The GSD Announces 2025–2026 Faculty Promotions

The Harvard Graduate School of Design announces four faculty promotions: Sean Canty to Associate Professor of Architecture, Jungyoon Kim to Associate Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture, Pablo Pérez-Ramos to Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture, and Sara Zewde to Associate Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture.

Sean Canty (MArch ’14) is an architect and educator whose work explores the capacity of architectural form to reorganize spatial norms and forms of social life. He is the founder of Studio Sean Canty (SSC), a Cambridge-based, independent architecture practice that introduces novel geometries and materials to enrich the spaces of everyday life. Working across domestic, cultural, and civic programs, SSC’s design approach incorporates drawing, model-making, and immersive visualization to choreograph spatial adjacencies that balance solitude and collectivity. Canty is also a cofounder of Office III, a design collective with offices in New York, San Francisco, and Cambridge. The group was a finalist in the 2016 MoMA PS1 Young Architects Program and designed the Governors Island Welcome Center. Their work has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art and other venues. Canty has taught or coordinated Architecture Core design studios since his first appointment at the GSD in 2017 and offers courses in design media and techniques. His pedagogy emphasizes abstraction, representation, and typological invention, drawing connections between architectural form, spatial organization, and visual communication. Prior to the GSD, Canty held teaching appointments at the Cooper Union, UC Berkeley, and California College of the Arts. His work has been exhibited internationally, including at the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, The Cooper Union, and A83 Gallery, and his writing has appeared in Harvard Design Magazine, Log, Domus, MAS Context, and several edited volumes. His accolades include the 2023 Arts and Letters Award in Architecture from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the 2023 Architectural League Prize, and the 2020 Richard Rogers Fellowship from Harvard. He holds an MArch from the GSD and a BArch from California College of the Arts.

Jungyoon Kim (MLA ’00) is a practicing landscape architect, registered in the Netherlands and in Massachusetts. She founded PARKKIM with Yoonjin Park in Rotterdam in 2004 and relocated to Seoul in 2006. PARKKIM PLLC recently opened in Massachusetts with the goal of expanding its practice beyond Korea. PARKKIM has completed a wide variety of projects that range in scale and nature, including high-profile corporate landscapes and civic venues. Notable completed projects include the Seoul Museum of Craft Art (2021), Hyundai Motor Group Global Partnership Center and University Gyeongju Campus (2020), Plaza of Gyeonggi Provincial North Office (2018), CJ Blossom Park (2015), and Yanghwa Riverfront (2011). Their ongoing projects include Suseongmot Lake Floating Stage in Daegu, Korea, for which PARKKIM won the international invited competition in 2024 and is to be completed in 2026. She published the book Alternative Nature (2015), co-authored with Park, a compilation of articles written by the two principals since 2001. The term “alternative nature” was first presented in their essay “Gangnam Alternative Nature: the experience of nature without parks,” featured in the book Asian Alterity (2007), edited by William Lim, rethinking the concept of “natural” within the context of contemporary East Asian urbanism. Upon her GSD appointment, Kim has expanded PARKKIM’s design research into seminar courses and option studios, including “Lost and Alternative Nature: Vertical Mapping of Urban Subterrains for Climate Change Mitigation.” Kim was selected as “Design Leader of Next Generation” (2007) awarded by the Korean Ministry of Commerce and appointed to “Seoul Public Architect” (2011) by the Metropolitan Government Seoul. She received an MLA from the GSD and a BAgric in landscape architecture from Seoul National University with distinction.

Pablo Pérez-Ramos (MLA ’12, DDes ’18), is a licensed architect from the Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid (ETSAM); he coordinates the first-semester Landscape Architecture Core studio and teaches research seminars and lecture courses in landscape theory. Pérez-Ramos’s research explores the reciprocal relationship between design and the natural sciences, using landscape form as a medium to interpret both physical processes and abstract scientific concepts. With interests in material culture, the environmental humanities, and the philosophy of science, he has delved into the origins of ecological narratives in contemporary landscape architecture, and more recently expanded his focus to include thermodynamics, biological systematics, and evolutionary theory. His theoretical agenda underpins ongoing research on climate adaptation, traditional knowledge, and agroecological practices in conditions of extreme heat and aridity. His work is ultimately concerned with the formal tensions and interferences existing between human technology and the other physical forces and processes—tectonic, atmospheric, biological—that shape landscapes. Prior to his GSD appointment, Pérez-Ramos taught at the Northeastern University School of Architecture, Boston Architectural College, and Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid. Between 2012 and 2016, he served as regional planning coordinator for the 2025 master plan for the Metropolitan District of Quito and previously practiced as a licensed architect in Madrid. His writings have been published in the Journal of Landscape Architecture (JoLA), The International Journal of Islamic Architecture (IJIA), PLOT, MONU, Revista Arquitectura (COAM), Landscape Research Record (CELA), and in the edited volumes The Landscape as Union between Art and Science: The Legacy of Alexander von Humboldt and Ernst Haeckel (2023), and MedWays Open Atlas (2022), among others.

Sara Zewde (MLA ’15) is founding principal of Studio Zewde, a design firm practicing landscape architecture, urbanism, and public art. Recent and ongoing projects of the firm include the Dia Beacon Art Museum landscape in Beacon, New York; the Watts Towers Arts Center landscape in Watts, Los Angeles; Cuyahoga Valley National Park in Ohio; and the Studio Museum in Harlem. Zewde’s practice and research start from her contention that the discipline of landscape architecture is tightly bound by precedents and typologies rooted in specific traditions that must be challenged. Without rigorous investigation, Zewde contends that these cultural assumptions will silently continue to constrict the practice of design and reinforce a quiet, cultural hegemony in the built form of cities and landscapes. Her projects exemplify how sensitivities to culture, ecology, and craft can serve as creative departures for expanding design traditions. Prior to joining the GSD in 2020, Zewde held faculty appointments at GSAPP, Columbia University, and the University of Texas School of Architecture. She holds an MLA from the GSD, an MCP from MIT, and a BA in sociology and statistics from Boston University. She regularly writes, lectures, and exhibits her work, and she is currently writing a manuscript based on her research of Frederick Law Olmsted’s travels through the Slave South and their impact on his practice. The book will be published in 2027 with Simon & Shuster. Zewde was named the 2014 National Olmsted Scholar by the Landscape Architecture Foundation, a 2016 Artist-in-Residence at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, and a United States Artists Fellow in 2020. More recently, she was named to the 2024 TIME 100 Next and *Wallpaper’s 300 People Shaping Creative America.

2021 Graduating Student Award Recipients

Each year at commencement, the Harvard Graduate School of Design confers awards on graduating students who demonstrate exceptional scholarly achievement, leadership, and service. Congratulations to the student award recipients, and to all of the 2021 graduates for your tremendous accomplishments.School-wide Awards

Gerald M. McCue Medal: Robert Morris Levine (MDes ADPD ’21)

The Gerald M. McCue Medal is awarded each year to the student graduating from one of the school’s post professional degree programs who has achieved the highest overall academic record.Digital Design Prize: Matthew Pugh (MArch II ’21) for “Animated Spaces, Creature-Like Objects: Animistic Interactions With Smart Buildings + IOT Objects”

Digital Design Prize: Ana Gabriela Loayza Nolasco (MArch II ’21) for “Center – Periphery: Encoding New Processes in Shenzhen’s Boundaries”

The Digital Design Prize is presented by the Graduate School of Design to the student who has demonstrated the most imaginative and creative use of computer graphics in relation to the design professions.Plimpton Poorvu Prize: Ian Grohsgal (MArch I ’21), Sarah Fayad (MLAUD ’20), and Dixi Wu (MDes REBE/ MArch I ’22) for “Building a Scalable Business in Data Centers”

The Plimpton-Poorvu Design Prize recognizes the top team or individual for a viable real estate project completed as part of the GSD curriculum that best demonstrates feasibility in design, construction, economics, and in fulfillment of market and user needs.Clifford Wong Prize in Housing Design: Isabel Dunham Strauss (MArch I ’21) for “Up from the Past: Housing as Reparations on Chicago’s South Side”

Clifford Wong Prize in Housing Design: Shaina Yang (MArch I ’21) for “Cripping Architecture”

The Clifford Wong Prize in Housing Design aims to help re-establish the essential role of architects in society to provide not only the fundamental needs of human shelter but to meet the challenge of designing creative solutions for improving living environments. The Prize is awarded for the multi-family housing design that incorporates the most interesting ideas and/or innovations that may lead to socially-oriented, improved living conditions.Peter Rice Prize: Erin Linsey Hunt (MDes Tech ’21) and Yaxuan Liu (MArch I ’21) for “NuBlock“

The Peter Rice prize honors students of exceptional promise in the school’s architecture and advanced degree programs who have proven their competence and innovation in advancing architecture and structural engineering.Sinclair Kennedy Traveling Fellowship: Brittany Alexis Giunchigliani (MLA I ’21) for study in Galicia, Spain

Sinclair Kennedy Traveling Fellowship: Sam E. Valentine (MLA II ’21) for study in Brazil and Africa

The Sinclair Kennedy Traveling Fellowships support a full academic year of research at destinations outside of the United States.Fulbright Grant: Sam E. Valentine (MLA II ’21) for study in Brazil and Africa

Fulbright Grant: Ciara Stein (MLA I/MUP ’21) for study in Kosovo

The Fulbright US Student Program is an international exchange program in the fields of education, culture, and science, offering advanced research, study, and teaching opportunities in over 140 countries.Alumni Award: Deanna Van Buren (Loeb Fellow ’13), Jack Dangermond (MLA ’69), and Everett Fly (MLA ’77)

The inaugural Alumni Award honors outstanding leadership by GSD alumni, underscoring that our students don’t stop being amazing after they graduate.Architecture Awards

American Institute of Architects Medal: Hannah Connolly Hoyt (MArch ’21)

The American Institute of Architects Medal is awarded to a professional degree student in the Master in Architecture graduating class who has achieved the highest level of excellence in overall scholarship throughout the course of their studies.Alpha Rho Chi Medal: Kofi Akakpo (MArch I ’21)

The Alpha Rho Chi Medal is awarded to the graduating student who has achieved the best general record of leadership and service to the department and who gives promise of professional merit through their character.James Templeton Kelley Prize MArch I: Shaina Yang (MArch I ’21) for “Cripping Architecture”

James Templeton Kelley Prize MArch I: Calvin Ray Boyd, II (MArch I ’21) for “Pair of Dice, Para-dice, Paradise; A Counter-Memorial to Police Brutality”

James Templeton Kelley Prize MArch II: Yuming Feng (MArch II ’21) for “American Brick and the Difficult Whole”

The James Templeton Kelley Prize recognizes the best final design project submitted by a graduating student in the architecture degree programs.Julia Amory Appleton Traveling Fellowship in Architecture: Hannah Connolly Hoyt (MArch ’20)

The Julia Amory Appleton Traveling Fellowship is given to a student in the Department of Architecture on the basis of academic achievement as well as the worthiness of the project to be undertaken.Kevin V. Kieran Prize: Arta Perezic (MArch II ’21)

The Kevin V. Kieran Prize recognizes the highest level of academic achievement among students graduating from the post-professional Master in Architecture program.Dept. of Architecture Faculty Design Award MArch I: Anna Kaertner (MArch I ’21)

Dept. of Architecture Faculty Design Award MArch I: Sarah Sum In Cheung (March I ’21)

Dept. of Architecture Faculty Design Award MArch II: Zhonghan Huang (MArch II ’21)

The Department of Architecture Faculty Design Award was established by the faculty of the Department of Architecture with the aim of recognizing significant achievement within a body of design work completed by a student at the GSD. This award is given to graduating students from each of the department’s two programs.Landscape Architecture Awards

Thesis Prize in Landscape Architecture: Gracie Villa (MLA I ’21) for “City|Forest: Reordering Plant-Human Relationships Towards Healthy Cities”

Thesis Prize in Landscape Architecture: Joanne Li (MLA I ’21) for “Ovis Versatilis: Icelandic Sheep Farm as Land Art Museum and Evolution Lab”

The Landscape Architecture Thesis Prize is given to the graduating student who has prepared the best independent thesis during the past academic year.American Society of Landscape Architects Certificate of Merit: Shira Grosman (MLA/ MDes ULE ’21)

American Society of Landscape Architects Certificate of Merit: Maxwell Smith-Holmes (MLA I ’21)

American Society of Landscape Architects Certificate of Honor: Kira Bre Clingen (MLA I/MDes RR ’21)

American Society of Landscape Architects Certificate of Honor: Koby Moreno (MLA ’21)

Each year the faculty in the Department of Landscape Architecture nominates students for the American Society of Landscape Architecture Awards2020 Landscape Architecture Foundation Olmsted Scholar: Jaline Esther-Mae McPherson (MLA I ’21)

Each year the faculty in the Department of Landscape Architecture nominates a student for the Landscape Architecture Foundation Olmsted Scholars Program. The program recognizes and supports students with exceptional leadership potential.Norman T. Newton Prize: Brittany Giunchigliani (MLA I ’21)

The Norman T. Newton Prize is given to a graduating landscape architecture student whose work best exemplifies achievement in design expression as realized in any medium.Pete Walker & Partners Fellowship for Landscape Architecture: Gena Morgis (MLA II ’21)

Pete Walker & Partners Fellowship for Landscape Architecture: Dominic Baitoo Riolo (MLA I ’21)

The Peter Walker and Partners Fellowship for Landscape Architecture is awarded to support travel and study for a graduating GSD student to advance their understanding of the body of scholarship and practices related to landscape design.Jacob Weidenmann Prize: Alysoun Irwin Wright (MLA I AP/ MUP ’21)

The Jacob Weidenmann Prize is awarded to the student of the most distinguished design achievement graduating from the Department of Landscape Architecture.The CELA Fountain Scholar Program: Jaline Esther-Mae McPherson (MLA I ’21)

The CELA Fountain Scholar Program is an endowed annual award in recognition and support of Black, Indigenous, and persons (students) of color in landscape architecture with exceptional design skills and who use their skills and ideas to influence, communicate, lead and advance design solutions for contemporary issues in a manner aligned with the original goals of Dr. Charles Fountain.Charles Eliot Traveling Fellowship in Landscape Architecture: Ciara Stein (MLA I/MUP ’21)

The Charles Eliot Traveling Fellowship is awarded annually as the highest honor by the Department of Landscape Architecture to one of its graduates.Urban Planning and Design

Academic Excellence in Urban Planning: Anna Carlsson (MUP ’21)

Academic Excellence in Urban Design: Alia Bader (MAUD ’21)

The Award for Academic Excellence in Urban Planning and Urban Design honors graduating students from each of the programs who have achieved the highest academic record.Award for Outstanding Leadership in Urban Planning: Kyle Miller (MUP ’21)

Award for Outstanding Leadership in Urban Planning: Alia Bader (MAUD ’21)

The Award for Outstanding Leadership in Urban Planning and Urban Design honors graduating students from each of the programs who have demonstrated outstanding leadership during their time at the Graduate School of Design.Urban Planning Thesis Prize: Mary Louise Chatters Taylor (MUP ’21) for “Urban Planning and Mental Wellness in Black Communities”

Urban Design Thesis Prize: Adam Mekies (MLAUD ’21) for “Aggregate, Aggregation + Geotechnical Urbanism”

The Department of Urban Planning and Design Thesis Prize is given to the graduating students in each of the programs who have prepared the best independent theses during the past academic year.The Award for Excellence in Project-Based Urban Planning: Anne Lin (MUP/MPH ’21)

The Award for Excellence in Project-Based Urban Planning is given to students who have demonstrated exceptional ability in urban planning projects including research and design studios throughout their course of study.The Award for Excellence in Urban Design: Christopher D’Amico (MAUD ’21)

The Award for Excellence in Urban Design is given to students who have demonstrated exceptional design ability throughout their course of study in the Urban Design program.American Institute of Certified Planners Outstanding Student Award: Steven Yuan Gu (MUP ’21)

The American Institute of Certified Planners Outstanding Student Award recognizes outstanding attainment in the study of planning by students graduating from accredited planning programs. The recipient of the award is chosen by a jury of planning faculty at each school.Ferdinand Colloredo-Mansfeld Prize for Superior Achievement in Real Estate Studies: Jiae Hasina Azad (MUP ’21)

Ferdinand Colloredo-Mansfeld Prize for Superior Achievement in Real Estate Studies: Julian Martin Huertas (MUP ’21)

Ferdinand Colloredo-Mansfeld Prize for Superior Achievement in Real Estate Studies: George Zhang (MArch ’21)

The Ferdinand Colloredo-Mansfeld Prize for Superior Achievement in Real Estate Studies is awarded annually to a graduating student from any program who has exhibited superior academic accomplishment and leadership in real estate studies.Druker Traveling Fellowship: Sam Naylor (MAUD ’21)

Established in 1986, The Druker Traveling Fellowship is open to all students at the GSD who demonstrate excellence in the design of urban environments. It offers students the opportunity to travel in the United States or abroad to pursue study that advances understanding of urban design.Design Studies

Dimitris Pikionis Award: Emma Lewis (MDes CC ’21)

The Dimitris Pikionis Award recognizes a student for outstanding academic performance in the Master in Design Studies degree program.The Daniel L. Schodek Award for Technology and Sustainability: Sunghwan Lim (MDes EE ’21)

The Daniel L. Schodek Award for Technology and Sustainability: Joon Haeng Lee (MDes Tech ’21)

The Daniel L. Schodek Award for Technology and Sustainability honors the memory and legacy of Professor Daniel Schodek and the standards of excellence he established during his 40 years of teaching and mentoring at the GSD. The award is given annually in recognition of the best Master in Design Studies thesis in the area of technology and sustainable design.The Design Studies Thesis Prize: Juan David Grisales (MDes ULE ’21) for “From Humboldt to Caldas: Environmental Liberations through Tropical Altitudes”

The Design Studies Thesis Prize: Proey Liao (MDes HPDM/MArch II ’21) for “An Attempt to Approach a Void: Georges Perec, Cause commune, and the Infraordinary”

The Design Studies Thesis Prize is given annually for the best thesis by a Master in Design Studies student.Outstanding Leadership in Real Estate Award: Jan Joseph Voitehovich (MDes REBE ’21)

The Outstanding Leadership in Real Estate Award offers recognition to students who exemplify academic excellence in real estate study, lead through self initiative, with generous efforts in promoting the mission of the MDes real estate program.Design Engineering

Overall Academic Performance: Sarah Christine Kovar (MDE ’21)

The Overall Academic Performance award recognizes a graduating MDE student for outstanding academic performance in the Master in Design Engineering degree program.Leadership and Community Prize: Cate Tompkins (MDE ’21)

The Leadership and Community award recognizes one or more graduating students who have displayed outstanding leadership and community building within the Design Engineering cohort and who have represented MDE values to the larger world.Outstanding Independent Design Engineering Project: Sarah Christine Kovar (MDE ’21) and Ed Bayes (MDE ’22)

The Outstanding Design Engineering Project award honors one or more graduating MDE students who have presented the Design Engineering Project that contributes, in the most compelling way, to understanding and addressing a complex societal problem.Spring 2021 All-School Welcome from Dean Sarah M. Whiting

On Tuesday, January 19, 2021 Dean Sarah M. Whiting joined the GSD community on Zoom to deliver a virtual welcome to start the spring term. A transcript of the Dean’s remarks is below. Good morning, afternoon, and evening everyone, and happy new year. I hope you all tried to have a restful holiday break. I just have to say, it’s so heartening to welcome everyone back to school for the spring semester. Many of us had been looking forward to the new year—I know I was—and I could not wait to put 2020 behind me. Twenty-twenty, though, is clearly not going away so easily. Today is January 19th, almost two weeks after the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. I’m still reeling from that day and I’m sure many of you are, too. By nature, I’m an optimistic person, but I admit I’m finding it very hard to find any silver linings right now. Yes, we have tomorrow’s inauguration to look forward to and yes, the vaccines are promising. (Speaking at a virtual conference of arts professionals over the weekend—and even dressing the part by wearing a black turtleneck—Dr. Anthony Fauci suggested that we might reach herd immunity this fall.) And yes, my surgery over break was successful, so I’m entering the new year in good health. All of these are positive, very positive, starts to the new year. But I can’t get the images of the rioters who broke into the Capitol out of my head. The vision of the confederate flag being carried within that space is particularly seared in my memory, confirming the work that this country has to do in reckoning with its structural racism, past and present. The U.S. Capitol, was designed by a succession of architects—the original competition, held in 1792, was won by Dr. William Thornton, who, according to the history on the Capitol’s website, was a “gifted amateur architect who had studied medicine but rarely practiced as a doctor.” Thornton’s original design was modified by Benjamin Henry Latrobe and Charles Bullfinch, among many others over time. Having partially burned in the war of 1812, it was rebuilt by European laborers working with American slaves. In short, this building embodies our country’s history as well as architectural history. In 1850, the building was expanded to create the House and Senate chambers—the two wings that swarmed with rioters early this month. Barton Gellman, one of my favorite columnists, described in The Atlantic what happened on January 6th as attempted “democracide.” Gellman concluded that “The republic survived a sustained attempt on its life because judges and civil servants and just enough politicians did what they had to do.” In other words, our system of checks and balances worked…just barely. Just barely because we discovered that facts, evidence, and history can be hijacked more quickly and more thoroughly than anyone could have ever imagined. We all need to be vigilant to prevent that kind of hijacking. It’s so important, so urgent, for us to pay close attention to what is happening politically, socially, economically, here in the U.S. and around the world, because yes, it does affect us. It is equally crucial for each one of us to be sure to base our research, our work, and our opinions on facts and on history that are backed up by evidence. I point you again to our event last September with Danielle Allen and Michael Murphy discussing “Our Common Purpose: Reinventing American Democracy for the 21st Century,” the report issued by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences that Allen co-authored. It’s available on the American Academy website. The report issues 31 recommendations, ranging from ranked voting to independent citizen-led redistricting in all 50 states, to subsidizing projects to reinvent the public functions that social media have displaced. While I would argue that every recommendation speaks to each of us as individuals, some, like redistricting and the ones challenging the space that social media has consumed, also speak to us as designers, planners, historians, and theorists. Susan Glasser, the New Yorker’s Washington correspondent, recently recounted that in her first job out of college working on Capitol Hill as a reporter for Roll Call Newspaper, every time she walked into the Capitol building it had awed her. The building’s solidity and its spaces inspired, utterly resonating with its civic mission. How often does someone refer to buildings that way today? Successful design (architecture, landscape, urban design, information design, product design) resonates. That doesn’t mean that it has to look like the U.S. Capitol—our world is a whole lot different from what it was in 1792. But it does mean that we have to consider the effects of what we do, and how we shape the world. Even if right now I’m challenged to find much to be optimistic about, I am unswerving in my conviction about our role. Toward that end, we have an extraordinary array of classes this semester intended to engage us in this work: courses looking at how housing has been affected by changed notions of family, changed practices of the workplace, and changed expectations about climate impact. We have courses laying the grounds for design justice. We have courses positing the impacts of neoliberalism, of material extraction, and of symbols, ranging from confederate monuments to the national park service’s monuments. We have courses covering a dizzying range of techniques, ranging from gaming technology to optical strategies to acoustic ones. We’re looking at materials: their lifespans from extraction to building units; their agency; their heterogeneities; their burning; and their symbolisms. We’re looking at Tar Creek, Oklahoma; Sao Paolo, Brazil; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; Tokyo, Japan; Harvard Square, and Nantucket Island. Despite having fewer students this semester, we have as many if not more courses than we’ve ever had. In response to feedback from students and the Innovation Task Force, we have committed this semester to capping studios to 10 people and capping seminars and limited enrollment workshops at 12 to ensure a better “Zoom world” for everyone. We have also reworked the class schedule—the Academic Affairs staff, working with the faculty, deserve a lot of thanks for this huge effort—to ensure that classes better accommodate the 14 different time zones we find ourselves teaching to. Smaller classes ensure stronger conversations—we even have a seminar devoted to that topic, “Talking Architecture,” focused on the art of the interview. Having witnessed the utter collapse of conversation and communication at the hand of those who believe that simply repeating falsehoods with greater volume or greater social media spread will somehow make them true, nothing could be more urgent right now than real conversation. I’ll be continuing my weekly office hours this semester, and I look forward to those conversations as well. To facilitate even more conversation within the school, we’ll be launching a new, internal website in the coming weeks. Called GSD NOW, this website can be understood as a digital Gund Hall, and will give everyone a direct window onto so much of the activity happening across the school at any given time. It will also include virtual “trays” that encourage formal and informal collaboration. Stay tuned for more details, but for now I can say that I’m super excited by it. GSD NOW will stay with us well past the pandemic as a source for information and collaboration within the school. And speaking of collaboration and conversation, if you weren’t tuned into the launch of Prada’s Fall Winter 2021 Menswear collection on Sunday morning, I encourage you all to go to the website. The runway show was followed by an intimate online conversation between a selection of students across the world with co-creative directors Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons. It was a remarkable acknowledgement of the value of all students, the up and coming creative generation. The GSD was represented by Celeste Martore, Ian Erikson, and Isabel Strauss. Many thanks to Assistant Professor Sean Canty for making that happen on very short notice. And as always, we have an incredible roster of lectures, conferences, and conversations in our public events calendar this term. See what happened? Just talking about what’s going on this semester has brought my optimism back. Indeed, while we have some seemingly insurmountable challenges right now, I’m really excited by what’s going on this spring—it’s all giving 2021 a good horizon. I want to end on a very personal note, though not related to me. Determined not to let 2020 go down in history as the worst year ever, Assistant Professor Jacob Reidel and his partner Laura took it upon themselves to end 2020 on a positive note. Characteristic of his talents as a writer, Jacob tells the story perfectly—you should hear it from him directly, but I’ll just share a couple lines: “Thanks to New York City’s ‘project cupid’ it became possible to meet with a clerk over Zoom. I’ll admit that jumping into a Zoom with the City Clerk on a random workday sandwiched between our own back-to-back work Zoom meetings was a whole new level of dissonance for us, but certainly special and memorable in its own way. Once we had that precious PDF license in hand, we only had until December 22 to complete the marriage with an officiant before it expired. We snuck an officiant, a laptop, and Laura’s parents into the old unused Williamsburgh Savings Bank Hall downstairs from our apartment, loaded up Zoom, exchanged rings, said our vows, smashed a glass, and got married!” I suppose that I should note here that I don’t condone breaking into spaces, but the story does continue (again, quoting Jacob): “and yes, at one point a doorman caught us using the space, but when I explained to him what we were up to, he immediately melted and said ‘let me get the lights on for you!'” A picture, a space, and a happy couple says a thousand words. Congratulations to Jacob and Laura and cheers to everyone for a light-footed and dance-filled 2021!At WW Architecture, Witte and Whiting to design new urban district for Taichung City, Taiwan

WW Architecture , the architectural practice founded by Professor in Residence of Architecture Ron Witte and Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture Sarah Whiting, has won an international competition for the design of a new urban district in Taichung City, Taiwan. The 840-hectare site is adjacent to the Taichung International Airport.

The design team is being led by Witte and includes Whiting. Additional team members include Edda Steingrimsdottir (MArch ’22), Jonathan Ng (MArch ’22), Jorge Ituarte-Arreola (MAUD ’21), Hannah Hoyt (MArch ’21), Lara Hansmann, and Ilya Rakhlin. The initial phase design team included Alia Bader (MAUD ’21), Shovan Shah (MAUD ’20), Isaac Pollan (MArch ’22), Dan Baklik (MDes REBE ’21), and Isaac Tejeira (MAUD ’22). Stoss Landscape Urbanism , led by Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture Chris Reed, is working with WW on the project.

2020 graduate Juan Reynoso bridges the worlds of public health and urban planning

Excerpted from a Harvard Gazette series of profiles showcasing some of Harvard’s stellar graduates.

Juan Reynoso is about to step into largely uncharted territory. When he graduates this spring, he’ll be only the second person to have completed a new joint Master in Public Health (MPH)/Master in Urban Planning (MUP) degree program . Launched in 2016 by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Harvard Graduate School of Design, the program allows students to pursue a transdisciplinary education in urban planning and public health and sharpen their understanding of key areas including policy, sustainability, and social determinants of health .

Over the course of the program, Reynoso has bounced between studios at GSD, where he’s wrestled with urban planning challenges, and classrooms at Harvard Chan School, where he’s learned about population health and has grown especially interested in how environmental exposures, such as air pollution or tainted drinking water, affect health.

“It’s so interesting because each graduate School at Harvard has its own culture, its own pedagogy, its own way of thinking,” Reynoso says. “This program has allowed me to break out of those silos. And that’s helped me to better make connections among a wide variety of disciplines so I can analyze how certain urban planning efforts have health co-benefits or how certain health interventions have environmental benefits.”

Pollution in the valley

Reynoso’s interest in the intersection of health and design traces back to his parents. They were born in rural Mexico and immigrated to California, living first outside of Los Angeles and later moving to the Central Valley — the inland stretch of California that’s one of the most important agricultural hubs in the world. “I was born in Tulare County, which is a pretty rural agricultural area that consistently has some of the worst air quality and water quality in the country,” he said.

As a young boy, Reynoso was oblivious to the air pollution that drifted into the valley from nearby cities and the myriad pesticides that doused the surrounding farmland and would get kicked up into the atmosphere when strong winds swept through. Looking back now, he can’t help but wonder whether the environment of Tulare County was harming him. “I was very sickly as a child,” he recalled. “I missed half of my kindergarten year because I was always ill with respiratory diseases. How is a child supposed to be successful when the environmental exposures surrounding them are making them sick?”

Reynoso’s family eventually picked up and moved to Escondido, a city in San Diego County. The difference in his health was “night and day,” he said. “Rather than miss half the school year, I’d miss like 10 days at most.”

Reynoso was an excellent student and by high school his schedule was stacked with advanced placement classes. Around the same time, a series of wildfires tore through Southern California and came unsettlingly close to Escondido. Smoke and haze lingered in the air and Reynoso started wondering what that meant for his and his community’s health. “I was taking a class in environmental science at the time, and all these things started clicking for me,” he said.

With these experiences in mind, Reynoso chose to major in human biology with a concentration in environmental health at Stanford University. After graduating, he joined The California Endowment, a statewide foundation focused on health. While there, he worked on its Building Healthy Communities initiative, exploring a wide range of issues that sat at the intersection of policy, urban planning, and health, including active transportation and community land use.

Bridging disciplines

When Reynoso began exploring graduate schools, the joint MPH/MUP program hit all the right notes. It blended his interests and fit his ambitions to improve community health through cross-disciplinary strategies.

“Juan is an energetic problem solver. As one of the first students in the joint MPH/MUP program, he has been active in helping to build a community of students. As a leader in the Healthy Places Student Group at the GSD, an area of growing student interest, Juan has been really active in organizing events and promoting dialogue,” said Ann Forsyth, Ruth and Frank Stanton Professor of Urban Planning and director of the Master in Urban Planning Program at the GSD.

Joseph Allen , assistant professor of exposure assessment science at Harvard Chan School, said it’s heartening to see students like Juan push the field of public health forward. One of the shortcomings in Allen’s own public health training, he said, was a lack of focus on building science , design, and urban planning. “Juan is working to bridge the gap between these disciplines,” Allen said. “He really is a pioneer.”

Reynoso isn’t sure what his next step will be after he graduates. But he knows that he wants to tackle some of the biggest health and environmental challenges in a way that prioritizes equity and justice. He thinks back often to his childhood in the Central Valley, and of the disparities that persist across his beloved home state. He hopes that his training at Harvard can help remedy some of these problems.

“California is the richest state in the richest country in the world, and there are millions of people who don’t have access to clean drinking water or who are constantly exposed to air pollution or who are harmed by the environment in which they live in myriad other ways,” he said. “We need to work collectively in order to solve the public health challenges of today.”

From 3D-printed face shields to strategies for a just recovery: How the Harvard Graduate School of Design community is contributing to COVID-19 response efforts

Amid the COVID-19 global pandemic, the Harvard Graduate School of Design community is working to leverage its skills and resources to contribute to response efforts. This website provides a centralized resource page for updates from across the GSD: news from the Fabrication Laboratory on production of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and other gear, relevant essays by leading design academics, remembrances of those we’ve lost, and other news from the GSD network.

News on Production of Medical Equipment

April 22, 2020: Face shield and Patient Isolation Hood (PIH) updates

The Fabrication Lab has 3D printed 948 mounts/visor and laser cut 914 shields. As materials are replenished, staff will continue making gear in collaboration with what is requested by medical personnel.

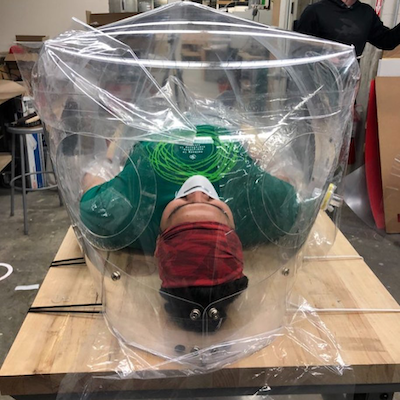

Four Patient Isolation Hood (PIH) prototypes have been completed by a team led by GSD and Harvard colleagues working in the GSD’s Fabrication Lab. Three will be delivered to Massachusetts General Hospital and one will go to Boston Children’s Hospital for review.

April 15, 2020: GSD begins patient isolation hood (PIH) design and fabrication alongside ongoing PPE efforts

The GSD’s Digital Fabrication Specialist Chris Hansen has collaborated with an array of Harvard and GSD colleagues to design two PIH prototypes, fabricating them on April 13 and delivering them to Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) on April 14. Hansen and colleagues spent much of April 15 on continued design and prototyping; by the end of this week, the GSD aims to have produced between 20 and 30 PIHs for a trial run in MGH’s intensive care unit. Read more.

April 7, 2020: GSD begins producing personal protective equipment (PPE) for Boston-area hospitals

With a stable of 3-D printers, other state-of-the-art fabrication technologies, and expert guidance from across Harvard University, the Harvard Graduate School of Design has begun production of personal protective equipment, or PPE, for front-line medical personnel at area hospitals. GSD fabrication began on April 5, and on April 6, the school delivered a first run of 90 face shields to Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and set up over one hundred 3-D printers in the school’s Gund Hall for continued production. Read more.

March 26, 2020: GSD’s Fabrication Lab facilities being considered for possible production of medical supplies

GSD Assistant Dean for Information Technology Stephen Ervin and 3-D Fabrication Specialist Chris Hansen have been in consultation with the newly formed Mass General Brigham (MGB) Center for COVID Innovation to explore whether and how the GSD’s Fabrication Lab facilities, including 3-D printers, might be put to work to address critical shortages in Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for front-line medical personnel—PPE such as face masks, and diagnostic aids such as nasopharyngeal test swabs. Together with the GSD’s Martin Bechthold, Kumagai Professor of Architectural Technology and Director of the Doctor of Design Studies and Master in Design Engineering programs, Ervin and Hansen are coordinating with other Harvard partners. Read more.

Essays from GSD Scholars

Jeffrey Schnapp on the spatial logic of quarantine: “When the world is again unparked, will it know how to unplug?”

“Being grounded has a way of regrounding people’s values and I am persuaded that shelter-in-place policies are fostering a new hyperlocalism—a rerooting in situ that is likely to continue to favor walkable and bikeable mobility over long-distance displacements.” Jeffrey Schnapp holds the Carl A. Pescosolido Chair in Italian and Comparative Literature in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and is also affiliated with the Department of Architecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Read more.

Resources for a just recovery from the GSD’s CoDesign Field Lab

“The coronavirus outbreak has both revealed and exacerbated structural inequities in American cities. Challenges faced by low- and moderate-income communities have escalated during the pandemic, with respect to housing insecurity, precarious work arrangements, lack of access to healthcare and affordable childcare, and a shortage of safe and healthy recreational spaces.” This post was written in the context of the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s project-based research seminar “CoDesign Field Lab: Program Evaluation for Change Leadership” (Spring 2020). Read more.

A radical transformation in building and designing for health is underway—but not everyone will benefit equally

GSD faculty including Malkit Shoshan, Rahul Mehrotra, Stephen Gray, Martha Schwartz, Michael Hooper, and Chris Reed examine the positive and negative implications of designing for health, particularly for marginalized and oppressed communities. Read more.

The pandemic has caused an unprecedented reckoning with digital culture. Architecture may never be the same again (and why that’s okay)

Reflections on creating architectural culture online during the pandemic, based on interviews with members of the GSD community: Jeanne Gang, Antoine Picon, Jose Luis García del Castillo y López, Michelle Chang, Ana Miljački, Lisa Haber-Thomson, and Dan Sullivan. Read more.

Pandemics and the future of urban density: Michael Hooper on hygiene, public perception and the “urban penalty”

“Prior to the pandemic, I was intrigued by the relative lack of empirical, contemporary research on the relationship between hygiene and attitudes toward density. This gap was particularly interesting because there is a substantial body of fascinating tangential evidence that suggests people’s attitudes to urban density might be influenced by hygiene concerns.” Michael Hooper is Associate Professor of Urban Planning. Read more.

How to mitigate the impact of an epidemic and prevent the spread of the next viral disease: A guide for designers

“Designers play an essential role in the prevention, control, and response of many of these diseases, so getting involved is not a matter of a choice anymore, but a duty.” Dr. Elvis Garcia is an expert in epidemics and a lecturer in the Department of Architecture. Read more.

What role do planning and design play in a pandemic? Ann Forsyth reflects on COVID-19’s impact on the future of urban life

“For the past decades, those looking at the intersections of planning, design, and public health have focused less on infectious diseases and more on chronic disease, hazards and disasters, and the vulnerable. The current pandemic brings the question of designing for infectious diseases back to the forefront and raises important questions for future research and practice.” Ann Forsyth is Ruth and Frank Stanton Professor of Urban Planning. Read more.

In Memoriam

Michael McKinnell (1935-2020); Professor and Boston City Hall architect

Michael McKinnell, a fixture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and in the architectural canon, died on March 27 at the age of 84 from COVID-19-induced pneumonia. He is survived by his wife, Stephanie Mallis (MArch ’78), and two daughters. As co-founder of Kallmann, McKinnell and Knowles, McKinnell’s built projects include Boston City Hall, Hynes Convention Center, and Harvard Law School’s Hauser Hall. At the GSD, he enjoyed a storied teaching career, joining the Department of Architecture faculty in 1966 and being named as the Nelson Robinson, Jr. Professor of Architecture in 1983, a role he held until 1988. Read more.

Michael Sorkin (1948–2020); Architect, designer, critic, pedagogue

Michael Sorkin died on March 26, 2020, at the age of 71 after contracting the coronavirus. For decades, Sorkin contributed inspiration, incisive criticism, and forward-minded design around the halls of the Harvard GSD. He studied at the GSD in the 1970s and taught there in 2002 and in 2015. He also participated in a variety of review panels and public programs over the decades, including 2015’s “Writing Architecture.” Read more.

Juan Reynoso (MUP/MPH ’20) selected as a 2019 Switzer Fellow

Juan Reynoso (MUP/MPH ’20) has been selected as a 2019 Switzer Fellow , which supports graduate students whose career goals are directed toward environmental improvement and who demonstrate leadership in the field. In addition to being awarded a $15,000 scholarship, Fellows receive leadership training and are matched with past Switzer Fellows based on professional interests.

Reynoso is pursuing Master of Urban Planning and Master of Public Health degrees through the GSD’s joint degree program with the T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Born in California’s agricultural Central Valley and a son of working-class Mexican immigrants, Reynoso has witnessed the health consequences of environmental pollution and injustice. Through his research and advocacy, he hopes to transform cities into health-promoting and sustainable places where all people have an opportunity to thrive. At the GSD, Reynoso is pursuing topics at the intersection of environmental justice, healthy cities, and climate resilience through studios and project-based courses. Prior to the GSD, he worked at the California Endowment, where he helped support organizing and advocacy campaigns to promote healthy, just, and sustainable communities in Southern California. Reynoso is a 2014 honors graduate of Stanford University.

Rosi Braidotti on collective positivity in the face of human extinction

We do not have time for entrenched antagonisms or building communities that bask in apocalyptic melancholia, says philosopher Rosi Braidotti, ahead of her lecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. If we are to survive the convergence of the fourth Industrial Revolution and the human-instigated sixth mass extinction, she argues, then both the people currently living on the margins as well as those in power must work together, locally and globally, to formulate creative solutions.

As an Italian-born, Australian-raised, Sorbonne-educated theorist who is a Distinguished Professor at Utrecht University—where she has taught since 1988—Rosi Braidotti

is herself a living manifestation of the “nomadic thought” that is at the foundation of much of her work. In numerous books, such as Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory (1994), The Posthuman (2013), and the forthcoming Posthuman Knowledge (2019), Braidotti’s nomadism objects to fixed identities and dialectical oppositions, whether man/woman, human/animal, human/technology, science/humanities, rural/urban, or secular/religious. Instead, she favors modes of thought and practice that take the form of interdisciplinarity, intersectionality, creolization, and various forms of hybridity. She argues that the latter methods—a living with rather than living against—create relationships that effect positive change rather than nurture feelings of resentment, nihilism, and collective vulnerability.

This position does not negate feminist, postcolonial, and antiracist theorists, whose valuable work Braidotti admires for illuminating the “human”—and by extension the “humanities”—as non-neutral concepts which for centuries were, and in too many ways continue to be, solely the domain of white, heterosexual, secular European men. But the urgency of the current crises—principally the twelve-year countdown towards the irreversibility of climate change and the risk that automation could make 1/3 of American workers jobless by 2013—demands unity.

“Individualism is very destructive at a time like this,” she says. “There is also a lot of resentment from women, the LGBTQ+ community, colonized people, and the descendants of slaves who say, ‘We were never considered fully human, so why should we care about this crisis?’ The focus is on [shared] pain and the affirmation of counter-identities, which is a very understandable condition that I respect and politically support. But the bulk of my work has been trying to go in a transformative direction of bridge-building. We are in this convergence together.”

In the same breath, she acknowledges that this “we” is never singular or static, and everyone could benefit from feminist and anti-racist inclusivity. Collective positivity in the face of human extinction and the destruction of the planet—neither of which are reversible through the work of a single individual—is one of Braidotti’s central concerns.

Such a project begins with what Braidotti says may be the most non-American facet of this entire discussion: the need to accept that “the self is a collective entity and not a liberal individual.” “The self is relational,” she explains. “We are never just one thing. One differs within oneself, which prevents any strong identity claims. You’re not American on Monday, black on Tuesday, straight on Wednesday, and a lesbian on Thursday. You’re all of those things. And the self is also related to the environment, society, others both human and nonhuman, and, today, to the technological apparatus and data grid that we are never really off of anymore and with which we need to interact.”

Conceiving of the self as relational as opposed to individualistic (the latter loved by capitalism for its preference for consumerism) serves as a foundation for forming new ethical structures. In this and in many other aspects of her work, Braidotti is indebted to Spinoza. “The ethical life is the pursuit of relations, situations, contexts, and values that enhance our power to act in the world. It’s about our power to take in the world’s pain and process it,” she says. In this way, she further articulates her empathy with marginalized communities but also her refusal to dwell in pain and vulnerability, because she believes these sentiments act as deterrents to transformative action and create an interminable sense of inertia.

Instead, Braidotti advocates for a neo-Spinozist praxis that turns suffering in its many forms into productive relational forces. “This ethics is a detoxing exercise in processing pain,” she says. “It’s also joyful—not in the sense of facile psychological cheerfulness but in the ability to mobilize stamina and endurance. For us, the people of the Anthropocene, that includes the strength to stare at multiple scales of challenges and say, ‘What can we do about this? Are “we” enough of a community to take this on?’ It’s a practical, hands-on approach that combines an adequate understanding of the problems [facing us] with the collectively shared energy to take them on. And why do we do it? Because we owe it to the future in a sense that we owe it to the perseverance of our own existence and that of future generations.”

Integral to this conception of ethics as a mode of living as custodians of the future is an acceptance of death that many may consider radical or even totally unfathomable. She articulates her position on death throughout The Posthuman, such as in the following passage:

“Death is not the teleological destination of life, a sort of ontological magnet that propels us forward…death is behind us. Death is the event that has always already taken place at the level of consciousness. As an individual occurrence it will come in the form of the physical extinction of the body, but as event, in the sense of the awareness of finitude, of the interrupted flow of my being-there, death has already taken place. We are all synchronized with death—death is the same thing as the time of our living, in so far as we all live on borrowed time.”

Life—which Braidotti calls “cosmic energy” and through her relation-based ontology is not confined to the physical bodies we occupy but extends in constellatory fashion to the earth, other humans and species, and technology—persists long after each of us has died. Death is not merely a point at which one’s life ends, but a condition that must be accepted before any serious and productive living can begin. “This death that pertains to a past that is forever present is not individual but impersonal,” Braidotti says. “Making friends with the impersonal necessity of death is an ethical way of installing oneself in life as a transient, slightly wounded visitor. We build our house on the crack, so to speak.”

Making friends with the impersonal necessity of death is an ethical way of installing oneself in life as a transient, slightly wounded visitor. We build our house on the crack, so to speak. In other words, only by both living as already dead and acknowledging that life will persist after we become corpses can we begin an ethical practice that is directed not at self-fulfillment but towards caring for others (both human and nonhuman), as well as those who will come after us. It is no surprise then that Braidotti also denigrates euphoric fantasies of immortality, such as those connected to Silicon Valley’s preferred notion of posthumanism as a perfect union between man and machine (consider how many science fiction films feature this conceit), as well as a booming wellness industry whose underlying ethos is an aggressive avoidance of death.

As a solution to these various psychic and social predicaments, some might demand the wholesale eradication of capitalism and technology. Braidotti, however, dismisses such clarion calls as “20th-century romanticism.” “We’re all part of the system that we call capitalism because in Spinozist philosophy, unlike in Hegel and Marx, you’re not outside the problem just because you’re against it,” she explains. “You’re against and you’re within. [Because this is the case, we must ask:] What margins can we negotiate given that none of us is going to give up our computers, mobile phones, and other things polluting the earth that are causing enormous issues as well as enormous benefits? Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s argument is that capitalism is not going to break—it’s going to bend. If it does, then let’s bring in a Spinozist ontology of immanence in which we are part of the very issue we’re trying to solve. It’s a balancing act.”

Despite the challenges facing all humans today, this position gives Braidotti hope and a conviction that creative solutions are possible. “We’re in a fantastic moment of reinvention as well as a moment of pain and mourning,” she says. “As a teacher and researcher paid by taxpayers’ money—as we are in Europe—I feel an ethical obligation to work for hope and on the construction of a ‘we’ that can take on this task and activate people to get together and [work] in the direction of joyful, gratuitous experimentations [regarding] what ‘we’ are capable of becoming.”

Photography by Sally Tsoutas

Rosi Braidotti’s lecture Posthuman Knowledge will be available in its entirety after March 12, 2019.

2018 Rouse Visiting Artist Hannah Beachler on her history-making Oscar nomination

Of the seven Oscar nominations that Marvel Studios’ blockbuster Black Panther received this year, two are historic firsts: It is the first superhero movie to contend for best picture, and Hannah Beachler , its production designer, is the first African-American ever nominated in that category. Beachler, who was a Rouse Visiting Artist at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design last fall, conceived and oversaw creation of every element of the complex environments in which the Afrofuturist feature plays out, from individual rooms to urban and natural landscapes and the now-famous fictitious African nation of Wakanda.

Since Black Panther’s release in February 2018, an estimated 170+ million people have journeyed from their theater seats to the lush and high-tech world Beachler created with her team. Black Panther was by far the greatest triumph–and test–of her career, she says. The film’s director, Ryan Coogler, with whom Beachler had worked on Fruitvale Station (2013) and Creed (2015), trusted she could deliver. But to secure the job, she had to give a live presentation of her concept to Marvel Studios. “I needed to prove to the executives and producers that I could design and manage a department of that magnitude on a tent-pole blockbuster, with the biggest film I had done at that point being Creed at approximately $35 million,” she remembers. (Black Panther had a $200 million budget.)

Her presentation was the result of two intense weeks of research, which, as she described in conversation with Jacqueline Stewart and Toni L. Griffin in 2018, forms the basis for all of her projects in “pre-pre-production.” She started with the scenes that moved her most as she read the script, storing them as “screen shots” in her mind. Those images became richer in subsequent days as she poured over literature and images, and as songs, passing scenes, or flashes of color inspired her and added texture to those mental snapshots.

For Black Panther, she started with the history of the comic, going back to the superhero’s creation in 1966 by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby all the way through to Ta-Nehisi Coates’ 2016 comic book series illustrated by Brian Stelfreeze. Knowing that the set had to reflect both African-American and African cultures, she went looking for the right African influences to incorporate—“the countries, tribes, languages, geography, economics, trade, militaries, conflicts, on and on, specifically before colonization, but also through time,” she says.

Next came Wakanda, its landscape, architecture and defining details, such as how Wakandans would use technology and interact with nature. It was a values-driven and iterative process: “I just kept creating a place where there was a sense of agency, where the people did not carry the weight of their skin color on them, where the future was their past and is their present.”

For her final presentation to Marvel, Beachler worked with illustrator Vicki Pui to develop a one-minute animatic and preliminary drawings of Golden City, capital of Wakanda. With Coogler in the room offering moral support, she won over the executives and seized the opportunity to spend a career-defining 13 months working on Black Panther. Beachler is not new to important projects or to accolades. In addition to Coogler, she has worked notably on Barry Jenkin’s Moonlight (2016), which won the Best Picture Oscar, and with director Melina Matsoukas on Beyoncé’s powerful 2016 visual concept album, Lemonade, which earned Beachler two major design awards.

I hope that diversity doesn’t just fade out as another buzzword, but that we enact the things we’ve been committed to talking about so that, soon, there will no longer be firsts. ~Hannah Beachler on her Oscar-winning production design for Black Panther

It was her final year in film school at Wright State University when Beachler decided to become a production designer. Since then, she has found her way into the work using what she calls “story design,” an approach that places the characters at the heart of creative decision making. “I always enter into the design through the people that inhabit or inhabited the spaces. For instance, on Creed it was understanding the people of Philly, the history of the city, its current state, people’s stories, accents and colloquialisms.” From there, Beachler makes the links to the design: What social, cultural, emotional and economic environment could yield these characters? And what does that environment look like in a living space? Each answer, honed in collaboration with the director, costume designers and cinematographer, brings her closer to the final set design.

Regardless of the outcome of Sunday’s Academy Awards ceremony, Beachler’s Oscar nomination is a huge endorsement of her work and another important win for diversity in the film industry courtesy of Black Panther. “The nomination means everything–it’s the highest honor you can get in the American film industry, so it’s quite humbling and breathtaking. I hope it means more opportunities are given to people of color in below-the-line positions. That diversity doesn’t just fade out as another buzzword, but that we enact the things we’ve been committed to talking about so that, soon, there will no longer be firsts.”

Photography by Chris Britt. Sketch art for Black Panther courtesy of Marvel Studios.

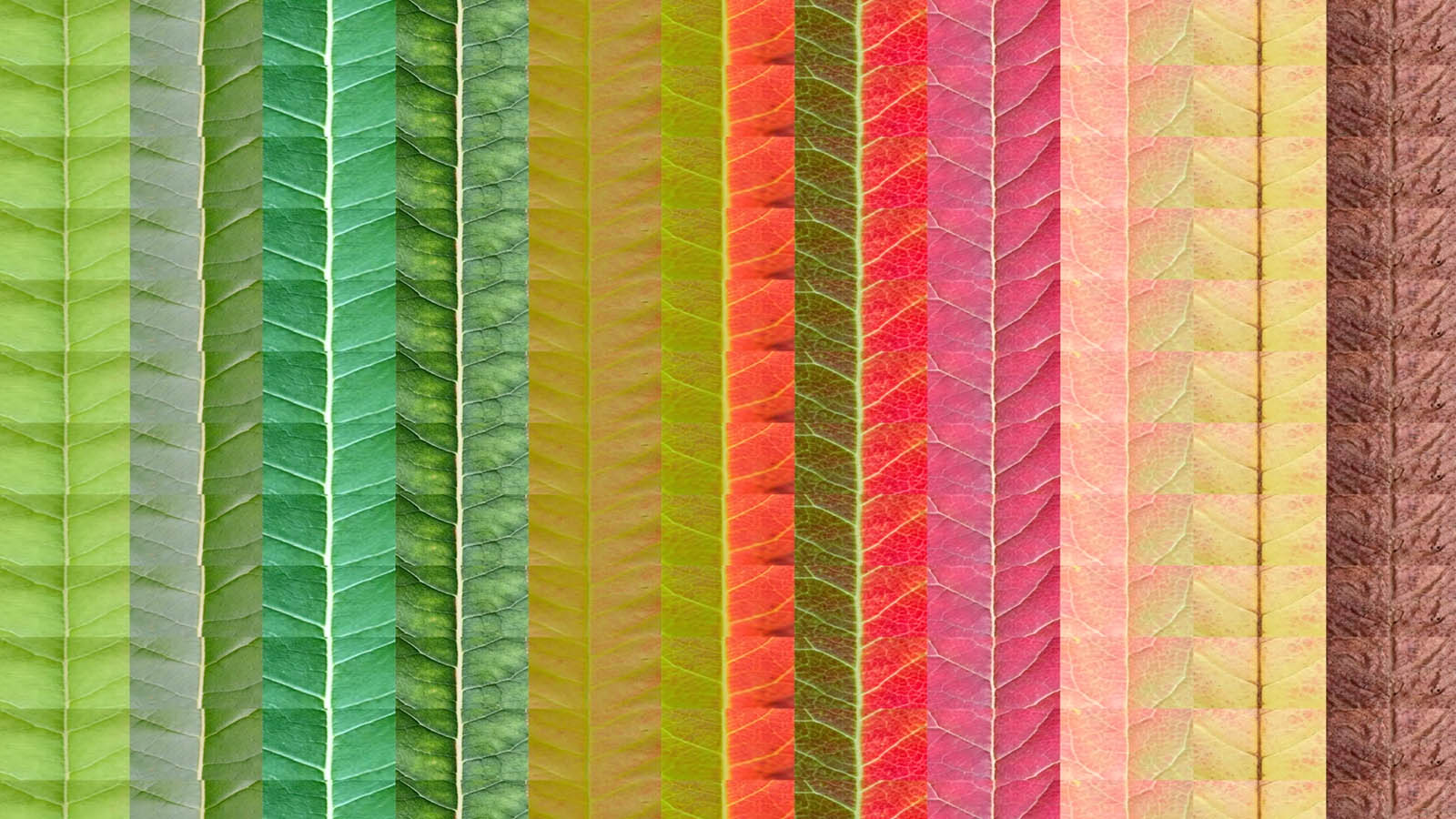

Design course opens students’ eyes to “plant blindness”

Just beyond the old iron gates of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, a creative experiment in pedagogy has been bringing the concept of plant sciences to growing, changing life.

For three years now, master’s degree candidates in Field Methods and Living Collections, led by Rosetta S. Elkin and the Arboretum’s William “Ned” Friedman, have used social theory and a methodology that examines plant evolution, morphology, built neighborhoods, and landscape design to address “plant blindness”—the human tendency to take plants for granted, reducing them to a green fuzz in the background.

“There is quite a history of human exceptionalism, and that we are the absolute species. On Maslow’s ladder [the hierarchy of needs] … plants were so low they barely made the rung. The whole class hinges on this diagnosis of plant blindness, that people assume that plants are just there, and they will always be there,” said Elkin, an associate professor of landscape architecture and faculty fellow at the Arboretum.

Yet, “We’re an entirely plant-dependent species. Plants were here way before we were; they will be here way after. They move, grow, communicate, behave, and adapt in magnificent ways and have a very different relationship with time. Once you start to appreciate that, the world around you does become a little more articulated,” she said.

Plants can be bellwethers of environmental risk, which often is overlooked by urbanists or architects focused on parcels of land whose confines are determined by economics or politics. High risk from and to the environment, such as drought, transcends manmade boundaries, however. This means that studying the effects of climate change requires acknowledging that where ecology is at risk, so is all of the area that the local environment defines, Elkin said. Continue reading at the Harvard Gazette…

Words by Deborah Blackwell & photography by Maggie Janik.