When she talks about her work, landscape architect Wannaporn Pui Phornprapha (MLA ’95) often begins with nature itself. “I have loved nature since I was young,” she explains, “rain, fog, animals, seasons, flowers in bloom . . . any natural phenomena with its ephemeral qualities.” That early fascination with natural systems set her on a path—first to architecture, then landscape architecture, and eventually to the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), where she found not just a profession but a collaborative approach to design.

Growing up, Phornprapha was unaware of landscape architecture as a distinct field. She knew that she loved both art and science and possessed an instinctive feel for space, so she enrolled in the bachelor of architecture program at Bangkok’s prestigious Chulalongkorn University. Initially, landscape remained peripheral, folded into a broader architectural education, until she interned in a small landscape practice. Watching her colleagues move fluently among design, art, and ecology, she recognized landscape architecture as the place where all her interests converged.

Following her bachelor’s graduation, Phornprapha went to work for Professor Decha Boonkham (MLA ’70), a GSD alumnus widely recognized as a pioneer of landscape architecture in Thailand. Under his mentorship, she saw how a relatively young field could take root amid older traditions of craft and ornament, and how landscape could operate simultaneously as infrastructure and cultural expression. Within a year, she applied and was accepted to the GSD’s MLA I program. “Since then,” she says, “my life has been bound up with landscape architecture.”

What Each Person Brings

Arriving in Cambridge in 1992, Phornprapha stepped into unfamiliar territory. The first semester, she recalls, was “very tough”—a collision of language, culture, and a design discourse that assumed an intellectual scaffolding unlike the one she had acquired in Thailand. Her MLA cohort was small, 18 students, and she was one of only two international first-years. English was a constant hurdle as she engaged with landscape theory, history, studio, ecology, and even rudimentary computer programming—a far cry from the hand-drawing world she knew.

At one point that first semester, overwhelmed, she went to Professor Elizabeth Meyer (who had yet to depart for the University of Virginia) and confessed that, with the language barrier, she struggled to understand—let alone discuss—the course material. Meyer’s response has stayed with her. Many students are gifted at analysis and critical argument, Meyer said, but Phornprapha brought something different: a powerful intuition about space and form. At the GSD, no one person has to be everything, Meyer insisted; the value is in the differences, in what each person contributes to the collective.

The insight that a community could function as a creative ecosystem became a central lesson of Phornprapha’s time in Gund Hall. Classmates helped her shape written arguments; she helped them untangle design problems. She shared courses with architects and planners, and a pivotal studio in Granada, Spain, demonstrated how a place’s relationship to gardens and courtyards could translate into contemporary design. She also became aware of oft-accepted boundaries—industrialized versus agricultural societies, modernism’s rejection of ornament versus Thailand’s exuberantly decorative temples—and of how arbitrary those lines could be.

Phornprapha emerged from the GSD with the conviction that transcending boundaries should never mean flattening differences. “The world is so big,” she says. “We don’t have to work with what we call ‘boundaries’—countries, cultures. Rather, I look to understand and value the differences.” This approach, first tested in studio conversations and late-night work sessions, would become an organizing principle of her life’s work.

Cultural Specificity in Practice

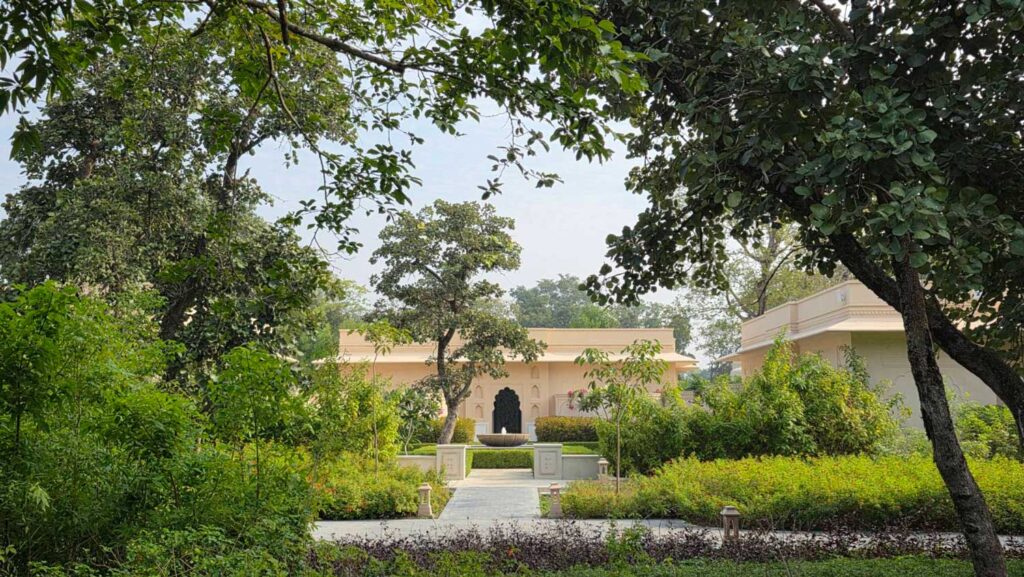

After graduating from the GSD in 1995, Phornprapha returned to Bangkok. Two years later, she established her own landscape and design studio, P Landscape (PLA). Her first major commission—in 2001, the Trident Gurgaon hotel southwest of New Delhi—immersed her in the layered histories of the Indian built environment, from Mughal precedents and Persian influences to complex codes around enclosure and procession. Studying ancient gardens and architectural details to unpack the project’s context, she cultivated a site-specific approach that would become a hallmark of her future designs. This attention to cultural nuance set the foundation for lasting partnerships; recently, PLA completed the Oberoi Rajgarh Palace—a major new commission with the same hotel operator and owner—demonstrating the consistency and trust that can accrue over decades of collaboration.

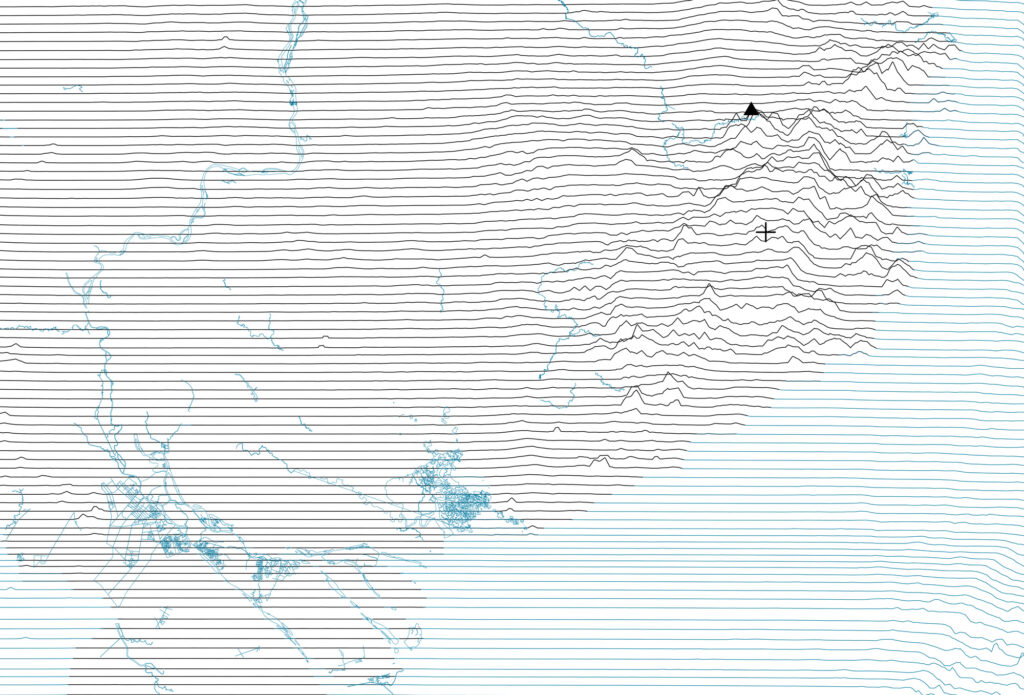

Over the years, PLA—now with offices in Bangkok, Chiang Mai, and Shanghai—has worked in more than 30 countries, primarily across Asia. “Everywhere we go,” Phornprapha says, “we try to find the essence of the culture and translate this into our design.” Sometimes that essence lies in plantings—species, patterns, histories—or emerges from the ways in which people occupy certain spaces. The work may be a luxury resort, such as the Rosewood Phuket (2017) in southern Thailand, or a regenerative landscape for a polluted site, such as Integral Eco-Industrial Campus (2020) for the Esquel Group in Guilin, China. These projects, alongside two others, are featured in the GSD’s spring 2026 exhibition Designers of Mountain and Water: Alternative Landscapes for a Changing Climates. Yet, regardless of project type, the goal remains the same: a landscape resonant with its setting that feels genuinely of its place.

While Phornprapha’s early career centered on hospitality—places where people travel to escape the commonplace—her more recent work often involves the everyday city, particularly Bangkok. Once called the “Venice of the East” for its network of canals, today the city is a dense, vertical metropolis of eleven million people, grappling with traffic, flooding, and scant park land. A lifelong Bangkokian, Phornprapha has become increasingly committed to urban landscape projects that dedicate fragments of privately owned green space to the public realm. She describes these as pieces of a “green jigsaw”—frequently embedded in hospitality, mixed-use, or residential developments—that together form a network of access to air, shade, and water. That patchwork depends on collaboration among public agencies, private developers, and communities—a pattern that echoes the way Phornprapha organizes her own practice.

Collaboration as a Way of Working

The principle of collaboration, emergent in that difficult first semester at the GSD, runs through every level of Phornprapha’s work. Within her office, teamwork is an ethic; she has built a collective of colleagues who together inhabit the full spectrum of what contemporary landscape architecture demands—design, ecology, social engagement, data. In recent years P Landscape has systematically gathered data—mapping tree counts, estimating carbon sequestration, monitoring temperature reductions—to understand how their projects affect urban conditions and to inform their future work.

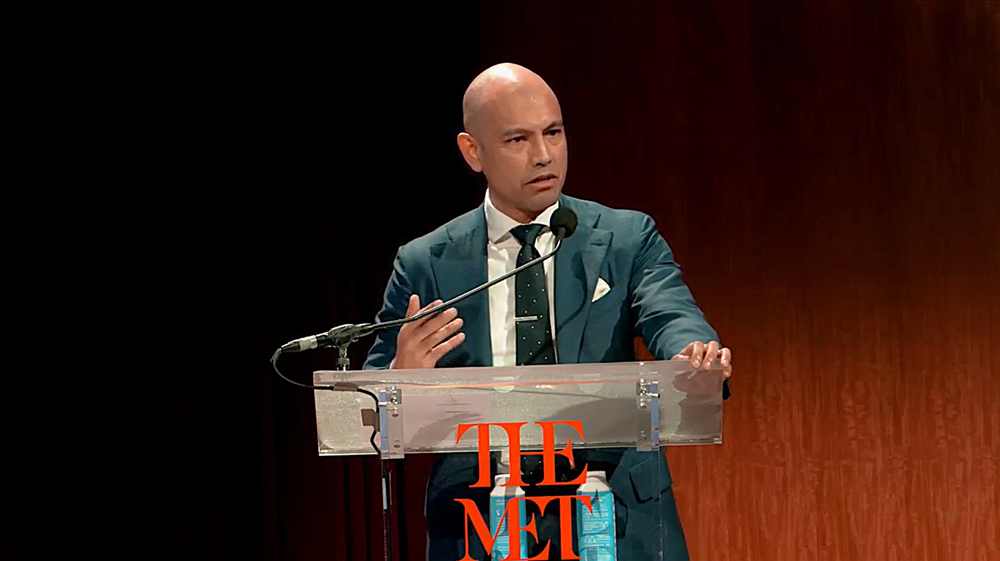

Phornprapha’s relationship with the GSD, too, has evolved into a long-term collaboration. Back in Thailand after her graduation, she became part of a tight-knit alumni network that welcomed visiting faculty—including George Hargreaves, Carl Steinitz, and others. When then-dean Mohsen Mostafavi visited, she hosted a gathering of Thai alumni at her office and then helped organize a GSD studio in Bangkok focused on low-income communities. More recently, through the Connect GSD Career program and as a member of the GSD Dean’s Council, she has continued her strong ties with the school. And in 2025, she was presented with the Harvard GSD Alumni Award, an honor bestowed “for her inspirational leadership and resolute dedication to fostering environments that celebrate cultural and natural diversity.”

That same commitment to shared learning and collaboration shapes how Phornprapha talks about her practice. She speaks about what the work makes possible, such as visitors delighting in a destination resort, or Bangkok dwellers reclaiming a canal-side park. Taken together, her landscapes embody the lessons she carried from the GSD: the value is in the differences, and the outcome grows from many kinds of knowledge interwoven with the particularities of place.