As early as the 1960s, movement artist Simone Forti began interrogating what dance is. In an attempt to engage with kinesthetic awareness and composition, she created Dance Constructions, a series of pieces that put the human body into precarious physical relationships with their environment. The dancers had to, for instance, ascend a rope-bound wooden incline (“Slant Board,” 1961) or hold their form on a rope loop suspended from the ceiling (“Accompaniment for La Monte’s ‘2 sounds,’” 1961).

Though she only received widespread renown and critical acclaim at the turn of the century, Forti influenced a generation of minimalist sculptors. In Thinking About the Body, a book about Forti’s work, she is quoted as saying, “I am interested in what we know about things through our bodies.” That sensibility is infused in “The House: A Machine, Queer and Simple,” a studio co-taught this past semester by Associate Professor of Architecture Andrew Holder and the dance and design duo Gerard & Kelly. The studio brief was to redesign Rudolph Schindler’s Kings Road House in West Hollywood, California.

This year, Brennan Gerard and Ryan Kelly are the inaugural Visiting Dance Innovators Program (VDIP) artists at Harvard Dance Center and Theater, Dance & Media. Theirs is a multidisciplinary practice, engaging with mediums of choreography, performance, installation, and video to delve into themes of gender, sexuality, queer subjectivity, memory, and the relationship between dance and visual art. One underlying goal of Gerard & Kelly’s work is to both subvert and propose alternative models to presenting identities, including those that challenge monogamous heterosexuality.

The Kings Road House has previously hosted Gerard & Kelly’s performance artwork Modern Living, which explored the themes of queer intimacy and domestic space within legacies of modernist architecture. It is often considered to be the first modern house designed specifically for the California climate, and it served as a prototype for what came to be known as the California architectural style. Designed in 1921 and executed in 1922 by Viennese expatriate Rudolph Schindler, the Schindler Chase house, as it is sometimes known, was conceived as an experiment in cohabitation—a formalization of the interest that his wife, Pauline Gibling, had in communal living. Originally, the house was intended to be shared with the Chace family—Clyde, a contractor who occasionally worked with Schindler, and his artist wife, Marian Da Camera. This was to be a live-work arrangement, so instead of bedrooms, each of the four were assigned a studio, joined via an L-shaped common area. The lines were blurred between indoor and outdoor, with the communal kitchen and “living rooms” (both interior and exterior patios) and “sleeping nests” on the roof, facilitating polyamorous, non-heteronormative lives a century ago.

Although the intended living arrangement dissolved even before the end of the decade, the house continued to be used by various configurations of its original inhabitants until Schindler’s death in 1953. The house also hosted a rotating cast of characters, including heterosexual couples and queer foursomes; genealogical families and families of choice; children and adults; and itinerant visitors, including at different points, Galka Scheyer, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage. It was the site of private domestic scenes as well as semi-public political gatherings.

Much like Schindler’s own design, the studio proposes a queer dwelling—in every sense of the term. Larger than a single-family home and smaller, and more personally entangled than an apartment building, the project is to house a mix of residents, visitors, families, and paramours, and thus begs for the reconsideration of the dwelling as a cultural and organizational form. Drawing inspiration from the works of Simone Forti and dancer/choreographer Trisha Brown, it is a first of its kind pedagogical experiment, combining architecture with movement-based practice.

We are interested in a kind of directness or an unmediated quality to our work that moves freely back and forth between the human body as a kind of a model and architecture as a design outcome.

Andrew Holder

According to Andrew Holder, the genesis of the studio was the national housing crisis as well as the changing definition of a family. The long-standing solution to the housing shortage has been density, either through repeating units in apartment blocks or in towers. However, Holder says, “That is not necessarily a solution that fits the problem of the day, for two reasons: one is that to repeat a type assumes that you know what a family is, and who lives in an apartment. And then also, to build at that density is just not what that many cities want to do, because that means such a radical change in the city fabric.” He continues, “And so, it occurred to my practice, the LADG, that what we need is a kind of a ‘stealth density’—something that’s bigger than a house, but smaller than an apartment building. Something that could be inserted into the city fabric with less violence, but also be more flexible in terms of the definition of the family unit. Part of this is to question how houses can sponsor new organizational patterns for how people live together.” This learning translated very directly into the studio, where students were asked how their experiments in unsettling normative plans and normative structural arrangements inspired ideas about how people share things.

Holder’s association with Gerard & Kelly goes back a few years, to when the pair was invited to the GSD as visiting media scholars in residence, to do a piece in the the 9 Ash Street house that featured in their Modern Living. The duo have a long history of reoccupying modern houses in a “wrong” or counterintuitive way: by confronting head-on the queer history of a house, they begin to reckon with its checkered inheritance. The collaboration for the studio evolved organically, initiated by conversations about what it means for architecture to be queer or nonnormative. They went beyond the traditional conception of the identity of the inhabitant, instead focusing on how design methodology may be distinct, with a different, disobedient notion of who the occupant is.

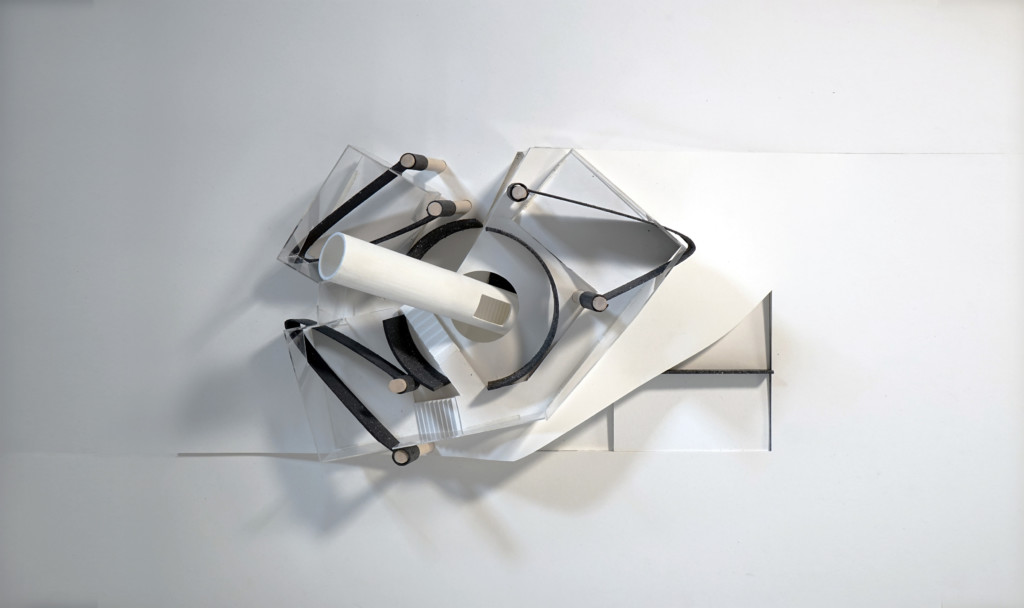

The studio sets up the dialectic between Le Corbusier and Eileen Grey by considering the analogy between architecture and machines—simultaneously conceiving of bodies using buildings and bodies modeling buildings. Buildings are considered as assemblies of simple machines, though they themselves have achieved a state of static repose. Holder says, “We thought a way to get to this question of how a nonnormative body would actually change design was to revisit the scene of Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions: that as she asks bodies to balance on an inclined plane—another way to think about that, is that she is asking the human body to find a kind of state of poise or repose in unsettled circumstances. And we decided to take that very directly into architecture.”

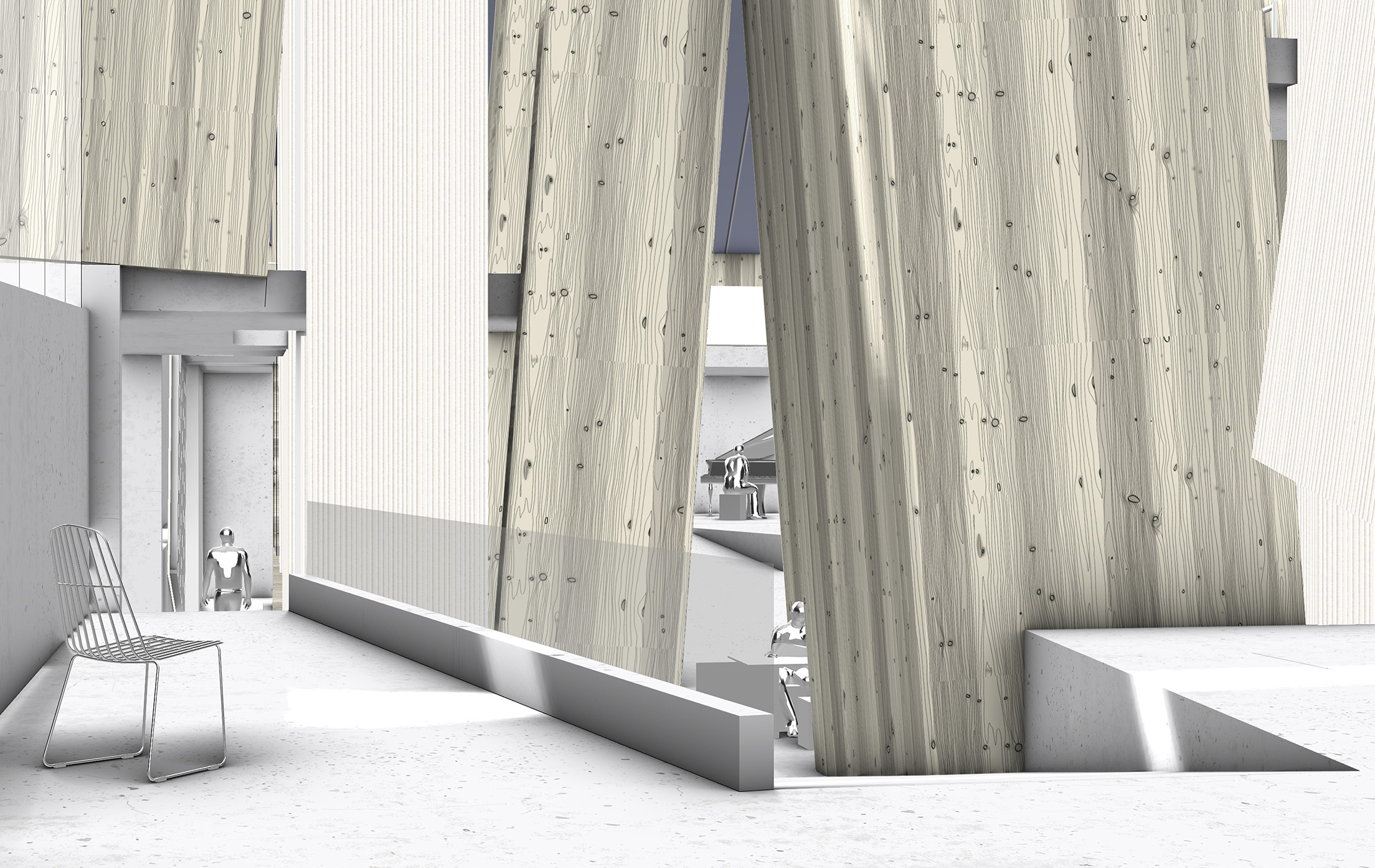

By virtue of maintaining a dynamic balance, within these unsettled circumstances and conditions, Forti’s Dance Constructions are structural models for how a house could be designed, and how it might work organizationally. Based on this notion, a program was developed to work with students in a dance studio, recreating some of these instances of stability and poise in an unsettled environment. Movement workshops, in engaging the body with simple machines, such as the inclined plane, pulley, and lever, aimed to fuse the body and the machine, to reposition the concept of queerness. The three workshops over the course of the semester prompted students to deploy their bodies to think through a building mass, a room, and a construction detail in turn. Students took what they learned from the experiments on their own bodies back into studio. Holder explains, “We are interested in a kind of directness or an unmediated quality to our work that moves freely back and forth between the human body as a kind of a model and architecture as a design outcome.”

The performative aspect carried through to the day of the final review: as the studio was introduced, the students reperformed some of their movement studies live. The movement studies reflected the massing and organizational models that the students had made for their projects. There was an easy and immediate legibility between the performance and the drawings and workshop photographs that were displayed, almost as if the bodies themselves were presented as architectural models.

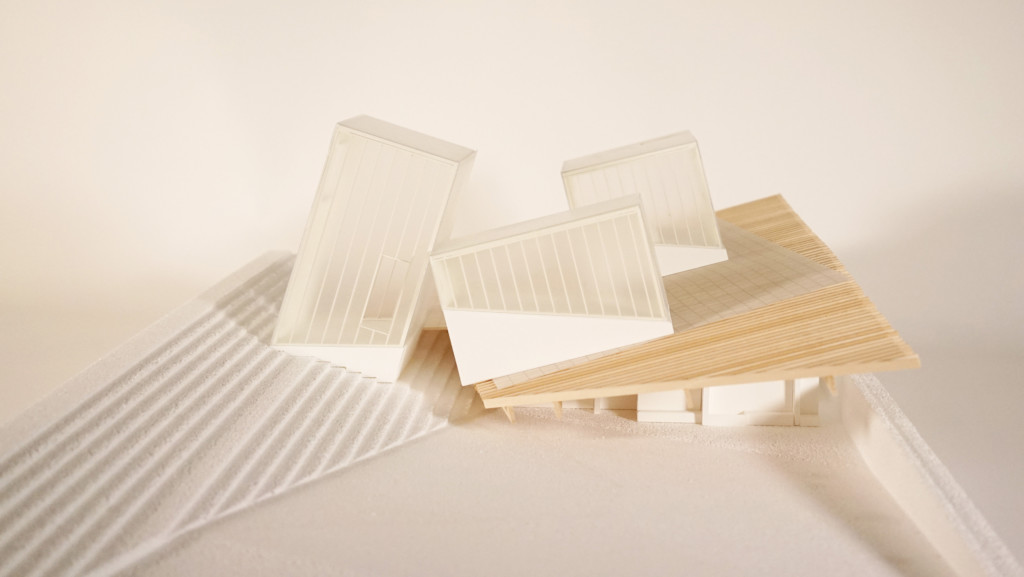

Holder was pleased at the students’ avid interest in the historical aspect of this project. They took the legacy of the Kings Road House seriously as they considered how unconventional groups might occupy a house. Each student interpreted the brief in unique ways. Elsa Maki (MArch I ’23) chose to focus closely on the experience of two children living in that queer arrangement. In her design, they were given free reign over the “attic” or the interior-exterior roof space, a form that paid homage to Schindler’s original sleeping arrangement at Kings Road House. It emerged from her discussions with Gerard & Kelly about a “realm for queer childhood that is somewhat distanced from the family, becoming both a little more public than the rest of the house in being more connected to the world at large than the domestic bubble, and a space to develop nonhierarchical and nonbiological siblinghood as its own kind of relation.”

Another way in which Maki tackled childhood and the issue of privacy was through surveillance. She distinguished between the kinds of space that produce a sense of proximity and cohabitation that is indirect, and ones that are more bluntly meant for gathering: categorizing them as a “glance” and a “gaze” respectively, creating an interplay of the two in her design.

“Make-Do with Rupture,” by Toby (Yung To) Chan (MArch I ’23), teases out the tensions that exist as a function of the house being a rental property. He brings up the dialectic between those who can “formally inhabit” and those who, because of their queer, sensitive, or oppressed identities, must “make do” with the space they are given. His cast of characters (two heterosexual couples, one gay couple, a queer nudist, and members of the American Communist Party) chance upon the landscape and set up camp; each set or identity situates a space on the dialectical spectrum. The heterosexual couples may be able to “formally inhabit” or even be landlords, while the Communists have to make do, or clandestinely inhabit space. Chan elaborates, “Queerness may on its face suffer from the rejection of the normative, yet the house provides a refuge and a more nuanced reading that the condition and desire to make do amongst formal inhabitation is part and parcel of queer identity, and what makes it thrive.”

Students came with varying degrees of comfort and exposure to dancing and movement workshops. For Chan, it was his first time doing a movement workshop. He says, “The experience was paradoxically highly intuitive and incredibly surprising. A lot of the workshops involved what Gerard & Kelly describe as ‘research’ on bodily reactions to shapes, geometries, and spaces created by architecture. Without any formal training in dance, I was gaining knowledge on dance and movement, but also uncovering hidden subliminal, even innate reactions to space with my own body in ways that offered satiating catharsis.”

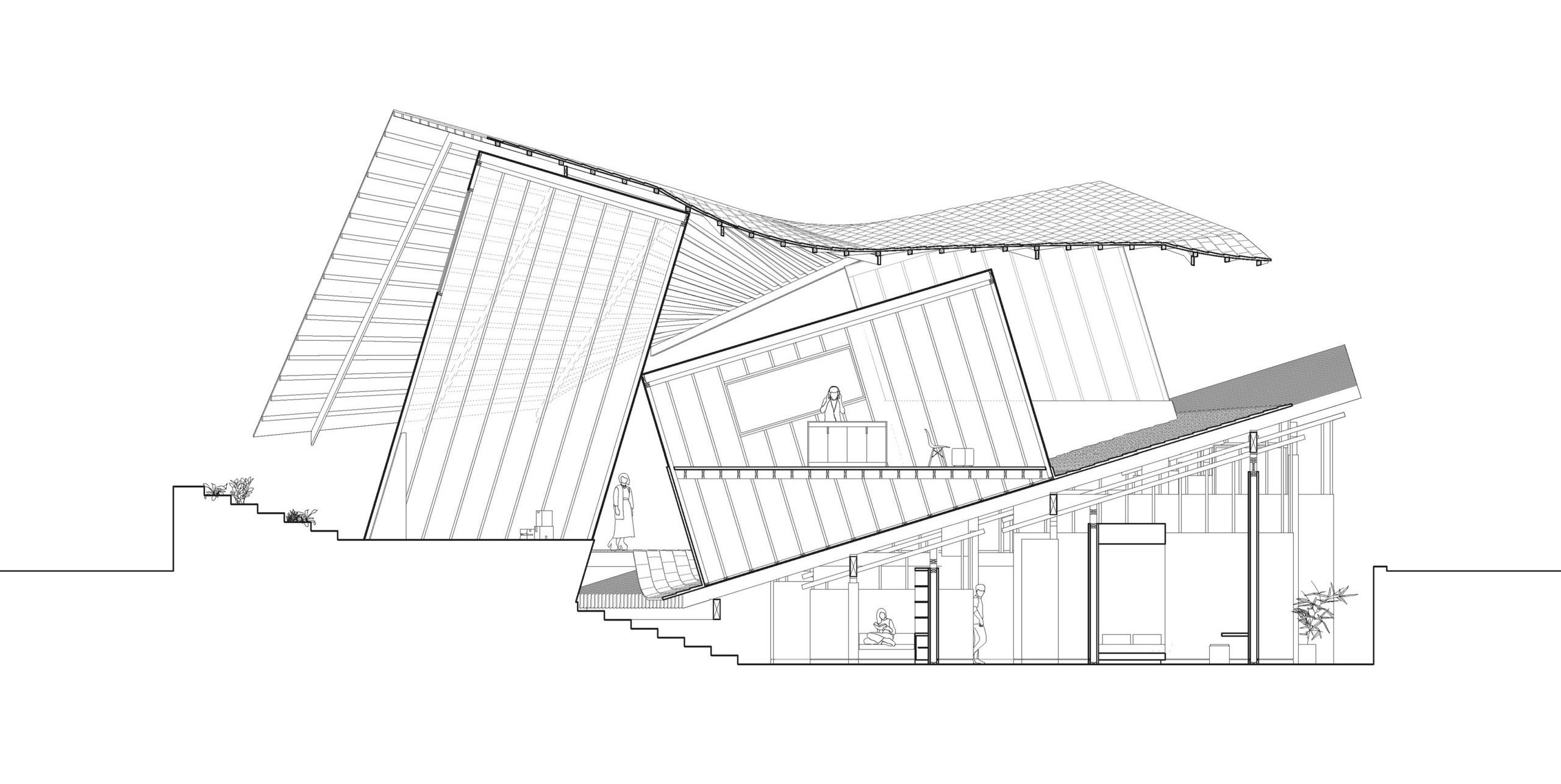

For Cindy Yiin (MArch II ’23), for whom it was the first time doing a movement workshop, the experience went beyond movement to become a study of embodiment: learning to think, feel, and express through physicality. Her cast of characters includes one widow and her spouse’s ghost, two-thirds of a throuple, and three parties of an open relationship, to imagine a house of asynchronous harmony. She says, “My project is based around a central thesis of finding stasis through friction. Physically and formally, the architecture consists of planes, boxes, and blankets finding stillness on inclined planes through oppositional and surface friction. Socially and conceptually, the ambiguity of interior and exterior, of scripted poche spaces and open floor plans, and of private and public accommodates a range of domesticities in this found family.”

Maki says, “For me, these characters had a slippery identity that applied both to a house originally constructed on this site in the ’20s for the purpose of ‘queer’ relationships and community-building in that time, as well as for what a queer family structure might mean now, approximately 100 years later, on a site that still facilitates artistic exchange and the formation of chosen families.” Through considering the many facets of queerness, this studio doesn’t only experiment with new design pedagogy, in integrating the spatial and experiential aspects of dance and movement with design, but it also revisits a housing typology that may very well be the solution of the future.