Baku—like Dubai and other major cities flush from the oil industry—has seen an upsurge of foreign interest in recent decades, both in an influx of capital and in commissions of megastar architects. From the Flame Towers designed by HOK to Zaha Hadid’s monumental Heydar Aliyev Center, the high-profile new developments provide an international image for the city, which the Europe-focused Azerbaijani government is proud to claim.

Baku—like Dubai and other major cities flush from the oil industry—has seen an upsurge of foreign interest in recent decades, both in an influx of capital and in commissions of megastar architects. From the Flame Towers designed by HOK to Zaha Hadid’s monumental Heydar Aliyev Center, the high-profile new developments provide an international image for the city, which the Europe-focused Azerbaijani government is proud to claim.

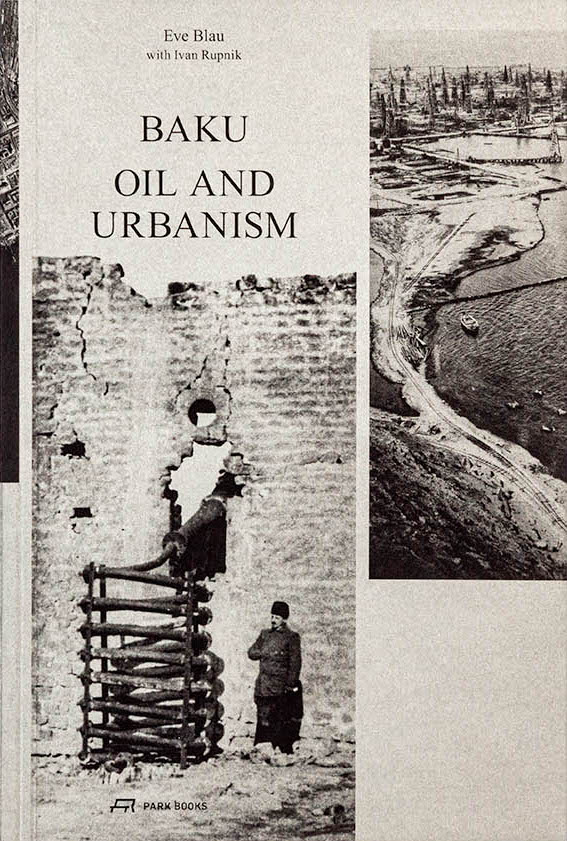

But as Eve Blau details in her new study, Baku: Oil and Urbanism–which received the 2019 DAM Architectural Book Award from Deutsches Architekturmuseum at the Frankfurt Book Fair and which features a photo essay by Iwan Baan–this contemporary reality is far from the dynamic cosmopolitanism that defined the region’s urban and intellectual atmosphere during its first oil boom in the pre-Soviet era, when it was the world’s leading producer of oil. The new development also demonstrates less cohesive planning than what been implemented by the Soviets when the city became a test case for urban innovation and experimentation. Instead, Baku now exemplifies development based on oil profit rather than a focus on the processes of its industry, the latter of which previously dictated much of Baku’s urban planning.

The arrival of Swedish arms manufacturers Robert and Ludvig Nobel in Azerbaijan in the early 1870s revolutionized the oil industry that until then had been underdeveloped, in large part because of the government’s monopoly on wells and reserves. Their primary innovations were sharing research with local engineers that they had gleaned from John Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, and the successful vertical integration of Baku’s oil industry. Beyond profit though, they introduced the notion of urban planning intimately linked to oil by providing housing and education to workers. They also constructed a public park in their Garden City development, Villa Petrolea, that contained an “extensive technical and cultural infrastructure for the managers and their families, including schools, a library, billiards, and meetings rooms, and the first telephone in Baku”—a style of comprehensive design for living on which the Soviets would expand.

This fusion of urbanism and oil influenced the construction of other developments, most notably the area known as Black Town that was established in the late 1800s. Both the first instance of zoning and the first “planned industrial zone” in Russia, Black Town became “one of the clearest instances of the knowledge spillover between urban and oil-production practices and the intersection of their distinctive spatial logics.” Here, the components of the oil industry, from pipelines and storage facilities to vats and railway tracks, became “subordinated to the urban.”

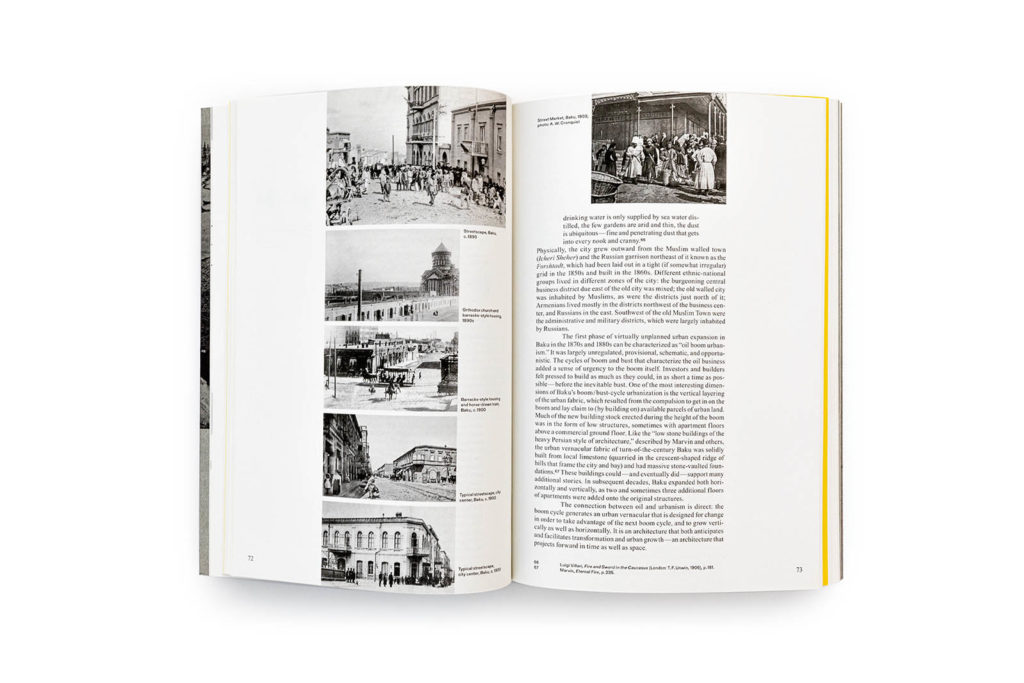

As Blau describes it, Black Town’s urban planning “attempted to rationalize the emerging oil industry in dense urban formation by compacting the apparatus of oil production into the traditional urban block, and organizing within the block the unwieldy infrastructure and noxious by-products of industry into the regular courtyard arrangement of the traditional urban workshop.” Though Black Town was unsanitary and generally poorly kept, the zone’s extreme density—which exacerbated these negative living conditions—was also central to fostering a diversity of thought. The resulting social and intellectual intensity spurred innovation and knowledge production—and, later, political unrest that undermined foreign interest in establishing oil industries in Baku and other densely populated areas.

In the 1880s, construction took off thanks to the rush-to-build psychology of the boom-and-bust oil industry, but also as a result of local oil barons’ goals for self-determination. The state now maintained a laissez-faire policy toward oil, and the barons owned the land on which it was found and therefore the oil they discovered under it. But because of their inability to participate in government due to bigoted Russian policies against Muslims, their influence was expressed by wielding “soft power.” They supported the local citizens and Azerbaijani culture more broadly by creating a host of institutions including major theaters, schools, parks, newspapers, hospitals, charitable organizations, museums, and more. These institutions contributed to Baku’s identity as the “Paris of the Caspian”—“a modern European city with broad tree-lined boulevards, a seaside esplanade, monumental public buildings, large new docks, electrical power, and modern communication networks.”

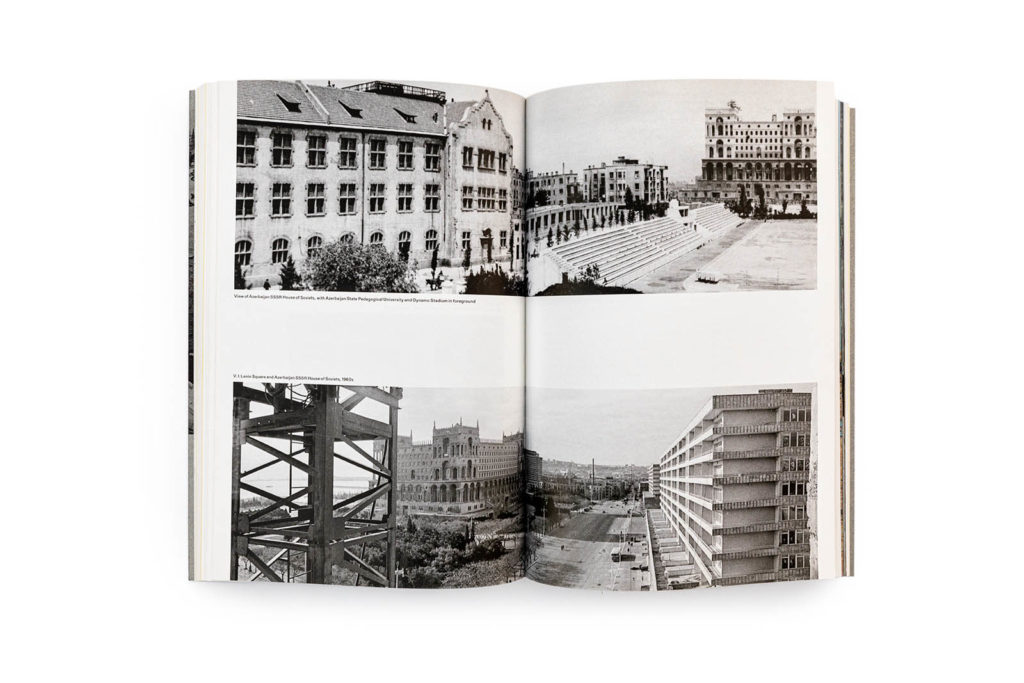

Oil would continue to function as a defining influence on Russian urban development in the Soviet Republic, in which the “City of Socialist Man” concept was developed in 1918. The desire for such a design template was derived from Engels and Marx’s antagonism toward the city for, among many reasons, the class antagonism it fostered. The first General Plan redefined the urban to include the regional—in Baku’s case, the Absheron Peninsula. This was a direct result not just of the Soviet desire to break city/country oppositions but because of the spread of the area’s oil fields. Its design was in turn only made possible because of the land surveys and other research performed throughout the area as a result of the Republic’s dependence on Baku’s oil.

One notable experiment from this General Plan was Armenikend, a zone situated “strategically between the sites of oil extraction and processing” and remarkable for its use of superblocks that consisted of “variously arranged apartment buildings…. grouped around garden spaces and communal facilities.” The latter included “technical and academic institutions, museums, and theatres, as well as markets, regional schools, community buildings, department stores, clubs, and sports facilities,” in addition to a sizable amount of “open space provided for collective use.”

Taken together, these new spaces served as an example of planning dictated in part by “communal logic”—a move that impressed Maxim Gorky, who in 1928 praised the integration of the workers into the cultural life of Baku. That logic would persist throughout the Soviet period as different leaders approved various urban experiments in the region, such as the world’s first offshore drilling facility, Neft Dashlari (Oily Rocks), which opened in 1949 and “housed thousands of oil works…in five- and nine-story apartment buildings that were linked with schools, libraries, shops, a bakery, clinic, cinema, sports facilities, and vegetable gardens.”

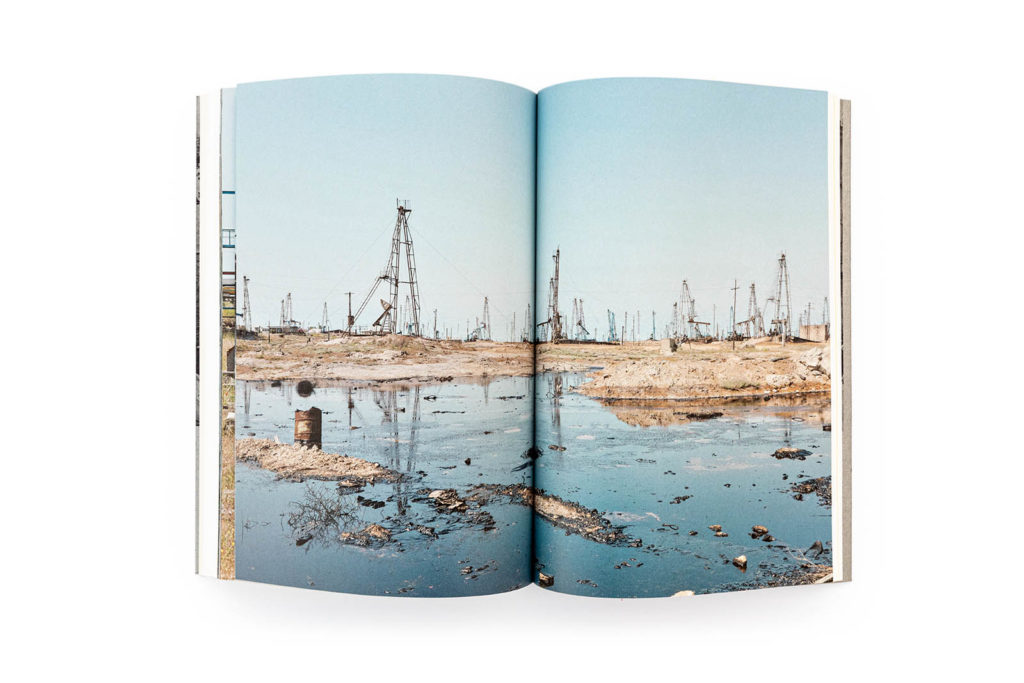

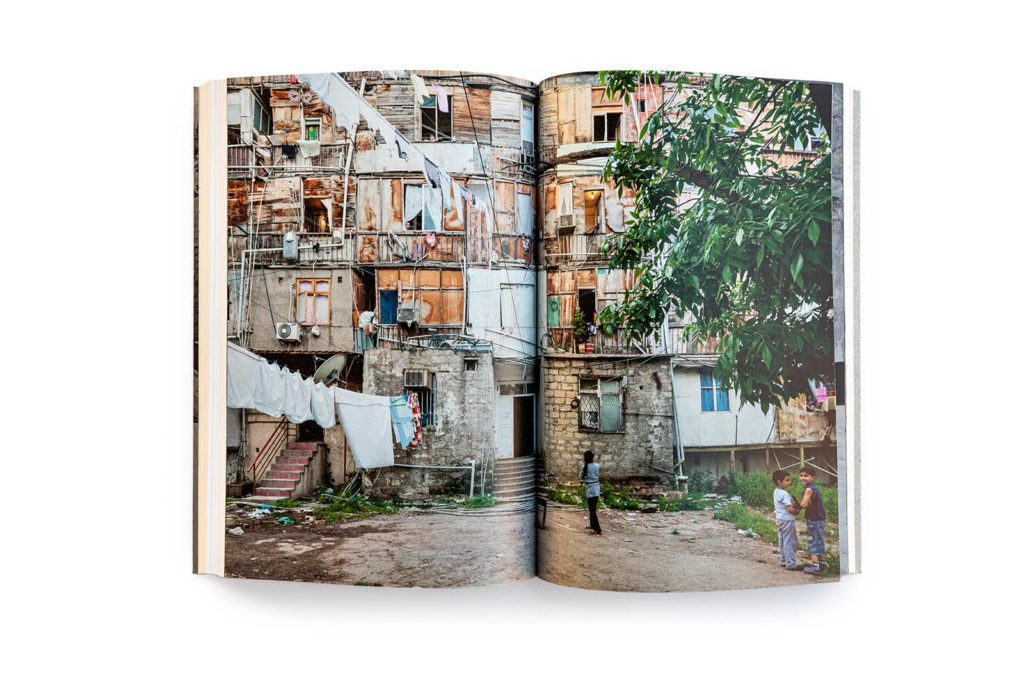

In the post-Soviet period, many of the once-thriving oil fields have become dilapidated, in part because Siberia became the center for the nation’s oil in the 1970s. Despite this, some legacy from the preceding century remains, from “the value put on research and the skills of scientists and engineers in the Soviet oil industry” to, arguably more critical, “the value placed on the welfare of the oil workers, which resulted in the vast urban and institutional infrastructure” throughout Baku. As Blau argues, “the most important legacy of the Soviet period there is the urban-industrial experiment begun in 1920—to plan oil and urbanism together—that shaped the lived experience of socialism in the city.”

The current ideology dictating Baku’s urbanism falls short of this legacy, according to Blau. Although foreigners are heavily investing in its oil industry, their actions are not accompanied by the exchange of ideas and knowledge that contribute to the development of a dynamic urban environment. Similarly, the prevalence of foreign architects does little to rejuvenate the cosmopolitan nature of the city whose population was once more foreign than Azerbaijani. Although there are green spaces and public areas, Blau implies that these are not created for the enrichment of Baku’s citizens as they would have been in the past. Instead, they are sites from which to view the high-rises and other shiny buildings that serve as a projection of an international spirit. It is imported internationalism rather than one enmeshed and embodied in Baku’s urban fabric.

The architectural vestiges of Baku’s development—“early capitalist, Soviet and post-Soviet”—persist, despite attempts to bulldoze that history. Oil’s infrastructure still permeates the city through the omnipresent pipelines that remain in use for the circulation of energy and water and which “wind through, over, and under city streets, into and around buildings, forming trellis-like archways over garage and driveway entrances, framing windows and doors.” They act as a visible reminder of the need for a logical, useful, and densely coordinated connective tissue that can support a diversity of people and ideas. After all, the inherent instability of the urban fabric has been the engine powering Baku’s ever-evolving innovation.