Bernhard von Oppersdorff (MDes ’22) wins Pension Real Estate Association scholarship

Bernhard von Oppersdorff (MDes ’22)

Excerpt: Creating Universal Goals for Universal Growth, by Betsy Hodges

“Five years ago, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Just City Lab published The Just City Essays: 26 Visions of Inclusion, Equity and Opportunity. The questions it posed were deceptively simple: What would a just city look like? And what could be the strategies to get there? These questions were posed to mayors, architects, artists, philanthropists, educators and journalists in 22 cities, who told stories of global injustice and their dreams for reparative and restorative justice in the city. These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays

These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays

Creating Universal Goals for Universal Growth

By Betsy Hodges

There is a difference between equality and equity. Equality says that everybody can participate in our success and equity says we need to make sure that everybody actually does participate in our success and in our growth. A just city is a city free from both inequity and inequality.

We pay a significant price for inequities—in the billions in our cities, in the trillions nationwide. Growth is commonly pointed to as a solution, but growth for the sake of growth alone cannot solve these inequalities and inequities. However, solving these inequalities and inequities gets us growth.

Inequities make our cities risky business ventures. We don’t have the workforce that we need because we are not getting everyone into the workforce; we don’t have the consumer base that we need because not everyone can afford to consume. It creates an atmosphere where people are hesitant to invest because they don’t know if they’re going to have the consumer base or the workforce base that they need.

My city of Minneapolis suffers from some of the largest racial disparities in America on almost any measure: employment, housing, health, education, incarceration—the list goes on. For example, while 67 percent of white kids graduate on time from Minneapolis Public Schools, only 37 percent of African-American and Latino kids do, and just 22 percent of American-Indian kids. When you consider that in just a few years, a majority of Minneapolis’ population will be people of color, this disparity is economically unsustainable, in addition to being morally wrong.

Minneapolis is in the midst of a building boom; cranes dot the sky as far as the eye can see. But growth alone can’t solve our equity problem. It’s not turning Minneapolis into a just city, because our current growth doesn’t include everybody. Even though our overall unemployment rate has declined, the gap between white people and people of color remains the same.

The moral of this story is that if your boat is leaky or you don’t have one to begin with, the rising tide can’t and won’t lift you.

In our just city we must accept that inclusive growth is a better strategy than growth alone. Inclusive growth means that your life outcome is not determined by your race, age, gender, or zip code. Inclusive growth means we aren’t leaving any genius on the table. To achieve this, we need two things: universal shared goals about what we want for ourselves as a people and as a community, and the policies that will ensure that people get there. Continue reading on designforthejustcity.org…

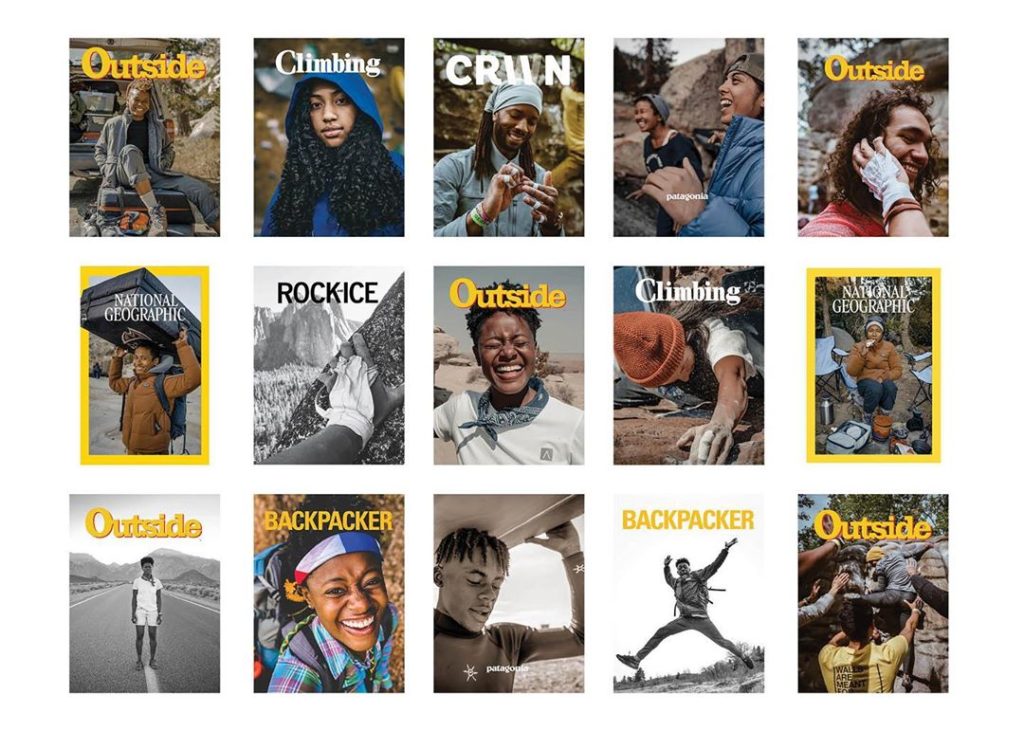

L. Blount (MLA ’17) is changing how we envision the natural landscape—and how people of color are depicted within it

Although she graduated from the Harvard Graduate School of Design Master in Landscape Architecture program in 2017, Lanisha “L.” Blount would be hard-pressed to call herself a designer—the term “designer” feels too limiting to describe the range of her professional interests and activities. When she’s not hanging onto the edge of a boulder by her fingertips, or composing photo essays of her friends on their climbing adventures all over California with brands like The North Face and Arc’teryx, she’s working as an innovation consultant, partnering with Fortune 100 companies to help shape the future of their industries. “My path from the GSD has been very non-traditional,” Blount acknowledges. “But who says you have to be a traditionalist to change things? There’s more than one way to effect change in the environment, and I wanted to think much bigger.” Lately, Blount has trained her focus on changing how we envision the natural landscape—and specifically, how people of color are depicted within it. As outrage over George Floyd’s killing sparked conversations about systemic racism across the country, and the coronavirus pandemic precipitated a spike in traffic to national parks, Blount was compelled to bring the outdoor and adventure industry into the dialogue. “I looked up these [adventure] magazines to see the last time they had a person of color on the cover and it was often not even in the last two years,” she says.In response, she designed and posted to Instagram a series of speculative covers for major outdoor publications, each featuring her powerful portraits of climbers of color of all genders. With these visual provocations learned from consulting, Blount asked fellow adventurers to “imagine if [they] didn’t have to imagine.” Blount’s project also explicitly called upon leading outdoor brands to step up their efforts to build a more diverse and inclusive industry. “June was such a harrowing month,” Blount recalls. “Doing this storytelling was all about illuminating joy outside and rethinking how I can keep elevating people who should be on covers.”

Covers from Blount’s viral social media series. Image courtesy of her Instagram (@urbanclimbr).

Blount (MLA ’17) during her time as a student at the GSD. Image courtesy of her Instagram (@urbanclimbr).

Cooking Sections’ Salmon: A Red Herring: Are our ideas about color and nature based on fundamental misconceptions?

How do you like your salmon? If you prefer the natural look, that’s fine—there’s a choice of 15 official shades available. This is not a joke. According to Cooking Sections’ new book, Salmon: A Red Herring, our commonly held ideas about color and nature are based on some fundamental misconceptions and misperceptions. Cooking Sections is the name of a duo of spatial practitioners consisting of Daniel Fernández Pascual (the 2020 recipient of the Harvard GSD Wheelwright Prize for his research project Being Shellfish: The Architecture of Intertidal Cohabitation) and Alon Schwabe. Adopting a multimedia, multi-discipline approach including installation, performance, mapping, and video, the London-based group explores “systems that organize the world through food” within the overlapping boundaries of architecture, visual culture, and ecology.

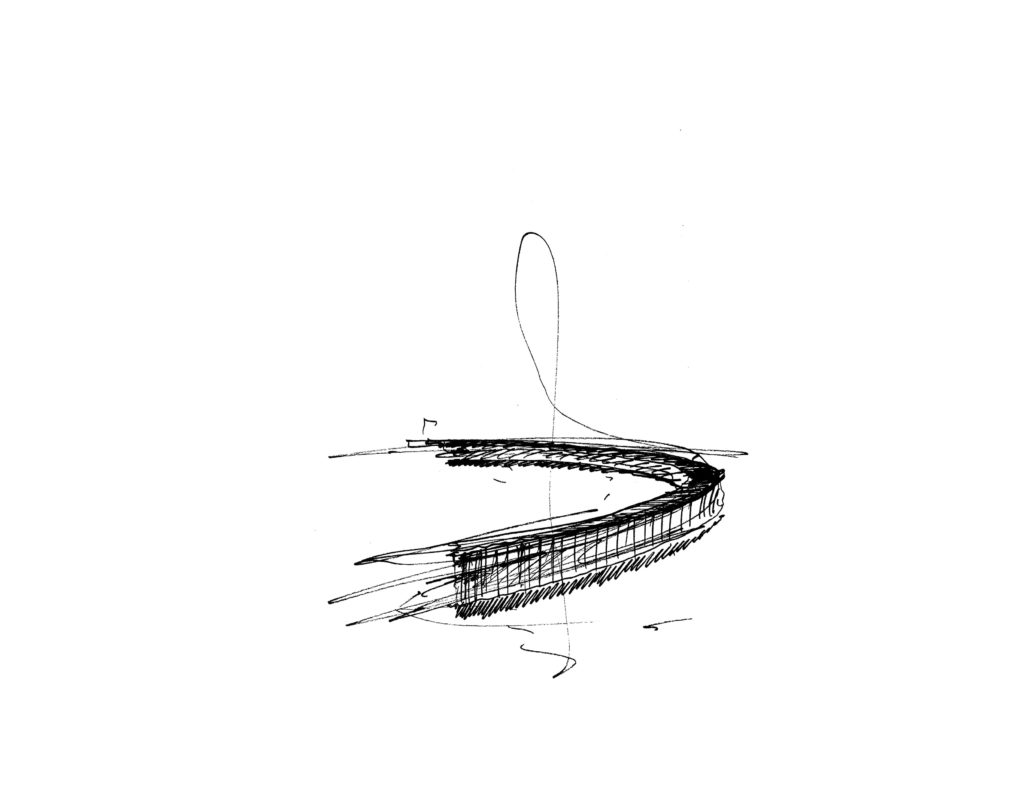

Fernández Pascual’s winning Wheelwright Prize proposal will examine the architectural potential of the intertidal zone (“coastal territory that is exposed to air at low tide, and covered with seawater at high tide”), and specifically how seaweed and waste shellfish shells can be used to create a new type of concrete—an ecologically friendly solution to one of the building industry’s biggest contributors to climate change.

Oranges Are Orange, Salmon Are Salmon

By Cooking Sections

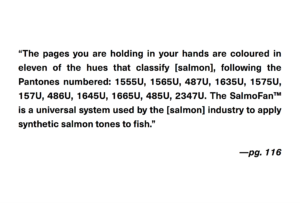

Oranges require orange to be. They are a color expectation. If an orange is not orange, it is no orange. Oranges originated in China, where they were crossbred from a mandarin and a pomelo as early as 314 B.C. From there, oranges passed from Sanskrit नारङ्ग (nāran˙ga) through Persian نارنگ (nārang) and its Arabic derivative نارنج (nāranj). Traveling to continental Europe with the Moors, naranjas soon dotted al-Andalus and Sicily. Oranges arrived in England from France in the fourteenth century, their bright skins holding a taste of a color that became popular in markets, on palates, and, eventually, in tongue. For centuries, oranges were orange and, still, orange was not a color—it was called yellow-red. It took another two hundred years for the color to earn its name, to become a form that could give itself to others—to be ascribed to flowers, stones, minerals, and the setting sun. To the west, oranges followed the path of Spanish missionaries and lent their name to Orange County and the Orange State. In California, the fruit fed the miners of the gold rush who passed through mission towns. In Florida, there were so many groves that, by 1893, the state was producing five million boxes of fruit each year. In this tropical climate—nights too humid and too hot—oranges would ripen too quickly: they were ready to be eaten while still green. And so, from the twentieth century onward, green oranges have been synthetically dyed orange, coated to match consumer expectations. Orange reveals that humans cannot imagine a species detached from its color, even when we are the ones who detach it. Amid all the observations that are made about industrialization and its consequences, the following is rarely heard: the world’s colors are shifting. From infancy, we describe, dream, and remember predominantly with our sense of sight, and there is no seeing without exploring, no static vision. We are raised to bend color to our will, at times admonishing it and elsewhere applying it to our liking. We grow up coloring in pictures of the world—trees are green, earth brown, and yolks yellow. That everything else in life is turned regularly upside down is only tolerable because oranges remain orange and the sky blue. An increasing amount of industrial energy is directed, therefore, toward dyeing the world in natural colors so that life and commerce may proceed. But dyes may miss their mark. Shifting cues in flesh, scales, skin, leaves, wings, and feathers are clues to the environmental and metabolic metamorphoses around and inside us. The force that is color is not for domestication; it is fugitive. Color colors outside our lines. * In 2018, an eye-catching sparrow was spotted on the Isle of Skye. The sparrow was bright pink. We know what sparrows are supposed to look like, because they have evolved with us. Over several millennia, food scraps from human settlements attracted sparrows from the “wild,” which caused them to mutate into a new species. “House” sparrows have since become a familiar sight wherever humans dwell, metabolizing the shades of our settlements into their brown-gray feathers. They are drabber than their older, tree sparrow cousins, who preserve the brighter tones of the forest. The pink sparrow, neither forest nor house, was a color leak. The sparrow had turned [salmon]. On the Isle of Skye—whose name comes from the Gaelic for “winged”—colorful feathers lure eyes. Anglers, fishing for sport, carefully tie fish flies from synthetic rainbow plumage that resembles insects, enticing salmon. These iridescent wings are easy prey. Salmon bite on the colors that they find attractive, only to swallow a deadly hook. In the nineteenth century, colonists in the tropics were drawn to exotic birds and sent them back to Britain. These startling hues and patterns inspired new recipes for salmon flies, and plucked feathers, far from their origins, were used to pluck salmon from their natal streams. A combination of toucans, peacocks, and macaws, the flies mimicked salmons’ cravings. Hued plumage was used to deceive: to confuse the edible and the deadly. Salmon, beings for whom the ingestion of color is essential, took the bait.

Cooking Sections, Salmon: A Red Herring (isolarii, 2020)

Sacred Groves and Secret Parks: A two-day colloquium focused on the landscapes of Orisha

Princess Faniyi in front of Gund Hall, Harvard Graduate School of Design. Photo: Moisés Lino e Silva

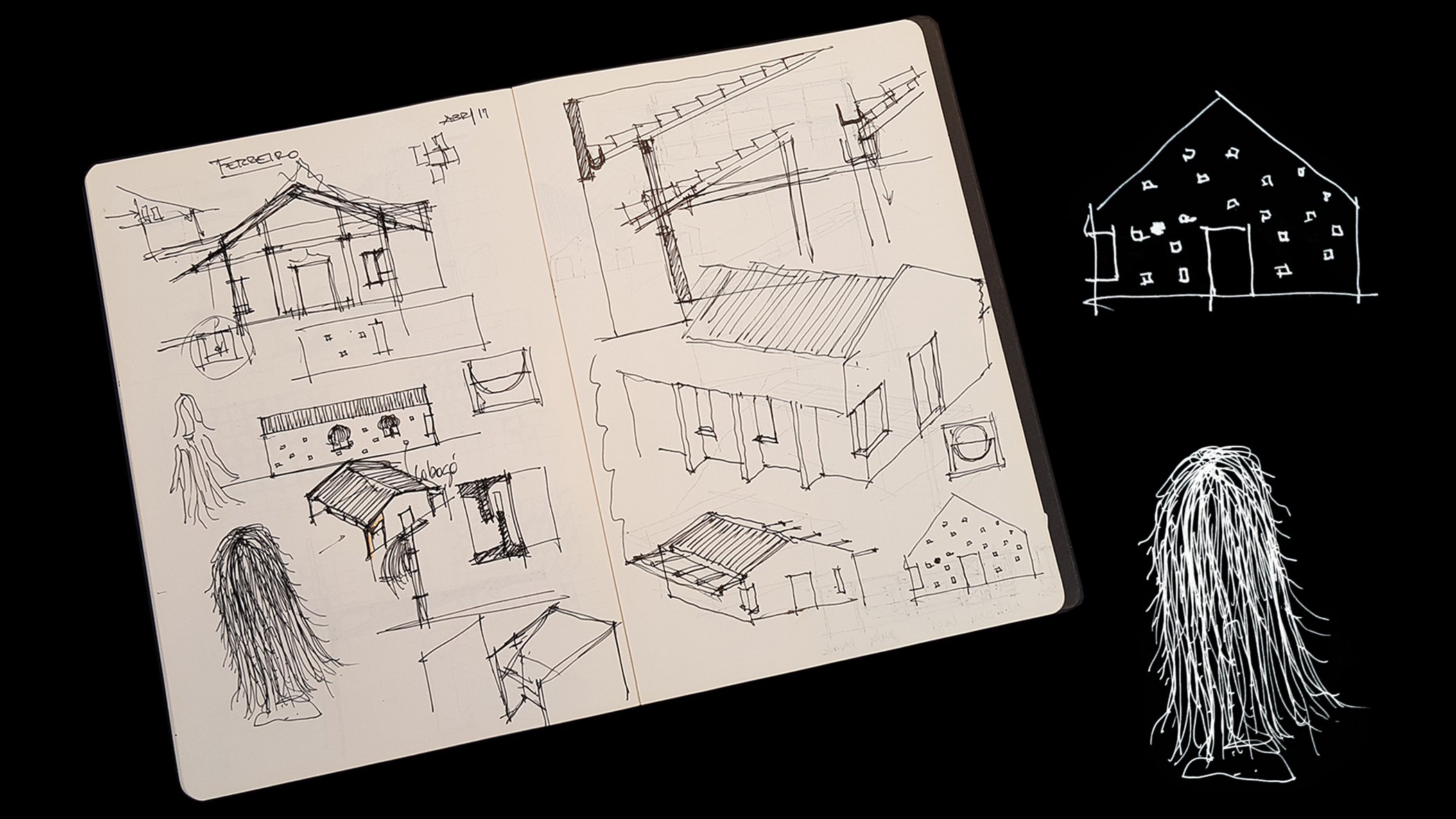

Form and ritual documented though architect’s sketches at Terreiro Tingongo Muendê. Credit: Sotero Arquitetos / Adriano Mascarenhas

Symbolic sculptures within the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove, Osogbo, Nigeria. Photo: Adolphus Opara

Sacred Groves and Secret Parks: An interview with Princess Adedoyin Talabi Faniyi and Moises Lino e Silva

The Graduate School of Design’s colloquium “Sacred Groves and Secret Parks” brought together scholars, architects, and practitioners to discuss the materiality and spatiality of Afro-religious diasporic practices, decentering Western canons of knowledge and new design possibilities for Brazilian and West African cities. Two of the key participants were Princess Adedoyin Talabi Faniyi and Moises Lino e Silva. Princess Faniyi is a Yoruba high priestess and the principal caretaker of The Adunni Olorisha Trust at the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove in Nigeria. The grove is famous for its incredibly lush lands and grand, artistic shrines, restored by Susanne Wenger and declared one of the two World Heritage sites in Nigeria by UNESCO in 2005. Lino e Silva is assistant professor of anthropological theory at the Federal University of Bahia and is an initiate of Candomblé (an Afro-Brazilian spiritual tradition) in Brazil. He met Princess Faniyi when he was initiated in the Yoruba tradition in Nigeria. Their research and partnership helped inspire the colloquium with the goal of expanding the international conversation to include an African spiritual perspective and informing future architectural practices. I spoke with Princess Faniyi, Lino e Silva, and Gareth Doherty, associate professor of landscape architecture at the GSD, about the cross over in their work and the themes of sacred spaces and architecture that were explored during the colloquium. Princess Faniyi, your talk was “The Politics of Orishas: How Osun Saved the Grove,” referring to the goddess Osun, to whom the Osogbo Shrine is dedicated. How did the colloquium expand knowledge and conversation around African spiritual traditions in terms of designing and building in landscapes? Princess Adedoyin Talabi Faniyi: The story of how the Osogbo sacred grove was made is that Osun told the people how to build on—and with—the land. The grove has preserved that land in a way that you do not often see. If there is more awareness in the preservation of the landscape of sacred groves, people can know the value of the land. And people will make the effort not to destroy the landscape that has been here for a long, long time—before the existence of any community. The spirit and the connection to the land is vital to the life of humanity. Gareth Doherty: The conference was very much based on landscape architecture. For example, we looked at the redesigning of Brazilian terreiros [shrines/ritual spaces] from three different architectural perspectives. On one panel, a Brazilian architect—Vilma Patricia Santana Silva from the Federal University of Bahia—was an initiate of Candomblé. In the process of doing her master’s thesis, through each of the design stages, she would consult with the Orisha. In a sense, she was listening to the landscape. You could take that perspective a step further and say she’s listening to the spirit of the land through the Orisha. That challenges our preconceptions of how designers and architects go about designing. In Nigeria, sacred groves have decreased in number, yet in Brazil, terreiros continue to multiply. What was the discussion surrounding sacred parks? Moises Lino e Silva: Terreiros are growing in number. Some of them are very small, but officially there are eleven hundred—and unofficially there may be 2,000 in cities. It’s not just about a collection of buildings; it’s also the spaces in between the buildings that are public space. Sacred parks are within the infrastructure and the greener areas of their urban forests. What came up in the conference was the concern regarding not just the internal aspects of the terreiros but their relationship to the outside and to the public domain. Princess Adedoyin Talabi Faniyi: The conference was crucial in raising awareness of the importance of the African spirit and Orisha tradition and the future of sacred spaces in these communities. With this partnership with Brazil and Nigeria, we are putting together a team so everyone can work together to preserve the landscape of sacred groves. What was the conversation around environmental perspectives and the need to recover natural landscapes and preserve existing ones? Princess Adedoyin Talabi Faniyi: There are major challenges in some places. UNESCO is there to protect the people and the places they are trying restore or preserve for sacred groves. My hope is that this conference will bring awareness and positive action with more ideas of how to protect and preserve the landscape. Moises Lino e Silva: In Brazil, our organizations collectively advocate for the city and its ecological value. Part of our agenda is considering the preservation of those spaces within the cities, which are getting increasingly dense. Nature within the city and landscape is at the root of the spiritual traditions. I think that’s an important dimension to conserve. Princess Adedoyin Talabi Faniyi: Sacred groves can be seen as a model for building in natural landscapes. So the example is the sacred groves and the connection to the Orisha and spirit of the land—but it needs to be a larger conversation. Every culture finds its own meaning and purpose in the land; and that also informs—and decides—the future of the landscape.Excerpt: Turning to the Flip Side, by Maruxa Cardama

“Five years ago, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Just City Lab published The Just City Essays: 26 Visions of Inclusion, Equity and Opportunity. The questions it posed were deceptively simple: What would a just city look like? And what could be the strategies to get there? These questions were posed to mayors, architects, artists, philanthropists, educators and journalists in 22 cities, who told stories of global injustice and their dreams for reparative and restorative justice in the city.

These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at designforthejustcity.org . We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab , and editor of The Just City Essays

Turning to the Flip Side

By Maruxa Cardama

On the flipside you can do anything (…) the flipside bring a second wind to change your world. Encrypted recipes to reconfigure easily the mess we made on world, side B

– Song Flipside, written by Nitin Sawhney and S. Duncan

My brainstorming for this essay started me thinking about the comprehensive list that follows the affirmation of “a just city is a city that…” But my brain fell to the temptation of looking at the task from the reverse angle. What are the key ingredients of the perfect recipe for the mess of injustice in a city? For me, in a nutshell, the key ingredients for injustice are poor, inadequate, or opaque or simply noninexistent frameworks, spatial planning, management, financing and governance. All these inefficiencies put together, we get a city that is trapped in, or inexorably marching towards, injustice.

The main point I would like to make is that frameworks, spatial planning, management financing and governance are essential foundations and enablers for a multidimensional conception of justice in a city. Why? Because justice in a city is about social, political, economic and environmental justice. Once more, why these enablers? Because not only they can, but actually in many cases will, deliver better results if conceived and operationalized with the city-region scale as their wider framework. Justice in a city goes beyond its administrative boundaries. Ultimately a city will not be just if it is triggering injustice in the peri-urban or metropolitan areas or the wider region it relates to.

Frameworks, Spatial Planning and Management

Today cities are home to half of the world’s population and three quarters of its economic output, and these figures will rise dramatically over the next couple of decades. Urban development, with its power to trigger transformative change, can and must be at the front line of human development.

We seem to forget, though, that urban development is a complex process. It is a social process, and one that develops over time. To avoid getting trapped in morally abhorrent injustice, it is about time we collectively realize that urban development, like any other complex social process, needs to be soundly and sufficiently framed, planned and managed. City and regional spatial planning—territorial planning—can be an essential enabler of justice. Continue reading on designforthejustcity.org …

Just City Lab collaborates with Mayors’ Institute on City Design to introduce inaugural MICD Just City Mayoral Fellowship

Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Just City Lab announces, in collaboration with the Mayors’ Institute on City Design (MICD ), the inaugural MICD Just City Mayoral Fellowship, which kicked off in late September 2020 and continues virtually through December 2020. The Fellowship convenes seven city mayors from around the United States to directly tackle racial injustices in each of their cities through planning and design interventions.

Especially as COVID-19 disproportionately harms the health and economic well-being of Black residents, and as national protests around policing and public safety affecting African-Americans continue, the MICD Just City Mayoral Fellowship focuses on planning and design solutions for the neighborhoods where these injustices play out. During the program, each mayor selects a predominantly Black neighborhood in their respective city that has historically experienced under-investment, and receives feedback on applying the language and tactics of racial justice to the neighborhood’s future.

Relatedly, the MICD Just City Mayoral Fellowship will utilize the Just City Lab’s Just City Index and lessons from the Lab’s 2019 convening, the Just City Assembly, which challenged design practitioners to create a more visible agenda for disrupting injustice through design. These resources will frame dynamic presentations and dialogues by and with experts in the fields of architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning, art activism, housing and public policy. Mayors will learn best practices from the nation’s leading experts on the intersection of urban design, planning, and racial justice while working toward creating a manifesto of action for the neighborhood they selected.

“This collaboration between the Just City Lab and the Mayors’ Institute on City Design could not be more timely, nor more important,” said Sarah M. Whiting, Dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design. “We all know that our cities need help in recognizing the forces behind racial injustices—particularly in predominantly Black neighborhoods—and in finding vocabularies and strategies for transforming them into places of equity and opportunity. I’m excited to see the impact that this program will have and hope only that it’s the beginning of a broader network of collaborations that will make ‘just cities’ the standard for what we expect, not the exception to what so many experience.”

The GSD’s Just City Lab is led by architect and urban planner Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning and founder of Urban Planning and Design for the American City.

The inaugural cohort of MICD Just City Mayoral Fellows is:

Mayor Stephen K. Benjamin (Columbia, South Carolina); Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba (Jackson, Mississippi); Mayor Shawyn Patterson-Howard (Mount Vernon, New York); Mayor Errick D. Simmons (Greenville, Mississippi); Mayor Yvonne Spicer (Framingham, Massachusetts); Mayor Vince R. Williams (Union City, Georgia); and Mayor Randall L. Woodfin (Birmingham, Alabama).

“Mayors are on the front lines of every difficult conversation our communities are having right now,” says Tom Cochran, CEO and Executive Director of the United States Conference of Mayors. “They have the power to seize this moment of reckoning with racial injustices and unite their communities around real solutions. The traditional MICD experience, with its candid, small-group format and access to national design experts, is so often transformative for mayors. There is no better model for empowering mayors to find solutions in our nation’s cities, and we are proud to partner with the Just City Lab to launch this new program.”

“This program will take the transformative power of MICD, which illuminates the power of design to tackle complex problems, and apply it to the defining challenge of our time: ensuring equity and justice for everyone regardless of their race or zip code,” said Jennifer Hughes, Director of Design and Creative Placemaking at the National Endowment for the Arts. “Building on the Arts Endowment’s vision to heal, unite, and lift up communities with compassion and creativity, we look forward to this collaboration between MICD and the Just City Lab.”

The Mayors’ Institute on City Design (MICD), the nation’s preeminent forum for mayors to address city design and development issues, is a leadership initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with the United States Conference of Mayors. Since 1986, MICD has helped transform communities through design by preparing mayors to be the chief urban designers of their cities. The Just City Lab is a GSD-based design lab led by Griffin. The Lab has developed nearly 10 years of publications, case studies, convening tools and exhibitions that examine how design and planning can have a positive impact of addressing the long-standing conditions of social and spatial injustice in cities.

From Times Square to the Grand Central, Jerold S. Kayden leads New York Times architecture critic on a virtual walking tour of Midtown

Jerold S. Kayden, Frank Backus Williams Professor of Urban Planning and Design, recently led architecture critic Michael Kimmelman on a virtual tour of Midtown Manhattan for the New York Times. The conversation is part of an ongoing series featuring virtual walks around New York City. Kayden, who received degrees in law and city and regional planning from Harvard, focused his tour on the legal history behind 42nd Street.

Experience the tour in the article “Times Square, Grand Central and the Laws That Build the City ,” in the New York Times.

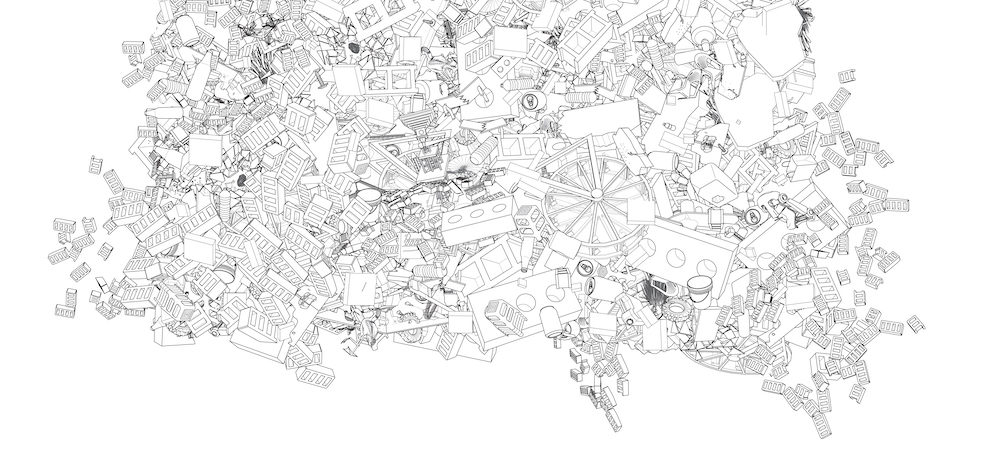

The Architecture of Waste

A linear economy conceives of waste as an end. It presumes that refuse cast off, flushed, or buried terminates the processes of consumption. The world’s dominant understanding of capital depends on this view, an idea that begins with resource extraction and leads eventually to disposal—what Annie Leonard, executive director of Greenpeace, refers to as “Take, Make, Waste.” Conceptually, “waste” represents a fundamental redesignation of value by separating out material that no longer seems to have potential. This conversion of material to waste results in the burial of more than 200 million of tons of detritus each year in the US.

An additional 100 million tons or so of disposed material feeds back into the consumption stream, but this happens almost invisibly. Sorted and repurposed for recycling and composting, divided waste streams merely hint at an inflection from “Take, Make, Waste” thinking. As far as most people can tell, different waste bins direct material to different trucks, which carry it to different ends. Even with effective recycling, it is difficult for people to conceive of the consumption process as other than linear, because used material still goes “away.” And virtually everything we use seems to start out as new. Even things made from reconstituted material, such as recycled or partially recycled paper, plastic, and metal, are essentially indistinguishable from the same items made from new materials. Compost is not much different: for most consumers it comes as soil, freshly packaged in branded, brightly printed plastic bags. So, crucial as it is, an effective recycling system disguises itself, for consumers, as waste disposal.

Huge changes in the linear consumption stream have developed since the 1970s, but they are hard to discern. In their 2015 Harvard Design Magazine essay, “The Missing Link: Architecture and Waste Management ,” Hanif Kara, Andreas Georgoulias, and Leire Asensio Villoria point out that “drastic efficiency leaps, environmental impact improvements, and technological innovations all happen far from the public eye.” They argue that architects should be more deeply involved in making these visible by creating better-designed waste facilities. These would not merely soften the harsher aspects of waste infrastructure, they also could help turn public attention toward the multiple ways we dispose of material. “With their innovative programming, and welcoming and transparent architecture,” they emphasize, “these buildings help to promote healthier communities.” This is one important way to elucidate the problem of waste, but it doesn’t fundamentally challenge the system of consumption that creates it. Waste is still an end product.

Designers can also reconceive the consumption system in more subtle ways. As a circular economy develops, its goal of disposing of no material moves the challenge of waste more deeply into the system. Waste becomes as much a beginning as an end. In their book Building from Waste: Recovered Materials in Architecture and Construction , Dirk E. Hebel, Marta H. Wisniewska, and Felix Heisel question “whether the consideration of the waste state of a product should not become the starting point of its design proper.” In this view, waste becomes an essential concept in design, since the depleted value state of the material informs the process from the beginning.

Alternatively, designers could focus their attention on utilizing materials that have already been used. For now, however, designing with reused building materials can be challenging because they are not widely available. As Alejandro Bahamón and Maria Camila Sanjinés point out in Rematerial: From Waste to Architecture , “The design process for a building that incorporates recycled materials and products differs significantly from the conventional way of conceiving architecture…. The design team must first identify the sources of materials suitable for reutilization and then start to define the details.” While this shift in design process can drive creativity, the limited market for reused material can constrain innovation. As a circular consumption system develops, designers must continue to question conventional design processes, but they must also shift the ways they think about waste.

Over the past year, a number of GSD courses have directly addressed this challenge. Waste in its many manifestations was the central theme of the first-year courses in the Masters of Design Engineering program. In Architecture, the spring semester studio “Making Next to Forest” confronted the concept of a circular economy in Japan’s wood production industry. And several Landscape Architecture courses have focused on how urban sewage can support agricultural production and food systems.

Waste “is on some level unappealing,” points out GSD instructor Jock Herron. So, while waste may not necessarily be the big idea designers first turn to, it presents “lots of different design solutions,” difficult engineering challenges, and “big behavior elements.” Consequently, as a theme for the first-year course sequence in the MDE program, “it worked extraordinarily well.” Twenty-two students worked in multidisciplinary teams to unearth the huge challenges waste presents. Herron says that the program structure lends itself to broad investigations—“We give them the theme, and they figure out what the problem is”—but the research teams moved, over the course of the year, toward tightly focused and very specific design solutions.

During the fall semester, students worked with the faculty team of Andrew Witt, Joanna Aizenberg, Elizabeth Christoforetti, and Cesar Hidalgo to investigate multiple different kinds of waste—electrical, medical, nuclear, and so on—and the systems associated with them. Naturally, these intersect, and their interactions point out how waste occupies the complex interfaces between human and natural systems. Continuing with the theme into the spring semester, student teams worked with Jock Herron, Stephen Burks, Luba Greenwood, and Julia Lee on developing specific products to help contend with waste-related challenges.

Groups addressed a wide range of topics including noncompliance in medical regimens (which results in wasted medicine, economic resources, and human capital); waste of ink and paper in book publishing; furniture disposal by large and very mobile student populations; sources of food waste in agricultural production and at points of sale; efficiency in the complex timeline for liver transplants; the use of algae for carbon sequestration; and identification and disposal of trash in national parks. Each team designed a tangible product to deal with the challenge.

Coming at waste from a very different angle, Toshiko Mori’s “Making Next to Forest” spring semester studio started with the idea that waste “is a completely wrong notion.” “We really should not have any waste,” Mori emphasizes. Her studio focused on “a global approach to proposing alternative forest economies,” using wood production in Hokkaido, Japan as a model. Japanese resource usage is highly effective, in part because it balances natural forest management with industrial wood production that produces little waste. “In Hokkaido when they harvest trees,” Mori explains, “there’s only 10 percent waste. Ninety percent of everything they harvest is being used, even the small branches… they’ll be used for chopsticks, which makes sense. Even though the last 10 percent is unused, it could be used for biofuels.”

Students studied the processes that contribute to this highly efficient system, including natural resource preservation, timber harvesting, furniture building, and material reuse—both in Boston and while visiting Hokkaido for two weeks in February. Their first design included a masterplan for a forest research center on an abandoned university campus in the city of Asahikawa. The center’s primary purpose would be to promote a circular economic model—finding ways to make use of otherwise wasted wood, particularly byproducts of industrial processes. Their final project, a chair museum in the township of Higashikawa (a partner and sponsor of the studio), sought to connect the research on forest ecology with design at all scales, using regionally sourced materials.

Waste of another kind is the central focus of a GSD faculty team studying the complex interactions between Mexico City and the agricultural Mezquital Valley, about 37 miles northeast of the city. A massive pipe connects the city and the valley, pumping an almost incomprehensible volume of raw sewage into its highly productive soil. Wastewater nutrients support a rich agricultural economy, but modern sanitary standards of sewage treatment threaten the balance.

In their research proposal, “The Right to the Sewage: Digesting Mexico City in the Mezquital Valley,” which recently won a major prize from the SOM Foundation, Montserrat Bonvehi-Rosich, Seth Denizen, and David Moreno Mateos propose to undertake a systems-based multidisciplinary study that includes the whole waste-production cycle, with the goal of better understanding and supporting its productivity. Their 2019-2020 courses on food systems, ecosystem restoration, and soil formation offered a prelude to a future research and design studio that will address the challenges of waste disposal and reuse in Mexico City, and, more broadly, the future of the urban water cycle in cities throughout the world.

In multiple ways GSD faculty and students are challenging fundamental presumptions about waste and the economic models that make it necessary. By incorporating waste deeply into their thinking, and the products they envision, they are questioning design processes, reconceiving consumption, and finding new value in refuse.