertebrates were to disappear, I doubt that the human species could last more than a few months.”

“Urban environments and the way that we develop and build life on land is not necessarily helping or accelerating most insect life,” Wirth explains. Intensive farming, broadcast pesticide applications on crops, and climate change are altering populations. And many insects are susceptible to global warming: “They are very temperature-sensitive, and even the smallest changes can trigger large movements of species, the seeking out of new habitat types, and the adaptation to new environments,” Wirth says. Even seemingly innocuous human activity can affect insect development. Wirth uses the example of fireflies, which have evolved to lay their eggs on leaf litter. Something as common as a raked grass landscape means they can no longer reproduce or survive.

There is a lot about insects that is yet to be understood—including the exact size of their populations. And since many have not yet been discovered, it’s difficult to grasp the extent of their decline. “It’s almost like, we think there is a big problem, but we don’t know how big or what exactly is happening,” Wirth explains. “That’s the kind of space that design can operate well within. We’re a field that needs to propose action, adaptation, and change. We have to work in this environment of uncertainty, test new ideas, and put thoughts forward. So that’s really the aim of the studio: to test and foster new insect/human relationships using our design language and tools.”

As Wirth points out, there are many inspirational thinkers in the overlapping fields of insect conservation, gardening, and horticulture. “I would say that there is a trend towards ecological gardening, or a kind of backyard scale habitat improvement, which I think is having some momentum in the greater public discourse,” she says.

At the beginning of the semester, students traced relationships between certain insect taxa in rural, suburban, and urban sites of eastern Massachusetts. Field trips allowed them to take a closer look at insects and the impact many of these species could have on a single habitat. In one outing, the group participated in a guided tour with Harvard Forest’s Greta VanScoy, education coordinator & field technician, and David Orwig, senior ecologist and forest ecologist. They are researching the hemlock woolly adelgid, an invasive insect, native to Japan, that targets hemlock trees in North America and has killed millions of them in the eastern US. “We got to see first-person, from their perspective, the impact of one single species on an entire forest type that covers and blankets New England,” Wirth explains.

In the studio, students are conducting projects focused on particular species—investigating habitat requirements and needs during all the phases of the life cycle, as well as any changes that have been occurring. This advanced research is expected to develop into site-based design proposals. Although Wirth believes all insects should be preserved, she is careful not to impose such an opinion on her students. “Ultimately, the goal of the studio is to have [them] reflect on what is the existing [human] relationship with the species they chose, which might be one of admiration, or in the case of fireflies, for example, nostalgia but also neglect. Ignorance is also a relationship we have with many species that we don’t even know exist or know anything about.”

Students are not only defining the relationships that currently exist between insects and humans, but also determining the sorts of relationships they want to foster with their design process. Wirth notes, “Some of those are about expanding and supporting habitat needs or living in a more mutualistic or beneficial way with insects. And some are about being defensive with them. But that is all completely up to students and is very species- and project-specific.”

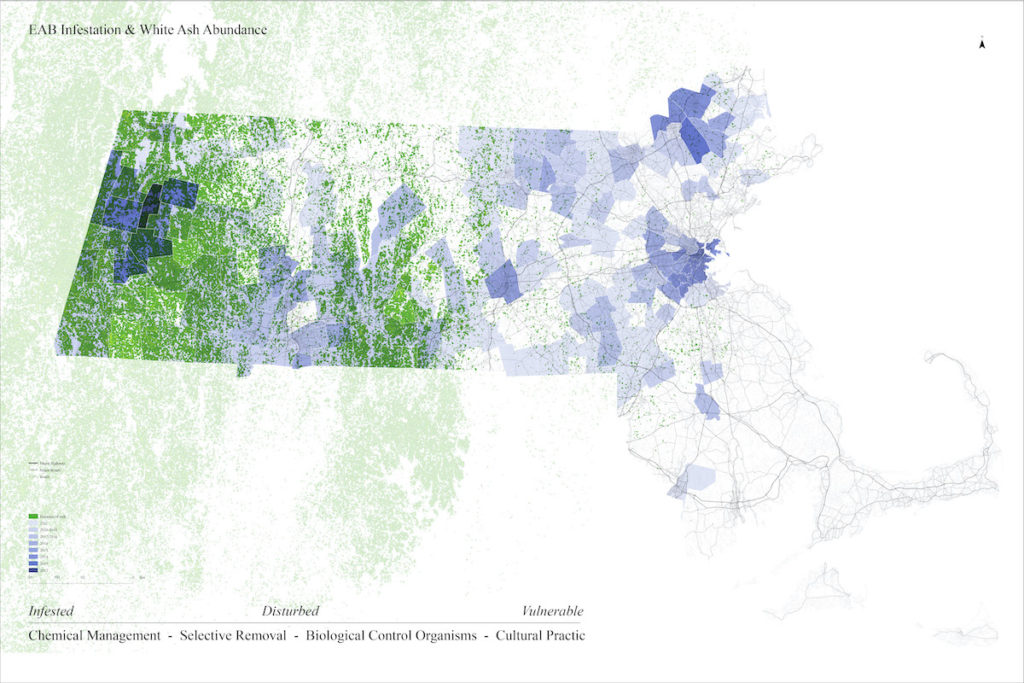

Sijia Zhong (MLA I AP ’22) is focusing on the emerald ash borer, a non-native wood-boring beetle that has been deemed one of the most significant threats to North American forests. As Zhong explains, the beetle—which is indigenous to northeastern Asia and was first identified in Michigan in 2002—was probably brought to the West through the global trade of wood products or packing materials. This invasive borer has already killed millions of trees and is a continuing threat to native ash trees.

One part of Zhong’s project is aimed at the economic impact this species poses to communities who find themselves having to remove dead ash trees by the thousands. Her design will address this issue by proposing “an on-site alternative to dispose and reuse the deadwood left by the emerald ash borer, and developing an urban deadwood habitat system to utilize the aftermath of infestation for nitrogen-fixing and local biodiversity restoration.”

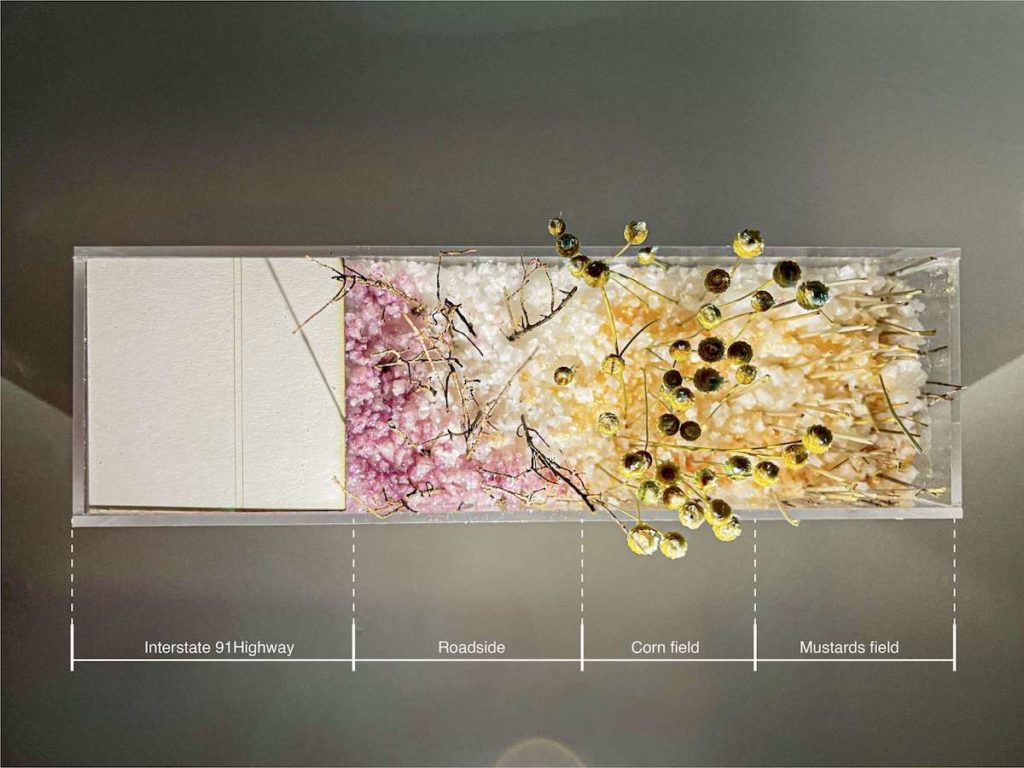

Liwei Shen (MLA I ’22) and Hyemin Gu (MLA I AP ’22) are researching the impact human activity has on monarch and cabbage white butterflies close to the I-91 highway, specifically due to the accumulation of chemicals such as zinc (emitted by cars) and neonicotinoids (heavily used in agriculture). Monarchs are vulnerable since they feed off milkweed, which grows on roadsides absorbing pollution, while the cabbage whites—an invasive species hailing from Europe—are much more resilient to harsh conditions. The duo is developing an “environmental justice” solution by designing butterfly corridors with vegetation species that can absorb pollutants and create balanced habitats.

Since Shen and Gu are looking at the highway, the roadside, and agricultural sites alongside the roadside, they are also interested in the way human needs, particularly local farmers’ needs, can intersect with those of the butterflies they’re studying. “We’re working with butterflies at the edges of farmlands, [so] we are also thinking about creating healthy environments for both human and non-human species,” they explain.

“No inch of the world is untouched by human impact,” Wirth says. Even landscapes that don’t appear to be affected by humans are reshaped by the innumerable human activities that accelerate climate change. “We are impacting these places. We are a part of these ecosystems. And we have to figure out how to be a better, more compatible part. I think that involves bringing in the greater suite of design tools. We need to slow down a little bit and look more closely at what insects are telling us, at what their presence is telling us, at what their chemical composition is telling us. And, really view them as valuable cohabitants of the world that we live in, not as pests to smash or things to spray.”