As the world ground to a halt in the spring of 2020, with the COVID-19 pandemic shuttering shops, schools, subways, and offices, a street in Queens opened itself up as a new site of social infrastructure. [1] Located in Jackson Heights, one of the most congested neighborhoods in New York City with among the least green space per capita, a 26-block stretch of 34th Avenue was transformed into a 1.3-mile-long “vertical park” by the grassroots 34th Ave Open Streets Coalition. For 12 hours a day, every day, the street closed down to cars, permitting weary workers, solo-living seniors, and working-from-home parents and their children to stretch their legs, join in socially distanced exercise classes, swing by a community-led food pantry, or tend to a communal median garden that was—finally—their own.

Heralded as a visionary prototype for a more equitable and sustainable future city, the project also underscored the importance of civic space in an era marked by increasing privatization of the public realm. Reclaiming the street within a pandemic that both exposed and exacerbated the stark inequities of access to healthcare, community support, and green space across the United States framed the necessity of such spaces, in the words of sociologist Eric Klinenberg, as a matter of life or death. [2] In a keynote lecture recently delivered at the GSD, Klinenberg highlighted 34th Avenue as a success story within a larger domestic policy movement toward an expanded definition of infrastructure, in part fueled by the pandemic. “The pandemic forced us to hunker down and maintain physical distance,” says Klinenberg. “But we also developed newfound appreciation for gathering places that we had taken for granted. My hope is that we channel that into support for social infrastructure. We’re living through a unique moment, and we’re poised to make transformative investments in the physical systems that sustain us.”

Such an investment may begin through the Biden administration’s Build Back Better framework. Viewed as one of the most significant domestic policy agendas since the New Deal of the 1930s and the Great Society of the 1960s, Biden’s original $3 trillion BBB plan comprises two pieces of legislation: the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill, signed into law on November 15, and the $1.75 trillion Build Back Better (BBB) bill, which remains stalled after a firm rebuke from Senator Joe Manchin.

The infrastructure bill (also called the public works law) addresses what we typically think of as infrastructure, and offers the largest investment in the sector in over a decade. It includes funding for repairing and expanding roads, bridges, mass transit, and rail service, as well as upgrades to ports, electric grids, and water infrastructure. It casts a wide net across the country, including the replacement of lead pipes in Illinois, bridge repairs in Massachusetts, regional transit connections in Louisiana, and abandoned mine cleanup in Kentucky. In addition to bolstering material infrastructure, the bill hones in on the so-called “digital divide,” funneling $65 billion into expanding broadband access to rural and disadvantaged communities in the US.

The controversial BBB bill—focusing on what it terms “human infrastructure,” or social infrastructure—includes allocations of $150 billion for new affordable housing, $550 billion for climate-related policy and programs, $18 billion for universal pre-K, and $200 billion for childcare. For political reasons, however, many of these provisions will be absent from the bill, if it ever clears the senate. Both bills are the first pieces of federal legislation in over a decade to address the climate crisis and suggest solutions for mitigating the impact of global heating.

Across both bills, the idea of infrastructure expands to include social reform, digital telecommunications networks, climate justice, clean energy, and affordable housing. In addition to Klinenberg’s keynote, multiple studios and seminars at the GSD last term attempted to grapple with this multifaceted understanding of infrastructure. “That the Biden bill recognizes and supports social infrastructure, the economies of care, and reproductive labor, particularly at the household scale, is an exciting step for a country wherein everything has been relentlessly privatized,” says Malkit Shoshan, who taught “Reimagining Social Infrastructure and Collective Futures” in the fall. “By strengthening the household economy, stronger households can better interact with other households and create a commons. These issues should be essential to talking about the future of infrastructure—that it’s a matter of the values we preserve as a society.”

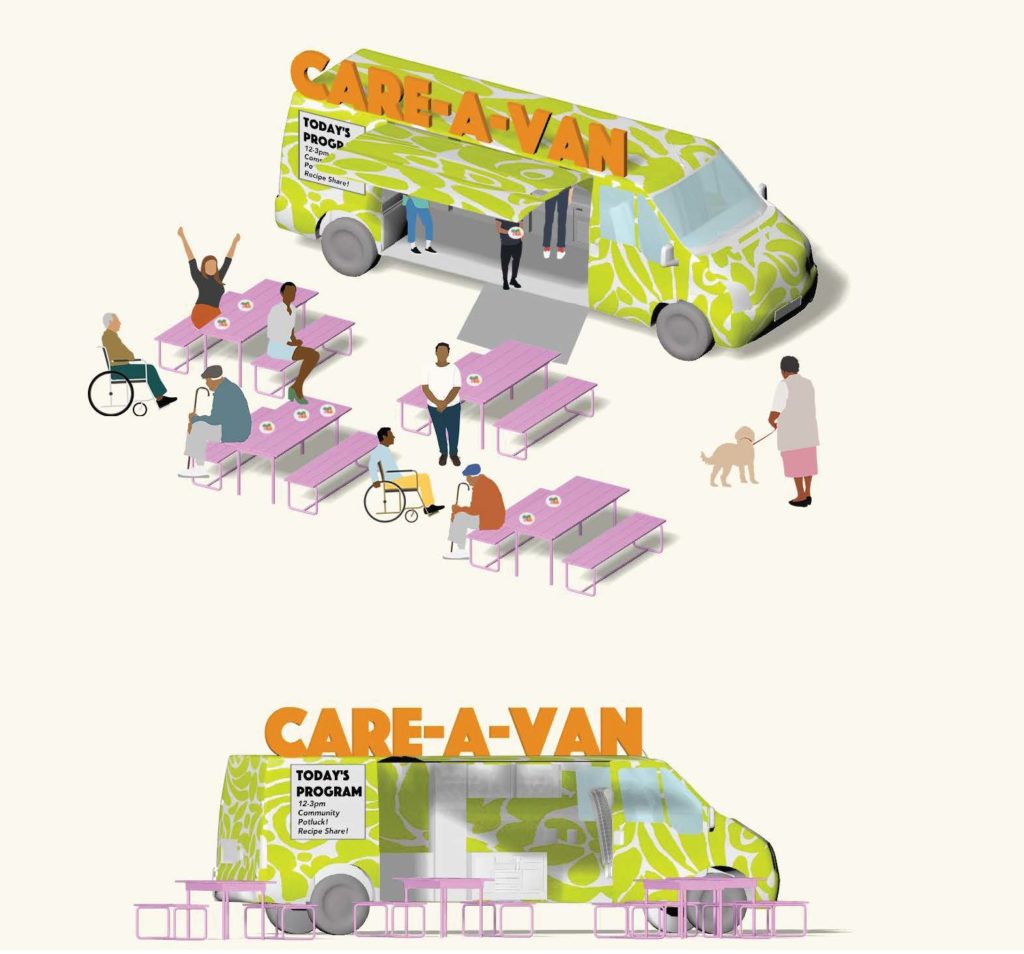

Shoshan framed her project-based seminar with key theories intersecting the social sciences, economics, feminist theory, and ecology, including those of economist Kate Raworth, author of Doughnut Economics, and philosopher Sylvia Federici, whose writings on reproductive labor have found new relevance during the pandemic. Students were asked to envision a more intersectional social infrastructure, where the well-being of mothers, caregivers, the elderly, and other marginalized groups, as well as precarious public services, were integrated into a collective future vision of a healthier planet. Among the projects to emerge from the seminar was a reimagining of the post office infrastructure, which is at risk of privatization, as well as a mobile “Care-a-Van” that revitalizes the lives of the elderly and reintegrates them into public spaces, generating new social networks. A “school for the future” sought to support an underserved public high school in East Boston, the largest in the area, in a neighborhood expected to be flattened by sea-level rise as early as 2050. In addition to providing climate infrastructure, the project proposed opening up the physical infrastructure to community use in after-school hours.

Ron Witte’s studio, “ROOM,” took a micro-scale lens to the question of what constitutes good social infrastructure, from the design perspective of the public interior. Utilizing a new reading room for the Central Boston Public Library as a case study, students were asked to envision alternative design protocols for indoor institutional spaces in an era where the role of such spaces is expanding as social infrastructure. Proposals varied widely, from reimagining the cultural status of the library to a “high-tech medium,” where visitors are given a window into the guts of archival space through a series of tubes transporting reading materials, to cracking the institution open like an egg, making its processes visible from the outside and expanding the internal boundaries of the building. “Architecture has been pushed to the side in this conversation around the future of infrastructure,” says Witte. “We’ve tended to focus on broad questions around social infrastructure, economies, and public spaces, but without architecture to prompt them into a new state, nothing will happen.”

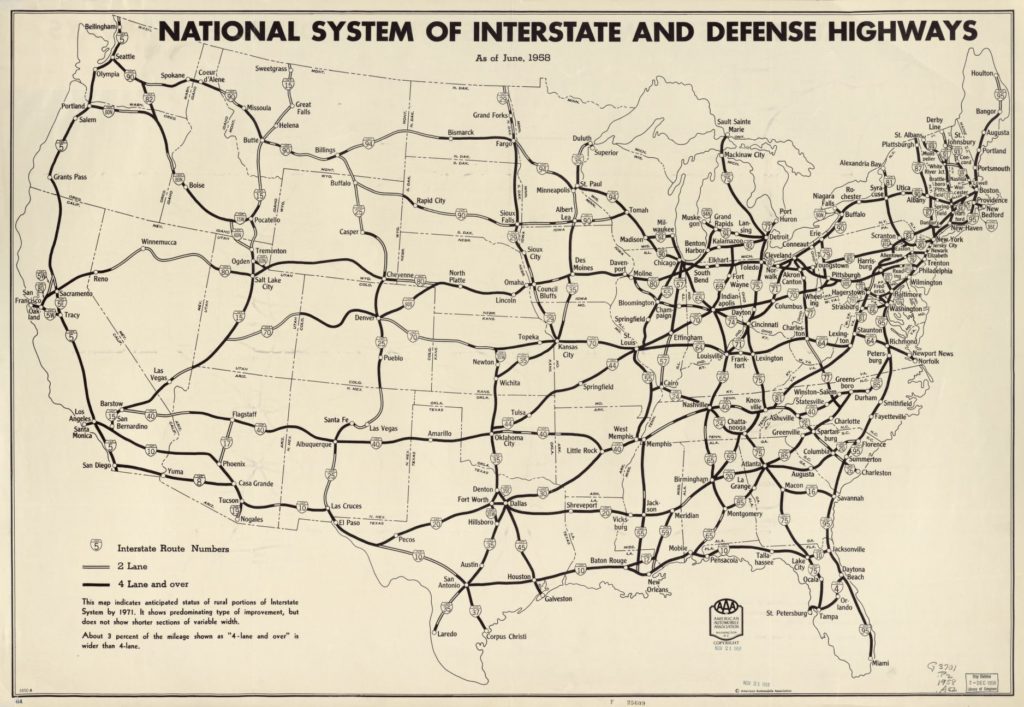

Additional federal efforts are necessary to ensure the Building Back Better framework’s climate resilience funds meet those who need it most. The new White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council is a step in the right direction, with 26 leaders from diverse communities appointed to judge applications for community-led climate infrastructure projects. [3] But there must also be increased support at the local level, to ensure these communities have no barriers to accessing funds and can realize these projects collaboratively. Responding to this condition, Dan D’Oca’s fall studio, “Highways Revisited,” was an exercise in reimagining the future of 10 cities and their surrounding highway systems. Each student was connected with a local activist or government official to envision an alternative use for that highway infrastructure while taking stock of its historical damage to disadvantaged communities.

Whittled down from a short list of 50 areas, the selected sites cover a wide range of topologies and racial and socioeconomic spectrums—they include El Paso, the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston, Detroit, Oakland, and New Orleans. “The idea was to find examples of cities where there was already a conversation about highway removal, but where things weren’t so settled,” explains D’Oca. “It was important for students to be able to think big and dream, but also have the guidance of a good liaison, and the tenability of a pitch process.”

When you destroy a neighborhood you don’t just destroy homes, you destroy vehicles for amassing generational wealth.

Dan D’Oca

With guidance from a lifelong resident of the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans (one of the oldest Black neighborhoods in the US, and the birthplace of jazz), one student transformed a stretch of I-10 that decimated the neighborhood into a powerful piece of community infrastructure, complete with public housing, green space, events programming, and an arts and music venue. (The White House has proposed removing the expressway altogether). For El Paso, another student nixed the freeway running along the US-Mexico border, restoring the original landscape of a green river valley and building a new neighborhood alongside it. In the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, a student worked with local liaisons to envision the removal of an eight-mile stretch of I-94, replacing it with a parkway, a rapid transit system, and new neighborhoods. The studio explored the emerging concept of “right to return,” currently piloted by the city of Santa Monica, which specifies Black communities displaced by mid-century urban renewal policies should be at the front of the line in new affordable housing markets. “When you destroy a neighborhood you don’t just destroy homes, you destroy vehicles for amassing generational wealth,” explains D’Oca. “So this idea of a ‘right of return’ being implemented by some local policymakers integrates the idea of infrastructure as an opportunity for reparations.”

Tom Oslund and Catherine Murray’s studio, “Harnessing the Future,” looked beyond the US to address the social, ecological, and economic entanglements of digital infrastructure in the small west Irish town of Asketon and the surrounding Shannon Estuary, where a new data center is slated for development. With a local environmental engineer as steward, students were tasked with reimagining the design of the data center to support the local economies and histories of Ireland, while adhering to the region’s strict conservationist protocols, and achieving carbon neutrality. One of the proposals utilized the energy of cow waste and Atlantic wind turbine production to fuel the data center. Another restricted its size and energy consumption to the amount of energy needed to churn Ireland’s signature domestic export, Kerrygold butter (and recycling the energy to do so). And the third proposal divvied up the area into wind energy–producing parcels of land owned by locals to sell back to data providers, flipping the power hierarchy between opportunistic data companies and residents. Oslund cites the main challenge with equivalent projects in the US as “a problem of too much land and too little restraint”—but is optimistic that an industry-led initiative for ecological design alternatives could catch on across the Atlantic. “The paradigm change that must happen is the responsibility of these companies,” he says. “Data centers have already surpassed airlines in carbon emissions, and there’s too much at stake. This studio was put in place to showcase more environmentally conscious design alternatives that support local economies and culture.”

As the future of the BBB remains uncertain, and the real work of the Infrastructure Bill lies ahead, it’s crucial that in expanding our definition of infrastructure, we take care not to divide it. A truly democratic approach to infrastructure acknowledges its constituency and responsibility across all sectors and publics: in other words, digital infrastructure must be social infrastructure; climate resilience infrastructure must also impart a civic value. Closing out his keynote lecture, Klinenberg gave a simple example for how this might be achieved: by revamping the design of a levee, which will be an increasingly common piece of infrastructure amid rising sea levels, to include a public park on top. What’s required is a crucial shift of perspective that enables new infrastructure. As Oslund says, it needs to “provide the same function, but allow for a different story.” There must be a design sensitivity on both a micro and macro scale to ensure it benefits those it has a particular duty to serve. The future of infrastructure requires a feminist design approach that centers marginalized groups; an equitable approach that incorporates reparations to communities who bore the damage wrought by earlier infrastructure projects; an ecological approach that acknowledges the stakes of the climate emergency; and the support of a public resource system that ensures the longevity of grassroots initiatives. Despite its warranted criticisms, the BBB framework offers a vital first step in this direction. Now, it’s up to designers and policymakers to get to work.

[1] In his book, Palaces for the People, sociologist Eric Klinenberg defines social infrastructure as a loose category of public places—parks, playgrounds, libraries, and town halls, as well as grocery stores, cafés, and barber shops—that are the spatial glue of a healthy society. Formal and informal, organized and happenstance, these are the hang-out spots where communities are made and people learn to look out for each other, particularly in times of crisis.

[2] Klinenberg’s acclaimed research on the “high resilience” areas of the 1995 Chicago heatwave pinpoints the significance of robust social infrastructure in contributing to low death tolls in otherwise demographically similar neighborhoods.

[3] Both bills intend to jumpstart the Justice40 Initiative ordered by Biden just days after taking office. It outlines that 40 percent of federal climate spending must reach underserved areas (formally defined as low income, rural, and/or communities of color), as a climate justice initiative. Despite these promises, critics argue this money will largely benefit middle-class, white communities.