Omotara Oluwafemi (MArch ’22): Fostering Black Community and Afrofuturist Architectural Practice

A curious stranger at an airport recently asked Omotara Oluwafemi (MArch I ’22) what she was working on. Oluwafemi surprised herself when she responded, “I’m an architect.” Claiming her identity as an architect and artist took time. Oluwafemi began her undergraduate studies as a math major. “I always liked art, but I thought I couldn’t be an artist or a designer,” she says. A supportive advisor recognized her interest in art history and spatially informed practice, and recommended she take a few architecture studios. She graduated from Amherst with a degree in architectural studies and French, eager to take her work further. When Oluwafemi visited a Harvard Graduate School of Design open house, she was captivated by the diversity and energy of the student work being shown. She was particularly struck by a project that used the chart-topping song “Bad and Boujee” to frame an approach toward luxurious housing for both wealthy and less privileged residents. “All these people were doing such interesting [work],” Oluwafemi says. It solidified her desire to come to the GSD. At the GSD, Oluwafemi became an integral part of the school. Sara Arman (MUP ’22) explains, “Tara makes an intentional effort to build community across Black students and students of color.” As part of the African American Design Nexus (AADN), a collaboration between the African American Student Union and the Frances Loeb Library, Oluwafemi helped launch and cohost The Nexus, a podcast exploring the intersection of design, identity, and practice through conversations with Black designers, writers, and educators. She also contributed to an open-access bibliography to highlight Black practitioners and critically reexamine racial discourses in design and architecture.The GSD is my version of art school. It helped me discover my media and discover my artistic practice.

Omotara Oluwafemi

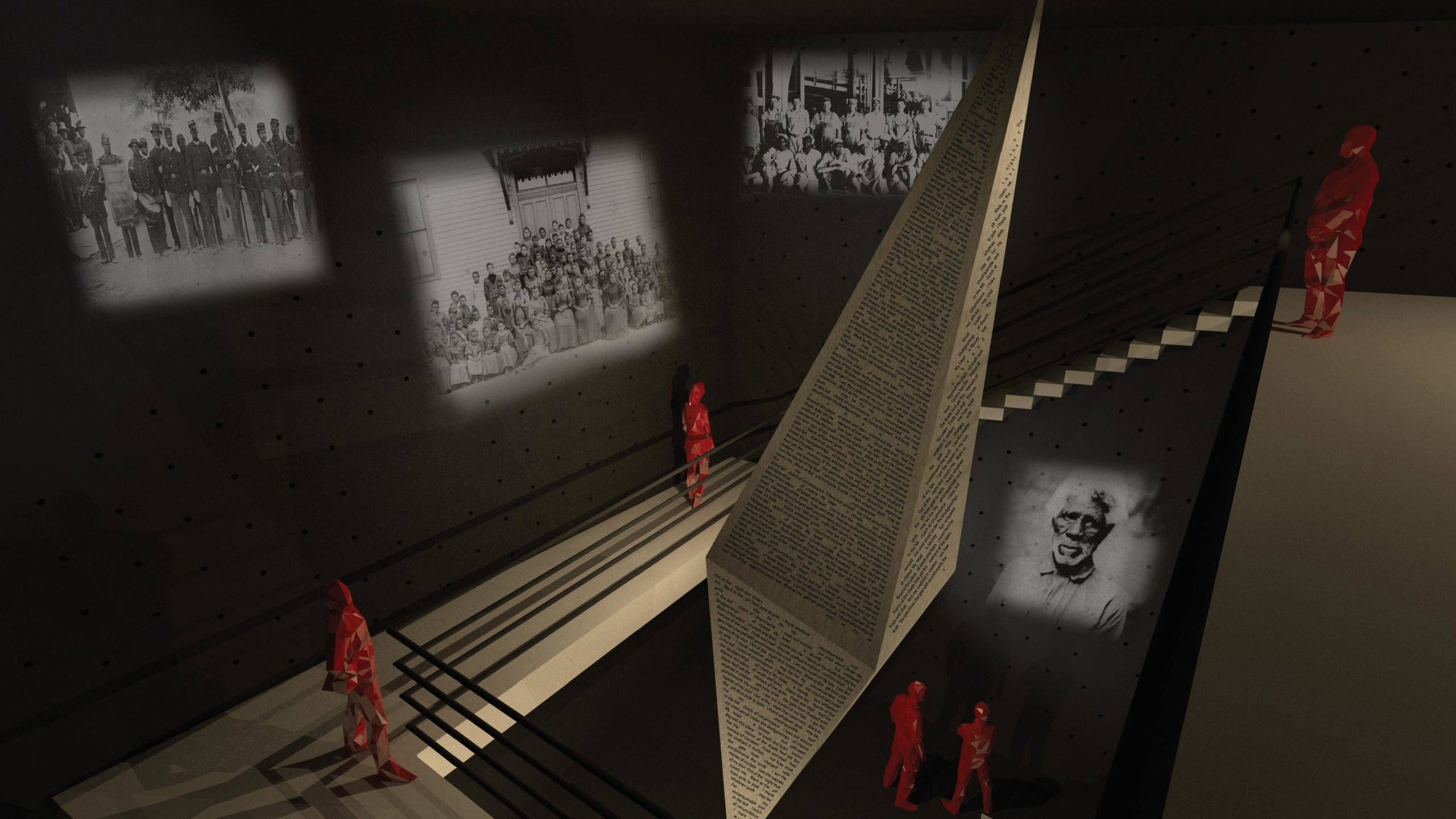

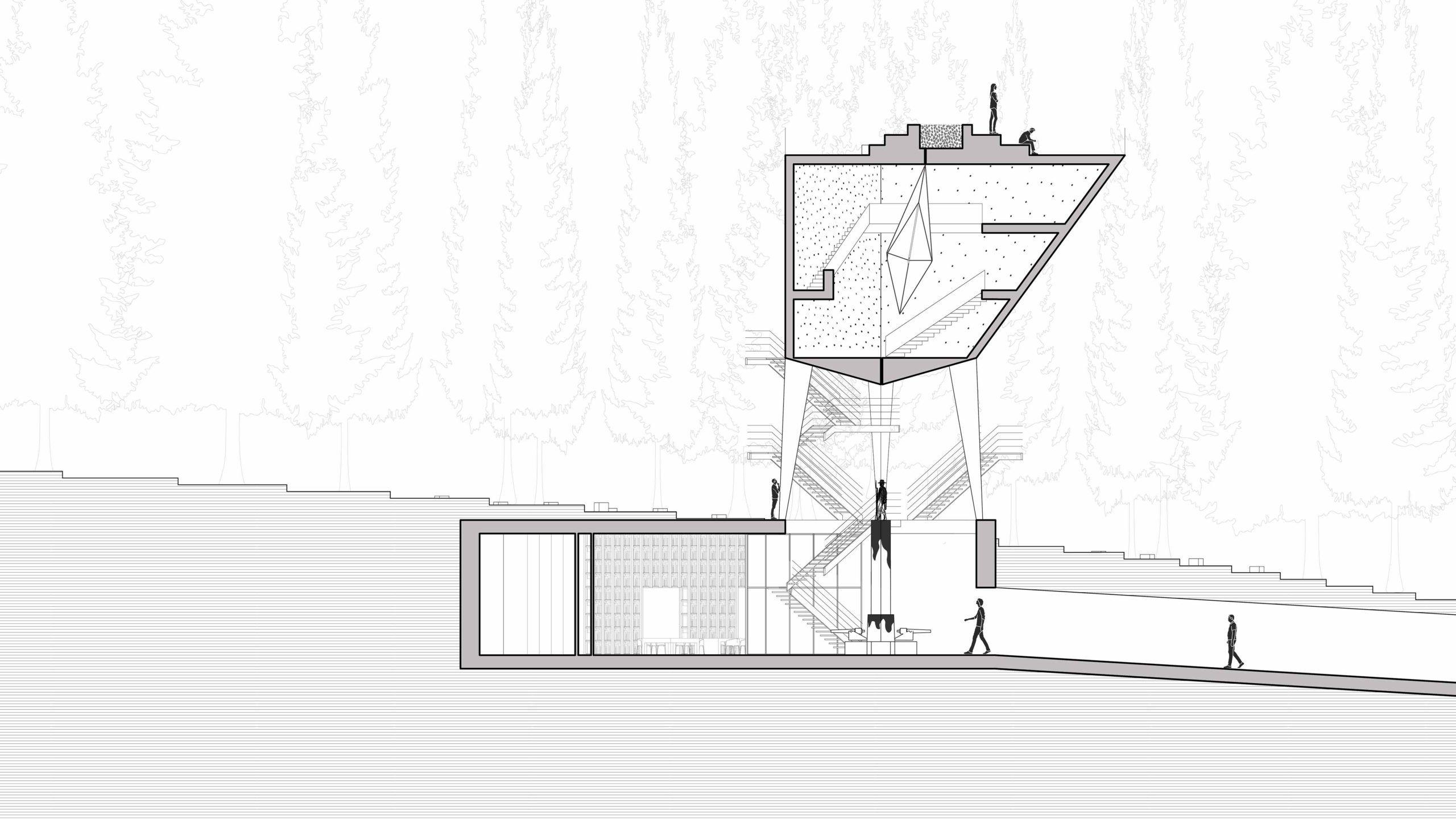

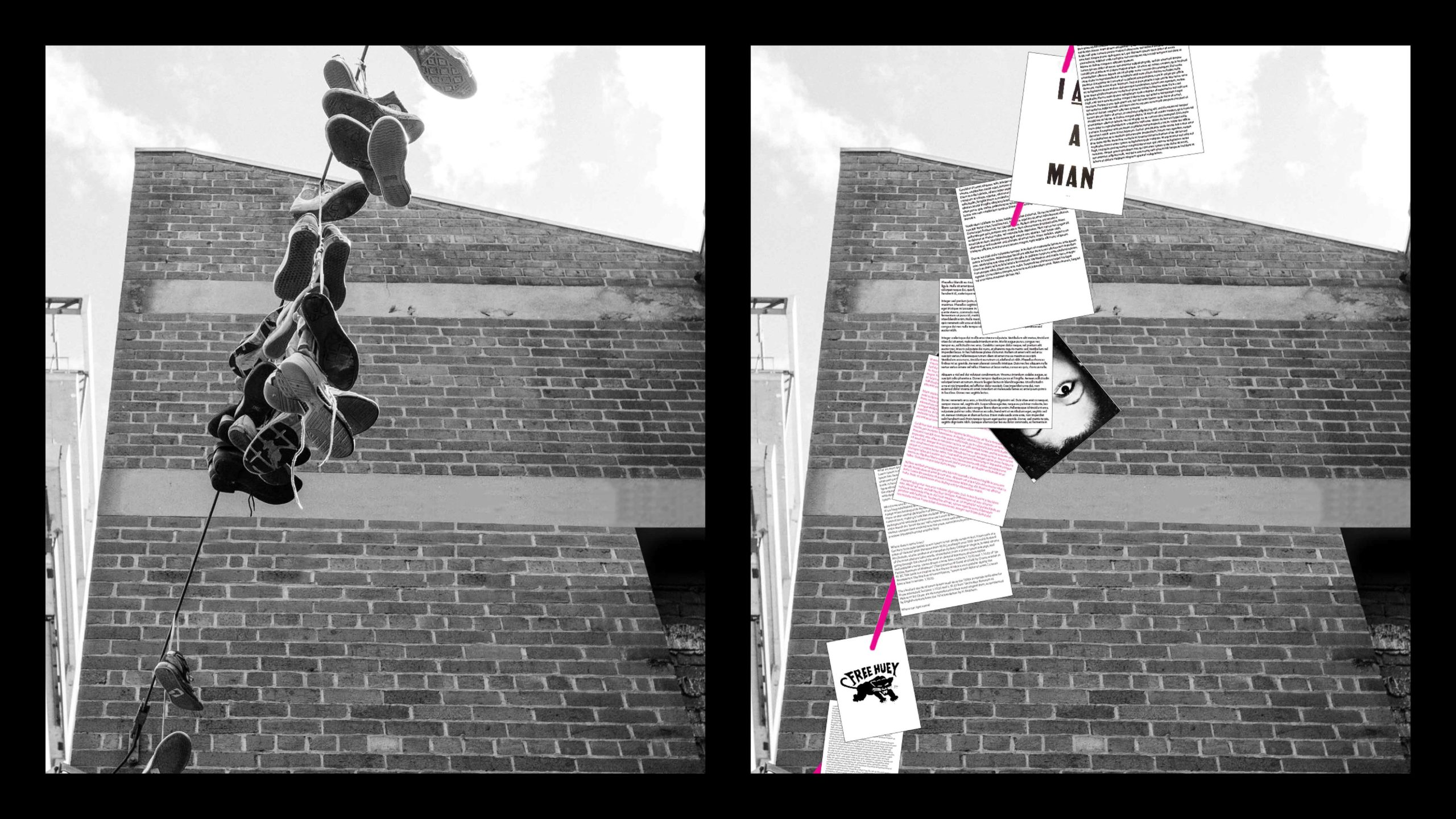

Model from Oluwafemi’s thesis, Mothership. Model labor credits: Kiki Cooper (MLAUD, MDes ’25), Oluwatobiloba Fagbule (MDes ’23), and Sumayyah Raji (MArch I ’23). Photo by Selwyn Quentin Bachus II (MArch II ’22).

Ed Bayes (MDE ’22): Working at the Intersection of Technology, Design, and Policy

Before coming to the GSD, Ed Bayes (MDE ’22) studied law and anthropology and worked in law and public policy in the UK, where he advised the Treasury and the mayor of London on tech, business, and climate policy. Projects included designing the regulatory framework for driverless cars, setting up a “Culture at Risk” office to support grassroots venues at risk of closure, and establishing multibillion-dollar programs to protect the economy from climate and cyber risks. Throughout, Bayes moonlighted as a designer and musician on projects ranging from bands to social enterprises. “I should really have gone to art school,” he jokes. Bayes’s interest in “the intersection between design, engineering, and policy,” as well as a desire to pursue his creative interests full-time, led him to the GSD, where he was supported by a Fulbright scholarship. Once there, Bayes explored how AI could tackle public policy issues, taking graduate seminars in machine learning at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and in climate tech at MIT. The relationships he built with other students were crucial. “It’s rare, even in universities, to bring people with such diverse experiences together to experiment, to fail, to think about ideas that you wouldn’t be able to do in the workplace,” he says.I wasn’t a traditional designer . . . but as I worked through the [MDE] program, my idea of what a designer is really expanded.

Ed Bayes

While Bayes intended to return to the UK and work on Yonder full-time, another collaborative project, from his first semester at the GSD, pushed him in a different direction. In fall 2019, Bayes took Nano Micro Micro, a joint class with the GSD and the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. Bayes worked with Nick Collins (MDE ’21), Anirban Ghosh (MDE ’21), and Milan Wilborn (PhD candidate in materials science & mechanical engineering) to develop applications for an emerging technology that came out of Harvard’s research labs.

The result was Foresight, which uses soft robotics to develop “a wearable navigation device for people who are blind and visually impaired.” Bayes’s grandmother is legally blind, and he and his collaborators thought there was an opportunity to augment existing navigation aids. “We spoke to my grandmother, as well as organizations around Massachusetts, led by people who are blind and visually impaired, to understand whether we could develop something in the area,” Bayes explains. Foresight uses soft robotics and computer vision to provide haptic feedback for users. “Traditional navigation devices like canes are fantastic but don’t let you know if a branch is overhead or a car drives past. Foresight helps you feel the world around you. If a car goes past, Foresight lets you feel it go past. It’s meant to complement, not replace, the cane,” he says. Foresight won the 2020 Harvard President’s Innovation Challenge and sharpened Bayes’s interest in robotics. He later interned at Everyday Robots, a project born from Google’s “moonshot factory,” known as X.

Bayes is now returning to the company as head of policy, where he will use his policy, design, and engineering background to consider questions ranging from trust and safety concerns to the future of work. He is intent on fostering an interdisciplinary, collaborative environment—values core to the GSD experience as well. “Powerful technologies like AI and robotics have great potential to improve humanity, but it requires a considered approach,” Bayes says. Everyday Robots’s approach includes working with artists-in-residence to choreograph human–robot interactions, as well as philosophers and others. “How can we bring designers, policy makers, union leaders, and philosophers into the product development process from the get-go, rather than as an afterthought?” The goal, according to Bayes, is to “shape technology to pursue positive outcomes.”

Bayes’s experiences have given him a unique perspective. He says, “I’ve worked across a lot of disciplines. I’ve studied law, anthropology, design, and engineering; and worked in policy, tech, and the arts.” When he first came to the GSD, Bayes adds, “I wasn’t a traditional designer . . . but as I worked through the program, my idea of what a designer is really expanded.” For Bayes, “Design is a methodology . . . for imagining a desired future state and helping devise [ways] to get there.”

Read more profiles from the GSD Class of 2022.

While Bayes intended to return to the UK and work on Yonder full-time, another collaborative project, from his first semester at the GSD, pushed him in a different direction. In fall 2019, Bayes took Nano Micro Micro, a joint class with the GSD and the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. Bayes worked with Nick Collins (MDE ’21), Anirban Ghosh (MDE ’21), and Milan Wilborn (PhD candidate in materials science & mechanical engineering) to develop applications for an emerging technology that came out of Harvard’s research labs.

The result was Foresight, which uses soft robotics to develop “a wearable navigation device for people who are blind and visually impaired.” Bayes’s grandmother is legally blind, and he and his collaborators thought there was an opportunity to augment existing navigation aids. “We spoke to my grandmother, as well as organizations around Massachusetts, led by people who are blind and visually impaired, to understand whether we could develop something in the area,” Bayes explains. Foresight uses soft robotics and computer vision to provide haptic feedback for users. “Traditional navigation devices like canes are fantastic but don’t let you know if a branch is overhead or a car drives past. Foresight helps you feel the world around you. If a car goes past, Foresight lets you feel it go past. It’s meant to complement, not replace, the cane,” he says. Foresight won the 2020 Harvard President’s Innovation Challenge and sharpened Bayes’s interest in robotics. He later interned at Everyday Robots, a project born from Google’s “moonshot factory,” known as X.

Bayes is now returning to the company as head of policy, where he will use his policy, design, and engineering background to consider questions ranging from trust and safety concerns to the future of work. He is intent on fostering an interdisciplinary, collaborative environment—values core to the GSD experience as well. “Powerful technologies like AI and robotics have great potential to improve humanity, but it requires a considered approach,” Bayes says. Everyday Robots’s approach includes working with artists-in-residence to choreograph human–robot interactions, as well as philosophers and others. “How can we bring designers, policy makers, union leaders, and philosophers into the product development process from the get-go, rather than as an afterthought?” The goal, according to Bayes, is to “shape technology to pursue positive outcomes.”

Bayes’s experiences have given him a unique perspective. He says, “I’ve worked across a lot of disciplines. I’ve studied law, anthropology, design, and engineering; and worked in policy, tech, and the arts.” When he first came to the GSD, Bayes adds, “I wasn’t a traditional designer . . . but as I worked through the program, my idea of what a designer is really expanded.” For Bayes, “Design is a methodology . . . for imagining a desired future state and helping devise [ways] to get there.”

Read more profiles from the GSD Class of 2022. Dianne Lê (MLA ’22): A First-Generation Student Designs Spaces for Recovery, Resilience, and Community-Building

For Dianne Lê (MLA II ’22), design and research is deeply informed by her background. “[I’m] a daughter of war refugees, a first-generation college student, a first-generation graduate student,” she explains. She sees landscape architecture as a way to help people not just survive, but thrive. Lê studied mechanical engineering at Rutgers before realizing that landscape architecture, which seemed “more community and people–centered,” was a more aligned path. She threw herself into her new discipline, winning a research grant that allowed her to visit Berlin to research the relationship between war, migration, landscape, and the built environment. Toward the end of her studies, her mentors encouraged her to pursue landscape architecture in a different academic environment. A summer at the Design Discovery program solidified her desire to come to the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Lê is focused on how landscape architecture interacts with people’s lives and broader institutional concerns. “People create and give meaning to spaces,” she says. “And the spaces and environments in which we grew up also give us a sense of meaning and understanding of who we are.” Lê’s family background—her paternal grandfather was one of the “boat people” who fled Vietnam, and her maternal grandfather a military officer and prisoner of war for 13 years—has made her attentive to refugee and immigrant experiences of landscape as well. “If we come to terms with [the] reality of international conflict and climate crisis,” she says, “we should always expect these perpetual migration and refugee crises to exist. We can’t not center our design projects around people—that needs to be the starting point.”People create and give meaning to spaces. And the spaces and environments in which we grew up also give us a sense of meaning and understanding of who we are.

Dianne Lê

Over 400 stoles (designed by Lê) were ordered by Harvard students for the University’s inaugural First-Gen/Next Gen Graduation Ceremony in 2021. Photo by Steven Gu (MUP ’21).

Sara Arman (MUP ’22): Promoting Health Equity through Community Organizing and Urban Planning

For Sara Arman (MUP ’22), community organizing is essential. When Arman graduated from Tufts with a bachelor in international relations and Middle Eastern studies, she began working with the Women and Public Policy Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. At the same time, she says, “I was looking for ways to get involved with community organizing outside of my work.” Through Arman’s involvement in the Chelsea, Massachusetts, planning board, she heard a number of proposals for urban development and housing projects. Her interest in the field, as well as a conversation with the director of a local housing nonprofit, led her to pursue urban planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. During her studies, Arman also worked as the health equity corps coordinator for GreenRoots, an environmental justice organization in Chelsea, a small, densely populated city with a large low-income immigrant population. It is also her hometown. When she was in high school, GreenRoots helped Arman receive a discounted youth transit pass. She says, “GreenRoots first helped me think about transit through a lens of equity and justice. Providing youth with safe and affordable transit is essential in a dense urban community like Chelsea.”[The] beautiful part of doing community organizing where you grew up is being able to rely on the relationships that you already have.

Sara Arman

Nina Sayles (MUP/ MPH ’22): Making field to table work regionally

Nina Sayles spent five months of COVID isolation at her parents’ place in New Hampshire. An avid gardener, Sayles took advantage of the time to expand their garden — perhaps, she admits, a bit more than they need, now that she’s back on campus. After she graduates in May, Sayles wants to expand the garden for the rest of us, too. Sayles has been exploring the intersection of community health and agriculture in a dual-degree program at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Graduate School of Design. While the modern industrial food system has worked wonders feeding the world, its flaws have also become apparent: excess resource use, narrowing of varieties, foods — both fresh and processed — selected for shelf life and stability during transport rather than taste and nutrition. Continue reading Sayles’s profile on the Harvard Gazette website. Read more profiles from the GSD Class of 2022.Students in Dialogue: A conversation with MArch II candidate Selwyn Bachus

What is it like to be a Master in Architecture II student at the Harvard Graduate School of Design? In this series of candid conversations between students, Tomi Laja (MArch II ’22) speaks with Selwyn Bachus (MArch II ’22) about his decision to attend the GSD, cultivating Black space through design, and post-graduate aspirations.What were you doing before you came to the GSD?

I graduated from college in May of 2019. And I didn’t know where I wanted to go to grad school, if I wanted to work, or what I was going to do. So I spent a year as an alumni volunteer at my high school in Omaha. I worked at the school for almost 60 hours a week with the robotics club, coaching football, and helping out with extracurricular activities—like keeping the gym open at night so that students would have somewhere to go. I used this experience as an opportunity to develop my own methodology of working with students.What led to your decision to attend the GSD?

The reason I wanted to begin post-professional education was my desire to teach. As an undergraduate, I didn’t have any professors of color, and I only had one professor who was a female. So I saw a severe lack of representation in my own education, and moving forward I want to play a role in changing that. A lot of my professors in my undergraduate career came from the GSD, and the GSD has a reputation for producing great teachers who really understand and have a command of pedagogy.

Image by Selwyn Bachus for Cancel Architecture [M2]

How was your Open House experience—especially since it was virtual?

Open House was interesting, to say the least: I had never taken an online class before starting at the GSD last semester, and the simple thought of a virtual open house and virtual school was terrifying to me. But I appreciated the breaking down of the Open House into a week-long experience, as opposed to a one-day sprint. The multiple avenues of learning about the school throughout the Open House week was really helpful because I was able to talk to a lot of people. The thing that really solidified my choice to come to the GSD was a student-led virtual event I attended during Open House with other prospective and current students. It was so fun because people were being themselves, listening to music, and having a great time in the zoom chat. The students were really engaged, even in the virtual sphere.Graduate studies have expanded my own conception of what architecture is, what architecture can be, and what architecture can do. And I think that that’s pretty powerful.

I also remember the excitement from Open House. The students’ talent and passion have been such a big part of my graduate school experience. Was there a specific subject you knew you wanted to study before attending?

Yes—my entire statement for my application essay was about the making of Black space. I poured my soul into expressing my desire to create Black space and to understand what it means to craft those spaces. And it hasn’t changed at all. It’s only been amplified from my studios with Toshiko Mori, Scott Cohen, and Bryan Lee. The Master of Architecture II program gave me the opportunity to craft my own path and decide what I want to do and how I want to go about it. During my first semester, I took Toshiko Mori’s “House of Our Time” module studio and then Preston Scott Cohen’s “Cancel Architecture” for my second module in the first semester. Both allowed me to further my investigation of Black space.

Image by Selwyn Bachus for Cancel Architecture [M2]

Since your primary goal is to teach after your graduate studies, have you had a teaching assistantship during your first year at the GSD?

Yes—I asked Scott if I could be the TA for “Cancel Architecture.” Because I knew what I wanted to do, it was easy for me to identify the courses I wanted to be involved in. Not only was I able to engage in further defining what Black space is for me, I was also able to gain pedagogical experience. So the GSD has offered me the ability to combine the two.Do you plan to do a thesis at the end of your master’s degree?

I want my thesis to be in line with what I wrote in my application essay and the conversations I have had in my first semester and a half at the GSD. My project is going to be about creating and fostering Black spaces in the city of Omaha, while highlighting the social, historical, and physical violence enacted upon Black people in the city. One hundred years ago, a black man was lynched for a crime that he did not commit. This past summer, a young man was shot during George Floyd protests. The deaths of these two men are separated by six blocks, on the same street. I would like to work on a thesis that confronts this history and exposes that it is ingrained in the physical fabric of the city and that brings people into direct contact with the history of spatial violence, physical violence, and socio-historic violence.

Image by Selwyn Bachus for Black New Deal [M1]

Have you taken any courses outside of the GSD yet?

I haven’t taken any courses outside of the GSD yet. I’m interested in taking courses at Harvard Divinity School to tie together spirituality, architecture, and Blackness because I feel like they are primordially intertwined.Do you have a favorite course so far, and if so what did you find interesting or challenging about it?

All of my studios have been so powerful for my own maturation and my thinking. If I have to choose a favorite, I would exclude all the studios since I cannot pick one over the other. So actually my favorite class is one I am taking this semester: Jorge Silvetti’s “Regarding an Archive.” Rodolfo Machado and Jorge Silvetti are donating their entire archive of works to the GSD. As Silvetti’s final pedagogical exercise and teaching experience, he is offering a course that is a retrospective and a reflection on Machado Silvetti’s work over the decades. It is a deeper reading of their archive, a sort of biography. To have the opportunity to hear the why—why make certain moves in architecture, formally, programmatically, stylistically—from such a revered icon in modern and postmodern contemporary design is eye opening and greatly appreciated. It’s interesting to witness an architect reflect critically on his career. In the long run, it will be helpful not only for myself, but also for the other students in the course, to have witnessed that sort of reckoning with one’s self in order to define who we want to be moving forward as architects.How have you grown so far through your graduate studies at the GSD?

As far as personal development, I would say that I’m not the same right now as I was six weeks into the semester or at the beginning of this semester. Graduate studies have expanded my own conception of what architecture is, what architecture can be, and what architecture can do. And I think that that’s pretty powerful. I think as architects, our strongest trait is our ability to dream. I believe it is our superpower actually, to dream of a better world and of better spaces. My time at the GSD has allowed me to dream, which I am thankful for. “Students in Dialogue” is a series of candid conversations between students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.Interviewer Tomi Laja is currently a Master in Architecture II degree candidate at the GSD and Editorial Assistant with Harvard Design Magazine. Her interests include research-based architectural design, exhibition, and writing. Her independent research includes afro-futurist and eco-feminist perspectives as they relate to agency, consciousness, and the built environment.Students in Dialogue: A conversation with MDE candidate Nupur Gurjar

Nupur Gurjar. Portrait by Chidy Wayne.

What drew you to the GSD and the Master of Design Engineering program?

After finishing my architecture undergrad degree, I stepped into design roles that were a bit unconventional, but ones that enabled me to explore critical design thinking. The Master of Design Engineering program is about applying design thinking into various fields, not necessarily just for architecture or the built environment but for design in a broad sense. The approach applies systems of thinking across cultural experience, collaboration with teams, learning by doing. The students in my cohort are not all from a design background; in fact, their backgrounds range from engineering to economics. Here, design means problem-solving and using critical thinking, innovative ideas, and principles of design to apply the right kind of approach to a project. Within MDE, I can bring in skills that are creative, critical, analytical, technical, and non-technical, and this gives me the freedom and flexibility to wear different hats and enter career paths as a designer who has the ability to understand problems and people.

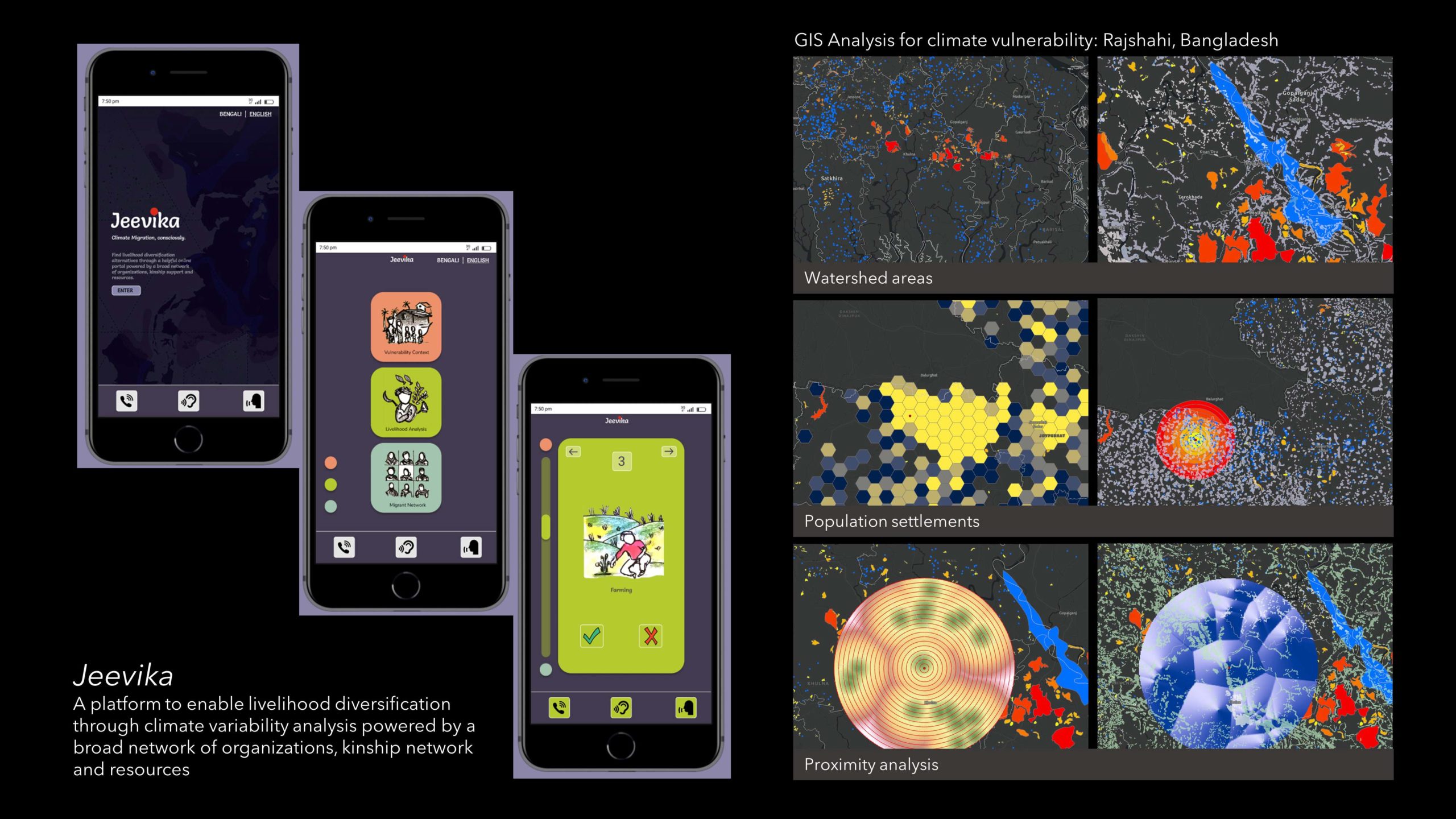

Images by Nupur Gurjar. MDE Independent Design Engineering Project. A systemic perspective to Climate Migration in Bangladesh: Visual Interaction Design

I really like what you’re saying about this multi-dimensional view on both what design is, but also your role as a designer. What was your experience before entering the program?

I’m from Bangalore, India, and in my final year studying architecture, I decided to intern in Mumbai. That internship really gave me a deeper idea of my passion, likes, and dislikes. At that point, large-scale commercial architecture jobs stopped holding their appeal to me, so I started exploring. I am also a performer and have been trained in classical dance and music. I entered the field of production design as a set designer for the media industry. I saw my training as a designer and a performer come together. Being a set designer was like looking at design and interiors through the lens of a camera that stretched beyond my drawings and 3D visualizations. I worked on a music video for Puma which was really colorful and cultural and for a web series with Amazon Prime. My second year of work experience was as a design research assistant in the city of Ahmedabad at CEPT University, Design Innovation and Craft Research Institute. I was part of a number of ethnographic field studies on vernacular furniture in northwest India. That opened doors to my interests in design research and engaging in a methodology to understand the influence of furniture design that has seamlessly integrated into the traditions, space, and life in communities.You really took an opportunity to explore your path as a designer whether it was through architecture, set design, or research. Was a portfolio required for the MDE program?

Yes: Design Engineering accepts candidates from all different backgrounds, so the content of portfolios ranges. Some students have architecture projects, and others might emphasize research/ policy studies/ economics/ science and technology, etc. in their portfolio. The MDE program is very broad, and I tried to connect my diverse set of experiences and understanding of design to the vision of this program. When submitting your portfolio, I would recommend that you show your process of learning, discovering, and thinking that led to certain decisions; include low-fidelity prototypes, sketches, and mock-ups for products/ services or experiences designed. This could depend on the kind of project being showcased, but ultimately, it is important to include why a certain intervention matters and what value or impact it has on society.Within MDE, I can bring in skills that are creative, critical, analytical, technical, and non-technical, and this gives me the freedom and flexibility to wear different hats and enter career paths as a designer who has the ability to understand problems and people.

Was there a specific subject that you wanted to study when entering the GSD?

I looked forward to studying at the GSD, and to be frank, I did not have a specific focus at first. It was my first time traveling internationally, and I was looking forward to absorbing a new outlook on my student life experience. I remember my admiration while walking the halls of the GSD with professionals that I’d read about in publications. That was truly exciting for me. I wanted to immerse myself in experiences that would help me grow as a designer, within the conventional boundaries of where designers thrive but also beyond it, at the intersection of other emerging fields and technologies.How is the MDE program structured, and what projects excited you?

The MDE program is semi-structured with some mandatory courses but also a considerable amount of flexibility. We have Design studios in our first year with exposure to a system of working in cross-functional teams on quick design sprints as well as longer projects on Product, Service, Experience design with a hint of Data visualization and UI/UX design based on project demands along different themes that is set for every MDE incoming cohort. The first year can be exhausting, but it paves the way for our year-long Independent Design Engineering Project (IDEP) in the second year. I am working on designing an experiential service design intervention on climate migration in Bangladesh for vulnerable communities impacted by gradual climate events.Have you taken any courses outside of the GSD?

Last semester I took “Conducting Negotiation on the Frontlines” at the Kennedy School of Government. It taught me about negotiation in a relational environment. It was an amazing course, and I think I was the only design school student. The experiential course design enabled the intersection of design thinking in humanitarian response. I met a lot of new people and made a lot of new friends. Another course I cherished was at Harvard Law School, a place where I had never imagined design to be applicable. My interest in climate design led me into a project where we were looking at reducing artificial synthetic nitrogen fertilizers for farmers, and we were even able to visit Wisconsin for our research. I enjoyed the challenge of addressing a complex challenge for the farmers to enhance or maintain their yield while reducing the fertilizer application through a tool kit designed for fertilizer calculations and modeling.

Nupur studying outside in the fall of 2020.

That’s exciting. I’ve taken some courses outside of the GSD as well, focusing on Gender Studies and Curatorial Studies. I’ve been thinking of the Law School but find myself feeling intimidated: you’ve inspired me to go for it.

It is. It’s just amazing. Again, you meet a whole new bunch of people that you would not typically meet.Do you have any specific advice for international students about life on campus and careers after MDE?

In terms of campus life, Harvard has endless opportunities, including incredible research and innovation labs. And relationships with the amazing faculty are invaluable. Living abroad can be expensive, but there are some great research and work opportunities on-campus for employment as an international student. As for career paths after MDE, there is no single answer—it depends on your background, project experiences, or even entirely new skill sets that are learned here which may lead to a whole new career pathway. MDE students have typically taken up jobs as product designers, UI/UX designers, system engineers, consultants, strategists, or even started their own venture post-graduation. Our path will be less about the job title and more about what we can bring in terms of design and problem-solving.I’d love to hear about organizations you’ve been involved with at Harvard.

Firstly, I would like to tell any future student to balance your school time with your passions and interests beyond the classroom. Events happen on a daily basis in the form of conferences, lectures, social networking, and more. It can be overwhelming, but it is important to keep reminding yourself to prioritize and think of the value you seek during your time here. In March 2020, I participated in the Harvard Circular Economy Symposium with students from the GSD, the Business School, and the Kennedy School; we organized the inaugural conference and worked on building an exposure and awareness of what “circular economy” means as a concept. I am still actively a part of that group. I also was a Community Service Fellow at the GSD last summer (2020). It is a fellowship for students at the GSD to work on a project with a nonprofit or a public organization in the US or abroad. I worked with Boston organizations on designing a Green Innovation district strategy to strengthen climate resiliency. For the term 2020-21, I was elected as the Student Groups chair at the Student Forum GSD. I’m the liaison for the approximately 40 student groups at the GSD. We also have meetings with the dean and learn about the administrative side of the school. Being on the leadership side has always been very enriching for me. I am also involved with the GSD Alumni Council’s Design Impact event series. I curated and moderated a panel in the Design Impact for South Asia event in February 2021 on climate migration, and I am using this opportunity to broaden my own passion and interest for climate migration in line with my thesis. I was also involved with the India Conference at Harvard, 2021 which led to some valuable connections to meet professionals working in this area. It is the largest student-led conference in the US, and is organized by students of the Business School and Kennedy School every year. Finding ways to engage in programs outside of my coursework that complement my scholarship has been a real highlight of my time in the MDE program, and something I would recommend to any incoming student. “Students in Dialogue” is a series of candid conversations between students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Interviewer Tomi Laja is currently a Master in Architecture II degree candidate at the GSD and Editorial Assistant with Harvard Design Magazine. Her interests include research-based architectural design, exhibition, and writing. Her independent research includes afro-futurist and eco-feminist perspectives as they relate to agency, consciousness, and the built environment.Students in Dialogue: A conversation with MLA candidate Xinyi Chen

Xinyi Chen. Portrait by Chidy Wayne.

What brought you to the GSD and what were you doing before coming here?

I graduated one year early from Penn State, and decided on a gap year before graduate studies. During the first half of the year, I was preparing my graduate school applications and then I went to Copenhagen to intern with Bjarke Ingels Group. What attracted me to the GSD is its multidisciplinary approach to education, which provides a great platform for designers with different backgrounds to connect.What did you study at Penn State?

Landscape architecture, so the same field as I am studying now.Is a portfolio required in the application for a Master’s in Landscape Architecture?

We do have a portfolio requirement, and I think the portfolio plays an important part in an application because it shows the skill of storytelling, the style of your diagrams, and your talent for design.

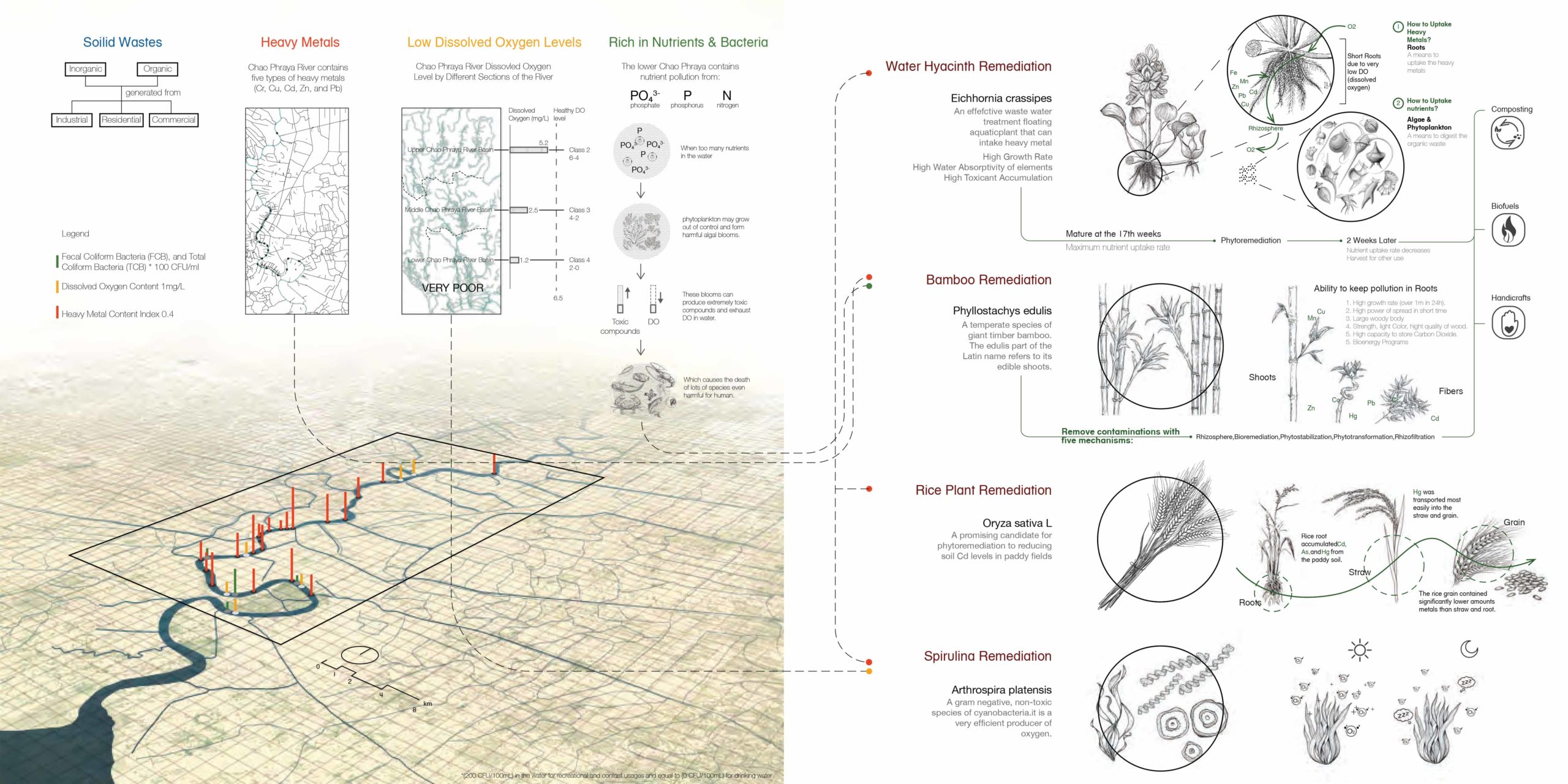

Images by Xinyi Chen for Thailand Remade: Lower Chao Phraya Flood Plain, Pathum Thani, and the Technological Imagination

Was there a moment when you knew the GSD was where you wanted to continue your studies?

I really wanted to attend the open house, but at that time I was in Copenhagen for my internship. I did visit the GSD while I was at Penn State, though, and the GSD was always my first choice. The moment I received the offer, I knew that I would be a student here for sure. I also received financial aid that further assured me.Was there a specific topic or subject you wanted to study?

Initially I was interested in climate change, because at the GSD we often discuss how landscape architects play a role in alleviating the effects of climate change. Then, I took a seminar with Martha Schwartz during my second semester where we learned about the root cause of climate change and some mitigation methods. That furthered my interest. To what extent can we mitigate climate change and what actions should be in place are big questions that need to be answered.

Images by Xinyi Chen for Washington Common – Martin Luther King, Jr., Upended [M1]

Do you have a favorite course? What has been exciting or challenging with your studies?

I do have a favorite course: “Paper or Plastic: Reinventing Shelf Life in the Supermarket Landscape” with instructors Teman and Teran Evans, which I took in the fall of 2020. In that course, we worked as a team of eight to rebrand a very common product: Dial antibacterial soap. We redesigned the logo, the tech line packaging, looked at the target consumer, etc. I think the most challenging part was working in the virtual environment as a large group. It was also difficult to produce a 3D print product when Gund Hall was not open. Fortunately, even though we were from different programs, schools, and had distinct schedules, we were always punctual and efficient . . . most of the time. We were also very satisfied with our end product and presentation. A critic even offered us an opportunity to propose our ideas to Dial. This semester we are pushing our idea forward and sharing the work with Harvard’s Office of Technology Development, which helps protect intellectual property, in case we want to turn it into a business.It seems like you enjoyed learning about product design. At the beginning of your graduate work you were interested in climate change: is that still your focus?

I’m still focused on climate change. I’m taking a studio related to the topic with Chris Reed this semester. Although I enjoyed exploring product design and rebranding, mostly because of the course I just mentioned. I’m considering both options when I think about my career.Everyone at the GSD is like a drop of water converging into Gund Hall, which is like an ocean generously absorbing provocative thoughts, debates, and even conflicts. I would like to be that drop of water pushing forward the waves of landscape architecture.

Are you working on a thesis?

I’m not working on a thesis because I prefer to take more classes from different schools and programs to explore many fields of interest.Have you taken courses outside of the GSD?

I took a course at the Harvard Kennedy School called the Science of Behavior Change taught by Todd Rogers. The primary focus is on how people’s tendency to make decisions deviates from optimal choices, as well as how the consequences of such deviations can inform the design and the development of welfare-enhancing interventions. In short, we were studying how people make decisions and interventions to nudge people into making ideal choices. My team was working to devise an intervention based on behavioral science to reduce the current racial disparity in police issuing traffic tickets to drivers in Suffolk County, New York. I am also taking another course this semester at MIT. So there are lots of opportunities both within the GSD and outside of the GSD.Could you talk a little bit about the community culture at the GSD? I know you’ve been in-person and virtually: have there been any special moments or qualities that you would like to share?

I would say that the GSD is a very inclusive community and everyone can find a spot where they belong. There are many clubs you can join: China GSD, Womxn in Design, Career in Design, GSBee, GSTea, and RED (Real Estate Development Club), just to name a few. During the Mid-Autumn Festival, which is a traditional Chinese festival, I received a mooncake from China GSD. There is also always a spot in the trays or the library and many activities and lectures that students can participate in.

Studio trip for Thailand Remade: Lower Chao Phraya Flood Plain, Pathum Thani, and the Technological Imagination

You were part of the GSD’s first studio in Thailand. Were you able to travel there?

We were very lucky because we traveled early—right before the outbreak of the pandemic. We collaborated with the local community and investigated the water quality conditions there. We were working in pairs to devise a purifying system locally in Thailand because the Chao Phraya River is highly polluted. Our designs are trying to use vegetation as a medium to help purify the area over time.

Class photo for Thailand Remade: Lower Chao Phraya Flood Plain, Pathum Thani, and the Technological Imagination.

Reflecting on your time here, how have you grown as a student and designer since attending the GSD?

The GSD has offered me many opportunities to explore my interests. Not only have I grown as a designer, but the most important quality I’ve learned is how to work with a team. This is something that I rarely did as an undergraduate—my studio work typically consisted of individual projects. After graduation, teaching is one of my first choices, and the GSD has offered me a lot of resources that I can use to facilitate and go forward with this goal. I have been provided with a great platform that allows designers with different backgrounds to communicate and design together. Everyone at the GSD is like a drop of water converging into Gund Hall, which is like an ocean generously absorbing provocative thoughts, debates, and even conflicts. I would like to be that drop of water pushing forward the waves of landscape architecture. “Students in Dialogue” is a series of candid conversations between students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Interviewer Tomi Laja is currently a Master in Architecture II degree candidate at the GSD and Editorial Assistant with Harvard Design Magazine. Her interests include research-based architectural design, exhibition, and writing. Her independent research includes afro-futurist and eco-feminist perspectives as they relate to agency, consciousness, and the built environment.In Cotton Kingdom, Now, Sara Zewde retraces Frederick Law Olmsted’s route through the Southern states

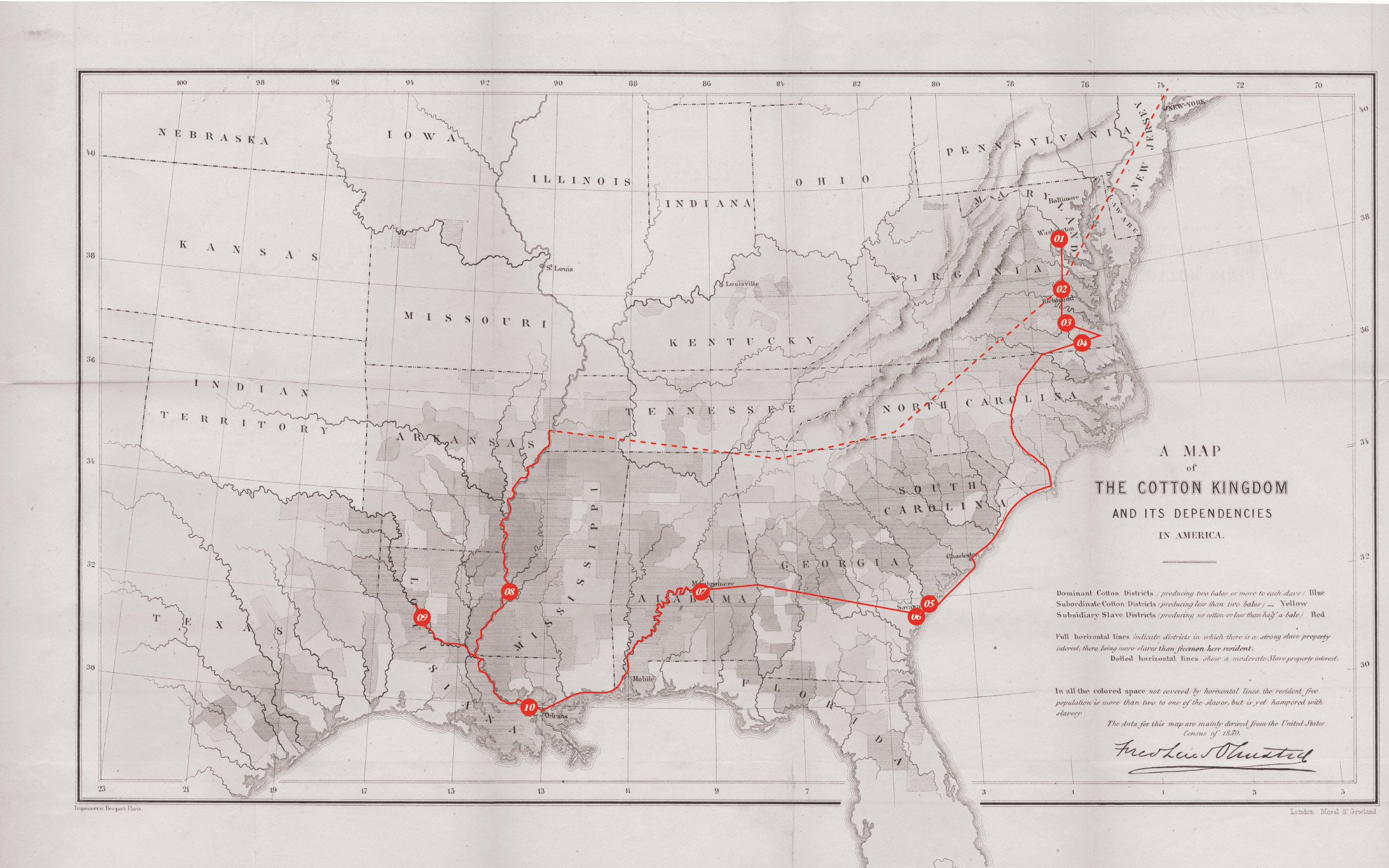

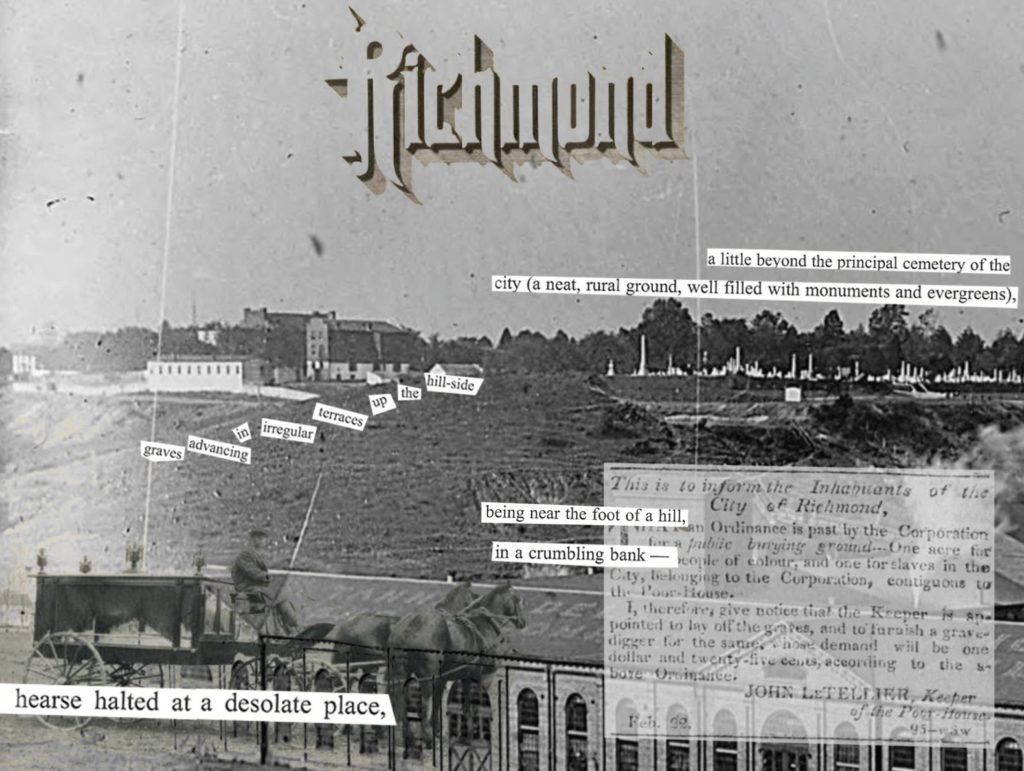

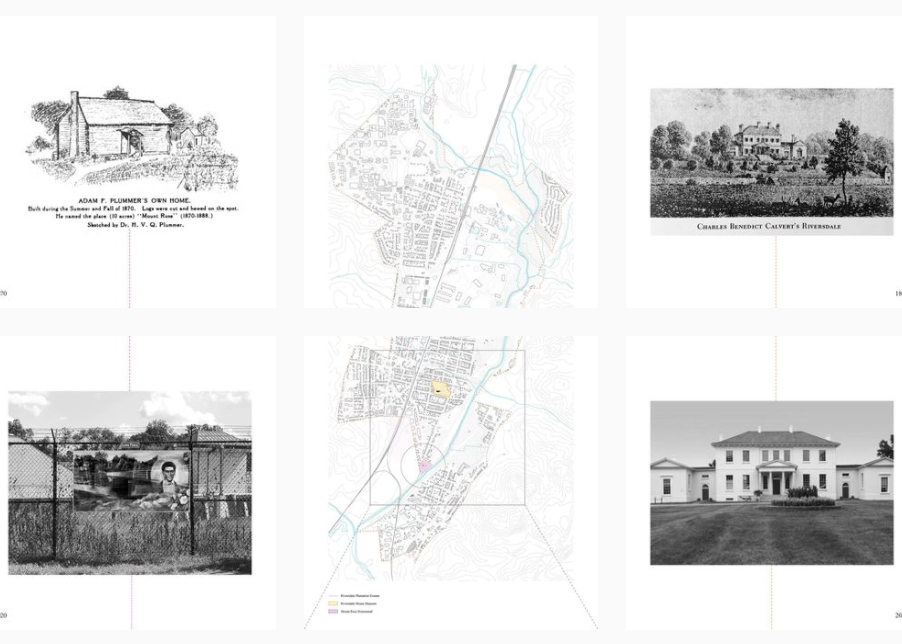

“The mountain ranges, the valleys, and the great waters of America, all trend north and south, not east and west,” says Frederick Law Olmsted in the introduction to his 1861 book, Journeys and Explorations in the Cotton Kingdom. “An arbitrary political line may divide the north part from the south part, but there is no such line in nature—there can be none socially.” Long before Olmsted mulled over the landscape of Central Park or pondered the potential of shared green space in the urban fabric of American cities, the father of modern landscape architecture was a curious 30-year-old unsure of his purpose. In 1852, following travels from China to England, where he came to understand the complex relationship between landscape and class, power, ecology, and identity, Olmsted was dispatched to the Southern slave states by the New York Times. For the next two years, against the volatile backdrop of the Compromise of 1850—five bills that served as a temporary truce on slavery and territorial expansion after the Mexican-American War—Olmsted reported on the cultural and environmental qualities of the region in scintillating detail. He traversed the networked web of slavery, society, and economy, and unpicked the myriad ways that these forces played out in the sweeping landscapes of the American South. Across two trips, Olmsted visited tobacco plantations in Virginia and the Great Dismal Swamp of North Carolina. He happened upon slave burial grounds in Savannah, Georgia and journeyed the Emigrant Road of East Texas to the borderlands separating the US from Mexico. He witnessed Black burials outpouring with song and emotion; he also saw the hanging of an enslaved woman who had killed her own child, for whom she feared a life of unending suffering. He spoke to both enslaved people and slave owners, abolitionists running free-labor plantations and racist drunks in small-town bars to probe the heart of the South’s cotton complex: to not only describe the region, but to carve out a space for a more nuanced understanding of the South in order to find common ground and a path to abolition. Olmsted remained committed to his research on the Cotton Kingdom throughout his career as a landscape architect, even stepping down from his demanding position as superintendent of Central Park to rewrite portions of the text ahead of its 1861 publication. His research methodology, visceral narration, and sensitivity toward the South and its many discrete agents remain powerful tools for reading the built landscapes of past and present. And this proposition is precisely where Sara Zewde’s Fall 2020 seminar “Cotton Kingdom, Now,” begins.

Collage by Charles Burke and Caroline Craddock depicting historic conditions of the Second African Burial Ground as described by Olmsted

Google Maps pinpoint for the Mount Rose Homestead in Maryland by Rachel Coulomb and Cynthia Deng

Instagram for Mount Rose Homestead by Rachel Coulomb and Cynthia Deng

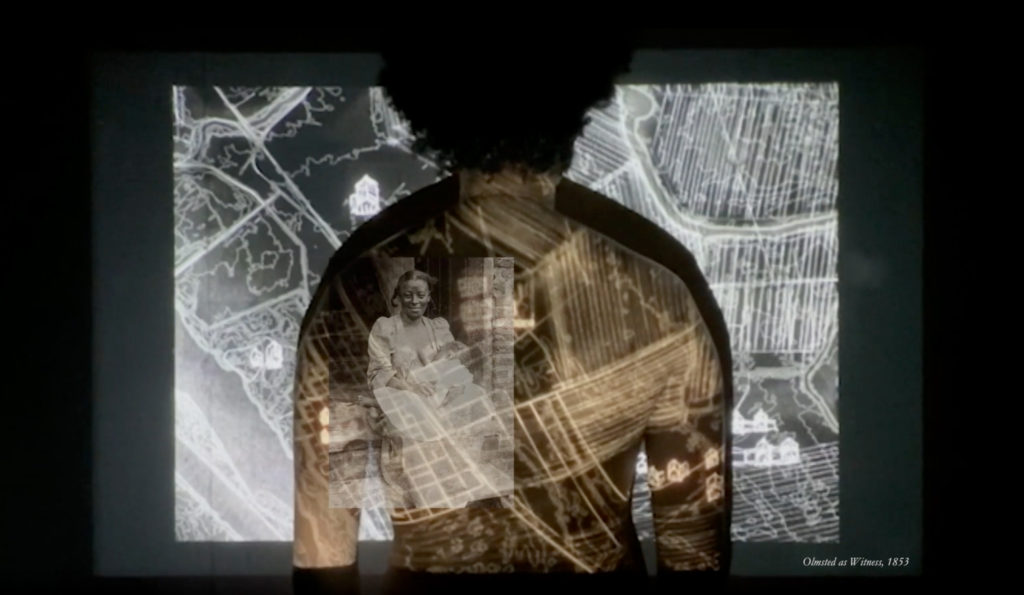

Video still from Aria Griffin and Kanchan Wali-Richardson’s “From Womb to Womb”

L. Blount (MLA ’17) is changing how we envision the natural landscape—and how people of color are depicted within it

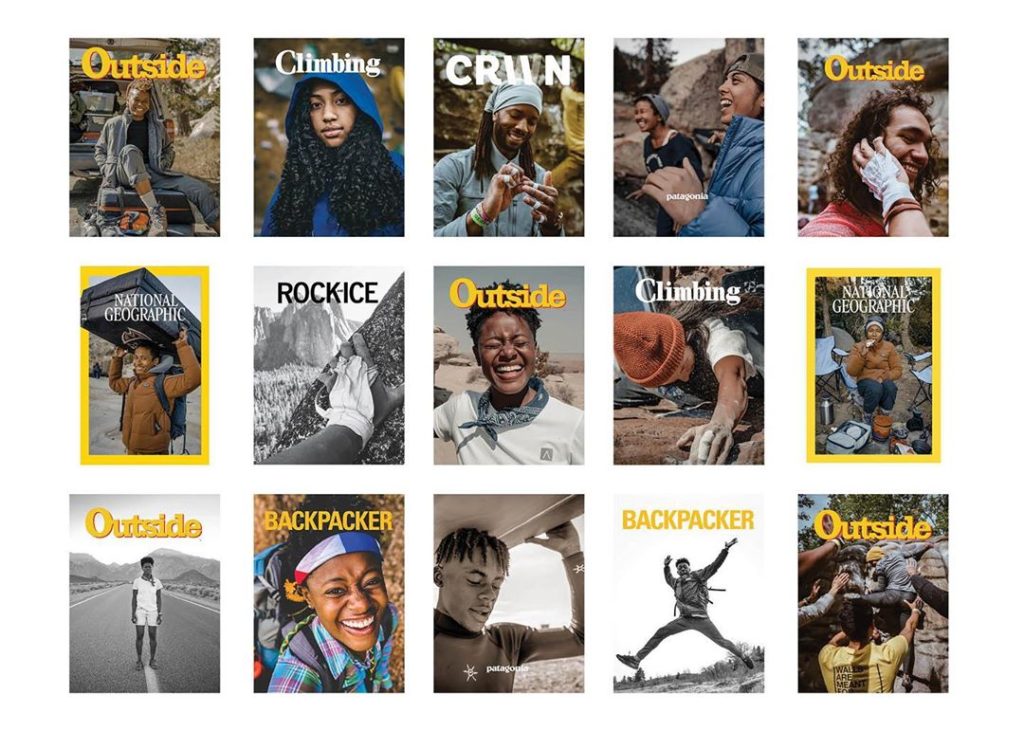

Although she graduated from the Harvard Graduate School of Design Master in Landscape Architecture program in 2017, Lanisha “L.” Blount would be hard-pressed to call herself a designer—the term “designer” feels too limiting to describe the range of her professional interests and activities. When she’s not hanging onto the edge of a boulder by her fingertips, or composing photo essays of her friends on their climbing adventures all over California with brands like The North Face and Arc’teryx, she’s working as an innovation consultant, partnering with Fortune 100 companies to help shape the future of their industries. “My path from the GSD has been very non-traditional,” Blount acknowledges. “But who says you have to be a traditionalist to change things? There’s more than one way to effect change in the environment, and I wanted to think much bigger.” Lately, Blount has trained her focus on changing how we envision the natural landscape—and specifically, how people of color are depicted within it. As outrage over George Floyd’s killing sparked conversations about systemic racism across the country, and the coronavirus pandemic precipitated a spike in traffic to national parks, Blount was compelled to bring the outdoor and adventure industry into the dialogue. “I looked up these [adventure] magazines to see the last time they had a person of color on the cover and it was often not even in the last two years,” she says.In response, she designed and posted to Instagram a series of speculative covers for major outdoor publications, each featuring her powerful portraits of climbers of color of all genders. With these visual provocations learned from consulting, Blount asked fellow adventurers to “imagine if [they] didn’t have to imagine.” Blount’s project also explicitly called upon leading outdoor brands to step up their efforts to build a more diverse and inclusive industry. “June was such a harrowing month,” Blount recalls. “Doing this storytelling was all about illuminating joy outside and rethinking how I can keep elevating people who should be on covers.”

Covers from Blount’s viral social media series. Image courtesy of her Instagram (@urbanclimbr).

Blount (MLA ’17) during her time as a student at the GSD. Image courtesy of her Instagram (@urbanclimbr).