The GSD Announces 2024–2025 Faculty Promotions

The Harvard Graduate School of Design announces three faculty promotions: Michelle Chang to associate professor of architecture, Eric Höweler to professor of architecture, and Carole Voulgaris to associate professor of urban planning, effective July 1, 2024.

Michelle Chang joined the GSD as assistant professor of architecture from Rice University in 2019 and has taught architecture core studios, lecture courses on digital media, and seminars tied to her research. Two concerns recur in her syllabi: an inquiry into “vagueness” or indetermination as a counterbalance to the positivistic specificity required by many architectural design activities, and an exploration of how the conceptual structures underlying everyday design tools—especially, yet not exclusively, digital software programs—subtly inflect how design concepts translate into built forms, and how these tools’ structures inevitably affect us all. Chang researches the techniques and histories of architectural representation, investigating how optics, digital media, and modes of cultural production influence translations between design and building. In her practice, similarly, she goes beyond conventional building projects to work through ideas by curating exhibitions, creating installations that include performative elements, and producing video and sound recordings. Chang also writes in various genres, from the scholarly exposition to the evocative aphorism. Her teaching draws skillfully upon her many types of practice and is enriched by her understanding of how all aspects of the design process—including mundane and media-specific details that are often neglected—contribute to the built environment and can be engaged with creativity. She earned a Master of Architecture degree from the GSD and a Bachelor of Arts degree in International Relations (now called “International Studies”) from Johns Hopkins University, where she also completed a minor in French. This wide-ranging educational base makes her especially responsive to the concerns of architecture graduate students entering the discipline from other fields.

Eric Höweler, who first taught at the GSD in 2005 and was appointed assistant professor of architecture in 2011 and promoted to associate professor of architecture in 2017, has consistently taught foundational courses, including the Core 3 INTEGRATE studio, which guides students to integrate a building’s systems, envelope, program, and spatial concerns. This “comprehensive building” design studio plays to Höweler’s interest in creating designs that respond to many competing forces, programmatic as well as practical. Höweler completed his architectural training at Cornell University, where he earned a Bachelor of Architecture and a Master of Architecture. Along with partner Meejin Yoon, he founded Höweler + Yoon (H+Y) in 2005. He has designed buildings across a wide variety of types—housing, institutional, memorials, civic space. What underlies all of them is his focus on new material uses and an interest in forging identities that connect cultural heritage and contexts. H+Y’s recent projects include the MIT Collier Memorial, a milled granite compression structure that commemorates the life of Officer Sean Collier, who was killed in action after the Boston Marathon Bombing; the UVA Memorial, a landform structure dedicated to enslaved laborers at the University of Virginia; 212 Stuart Street, a multi-family residential tower in Boston; and the new MIT Museum in Cambridge, MA. H+Y’s work has been exhibited at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, the 2006 Design Triennial at the Cooper Hewitt in New York, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, and has been published and reviewed broadly. Additionally, Höweler and Yoon have co-authored two monographs: Verify in Field: Projects and Conversations | Höweler + Yoon (Park Books, 2021) and Expanded Practice (Princeton Architectural Press, 2009). Höweler’s receptivity to differences among audiences and users, his ability to expand on vernacular construction techniques and materials, and his generous capacity for inclusivity all respond to vital needs in today’s global professional and pedagogical practice. He looks backward, forward, and all around, to discover new ways to make buildings, generating novel and robust outcomes through his inventive use of materials, innovative building assemblies, and collaboration with non-traditional stakeholders. At a time when so many variables impact design, Höweler demonstrates the interconnectedness of issues, from tectonic and sustainable considerations to inclusive and participatory practice.

Carole Voulgaris joined the Department of Urban Planning and Design as assistant professor of urban planning in 2019. Her scholarship focuses on the use and misuse of data in transportation and travel planning, with a specialized interest in forecasting and measurement. Voulgaris has a critical perspective on how popular transportation metrics are defined and analyzed to predict the future and address, or ignore, issues of equity. Deeply skeptical about the forecasts that transportation agencies provide to funding agencies and the public, she demonstrates through specific examples how forecasts are reliably unreliable and convincingly speculates that all the incentives push toward forecasts of greater, rather than lesser, use of transportation modes. The greater the forecast of demand, the greater the ability to get the project approved and secure more funding. In this way, she extends work by other analysts, who have identified that such overestimation occurs, by examining how it happens and whether changes in programs and regulations can make a difference. Voulgaris’s prolific publication record since coming to the GSD includes articles that directly and insightfully examine the forecasting issue, including “What Is a Forecast for? Motivations for Transit Ridership Forecast Accuracy in the Federal New Starts Program,” published in 2020 in the Journal of the American Planning Association, and “Crystal Balls and Black Boxes: What Makes a Good Forecast,” published in 2019 in the Journal of Planning Literature. Voulgaris teaches transportation courses for the department, playing to her research focus, as well as teaching three courses that are part of the urban planning core curriculum, including the modules on quantitative analysis for planners and spatial analysis for planners. A testament to her teaching, Voulgaris received the 2021 Student Forum Faculty Award. Previously, she was an assistant professor of civil engineering at California Polytechnic State University where she taught courses on sustainable mobility, public transportation, transportation system planning, and intelligent transportation systems. Voulgaris holds a PhD in Urban Planning from UCLA, a Master of Business Administration from University of Notre Dame, and Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Civil Engineering from Brigham Young University.

Announcing New Faculty Appointments for the 2024–2025 Academic Year

The Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) announces eight new faculty appointments for the coming academic year. Reinforcing the existing strengths of the GSD, these new faculty members bring expertise ranging from the management of contemporary city governments to the history of ancient landscape design, and from cutting-edge robotics to sustainable construction techniques. The new faculty members effective July 1, 2024 are: Karen Lee Bar-Sinai, assistant professor of landscape architecture; Maurice Cox, Emma Bloomberg Professor in Residence of Urban Planning and Design, Iman Fayyad, assistant professor of architecture; Elisa Iturbe, assistant professor of architecture; Magda Maaoui, assistant professor of urban planning; Angela Pang, assistant professor in practice of architecture; and Kaja Tally-Schumacher, assistant professor of landscape architecture. Rachel N. Weber joins the GSD as professor of urban planning, effective January 1, 2025.

Dr. Karen Lee Bar-Sinai comes to the GSD after serving as a Marie Curie Postdoctoral Fellow and a visiting lecturer at the School of Engineering and Design at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) since 2021. A former Loeb Fellow (class of 2013), her research explores the evolving relationships between matter and technology at the intersection of landscape architecture, robotic construction, and the environment. Co-founder and design director at SAYA/Design for Change, a Jerusalem-based design studio that has drafted hypothetical solutions to brick-and-mortar problems in disputed territories around the world, she specializes in the use of design and design tools to be used in conflict resolution processes. Bar-Sinai’s recent writing includes co-authored articles “Toward Acoustic Landscapes: A Digital Design Workflow for Embedding Noise Reduction in Ground-forming” in the Journal of Digital Landscape Architecture (2023), and “Editing Landscapes: Experimental Frameworks for Territorial-Based Robotic Fabrication” in Frontiers of Architectural Research (2022). Bar-Sinai is a recipient of the British Chevening scholarship a Rothschild Fellowship, and the America-Israel Cultural Foundation (AICF) award. She earned a BArch (cum laude) from the Technion, Israel Institute of Technology; an MSc in Cities, Space and Society from the London School of Economics; and a PhD from the Technion. Bar-Sinai’s background in a succession of research and teaching venues of excellence, coupled with her commitment to innovative and rigorous research, will aid the Department of Landscape Architecture in their determination to continue to exert even greater impact in the topic of materials and design in landscape architecture. At the GSD she will advance the topic in concert with other pressing issues such as climate adaptation, the repair and recovery of landscape sites, and the shaping of landscapes for public amenity and engagement.

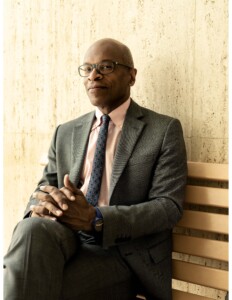

Maurice Cox’s career, spanning from private practice to academia to public service, has been dedicated to demonstrating how design excellence can be at the center of transformative urban innovation that drives social and environmental justice. An award-winning urban designer, he has been the planning and economic development director of two major cities in the United States: Detroit and Chicago. He served as mayor of Charlottesville, Virginia, held the federal appointment of Design Director for the National Endowment for the Arts under two United States presidents, and has taught at several design schools, including as a tenured faculty member at the University of Virginia and at Tulane University. At Tulane, he also served as the university’s first Associate Dean for Community Engagement, responsible for strategic initiatives between the university’s community outreach design programs of the university and city and state governmental agencies, cultural institutions, and community organizations. As director of the Albert and Tina Small Center for Collaborative Design, Tulane School of Architecture’s community design center, he operated at the intersection of design and civic engagement pursuing projects for the rebuilding of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Cox’s unique range of of experience reflects his profound and equal commitment to merging architecture, design, and politics. Upon completing a BArch from the Cooper Union in 1983, Cox moved to Italy where he practiced architecture and urban design for ten years in partnership with his wife, architect Giovanna Galfione, while also working as an assistant professor of architecture at Syracuse University in Florence, Italy. Cox’s numerous awards and accolades include, among others, the Cooper Union Presidential Medal (2004), the John Q. Hejduk Award for Architecture (2006), the Congress for New Urbanism Charter Award (2006), an honorary doctorate from the University of Detroit Mercy (2008), the Edmund N. Bacon Urban Design Award (2009), the Rudy Bruner Award for Urban Excellence (2009), an AIA Collaborative Achievement Award (2018), and the Henry Hope Reed Award (2024). Cox was a 2005 Harvard GSD Loeb Fellow, was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2023 for lifetime achievements in architecture, and recently received an Honorary Doctor of Architecture from Illinois Institute of Technology. In the Department of Urban Planning and Design at the GSD, he will help create new dialogues and pathways across our various departments and programs and help enhance our visibility at Harvard as a school addressing important challenges of our time—particularly with respect to disinvested communities, growing racial, class, and ethnic inequality, and the positive role that design excellence in the urban built environment can play in meeting these challenges. Additionally, as the Emma Bloomberg Professor in Residence of Urban Planning and Design, Cox will play an integral role in connecting the school to cities around the world.

Iman Fayyad rejoins the GSD from Syracuse University, where she served as assistant professor of architecture, coordinating the first-year design studio curriculum and overseeing a research lab in spatial geometry with a focus on tectonics, construction, and representation. Fayyad is founding director of project:if, an award-winning research practice that explores the relationship between architectural geometry and material economy, sensory perception, and the politics of physical space and building practice. Her public work and research on zero-waste geometric construction techniques has been funded by grants through the MetLife Foundation and the Lender Center for Social Justice, and has received recognition by the Architect’s Newspaper Best of Design Young Architects Prize, the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) Faculty Design Award, and Architizer‘s Architecture For Good Award. She has published in Technology | Architecture and Design, Nexus Network Journal: Architecture and Mathematics, Log, Pidgin, Archinect, Advancements in Architectural Geometry, the New York Times, and has exhibited at the Yale Architecture Gallery, Carnegie Museum of Art, citygroupNY, and the Roca London Gallery. She is a 2024 MacDowell Colony Fellow. Fayyad holds a Bachelor of Science in Architecture from MIT and a Master of Architecture with Distinction from the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where she was the recipient of the AIA Certificate of Merit, Faculty Design Award, and the Araldo A. Cossutta Prize for Design Excellence. Prior to Syracuse, Fayyad served on the faculty at the GSD, MIT, and Princeton, and was the inaugural John Irving Innovation Fellow at Harvard. She has practiced in offices in Boston, New York, and Paris. As a leading voice in articulating the significance of geometry as an underlying force in spatial discourse, Fayyad will advance the knowledge of the disciplinary interrelationships between geometry and architecture, including fundamental issues of structure, tectonics, materiality, and climate resilience.

Elisa Iturbe, who earned dual master’s degrees from the Yale School of the Environment and the Yale School of Architecture, joins the Department of Architecture as assistant professor of architecture. Previously, Iturbe served as assistant professor at the Cooper Union; she has also taught at the Yale School of Architecture and Cornell AAP. Additionally, Iturbe is co-founder of Outside Development, a design and research practice. Through her work, Iturbe interrogates the relationship between energy, power, and form, working across theory and design to lay bare the allegiance between architecture and carbon modernity. Her research and practice offer an alternative history of architecture’s role in the climate crisis, linking the adoption of fossil fuels to the emergence of specific spatial and formal concepts—most of which are still taught and used, leaving the fundamental tenets of carbon modernity fully intact, despite contemporary improvements in building technology. Recently, she co-curated and co-produced the exhibition Confronting Carbon Form at the Cooper Union, which exhibited original works in various media that define the spatial concepts of the carbon age. In tandem, she curated a year-long lecture series titled “Architectures of Transition” and a symposium titled “Order!: The Spatial Ideologies of Carbon Modernity.” This work builds on Iturbe’s guest-edited issue of Log, titled “Overcoming Carbon Form,” published in 2019. Her writings have been published in AA Files, Log, Perspecta, e-flux, and the New York Review of Architecture, and she co-authored, with Peter Eisenman, Lateness (Princeton University Press, 2020). Because the subjects of spatial thinking and climate change are often disconnected, Iturbe offers a unique voice that interrogates how architecture, space, and form participate in processes of epochal change.

Dr. Magda Maaoui recently served as a GSD design critic in urban planning and design and as a postdoctoral researcher at the Joint Center for Housing Studies. Maaoui’s research has been used in campaigns for good governance, affordable housing provision, and public and environmental health reform in France and in the United States. Her work has been featured in popular news sources including Le Monde, Architectural Review, Ouest France, Bondy Blog, La Gazette des Communes, and France Inter and France Culture public radio. While her research emphasizes housing policy and real estate development, she also studies related issues of healthy urban planning, neighborhood and community development, sustainability, planning regulation, and planning research methods. A member of the American Planning Association, the Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning and the Urban Affairs Association, and a reviewer for the Revue Urbanités, Maaoui maintains an active stream of collaborative research, thanks to the support of institutions like the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and the Albertine Foundation. She has written or co-written peer-reviewed articles for the Journal of Planning Education and Research, Housing Studies, Urban Studies, and the Berkeley Planning Journal, and contributed to the books Pour en finir avec le petit Paris (2024), Habiter l’indépendance (2022) and Zoning: A Guide for 21st-Century Planning (2020). Maaoui co-founded the participatory design practice Ateliers d’Alger, a collective focusing on urban planning solutions for neighborhoods in Algeria and in France based on local participatory workshops, civic engagement, and the curation of expertise from local and transnational professionals. Ateliers d’Alger has received awards and grants from the Mairie de Paris, the Davis Foundation, and the Ford Foundation. She has a PhD from Columbia University, a master’s degree in Geography and Planning from École Normale Supérieure de Lyon, and bachelor’s degrees in Planning and Geography, and English Literature and Civilization from École Normale Supérieure de Lyon and Universités Lyon 2 and 3. She has been an urban planning research associate at the Atelier Parisien d’Urbanisme (APUR) in the Paris Mayor’s Office, and acted as an external expert consultant for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) working in Morocco. A former Fulbright Fellow and Normalienne Agrégée civil servant, Maaoui has been an adjunct professor at the University of Paris Cité and the University of Paris-Cergy and was a visiting scholar at UC Berkeley during her master’s training. Her ability to link theory to practice, extensive knowledge of multiple planning systems, and commitment to good governance will bolster the Department of Urban Planning and Design.

Angela Pang, recent GSD design critic in architecture and the founder of PangArchitect, will join the faculty as assistant professor in practice of architecture. Guided by site and program with the integration of tectonics and structure, she challenges conventions through design and research, always balancing intellectual scrutiny and pragmatic solutions. Her firm’s recent design work includes the completion of several university libraries in Hong Kong, including the Polytechnic University, the Lingnan University, and the Chinese University. Other recent works include the Hong Kong Literature Archive and Research Center, as well as a student dormitory at the New Asia College for 300 students, both at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The firm’s major research projects include a research consultancy on building program for M+, a museum of contemporary visual culture in Hong Kong, and a series of exhibitions on Shinohara Kazuo, funded by the Graham Foundation and the Japan Foundation, done in collaboration with Washington University in St. Louis, the Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zürich, and the GSD. PangArchitect has received numerous design awards including the Architect’s Newspaper Award for Best Library Design, the Green Building Award from the Hong Kong Green Building Council, APIDA Top 10 Public Space in Asia Pacific, the FuturArc Green Leadership Award, the HKIA Cross-Strait Architectural Design Award, and multiple recognitions from Dezeen Design Award, the World Architecture Festival Award, and the Hong Kong Institute of Architects. Before establishing PangArchitect in 2010, Pang worked for Rafael Moneo in Madrid and SANAA in Tokyo. She received a MArch II from the GSD and a BArch from Cornell University. The Department of Architecture will be further enriched by her remarkable success in practice and extensive experience in building integration, from concept to execution.

Dr. Kaja Tally-Schumacher joins us as an assistant professor in landscape architecture with a focus on environmental history. She was previously a visiting scholar in Cornell’s Institute of Material Studies and Archaeology, a faculty associate in the Institute for European Studies at Cornell’s Einaudi Center, and assistant director of the Casa della Regina Carolina Excavation, Pompeii (Cornell-Bologna). Trained as a historian of ancient landscape architecture, her primary area of expertise is the archaeology and analysis of designed landscapes and environments in the Roman world (ca. 2nd century BCE to 4th century CE) across Western Eurasia and Northern Africa. Most recently she has been awarded the Ellen and Charles Steinmetz Endowment for Archaeology from the Archaeological Institute of America for her work on the gardens at Pompeii, a prestigious early-career award within the field of Classical Archaeology. Placing equal emphasis on previously unrecognized makers of landscape and minute investigation of artifactual, literary, and paleo-topographical evidence, Tally-Schumacher’s research advances a conceptually challenging and meticulously documented approach to the history of landscape architecture as co-produced by social, material, and climactic factors. Tally-Schumacher’s first book project, Gardeners, Plants, and Soils of the Roman World, draws an ambitious but finely detailed transect from antiquity to the Early Modern and Antebellum periods. Tally-Schumacher has a B.A. from the University of Minnesota with a double major in Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology and Political Science and she earned an MA with distinction from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, with a major in Roman art with a minor in nineteenth- and twentieth-century architecture. She earned her PhD in Ancient Art and Archaeology from Cornell University in 2020. At Cornell she was runner-up award for the James F. Slevin Assignment Sequence Award (2017), granted for designing an innovative sequence of assignments in her course on Ancient Pompeii; promoting foundational, transferable skills; and actively addressing different learning styles. Tally-Schumacher’s approach to history presents several exciting paths forward for the department of landscape architecture, in addition to making new connections between and across diverse questions and fields of inquiry which are not typically seen to be connected.

Dr. Rachel N. Weber will be joining us in January 2025 from the University of Illinois at Chicago where she has taught and conducted research in the fields of economic development, real estate, city politics, and public finance since 1998. Weber is best known for her pioneering work unearthing how municipal government engagement with financial markets significantly affects the way cities operate and develop. She is the author of over 50 peer-reviewed journal articles, as well as numerous book chapters and published reports, and is the co-editor of the Oxford Handbook of Urban Planning, a compilation of 40 essays by leading urban scholars. Her latest book, From Boom to Bubble: How Finance Built the New Chicago, won the Best Book Award from the Urban Affairs Association in 2017. Weber’s current research project spotlights the predictive knowledge practices that allow real estate investors to create and extract value from the built environment. Titled “The Urban Oracular: Speculating on the Future City,” this work builds on her previous insight that those involved in urban development too often are overconfident in their forecasts about supply and demand. Focusing on the period from the Global Financial Crisis through the Covid-19 pandemic, Weber is examining the role of ever more sophisticated models and algorithms that enable investors to convert the future into capital. This work holds the promise of extending beyond urban development to the very nature of planning itself, which necessarily relies on projective techniques that themselves are routinely applied yet often understudied. In addition to her academic responsibilities, Weber has served as an advisor to planning agencies, political candidates, and community organizations on issues related to financial incentives, property taxes, and neighborhood change. She was appointed to then-presidential candidate Barack Obama’s Urban Policy Committee in 2008 and by Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel to the Tax Increment Financing Reform Task Force in 2011. She has been cited and quoted extensively in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, National Public Radio, The Economist, Crain’s, the Chicago Tribune, and other news outlets. She holds a master’s and PhD in City and Regional Planning from Cornell University and an undergraduate degree in Development Studies from Brown University. We are thrilled to welcome her to the Department of Urban Planning and Design and to the GSD.

Thandi Loewenson Awarded 2024 Wheelwright Prize

Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD) is pleased to name Thandi Loewenson the winner of the 2024 Wheelwright Prize . The $100,000 grant supports investigative approaches to contemporary architecture, with an emphasis on globally minded research.

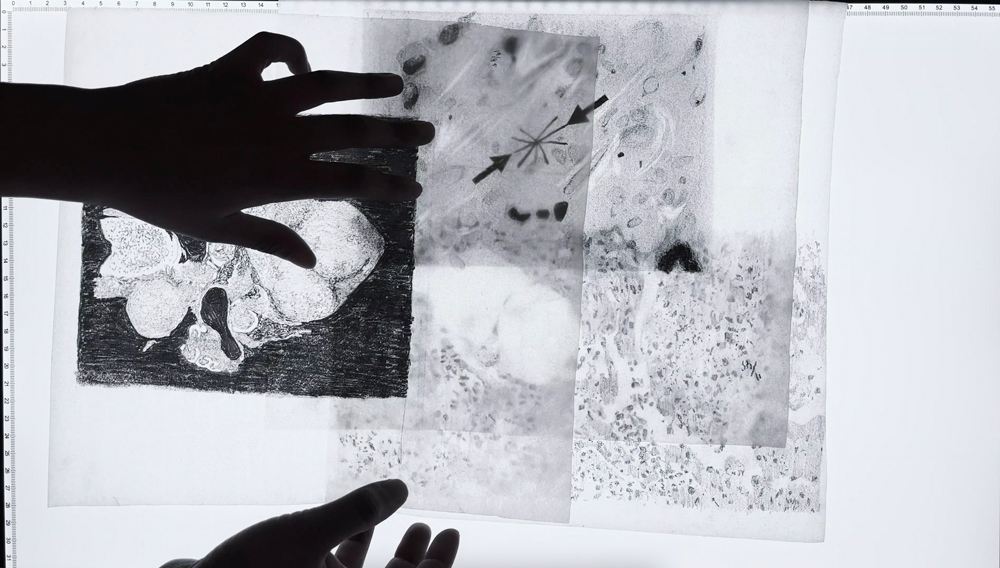

Loewenson’s project, Black Papers: Beyond the Politics of Land, Towards African Policies of Earth & Air, engages a dynamic terrain of social and spatial relations in contemporary Africa. Whereas the importance of land in the context of African liberation movements and subsequent postcolonial governments has been analyzed mainly in terms of private property, dispossession and redistribution, and agriculture and mining, Loewenson pushes our understanding in radically new directions with the introduction of an analytic framework she calls “the entanglement of Earth and Air.” Through this framework, Loewenson expands these interpretations of land to include many overlapping terrains above and below ground, spanning rare metals buried far below the Earth’s crust and reaching up to the digital cloud and Earth’s ionosphere, and ranging in scale from a solitary breath of air to entire weather systems.

Ultimately, Loewenson’s project will examine how colonial capitalist systems of racialization, dispossession, and exploitation are co-constituted and endure across multiple, entangled Earthly and airborne terrains. The Wheelwright Prize will support her study, which will include aerial techniques for surveying and prospecting, as well as the mining of “technology metal,” minerals employed in networked devices that also underwrite a global system of digital dispossession. Among the forms her findings will take are the Black Papers, studies that aim to shape both policy discourse and public perception. Incorporating drawings, moving image, and performances as well as critical creative writing, the Black Papers are designed to reach broad audiences through popular media including video, radio, and social platforms like WhatsApp.

“The question of land, and its indelible link to African liberation and being, echoes across the continent as a central theme of liberation movements and the postcolonial governments that followed. Instead of solely engaging land as a site of struggle, this work situates land within a network of interconnected spaces, from layers deep within the Earth to its outermost atmospheric reaches,” says Loewenson. “This research presents a radical shift: developing a new epistemic framework and a series of open-access, creatively reimagined policy proposals—the Black Papers—in which earth and air are not distinct, but rather concomitant terrains through which racialization and exploitation are forged on the continent, and through which they will be fought. The Wheelwright Prize is uniquely placed to support such ambitious inquiry, enabling me to bring together seemingly disparate yet closely bound parts of our planet, and agitate for a more just and flourishing world.”

The Wheelwright Prize will fund two years of Loewenson’s research and travel. She plans to focus her work in seven African nations: the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Kenya, Senegal, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

“Expanding what constitutes architectural research, Thandi defines a sectional slice of inquiry that spans from the subterranean to the celestial. Her project is nothing short of a full reconceptualization of land and sky as material realities, sources of value, and sites of political struggle,” says Sarah M. Whiting, Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture at the GSD. “Such vision exemplifies the kind of ambition the Wheelwright Prize is meant to support. Along with the rest of the jury, I could not be more thrilled that she is this year’s winner.”

In addition to Whiting, jurors for the 2024 prize include: Chris Cornelius, professor and chair of the Department of Architecture at the University of New Mexico School of Architecture and Planning; K. Michael Hays, Eliot Noyes Professor of Architectural Theory and co-director of the Master in Design Studies program at the GSD; Jennifer Newsom, co-founder of Dream the Combine and assistant professor at Cornell University’s College of Architecture, Art, and Planning; John Peterson, curator of the Loeb Fellowship at the GSD; and Noura Al Sayeh, head of Architectural Affairs for the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities.

“Loewenson’s research examines our planetary section, reaching from the probative violence of mining and extractive terrains to the fog of particles in the air we breathe and the digital fragments ricocheting in our outer atmosphere. Building from a necessary set of scholarly research about the entanglements of earth, air, bodies, and dispossession (on multiple timescales), her work extends these arguments into a material practice rich with layers—the matter that matters to our time,” says Newsom. “Loewenson promises to think with the materiality of place, collapsing the spaces of poetics and the landscapes of policy with the literal terrain of the context these projections shape. Her proposal was clear-headed about its purpose, research methods, and outputs, yet remained nimbly open to the propulsive capacity for her work to fractal outward in ‘activist academic practice’—to new audiences, interlocutors, policymakers, students, and neighbors. Loewenson constructs a relational field of inquiry essential for our discipline.”

The Wheelwright Prize supports innovative design research, crossing both cultural and architectural boundaries. Winning research proposal topics in recent years have included the environmental and social impacts of sand mining; the potential of seaweed, shellfish, and the intertidal zone to advance architectural knowledge; and new paradigms for digital infrastructure.

Loewenson was among four distinguished finalists selected from a highly competitive and international pool of applicants. The 2024 Wheelwright Prize jury commends finalists Meriem Chabani, Nathan Friedman, and Ryan Roark for their promising research proposals and presentations.

Born in Harare, Loewenson is an architectural designer/researcher who mobilizes design, fiction, and performance to stoke embers of emancipatory political thought and fires of collective action, and to feel for the contours of other, possible worlds. Using fiction as a design tool and tactic, and operating in the overlapping realms of the weird, the tender, the earthly, and the airborne, Loewenson engages in projects which provoke questioning of the status-quo, whilst working with communities, policy makers, unions, artists, and architects to act on those provocations. A senior tutor at the Royal College of Art, she holds a PhD in Architectural Design from The Bartlett, UCL. Loewenson is a co-founder of the architectural collective BREAK//LINE —an “act of creative solidarity” that “resists definition with intent”—formed at The Bartlett in 2018 to oppose the trespass of capital, the indifference towards inequality, and the myriad frontiers of oppression present in architectural education and practice today. She is also a contributor to EQUINET , the Regional Network on Equity in Health in East and Southern Africa, a co-founder of the Fiction, Feeling, Frame research collective at the Royal College of Art, and a co-curator, with Huda Tayob and Suzi Hall, of the open-access curriculum project Race, Space & Architecture.

Summer Reading 2024: Design Books by GSD Faculty and Alumni

Building your summer reading list? This selection of recent publications by Harvard Graduate School of Design faculty and alumni—organized alphabetically by title—includes design-related topics from wildfires to the Tower of Babel.

In Absolute Beginners (Park Books, 2022) Iñaki Ábalos, design critic in architecture, addresses innovation in architecture, examining the ways in which architectural creation, like philosophical thought, intertwines with reflections on the past and appropriations of recurring challenges.

Approaching Architecture: Three Fields, One Discipline (Routledge/Taylor & Francis, 2023) interrogates the relationship of research, pedagogy, and professional practice. Edited by Miguel Guitart (MArch ’03), the book collects 18 contributions from around the globe that challenge the discipline’s compartmentalization. One reviewer characterizes the compilation as “a thoughtful and engaging set of arguments, provocations, and reflections that work collaboratively, curiously, and critically to help reconsider the necessary entanglements of architecture’s ‘three fields.’”

In Architecture After God: Babel Resurgent (Birkhäuser, 2023), Kyle Dugdale (MArch ’02) explores the Tower of Babel as a concept aligning architecture and morality from ancient Babylon to twentieth century Europe, where early modernism’s idealism collided with the rising nationalism that prefigured World War II. “Dealing in structural metaphor, utopian aspiration, and geopolitical ambition, the book’s narrative”—in the words of the publisher—”exposes the inexorable architectural implications of the event described by Nietzsche as the death of God.”

Architecture and Micropolitics: Four Buildings 2011-2022 (Park Books, 2022), by professor in practice of architecture Farshid Moussavi (MArch ’91), investigates the relationship between architecture and society, using Moussavi’s work to highlight the architect’s enduring relevance and demonstrate how buildings can be grounded in the micropolitics of everyday life. The book includes essays by GSD design critic in architecture Iñaki Ábalos and others.

Architectures of Transition: Emergent Practices in South Asia (Edicions Altrim S.L., 2023), written by John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization Rahul Mehrotra, Devashree Shah (MArch II ’23), and Pranav Thole (MArch ’23), draws on a conferences series that took place from March 2022 to March 2023. The publication foregrounds conversations around architecture and evolving models of practice in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives.

Armadillo House: A Conversation between Marc Camille Chaimowicz and Roger Diener (Walther König, 2023), edited by Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen—John Portman Design Critics in Architecture—with Cristina Bechtler, presents a discussion between artist Chaimowicz and architect Diener covering their collaboration on The Armadillo House in Basel, Switzerland. The book details their respective artistic visions and differing approaches to spatial arrangements.

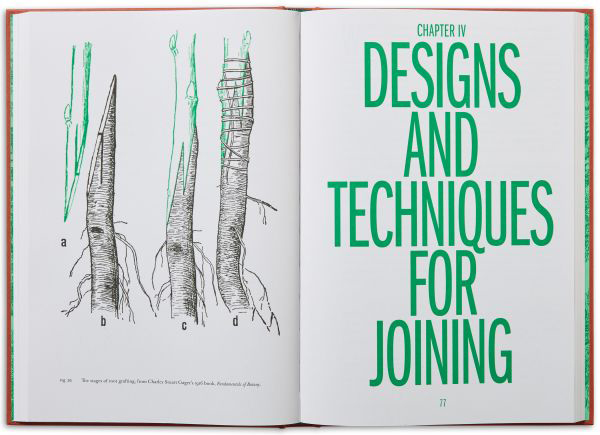

The established horticultural practice of grafting connects two living plants, one old and one new, to grow and thrive as one. In The Art of Architectural Grafting (Park Books, 2024), professor in practice of architecture Jeanne Gang (MArch ’93) applies the notion of grafting to existing buildings and urban lands as a paradigm for rethinking adaptive reuse and addressing climate change. Through theoretical essays and architectural examples, Gang explicates the concept of architectural grafting, urging her peers to “renew our role as cultural leaders who envision and create a different future” by “add[ing] capacity to what already exists, caring for the old and simultaneously making original contributions to it.”

In Atlas of the Senseable City (Yale University Press, 2023), Antoine Picon, G. Ware Travelstead Professor of the History of Architecture and Technology, and Carlo Ratti explore how sensing technologies associated with digital mapping impact everyday life. Ubiquitous sensors offer new ways to visualize cities with implications that touch on many areas, from making municipalities more efficient to assisting in the support of vulnerable urban populations.

Edited by Michael Van Valkenburgh—Charles Eliot Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture, Emeritus—and Elijah Chilton, Brooklyn Bridge Park: Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (Monacelli, 2024) chronicles the transformation of 85 acres of Brooklyn’s post-industrial landscape into a waterfront park that stretches 1.3 miles along the East River. This book explores the firm’s efforts, over 23 years, to convert parking lots and derelict piers into a public recreational space and living ecosystem.

For a century, Zurich—a center of global finance and Switzerland’s largest city—has embraced, within its for-profit real estate market, a cooperative model that supports nonprofit housing. Cooperative Conditions: A Primer of Architecture, Finance, and Regulation in Zurich (gta Verlag, 2024), edited by design critic in urban planning and design Susanne Schindler with Anne Kockelkorn and Rebekka Hirschberg, examines the interplay between housing’s architectural, regulatory, and fiscal instruments, rendering aspects of Zurich’s cooperative model applicable for other locations.

Design by Fire: Resistance, Co-Creation, and Retreat in the Pyrocene (Routledge, 2023) by Emily Schlickman (MLA ’12) and Brett Milligan addresses our relationship with, and vulnerability to, wildfires. Nearly thirty case studies categorized into three approaches—resisting, embracing, and retreating—offer possible design strategies for building in fire-prone landscapes. One reviewer described Design by Fire as “the essential guidebook and atlas for the pyro-future that is already here,” offering “a foundation for understanding—and living in—the world to come.”

With Design Thinking and Storytelling in Architecture (Birkhäuser, 2024) Peter Rowe—Raymond Garbe Professor of Architecture and Urban Design and Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor—and Yoeun Chung (MAUD ’19, DDes ’22) explore design thinking, posited as “a fundamentally different way of knowing the world and a particular form of addressing creative problems.” The authors assert that designing rests on underlying principles of inquiry, and storytelling is preceded by a process involving empathy or careful listening. The book illustrates examples of testing and prototyping that generate a deeper understanding of architecture.

Flowcharting: From Abstractionism to Algorithmics in Art and Architecture (gta Verlag, 2023) by Matthew Allen (MArch ’10) investigates mid-twentieth-century experimentation that harnessed serial effects to create art and architecture. As Allen writes, “by adopting flowcharting procedures from scientific management, [the avant-garde] enacted a paradigm shift that had long been a cherished dream of modernism, replacing composition with organization as the basis of design.”

Design critic in architecture Andrew Heid penned the introduction to Glass Houses (Phaidon Press, 2023), a lavishly illustrated publication presenting 50 homes, dating from the early modern era through today, built almost entirely from glass. Featured architects include Tatiana Bilbao, Lina Bo Bardi, Ofis Architekti, Herzog & de Meuron, Hiroshi Nakamura, Kazuyo Sejima, Philip Johnson, Mecanoo, John Lautner, Richard Rogers, and Mies van der Rohe.

Lina Ghotmeh, Kenzo Tange Design Critic in Architecture, worked closely with editors Alexa Chow and Natalia Grabowska to document her firm’s pavilion at the Serpentine Galleries in Kensington Gardens, London. Titled Lina Ghotmeh – Architecture – À Table!: Serpentine Pavilion 2023 (Walther König, 2023), the catalog contains illustrations and contributed essays, as well as a lengthy interview with Ghotmeh conducted by renowned critic and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist.

In The Multiplex Typology: Living in Kuwait’s Hybrid Houses (DOM Publishers, 2022) authors Joaquín Pérez-Goicoechea (MArch ’02), Sharifa Alshalfan, and Sarah Alfraih issue a call for alternative approaches to housing that are rooted in cultural specificity and adaptability. They focus on the multiplex—a ubiquitous yet officially unacknowledged form of multi-family housing that hides behind the facades of the single-family villa—arguing that this unique type offers a viable option for contemporary housing development in Kuwait.

Sarah Oppenheimer: Sensitive Machine (DelMonico Books/Wellin Museum of Art, 2023), edited by Tracy L. Adler, details four interactive artworks created by Sarah Oppenheimer, design critic in architecture, for the Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College. As Adler notes, “Oppenheimer’s work challenges us to consider how interactions with the built environment shape not just those who occupy a particular space, but how their presence impacts the space itself: how we fill and move through a space, how we adapt a space to our needs even when we are subject to its limitations.”

In Silt Sand Slurry: Dredging, Sediment, and the Worlds We are Making (AR+D, 2023), Gena Wirth (MLA ’09, MUP ’09), Rob Holmes, and Brett Milligan explore sediment’s role in shaping and facilitating modern life. As the book’s description notes, “Anthropogenic action now moves more sediment annually than ‘natural’ geological processes—yet this global reshaping of the earth’s surface is rarely discussed and poorly understood.” The authors outline an adaptive approach to designing with sediment as opposed to continuing current management practices, which often negatively impact larger ecological and human systems.

John Portman Design Critics in Architecture Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen edited Sylvie Fleury: Double Positive (Jrp Ringier Kunstverlag Ag, 2022) to accompany an exhibition on the artist’s work that ran from October 2022 through March 2023 at the Bechtler Stiftung in Zurich. The book offers new insight into Fleury’s 1990s fashion collection, which the artist arranged as intentional mises-en-scène concerning consumerism and fetishization.

Segregation and Resistance in the Landscapes of the Americas (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2023) draws on a 2020 Dumbarton Oaks symposium, assembling essays on the histories of segregation and resistance. Edited by Eric Avila and Thaïsa Way, lecturer in landscape architecture and director of Garden and Landscape Studies at Dumbarton Oaks, this collection considers how cultural and spatial practices of separation, identity, response, and revolt are shaped by place and inform practices of place-making.

Sharing Tokyo: Artifice and the Social World (Actar, 2023) collects essays and drawings focused on the theme of sharing Toyko’s urban space. Co-edited by Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design and Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor Mohsen Mostafavi and Kayoko Ota, the book offers insights, new perspectives, and speculative experiments in Tokyo’s urbanism and architecture that can be transferred to other contexts.

Technical lands, spaces united by their “exceptional” status, range from demilitarized and disaster exclusion zones to prison yards, industrial extraction sites, and airports. Edited by Charles Waldheim, John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture, and Jeffrey S. Nesbit (DDes ’20), Technical Lands: A Critical Primer (JOVIS, 2022) assembles writings representing diverse disciplines, geographies, and epistemologies to illuminate the meaning, political implications, and increasing significance of these spaces.

In Thinking and Building on Shaky Ground (Birkhäuser, 2023), Yun Fu (MArch I AP ’15, DDes ’20), design critic in urban planning and design, explores strategies for earthquake-resilient architecture. Marrying technical knowledge with social and cultural understanding, these approaches allow for the development of contextual solutions applicable to all scales, from furniture to urban plans.

Urban Natures: A Technical and Social History, 1600-2023 (Pavillon de l’Arsenal, 2024), by G. Ware Travelstead Professor of the History of Architecture and Technology Antoine Picon, examines the history of nature’s place in cities through the lenses of urban planning, public health, food systems, and aesthetics. The publication accompanies an exhibition at Paris’s Pavillon de l’Arsenal mounted from April through September 2024.

Vincent Scully: Architecture, Urbanism, and a Life in Search of Community (Bloomsbury, 2023) by A. Krista Sykes (PhD ’04) details the life, career, and legacy of the architectural historian and critic Vincent Scully (1920–2017). Emerging in the 1950s as a guiding voice in American architecture, Scully investigated topics ranging from ancient Greek temples and Pueblos of the American Southwest to the work of Robert Venturi, Aldo Rossi, and New Urbanism. Scully believed that architecture shapes and is shaped by society, and that the best architecture responds to the human need for community and connection.

The GSD Announces Finalists for the 2024 Wheelwright Prize

Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD) is pleased to announce four shortlisted architects for the 2024 Wheelwright Prize: Meriem Chabani, Nathan Friedman, Thandi Loewenson, and Ryan Roark. The Wheelwright Prize is an international competition for early-career architects.

Winners receive a $100,000 fellowship to foster innovative architectural research that is informed by cross-cultural engagement and can make a significant impact on architectural discourse. Winning research proposal topics in recent years have included the environmental and social impacts of sand mining; the potential of seaweed, shellfish, and the intertidal zone to advance architectural knowledge; and new paradigms for digital infrastructure.

The 2024 Wheelwright Prize drew a wide pool of international applicants. A winner will be announced later in June.

Jurors for the 2024 prize include: Chris Cornelius professor and chair of the Department of Architecture at the University of New Mexico School of Architecture and Planning; K. Michael Hays, Eliot Noyes Professor of Architectural Theory and co-director of the Master in Design Studies program at the GSD; Jennifer Newsom, co-founder of Dream the Combine and assistant professor at Cornell University’s College of Architecture, Art, and Planning; John Peterson, Curator of the Loeb Fellowship at Harvard GSD; Noura Al-Sayeh, Head of Architectural Affairs for the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities; and Sarah M. Whiting, Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture at Harvard GSD.

The shortlisted architects are:

Meriem Chabani

Algeria-born, Paris-based Chabani is the founder and principal of NEW SOUTH

, an award-winning architecture, urban planning, and anthropology practice prioritizing spaces for vulnerable bodies in contested territories. Her work on complex sites includes the Taungdwingyi cultural center in Myanmar, the Globe Aroma refugee art center in Brussels, and the upcoming Mosque Zero in Paris. She currently teaches at ENSA Paris Malaquais and the Royal College of Arts. In 2020 Chabani won the Europe 40 under 40 award. She is a recipient of the Graham Foundation Grant and was named one of the leading young female architects in France by AMC in 2023.

Chabani’s proposal is titled “On Sacred Grounds: Sanctuaries in the Secularocene.”

Nathan Friedman

Friedman is co-founder of the Mexico City–based design office Departamento del Distrito

and a Professor in the Practice at the Rice University School of Architecture. His office was an official contributor to the 2021 Chicago Architecture Biennial and received the 2022 Architectural League of New York Prize, recognized for a diverse body of work that operates at the intersection of politics, identity, and the built environment. Friedman holds an MS from the Department of History, Theory, and Criticism of Architecture and Art at MIT and a BArch from Cornell University.

Friedman’s project is titled “Sovereign Systems: Resource Management in Latin America.”

Thandi Loewenson

Born in Harare, Loewenson

is an architectural designer/researcher who mobilizes design, fiction, and performance to stoke embers of emancipatory political thought and fires of collective action, and to feel for the contours of other, possible worlds. Using fiction as a design tool and tactic, and operating in the overlapping realms of the weird, the tender, the earthly and the airborne, Loewenson engages in projects which provoke questioning of the status-quo, whilst working with communities, policy makers, unions, artists and architects to act on those provocations.

Loewenson’s proposal is titled “Black Papers: Beyond the Politics of Land, Towards African Policies of Earth & Air.”

Ryan Roark

Roark

, PhD, AIA, is an architect, writer, biochemist, and Assistant Professor of Architecture at IIT in Chicago, where her research focuses on radical adaptive reuse and its role in urban development. At IIT, she directs the second-year undergraduate studio, on housing, and runs a lab where she develops novel biomaterials for use in retrofits. Her writing on the history of preservation, reuse, and urbanism has been published in JSAH, Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes, and the book Ruskin’s Ecologies, among other publications. She has previously taught at Georgia Tech and Rice. She has her MArch from Princeton and her PhD in Oncology from Cambridge University. Roark’s proposed project is titled “Biomaterial Protocols: From Waste to Walls.”

Prizes & Honors 2024

Each year at commencement, the Harvard Graduate School of Design confers awards on graduating students who demonstrate exceptional scholarly achievement, leadership, and service. Congratulations to the student award recipients, and to all 2024 graduates for your tremendous accomplishments.

Prize-Winning Thesis Projects

KEUR FÀTTALIKU — The House of Recollection

Mariama M.M. Kah (MArch II ’24)

Bådehus

Yeonho Lee (MArch II ’24)

How to (Un)build a House? A Reinvention of Wood Framing

Clara Mu He (MArch I ’24)

Learning from Quartzsite, AZ: Emerging Nomadic Spatial Practices in America

Mojtaba Nabavi (MAUD ’24)

Reforesting Fort Ord

Slide Kelly (MLA I AP, MDes ’24)

INSURGENT GEOLOGY: Mineral Matters in the Arctic

Melanie Louterbach (MLA I ’24)

Seeding Grounds: Working Beyond Arcadia in The Pyrocene

by Stewart Crane Sarris (MLA I ’24)

School Awards

Gerald M. McCue Medal

The Gerald M. McCue Medal is awarded each year to the student graduating from one of the school’s post-professional degree programs who has achieved the highest overall academic record.

- Haewon Ma (MDes ’24, Narratives Domain)

Digital Design Prize

The Digital Design Prize is presented by the Graduate School of Design to the students who have demonstrated the most imaginative and creative use of computer graphics in relation to the design professions.

- Chun Tak Chung (MArch I AP ’24)

Peter Rice Prize

The Peter Rice Prize honors students of exceptional promise in the school’s architecture and advanced degree programs who have proven their competence and innovation in advancing architecture and structural engineering.

- Clara Mu He (MArch I ’24)

Plimpton-Poorvu Design Prize

The Plimpton-Poorvu Design Prize recognizes the top team or individual for a viable real estate project completed as part of the GSD curriculum that best demonstrates feasibility in design, construction, economics, and in fulfillment of market and user needs.

- 1st Prize: Ziyang Dong (MArch I ’25)

- 1st Prize: Jasmine Ibrahim (MRE ’24)

- 1st Prize: Jian Li Oh (MUD ’24)

- 1st Prize: Benjamin John Parker (MAUD ’24)

- 2nd Prize: Chandler Caserta (MArch I ’25)

- 2nd Prize: Austin N Sun (MArch I, MLA AP ’24)

- 2nd Prize: Kei Takanami (MArch I ’25)

- 2nd Prize: Amber Zeng (MArch I ’25)

- 2nd Prize: Catherine Shuying Chen (MArch I ’25)

- 2nd Prize: Aaron Smithson (MArch I, UP ’25)

- 2nd Prize: Maggie May Weese (MUP, MPH ’24)

- Honorable Mention: Jaime Espinoza (MRE ’24)

- Honorable Mention: Chris James (MRE ’24)

- Honorable Mention: Miguel Lantigua Inoa (MArch II, MLA AP ’24)

Clifford Wong Prize in Housing Design

The Clifford Wong Prize in Housing Design aims to help re-establish the essential role of architects in society to provide not only the fundamental needs of human shelter but to meet the challenge of designing creative solutions for improving living environments. The prize is awarded for the multi-family housing design that incorporates the most interesting ideas and/or innovations that may lead to socially oriented, improved living conditions.

- Magdalen Elizabeth Musante (MArch I ’24)

Best Paper on Housing

- Jorge Enrique Mutis (MAUD ’24)

Irving Innovation Fellowship

The Irving Innovation Fellowship offers a graduating student the opportunity to extend their research and discovery beyond their time as a student and work with a group of mentors and colleagues to contribute to the school’s pedagogy and dialogue on an annually changing topic.

- Melanie Louterbach (MLA I ’24)

Fulbright Public Policy Fellowship

- Kimberlee Diane Córdova (MDes ’24, Narratives Domain)

Druker Traveling Fellowship

Established in 1986, the Druker Traveling Fellowship is open to all students at the GSD who demonstrate excellence in the design of urban environments. It offers students the opportunity to travel in the United States or abroad to pursue study that advances understanding of urban design.

- Curry Julius Hackett (MAUD ’24)

Architecture Awards

American Institute of Architects Medal

The American Institute of Architects Medal is awarded to a professional degree student in the Master in Architecture graduating class who has achieved the highest level of excellence in overall scholarship throughout the course of their studies.

- Sungyeon Kristine Chung (MArch I ’24)

Alpha Rho Chi Medal

The Alpha Rho Chi Medal is awarded to the graduating student who has achieved the best general record of leadership and service to the department and who gives promise of professional merit through their character.

- Oluwatosin Odugbemi (MArch I ’24)

James Templeton Kelley Prize

The James Templeton Kelley Prize recognizes the best final design project submitted by a graduating student in the architecture degree programs.

- MArch I: Clara Mu He (MArch I ’24)

- MArch II: Mariama M.M. Kah (MArch II ’24)

- MArch II: Yeonho Lee (MArch II ’24)

Julia Amory Appleton Traveling Fellowship in Architecture

The Julia Amory Appleton Traveling Fellowship is given to a student in the Department of Architecture on the basis of academic achievement as well as the worthiness of the project to be undertaken.

- Magdalen Elizabeth Musante (MArch I ’24)

Kevin V. Kieran Prize

The Kevin V. Kieran Prize recognizes the highest level of academic achievement among students graduating from the post-professional Master in Architecture program.

- Thomas Day (MArch II ’24)

Dept. of Architecture Faculty Design Award

The Department of Architecture Faculty Design Award was established by the faculty of the Department of Architecture with the aim of recognizing significant achievement within a body of design work completed by a student at the GSD. This award is given to graduating students from each of the department’s two program.

- Siyu Zhu (MArch I ’24)

- Ihwa Choi (MArch II ’24)

Dept. of Architecture Certificate of Academic Excellence

The Department of Architecture Certificate of Academic Excellence is awarded by the faculty of the Department of Architecture to a graduate of the professional degree program in architecture (MArch I) in recognition of their academic achievement throughout their course of study in the program.

- Nana Komoriya (MArch I ’24)

Landscape Architecture Awards

Thesis Prize in Landscape Architecture

The Landscape Architecture Thesis Prize is given to the graduating student who has prepared the best independent thesis during the past academic year.

- Slide Kelly (MLA I AP, MDes ’24)

- Melanie Louterbach (MLA I ’24)

- Stewart Crane Sarris (MLA I ’24)

American Society of Landscape Architects Certificates

Nominated by the faculty in the GSD’s Department of Landscape Architecture, the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) awards a certificate of Honor and a Certificate of Merit to students enrolled in the Master in Landscape Architecture program who have “demonstrated a high degree of academic scholarship and of accomplishment in skills related to the art and technology of landscape architecture.”

- Leila Sophia Breen (MLA I ’24), Certificate of Merit

- Julia Leah Hedges (MLA I ’24), Certificate of Merit

- Kai Alycia Walcott (MLA I ’24), Certificate of Merit

- Brian Kohan (MLA I AP ’24), Certificate of Honor

- Xinran Ma (MLA I ’24), Certificate of Honor

- Zeinab Maghdouri Khubnama (MLA I AP ’24), Certificate of Honor

Norman T. Newton Prize

The Norman T. Newton Prize is given to a graduating landscape architecture student whose work best exemplifies achievement in design expression as realized in any medium.

- Christopher Lucas Dobbin (MLA I AP ’24)

Peter Walker & Partners Fellowship for Landscape Architecture

The Peter Walker and Partners Fellowship for Landscape Architecture is awarded to support travel and study for a graduating GSD student to advance their understanding of the body of scholarship and practices related to landscape design.

- Gracie Rae Meek (MLA I AP ’24)

- Daniella Renee Slowik (MLA II ’24)

Jacob Weidenman Prize

The Jacob Weidenmann Prize is awarded to the student of the most distinguished design achievement graduating from the Department of Landscape Architecture.

- Nakakamol Chueathue (MLA II ’24)

Charles Eliot Traveling Fellowship in Landscape Architecture

The Charles Eliot Traveling Fellowship is awarded annually as the highest honor by the Department of Landscape Architecture to one of its graduates.

- Stewart Crane Sarris (MLA I ’24)

Urban Planning and Design Awards

Academic Excellence in Urban Planning

The Award for Academic Excellence in Urban Planning and Urban Design honors graduating students from each of the programs who have achieved the highest academic record.

- Daniel Montoya (MUP ’24)

- Michael Christopher Whelan (MUP ’24)

Academic Excellence in Urban Design

- Benjamin John Parker (MAUD ’24)

Award for Outstanding Leadership in Urban Planning and Urban Design

The Award for Outstanding Leadership in Urban Planning and Urban Design honors graduating students from each of the programs who have demonstrated outstanding leadership during their time at the Graduate School of Design.

- Olufemi Olamijulo (MUP ’24)

- Pia Kochar (MAUD ’24)

Thesis Prize in Urban Planning & Design

The Planning and Design Thesis Prize is given to the graduating students in each of the programs who have prepared the best independent theses during the past academic year.

- Mojtaba Nabavi (MAUD ’24)

Award for Excellence in Project-Based Urban Planning

The Award for Excellence in Project-Based Urban Planning is given to students who have demonstrated exceptional ability in urban planning projects including research and design studios throughout their course of study.

- Nur Shlapobersky (MUP ’24)

Award for Excellence in Urban Design

The Award for Excellence in Urban Design is given to students who have demonstrated exceptional design ability throughout their course of study in the Urban Design program.

- Yimeng Ding (MAUD ’24)

American Planning Association Outstanding Student Award

The American Planning Association Outstanding Student Award recognizes outstanding attainment in the study of planning by students graduating from accredited planning programs. The recipient of the award is chosen by a jury of planning faculty at each school.

- Briana Villaverde Uriarte (MUP ’24)

Design Studies Awards

Dimitris Pikionis Award

The Dimitris Pikionis Award recognizes a student for outstanding academic performance in the Master in Design Studies degree program.

- Rosita Palladino (MDes ’24, Ecologies Domain)

Design Studies Domain Awards

- Rosita Palladino (MDes ’24, Ecologies Domain)

- Treyden Chiaravalloti (MDes ’24, Mediums Domain)

- Huirong Ye (MDes ’24, Narratives Domain)

- Gabriel Jean-Paul Soomar (MArch II, MDes ’24, Publics Domain)

Design Engineering Awards

Overall Academic Performance Award

The Overall Academic Performance Award recognizes a graduating MDE student for outstanding academic performance in the Master in Design Engineering degree program.

- Binita Gupta (MDE ’24)

Leadership and Community Prize

The Leadership and Community Prize recognizes one or more graduating students who have displayed outstanding leadership and community building within the Design Engineering cohort and who have represented MDE values to the larger world.

- Ghalya Alsanea (MDE ’24)

- Priyanka Pillai (MDE ’24)

Outstanding Design Engineering Project

- Priyanka Pillai (MDE ’24)

- Julius Stein (MDE ’24)

Alumni Award

The Alumni Award recognizes and celebrates the diversity, range, and impact of outstanding GSD alumni leaders within their communities and across their areas of practice. It underscores the essential role GSD graduates play in leading change around the world. Founded and led by the GSD Alumni Council, 2024 marks the fourth year of this initiative.

Ron Ostberg, who received his Master in Architecture (MArch) from the GSD in 1968

Ron Ostberg receives this award for exceptional service to the GSD community, outstanding ambassadorship to the school through the broader university and Harvard Alumni Association, and for playing a critical role in forming the Alumni Council as we know it today.

Gretchen Schneider Rabinkin, who received her Master in Architecture (MArch) from the GSD in 1997

As Executive Director, Gretchen Schneider Rabinkin oversees operations and management of the Boston Society of Landscape Architects, one of the largest, oldest, and most active chapters of the American Society of Landscape Architects.

Harry G. Robinson, III, who received his Master in City Planning in Urban Design from the GSD in 1973

Harry G. Robinson is a former professor of architecture and Dean Emeritus of the School of Architecture and Design at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

Calvin Tsao, who received his Master in Architecture from the GSD in 1979

Calvin Tsao is a recognized and leading voice in contemporary architecture whose work draws from a lively engagement with a variety of art forms.

2024 Graduating Student Profiles

Meet members of the Harvard Graduate School of Design Class of 2024. These students represent the departments and disciplines that define the GSD’s unique approach to design education. Their work exemplifies the School’s mission to make a resilient, just, and beautiful world.

Mariama M.M. Kah (MArch II ’24)

Daniella Slowik (MLA ’24)

Curry J. Hackett (MAUD ’24)

Haewon Ma (MDes ’24)

Binita Gupta (MDE ’24)

Resourceful Urbanism: Dan Stubbergaard’s Adaptive Reuse of Cities

Even before the last flight had taken off from Berlin’s Tempelhof Airport, in 2008, the future of the historic airport’s 355-hectare site was the subject of intense dispute. Competing plans to transform the area into new residential neighborhoods and commercial areas, integrating the vast airfield into the surrounding urban fabric, stalled amid protests against development. Instead, the airport reopened as Tempelhofer Feld, the city’s largest public park. The proximity to the city center that had made the airport a commuter hub also contributed to the park’s popularity, even with intact runways crossing the open greenspace. Yet amid demands for more affordable housing and increasing concerns about sustainable growth amid the climate crisis, the future of the vast Tempelhof site and its surroundings remains unclear.

In the Spring 2024 option studio City as Resource, GSD Professor in Practice of Urban Design Dan Stubbergaard challenged students to develop plans for new housing in an area surrounding the Teltow Canal, which runs just south of Tempelhofer Feld. The concept of adaptive reuse is at the core of Stubbergaard’s studio, as well as his own practice. Rather than seeking proposals to tear down existing structures or build new ones, Stubbergaard asked students to explore how “retrofitting existing situations can contribute to the creation of neighborhoods with improved living conditions, sense of community, and social balance.” Beyond conserving resources, wise applications of adaptive reuse can support growth that reflects established communities, especially in a city like Berlin that has an existing tradition of repurposing buildings.

In an April 9 talk at the Graduate School of Design , also titled “City as Resource,” Stubbergaard described himself as “a very strong believer in the city and also the city as a design phenomenon, which can solve and deal with many of these challenges we have faced, but also are facing in the future.” He pointed to targets set by the European Union to eliminate net carbon emissions by 2050 while also restricting the use of new land for development. These parameters make adaptive reuse a necessity since existing structures constitute embodied carbon—an investment in emissions made by previous generations. Adaptive reuse is especially effective when combined with planning approaches geared toward density, which allows for more efficient transportation and energy use. Stubbergaard described his mission to define “how we live closer, live smarter, and also create better social solutions in a much more dense environment than we have used to before.”

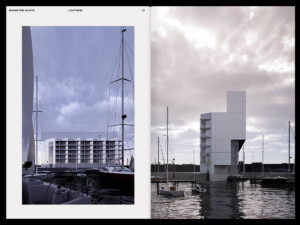

Stubbergaard presented an overview of work being done by Cobe, his Copenhagen-based firm. Since its founding in 2006, Cobe has built more than 36 projects in its home city alone. Some of the firm’s most iconic projects are in Nordhavn, a former industrial waterfront that Cobe won the competition to masterplan in 2008. This multi-decade project is adaptive reuse at an urban scale, with a network of docks to create a new neighborhood of dense housing connected by transit and bike lanes. The 160 architects, landscape architects, and urban designers who now make up Cobe live out the group’s principles by working together in an office in a repurposed warehouse in Nordhavn.

The firm’s work focuses on seven thematic areas: resilient urban development, infrastructure for a changing climate, adaptive reuse, longevity and adaptability, new ways of building, social capital, and urban nature. “I think we need to see our profession as creators of solutions for the future,” Stubbergaard said. Among the most stunning efforts at adaptive reuse is The Silo, a former grain silo that Cobe transformed into a residential complex with public facilities on the ground floor and roof. The project reused 2700 cubic meters of concrete. Cobe’s plan for the Frederiksberg School of Culture and Music repurposed parking space into a series of courtyards on the grounds of the Radio House, the former headquarters of the Danish Broadcasting Corporation. The Roskilde Folk High School, another arts-focused high school, sits on the site of a former concrete factory whose existing structures have been transformed into space for art workshops, dance halls, and music studios.

In Stubbergaard’s studio, students began the semester by dividing up into teams of two, each focusing on one of six themes: vacancy and obsolescence, urban expansion, underutilization, density, land use, and zoning. During the studio’s trip to Berlin in February, they were able to visit the site and choose a section of the site to focus on. In addition to the site visits, the studio spent time at several architecture firms to observe their approaches to sustainable practice. They climbed 22 floors of an old industrial building to reach the offices of b+, a firm specializing in adaptive reuse. They had a guided tour of Lokdepot, a residential area featuring recycled brick facades. At the offices of Bauhaus Erde, they made their own bricks out of compacted soils.

Despite having studied maps of the site and the city in the first part of the semester, Christopher Oh and Somin Lee (MAUD ’24) found that their experiences walking around Berlin brought home why Stubbergaard had chosen this city in particular. “In Berlin [adaptive reuse] is part of the culture,” said Oh, “but it didn’t come from a climate perspective.” Rather, it was a financial necessity after the war. Their eventual project proposed reuse of over 60 percent of the existing buildings on their section of the site, which connected the airport to the canal via a long strip, to provide housing; meanwhile, they added green spaces to promote community agriculture and pedestrian connectivity.

Gyu-Lee Hwang and Hui Li (both MAUD ’25) proposed relocating a mixed-use development currently being developed on the site of the Tempelhof airport to the former industrial area along the Teltow Canal. They explained, “Berlin is well known for applying mixed-use developments, but still they have this kind of zoning – residential and industrial [are] separated. Our site is located to the south of the Tempelhof airport along the Teltow canal. It’s very historic and is open to the public now. But they have this plan of using that green space to develop the housing because they have this population growth [projected to increase by nearly 200,000 inhabitants by 2040] and housing shortage problems.” They were inspired by the time they spent on their trip observing Berlin’s Höfe, linked courtyards that can be used as parks, playgrounds, retail businesses, or other community spaces for the residential housing that surround them. Hwang and Li proposed to turn the existing airport parking area into a series of Höfe.

As Stubbergaard noted in his talk, the construction industry accounts for 40 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, 60 percent of resource consumption, and 40 percent of waste generation. Stubbergaard believes that adaptive reuse is an ideal tool to help mitigate these problems. Indeed, more than 50 percent of Cobe’s current projects involve adaptive reuse on some level. The growing impact of adaptive reuse on the design fields has made students eager to learn about the topic as well. Christopher Oh says that “[Adaptive reuse] is definitely going to be a huge part of the profession in the future. I feel that there’s a huge push not just amongst us as students, wanting to engage more with it, but also people working in governments.”

The lessons that Stubbergaard and Cobe learned in their ongoing project of rebuilding the Nordhavn district are ones that he has tried to help the students apply to their Tempelhof sites. Like the reimagined Nordhavn, the studio projects prioritize pedestrian access and intersperse green space among residential areas, cultural and community space, and businesses.

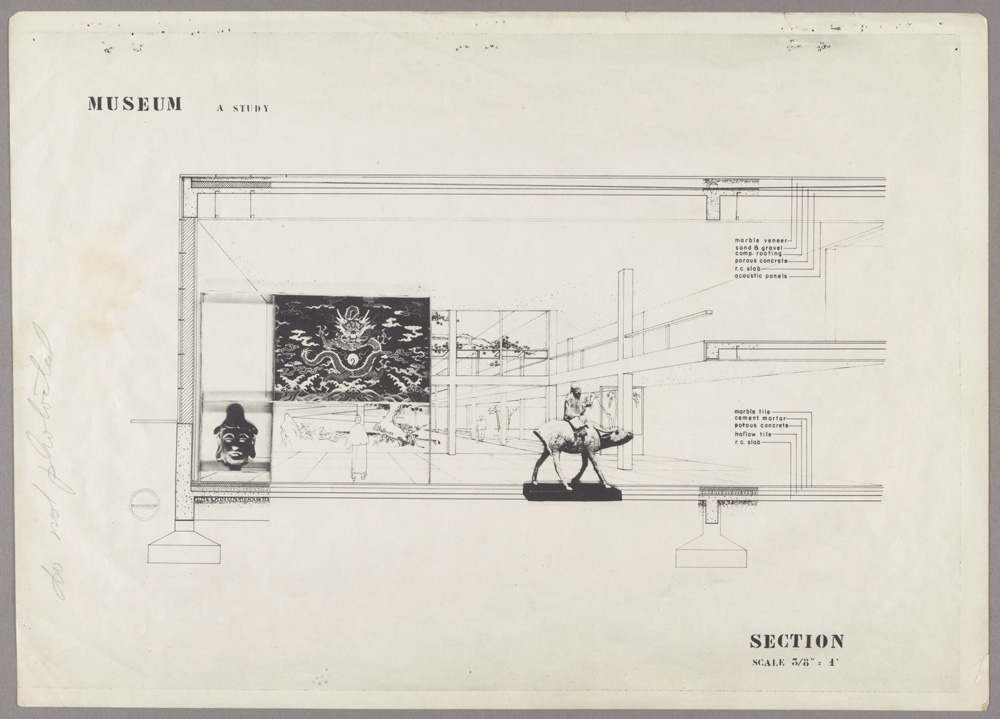

Rethinking I.M. Pei’s Legacy

For his 1946 thesis at Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), Ieoh Ming (I.M.) Pei proposed a museum in Shanghai. Intended to display Chinese art, the structure embodies a proposition about the changing nature of cultural and civic institutions in the cosmopolitan city where Pei spent his early life—a city that had since been transformed by war and was on the verge of revolution. The project’s modernist form attests to Pei’s time studying under Walter Gropius while its spatial layout, organized around courtyards, recalls precedents in Chinese architecture. Such subtle transcultural sensitivity characterizes Pei’s six-decade career, which is now set for a major reassessment.

“He was always interested in trying to find buildings that would enliven the community in which they existed,” said I.M. Pei’s son Li Chung (Sandi) Pei (AB ’72, MArch ’76). On May 15 at Cooper Union in New York, Sandi Pei shared reflections on his father’s life and work with Calvin Tsao (MArch ’79) in a conversation moderated by architecture critic Paul Goldberger.

The event, organized by the M+ American Friends Foundation, previewed the architect’s first major retrospective, I.M. Pei: Life is Architecture , opening this summer at M+ in Hong Kong. Curated by Aric Chen and Shirley Surya, the exhibition has roots at the GSD, where “Rethinking Pei: A Centenary Symposium” took place in 2017. Several of the papers presented at the symposium have been adapted for the publication that accompanies the exhibition.

Sandi Pei and Tsao shared memories of working with I.M. Pei on now-seminal projects. Tsao joined the firm Pei Cobb Freed as a fresh graduate of the GSD. He jokingly recalled how, as a junior staff member, he received an assignment “counting bathroom tiles” for the design of the Javits Center. Yet his work eventually caught the attention of the firm’s principal, and Tsao joined the project team for the Fragrant Hill Hotel in Beijing, one of the first significant international projects developed during the period of economic reform in China.

I.M. Pei was as adept at navigating the world of New York developers as he was in conveying his design philosophy to members of the public where he worked. Both Tsao and Sandi Pei had roles on the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong, a building notable for its imposing structure of triangular supports designed to withstand typhoon winds. Yet as Tsao recalled, I.M. Pei understood the skyscraper in terms of a Chinese saying, “the bamboo shoot rising ever higher under the spring rain.” As Tsao said, “It’s not just technical engineering, but also it derived from that cultural, literary context.” Tsao also recalled Pei sharing Chinese landscape paintings as part of the design research process for the Fragrant Hill Hotel.

2021. Commissioned by M+, 2021. © South Ho Siu Nam

I.M. Pei did not return to the academy after he started his practice, but as Sandi Pei noted, “we often said working in the office was like being in a university,” with employees earning a rigorous “I.M. degree.” He recalled his father bringing strong ideas to a project but also allowing them to evolve through the design process, often with crucial input from others, as on the CAA building in Los Angeles. “He felt that the way to teach was through his buildings,” said Sandi Pei, “and he welcomed people to look at what he was doing and challenge the ideas.” As Tsao added, “I think he would make an incredible teacher. Not one who lectures, but someone who could actually sit side-by-side with you.”

While the panelists shared such candid reflections on the man who mentored them, they also alluded to another side of I.M. Pei as a public figure and veritable diplomat responsible for high-profile projects like the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., and the renovation of the Louvre in Paris. Almost transcending his role as an architect, Pei courted political favor from successive French politicians and American elites, including Jaqueline Kennedy (one section of the M+ exhibition is titled “Power, Politics, and Patronage”.)

Yet one member of the audience voiced a question that was also raised at the GSD symposium: despite his legacy of iconic buildings, is I.M. Pei, in fact, underrated? “In the Venn diagram of architects who work for developers and architects who are widely admired,” Goldberger speculated, “I think there’s only one tiny bit of overlap”—just enough for I.M. Pei. The architect’s once-controversial decision to work for the real estate developer William Zeckendorf early in his career is one of the prime areas ripe for reassessment today. A study of Pei’s business acumen, as a complement to his visionary designs, suggests in particular possible strategies for the development of high-quality affordable housing.

© Marc Riboud/Fonds Marc Riboud au MNAAG/Magnum Photos