“When an area is empty, there’s a desire to fill it in—it’s the colonizing mindset,” says Angela Mayrina (MDes ADPD ’20). She recently won the 2020 Design Studies Thesis Prize for a 200-page project that responds to the Indonesian government’s intention to move the country’s capital from Jakarta—where she grew up—to East Kalimantan on the island of Borneo, within five years.

The plans are designed to help relieve the problems of Java, the island on which Jakarta is located—overpopulation and the fact that the city is rapidly sinking into the ocean—and to forge stronger connections with Indonesia’s eastern provinces, including those where there are separatist movements. In 2017, Mayrina reports, there were fewer than 95,200 people living on the land earmarked for the new capital; up to 2.75 million people are due to be relocated there after the move.

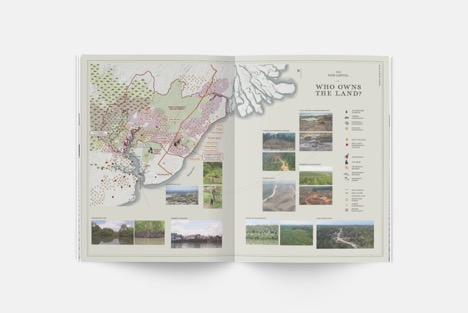

“I was intrigued by the political and media narrative around Kalimantan, because they talked a lot about how the move would help solve the problems of Java, but nobody was talking about Kalimantan—except to say that the government owns a lot of empty land there, on which it can build a new future,” Mayrina says. “But if you look on Google Maps, you’ll see that a lot of the area contains only patches of forest; in many parts of Kalimantan, this idea of it being empty, wild jungle is not real.”

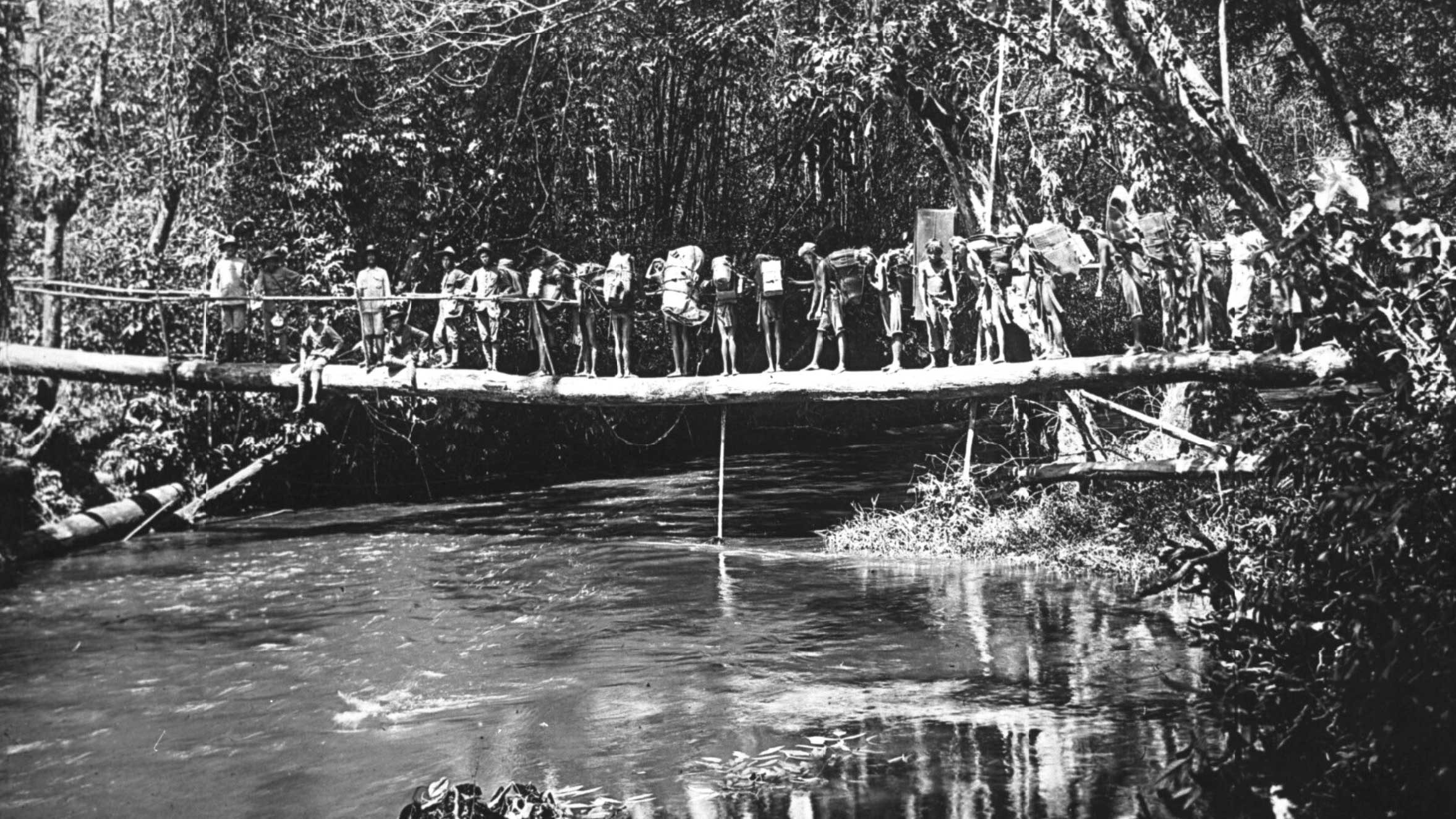

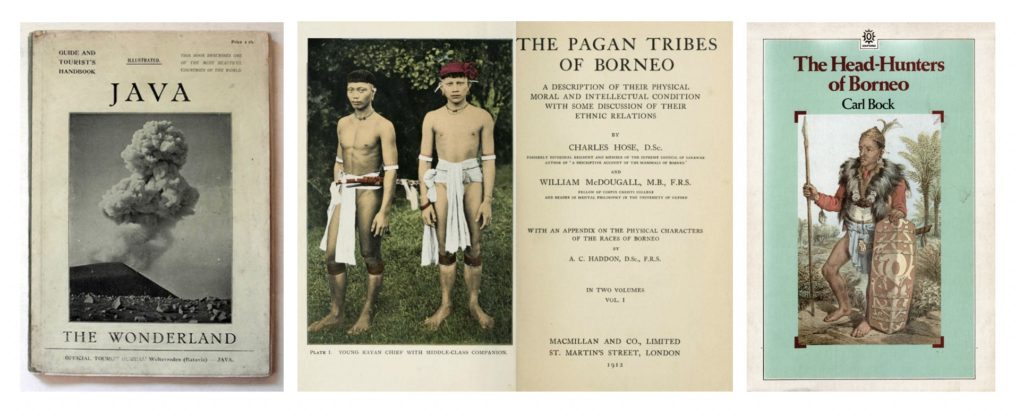

A Guidebook to an Empty Land: Kalimantan and the Shadow of the Capital City is a compendium of essays, archival material, images, and maps that challenges the image of Kalimantan as uninhabited, dense forest and spotlights the people who live there and the natural environment. The publication itself references the guidebooks published when the Dutch colonized the archipelago, which was when the notion of Kalimantan as empty was manufactured. Mayrina used the traditional format of the guidebook, while also challenging it—showing maps while also highlighting that they are limited and simplified interpretations of reality, for example. “The books I found in the Harvard library promoted tourism to Java, but the other islands were under-researched, so this idea of the interior as empty and Kalimantan as backward was embedded in the discourse about Indonesia from then,” she says, pointing to texts that painted Kalimantan as inhabited by wild animals, poisonous plants, and scary tribes.

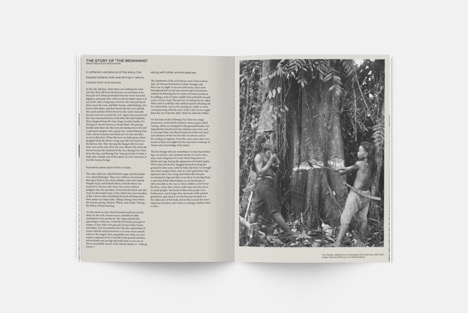

The trope of emptiness, she demonstrates, lends itself to development. The Dutch adopted the German scientific forestry method (which was used around the globe because it was so efficient), and brought in foresters to cultivate the land and categorize it for different uses. Subsequently—particularly since Indonesian independence in 1945—the Indigenous people of Kalimantan have been pushed out of the area by the oil, coal, timber, diamond, and gold industries. The desire to extract and exploit the area’s natural resources continues today. “Indigenous people like the Dayaks are still trying to map their land and make the government recognize their rights over the areas, and if the new capital moves there, they will be even more at risk,” Mayrina says.

There have been previous attempts to move people to Kalimantan from Java. In the 1970s, the post-independence government revived a colonial-era program called “transmigration,” under which landless people in Java were given plots on the other Indonesian islands, a few months’ worth of food and supplies, and resources for development. The law mentions that the program was meant to fill in the “empty areas” in the rest of the archipelago. But these newcomers—who were not guided by the government following the relocation—found the soil conditions to be too difficult for farming, so they ended up abandoning rice fields to make a living from the land in other ways. In East Kalimantan, the establishment of different extractive industries brought in more newcomers to the island in a short period of time. “It created a lot of conflict because many Indigenous people were pushed aside by the newcomers, who became the face of the government on the island,” Mayrina explains. The transmigration program eventually ended, but Mayrina points out parallels between that era and what is being done today: “The capital city move itself is an iteration of transmigration.”

She says that NGOs report mixed feelings in Kalimantan about the move: on one hand, local people can see that it’s a change from years of being neglected by the government; on the other, development presents threats to the environment and their livelihoods, including the prospect of competing with and having to catch up to more developed parts of the country.

There are other dangers to moving the capital, Mayrina points out: the threat to biodiversity in Borneo and to endangered species such as orangutans, for example. Then there are the difficulties of cultivating the land and the dangers of building a new city on areas that have been deforested and on peat swamps, which pose a fire risk.

All this makes it even more crucial that Indigenous people, with their knowledge of the terrain and conditions, are involved in the conversation about the development of Kalimantan. “There’s a lot of knowledge that the Dayaks have about the land—how to cultivate it and manage it, with its ecological limitations—but they are continuously being pushed aside by the government,” Mayrina says. “Why not involve them in the conversation and conserve their knowledge, rather than imposing knowledge from elsewhere?” So far, she has mostly witnessed a top-down approach to consultation. “They are talking to elite groups in Kalimantan, but not to the people who will be most affected by the move.”

In putting together her project, Mayrina visited Kalimantan twice. Since then, she has been awarded a research grant, which she will use to involve NGOs working in Kalimantan that are fighting for official recognition of the Indigenous peoples’ rights to their land—a process that may now have more time because of delays to the project caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

At the same time, she is striving to bring greater awareness to these issues by speaking to publishers about distributing A Guideboook to an Empty Land and giving lectures. “The resources, the nature, the people—everything is interconnected, which is a perspective that’s missing in a lot of the conversation,” Mayrina says. “My goal is to bring these stories and these complexities to attention.”