In September 2025, NASA introduced its newest class of astronaut candidates . From a field of more than 8,000 applicants, ten people were chosen—including Katherine Spies (MDE ’19).

Having served as a Marine Corps attack helicopter pilot and then as director of flight test engineering at Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation, Spies brings to NASA more than 2,000 flight hours and a record forged in high-pressure, technically exacting environments. Over the next two years, she and her cohort will undergo a training regimen equal parts scholastic and physical—ranging from learning foreign languages and orbital mechanics to navigating neutral buoyancy and survivalist scenarios—before being eligible for assignments that may take them to the International Space Station, the Moon, and eventually Mars.

This trajectory was fueled in part by Spies’s experience at the Graduate School of Design (GSD). In 2017, she joined one of the first cohorts of Harvard’s Master in Design Engineering program, a collaboration between the GSD and the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). As a student, she focused on the challenges of bringing hardware design and software development together in the creation of real-world products.

Recently, Krista Sykes of the GSD spoke with Spies about how the instinct for crossing boundaries she developed at Harvard has shaped the way she approaches complex problems at NASA.

Krista Sykes: Could you share a bit about your experience as an MDE student and how it connects to your work as an astronaut candidate?

I was incredibly lucky to be accepted to the MDE program shortly after it launched . One of the most remarkable things Harvard—and the GSD in particular—does is create opportunities for different areas of education and life to overlap. At that point in my career, I had realized it is not enough to be really good in a single discipline—you also have to connect that depth to other realms. The GSD gave me that opportunity.

I came in with an idea of what that interdisciplinary experience might look like, but once I arrived, my expectations were exceeded. I could find an area of interest, dive deep, and bring new frameworks directly into the work I do. That was one of the biggest takeaways: learning how to integrate skill sets from different domains to create new, even unexpected solutions—an approach that figures into my daily experience as an astronaut candidate.

Was there a specific topic you hoped to explore at the GSD?

I studied chemical engineering as an undergrad at the University of Southern California, so there was always this chemistry thread. And then, as an experimental test pilot in the Marine Corps, I was working through a product-development lens. With the MDE program, what I was trying to figure out how to begin bridging those pieces.

I spent time at SEAS exploring a few different areas within the chemistry space. But I realized the core of my work—and what I wanted to focus on—was hardware–software integration across the product-development pipeline.

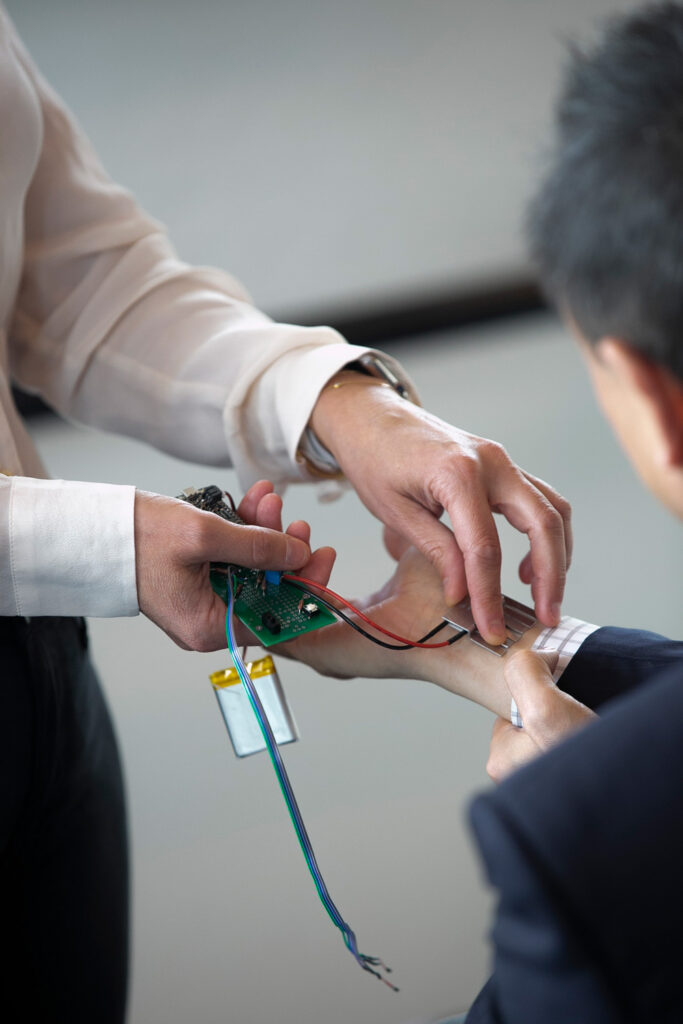

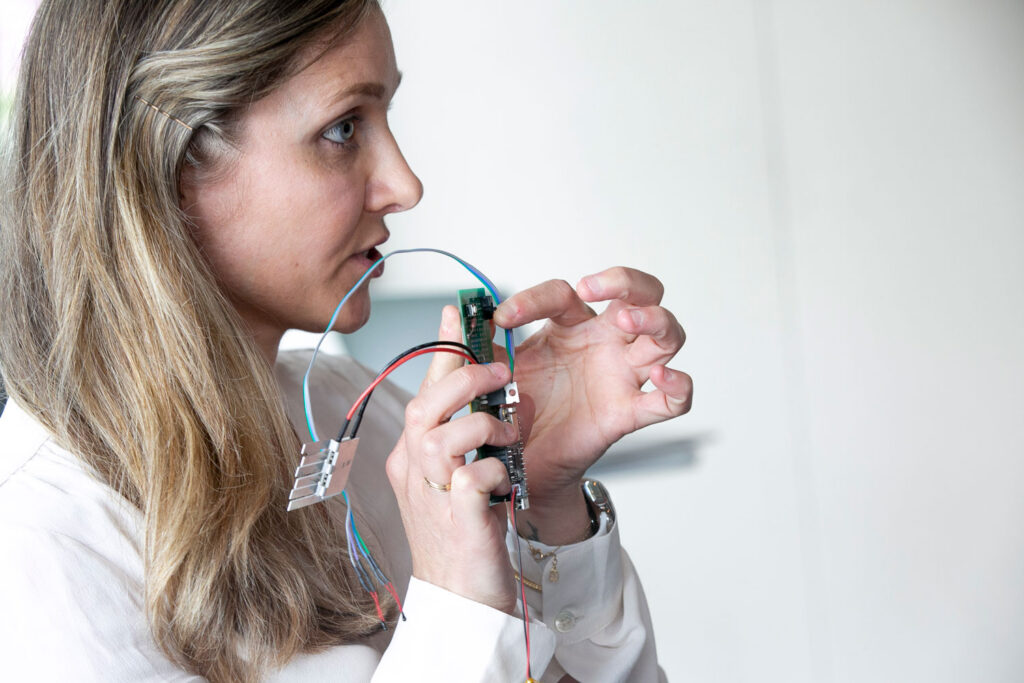

My final project was a small wearable device designed to break the cycle of doomscrolling and compulsive app use. Informed by research in psychology, the device created a specific effect—a sensation reminiscent of heat—as a signal to stop the activity.

It was really focused on how we might break out of addiction cycles, like gambling. What does it look like to design an intervention for actions we take each day—where we say, “I don’t want to do this; it’s not part of my ideal life,” and yet we can’t stop? You see versions of this today: people will “brick” their phone or switch to an analog phone. My wearable was another approach, framed around the concept of regaining individual autonomy in the face of challenging situations.

Did any GSD instructors have a lasting impact on you?

Yes—Martin Bechthold, one of the program leads, was incredible, and Andrew Witt as well. They were advisors for my final project.

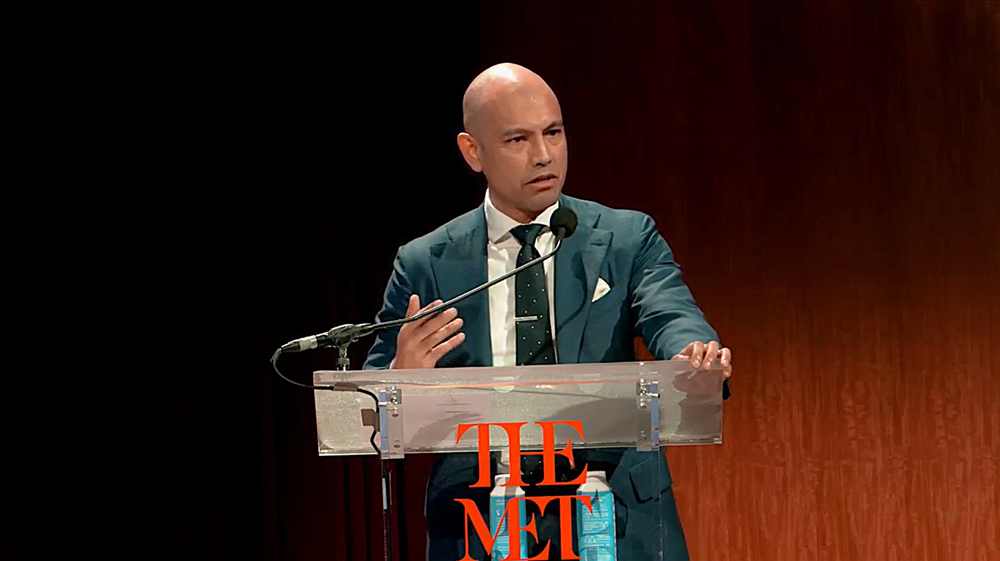

With every class I took at the GSD, the professors brought such deep expertise. One of my favorites was an elective with Jeffrey Schnapp . We dove into Italian design history, and you might think, how would this apply to what I’m doing? In reality, it gave me frameworks and historical reference points. These different histories shape the work I do and how I think through solving problems—here on Earth, and now beyond Earth.

Elsewhere you’ve talked about your love for applied sciences and engineering, coming together with others to identify problems and work toward solutions. How might this relate to your time at the GSD and the work you do now at NASA?

One thing I learned at the GSD—something I hadn’t learned before—is what it means to work collectively with so many people. The studio trays, the open work areas in Gund Hall, create a setup where people are always buzzing around, almost like a beehive, and you absorb that energy as you iterate. It’s an incredibly rich, rewarding experience; you want to keep working because you’re excited and curious where your project will go. Because the timelines are tight, “Yeah, let’s do that at 3 a.m.” becomes a totally normal thing to say—and other people are doing it, too.

I was inspired by how creative people were and their willingness to work hard to advance what they were passionate about. I hadn’t seen that degree of dedication prior to arriving at the GSD, and it raised the bar for what I expect of myself.

I see that same energy at NASA. People are deeply invested in the projects they’re working on, and it’s incredible to be surrounded by that kind of commitment. That was one of my favorite things about the Harvard GSD—and I find it here at NASA as well.