Designing for Disability Justice: On the need to take a variety of human bodies into account

Disability ought to be an exciting subject for architects: it’s about lived experience, problem solving, and designing a better built environment. While the topic engages with critical theory and aspirations for collective life, it’s often seen as a field that requires checking boxes and fulfilling requirements, or worse, a touchy subject strewn with outdated terms and outmoded habits of thought. The typical routines of design don’t always take the variety of human bodies into account. But I recently had the chance to talk to four practitioners who are changing minds and moving the field forward: Aimi Hamraie is associate professor of Medicine, Health, and Society and American Studies at Vanderbilt University; Sara Hendren (MDes ’13) is a professor at Olin College and the author of What Can a Body Do?; Sierra Bainbridge is senior principal and managing director at MASS Design Group; and Jeffrey Mansfield (MArch ’14) is a design director at MASS. In our interview, Hamraie says that engaging the design disciplines with the subject of disability requires epistemic activism. “When disability activists entered the profession of architecture, they showed that architects do not just design buildings, they also design curricula, licensing requirements, research, and fields of discourse that give meaning to their work. To shift the treatment of disability in architecture required intervening in all these ways, in addition to lobbying Congress to pass the Americans With Disabilities Act.” This sort of epistemic activism is occurring at the GSD. In the fall, Bainbridge taught “Seeking Abundance,” a studio which aimed to reframe the topic of disability as a source of diversity and potential. The studio relied on the expertise of Mansfield , who recently received an award from the Ford and Mellon foundations for his research into schools for the Deaf. While discussing how architects ought to think about disability, Mansfield, Bainbridge, Hamraie, and Hendren highlighted many examples that provide rich food for thought. Hendren points to De Hogeweyk, a “dementia village” in Weesp, the Netherlands. “It proceeded from the board of directors at a nursing home for memory care asking itself a simple but crucial question: Would the status quo for memory care be a kind of environment we’d want to live in, were we to acquire this condition? They created a list of values for promoting the kind of life they wanted for their residents, and their value of ‘favorable surroundings’ resulted in a cityscape structure for the redesigned site: a locked facility with streets and storefronts, a plaza, theater, grocery store—even bikes inside! And best of all: a restaurant that’s both publicly accessible to the town and internally, securely accessible to residents,” she says. “There’s an understanding among staff and customers that some of the residents will wander in from time to time, creating some unusual interactions. But the semi-porous structure is ingenious, lightening the barrier between public and private.” It sounds like a dream project for architects: reimagining public and private space while grappling with the nature of memory and human social interactions. Meanwhile, Hamraie mentions several notable figures: Jen White Johnson, who does graphic design work centered on #BlackDisabledLivesMatter and “Autistic Joy,” and Corbett O’Toole, a queer disabled elder and author of Fading Scars: My Queer Disability History. Hamraie says, “O’Toole has been a lifelong designer and pushed me in so many amazing directions when I first started to think about crip technoscience and DIY disability design. She recently retrofitted a school bus as an accessible space for living and traveling, and it is beautiful.” Hamraie cites precedents in theory as well: “The person whose work I always come back to is the feminist science scholar and activist Michelle Murphy, who writes about built spaces and vernacular designed objects in the context of eugenic, colonial, and imperialist projects.” Hamraie suggested two books by Murphy to start with: Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty and The Economization of Life. No doubt the greatest wealth of insight comes from the disability community itself. While a student at the GSD, Mansfield, who has been deaf since birth, initiated historical research into the design activism that occurred at schools for the Deaf in the United States. This has now become a multi-year research project exploring how Deaf schools became a node of design activism. His historical recap is illuminating: “Deaf spaces were typically designed by state agencies under the idea of benevolence. These schools were built with significant state investment, and they were built as symbols of societal virtue. They were not really designed for their deaf users—their sensorial needs are not accommodated by the spaces. It doesn’t help that they were built far from home communities.” But this segregation had an unintended side effect: “Clustering together deaf people at these schools allowed them to develop their own culture, their own awareness, their own value system. When it came time to assimilate back into society, it felt like a deprivation of this culture. Self-determination became a form of resistance.” Mansfield emphasizes how working within this framework can be a productive challenge for designers: “How can we identify unique forms of sensory knowledge, amplify them, and support these various experiences to allow communities to decide for themselves how they relate to the world?”I think the biggest barrier, of course, is the limited imagination that standards tend to create. Because it’s a checklist and a liability matter, the rhetorical framing of disability gets subsumed under that logic: a cloud over the excitement of a project, or a ‘don’t forget’ matter of inclusion.

on the barriers of standardization within the subject of disability in design

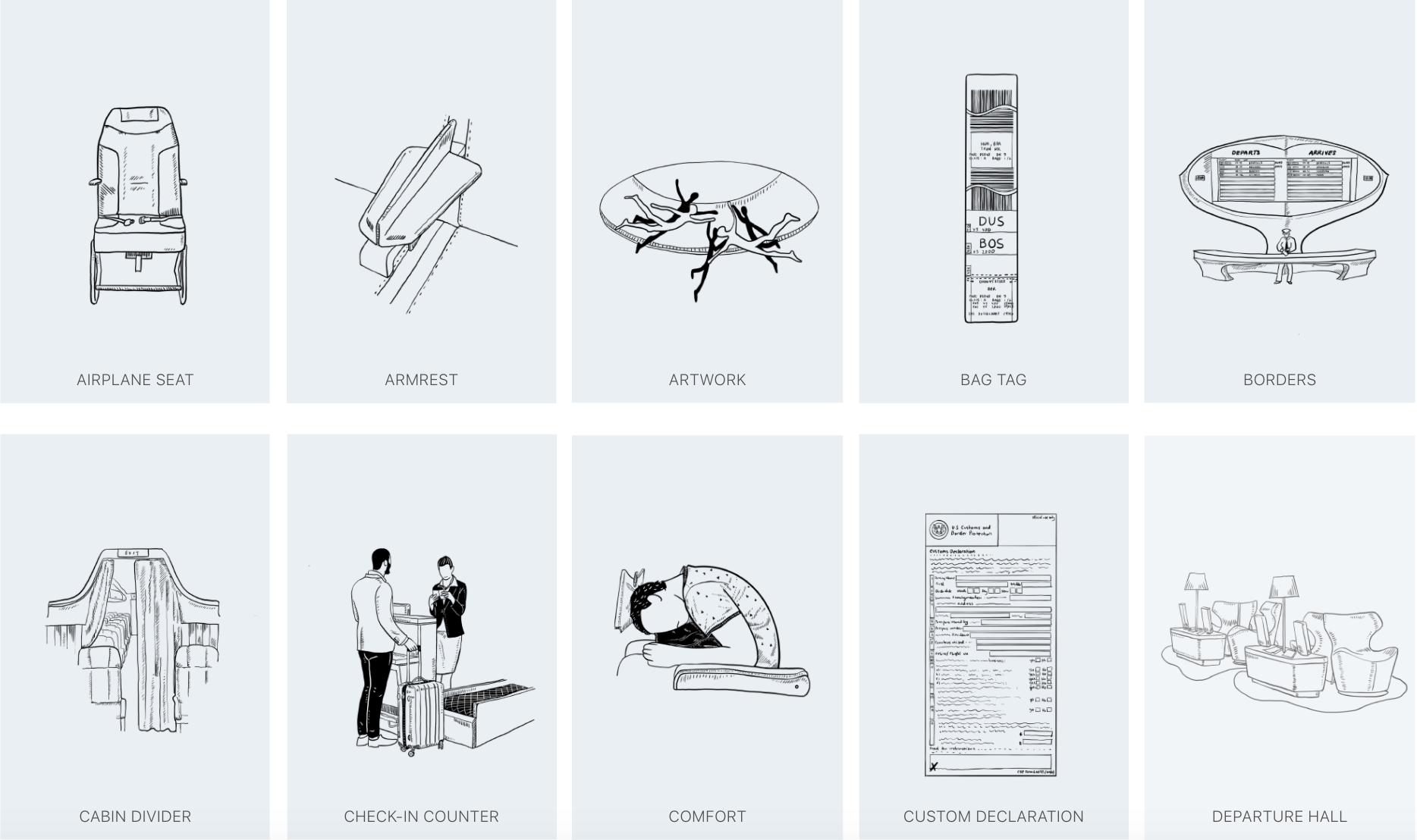

The Future of Air Travel: Toward a better in-flight experience

Anyone remember air travel? In early 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the globe and international flights were hurriedly cancelled, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Laboratory for Design Technologies (LDT) pivoted its three-year focus project, The Future of Air Travel, to respond to new industry conditions in a rapidly changing world. With the broad goal of better understanding how design technologies can improve the way we live, the project aims to reimagine air travel for the future, recapturing some of its early promise (and even glamour) by assessing and addressing various pressure points resulting from the pandemic as well as more long-term challenges. The two participating research labs—the Responsive Environments and Artifacts Lab (REAL), led by Allen Sayegh, associate professor in practice of architectural technology, and the Geometry Lab, led by Andrew Witt, associate professor in practice of architecture—“look at air travel from an experiential and a systemic perspective.” As part of their research, the labs consulted with representatives from Boeing, Clark Construction, Perkins & Will, gmp, and the Massachusetts Port Authority, all members of the GSD’s Industry Advisors Group.

Pre-COVID-19 meeting with researchers and Industry Advisors. Clockwise from far left: Bryan Kirchoff (Boeing), Hans-Joachim Paap (gmp), Jan Blasko (gmp), Isa He, Humbi Song, Stefano Andreani, Andrew Witt, and Zach Seibold. Allen Sayegh, Tobias Keyl (gmp), Kristina Loock (gmp), and Ben LeGRand (Boeing) were also in attendance.

On Flying acknowledges that it’s hard to quantify many of the designed elements—ranging from artifacts to spaces and systems—that affect our experience of air travel. So the toolkit methodically catalogs and identifies these various factors before speculating on alternative scenarios for design and passenger interaction. A year into the project, Phase 2 will more overtly examine the context of COVID-19, considering it alongside other catastrophic events, such as 9/11, in order to better understand and plan for their impact on the industry as a whole and on passenger behavior.

On Flying acknowledges that it’s hard to quantify many of the designed elements—ranging from artifacts to spaces and systems—that affect our experience of air travel. So the toolkit methodically catalogs and identifies these various factors before speculating on alternative scenarios for design and passenger interaction. A year into the project, Phase 2 will more overtly examine the context of COVID-19, considering it alongside other catastrophic events, such as 9/11, in order to better understand and plan for their impact on the industry as a whole and on passenger behavior.

Meanwhile, An Atlas of Urban Air Mobility, by Witt and Lecturer in Architecture Hyojin Kwon, is “a collection of the dimensional and spatial parameters that establish relationships between aerial transport and the city,” and it aims to establish a “kit of parts” for the aerial city of the future. Phase 1 considered the idea of new super-conglomerates of cities, dependent on inter-connectivity of air routes—specifically looking at the unique qualities of Florida as an air travel hub. The atlas investigates flightpath planning and noise pollution and other spatial constraints of air travel within urban environments. One possible solution it raises is the concept of “clustered networks,” where electrical aerial vehicles could be used in an interconnected pattern of local urban conurbations, reflecting a hierarchy of passenger flight, depending on scale and distance traveled.

Phase 2 will move into software and atlas development, expanding the atlas as well as their simulation and planning software. One intriguing aspect will be a critical history of past visions of future air travel: a chance to look back in order to look forward with fresh eyes. By studying our shared dream of air travel, the hope is to rediscover and reboot abandoned visions that may yet prove to inspire new innovations.

Meanwhile, An Atlas of Urban Air Mobility, by Witt and Lecturer in Architecture Hyojin Kwon, is “a collection of the dimensional and spatial parameters that establish relationships between aerial transport and the city,” and it aims to establish a “kit of parts” for the aerial city of the future. Phase 1 considered the idea of new super-conglomerates of cities, dependent on inter-connectivity of air routes—specifically looking at the unique qualities of Florida as an air travel hub. The atlas investigates flightpath planning and noise pollution and other spatial constraints of air travel within urban environments. One possible solution it raises is the concept of “clustered networks,” where electrical aerial vehicles could be used in an interconnected pattern of local urban conurbations, reflecting a hierarchy of passenger flight, depending on scale and distance traveled.

Phase 2 will move into software and atlas development, expanding the atlas as well as their simulation and planning software. One intriguing aspect will be a critical history of past visions of future air travel: a chance to look back in order to look forward with fresh eyes. By studying our shared dream of air travel, the hope is to rediscover and reboot abandoned visions that may yet prove to inspire new innovations.

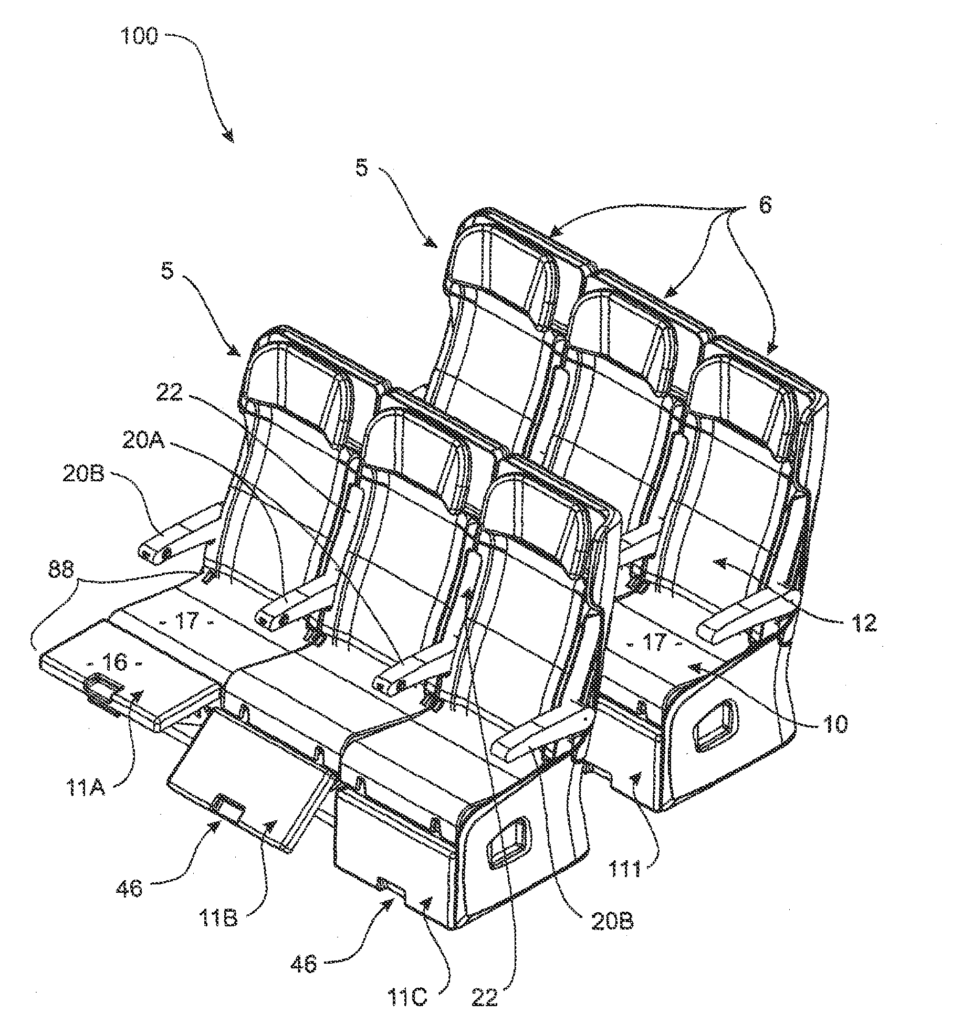

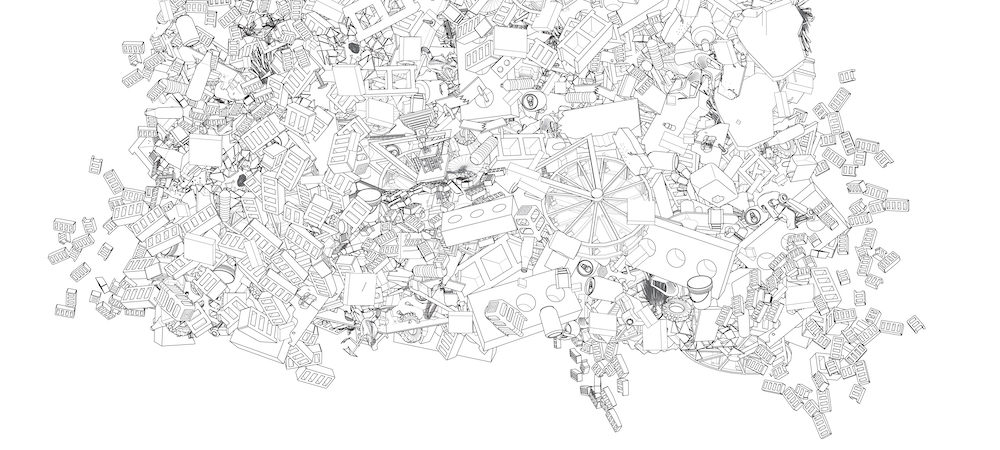

Armrest research from the Air Travel Design Guide: Patent for airplane seats showing ambiguity of armrest spatial “ownership” for middle seats

Spring 2021 All-School Welcome from Dean Sarah M. Whiting

On Tuesday, January 19, 2021 Dean Sarah M. Whiting joined the GSD community on Zoom to deliver a virtual welcome to start the spring term. A transcript of the Dean’s remarks is below. Good morning, afternoon, and evening everyone, and happy new year. I hope you all tried to have a restful holiday break. I just have to say, it’s so heartening to welcome everyone back to school for the spring semester. Many of us had been looking forward to the new year—I know I was—and I could not wait to put 2020 behind me. Twenty-twenty, though, is clearly not going away so easily. Today is January 19th, almost two weeks after the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. I’m still reeling from that day and I’m sure many of you are, too. By nature, I’m an optimistic person, but I admit I’m finding it very hard to find any silver linings right now. Yes, we have tomorrow’s inauguration to look forward to and yes, the vaccines are promising. (Speaking at a virtual conference of arts professionals over the weekend—and even dressing the part by wearing a black turtleneck—Dr. Anthony Fauci suggested that we might reach herd immunity this fall.) And yes, my surgery over break was successful, so I’m entering the new year in good health. All of these are positive, very positive, starts to the new year. But I can’t get the images of the rioters who broke into the Capitol out of my head. The vision of the confederate flag being carried within that space is particularly seared in my memory, confirming the work that this country has to do in reckoning with its structural racism, past and present. The U.S. Capitol, was designed by a succession of architects—the original competition, held in 1792, was won by Dr. William Thornton, who, according to the history on the Capitol’s website, was a “gifted amateur architect who had studied medicine but rarely practiced as a doctor.” Thornton’s original design was modified by Benjamin Henry Latrobe and Charles Bullfinch, among many others over time. Having partially burned in the war of 1812, it was rebuilt by European laborers working with American slaves. In short, this building embodies our country’s history as well as architectural history. In 1850, the building was expanded to create the House and Senate chambers—the two wings that swarmed with rioters early this month. Barton Gellman, one of my favorite columnists, described in The Atlantic what happened on January 6th as attempted “democracide.” Gellman concluded that “The republic survived a sustained attempt on its life because judges and civil servants and just enough politicians did what they had to do.” In other words, our system of checks and balances worked…just barely. Just barely because we discovered that facts, evidence, and history can be hijacked more quickly and more thoroughly than anyone could have ever imagined. We all need to be vigilant to prevent that kind of hijacking. It’s so important, so urgent, for us to pay close attention to what is happening politically, socially, economically, here in the U.S. and around the world, because yes, it does affect us. It is equally crucial for each one of us to be sure to base our research, our work, and our opinions on facts and on history that are backed up by evidence. I point you again to our event last September with Danielle Allen and Michael Murphy discussing “Our Common Purpose: Reinventing American Democracy for the 21st Century,” the report issued by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences that Allen co-authored. It’s available on the American Academy website. The report issues 31 recommendations, ranging from ranked voting to independent citizen-led redistricting in all 50 states, to subsidizing projects to reinvent the public functions that social media have displaced. While I would argue that every recommendation speaks to each of us as individuals, some, like redistricting and the ones challenging the space that social media has consumed, also speak to us as designers, planners, historians, and theorists. Susan Glasser, the New Yorker’s Washington correspondent, recently recounted that in her first job out of college working on Capitol Hill as a reporter for Roll Call Newspaper, every time she walked into the Capitol building it had awed her. The building’s solidity and its spaces inspired, utterly resonating with its civic mission. How often does someone refer to buildings that way today? Successful design (architecture, landscape, urban design, information design, product design) resonates. That doesn’t mean that it has to look like the U.S. Capitol—our world is a whole lot different from what it was in 1792. But it does mean that we have to consider the effects of what we do, and how we shape the world. Even if right now I’m challenged to find much to be optimistic about, I am unswerving in my conviction about our role. Toward that end, we have an extraordinary array of classes this semester intended to engage us in this work: courses looking at how housing has been affected by changed notions of family, changed practices of the workplace, and changed expectations about climate impact. We have courses laying the grounds for design justice. We have courses positing the impacts of neoliberalism, of material extraction, and of symbols, ranging from confederate monuments to the national park service’s monuments. We have courses covering a dizzying range of techniques, ranging from gaming technology to optical strategies to acoustic ones. We’re looking at materials: their lifespans from extraction to building units; their agency; their heterogeneities; their burning; and their symbolisms. We’re looking at Tar Creek, Oklahoma; Sao Paolo, Brazil; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; Tokyo, Japan; Harvard Square, and Nantucket Island. Despite having fewer students this semester, we have as many if not more courses than we’ve ever had. In response to feedback from students and the Innovation Task Force, we have committed this semester to capping studios to 10 people and capping seminars and limited enrollment workshops at 12 to ensure a better “Zoom world” for everyone. We have also reworked the class schedule—the Academic Affairs staff, working with the faculty, deserve a lot of thanks for this huge effort—to ensure that classes better accommodate the 14 different time zones we find ourselves teaching to. Smaller classes ensure stronger conversations—we even have a seminar devoted to that topic, “Talking Architecture,” focused on the art of the interview. Having witnessed the utter collapse of conversation and communication at the hand of those who believe that simply repeating falsehoods with greater volume or greater social media spread will somehow make them true, nothing could be more urgent right now than real conversation. I’ll be continuing my weekly office hours this semester, and I look forward to those conversations as well. To facilitate even more conversation within the school, we’ll be launching a new, internal website in the coming weeks. Called GSD NOW, this website can be understood as a digital Gund Hall, and will give everyone a direct window onto so much of the activity happening across the school at any given time. It will also include virtual “trays” that encourage formal and informal collaboration. Stay tuned for more details, but for now I can say that I’m super excited by it. GSD NOW will stay with us well past the pandemic as a source for information and collaboration within the school. And speaking of collaboration and conversation, if you weren’t tuned into the launch of Prada’s Fall Winter 2021 Menswear collection on Sunday morning, I encourage you all to go to the website. The runway show was followed by an intimate online conversation between a selection of students across the world with co-creative directors Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons. It was a remarkable acknowledgement of the value of all students, the up and coming creative generation. The GSD was represented by Celeste Martore, Ian Erikson, and Isabel Strauss. Many thanks to Assistant Professor Sean Canty for making that happen on very short notice. And as always, we have an incredible roster of lectures, conferences, and conversations in our public events calendar this term. See what happened? Just talking about what’s going on this semester has brought my optimism back. Indeed, while we have some seemingly insurmountable challenges right now, I’m really excited by what’s going on this spring—it’s all giving 2021 a good horizon. I want to end on a very personal note, though not related to me. Determined not to let 2020 go down in history as the worst year ever, Assistant Professor Jacob Reidel and his partner Laura took it upon themselves to end 2020 on a positive note. Characteristic of his talents as a writer, Jacob tells the story perfectly—you should hear it from him directly, but I’ll just share a couple lines: “Thanks to New York City’s ‘project cupid’ it became possible to meet with a clerk over Zoom. I’ll admit that jumping into a Zoom with the City Clerk on a random workday sandwiched between our own back-to-back work Zoom meetings was a whole new level of dissonance for us, but certainly special and memorable in its own way. Once we had that precious PDF license in hand, we only had until December 22 to complete the marriage with an officiant before it expired. We snuck an officiant, a laptop, and Laura’s parents into the old unused Williamsburgh Savings Bank Hall downstairs from our apartment, loaded up Zoom, exchanged rings, said our vows, smashed a glass, and got married!” I suppose that I should note here that I don’t condone breaking into spaces, but the story does continue (again, quoting Jacob): “and yes, at one point a doorman caught us using the space, but when I explained to him what we were up to, he immediately melted and said ‘let me get the lights on for you!'” A picture, a space, and a happy couple says a thousand words. Congratulations to Jacob and Laura and cheers to everyone for a light-footed and dance-filled 2021!In Cotton Kingdom, Now, Sara Zewde retraces Frederick Law Olmsted’s route through the Southern states

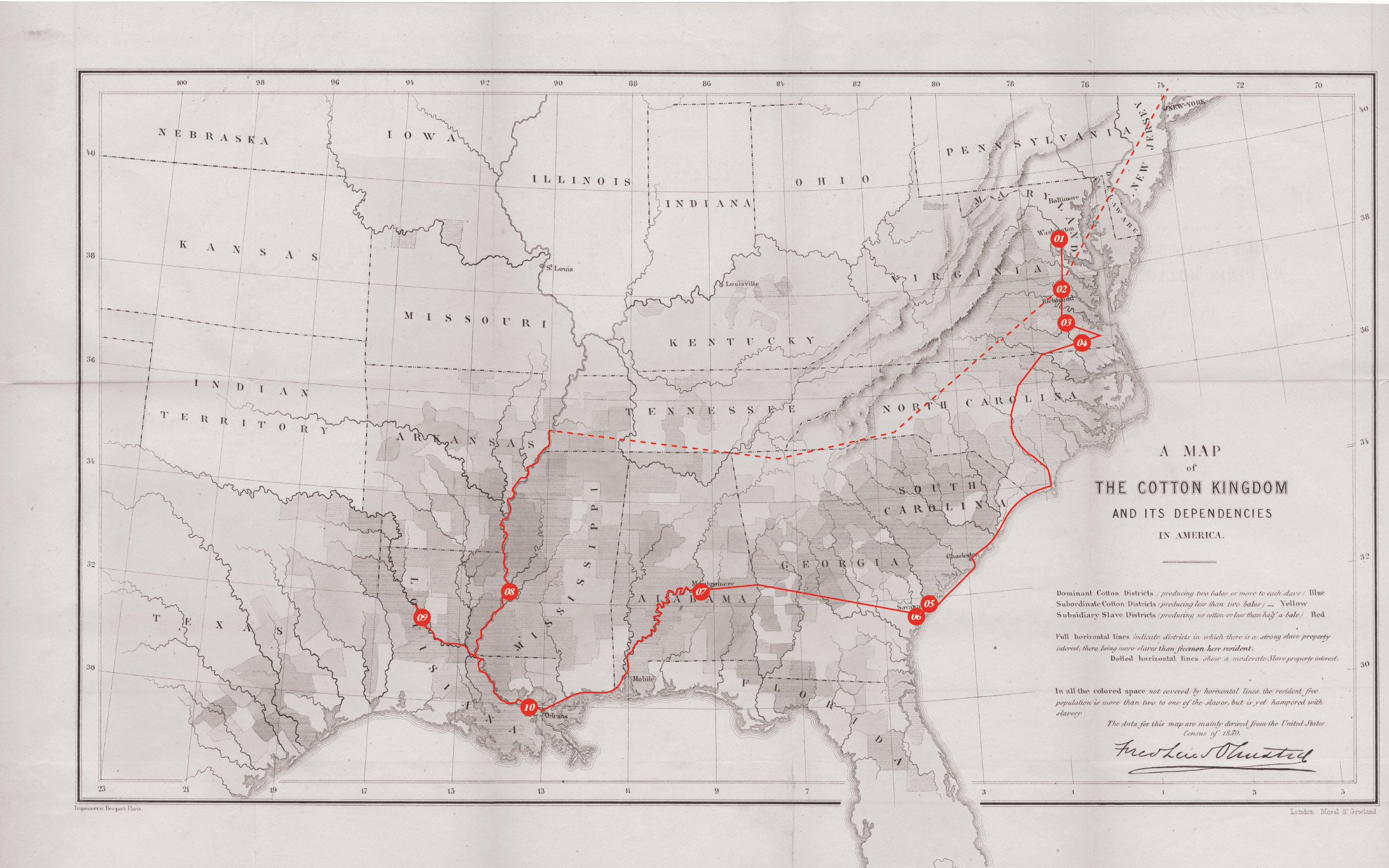

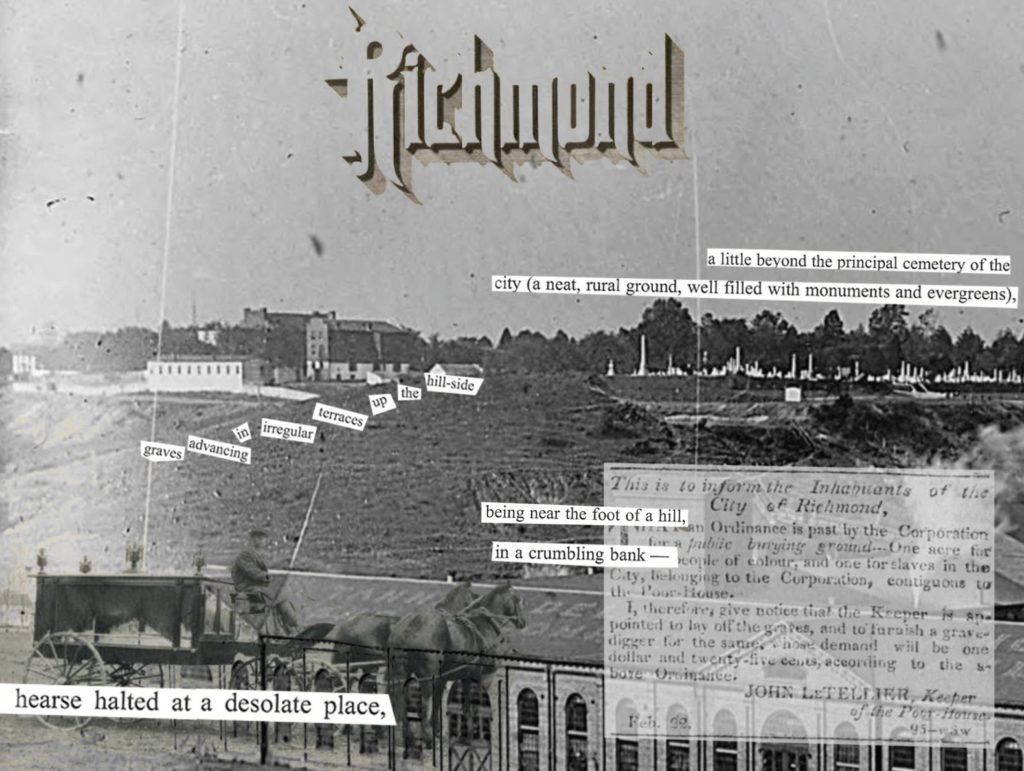

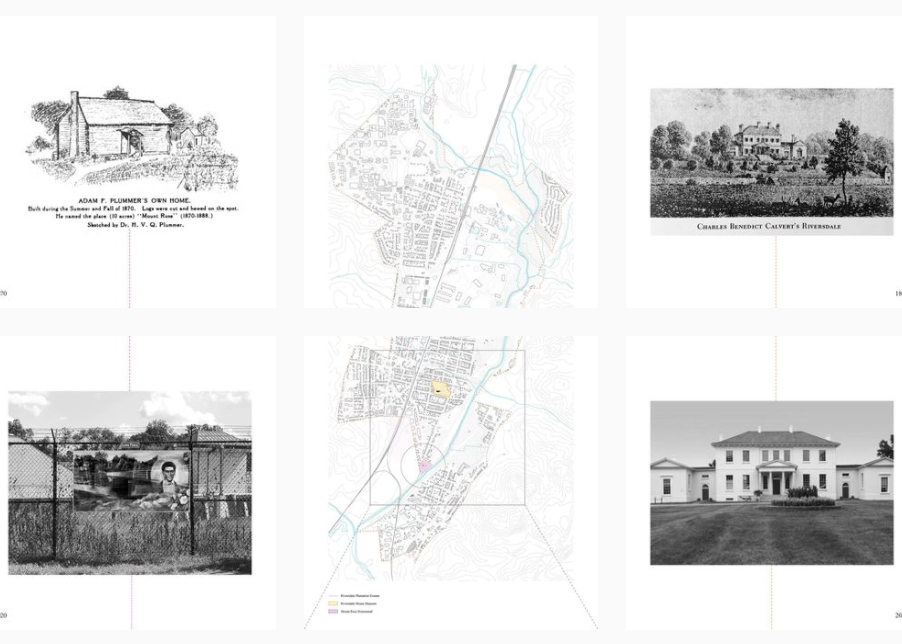

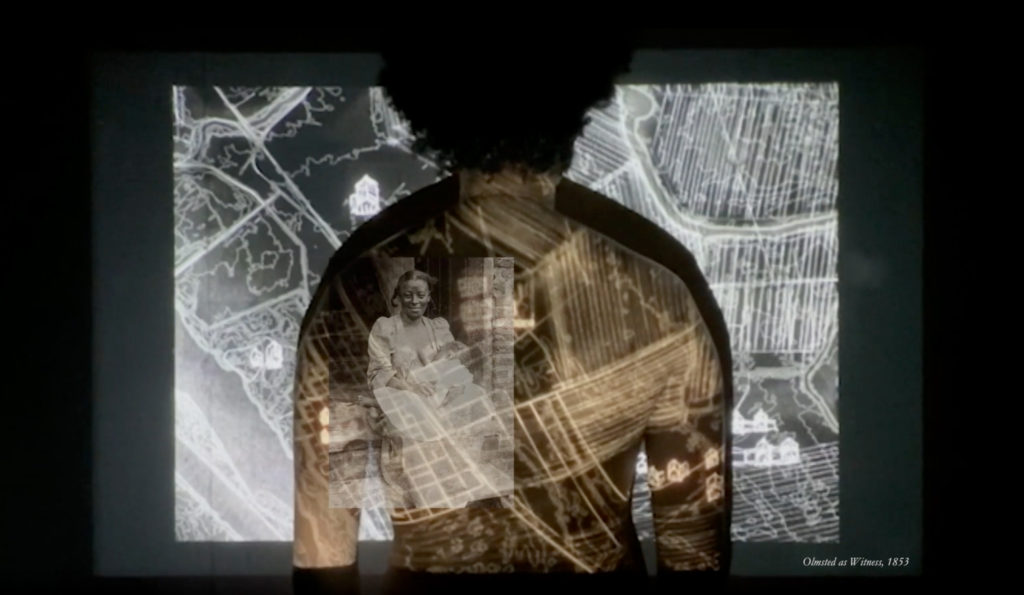

“The mountain ranges, the valleys, and the great waters of America, all trend north and south, not east and west,” says Frederick Law Olmsted in the introduction to his 1861 book, Journeys and Explorations in the Cotton Kingdom. “An arbitrary political line may divide the north part from the south part, but there is no such line in nature—there can be none socially.” Long before Olmsted mulled over the landscape of Central Park or pondered the potential of shared green space in the urban fabric of American cities, the father of modern landscape architecture was a curious 30-year-old unsure of his purpose. In 1852, following travels from China to England, where he came to understand the complex relationship between landscape and class, power, ecology, and identity, Olmsted was dispatched to the Southern slave states by the New York Times. For the next two years, against the volatile backdrop of the Compromise of 1850—five bills that served as a temporary truce on slavery and territorial expansion after the Mexican-American War—Olmsted reported on the cultural and environmental qualities of the region in scintillating detail. He traversed the networked web of slavery, society, and economy, and unpicked the myriad ways that these forces played out in the sweeping landscapes of the American South. Across two trips, Olmsted visited tobacco plantations in Virginia and the Great Dismal Swamp of North Carolina. He happened upon slave burial grounds in Savannah, Georgia and journeyed the Emigrant Road of East Texas to the borderlands separating the US from Mexico. He witnessed Black burials outpouring with song and emotion; he also saw the hanging of an enslaved woman who had killed her own child, for whom she feared a life of unending suffering. He spoke to both enslaved people and slave owners, abolitionists running free-labor plantations and racist drunks in small-town bars to probe the heart of the South’s cotton complex: to not only describe the region, but to carve out a space for a more nuanced understanding of the South in order to find common ground and a path to abolition. Olmsted remained committed to his research on the Cotton Kingdom throughout his career as a landscape architect, even stepping down from his demanding position as superintendent of Central Park to rewrite portions of the text ahead of its 1861 publication. His research methodology, visceral narration, and sensitivity toward the South and its many discrete agents remain powerful tools for reading the built landscapes of past and present. And this proposition is precisely where Sara Zewde’s Fall 2020 seminar “Cotton Kingdom, Now,” begins.

Collage by Charles Burke and Caroline Craddock depicting historic conditions of the Second African Burial Ground as described by Olmsted

Google Maps pinpoint for the Mount Rose Homestead in Maryland by Rachel Coulomb and Cynthia Deng

Instagram for Mount Rose Homestead by Rachel Coulomb and Cynthia Deng

Video still from Aria Griffin and Kanchan Wali-Richardson’s “From Womb to Womb”

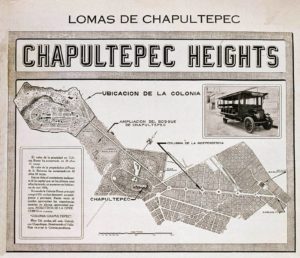

Mexican Cities Initiative in 2020: Essays, Conversations, and Events

Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Mexican Cities Initiative (MCI) aims to guide, through research, the shifting urban landscape of Mexico. In order to aid this urban transformation, research done with the MCI is made entirely public on their website to engage various current and future collaborators into the conversation. MCI also publishes other coursework, faculty projects, and student research to their public archive that is related to Mexico. Student research is supported by an annual summer fellowship and by partnerships inside and outside of Mexico. The initiative is advised by Diane Davis, Charles Dyer Norton Professor of Regional Planning and Urbanism, alongside the MCI advisory board. The past year brought a robust and exciting array of essays, conversations, and events to the MCI platform. The following are excerpts from some of MCI’s 2020 offerings.Aron Lesser Chats with Lorenzo Rocha about Public Spaces and Urban Planning Trends in Mexico City

Lorenzo Rocha: “Currently there are two main trends in Mexico City’s urban development. The first one is an outstanding re-densification of traditional neighborhoods in central areas and the second is the vast creation of new land subdivision in peripheral zones both for affordable or expensive housing. The densification process, that affects the three neighborhoods referred to in the text, takes advantage of preexisting conditions to generate value by designing taller buildings in the traditional urban fabric, further diversifying them. The new peripheral neighborhoods are generally monocultural and dependent on private and public mobility. They are the answer to our massive necessity of housing and security, which the original urban fabric can no longer provide.” Keep reading…

Lorenzo Rocha: “Currently there are two main trends in Mexico City’s urban development. The first one is an outstanding re-densification of traditional neighborhoods in central areas and the second is the vast creation of new land subdivision in peripheral zones both for affordable or expensive housing. The densification process, that affects the three neighborhoods referred to in the text, takes advantage of preexisting conditions to generate value by designing taller buildings in the traditional urban fabric, further diversifying them. The new peripheral neighborhoods are generally monocultural and dependent on private and public mobility. They are the answer to our massive necessity of housing and security, which the original urban fabric can no longer provide.” Keep reading…

Feike de Jong Undertakes Photojournalistic Walk of the Tijuana/San Diego Border

Feike de Jong Undertakes Photojournalistic Walk of the Tijuana/San Diego Border

“Feike de Jong has begun BORDE(R), a photojournalistic walk of the Tijuana/San Diego border. The project explores Global South-North relations by observing the nexus of these cities’ geopolitical—and cultural—boundaries. Paying close attention to urban planning and design, Feike’s approach is rooted in his belief that city borders deserve more attention because they reveal urban realities that city centers may not.” Keep reading…

Mexican local government’s interventions against COVID-19: virtues and flaws

The COVID-19 health crisis creates opportunities to analyze state government activity in Mexico. The social and economic impact faced by each of the country’s state governments demonstrates their responses to the cultural, social, and economic particularities of each locality, but also to their institutional capacities to respond to these growing demands. In this sense, the Mexican case has detonated the unrest of the past, making visible the complications that have historically existed in shaping the federalist puzzle, which should be autonomous and able to exercise its capacities to meet the demands of the moment. Keep reading… Kiley Fellow Lecture: Seth Denizen, “Thinking Through Soil: Case Study from the Mezquital Valley”

Kiley Fellow Lecture: Seth Denizen, “Thinking Through Soil: Case Study from the Mezquital Valley”

Seth Denizen is a GSD Kiley Fellow and design practitioner trained in landscape architecture and human geography. In his lecture “Thinking Through Soil: Case Study from the Mezquital Valley”, which took place on September 21, 2020, Denizen explores the relationship between land politics in the Mezquital Valley and Mexico City. He discusses both his research and the work that GSD students produced in conjunction with UNAM students in a studio course focused on the region. Watch the lecture…

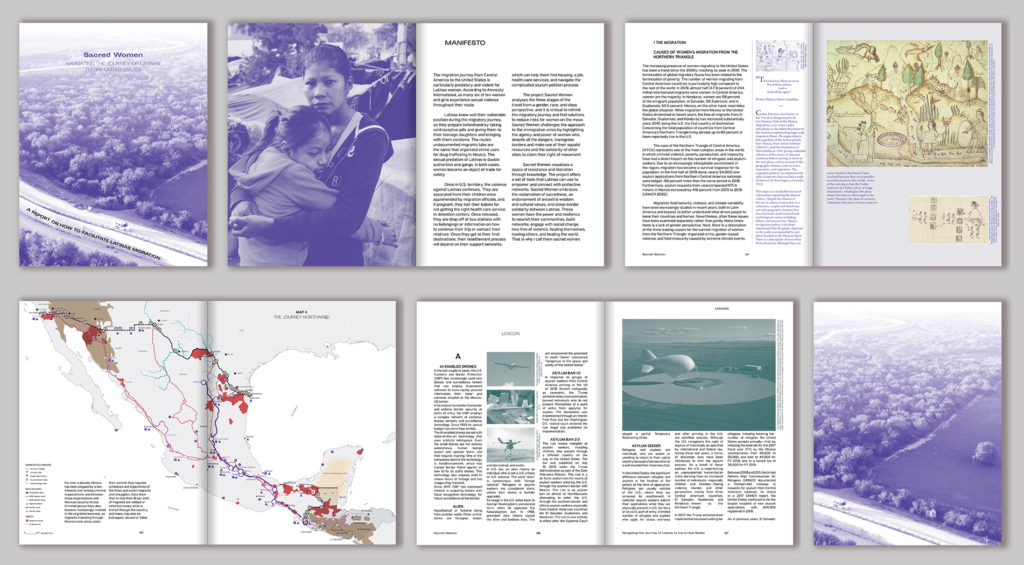

Navigating the Journey of Latinas to the United States

Carolina Sepúlveda: “While migration from Mexico to the United States diminished in recent years, the number of migrants from Central America has increased substantially since 2010[1]. As a result, Mexico has consolidated as the primary transit route for migrants from the Northern Triangle countries, including El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The migration journey through Mexico is particularly violent for women[2]. At the different stages, women are subject to extortion, human trafficking, sexual violence, and even murder in the hands of gangs and organized crime groups. The paths and tactics used by women on the move present an unstable and shifting landscape reinforced by anti-migration policies and criminal groups’ presence along the routes.” Keep reading… Del Temblor al Arte

Del Temblor al Arte

Antonio Moya-Latorre: “Artists’ responses to the earthquake in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec are a perfect example of how art can contribute, in an extreme situation like the one triggered in 2017, to expand community awareness by leveraging the potential of local culture.” Visit the exhibition…

Oaxaca – Beyond Reconstruction

“Harvard GSD faculty and students published a report based on two years of research and studio practice focused on Oaxaca, Mexico after its devastating 2017 earthquake. Based on work with partners at MIT and elsewhere, and through comparative reflection on Chile’s disastrous earthquake a few years prior, the contributors to this publication analyzed what went wrong in the initial disaster recovery in Oaxaca and proposed alternative frameworks for moving forward.” Keep reading…Remembering pioneering Black architect Donald L. Stull (1937–2020)

The Harvard Graduate School of Design honors Donald L. Stull, FAIA (MArch ’62), a groundbreaking architect who led noteworthy, award-winning, transformative design projects and who supported and amplified the unique contributions of Black architects and designers. In a remarkable career, Stull founded two firms that were owned and led by Black architects, through which he would shape cityscapes, harmonize architecture and social change, and inspire countless colleagues and mentees.

Stull died on November 28, 2020, at his home in Milton, Massachusetts. He was 83 years old.

Stull was born in Springfield, Ohio, on May 16, 1937, and took an early interest in architecture while accompanying his uncle, a bricklayer, to construction sites. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in architecture from Ohio State University in 1961, then received a master’s in architecture from Harvard GSD in 1962. In 1970, he received the Distinguished Alumni Award from Ohio State; Boston Architectural College awarded him an honorary degree in 2011.

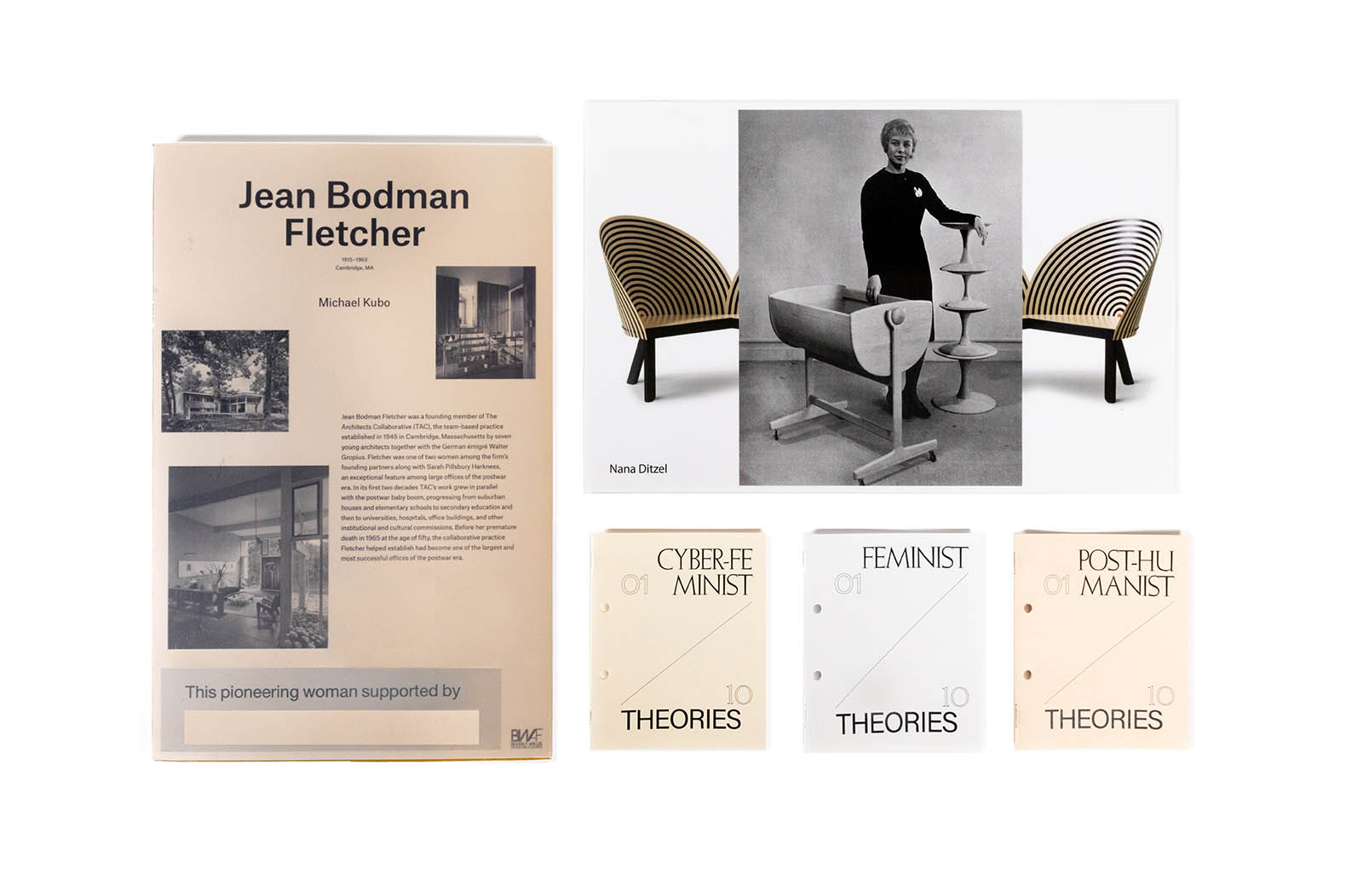

After graduating from the GSD, Stull would go on to work with the Architects Collaborative in Cambridge, co-founded by Walter Gropius, as well as Samuel Glaser Associates in Boston. In 1966, Stull established Stull Associates, at a time when, it is believed, there were only a dozen Black architects in the United States. In 1969, Stull hired M. David Lee, who was a GSD student at the time; the firm became Stull and Lee Incorporated in 1986.

“There was a confidence about him that radiated. And people liked to listen to him,” Lee told

the Boston Globe. “He was so skillful in terms of his thinking and his ability to draw and frame design opportunities that I think people enjoyed being brought into that discussion.”

Stull and Lee Incorporated grew its practice from residential design to major building projects across Boston, earning awards at the highest level of the profession. Stull and Lee received the American Planning Association/Massachusetts Chapter Social Advocacy Award, and earned the American Institute of Architects Honor Award for Architecture as well as the Boston Society of Architects Honor Award for Design for their Ted Williams Tunnel design. Stull and Lee coordinated the design of nine of the city’s Orange Line subway stations, as well as a miles-long park running above them; this work earned them the Presidential Design Award from the National Endowment for the Arts. In particular, Stull and Lee designed the Orange Line’s Ruggles Station, which would emerge as a Boston landmark; the vaulted walkway at the Ruggles Station, connecting Columbus Avenue and the Northeastern University campus, was a particular point of pride for Stull.

Among other projects, Stull and Lee designed Boston’s Roxbury Community College and the Harriet Tubman House, and were lead architects and master planners for the $747 million Southwest Corridor project. In 2004, Stull discussed

his design philosophy behind the Roxbury Community College project:

I think a bit philosophically in the way I think about design. If one is going to design an educational facility, it’s my view that you first need to ask and answer questions regarding, what is education, what is learning? And then begin to evolve a design that’s responding to and answering those questions. When I did Roxbury Community College, the question for me at the time was that learning… is an interactive process, that it’s an interaction between student and books, student and teacher, teacher and teacher, student and student, student and environment.

For example, in a learning objective in design, we know that from a physical point of view, from a scientific point of view, the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. Therefore, the most efficient way to get from one place to another place is that way. However, if that is in a learning environment, the critical question is not how quickly you can get there but what happens to your mind on the way? And so that may not be the shortest distance or the fastest way to get there. You may decide to take the line through a labyrinth of learning experiences.

That’s one of the reasons Roxbury Community College is not one big mega structure building, but a campus. And so I looked for ways to create the, the places within that environment where one could enjoy the interactive process of learning at very many different levels. We’ve got some sculptures sitting in different places, places where you can sit outside quietly and contemplate the places and all the buildings wherein that kind of interactive process can happen.

“He was a brilliant draftsman, a wonderful designer, and a thoughtful, philosophical practitioner,” Lee observes in the Boston Globe. “He enjoyed the respect of his peers.”

Alongside built work, Stull devoted his focus and energy to amplifying the contributions of Black architects and designers. Of note, he helped establish the New DesigNation conference; the inaugural session in Philadelphia in November 1996 gathered over 500 Black designers to examine and address the issues faced in the design professions.

Stull leaves two daughters, a son, a sister, and two grandchildren. He was predeceased by his mother Ruth Callahan Stull and his father Robert Stull of Mississippi, and longtime companion Janet Kendrick of Roxbury, Massachusetts.

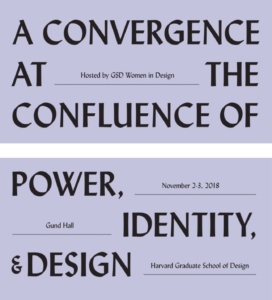

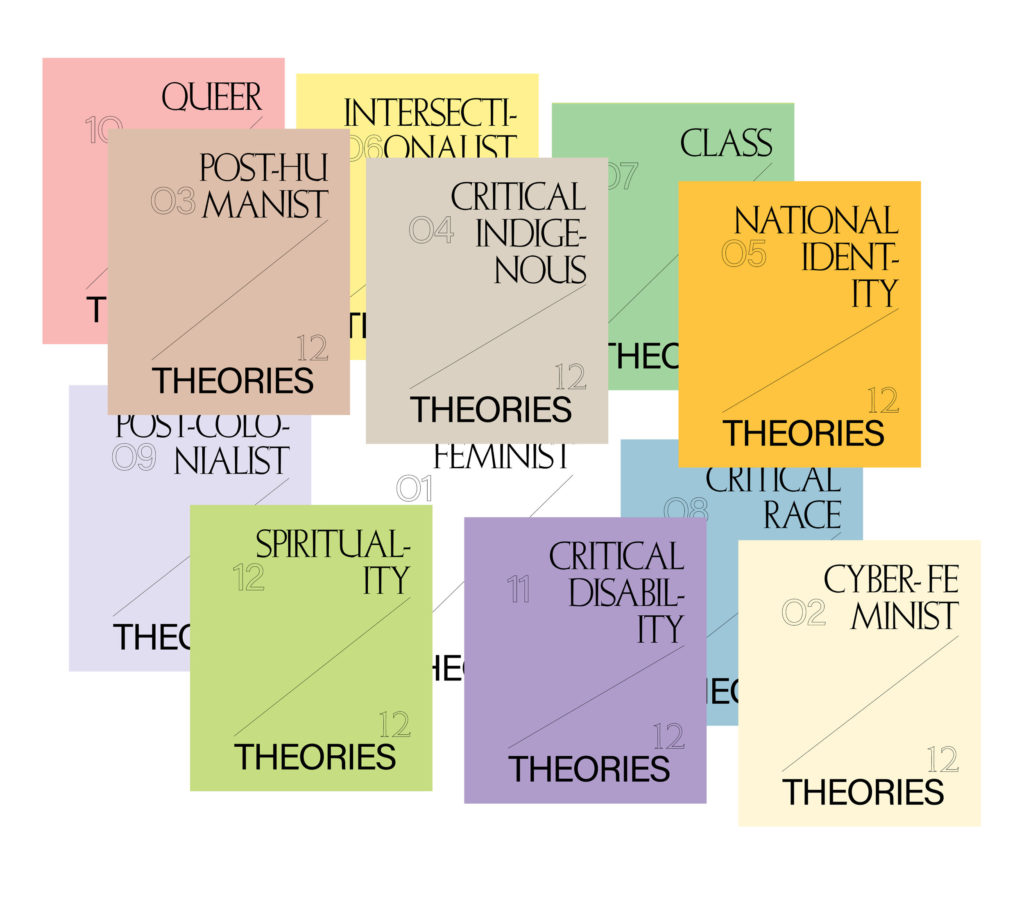

Womxn in Design on shifts in design pedagogy: “The conditions in which we learn become the conditions we practice and reproduce.”

It’s been almost three years since the #MeToo movement started launching public awareness around the architecture industry’s many fault-lines. While dismantling a culture that has been troublingly hierarchical, sexist, racist, and sometimes predatory is slow, grinding work, the unprecedented events of 2020 seem to be inspiring a kind of sea change at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.

Poster design for the first ever Womxn in Design Convergence conference in 2018

WiD Bib, 2nd Edition: An annotated Bibliography on Identity Theories

Cover of the first Womxn in Design Bibliography

How Not to Write About Design: A guide for anyone looking to move beyond form, space, order, and structure

Architects are often reluctant writers, choosing instead to express themselves in other ways. Perhaps this is because architectural education strongly emphasizes graphic over verbal communication, or because the proliferation of overly complex prose in architectural theory engenders distaste for writing among architects. There are many reasons, but one convincing argument is that it is the result of intentional neglect—a symptom of modernist thinking in architecture. Adrian Forty argues, in Words and Buildings, that modernism developed a deep suspicion, even a “horror of language,” in all of the visual arts. “The general expectation of modernism that each art demonstrate its uniqueness through its own medium, and its own medium alone,” he says, “ruled out resort to language.” In other words, modernists insisted that their work should speak for itself. Modernism therefore developed a very limited vocabulary (Forty lists “form,” “space,” “design,” “order,” and “structure” as its key words) and a distinctive “new way of talking about architecture” that was extremely taciturn. It made the difficult task of writing almost superfluous for architects, and they simply chose not to do it.The general expectation of modernism that each art demonstrate its uniqueness through its own medium, and its own medium alone, ruled out resort to language.

on modernism’s “horror of language”

[Writing] opens their mind up . . . . It’s a way for [students] to discover their own architecture.

on the design exercise of writing

Architects read space, and moving ‘through the process of understanding how to write space in all three dimensions.’

noting studio observations on the comprehension and expression of architectural space

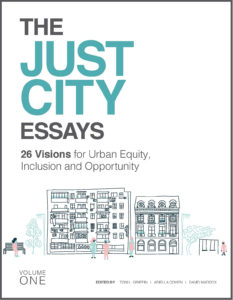

Excerpt: A Democratic Infrastructure for Johannesburg, by Benjamin Bradlow

“Five years ago, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Just City Lab published The Just City Essays: 26 Visions of Inclusion, Equity and Opportunity. The questions it posed were deceptively simple: What would a just city look like? And what could be the strategies to get there? These questions were posed to mayors, architects, artists, philanthropists, educators and journalists in 22 cities, who told stories of global injustice and their dreams for reparative and restorative justice in the city. These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays

These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays

A Democratic Infrastructure for Johannesburg

By Benjamin Bradlow

There are two main legacies that define urban inequality in South Africa: housing and transport. Apartheid was not only a racial ideology. It was also a spatial planning ideology.

Johannesburg’s development into a wealthy, white core of business and residential activity, with peripheral black dormitory townships, was a result of specific legislation and government action accountable only to white citizens. Black people were confined to houses in townships that had little economic value. Black townships were synonymous with urban poverty. These houses were far away from business activity and jobs. As population movement controls eroded in the late 1980s, informal settlements began to concentrate next to formal townships. The story of Johannesburg, the financial center of South Africa, can help understand how the struggle to build these connections defines the extent to which Johannesburg can be considered “just.”

Today, Johannesburg offers unique insights into the prospects for other cities in Africa. This is not because most cities in Africa are similar to or are likely to become similar to Johannesburg. But Johannesburg has a basic historical characteristic that resembles that of many African cities: it was planned for inequality. Johannesburg’s uniqueness also marks it as a lodestar for other African cities. It is a meeting point of migrants from all over the continent, and an economic engine of growth on the continent. These flows of people, money, and goods, in and out of the city, mean that the impact of the city is continental.

The notion of a just city in Africa will have to accommodate the extent to which the hopes of earlier generations of social scientists and policy-makers for rural-led development on the continent have now been rendered moot by economic patterns that are both global and local. In Johannesburg, one of the most industrialized cities on the African continent has become a magnet for rural South Africans, and international migrants from other African countries. The primary infrastructural challenge is not only about identifying technical shortcomings or mere numbers of delivery. It is about generating the voice from below to demand that infrastructure reach those who need it most, and to ensure the political will to manage contentious distributional decisions about land and public finances.

I want to show why this is so difficult, and how, in order to make the decisions that are “just,” we need to first make sense of the history that lies behind those decisions. Continue reading on designforthejustcity.org…

Land for a City on a Hill: Alex Krieger’s iconic tour of Boston

Watch as Alex Krieger, professor and former chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design, takes viewers on his iconic tour of Boston. Stopping at locations key to the growth of the city—from East Boston, which was once five islands that were consolidated in the late 18th to 19th century, to the Shawmut and South Boston Peninsulas—Krieger speaks of the historic and contemporary geographical, infrastructural, and racial conditions of Boston, a city in “constant need to create land.”