Housing is more than a roof overhead; it shapes our health, our wealth, our life chances, and the invisible lines of who belongs where. The Harvard University Joint Center for Housing Studies sits in the heart of that story. For more than six decades, this research hub—now affiliated with the Graduate School of Design and the Kennedy School—has traced how people live, what housing works and what doesn’t, and when smart policy can widen the circle of opportunity. Its data-rich reports on affordability, homeownership, and neighborhood change help set the agenda for city planners and advocates, lenders and lawmakers alike. And through convenings, fellowships, and cross-sector collaborations, the Center doesn’t just map the housing landscape; it asks us to imagine something better: a future in which decent, stable, affordable homes in thriving communities are a baseline, not a privilege.

Probing the Postwar City

The Center did not begin with a focus on housing. The Joint Center for Urban Studies of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard University, as it was first known, emerged from a larger mid-century effort to make sense of postwar America’s transforming cities—disinvestment, mass migration, rising poverty, and the slow fraying of urban life. A growing consensus held that only interdisciplinary research could grasp these forces and the nationwide urban decline they were fueling.

Harvard and MIT had each established their own centers for this work in the mid-1950s. When both turned to the Ford Foundation for support, the foundation brokered a merger, backing the new entity with grants that, over the next decade, totaled $2.1 million—about $18 million in today’s dollars. Thus, in 1959, the Joint Center for Urban Studies of MIT and Harvard was formally launched with a broad, three-part mission: to conduct research on cities and regions; to connect such research with practice; and to enhance related educational programs at both universities.

The Center’s leadership was deliberately split between Harvard and MIT. Harvard professor of city planning and urban research Martin Meyerson served as founding director, and MIT professor of land economics Lloyd Rodwin chaired the Center’s Faculty Advisory Committee. Both men had logged time in city planning offices and believed that the social sciences were essential to making planning and design responsive to real lives. Together, Meyerson and Rodwin built the Center’s distinctive interdisciplinary approach, drawing on economics, sociology, political science, and other fields to understand how cities actually work.

For its first decade, the Center operated as a kind of urban–intellectual exchange, what a 1964 publication described as “a discoverer and stimulator of talent, a generator of ideas, and a clearinghouse for scholars and funds.” Studies were carried out by Harvard and MIT faculty and graduate students, supported by a small staff tucked into an office on Church Street in Harvard Square. The research agenda was intentionally broad, mirroring its affiliates’ far-flung interests: urban demographic change, transportation systems, the decline of central business districts, even the design of an entirely new city (Ciudad Guayana in Venezuela).

The range of work shows up in the books that emerged from those early years. In the first five alone, the Center produced a remarkable ten books and thirty papers, including Kevin Lynch’s The Image of the City (1960), Nathan Glazer and Daniel P. Moynihan’s Beyond the Melting Pot (1963), Edward C. Banfield and James Q. Wilson’s City Politics (1963), and Charles Abrams’s Man’s Struggle for Shelter in an Urbanizing World (1964). Together, these and other seminal works helped establish the Center as a place where ideas about cities could be tested, contested, and widely disseminated.

In keeping with its mandate, the Center cultivated conversations not only across disciplines but also between researchers and people making decisions on the ground. One such event took place in 1968, when architect J. Max Bond Jr. (AB ’55, MArch ’58) returned to his alma mater to argue for a different kind of urban renewal—one driven by communities themselves rather than by the top-down projects then remaking American downtowns and ousting Black, immigrant, and older residents.

Bond found a receptive audience at the Center. Just a few years earlier, it had published Martin Anderson’s The Federal Bulldozer: A Critical Analysis of Urban Renewal, 1949–1962 , a searing critique of the government’s urban renewal program and its human costs. In 1966, it followed with Urban Renewal: The Record and the Controversy, edited by James Q. Wilson, which offered a measured overview of the policy’s contested benefits and harms.

This focus on people and place—on how lives are shaped by streets, buildings, neighborhoods—ran through the Center’s work. Its “interdisciplinary approach,” as one account put it, “placed the city in a total social and political context and paid close attention to the interaction of people and their environment.” Even before housing became its central analytical focus, the Center was laying the groundwork for its later concentration on the lived experience of home.

Housing Takes the Lead

By the late 1960s, even as former President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs faced restructuring, a national argument persisted over what the government owed its citizens in the way of a decent home and a livable environment. Around the same time, the initial Ford Foundation funding for the Center ceased, forcing a hard look at how the institution would support itself. Under the guidance of labor economist John T. Dunlop, then dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and future US secretary of labor, the Center refocused its attention on “specific urban problems ” in place of the broad general research that characterized its earlier years, starting with housing—a timely subject that sat squarely between theory and practice.

Housing became the lens for a wider set of questions. The Center began to pair policy analysis with research into aspects such on housing markets, construction, and development, and it pulled in voices from outside the university—public officials, private developers, nonprofit advocates—to help shape the work.

To give those partnerships a home—and to shore up its finances—the Center created its Policy Advisory Board (PAB) in 1971, bringing together a coalition of major players from across the housing industry. The original group included about twenty corporate members; today, there are nearly sixty, including companies such as Home Depot , Sherwin-Williams Company , Kohler Co. , and Lennar . In return for financial support, PAB members take part in semiannual meetings where scholars, government officials, and industry leaders discuss emerging trends and concerns in housing. This arrangement is deliberately mutual: it gives firms access to cutting-edge research and candid conversation while providing researchers with insights from key entities involved in housing. In addition, it offered the Center a stable base of funding, financially independent from its parent universities.

In 1985, the Joint Center for Urban Studies made its priorities explicit and renamed itself the Joint Center for Housing Studies. The shift from “urban” to “housing” signaled more than a change in branding. Over the next few years, the Center wound down its doctoral fellowship and executive-education programs, both products of the 1970s, and day-to-day oversight moved from high-level university administrators to the deans of Harvard’s Kennedy School and MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning.

Before long, diverging priorities prompted Harvard and MIT to part ways. By 1989, the Center had become a Harvard institution, jointly anchored in the Kennedy School and the Graduate School of Design (GSD). In the early 1990s, it sat institutionally and physically within the Kennedy School; in 1996, it formally shifted to the GSD and would go on to occupy a series of offices in Harvard Square, where it remains today.

Signature Reports and Expanded Impact

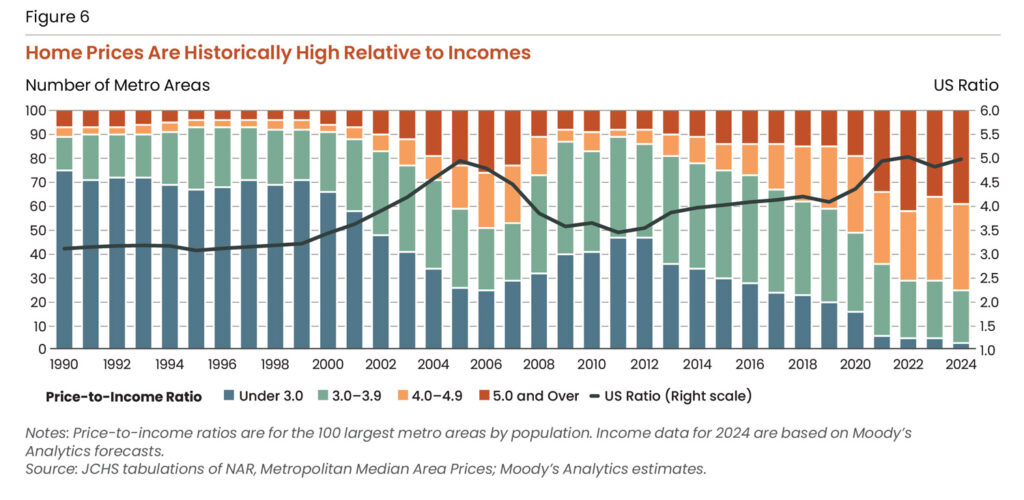

The Center’s visibility took a major leap in 1988 with the debut of its flagship publication, The State of the Nation’s Housing . This annual report—which for many years was supported by the Center’s original funder, the Ford Foundation—tracks recent trends and emerging challenges in US housing markets and forecasts what may lie ahead in the coming year. Drawing on years of survey data from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, population surveys from the Census Bureau, and other sources, the first report opened with a stark verdict on the state of housing in 1988: America was increasingly becoming “a nation of housing haves and have-nots.” Most homeowners were comfortably housed and had built substantial equity in their properties, but that prosperity bore little resemblance to the experience of a growing share of low- and moderate-income households, who faced high costs just to secure minimally adequate homes.

From there, the 1988 report laid out its findings in text and graphics, tracing regional patterns in ownership and renting, cost burdens, housing quality and availability, age and family type, and differences between urban and rural areas. The picture was sobering: homeownership costs were high; ownership rates had fallen, especially for younger households; rents kept climbing and claimed an ever-larger share of household income; only about a quarter of low-income households received public or subsidized assistance; and rising numbers of people were living in substandard housing—or had no housing at all. With this first report, the Center set out “to document these diverse housing problems and provide a sound empirical foundation for the emerging national housing policy debate.”

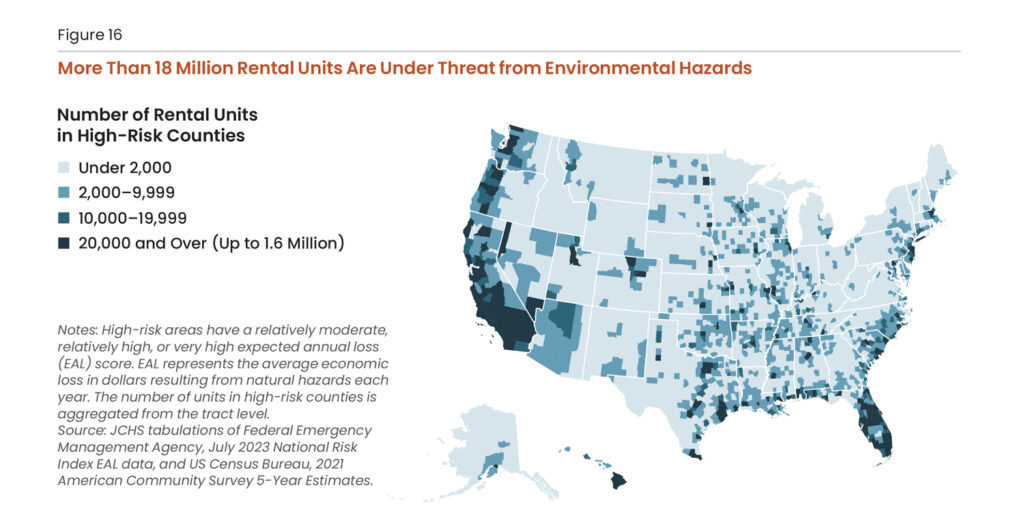

For more than thirty-five years, the Center has continued to publish The State of the Nation’s Housing , cementing its reputation as a go-to source on US housing markets. Over time, it has also carved out more specialized lines of inquiry, producing additional signature reports on specific corners of the housing world. In 1995, responding to a boom in home renovation, the Center launched the Remodeling Futures Program, which tracks trends in the remodeling industry and, beginning in 1999, has issued the biennial Improving America’s Housing report. In recent years, that work has expanded to explore how climate change is reshaping the nation’s existing housing stock. Likewise, the first America’s Rental Housing report appeared in 2006, offering a recurring, in-depth look at the rental market. And in 2022, the Center created the Housing an Aging Society Program, which had released its first report, Housing America’s Older Adults , in 2014.

That same year, the Center launched its newest series, The State of Housing Design , edited by Chris Herbert , managing director of the Joint Center for Housing Studies and lecturer in urban planning and design; Daniel D’Oca (MUP ’02), associate professor in practice of urban planning; and former GSD Druker Fellow Sam Naylor (MAUD ’21). (Recent GSD graduate Aaron Smithson [MArch/MUP ’25] is now working with the editors to produce the second edition, due in 2026). The book-length publication, Herbert notes , leverages the GSD’s design expertise “to call attention to the important role that design can and must play in addressing the housing challenges we face as a nation.” Departing from the primarily quantitative research of the Center’s other reports, The State of Housing Design gathers essays by leading scholars and practitioners—including GSD dean Sarah Whiting, professor Farshid Moussavi, and critic Mimi Zeiger—on how residential design intersects with issues such as sustainability, density, and social cohesion. Taken together, these publications have reshaped not only how we understand housing, but also how the Center positions itself—as a bridge between data and design, policy and practice, and the academy and the wider public.

The Center Today: Connecting with the GSD, the Harvard Community, and Beyond

More than sixty years after its founding, the Center remains committed to advancing rigorous research, mentoring students, and fostering informed public debate on housing. “We understand ourselves to be an intersection between research and the worlds of practice, policy discussions, and encouraging students,” says David Luberoff , the Center’s director of Fellowships and Events.

Where the early Center was essentially a loose constellation of faculty pursuing their own urban-studies projects, today it is a twenty-one-person operation, with full-time researchers, fellows, and administrative staff. Alongside its signature reports and other publications, the Center runs a robust outreach program built around teaching, financial support, and policy engagement. Each year, staff teach two core housing-focused courses cross-listed at the GSD and Kennedy School. The Center also annually funds two to three GSD option studios engaged with housing; roughly twenty summer fellowships for Harvard graduate students working on housing challenges in public, nonprofit, and for-profit settings; and about a dozen additional fellowships and research grants across the university for students focused on housing issues.

The public side of the work is equally expansive. In the past year alone, the Center hosted more than thirty events that drew over 16,000 in-person and online attendees. In 2024–2025, its research was cited in nearly a dozen testimonies before US House and Senate committees, and media outlets across the country referenced its findings more than 20,000 times—a measure of how deeply the Center’s work now shapes housing conversations nationwide.

As an autonomously funded entity affiliated with both the GSD and the Kennedy School, the Center occupies a distinctive niche in Harvard’s ecosystem—financially beholden to neither school yet intent on staying closely linked to each. Herbert, who has led the Center since 2014, puts it this way: “We create collaborations with faculty that define a mutual interest. We may look at it through one lens, they may look through another, but we’re looking at the same thing.”

One of the strongest ties between the Center and the GSD is the Faculty Advisory Committee (FAC), which, in various iterations, has been part of the Center’s governance since its founding in 1959. Today, the FAC includes nine professors—seven from the GSD and two from the Kennedy School. Chaired by D’Oca, the FAC functions as both sounding board and bridge, aligning the Center’s research agenda with the GSD’s pedagogical and design priorities.

A symposium held at Harvard in September 2018, Slums: New Visions for an Enduring Global Phenomenon , stands as a prime example of collaboration between the Center and the GSD. Organized in part by FAC member Rahul Mehrotra (MAUD ’87; John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization), in partnership with the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy , the conference examined the physical, political, and economic realities of slums worldwide. “That was an important touchpoint where we engaged with the GSD on bringing design into conversation with the policy and market analysis that the Center does,” Herbert recalls.

Another noteworthy collaboration followed in 2020, when the Center and the Loeb Fellowship Program cosponsored In Pursuit of Equitable Development: Lessons from Washington, Detroit, and Boston , a half-day event devoted to ensuring that low- and moderate-income households would benefit from new development in their communities.

In the past few years, the Center has looked to tighten its ties with the GSD through new appointments. Herbert references research fellow Susanne Schindler , who joined the Center in 2024. Trained as an architect and a historian of the intersections among architecture, finance, and housing, Schindler “bridges the gap between the design and policy worlds,” he notes. She was instrumental in organizing a spring 2025 half-day event, The Evolving Landscape of Social Housing in New England , and she is currently examining the ways that redevelopment authorities might support the creation of affordable housing.

For Herbert, Schindler’s role reflects a larger ambition. “We look to collaborate across the university, not only with the GSD and the Kennedy School. We’re a center focused on housing, and housing is not a discipline; it’s an object of study. And there are many reasons why every school at Harvard—the law school, business school, and more—should care about housing.”

The Center plans to further magnify its presence by spanning these silos. Over the last year, it has teamed with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Initiative on Health and Homelessness and the HKS Government Performance Lab on multidisciplinary events addressing homelessness. While not always easy to coordinate, “these cross-collaborations bring many benefits,” Herbert acknowledges. “We’ve made progress over the last decade, and there is more to come.” For the Center, collaboration is not an add-on; it is the method by which ideas about housing move into the world.

From its origins as an urban think tank puzzling over postwar cities to its current role as a leading voice on housing markets, policy, and design, the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies has continually adapted to match the scale and urgency of the problems it confronts. Its work has followed people from streets and slums to suburbs and older adult housing, from national statistics to neighborhood-scale interventions, looking to address housing challenges and foster the next generation of housing leaders. As rising inequality, climate change, demographic shifts, and widening affordability gaps reshape notions of home, the Center’s blend of rigorous research, design-minded inquiry, and cross-sector collaboration offers a rare kind of infrastructure: one built not of bricks or beams, but of knowledge, relationships, and the stubborn belief that a decent place to live should be something more than a matter of luck.

*The author thanks Kerry Donahue, Chris Herbert, David Luberoff, and Susanne Schindler for sharing their knowledge about the Center’s history and present-day activities.

Additional Resources

Eugenie Birch, “Making Urban Research Intellectually Respectable: Martin Meyerson and the Joint Center for Urban Studies of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University 1959–1964 ,” Journal of Planning History vol. 10, no. 3 (2011), 219–238.

Peter Ekman, Timing the Future Metropolis: Foresight, Knowledge, and Doubt in America’s Postwar Urbanism (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2024).

The Joint Center for Urban Studies of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, The First Five Years: 1959–1964 (Cambridge, MA:1964).

Christopher Loss, “‘The City of Tomorrow Must Reckon with the Lives and Living Habits or Human Beings’: The Joint Center for Urban Studies Goes to Venezuela, 1957–1969,” Journal of Urban History vol. 47, no. 3 (2021), 623–650.

Christopher Loss, “Remapping the Midcentury Metropolis: The Ford Foundation and the JCUS of MIT and Harvard University ,” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports Online (2014).