Winter Reading 2025: Design Books by GSD Faculty and Alumni

In need of new reading for the new year? These recent books by Harvard Graduate School of Design faculty and alumni—published within the past six months and organized alphabetically by title—feature topics from Victorian architecture to geospatial mapping.

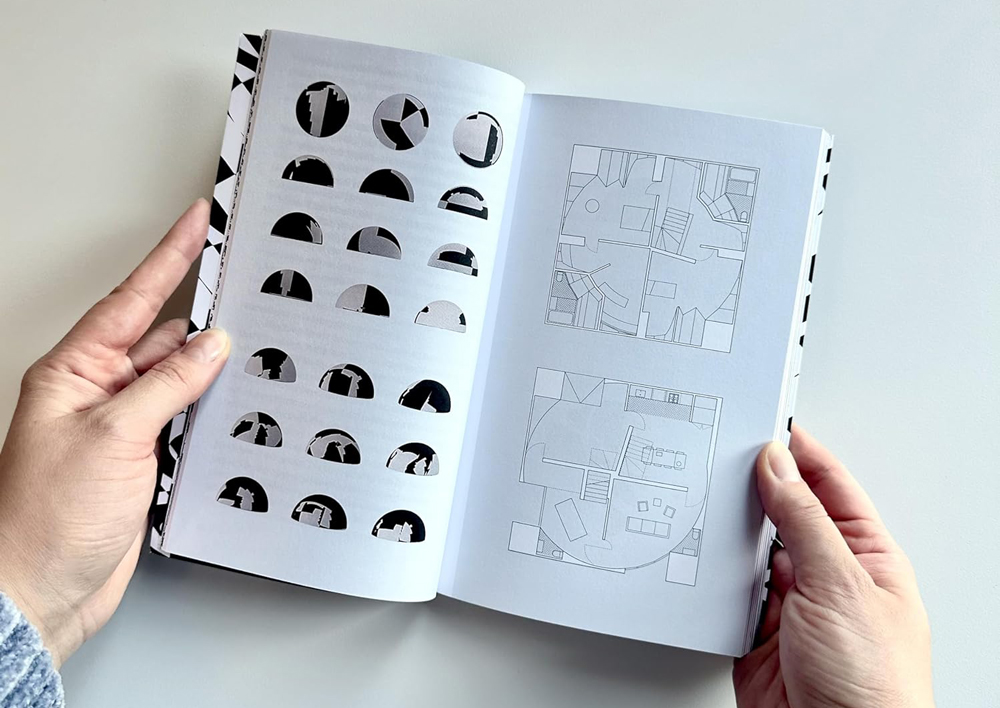

In Also Known As: Uncovering Representational Frameworks in Architecture, Art, and Digital Media (MIT Press, 2024), assistant professor of architecture Michelle Jaja Chang (MArch ’09) ponders relationships between objects and architecture. Drawing on design, media, computation, and art, this book employs texts and images to explore the social, material, and political impacts of architectural systems and design technology.

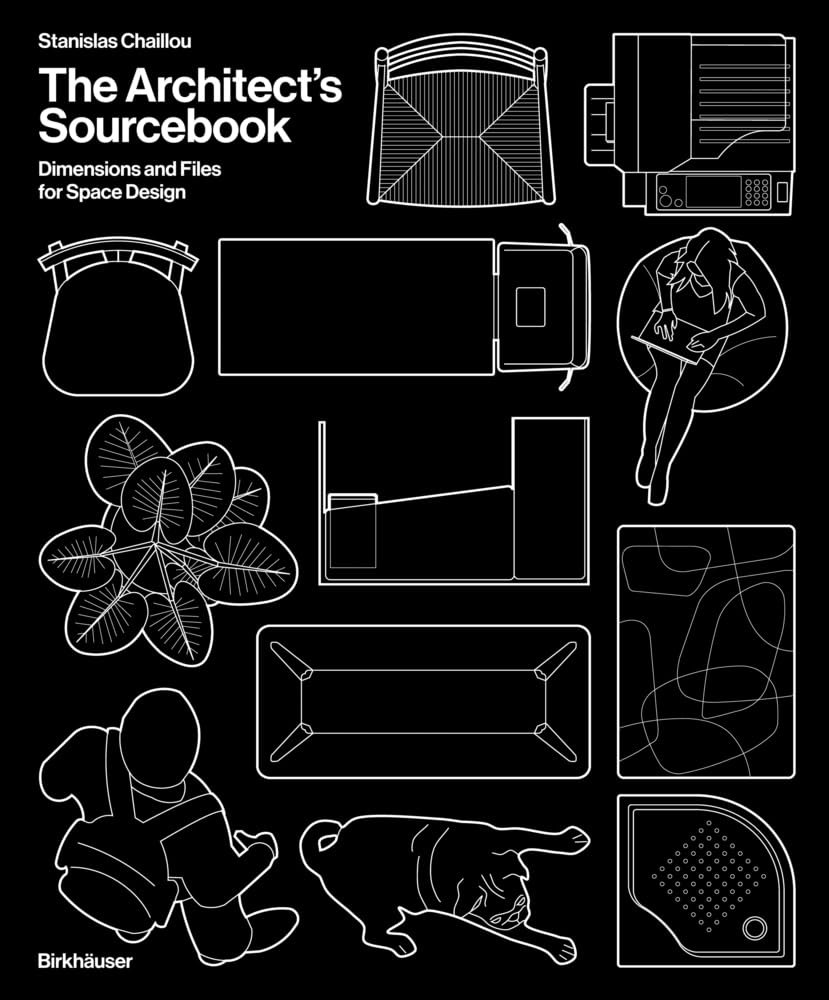

A contemporary architectural manual, The Architect’s Sourcebook: Dimensions and Files for Space Design (Birkhäuser, 2024), written by Stanley Chaillou (MArch ’19), presents a digital repository of typologies, from housing to work to leisure spaces, complete with explanatory texts, general dimensions and guidelines for 2D layouts, and downloadable CAD blocks.

Architecture.Research.Office. (DelMonico Books, 2024), edited by Stephen Cassell (MArch ’92), Kim Yao, and Adam Yarinsky, documents over thirty projects by the editors’ New York–based firm Architecture Research Office (ARO), recipient of the American Institute of Architects Firm Award in 2020. Founded in 1993, ARO is known for engaging, research-driven projects with a clean aesthetic, including the phased renewal of the Rothko Chapel and Campus (ongoing) in Houston; the Brooklyn Bridge Park Boathouse (2018); and the Congregation Beit Simchat Torah (2016) in New York City.

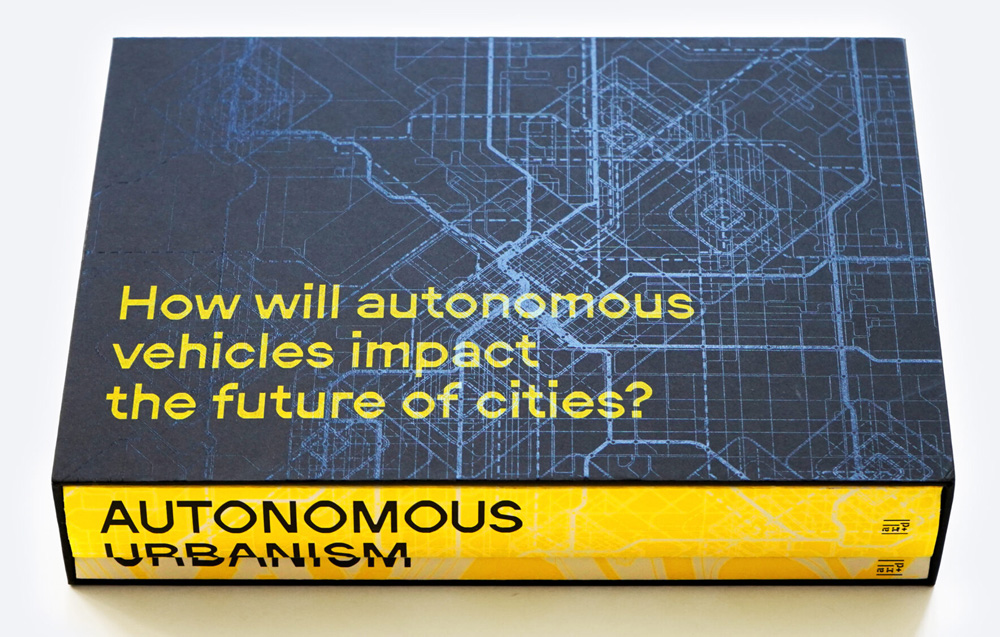

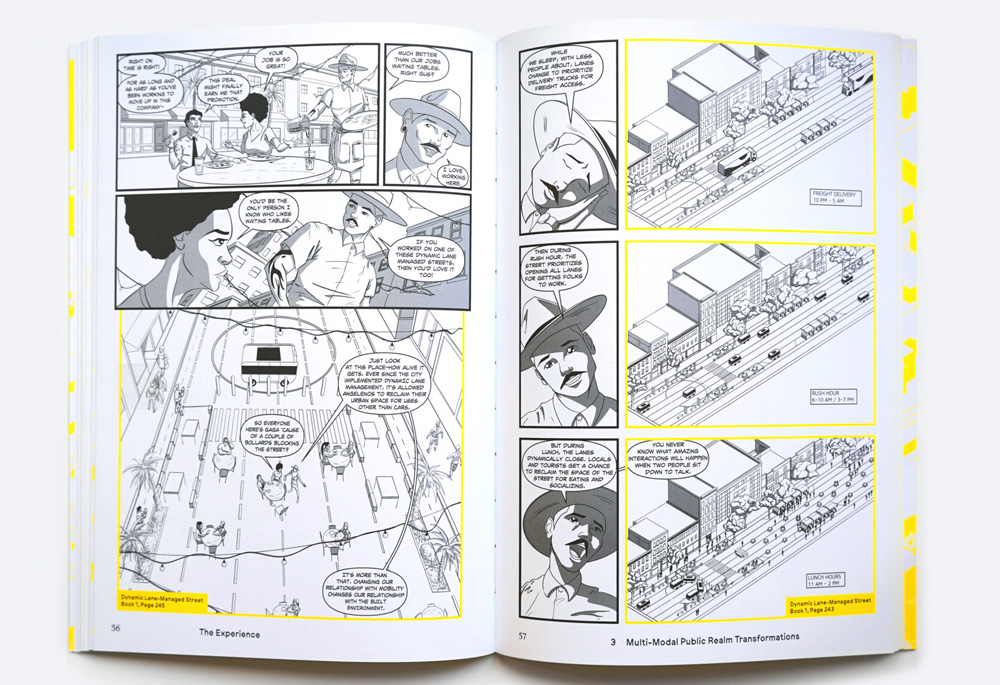

Autonomous Urbanism: Towards a New Transitopia (Applied Research + Design Publishing, 2024), by Evan Shieh (MAUD ’19), explores the latent and transformative impact autonomous vehicles will have on the urban and spatial future of cities. Employing representational techniques of graphic novels, the book explores our recent history of urban transportation and speculates on the typologies and policies that await us with a driverless mobility paradigm shift.

In “Modernism in Three Acts,” published in editor Léa Namer’s Chacarita Moderna: La Nécropole Brutaliste de Buenos Aires (Building Books, 2024), associate professor of architecture Ana María León (MDes ’01) draws on archival documents held at the Special Collections of Frances Loeb Library to explore the architectural context in which Argentine architect Ítala Fulvia Villa designed the monumental Sexto Panteón (Sixth Pantheon) at the Chacarita Cemetery in Buenos Aires.

Juxtaposing an essay by Mohsen Mostafavi, Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design and Harvard University Distinguished Professor, with one written decades prior by the German art historian Max Raphael (1889–1952), The Color Black: Antinomies of a Color in Architecture and Art (Mack Books, 2024) expounds on the relationship between architecture, art, and the color black. Commentary by Swiss architect Peter Märkli and American artist Theaster Gates, along with a broad range of illustrations, offer additional thoughts on contemporary architectural and artistic developments.

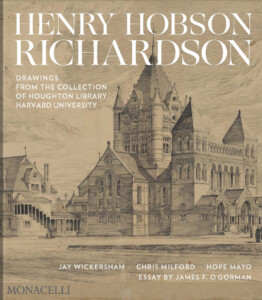

Henry Hobson Richardson: Drawings from the Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University (Monacelli, 2024), by Jay Wickersham (MArch ’84), Chris Milford, and Hope Mayo, presents previously unpublished sketches, renderings, and plans of more than 50 projects by the famed nineteenth-century architect, covering building types from houses and railroad stations to churches, libraries, and civic structures. Essays by the authors as well as architectural historian James O’Gorman shed light on Richardson’s extensive oeuvre and enduring legacy.

With IDEAS–A Secret Weapon for Business: Think and Collaborate Like a Designer (Routledge, 2024), Andrew Pressman (MDes ’94) offers a sensible guide for leaders to incorporate elements of design thinking within their organizations. Relying on case studies and practical techniques for fostering creativity and critical thought, this book provides readers with a framework to encourage innovation and teamwork in all business realms.

Large, Lasting, & Inevitable (Park Books, 2025) by Jorge Silvetti, Nelson Robinson Jr. Professor of Architecture, Emeritus, illuminates foundational moments that have shaped architectural thought throughout the past six decades. Edited by Nicolás Delgado Alcega (MArch II ’20), the book features a selection of Silvetti’s seminal texts alongside discussions with figures of the next generation—including design critic in architecture Mark Lee (MArch ’95), Robert P. Hubbard Professor of Architectural History Erika Naginski, Elisa Silva (MArch ’02), Nader Tehrani (MAUD ’91), and Alfredo Thiermann.

Meet Me at the Library: A Place to Foster Social Connection and Promote Democracy (Island Press, 2024), by Shamichael Hallman (LF ’23), positions libraries as spaces that, when properly conceived and programmed, help build inclusivity communities. Drawing on extensive research and examples from throughout the United States, Hallman highlights the significant role libraries could play in healing the rifts that divide our nation.

Monumental Affairs_Living with Contested Spaces (Hatje Cantz, 2024), edited by Germane Barnes (Wheelwright Fellow, ’21), presents interviews, lectures, and other documentation from the Design Akademie Saaleck’s 2023 symposium, held at the former home of National Socialist ideologue and architect Paul Schultze-Naumberg in Saaleck, Germany. The most recent installment in the dieDASdocs series, this text features interdisciplinary explorations into discriminatory architectural and urban practices embedded within the conception, production, and endurance of monuments.

To Nos Lieux Communs (Fayard, 2024), edited by Fabrice Argounès, Michel Bussi, and Martine Drozdz, assistant professor of urban planning Magda Maaoui contributed a discussion on the Haussmannian “chambre de bonne” worker housing typology at the intersection of historic preservation, climate adaptation, thermal comfort, and health. An essay by Antoine Picon, G. Ware Travelstead Professor of the History of Architecture and Technology, addresses the complex global geographies of data centers.

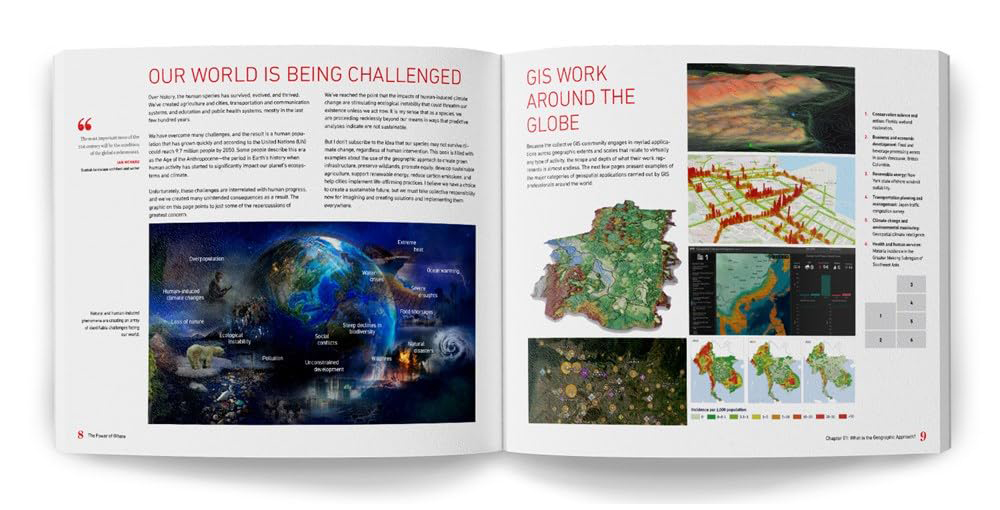

In The Power of Where (Esri Press, 2024), Jack Dangermond (MLA ’69) details the history and advancements of geographic information systems (GIS), presenting mapping as a problem-solving method that allows users to perceive and understanding patterns of all kinds—from spatial to environmental to demographic. Architect and designer Richard Saul Wurman described the richly illustrated book as “a bible of the types of maps, cartography, spatial analysis, and diagrams that can bring our ideas for the future to life.”

Radical Atlas of Ferguson, USA (Belt/Arcadia Publishing, 2024), by Patty Heyda (MArch ’00), probes the planning policies that shaped the St. Louis suburb where, in 2014, racial tensions erupted following the murder of 18-year-old Michael Brown. Using more than 100 maps, Heyda examines philosophical, financial, and design-related forces that set the stage for this violence, prompting readers to consider for whom cities are built and how design impacts everyday life.

Revitalizing Japan: Architecture, Urbanization, and Degrowth (Actar Publishers, 2024) features the work of young architects in Japan who are practicing in ways that respond to the post-growth condition of the country’s shrinking population. Co-edited by Kayato Ota and Mohsen Mostafavi, Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design and Harvard University Distinguished Professor, the book contains texts by architect Toyo Ito and community designer Ryo Yamazaki and photos by Kenta Hasegawa

Humphry Repton’s Pop-up ‘Red Book’ at the Frances Loeb Library

At 36, Humphry Repton (1752-1818) retreated to the country after failing in yet another career. He spent his time doing what he truly loved—painting and writing—while learning from a neighbor about the flora and fauna around him and designing landscape projects for friends: “I am impatient to shew you the alterations in my house and lands,” he wrote. “The wet hazy meadows, which were deemed incorrigible, have been drained, and transformed to flowery meads.” When the renowned landscape architect Capability Brown died, Repton named himself Brown’s successor, coining the title “landscape gardener,” because, he explained, “the art can only be advanced and perfected by the united powers of the landscape painter and the practical gardener.”

Repton propelled himself into his new career with savvy advertising and a singular design aesthetic that relied on his lifelong practices of painting and writing poetry. He became known for the bound “red books” featuring his watercolor landscapes from various vantage points, and ingenious overlays that could be lifted and lowered to show clients the “before” and “after.” The liftable flaps were likely inspired by the widely read pop-up and interactive books made for both adults and children in his era.

The Frances Loeb Library holds one of the approximately fifty remaining red books, “Moseley Hall,” in its Rare Books Collection. Scholar A. Reece argues that the books were an extremely effective marketing technique, especially because Repton’s designs were intended to make the landscape look like an improved but still natural setting. “Although more than one hundred years lie between Repton’s Red Books and Eisenstein’s Piranesi essay, a similar concept of montage can be discovered in both cases,” writes Reese. “This montage ensures that the viewer’s attention is drawn from the images themselves to the difference that opens up between the two motifs … [M]ontage as a means of representation has inestimable value for a landscape designer who, in many of his projects, dispensed with spectacular interventions and instead relied on subtle measures…” Repton wrote many essays in defense of his craft and aesthetic, arguing “that true taste, in every art, consists more in adapting tried expedients to peculiar circumstances, than in an inordinate thirst after novelty, &c … this inordinate thirst after novelty, is a characteristic of uncultivated minds.”

Repton explained that the complexity of his role required “a competent knowledge of surveying, mechanics, hydraulics, agriculture, botany, and architecture, as well as other essential tools and skills:…his effects must be studied by the eye of the painter, and reduced to proper scale with the measurement of the land surveyor.”

While Repton never achieved the same levels of wealth and fame as Capability Brown, editors J.C.L. write in their 1840 biography that, “[Repton] enumerates it amongst his many sources of gratitude to Heaven [that] he was blessed ‘with a poet’s feelings and a painter’s eye,…not only for success in my profession, but for more than half the enjoyments of my life.’”

Repton’s work and legacy have been critiqued both in his own era and by contemporary scholars. Jane Austen refers to him in Mansfield Park as “the archetypal ‘improver,’” writes J. Finch, “who destroys ancient avenues in pursuit of the improved modern landscape.” Edward Eigen, senior lecturer in the history of landscape and architecture at the GSD and MDes Narratives domain head, in his essay on the roots of racist incidents in New York’s Olmsted-designed Central Park, writes, ”While descriptions of ‘Pig Town’ or ‘Stink Town’ were rife with anti-Irish sentiment, the unimproved grounds of this neighbourhood presented precisely the sort of ‘natural defect’ that Olmsted has learned from Humphry Repton must be ‘removed or concealed,’” The Irish immigrants and African-Americans whose farming and livestock spaces were unacceptable to Olmsted were removed by the police, who, Eigen writes, were also to oversee the completed park and arrest anyone they perceived to be misusing it.

—

Daniels, Stephen. Humphry Repton, Landscape Gardening and the Geography of Georgian England. New Haven: Yale university Press, 1999

Eigen, E. (2022). Birds, dogs, and humankind in Olmsted’s ‘Bramble’: a story of Central Park. Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, 42(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14601176.2022.2035164.

FINCH, J. (2019). Humphry Repton: Domesticity and Design. Garden History, 47, 24–38. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26589636 .

Repton, H. (1792). Mosely [sic] Hall near Birmingham, a seat of John Taylor, Esqr. Frances Loeb Library Special Collections, Rare Books. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:46526300$1i .

Reese, A. (2022). Montaged Gardens – On Paper: The Red Books by Landscape Designer Humphry Repton. Dimensions. Journal of Architectural Knowledge, 2(4), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.14361/dak-2022-0406

Repton, H., Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius). (1840). The landscape gardening and landscape architecture of the late Humphrey Repton, esq.: being his entire works on these subjects. A new ed. London: Printed for the editor, [etc., etc.].

Bas Smets Teaches How to Hack Urban Landscapes for a Changing Climate

In the Attica region of Greece this August, says Bas Smets, wildfires ripped through forests left parched by record-hot temperatures, with heat waves starting June 12, earlier than ever before.

“They had to close the Acropolis,” he said, “which is the most visited tourist attraction in Athens.”

By the end of the summer, the fires had claimed one person’s life and left more than 150 acres scorched. The ongoing drought, following Greece’s hottest summer on record, forced residents to surrender tourism income when they couldn’t supply water for their guests. And, this fall, chestnut and olive farmers yielded diminished harvests. Experts warn that Greece’s water crisis will be ongoing.

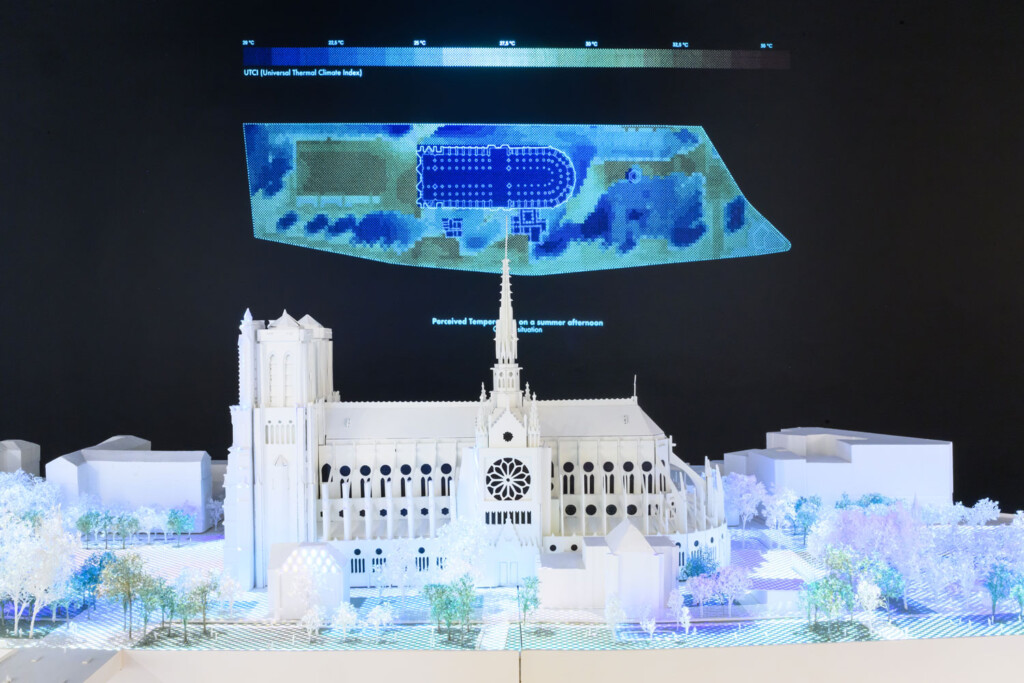

Smets, professor in practice of landscape architecture at the GSD, is at work alongside his students in Athens this semester, developing an intervention as part of his multi-course series on biospheric urbanism, which involves carefully measuring each city’s climate and infrastructure, mapping the climate for the next hundred years, and then “hacking” into the system to create what he calls microclimates, which aid in human and nonhuman survival and, ultimately, mitigate climate change. “Biospheric Urbanism is the study of the built environment as the interface between meteorology and geology,” Smets writes in an introduction to the studio. “It seeks to transform the critical zone between the above and the below, to better adapt to uncertain changes in climate while optimizing the use of underground capacities.” So far, Smets’s courses at the GSD have focused on New York and Paris, operating in tandem with his firm’s projects at Notre-Dame in Paris, Luma Park in Arles, and the Scheldt River park in Antwerp.

As climate change wreaks havoc around the world, says Smets, he believes the solution requires systemic thinking and wide-scale collaboration. Noting common factors in the recent floods in Valencia, Spain, as well as other similar catastrophes in Europe over the past few years, he pointed to how, “the construction of the city restricts the river. So, when we make a design proposals, of course we make it for a specific site and context. But, we are also thinking of it as a systemic concern. How can it be designed in different variations that then could be taken up by other designers, in other cities?”

Building on the work he undertakes at Bureau Bas Smets, he is creating with his students a catalogue of at least 60 scalable hacks that could be adapted worldwide, creating an endless series of urban microclimates that both improve habitability and help fight global warming. “The problem is so big today that the only way out is a collaborative effort,” Smets said. “It’s not about who has the best idea. It’s about, How can we have as many good ideas as possible together? I really believe in that. That’s why I started teaching at Harvard, to share ideas.”

This fall, Smets presented his work in “Changing Climates,” an exhibition and related talk at the GSD that illuminated how deeply he involves his students in his urban biospheres projects. The sense of collaboration that he cultivates in his studio over the course of the semester was evident in the students’ final presentations, as they described how their Athens designs might work in tandem, and how those ideas could be adapted in any city.

A New Kind of Cartography

Smets’s studios depart from the traditional studio format by beginning not with a designated site, but with exploring a city. He wants his students to think critically, finding their own hacks within the urban landscape. The first phase in every project is to create a map, examining, “all the elements of the microclimate, from heat islands to wind speed, humidity, soil, trees, and canopy cover. We try to make a new map of the city by taking into account all the microclimatic elements.” In addition to taking meteorological measurements from across the city, students gather GIS data, study topological and historic maps, look at underground systems like subways and old plumbing infrastructure, as well as parks, building height, and even construction sites.

“I care about cartography, like Alexander von Humboldt and explorers who made their own maps of reality. I want students to make a new map of reality,” Smets said of his approach. “I don’t give them a site, but I ask them to find the site that has a problem. I’m trying to create critical minds that don’t respond to a question, but that ask the question themselves.”

For example, when studying Manhattan in Spring 2023, student Jiyoung Baek (MLA I ’23) found that scaffolding on building facades covers an area equivalent to one third of Central Park. Baek discovered that building owners relied on a loophole to save money: It was cheaper to keep up unsightly scaffolding and pay the city’s fine for failing to remove it, than to pay the cost of removing it and reinstalling it every ten years for required maintenance. Baek proposed transforming each of the scaffolds into green spaces—improving both the aesthetic and environmental quality of the city.

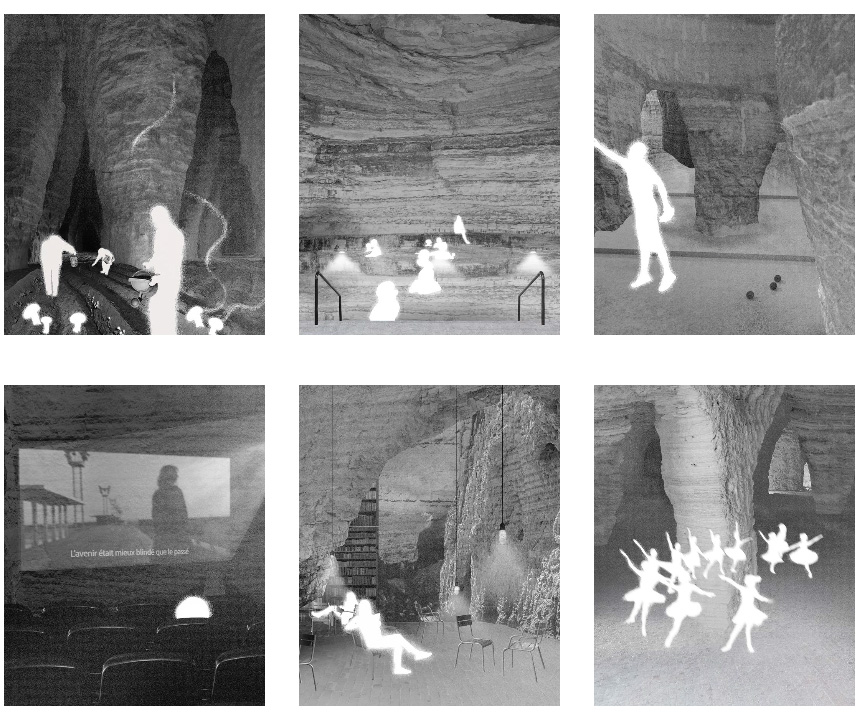

Another student, Parama Suteja (MArch I ’24), looked at the original topography of Mannahatta, as it’s called by the Lenape nation, before it was leveled and developed. Suteja proposed reintegrating the island’s original hills by planting gardens on rooftops and other abandoned spaces. In Paris in the Fall of 2023, Crane Sarris (MLA I ’24) proposed using old underground car parking lots as refuges in the +5 degree future, creating a multilayered underground park, “Musée du Parc,” inspired by the 1867 Paris Exposition. And, Leila Breen (MLA I ’24) hacked one of the abandoned underground quarries in Paris, Bergerye Soutterrain, to create “climate-proof underground spaces along lines 2 and 6 of the Paris Metro,” including space for dancing, reading, swimming, and mushroom agriculture.

Smets argues that, by looking at the city and finding their own interventions, students develop themes that can be applied in other urban landscapes. “They make a project not only for their site, as we traditionally would do, but for the theme that is applied to their site. That way, it becomes systemic.”

Using Succession to Create Microclimates

Once students have found their intervention, Smets asks them to do a close analysis of the site, considering how it will look far into the future as climate change takes hold. “We work with four scenarios: 2 degrees more, in 2025; 3 degrees more, in 2050; 4 degrees more, in 2075; and 5 degrees more, in 2100. That also allows to have a range of proposals that get more and more drastic. It works well to see the gravity of the problem in stages, as well as the necessity of solutions that become more adapted.”

Rather than planning merely for survival in each time period, Smets’ landscapes are made to predict and help advance succession, the natural progression that forests undergo as they develop from open spaces to mature canopies. “How can we accelerate that process?” Smets asked. “How can we use the force of nature to have it come back to the city?”

He applies natural conditions found in the “wild” to atmospheres created in urban landscapes, implementing, for example, water retention systems and forests that would take hundreds of years to grow, to create cooling systems that allow people to enjoy the city while promoting climate resilience. In considering the wind, Smets studies how it would bring sediments, trees, shrubs, and ground cover to the site. As the force of succession proceeds, the slope of the earth and therefore wind patterns would change, and the vegetation would change. For each subsequent succession, the design is pushed further into the future. Three hundred years later, there’s a new ecology. This speculative design process is done in collaboration with pedologists, hydrologists, and ecologists, as well as with climate engineers from Transsolar, which continues to track conditions at the site after the design process, above and below ground.

At Luma Parc des Ateliers in Arles, Smets was presented with a flat, industrial wasteland, and planned a landscape that included 80,000 trees and shrubs, which they planted one by one. In the years after, one hundred of those trees are continuously monitored, as the team returns to the site for visits, helping the site to develop. One species might be found to thrive where another falters, and the team can swap them out. At the team’s Arles site this summer, the perceived temperature was lowered by 20 degrees, in large part due to evapotranspiration—the water trees emit from their leaves during photosynthesis—and the evaporation from the lake the team created. This, says Smets, is proof positive that microclimates can be created in urban landscapes.

Striking Water in Athens

In Athens this summer, temperatures soared 1.6 degrees above normal. “Two degrees,” said Johnny Zhong (MLA I AP ’25), “is the warning before the dominoes begin to fall.”

The immediate solution, he suggested, begins with a sustainable tree canopy, which provides shade as well as the cooling effects of evapotranspiration. Citing a checkerboard of abandoned lots across the city with neoclassical facades that he’d maintain, Zhong illustrated how he could increase the city’s public tree canopy by 138,673 square meters, with underground water aquifers to collect rainfall for the trees.

Thinking at the level of the neighborhood, Carlo Raimondo (MLA I ’25) turned to Greece’s “stoa typology” to transform urban pathways into vine-covered shaded walkways, bougainvillea blooming over formerly scorching sidewalks. Because certain crawling plants, such as Roman hops and wine grapes, flourish in drought conditions that would kill a tree, Raimondo imagined using bollards, installed to protect pedestrians on the sidewalk, to create stoas. This makes Athenian’s existing pathways more useable, and creates new, shaded paths around the city.

Moving further into the climate crisis, to +3 degrees, Muyao Zhou (MLA II ’25) proposed a toolkit—adaptable to any urban context—for collecting rainwater from city roofs and growing rooftop forests, because, as one of the critics noted, “water is the new gold.” Meanwhile, Sitong Wang (MLA I AP ’25) created a citywide shaded walking loop, and Hayden Bernhardt (MLA I ’25) looked below ground, finding limestone pockets underneath abandoned lots. Capitalizing on limestone’s permeability rate of 25-30 percent, he transformed the deposits into wells whose ground-level pools are equipped with misters to cool the area and help vegetation flourish. He noted that the wells could be filled with rainwater collected by Zhou’s rooftops.

The possibilities for inter-reliance among the projects seemed endless, and, Smets emphasized that these projects represent not 11 distinct ideas but a collective intelligence. “Students help each other. We create a community,” he said.

Ultimately, Smets’ concept of urban biospheres, “transforming the critical zone between the above and below to better adapt to uncertain changes in climate,” is grounded in hope. He explained that, working in Athens, a city that’s full of reminders of thousands of years of human history, “it’s interesting to think of the past and the future.”

Smets has an optimistic view of what’s possible, noting that as we move through the effects of climate change, the interventions we make now could be altered later: “The unexplored archeology sites in Athens are amazing opportunities to make carbon sinks. What if we put an anti-root layer to protect those sites, add soil, plant a mini forest for the coming 200 years.” Then, once we’ve survived this phase of warming, people might harvest those trees and excavate the sites to learn about how we lived two thousand years ago. “Maybe the urgency now is to make the planet livable. It’s a whole different way of looking at both the past and the future.”

Flood Control as a Social Movement: Coastal Communities Adapt to a Wetter Reality

As oceans expand and storms intensify, coastal regions face a rising threat: water. Whether due to deluging downpours or surging seas, flooding has increased in frequency for shore communities. Throughout the past two decades, landscape architects and urbanists associated with the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) have explored ways in which oceanfront regions can adjust to this new, wetter reality as coastal adaptation approaches have evolved, shifting from a reliance on hard infrastructure designed to keep water out, to what architects and engineers call nature-based solutions, which often intentionally let water in. Today, GSD-affiliated designers have expanded this trajectory by prioritizing communication and education as essential first steps for adaptation efforts in the struggle with climate change.

The Looming Threat of Sea Level Rise and Storm Intensification

The inaugural report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), issued in 1990, underscored the dangers confronting coastal communities, with sea level rise positioned as a main culprit. Sea level rise stems from global warming, the IPCC explained, which results in higher ocean temperatures that cause water to thermally expand, ice sheets and glaciers to melt, and storms to intensify. A 3-foot rise in sea levels, the report warned, would severely impact coastal regions, “threaten populations in low-lying areas and island countries,” displace millions, expose even more to coastal storm flooding, destroy the built and natural environment, and force the redesign of infrastructure to withstand “flooding, erosion, storm surge, wave attack, and sea-water intrusion.”1 (In recent years, the menace of a 3-foot bump in sea levels has grown to a worst-case scenario of a 6-foot rise by 2100—a fate that will affect thousands of coastal miles and upwards of 800 million people globally.)

Despite the IPCC’s initial warning, the need for coastal adaptation was slow to infiltrate public discussion. Then, in late August 2005, Hurricane Katina roared ashore in southeast Louisiana, bringing storm surge that contributed to the failure of New Orleans’s levee system, inundating 80 percent of the city. Nearly 1400 people died, and flooding took two and a half weeks to recede. Seven years later, Superstorm Sandy’s convergence of weather and tidal patterns overran New York City’s protective infrastructure. High waves and storm surge swamped subway tunnels, knocked out power grids, engulfed at least 50 square miles of the city, decimated area shore communities, and claimed more than 100 lives. No longer nebulous phenomena, sea level rise and storm intensification were rendered strikingly real, exacting a terrible economic, social, and human toll.

For both Katrina and Sandy, infrastructural failures disproportionately affected low-income and working-class communities—a fact that suggested issues of social inequality were built into the infrastructural system itself. This continues to hold true not only in urban settings, but in locations in all stages of development around the world. Likewise, natural ecosystems have been devastated by infrastructure such as levees, sea walls, and pumping stations, which have historically inflicted negative impacts on the environment as well as plant and animal life. With such inequities in mind, architects and engineers have started to seriously rethink dominant approaches to storm water management.

Battery Park, Manhattan, Photo by Timothy Krause. Creative Commons.

From Gray to Green

For centuries, dikes, pipes, and other human-made elements have served as industrialized societies’ go-to tactics for controlling water, either preventing its entry or facilitating its rapid removal. The Netherlands , with a third of its land below sea level, had long been a global leader in such endeavors. By the late twentieth century, Dutch experts began exploring a different approach to water management: they looked to nature, drawing lessons from processes such as permeable ground absorbing water or wetlands buffering against storm surge. Building on these ecological systems, in 2007 the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management launched the Room for the River program to strategically restore rivers’ natural flood plains. The broadened flood plains, achieved through owner-compensated land reclamation and dike relocation, allow rivers to safely accommodate larger volumes of water, which would have previously flooded developed areas. Moving forward, these renewed flood plains will help offset the rising water levels resulting from climate change.

In 2008, the year following Room for the River’s initiation, the GSD embarked on a two-and-a-half-year partnership with Dutch agencies to create the Harvard–Netherlands Project : Climate Change, Water, Land Development, and Adaptation. Characterized by the motto “Water is Our Enemy, Water is Our Friend” and spearheaded by GSD professor Jerold Kayden (MCR-JD ’79), the project involved seminars and option studios in which students and faculty worked with Dutch experts to rethink long-accepted ideas around water management. Instead of focusing on “engineering know-how to build up dikes and improve pumping technology,” they explored “open[ing] cities to the sea in such a way that natural systems can co-exist with human habitation.”2

Elsewhere, coastal adaptation measures that mimicked natural processes were gaining traction. Many submissions to the 2007 design competition for the Governors Island Park and Public Space Master Plan in New York Harbor addressed future rising tides and storm surge, for example incorporating recreational green spaces that could act as buffer zones during flood events.3 A few years later, the Museum of Modern Art staged an exhibition at the PS1 Contemporary Art Center called Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront, featuring interdisciplinary design teams’ proposals to “re-envision the coastlines of New York and New Jersey around New York Harbor and to imagine new ways to occupy the harbor itself with adaptive ‘soft’ infrastructures.”4 On the opposite coast, San Francisco launched an ambitious plan to transform Treasure Island, a former US naval base on a low-lying artificial island adjacent to the Golden Gate Bridge, into a neighborhood with thousands of homes alongside parks, plazas, open spaces, an urban farm, and a commercial town center. This sustainable development, among the first major projects of its kind, established guidance for sea level rise adaptation policy moving forward.5

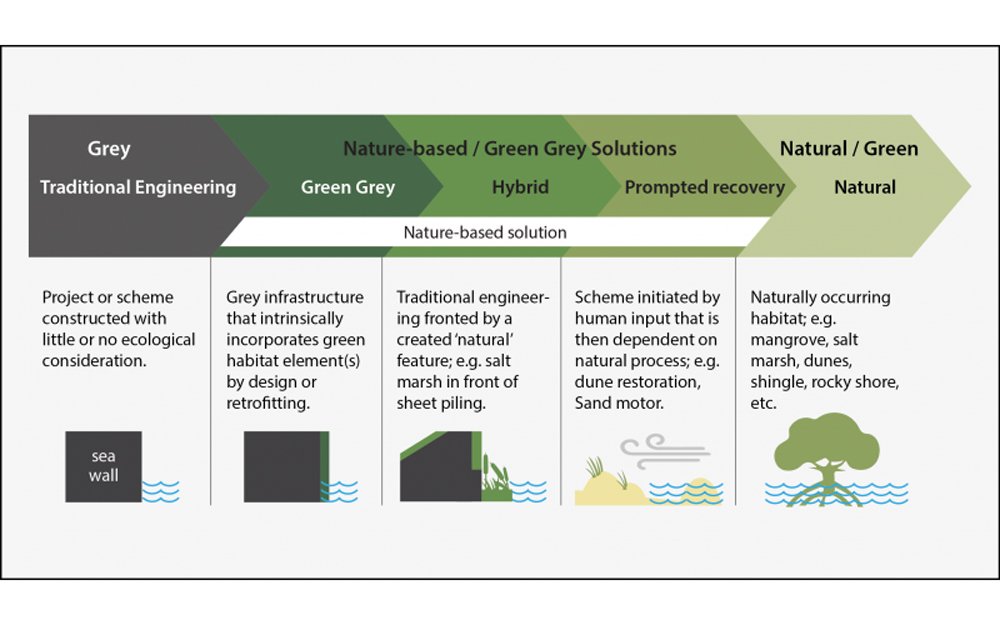

Likewise, in 2010, the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)—the organization responsible for constructing and maintaining water management infrastructure throughout the country—announced the Engineering with Nature (EWN) initiative. Described as “the intentional alignment of natural and engineering processes to efficiently and sustainably deliver economic, environmental, and social benefits through collaboration,” the EWN framework underscored the USACE’s willingness to supplement their engineering tool kit, which classically consisted of hard/“gray” infrastructure, with soft/“green” approaches—what the US Department of Homeland Security’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) now calls “nature-based solutions .” The creation of the EWN indicated that, alongside designers, engineers recognized the value in reconsidering traditional approaches to flood control.

Sandy’s arrival in 2012 accelerated the search for water management solutions that combined gray and green approaches. This hybrid paradigm features in winning projects from the Rebuild by Design competition, initiated in 2013 by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Intended to foster resilience in Sandy-impacted areas through “regionally scalable” yet “locally contextual solutions,” Rebuild by Design operated as a funding mechanism for the initial phase of seven innovative projects.6

This includes the BIG U , designed by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and ONE Architecture & Urbanism, comprising a series of open green spaces that work with berms, deployable walls, and other hard components to serve as flood protection around lower Manhattan. Another project, Living Breakwaters , designed by SCAPE—a landscape architecture and urban design practice run by GSD alumni Kate Orff (MLA ’97 and firm founder), Gena Wirth (MLA/MUP ’09), Pippa Brashear (MLA/MUP ’07), Alexis C. Landes (MLA ’10, also a lecturer at the GSD)—with Parsons Brinckerhoff, involves artificial breakwaters that shield Staten Island’s southeastern coast from storm surge and wave action. Constructed of stone and concrete, the partially submerged breakwaters reduce beach erosion while providing habitats for oysters and other marine life. Currently both the BIG U and Living Breakwaters are advancing through multi-phased construction, demonstrating a distinct progression from water management through hard engineering (such as New Orleans’s levee and pump system pre-Katrina) to approaches that incorporate green processes.

Coastal Adaptation as a Social Movement

Since the Harvard–Netherlands Project concluded in 2010 and Sandy wreaked havoc in 2012, discussions around coastal adaptation and storm water management at the GSD have followed a similar path from gray to green, hard to soft, with programs, studios, and initiatives stretching from Canada to the Philippines, Denmark to China. Recently, the GSD has advanced the conversation by foregrounding community engagement as a necessary precursor to developing water management strategies. In other words, GSD-affiliated practitioners are considering coastal adaptation as a social movement as much as an infrastructural program. This fall, amidst offerings that address coastal adaptation and resilience around the globe, the emphasis on sharing knowledge with and learning from residents of coastal communities is clearly visible in two courses that focus closer to home: Rockaway Peninsula, New York; and Portland, Maine.

Residents of the Rockaway Peninsula, which juts from the southwest corner of New York’s Long Island, have yet to fully recover from Sandy. And with increasing land values, problematic rebuilding practices, and near full salt-water inundation predicted by 2100, life on the barrier island is not getting easier. This convergence of forces prompted Ed Wall—professor of cities and landscapes at the University of Greenwich, visiting professor in landscape architecture at the GSD, and a practitioner whose work focuses on spatial equity—to organize the project-based seminar “Rockaway’s Housing Superstorm: Between Rising Waters and Climate Gentrification.” In this course, Wall and his students collaborated with Rockaway residents to design a new public realm throughout the peninsula that connects local housing to the waterfront and provides shared space for recreation, social interaction, and transportation-hub access. With ample community input, the students then developed strategies of adaptation to respond to the rising seas in the coming months, years, and decades.

Wall believes that collaboration between experts and the communities they serve is a prerequisite for successful adaptation interventions. Yet, as Wall notes, “architects, landscape architects, engineers, and the agencies that employ them too often undertake work in a location without spending enough time there.” This results in designs that may inadvertently ignore true community needs and fail to foster the local interest that sustains a project long term. Thus, Wall’s seminar repeatedly engaged with Rockaway residents and community activists, on site and via video conferences; these interactions guided the students as they designed and refined interventions. “This back-and-forth is partly about building trust with the community,” Wall explains, “and partly about supporting the students as they learn to navigate these relationships and recognize the complexity of this type of work. It’s complicated, layered, and messy, and I genuinely believe it must start with these conversations.”

In addition to frequent engagement, Wall advocates community education through regular and honest discussion about future environmental predictions. “There needs to be some way of communicating that our landscapes are changing,” he asserts. “When we have heavy rainfalls or a drought, what does that mean? Where does our water come from, and how are seasonal tides different from daily tides?” For Wall, public awareness about climate science is an imperative, as is clarity about the temporal nature of buildings, cities, and landscapes.

Similar sentiments about communication and education feature in the work of Pamela Conrad, a landscape architect and design critic at the GSD. This fall Conrad (Loeb Fellow ’23) and Michael Blier (MLA ’94) led an option studio titled “Envision Resilience: Imagining a Future Waterfront for Portland, Maine,” part of a larger multi-university design studio and community engagement initiative called Envision Resilience Challenge , sponsored by Remain . Through Conrad and Blier’s studio, the students worked with local stakeholders to develop short-, mid-, and long-term interventions for the city’s downtown Old Port, which experienced two extreme flooding events in January 2024 alone. The studio prioritized community engagement, aligning with Conrad’s belief that “it is absolutely critical to bring the community into the conversation early, and in a safe space.” This begins by establishing a shared common ground regarding climate-related risks.

During the initial meeting with area residents and stakeholders, Conrad’s students introduced neighborhood sea level rise maps and then posed questions: what concerns you the most about these predictions? What’s important to you in this area? Where do you think we should prioritize resources? This knowledge informed the studio’s next step, which involved additional community discussion around adaptation approaches. “We act as facilitators for the conversation and listen deeply so we can hear community members’ ideas,” Conrad explains. “Then we move to the drawing board to transform their ideas into adaptation concepts, after which we return to the community with those strategies. This process leads to more long-term stewardship because community members see their ideas in the visions presented, and they’re the ones who will advocate for these projects over time.”

Among landscape architects, it is generally understood that nature-based adaptations, such as a living marsh instead of a concrete seawall, can address the risks of sea level rise and storm intensification as (if not more) effectively than hard infrastructure—and with accompanying benefits such as reduced carbon emissions and increased cost savings, human health, and biodiversity. Yet, hard infrastructure often remains the norm in coastal adaptation work, in part because there is no way to systematically assess the efficacy of nature-based adaptations. Fortunately, this will soon change. This fall, Harvard’s Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability funded an ambitious project by Conrad and Charles Waldheim, John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture and director of the GSD Office for Urbanization, to develop and distribute an evaluation methodology for nature-based shoreline adaptation solutions. This study aims to educate design and engineering practitioners, highlighting sources of embodied carbon and demonstrating that “low-carbon, nature-based infrastructure can address, rather than exacerbate, the climate crisis,” thereby laying the groundwork for the broader adoption of nature-based adaptation solutions.7

Conrad’s educational efforts likewise extend to international practitioners and leaders. As one of two delegates representing the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA), she recently attended the UN Climate Change Conference in Baku, Azerbaijan (COP29). Here Conrad and Thai landscape architect Kotchakorn Voraakhom spearheaded a workshop for global policymakers and launched their recently completed WORKS with Nature: Low Carbon Adaptation Techniques for a Changing World , a guide presenting 100 nature-based strategies for various contexts—developing and developed countries, urban and rural locations, coastal and inland.8 Conceived as “a low-carbon, nature-based resource for all countries, at all scales, and for all budgets,” WORKS with Nature prioritizes communication and education as a critical next step for climate adaptation, not to mention climate mitigation and ecosystem regeneration, all efforts essential for sustained future life on our planet. As Conrad notes, “We must share our collective stories, lessons learned, and work on nature-based solutions with the global community.” In the end, “we are all in this together.”9

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change: The IPCC 1990 and 1992 Assessments (June 1992), 106-107, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/05/ipcc_90_92_assessments_far_full_report.pdf. Note that sea levels rise and recede at different rates around the globe, depending on an area’s ground-water subsidence, distance from the equator, and other factors. ↩︎

- See Pierre Bélanger and Nina-Marie Lister, “Landscape Disurbanism” option studio course description, https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/course/landscape-disurbanism-depolderization-decentralization-in-the-dutch-delta-region-spring-2010/. ↩︎

- Ed Wall, interview with author, Nov. 6, 2024. All further quotes from Wall come from this interview. Wall was part of the team that established the 2007 Governors Island competition. ↩︎

- “Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront,” Mar. 24–Oct. 11, 2010, Exhibitions and Events, MoMA, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1028. ↩︎

- Pamela Conrad, interview with author, Nov. 8, 2024. All further quotes from Conrad, unless otherwise noted, come from this interview. Conrad worked on the Treasure Island development during her time with CMG Landscape Architects. ↩︎

- “Origin and Impact,” Hurricane Sandy Design Competition, Rebuild by Design, https://rebuildbydesign.org/hurricane-sandy-design-competition/. ↩︎

- “Salata Institute Funds Five New Climate Research Projects,” Sept. 18, 2024, Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability at Harvard University, https://salatainstitute.harvard.edu/salata-institute-funds-five-new-climate-research-projects/. ↩︎

- Jared Green, “At COP29, Landscape Architects Will Workshop Landscape Solutions to Climate Change with World Leaders,” Dirt, Nov. 6, 2024, https://dirt.asla.org/2024/11/06/at-cop29-landscape-architects-will-workshop-landscape-solutions-to-climate-change-with-world-leaders/. ↩︎

- Pamela Conrad, “Introduction: When it Comes to Climate and Biodiversity, How Do We Choose?” in Pamela Conrad and Kotchakorn Voraakhom, WORKS with Nature: Low Carbon Adaptation Techniques for a Changing World (United Nations Climate Change, Nov. 18, 2024), 13, https://unfccc.int/documents/644016. ↩︎

An Advocate for Architecture: Jhaelen Hernandez-Eli

Nearly twenty years after his graduation, Jhaelen Hernandez-Eli (MArch ’06) will return to the GSD this spring to teach a seminar titled “The Art Museum: Typological Trajectories.” Hernandez-Eli is uniquely qualified to address this topic; as vice president of capital projects at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art , he oversees the institution’s $2 billion construction and renovation campaign, which includes the new Tang Wing for modern and contemporary art by Frida Escobedo (MDes ’12). Beyond his course-related expertise, Hernandez-Eli will share additional lessons about his work and the opportunities for owners to support the profession. “What I would love for students to understand is, that while I don’t practice architecture in the traditional way, the advocacy is still of utmost importance. There’s real opportunity for impact.” Rather than design buildings, Hernandez-Eli crafts processes that enable “an appropriate, robust, and rigorous architecture to emerge.”

Hernandez-Eli first arrived at the GSD in 2002, after earning a bachelor of arts in architecture from the College of Environmental Design (CED) at the University of California, Berkeley. The CED afforded him an understanding of architecture grounded in site and program, informed by environmental and social concerns. At the GSD, Hernandez-Eli encountered a different approach to architecture. In first-semester core studio, Scott Cohen (MArch ’85) assigned the “Hidden Room” exercise, a problem that mandates a covert fifth room be somehow obscured within four rooms. Hernandez-Eli found this exercise enlightening, as it exposed him “to the ideas of innovating within constraints beyond site and program and, more radically, of embracing those constraints.”

Over the next three years, a range of faculty—including Nader Tehrani (MAUD ’91), Monica Ponce de León (MAUD ’91), and Toshiko Mori—instilled in Hernandez-Eli additional foundational principles that, two decades later, continue to shape his work. These notions include an appreciation for architecture as interdisciplinary and socially embedded, not separate from the society that constructs it. Hernandez-Eli likewise developed a reverence for architecture and for the architects and craftspeople that make it. And he learned that, if properly positioned, he can design alternative processes within which architecture is produced, thereby bolstering architects, the power of architecture, and society at large.

The idea of designing processes has been instrumental in terms of Hernandez-Eli’s professional trajectory. While not practicing architecture in the traditional sense, he has constructed an impactful role for himself as an advocate for architecture. This began with his time at Diller Scofidio + Renfro, from 2008 through 2017, where he rose to an associate principal managing the studio’s operations and strategy, facilitating cultural projects such as the Museum of Modern Art expansion and the High Line. Hernandez-Eli then shifted from the service-provider to client/owner side, joining the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) as senior vice president, head of design and construction, where he spearheaded projects fostering social and economic equity, including public food markets and the city’s waterfront infrastructure. In 2020, after three years at NYCEDC, Hernandez-Eli moved to The Met where he oversees the design, architecture, and construction of the institution’s galleries, infrastructure, workspaces, and public areas.

At The Met, Hernandez-Eli has guided multiple projects such as the renovations of the Rockefeller Wing (by Kulapat Yantrasast of WHY Architecture) and the galleries for Ancient Near Eastern and Cypriot Art (by Tehrani of NADAAA). He also continues the larger undertaking he initiated with the NYCEDC: using his institutional role to demonstrate the opportunity owners have “to be bold, bringing in new voices and tackling the pressing issues of our time.” Most owners, he explains, approach the commissioning process in a risk-averse manner, choosing established firms with a well-stocked portfolio. Yet, Hernandez -Eli asserts, “if you know how to manage the project and build an infrastructure behind the scenes to mitigate such risks”—for example, pairing a younger architect with an experienced firm—owners can level the playing field for new voices. And while one might argue that customary design competitions offer newcomers a point of entry, Hernandez-Eli would vigorously disagree. “Competitions are terrible!” he declares. “Architects are undervalued and underpaid through that process. It also does not put the client in the best position to make the right decision.”

To illustrate how owners can design a process that supports less established architects, Hernandez-Eli references the example of Escobedo. As the New York Times noted upon her selection in 2022, “Escobedo, 42, is a surprising choice for such a major assignment given that she is relatively young, has mostly designed temporary structures, and is not a household name.” While these attributes might be deterrents for some, not for The Met. To settle on an architect for the Tang Wing, the museum adopted a workshop model, inviting a shortlist of relative newcomers to participate. Hernandez-Eli and others worked with the architects individually over the course of six months, meeting every two weeks, “getting to know them, guiding the process, helping them understand the constraints—just like the Hidden Room project.” In the end they chose Escobedo, stating in a press release that “her work draws from multiple cultural narratives, values, local resources, and addresses the urgent socioeconomic inequities and environmental crises that define our time.”

Alongside supporting newer architects, another opportunity for owners involves socioeconomic and environmental impact. For Hernandez-Eli, “design coordinates labor and materials around a set of values and manifests those values.” He continues, “engaging with architects who demonstrate a commitment to craft and artisanship, we’re looking to proactively curate the dollars [associated with our projects] into the local economy, local craftspeople, new technologies, so that we can participate in building a robust middle class.” This translates into job creation; for example, instead of importing artisans for a project, “we might fly them in to teach artisans here, who then develop new skillsets and become resilient themselves,” Hernandez-Eli explains. “It’s about keeping things hyperlocal, not shipping your granite in from Italy, but sourcing materials from within, say, a 50-mile radius,” thereby supporting regional suppliers and reducing the project’s carbon footprint. Hernandez-Eli’s larger message for owners? “Designers can’t maximize their impact alone. It is the responsibility of owners to set our designers up for success—embrace the work they’re doing and partner with them to choose how we spend those dollars.”

In a few months, Hernandez-Eli will help students explore the evolution of museum typology. Simultaneously, he will model non-conventional methods for championing architecture and architects. As Hernandez-Eli observes, “my story shows students that there are different paths to take, and there are different ways of advocating for architecture.”

Remembering Joseph Edward Brown (1947–2024)

Joseph Edward Brown (MLAUD ’72), whose unrelenting promotion of landscape architecture influenced several generations of practitioners, died on Thursday, October 31st, in San Francisco after an extended illness. I was fortunate to have witnessed the loving care his spouse, Jacinta McCann, gave him over the long years of his physical impairment—one of the truest measures of human devotion I have ever encountered.

In my lifetime, there was no stronger champion for the striving achievement of landscape architecture practices than Joe, a tireless man whose energy could not be dampened. The story of his advocacy for the field necessarily starts with the formation of EDAW in 1973, when Garrett Eckbo, Francis Dean, Don Austin, and Ed Williams reincorporated the small but powerfully innovative firm that Eckbo and Williams had originated two decades earlier. EDAW expanded steadily on a wave of emerging environmentalism, delivering new scales of environmental planning including the expansive California Urban Metropolitan Space Study of 1965 and a similar plan for the state of Hawaii in 1970. Joe joined EDAW in 1974 in California and, seeing the East Coast as an opportunity, soon opened the firm’s studio in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1976.

It was in the District of Columbia that Joe developed his full-throated voice for visibility, credibility, and influence for the discipline. Through sustained and strategic promotion, the Alexandria office became a powerhouse in Washington. EDAW’s Alexandria principals assiduously studied how design intersects with governance and public process—the only key to success for anyone working in the capital city. They conquered the art of persuading and winning with agencies including the National Capital Planning Commission, the US Commission of Fine Arts, and the National Park Service. The DC projects were significant, from the Monumental Core Master Plan, Constitution Gardens, the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial, and the National Museum of the American Indian, to perhaps the ultimate prize in planning the capital city: Joe’s leadership role in a mega-team for the all-important plan for the District and beyond, called Extending the Legacy, in 1997.

Meanwhile EDAW was expanding globally. In 1992, Joe took the reins of the firm as president; satellite offices thrived in Atlanta, Sydney, and London. By 1994, it was a 400-person entity banking on new global markets including Europe, China, and the Global South. By 2000, EDAW stood at 1,000 people. In 2005, EDAW joined the AECOM companies, one of the world’s largest infrastructure consulting firms. With this merger, EDAW’s landscape practice would gain hold on an unlimited market worldwide.

EDAW kept its identity within AECOM for nearly a decade, but in 2009, after its own legacy of 50 years of transformational practice, the firm was consolidated into AECOM. Many viewed this as a diminishment—it was sad to see the Eckbo Dean Austin & Williams legacy retired. But Joe saw his team of landscape architects working on the largest and most complex projects throughout the world. He led AECOM’s Planning, Design, and Development team, and became the Chief Innovation Officer, prior to his retirement in 2016. Joe had moved beyond visibility and credibility for the field; he was satisfied that landscape architects were leading and collaborating everywhere, and he continued to motivate everyone he knew. He was more than once heard saying, “Make big plans now . . . or be prepared to make little plans for a small future.”

An anecdote: In the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, Joe did some teaching at the GSD, mostly workshops in core studios and guest appearances in classes, and we spent a bit of time together, sharing studio reviews and occasional dinners. At the time, I taught the MLA II Proseminar, which aided first-semester students in the shaping of an academic platform for their two years in the program. I’d invited Joe to speak with the class about his career path and his views on practice. Joe headed to the blackboard after a short introduction. There he wrote “EDAW” and “Reed Hilderbrand” across the top. He said he wanted to talk about where this class of students wanted to work once they’d finished their MLA degrees. He explained that if you wanted to have impact, EDAW would take you places you’ve never imagined, where you can design anything. If you want to work in an atelier, then you should work for Gary’s firm; you will really learn how to design, but the impact will be smaller. A friendly hour-long debate ensued. His voice, forever a bit on the raspy side, was always intense, directive, and encouraging. Joe and I remained good friends. We both liked our respective corners of the world.

Whether he saw you as a boutique artist or a large firm collaborator, Joe always seemed to be as keen on your firm’s success as he was on his own, as a range of practitioners attest. Gerdo Aquino FASLA (MLA ’96) of SWA has noted that “Joe was an important mentor to me in my early professional years at EDAW and SWA. He was the one who talked me into attending graduate school—said I wouldn’t regret it. He was a north star for so many of us.” Cindy Sanders FASLA of OLIN said, “Joe was my most significant mentor in the business of the business. He taught me nearly everything I now know about the business of landscape architecture. I was a good student of his academy.” And James Burnett FASLA of OJB observed, “He wanted us all to make it and prosper because he understood how important it was for our firms and our profession to be strong.”

Joe received many accolades in his career, including the 2009 American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) Medal, the association’s top honor. That same year—the year of the full merger into AECOM—EDAW received the ASLA Firm of the Year award as well. The most significant recognition in my view, and I like to imagine possibly for him, was Joe being presented with the Landscape Architecture Foundation Medal in 2019. The ceremony in Washington, DC, was deeply affecting, a moment those in attendance will never forget. While Joe was by then barely able to speak, he was fully aware, with Jacinta at his side, that all in the room felt a great sweep of emotion and gratitude for his determined and tireless contributions to the advancement of landscape architecture.

Joe’s dedication to furthering the discipline of landscape architecture persists. Established in 2017 with Jacinta, the Joe Brown and Jacinta McCann Fund for Faculty Research provides support for both new and ongoing research projects conducted by junior faculty in the GSD’s Department of Landscape Architecture or Department of Urban Design, with a particular interest in interdisciplinary projects.

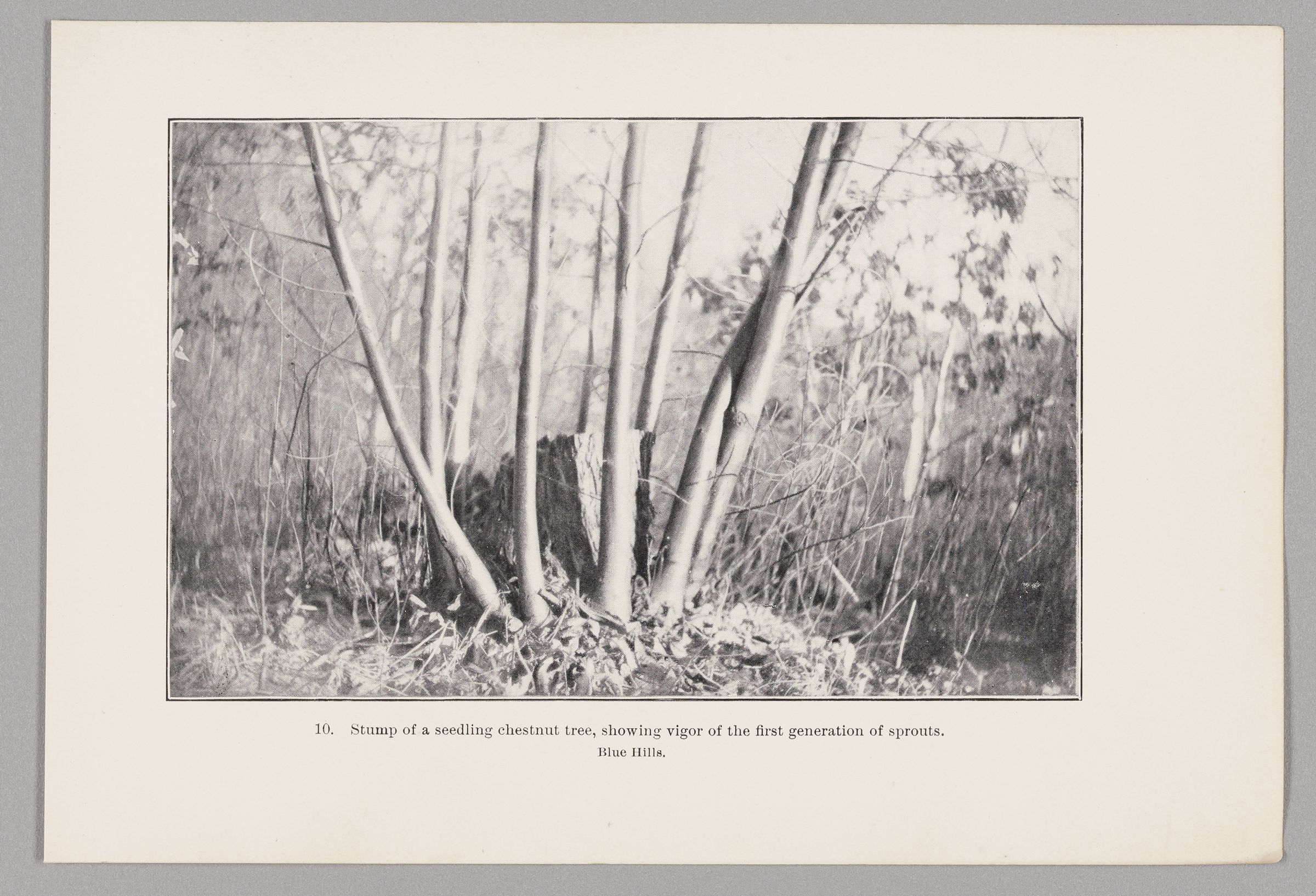

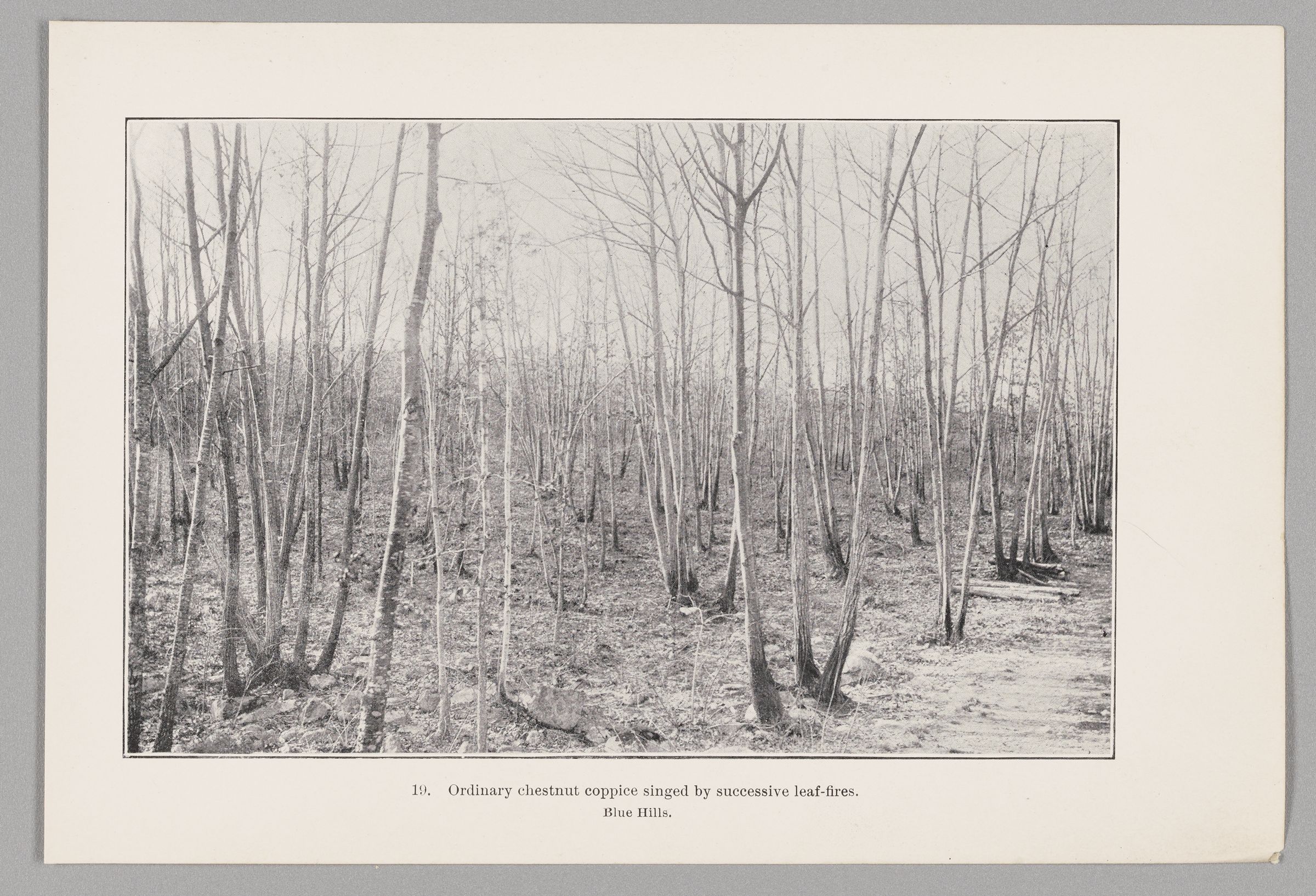

Forests Are Cultural Constructs

One hundred thirty years ago, environmentalist and landscape architect Charles Eliot walked the Blue Hills, a vast green swath south of Boston, envisioning its transformation into a wilderness reserve. Looking out to the horizon from the hill’s peak, he saw not a wild forest but hundreds of thousands of coppices— clusters of sprouting trunks created by cutting a tree close to the ground and causing it to release what Anita Berrizbeitia calls “repressed buds” that wait beneath the bark. Walking the same hills Eliot traversed all those years ago, and in the process of researching the wilderness’ origins in archives, Berrizbeitia was surprised to find that Eliot’s Blue Hills reservation plan emerged out of an agricultural forest that provided lumber for settlers for two hundred years, and that he proposed to remove more than 400,000 coppiced trees by using grazing sheep to prevent the sprouts from developing, and then lifting the roots systems out of the ground by hand, one by one—a laborious, time-consuming process.

Her research of the Blue Hills led Berrizbeitia, professor of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), to consider what makes a forest “wild,” how all forests are culturally constructed, and how our contemporary landscape honors or erases indigenous history. These are the themes that she’s now exploring with her students in “Forests: Histories and Future Narratives,” a course that follows on the heels of Forest Futures, the exhibition she curated at the GSD last spring.

In temperate forests, write Rob Jarman and Pieter D. Kofman in Coppice Forests in Europe, “simple coppicing” can be achieved in mid-winter, when the tree is dormant. Cut the tree near the base, and then, come spring, explains Berrizbeitia, “the energy previously spent on the canopy and the leaves but now entirely contained in the root system is reassigned to dormant buds contained in the remaining stump or in the roots.” The trunk sends up “vigorous growth of straight poles within a short span of time.” The new shoots can be cut at whatever size is required for the lumber’s purpose (firewood, construction, furniture, etc.), and can be harvested over and over again for decades—even centuries—from every three to 30 years. “In a coppice system, the roots remain alive and productive for hundreds of years,” says Berrizbeitia. “Historian Oliver Rackham refers to this phenomenon as the ‘Constant Spring.’” Coppiced trees in England have survived for two thousand years and hold in their trunks valuable information about the past. Kofman and Jarman note that coppices “of all kinds and ages are of interest for their associated wildlife and for their cultural heritage.” Some plant and animal species need the “open spaces…, edge habitats and alternate light and shade conditions” that coppices, as opposed to the thick overstories tall trees, provide.

In attempting to transform an agricultural forest into a recreational one, Charles Eliot confronted questions about what makes a forest and how cultures are reflected in those landscapes.

Thousands of years before colonists arrived in New England, the Massachusett nation inhabited the region we refer to as “The Blue Hills.” In fact, “Massachusett” means “people of the Great Hills.” For 8,000 years before European contact in the 1600s, the indigenous nation farmed corn, squash, and beans; used trees for their fuel, wetus, and canoes; and, says Berrizbeitia, “walked through the valleys on their way to the Neponset River, to fish and to transport material to the shore, or to return to their fields of corn in the meadows of Quincy, or to their village on the borders of Ponkapoag bog.” They had access to wild game for meat and furs, as well as valuable mines from which, for thousands of years, they drew granite and “rhyolite, a volcanic rock with high silica content” to “make sharp tools and spears.”

When European colonists arrived in 1620, like all tribes along the east coast, the Massachusett had just suffered through a plague, and, in the decades that followed, struggled to maintain their lands in the face of the thousands of Europeans who arrived on their shores. They were removed from the Blue Hills to Ponkapoag, where, today, they write, “we continue to survive as Massachusett people because we have retained the oral tradition of storytelling just as our ancestors did.”

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, settlers clear-cut the forests, taking first the white pines, whose strong trunks made excellent sailboat masts. They turned over thousands of New England acres of rocky soil, built stone walls to mark their property, and planted crops to feed the colonies— often with the forced labor of enslaved Africans and indigenous people whose land the colonists stole.

Berrizbeitia surmises that, in the late 1800s, Eliot knew about the Epping Forest in England, where pollarded trees (created in the same way as coppices, but cut higher up their trunks) had been harvested for centuries and inspired a debate among residents and experts: Should the coppiced trees remain or be removed? What should this new forest look like? Designer and social activist William Morris argued that the coppices represented an important part of the cultural history of the region, and vehemently opposed biologist Alfred Russell Wallace’s proposal to import trees from other nations (including the US and China) to help diversify the English forest. This first attempt to apply biogeographic diversity to design was rejected, and the pollarded trees remained. They can be found there today, in tall clusters, evidence of the forest’s history.

In the Blue Hills, says Berrizbeitia, Eliot noticed seedlings growing between the coppices. He knew that, if left to its own devices, the forest would regenerate. He was right—but, frequent forest fires prevented the natural regeneration of the forest.

The Massachusetts government decided they had to intervene. “They realized, ‘we devastated our soils with agriculture.’ What’s going to happen to us?” To jumpstart a new succession cycle, as the regeneration process is called, they planted white pines in large numbers, adding over one and a half million in the Blue Hills. This is a practice the US forest service continues today, planting pines and other trees throughout the US, an aspect of silviculture—a word coined in the late nineteenth century, when Eliot was hard at work on the park system.

All along the outskirts of Boston, the lands Eliot developed into the Metropolitan Park system were full of coppiced forests, the primary source of fuel in the area until the transition to coal took place in the 1880s. Instead of remnant wilderness, these were fallowlands, abandoned forests that needed to be put to a different use. He likely began his project to remove the coppiced trees, Berrizbeitia theorizes, but soon enough, the gypsy moth and chestnut blight took hold in the area, killing the coppiced trees. Thousands of new trees—a variety of species—were brought in from nearby nurseries, and when those failed, more were planted. Berrizbeitia is now researching the infrastructure that drove the transformation of the Blue Hills—including where those millions of pine seedlings were cultivated, and how they were transported and stored.

She argues that Eliot’s proposal to remove the coppiced trees was an attempt to erase the imprint of settler’s colonization of the Massachusett people’s land, and that although he knew the importance of the hills to the indigenous nation, he did nothing to recognize them beyond the naming of landmarks.

In the face of the current environmental crisis that requires a transition from fossil fuels to renewable and diverse energy sources, coppicing has reentered the conversation on sustainable resources. Combined with other energy sources, such as solar and wind power, says Berrizbeitia, it’s possible that harvesting lumber with coppicing techniques could become another energy resource. Although still widely used in Europe, coppicing is now experiencing a revival in the US. Berrizbeitia’s research on the Blue Hills restores to the region the story of a designed forest whose history might help us move into an uncertain future with more tools at hand.

The GSD Community Feels at Home in the Smithsonian Design Triennial

Challenging and wide-ranging conceptions of “home” underpin the design projects on view at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York. The seventh edition of the recurring survey of contemporary design practices, Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial features 25 site-specific projects, all new commissions, that reconceptualize “design’s role in shaping the physical and emotional realities” associated with home. Faculty, alumni, and affiliates of the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) are core participants in the exhibition, which investigates the historical power dynamics and contemporary political economies that structure domestic space. Michelle Joan Wilkinson , a 2020 Loeb Fellow and curator of architecture and design at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, DC, organized the exhibition with a team led by co-curators Alexandra Cunningham Cameron and Christina L. De León. Isabel Strauss, a 2021 MArch I graduate and curatorial assistant at NMAAHC, also worked as a curatorial assistant on Making Home.

The theme of the triennial was especially apt given its setting. The Cooper Hewitt occupies the former residence of Gilded Age steel magnate Andrew Carnegie. The grandiose turn-of-the-century mansion on Manhattan’s Upper East Side often serves as a foil for triennial projects that propose more democratic ideals of domesticity. This rethinking begins with the exhibition design by Johnston Marklee, the firm led by GSD design critics in architecture Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee. Tasked with negotiating the public mission of a Smithsonian institution, the historic private home that serves as the setting, and the domestic themes of the triennial, Johnston Marklee’s interventions aim to “dismantle the social and spatial hierarchies built into the mansion’s architecture,” according to a gallery text. Accessible, cushioned seating creates inviting spaces amid the imposing halls. Expansive area rugs with bold geometric patterns recalling linoleum floors playfully exaggerate the scale of the interior spaces, while wood veneer exhibition furniture, evoking everyday cabinetry, contrasts with the mansion’s ornate carved-wood details.

The installation “Ebb + Flow” by Artists in Residence in Everglades (AIRIE) , part of the exhibition’s first section, “Going Home,” feels subtly integrated into the mansion’s glass-enclosed conservatory even as it foregrounds historically marginalized perspectives. Germane Barnes, winner of the 2021 Wheelwright Prize and an alumnus of the AIRIE program, designed listening stations with headphones that visitors can use to hear a soundscape that includes recordings of Everglades preservation advocates Daniel Tommie (Seminole Tribe of Florida), Dinizulu Gene Tinnie, and Dr. Wallis Tinnie. Now threatened by development, the Everglades are a unique ecological system and the site of Indigenous cultural traditions, scenes of which adorn cushions that line the room. The sculptural objects Barnes created for the listening stations are “inspired by the Freedman lineage of movement and resourcefulness,” a reference to the African American communities that found freedom from slavery in the Everglades and other marshy locations beyond the reach of plantation owners.

The AIRIE project was one of several in the exhibition that feature Indigenous perspectives on home environments. In the exhibition’s first gallery, a display of vibrant turkey-feather capes, by the Lenape Center with Joe Baker, serves as an opening acknowledgement of the Lenape people as stewards of the land on which the museum sits. On the museum’s top floor, in the exhibition’s “Making Home” section, Indigenous building practices from the Hawaiian Islands inform “Hālau Kūkulu Hawaiʻi: A Home That Builds Multitudes,” a project by After Oceanic Built Environments Lab , led by 2015 MDes graduate Sean Connelly, in collaboration with Leong Leong Architecture. The designers employ the lashing techniques of canoe construction (wa‘a) to create the structure of a large hale, or traditional building. An accompanying video details how the structure and building techniques are grounded in the Native Hawaiian concept of ʻāina, or land “that which feeds.”

In a nearby gallery, “We:sic ’em ki: (Everybody’s Home)” by Terrol Dew Johnson and ArandaLasch, to which GSD 2010 MArch alum Joaquin Bonifaz contributed, demonstrated how traditional building, craft, and culinary techniques of the American Southwest informed the design of a home for the Tohono O’odham Nation.

Several of the participants in Making Home also contributed to the GSD’s 2023 Black in Design Conference , “The Black Home,” an event that anticipated some of the triennial’s themes. For example, Barnes participated in the keynote panel discussion while Curry J. Hackett, a 2024 MAUD graduate, led a workshop on “Archiving the Black Home.” At the Cooper Hewitt, Hackett and Wayside Studio present “So That You All Won’t Forget: Speculations on a Black Home in Rural Virginia,” part of the triennial’s “Seeking Home” section that includes projects offering utopian gestures and imaginative perspectives. Hackett’s project becomes apparent first through its aroma: he has lined a gallery with curing tobacco leaves. Amid the bunches of tobacco are “speculative objects,” including an decorated church fan and a painting by his mother. The project is a meditation on tobacco farming in Hackett’s family history –“an unlikely celebration of an otherwise haunting crop”—and the designer’s personal “speculation on what life on the land was like or could be.”

This kind of speculation can drive tangible proposals on how the basic concept of home can serve to address social inequality. Led by 2013 Loeb fellow Deanna Van Buren , Designing Justice + Designing Space produced “The Architecture of Re-entry” an installation that includes tidy enclosures, each featuring a Murphy bed, workspace, exercise equipment, and a small library. The cubicle-like interiors could be full-scale mock-ups of dorm rooms, but Van Buren’s project aims to offer a sense of stability to those who need it most, focusing on transitional housing for formerly incarcerated people. The semi-private living spaces are envisioned as elements within larger open structures that include space for supportive programs and shared facilities. The proposition is that a well-designed space, however modest, can have life-changing effects as a source of attachment and dignity.

The notion of “home” that emerges from the triennial is an unsettled, contested category. Within the museum’s purview of “the United States, US Territories, and Tribal Nations,” vastly different meanings of domesticity coexist. A source of strength, identity, and comfort, home can also represent profound loss and estrangement. In surveying contemporary designers who grapple with the dynamics of private space, Making Home effectively prompts a public discourse about what might be shared in collective visions for home while also making visible the real divisions still to be addressed.

The Renovated Gund Hall: A Paradigm for the Revitalization of Mid-Twentieth-Century Architecture

Harvard Graduate School of Design students returned for the fall 2024 semester to find Gund Hall transformed. Yet the iconic building looked much the same as it had since opening a half century ago. And this was indeed the point. Over the summer, a meticulously planned renovation enhanced the facility’s energy performance, sustainability, and accessibility while conserving its original design. Led by Bruner/Cott Architects, this project has transformed Gund Hall into a paradigm for the rehabilitation and stewardship of mid-twentieth-century architecture.

Designed by Australian architect John Andrews (MArch ’58), Gund Hall opened in 1972 to house Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD). Since this time, the building’s glass-enclosed five-story studio block, known as the trays, has served as the GSD’s physical and metaphorical center—where students work, interact, and exchange ideas. The trays have been quite successful as a workspace and social condenser, as Andrews envisioned, but less so in terms of environmental consciousness and user comfort. Single-pane glazing and minimally insulated exposed concrete, commonplace at the time of construction and used by Andrews in a forward-thinking fashion, ultimately made the building difficult to heat and cool. Studies preceding the renovation revealed that the trays, which account for 28 percent of Gund Hall’s floor area, were responsible for 46 percent of the building’s energy consumption.

Alongside these financial and environmental costs came a very human one: within the trays, students experienced thermal conditions that ranged from sweltering heat to hand-numbing cold, all while grappling with glare from direct and reflected sunlight and leaks from the stepped roof. Andrews’s experimental design gave rise to an impressive building marked by vulnerabilities that future generations, with access to advanced technologies, needed to address.

David Fixler, lecturer in architecture at the GSD, is chair of the Building Committee, which consists of faculty representing the school’s three core disciplines and oversees the renovation project. According to Fixler, the idea to upgrade the trays’ glazing “had been in and out of the GSD’s eye for the better part of two decades.” The past five years saw the envelope project “revived with a strong emphasis on comfort, energy efficiency, and larger sustainability goals to prove that a building like Gund Hall,” which predates contemporary energy-conservation concerns, “can be made a more environmentally friendly place.” This was a complicated proposition, however, as the renovation’s mandate was to improve Gund Hall’s energy efficiency while acknowledging the stewardship value in conserving Andrews’s original design. In addition, as Fixler noted, “Harvard is a place known for innovation and great design, and we wanted to reflect that as well.”

To develop a realistic scope for the summer renovation—itself the first phase of a multi-year renovation project—the Building Committee worked closely with Boston-based Bruner/Cott Architects, specialists in historic preservation. Project architect George Gard, associate at Bruner/Cott and GSD alumnus (MAUD ’14), noted that the design team’s focus rested on “two main pillars: conserving Gund Hall, and making its facade world-leading in performance.” Harnessing the technology to create a first-rate facade, Gard clarified, was “the easy part; the hard part was understanding the building’s conservation value and marrying the technology to it” while meeting strict dimensional parameters for the glazing members. Jason Jewhurst, Bruner/Cott principal-in-charge, offered an illustrative example, citing the design team’s decision to keep the 50-year-old facade support steel within the studio’s original glazing system. This move aligned with the building’s preservation and helped minimize carbon emissions, yet it also underscored a challenge applicable to much of the Gund Hall renovation: “how do we work with the existing fabric and elevate it with new technology?” Jewhurst asked. As Fixler observed, in the planning and design stages as well as in the field, “this project involved a lot of artistry.”

A primary achievement of the ambitious renovation, which followed a tight construction schedule initiated after commencement in May, involves the replacement of the glass encasing the trays. In total, this amounts to 1,617 glazing units equaling a glazed area of 15,475 square feet. The east curtain wall and clerestory windows employ triple-pane glass, while a custom hybrid vacuum-insulated glass (VIG) composite contributes an additional layer of insulation to the north and south curtain walls. By leveraging the insulating properties of the internal vacuum and marrying it to an additional layer of conventional insulating glass in a sandwich that is overall only a few millimeters thicker than conventional double glazing, the hybrid VIG offers unprecedented thermal resistance. These hybrid units can deliver energy performance that is two to four times better than standard insulating glass and up to ten times more efficient than single-pane glass. While this technology has developed a strong track record in Europe, the Gund Hall renovation is among the first projects in the United States to employ hybrid VIG on a grand scale.