Loeb Fellowship announces its incoming Class of 2020

They are architects and artists, activists and curators, policy-makers and transit advocates at the highest levels of their fields—and they are about to dedicate themselves to a year of research and engagement at Harvard University Graduate School of Design (Harvard GSD) as they consider how their work might advance equitable social futures.

Each year, Harvard GSD’s Loeb Fellowship program welcomes a cohort of exceptional mid-career practitioners, each of whom is involved in shaping the built environment, for a year of research, dialogue, and innovation. Loeb Fellows are selected through a highly competitive global application process; the nine 2020 fellows were selected from among over 100 candidates.

The incoming Loeb Fellows are:

Pedro Gadanho (Director, Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology; Lisbon, Portugal)

Elizabeth Kay Miller (Executive Director, Community Design Collaborative; Philadelphia, PA)

Deborah Helaine Morris (Executive Director of Resiliency Policy, Planning, and Acquisitions, New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development; New York, NY)

Eleni Myrivili (Deputy Mayor for Urban Nature, Resilience & Climate Change Adaptation, City of Athens; Athens, Greece)

De Nichols (Social Impact Design Principal, Civic Creatives; St. Louis, MO)

Wolfgang Rieder (Entrepreneur and Circular Economy Activist, Rieder Group; Salzburg, Austria)

Andrew Salzberg (Head of Transportation Policy and Research, Uber; San Francisco, CA)

Paloma Strelitz (Co-Founder and Partner, Assemble; London, UK)

Michelle Joan Wilkinson (Museum Curator and Acting Associate Director for Curatorial Affairs, Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture; Washington, D.C.)

Drawing on diverse backgrounds and passions, each Loeb Fellowship cohort arrives at Harvard GSD with a common purpose: to strengthen their abilities to advance positive social outcomes and equity. Among other activities during the course of their year-long residencies, Loeb Fellows immerse themselves in the academic environment, auditing courses across vast offerings at Harvard and MIT, challenging their ideas and processes, and expanding their professional networks. Fellows also engage with Harvard GSD students and faculty, participate as speakers and panelists at public events, and convene workshops and other activities that encourage knowledge sharing and creation. Throughout, fellows consider how they might broaden or refocus their careers and the impact of their work, and encourage deeper social engagement with it.

“The Fellowship has an important role in the design world,” observes Loeb Fellowship program curator John Peterson. “In spite of the design profession’s often indifference to its social consequence, for almost 50 years the Fellowship has steadfastly championed those who are shaping the built environment as significant players for positive social outcomes.”

After their year of Harvard GSD residence, Loeb Fellowship alumni join a powerful worldwide network of over 450 lifelong Loeb fellows. Alumni include Cathleen McGuigan, Theaster Gates, Toni L. Griffin, Alejandro Echeverri, Anna Heringer, Inga Saffron, Damon Rich, and Phil Freelon.

The Loeb Fellowship traces its roots to 1968, when John L. Loeb was directing a Harvard GSD campaign themed around “Crisis.” Loeb saw the American city in disarray and believed Harvard could help. He imagined bringing highly promising innovators of the built and natural environment to Harvard GSD for a year, challenging them to do more and do better, convinced they would return to their work with new ideas and energy.

John Loeb and his wife Frances endowed the Loeb Fellowship as part of their gift to the “Crisis” campaign. They worked closely with William A. Doebele, the Frank Backus Williams Professor of Urban Planning and Design (now Emeritus), the program’s founding curator, who guided the program through its first 27 years and shaped an experience that has had a powerful impact on generations of urban, rural, and environmental practitioners.

Today, the Loeb Fellowship is led by program curator John Peterson, architect, activist, and founder of Public Architecture, a national nonprofit organization, and himself a program alumnus.

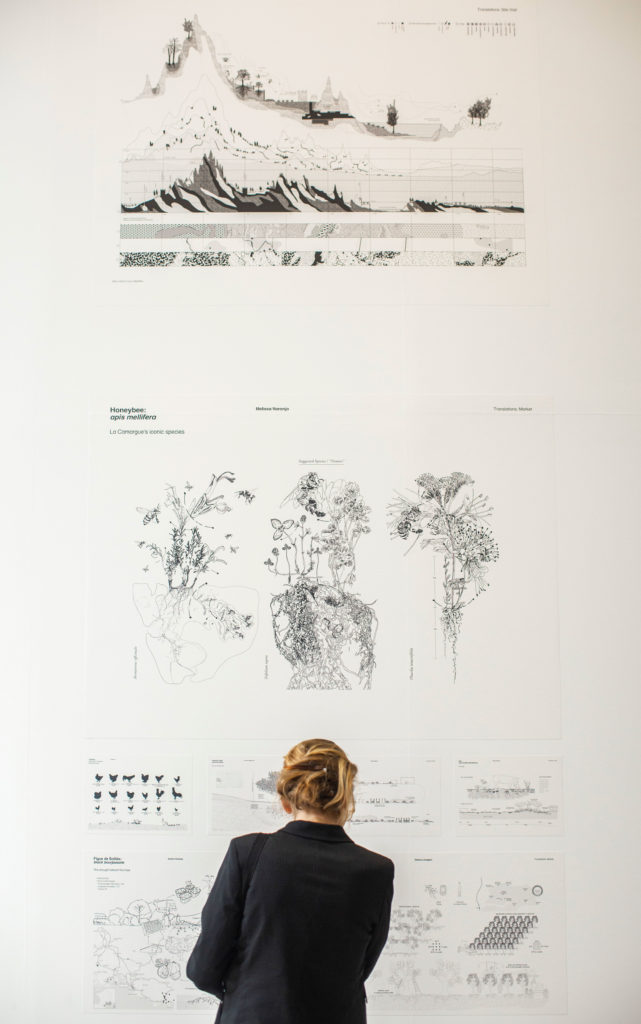

Regenerative Empathy exhibition shares studio’s findings with the French community that inspired it

Humans have exploited soil—truly, much of nature—for millennia. Soil can hold eras’ worth of stories and history, human and natural. And the soil surrounding plants’ roots, teeming with microorganisms and their constant activity, provides a particular design space. This space of life—called the rhizosphere—is the platform for delicate interactions between climate and geology, a site of layering of events and histories over time.

It was with interest in this design space that Teresa Galí-Izard, Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture, conceived her Fall 2018 Harvard Graduate School of Design option studio “RHIZOSPHERE.” The studio sought to investigate the rhizosphere and the stories it can tell, taking up the Mediterranean region of La Camargue, France, as its site of focus. And thanks to engagement from the Luma Foundation, the studio’s findings have been brought back to the ground that inspired them, in the form of an exhibition that was on view for the month of May at Luma’s Parc de Ateliers space in Arles, France.

Framing the studio’s work was the question of how, as seen through the rhizosphere, living things—human and animal alike—can foster regenerative agriculture as a means of managing and improving the land. As Galí-Izard writes in the course’s resultant Studio Report, she and her studio have sought to regenerate the rhizosphere as a biological, living entity by creating new associations and synergies between humans and other living systems.

“Although the studio has a strong technical component, it is ultimately a political project that pursues more equal status between all forms of life,” says Anita Berrizbeitia, Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture. “It thus raises the larger question of the relationship between humans and the natural world, and the role of landscape architecture in creating a more distributed agency of, and collaboration between, people, animals, vegetation, weather and other abiotic factors, technology, and energy in the era of climate change and the aftermath of environmental ruin.”

The exhibition, entitled Regenerative Empathy, joined a series of other installations for Luma’s show “A School of Schools: Design as Learning.” True to the studio’s general approach, the “Regenerative Empathy” exhibition shares student findings through a shared language: black-and-white line drawing, which Galí-Izard calls a “restrictive lens” that begets common ground for different sources of knowledge and information, be it geological maps, data from climate, field observations, scientific articles, or other material.

The findings presented by the studio and exhibition span approaches, scales, and materials. Animals prove fundamental to many proposals: One suggested a continuous system of anchored pastures in the Les Alpilles mountains, from which goats—outfitted in a seasonal “wardrobe”—disperse seed and regenerate soil. Elsewhere, a landscape of pigs and peach trees finds harmony between the formality of pruned, carefully maintained trees and the messy, unpredictable natural habits of pigs. Rabbits, bulls, and other animal species figure prominently in various proposals, illustrating the dynamic natural feedback loops that characterize agricultural processes in the region.

Elsewhere, students proposed new or modified bodies of water as change agents. One project illustrates a system of collection ponds along existing draining channels, working together with Italian cypress and sheep, cattle, fruit trees, and rice to create a dynamic and life-providing landscape on what had been forgotten margins.

Throughout, Galí-Izard urged students to wonder how their proposals might encourage a new form of empathy—a regeneration and a new system of maintenance and care for land that has been taken advantage of for millennia.

“In the search for what our contribution to La Camargue could be, we found that empathy and freedom were critical,” she writes. “Empathy as an elastic trajectory that brought us from here to there; and freedom as an open window to imagine a different future without prejudices, and with our spirits alive.”

Exhibition views, “A School of Schools: Design as Learning.” Luma Arles, Parc des Ateliers, Arles (France). © Joana Luz.

Excerpt from Harvard Design Magazine: “The Interior as Setting”

The interior was always part of the modernist agenda. From Le Corbusier’s dictum “The plan is the generator” to Ernst Neufert’s Bauhaus-inspired Architects’ Data (1936), the interior, and how it was to be occupied or possibly “standardized,” was an indispensable part of how architects thought about and planned their buildings. The inside was typically measured in relation to the organization of human habitation. The precision of these activities or “functions” assumed an objective and rational dimension and was reduced to the bare bones of an Existenzminimum. In much of the housing stock of the postwar period these ideas oscillate between the beauty and purity of monastic frugality— the relinquishing of earthly goods—and the sheer meanness of cramped living conditions. The reduced scale of this type of architecture is a direct reflection of the minimum dimensions and measures of the inside: its living rooms and bedrooms, its tiny bathrooms and “Taylorist” kitchens. Life is reduced to the mere reenactment of functional routines, stripped of any form of spatial pleasure.

The situation has changed. No one questions that one of the main tasks of architecture today is to provide as much space as possible within a given budget. Architects such as the distinguished French firm Lacaton & Vassal have made some extraordinary adjustments to a number of classic social housing projects, expanding the building envelope and providing the inhabitants with a more generous footprint and a more pleasurable spatial experience. In London, some local councils are entrusting creative private practices with the design of a new generation of public housing: well-built, light-filled schemes that provide the internal features, such as balconies and winter gardens, that tenants want—all of it cross-subsidized by the addition of market-rate housing.

On the whole, however, the interior is no longer a territory of explicit and intentional exploration, as it was for architects such as Le Corbusier or Adolf Loos. In the context of the academy, it has become the domain of specialized study in interior design and interior architecture programs and essentially translates to interior decorating in everyday practice and common parlance. The links to life have been supplanted by the practice of decoration.

It is imperative for architecture to reclaim the interior and to once again make it an inseparable part of its discourse. The interior requires an entanglement of art and design, of aesthetic pleasure, and of the fulfillment of everyday functions. How a building is used is not solely rational but requires a consideration of the daily rituals of sitting, sleeping, conversing, eating, cooking, bathing, dining, reading. Each of these activities, and others, demands imaginative spatial responses, designs that will enable the occupant of the interior to be located within a specific environment. These spaces house furniture as well as other artifacts—equipment—that provide an appropriate setting for the actions and uses that are to take place within its boundaries.

The positioning of furniture enables multiple traces of the choreography to be performed within a given space. Akin to a theatrical setting, the furniture and its arrangement within the space should open up possibilities, rather than close them in the way Architects’ Data often does by making the minimum standards of organization the norm.

It is perhaps not surprising that time and time again one is drawn to the interior’s presence within the context of cinema—and, more specifically, to how different cinematographers capture the interactions among actors, and their relationship to and use of indoor settings. The artifice of cinema renders the relationality between the figure and the space more explicit, “denaturalized,” unlike the often-fleeting nature of this encounter within everyday life.

A decade after Harvard Design Magazine’s first issue on the topic of the interior, it is only fitting that it should remind us all once again of the importance of what lies inside architecture and how it helps to frame and shape our habits and actions.

“The Interior as Setting” is excerpted from Issue No. 47 of Harvard Design Magazine: Inside Scoop . It was written in response to Architecture’s Inside by Mohsen Mostafavi, which was originally published in 2008 as part of Issue No. 29: What About the Inside? .

A momentous year: Highlights from 2018–2019 at Harvard Graduate School of Design

A look back at a few of the projects and moments that marked the past year at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

June 2018

Thirty-five students are awarded fellowships through the GSD’s Community Service Fellowship Program (CSFP). The Program provides opportunities for GSD students to apply the skills they have developed in their academic programs through direct involvement with projects that address public needs and community concerns at the local, national, and international level.

“Wavelength,” a public art installation designed by the GSD’s Daniel D’Oca (MUP ’02) and his colleagues at Interboro Partners, Tobias Armborst and Georgeen Theodore (both MAUD ’02), brings color and shade to Harvard’s Science Center Plaza.

Farshid Moussavi is recognized with an Order of the British Empire award amid the Queen’s Birthday Honours. Moussavi receives an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire award in recognition of her contributions to the field of architecture.

July 2018

The GSD selects the Basel-based architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron, design consultant, and New York-based Beyer Blinder Belle (BBB), architect of record, to design a significant transformation of the School’s primary campus building, Gund Hall, into a twenty-first-century center of design education and innovation.

The GSD-Courances Design Residency names its inaugural participants: Mariel Collard (MLA, MDes ’19) and Juan David Grisales (MLA, MDes ’20).

Andres Sevtsuk talks autonomous vehicles, Future of Streets research during a keynote address at the Strategic Visioning Workshop on Autonomous Vehicles conference in Minnesota.

August 2018

The Fall 2018 public program is announced, offering a lecture from Michael Van Valkenburgh, a conversation with Hannah Beachler, and an evening with Hans Ulrich Obrist, among many others.

“I hope my students will leave class seeing themselves as more empowered citizens.” Urban Planning and Design’s Abby Spinak discusses the courses she is leading this fall, what she hopes students will take away from them, and her design inspiration outside the classroom.

The American Planning Association (APA) honors two GSD candidates as recipients of each of its two APA Foundation Scholarship awards: Gina Ciancone (MUP ’19) and Henna Mahmood (MUP ’20).

September 2018

Talking Practice podcast—the first podcast series to feature in-depth interviews with leading designers on the ways in which architects, landscape architects, designers, and planners articulate design imagination through practice—debuts. Hosted by Grace La, initial guests include Reinier de Graaf, Jeanne Gang, and Paul Nakazawa.

The Guardian taps the GSD’s Jesse M. Keenan for a series on “climate migration” in America.

The culmination of a four-year investigation funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Druker Design Gallery exhibition Urban Intermedia: City, Archive, Narrative argues that the complexity of contemporary urban societies and environments makes communication and collaboration across professional boundaries and academic disciplines essential.

October 2018

Mohsen Mostafavi, Dean and Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design, announces his intention step down at the end of the 2018-19 academic year. “I am proud of what we have accomplished together over the past 11 years, and I look forward to witnessing the School continue its collaborative ethos and engagement with Harvard and the world in the years to come.”

Nine GSD students and recent graduates are among the recipients of 2018 American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) Student Awards.

Sou Fujimoto discusses the relationship between nature and architecture as well as that between nature and man-made environment as part of the fall public program.

UPD’s Ann Forsyth is named Editor of Journal of the American Planning Association (JAPA). “Professor Forsyth is a visionary among her peers in the planning profession, with an impressive record in both academia and professional practice,” says APA President Cynthia Bowen.

November 2018

Friends of The High Line, 2017 Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design winner, is honored through an exhibition in the Druker Design Gallery.

Internationally renowned graphic designer Irma Boom delivers the 2018 Open House Lecture.

Platform 11: Setting the Table, the first student-led installment of the series, debuts at Open House.

Womxn in Design hosts “A Convergence at the Confluence of Power, Identity, and Design.” It marks the formation of a regional network of equity-focused design-centric student groups focused on re-imagining the intersection between identity and design.

December 2018

The Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities (CGBC) announces the completion of HouseZero, the retrofitting of its headquarters in a pre-1940s building in Cambridge into an ambitious living laboratory and an energy-positive prototype for ultra-efficiency that will help us to understand buildings in new ways.

“No Sweat,” the 46th issues of Harvard Design Magazine, takes on the design of work and the work of design.

The six winners of the 2019 Richard Rogers Fellowship are announced. The cohort includes a range of participants from academia, architecture, and media arts.

Students in studio courses present their work to critics from the GSD and around the world during final reviews. Image (above) from the final review for “Natural Monument” led by Mauricio Pezo and Sofia von Ellrichshausen.

AIA awards the 2019 Topaz Medallion to Toshiko Mori, Robert P. Hubbard Professor in the Practice of Architecture. The award is considered the highest honor given to educators in architecture.

January 2019

Students participate in a range of J-Term workshops, including “Making the Industrial Basket at Three Scales” led by 2019 Loeb Fellow Stephen Burks.

Taking up social and spatial equity in New York, the “Design and the Just City” exhibition opens at AIA’s Center for Architecture. The exhibition debuted in the GSD’s Frances Loeb Library as part of the Spring 2018 exhibitions program.

The Spring 2019 public program is announced, opening with a conversation led by Michael Jakob to introduce the exhibition Mountains and the Rise of Landscape.

February 2019

Dean Mohsen Mostafavi talks John Portman, Atlanta architecture, and Portman’s America with Georgia Public Radio.

Ahead of her lecture at the GSD, architect Beate Hølmebakk discusses her paper projects and rejecting the dominance of user-friendly architecture.

2018 Rouse Visiting Artist Hannah Beachler reflects on her history-making Oscar nomination.

March 2019

The Department of Architecture, and department chair Mark Lee, launch two new lunch talk series: “Books and Looks” and “Five on Five.”

“We were never considered fully human, so why should we care about this crisis?” Philosopher Rosi Braidotti discusses collective positivity in the face of human extinction ahead of her public program lecture.

The Library’s “Multiple Miamis” exhibition presents the city’s multiple personalities, with lessons for cities across the country.

“Streets are what make some cities great, and some cities not so great.” Janette Sadik-Khan addresses the GSD community to discuss her book Streetfight: Handbook for an Urban Revolution.

The 11th annual Platform exhibition, Setting the Table, goes up in the Druker Design Gallery.

The Department of Landscape Architecture announces the 2019 Penny White Project Fund recipients.

April 2019

Sarah Whiting is named the next dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design. A leading scholar, educator, and architect widely respected for her commitment to integrating design theory and practice, Whiting comes to the GSD from Rice University School of Architecture, where she has served as dean since 2010. She previous taught at the GSD early in her career.

The New York Times joins the GSD’s Jesse Keenan for a look at the future of Duluth as a “climigrant friendly city.”

Pioneering conceptual artist Agnes Denes addresses GSD students online. To accompany the piece, Denes created an original object, a six-foot-long scroll of the manifesto she composed in 1970 and which has guided her practice ever since. An artist edition of 1,000 copies of the manifesto designed by Zak Group is offered as a gift to students from Denes.

The Plimpton Professorship of Planning and Urban Economics is made possible by a gift from Samuel Plimpton (MBA ’77, MArch ’80) and his wife, Wendy Shattuck. The position will explore a wide range of urban issues and data, including development, evolving land use patterns and property values, affordability, market and regulatory interactions, open space, consumer behaviors and outcomes, and climate change, and will help inform the decisions of future architects and planners.

The community comes together to celebrate Dean Mostafavi’s 11 years leading the GSD with a “Final Revue.”

May 2019

In celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus School of Design, contributor Charles Shafaieh looks back at the history of Bauhaus performance and the contemporary ways in which GSD students interpreted Oskar Schlemmer works for a Spring 2019 course and event.

Polish architect Aleksandra Jaeschke wins the 2019 Wheelwright Prize. Her proposal, Under Wraps: Architecture and Culture of Greenhouses, focuses on the spatiality of horticultural operations, as well as the interactions between plants and humans across a spectrum of contexts and cultures.

Instigations, speculations, and platforms: Dr. Catherine Ingraham commemorates Dean Mohsen Mostafavi’s lasting contribution to the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

“You belong here.” Naisha Bradley, the GSD’s first Assistant Dean of Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging, shares her vision for community-building.

Class Day speaker Teju Cole discusses the unpredictability and potential of the city ahead of his 2019 address.

The GSD launches the African American Design Nexus (AADN), a virtual collection that illuminates African American architects and designers from various generations, practices, and backgrounds. Its debut represents four years of research and development, a collaboration among Harvard GSD’s African American Student Union (AASU), Harvard GSD dean Mohsen Mostafavi, architect Phil Freelon (Loeb Fellow ’90), and Harvard GSD’s Frances Loeb Library, where AADN is housed.

The GSD awards 364 degrees during Harvard’s 368th Commencement.

Juan Reynoso (MUP/MPH ’20) selected as a 2019 Switzer Fellow

Juan Reynoso (MUP/MPH ’20) has been selected as a 2019 Switzer Fellow , which supports graduate students whose career goals are directed toward environmental improvement and who demonstrate leadership in the field. In addition to being awarded a $15,000 scholarship, Fellows receive leadership training and are matched with past Switzer Fellows based on professional interests.

Reynoso is pursuing Master of Urban Planning and Master of Public Health degrees through the GSD’s joint degree program with the T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Born in California’s agricultural Central Valley and a son of working-class Mexican immigrants, Reynoso has witnessed the health consequences of environmental pollution and injustice. Through his research and advocacy, he hopes to transform cities into health-promoting and sustainable places where all people have an opportunity to thrive. At the GSD, Reynoso is pursuing topics at the intersection of environmental justice, healthy cities, and climate resilience through studios and project-based courses. Prior to the GSD, he worked at the California Endowment, where he helped support organizing and advocacy campaigns to promote healthy, just, and sustainable communities in Southern California. Reynoso is a 2014 honors graduate of Stanford University.

In new report, Jesse Keenan illustrates how the Community Reinvestment Act may reward banks for climate change-minded investments

Harvard Graduate School of Design professor Jesse M. Keenan, alongside co-author Elizabeth Mattiuzzi, has released a new report illustrating how banks could seek Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) credit to make climate-change-minded resilience and adaptation investments in low-to-moderate income communities across the country, signaling a significant move at the federal level toward approaches and perspectives on climate change. Keenan and Mattiuzzi issued the report via the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, where Mattiuzzi is Senior Researcher in Community Development, and their findings have since been picked up by the Wall Street Journal , among others.

“Climate change is already causing disruption to regional economic activity,” write Keenan and Mattiuzzi in the report’s introduction. “Low-to-moderate income populations are highly vulnerable to these impacts, in part, because they often have fewer resources to adapt. The stability and prosperity of local economies in the face of climate change depends on how well the public, private, and civic sectors can come together to respond to the shocks and stresses of climate change.”

Elsewhere, the authors continue, “Community development practitioners, investors and policymakers will find this report useful for sparking new ideas about how to develop partnerships and funding streams for CRA-eligible activities—in both eligible communities and areas within a federal disaster declaration— that will reduce the vulnerability and increase the adaptive capacity of communities to the impacts of climate change.”

Keenan tapped a trio of Harvard GSD students for research and mapping work. Firas Suqi and Samuel Adkisson conducted geospatial data analysis, while Kenner Carmody conducted graphic-design work to capture and illustrate the report’s research and conclusions.

Read the full report via the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, or browse its summary via the Wall Street Journal.

Kuehn Malvezzi on liberating institutional design from all that is “dark, serious, and deeply moral”

This spring, Berlin-based architects Johannes Kuehn, Wilfried Kuehn, and Simona Malvezzi asked Harvard Graduate School of Design students to imagine a new kind of museum for the 21st century, one that acknowledges, even if it rejects, the history and structure of the modern museum. For this, Kuehn Malvezzi’s three principals connected the students with a client of sorts: German collector Julia Stoschek, who has been showing her private collection of performance and time-based art since 2007. Kuehn Malvezzi is not currently working with Stoschek, but the firm renovated a 1907 industrial building in Düsseldorf for part of her collection. Their work for curators, collectors, artists, and art institutions has constituted much of their portfolio since their founding in 2001. Last year, they converted the Prinzessinnenpalais on Berlin’s Unter den Linden Boulevard into a new cultural venue for Deutsche Bank’s considerable art collection. And they won the design competition for Montreal’s redesigned Insectarium, now under construction.

In an introduction to the visiting critics’ recent lecture at the GSD, Mark Lee (MArch ’95), chair of the department of architecture, quoted Viennese essayist Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and related that von Hofmannsthal never felt any conflict “between the dark, serious, deeply moral Teutonic ideal, and the spritely, festive, Latin asceticism” of Vienna at the end of the 19th century. Kuehn Malvezzi’s work similarly grapples with combining playfulness and gravity. Their House of One project—a mosque, synagogue, and church under the same roof—will be built on the historic foundations of one of Berlin’s earliest churches, and they are collaborating with the artist Michael Riedel on a new facade for the Moderne Galerie in Saarbrücken, Germany. We spoke with Wilfried Kuehn about their studio and recent projects.

Why did you choose to focus on museology for your GSD studio?

Should the museum move away from the treasure house and toward a space where it’s not so much the precious object at the center, but rather the experience between visitors? We are now witnessing the fact that more and more private collectors have a lot of important work in storage and we have this huge amount of art that is not public. The class collaborated with collector Julia Stoschek, who owns the largest digital art collection in Germany and is expanding quite rapidly. She collects video and time-based media and shows them in Düsseldorf and Berlin. She’s very interested in the fact that the museum could become a space that is less driven by the objects. We interacted via Skype and then our students visited her in Berlin.

A project like this challenges the whole notion of fundamentalism. It’s risky to be avant-garde and not conform to the anxieties and darkest emotions available.

Wilfried Kuehn on his firm’s latest project, House of One, a mosque, synagogue, and church under one roof.

We challenged the students with conceptual art texts on the role of the museum in society, feminist discourse in the ’60s and ’70s, and art being an experience that is liberating and political, rather than just objectified. They surprised us with spaces we are not accustomed to seeing as art spaces.

The firm has a long tradition of working with artists and within the art world. Is that something you deliberately sought out?

We have been collecting art and working with artists on buildings, so our relations are manifold. I see in art not so much an addition to architecture as a tool and method to think about architecture. We have done many art and building projects where you can’t disentangle the two. This is something that architects don’t usually like to do, because it basically diminishes their role in many eyes. We have never thought about our role like this. We have always thought that the maximum experience is to come together with other arts. We think this is very contemporary once again because of the specialization that took place in the 20th century and the alienation of all the different fields of knowledge that need to be reassembled. And we have a good way forward with art and architecture.

Why do you think your entry for the House of One won the competition?

Our three sacred spaces are all on one level without being the same—they are three individual extruded shapes that come from the historical floor plan. They are equal but not the same. This was what the three clergymen intuitively wanted. The other entries had less of a conceptual approach to the relationship between the three religions.

What have been your conversations around acts of terrorism that happen all too often in religious spaces? How did that play into your design and conversations if at all?

It is a conversation that took place, of course—you cannot avoid it. A project like this challenges the whole notion of fundamentalism. It’s true that you have to provide minimum levels of security in order to make it a public building, but also there is the very strong idea that if we make a building that is high security through and through—like a shelter or bunker—then it would not express the idea of House of One anymore. You have to expose yourself to a certain degree and accept risk. It’s risky to be avant-garde and not conform to the anxieties and darkest emotions available.

Another project, the Insectarium in Montreal, seems very different on the surface than your other work.

The Insectarium is the largest insect museum in North America. It is one of my favorite projects and one that the firm has been working on for many years. They are starting construction now [the museum is currently closed and will reopen in 2021]. It’s a scientific and museological space centered on biodiversity—which is such an important theme. The whole idea of the museum is that architecture and museology meld, which is something very rare. This is why we did it. Our design brings visitors underground and then they emerge into a glass vivarium with live butterflies. Even in the cold Montreal winters you’ll be in a tropical garden. It’s a very experiential “parcours.” The space will develop into an important hub for artistic and scientific encounters.

How would you characterize the core of your work right now?

The question of how society can live together, especially in artificial places such as the metropolis, is our theme now. We have to confront diverse societies in concentrated places. Somehow we have to find a way to live together. In the House of One, for example, each religion maintains their own identity and also reaches out to say, “We want to actively live our differences.” The same openness and interest in the other has to be our way of living in cities. If we don’t win that challenge, it will be very problematic to live on planet Earth, which is too small to avoid each other.

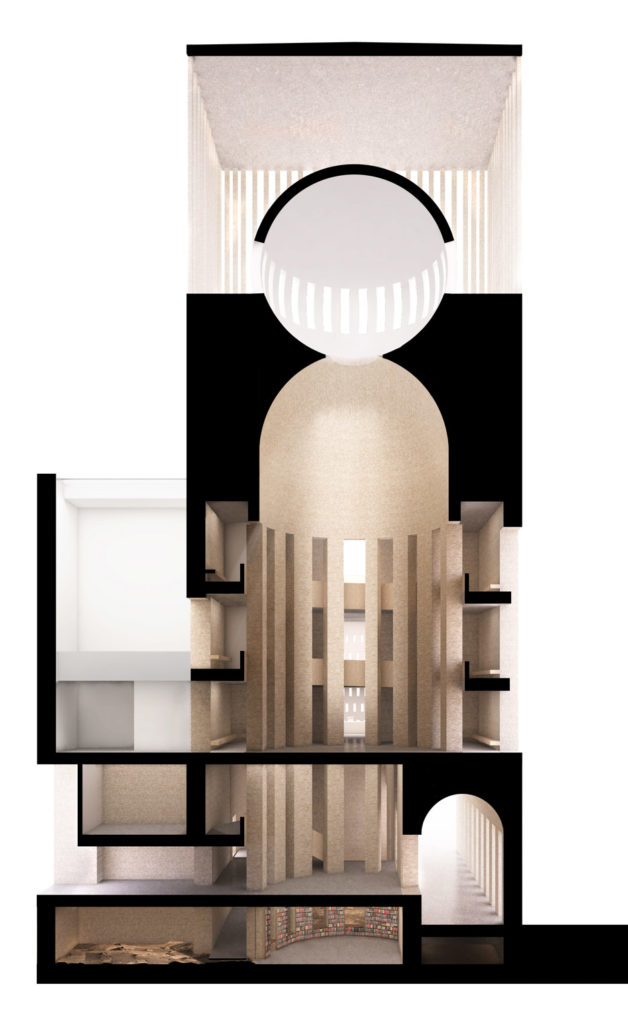

Work in Progress: Xiaotang Tang’s egalitarian museum

Xiaotang Tang (MArch ’20) describes her final project for the option studio “A Novel Museum” led by Johannes Kuehn, Wilfried Kuehn, and Simona Malvezzi, spring 2019.

Work in Progress: Melissa Naranjo’s exploration of regenerative practices in Les Alpilles, France

Melissa Naranjo (MLA ’19) describes her final project for the option studio “RHIZOSPHERE” led by Teresa Gali Izard, fall 2018.

Work in Progress: Aimilios’ bridge

Aimilios Davlantis Lo (MArch ’19) describes his final project for the option studio “The Anamorphic Double: A Bridge for DC,” led by Grace La and James Dallman, spring 2019.